ortho- baca

-

Upload

achmad-farid-dentist -

Category

Documents

-

view

85 -

download

5

Transcript of ortho- baca

tandläkartidningen årg 91 nr 3 1999

P R I M A R Y A N D M I X E D D E N T I T I O N O R T H O D O N T I C SV E T E N S K A P

Orthodontics in 12-year-oldsEvaluation of treatment in the primary andmixed dentition in general dental practice

Lena Andrup, Kerstin Ekblom and Bengt Mohlin

AuthorsLena Andrup,Chief DentalOfficer, Specia-list OrthodonticClinic, Mölndal,BohuslänCounty;Kerstin Ekblom,Chief DentalOfficer, ÅbyPublic DentalService Clinic,Mölndal,BohuslänCounty;Bengt Mohlin,AssociateProfessor,Department ofOrthodontics,Institute ofOdontology,GöteborgUniversity,Göteborg,Sweden.

Key wordsMalocclusion;orthodontics;interceptive;methods.

Accepted forpublication 10December 1998

O rthodontic treatment in youngchildren is usually interceptive orprophylactic. The phrase “inter-ceptive orthodontic treatment” is

open to interpretation, and the borderline betweenprophylactic and definitive treatment is notsharply drawn. In this study the phrase “inter-ceptive orthodontic treatment” implies treatmentprovided when an individual demonstrates a cleardeviation from optimal occlusal development –whether due to environmental or other causes –to encourage a patient to resume optimal occlusaldevelopment. The treatment has limited aimsand is of short duration. Interceptive treatmentusually involves early diagnosis. The treatment isusually, but not always, uncomplicated.

There are occasions when early definitivetreatment is appropriate to avoid damage to thedentition or to avoid more complicated andexpensive treatment when the patient is older.Relevant examples are the early correction ofincreased overjets to avoid traumatic injuries toanterior teeth [1] and the occlusal management ofpatients with hypodontia.

Definitive treatment for dental crowding onaesthetic grounds should almost always be post-poned until the individuals are mature enough tomake their own decisions concerning treatment [2,3]. The results of classical serial extractions havenot lived up to expectations when compared withthe results of treatment carried out in older patients[4].

According to the orthodontic literature, func-tional anterior and lateral crossbites, large overjets,and abnormal dental eruption patterns may allbenefit from early treatment.

Functional lateral crossbites, also known aslateral forced bites, have been associated with therisk of asymmetric craniofacial development with

Ortodontisk behandling i primärabettet och växelbettet bör inriktasmot funktionella avvikelser som kanstöra en optimal bettutveckling, så-som tvångsbett, och mot avvikandeeruption av tänder. Tidig planeringav aplasifall kan minska behov avsenare komplicerade insatser. Tidigreduktion av stora överbett somtraumaprevention tycks också varavälmotiverad. Behandling med över-vägande estetisk motivation bör inteutföras förrän patienten är mogenatt själv ta beslut om åtgärd, i deflesta fall efter växelbettsperioden.

Samtliga 12-åringar som tillhördeen folktandvårdskliniks upptagnings-område kallades för klinisk under-sökning och intervju. I flertalet fallöverensstämde klinikens behandlings-prioriteringar med de ovan nämnda.Dock hade endast omkring 1/3 avstora överbett reducerats genombehandling. Nästan lika många hadeinte noterats eller åtgärdats. Trau-mafrekvensen var nästan 3 gångerstörre redan vid överbett omkring4,5 mm jämfört med mindre över-bett. Resultaten understryker beho-vet av effektiv reduktion av över-bett redan i tidigt växelbett.

tandläkartidningen årg 91 nr 3 1999

A N D R U P E T A L .

various degrees of severity. Increased electricalactivity in the temporal muscle on the crossbiteside and a displacement towards that side havebeen recorded [5–7]. Lateral crossbites may alsopresent an obstacle to the increasing intercaninewidth, which would be expected as the maxillarycanines complete eruption. Consequently, spaceconditions within the occlusion become un-favourable. At present, it is not easy to predict howimportant the effects of functional crossbites are,but on the other hand, limited treatment tocorrect functional crossbites usually seems to bejustifiable.

Functional anterior crossbites, also known asfunctional anterior displacements, may preventproclination of maxillary incisors taking placeduring eruption. This may lead to a reduction in theforwards development of the anterior segment of

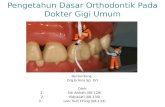

Figure 1a,b. A 12-year-old boy with an 8-mm overjet and incompe-tent lip posture. He was treated with a removable appliance in themaxilla to retract the maxillary incisors 2–3 years ago. Compositerestorations on 11 and 21 are due to crown fractures.

the maxilla. Proclination of the mandibular incisorsegments may follow as a consequence, but this hasyet to be clearly documented. Early orthodontictreatment using reversed headgear may have anorthopaedic effect on the maxilla in addition toencouraging the correction of the functional dis-placement [8, 9]. Creation of a normal inter-maxillary compensation may encourage a betterocclusal development. It may be difficult to predictthe results of treatment for the individual patient,but treatment of functional anterior crossbite iseasy to perform and may reduce the need for morecomplex treatment in a considerable number ofpatients [10]. In addition, there may be less risk ofthe development of temporomandibular disorders,TMD, in later years [11].

Patients with large overjets have an increasedrisk of traumatic injuries to the maxillary incisorteeth [1]. Most of these accidents occur before10–11 years of age and the prevalence of injuries topermanent teeth has been reported to be about20% [1, 12]. Almost half of the injured permanentteeth required treatment according to Forsbergand Tedestam [12]. The teeth most often damagedare 11 and 21 [1]. Thus, early orthodontic cor-rection of large overjets is a valuable preventiveinitiative. Two other benefits of the early re-duction of large overjet are known. The establish-ment of normal lip posture may influence occlusaldevelopment in a positive way and improve thevertical tooth support. Increased overjet has beenassociated with increased plaque accumulationand gingival inflammation [13]. Although a poorperiodontal condition is not, on its own, a majorindication for treatment, the improvement ingingival conditions remains an important addi-tional benefit of overjet reduction. Orthodontictreatment in the early mixed dentition can usuallybe achieved using simple appliances such as anactivator or headgear.

The normal tooth eruption pattern may besignificantly affected by supernumerary and con-genitally missing teeth and, in addition, by theectopic eruption of permanent teeth such as themaxillary canines. Early diagnosis and treatmentplanning for certain patients with congenitallymissing maxillary lateral incisors to encouragespace closure may reduce the need for com-plicated rehabilitation. This simple approach totreatment is usually well accepted by patients. Theectopic eruption of maxillary canines should bedetected at about 10 years of age. Canines can beencouraged to move towards a more normal pathof eruption by providing space and removing theprimary canines. Hence, early intervention maysave resources and reduce the need for advancedorthodontic treatment [14].

a

b

tandläkartidningen årg 91 nr 3 1999

P R I M A R Y A N D M I X E D D E N T I T I O N O R T H O D O N T I C S

A few studies have evaluated the quality ofmixed dentition treatment in general dentalpractice. Bäckström [15] and Follin et al. [16]reported on prevalent failures with activatortreatment in general practice. In addition, Follinand Milleding [17] reported many complicationsduring arch expansion with the quadhelixappliance.

The aim of this study was to evaluate theeffectiveness of diagnosis and treatment duringthe primary and mixed dentition period in ageneral practice. In a later report, the functionalstatus, the future treatment needs, and the desirefor treatment in 12-year-old children will beevaluated. The present study analysed thefollowing questions:● Had important malocclusions been diagnosed

and treated? For the purposes of this study,these were:– Large overjet– Functional lateral crossbite– Functional anterior crossbite– Ectopic eruption of maxillary canines– Congenitally missing teeth– Hypodontia and abnormalities of normal eruption

● Was the technical quality of treatment accept-able?

● To what extent had the aims of treatment beenrealised?

● To what extent had other malocclusions re-ceived treatment?

Material and methodsSubjectsAll 12-year-old children listed at the Åby PublicDental Service Clinic, Mölndal, Sweden, wereinvited for dental examination; 283 children wereasked to participate. Six had moved from the areaor were on the lists of other clinics. Fourteen didnot wish to participate or repeatedly failed toattend. The study group thus consisted of 263individuals, which is 93% of the 12-year-oldchildren listed in the clinic at the time ofexamination. The sex distribution was even, with130 boys and 133 girls.

All individuals were subjected to the followingexaminations: clinical examination of occlusalfunction and morphology, intra-oral clinicalphotos from the frontal and lateral aspects, andextra-oral three-quarter profile views with the lipsat rest. The children were interviewed and askedabout previous experience of treatment, previousorthodontic treatment, and their feelings aboutwhether orthodontic treatment would be ofbenefit to them. Patient records were analysed.

Clinical examinationsAngle´s classification of the sagittal occlusion wasrecorded with the lip posture at rest; overjet,overbite, and any gingival contact by the mandi-bular incisors were also recorded. Lateral cross-bites involving at least two teeth and anteriorcrossbites involving at least three teeth, ectopicallyerupting teeth, congenitally missing teeth, andsupernumerary teeth were recorded. The presenceof ectopic eruption or hypodontia was confirmedby available X-rays. The presence of frontalirregularities and an overall evaluation of theaesthetic impression will be presented and dis-cussed in a separate paper.

Lateral and anterior functional displacementwas recorded from the retruded contact position,RP. The result of the complete functional exa-

Figure 2. Tooth 23 was diagnosed as erupting ectopically in a mesiallyinclined position. Tooth 63 was recently extracted to encouragenormal canine eruption.

Figure 3. One of the (few) patients already referred for specialisttreatment on psychosocial indications.

tandläkartidningen årg 91 nr 3 1999

A N D R U P E T A L .

mination will also be presented and discussed in alater paper.

InterviewsA structured interview was performed by one ofthe examiners (BM). The interview includedquestions on the children´s worries about visits tothe dentist, their previous dental experience, theirthoughts about the appearance of their teeth, theirwishes for improvements in their dental status(stated in ranking order, including shape, colour,oral function, and finally, general dental health),their wishes for changes in the position of theirteeth, their previous experience of orthodontictreatment, and whether they suffered from head-ache or experienced temporomandibular joint(TMJ) sounds, and/or locking/luxation of the TMJ.

Dental recordsThe following items were recorded: time andreason for consulting a specialist; orthodontic

treatment including the reason for treatment, thetype of appliance used, the number of check-ups,appliance activation and complications duringtreatment, co-operation, and the treatment resultaccording to the clinic records; and traumaticdental injuries including the nature of the injury,when it occurred, and what was done afterwards.Some details of general dental treatment were alsonoted: poor oral hygiene, high caries experience,extractions, and endodontic treatment. Infor-mation on the duration of individual courses ofdental treatment was extracted from the clinic´scomputer records.

AssociationsThe possible increase in the risk of traumaticdental injuries was calculated as relative risk (admodum Tayler) with a 95% confidence interval.Figures above 1 imply an increased risk. The chi-squared test was used to establish significantdifferences in the influence of an overjet on theprevalence of traumatic dental injuries.

ResultsSagittal occlusionOf the 263 children, 202 (77%) had an Angle´sclass I, 60 (23%) an Angle´s class II, and only onechild an Angle´s class III occlusion.

Thirty-four children (13%) had an overjet of≥6 mm, 25 of these children also had incompetentlips. Ten (29%) of these 34 children with recordedlarge overjets ≥6.0 mm, had received treatment toreduce their overjets (according to the clinicrecords) (Table 1). Another nine children hadreceived treatment and achieved an overjetreduction to <6 mm; six of these children still hadan overjet of ≥4.5 mm.

Another 12 of the 34 overjet children (35%)had seen an orthodontist, but no treatment hadyet begun. The remaining 12 subjects withincreased overjet (35%) had not receivedtreatment or consultation according to the clinicrecords and the results of the interview with thechildren.

The prevalence of traumatic injuries affectingboth deciduous and permanent maxillary incisorswas analysed with respect to overjet. Forty-threechildren were initially and/or currently defined ashaving large overjets. Twenty-two (51%) of thesechildren compared to 67 (31%) of the 220 whohad no previous or present significant overjet hadsuffered incisor trauma. Ten (29%) of the 34children with an overjet ≥6.0 mm at the time ofexamination had a history of trauma affectingpermanent incisors compared to 32 (14%) of the229 who had no significant overjet.

Table 2. Prevalence (n; %) of traumatic injuries to permanentincisor teeth in 263 12-year-old children with and withoutlarge overjets ≥6.0 or ≥4.5 mm.

Overjet Injuries No injuries Total(mm) (n) (%) (n) (%) (n) (%)

>6.0* 10 29.0 24 71.0 34 100<6.0* 32 14.0 197 86.0 229 100

>4.5** 16 32.0 34 68.0 50 100<4.5** 26 12.0 187 88.0 213 100

*p=0.021; RR=2.1 (risk for injuries 110%); 95% confidence interval: (1.14–3.88)**p=0.0006; RR=2.62 (risk for injuries 162%); 95% confidence interval: (1.53–4.50).

Table 1. Prevalence (n; %) of diagnosed and treated overjet in263 12-year-old children. Figures are presented in overjets≥6.0 or ≥4.5 mm

Present Diagnosed subjects Treated subjectsoverjet (mm) (n) (%) (n) (%)

>6.0 34 12.9 10 3.8<6.0 229 87.1 9 3.4

>4.5 50 19.0 16 6.1<4.5 213 81.0 3 1.1

Total 263 100.0 19 7.2

tandläkartidningen årg 91 nr 3 1999

P R I M A R Y A N D M I X E D D E N T I T I O N O R T H O D O N T I C S

When large overjet was defined as an overjet≥4.5 mm, 50 children were defined as having largeoverjets; 16 (32%) of these had suffered traumaaffecting permanent incisors. Of the 213 childrenexcluded from the definition of increased overjet(≥4.5 mm), 26 (12%) still had a history of traumaaffecting permanent incisors. Associations be-tween traumatic injuries and overjet are presentedin Table 2.

Functional lateral crossbiteOnly one patient had a forced lateral crossbite.Nine subjects had a lateral crossbite without anyfunctional deviation. Twenty-nine children hadreceived treatment for lateral crossbites; 14 ofthese had received treatment to eliminate thefunctional shift, but there was no informationabout possible functional deviation for the other15 children.

Functional anterior crossbiteNo children had functional anterior crossbite.According to the clinic records, two childrenreceived treatment. Minor functional displace-ment from RP to IP was found in seven patients.

Ectopic eruption of caninesEighteen children had had a diagnosis of, andsometimes treatment for, ectopic canine eruption.Three children had had deciduous canines ex-tracted. Nine children had one or two un-diagnosed maxillary canines at the time of thesurvey. No reference had been made to theirunerupted canines nor had any X-rays been takenduring the previous 2 years.

Congenitally missing teethTwo children had multiple congenitally missingteeth; both had been referred to a specialist clinic.Two children with missing maxillary lateral in-cisors had been identified. One with a congeni-tally missing mandibular incisor appeared not tohave been diagnosed. Eleven children were foundto have missing second premolars, all in all 9 in themaxilla and 15 in the mandible. Three childrenhad only one second premolar missing; five hadtwo second premolars missing. Three otherchildren had at least three second premolarsmissing. The congenitally missing teeth had beenidentified in the clinic records of 9 of the 11children. The remaining two children had re-ceived orthodontic treatment (with either an ac-tivator or a quadhelix appliance), but hypodontiahad not been diagnosed and the treatment had notbeen planned to address this problem.

ExtractionsFourteen children had undergone extraction ofpermanent teeth. In one child this was due toendodontic reasons; in two children it was due toimpaction or ectopic eruption. In five childrensupernumerary teeth had been removed (twobeing a mesiodens). In two children the extrac-tions were compensatory due to congenitallymissing teeth. In six children teeth had beenextracted to relieve crowding.

A few patients had combinations of reasons forextraction, and these usually involved crowdingand supernumerary or congenitally missing teeth.Extractions of primary teeth had been carried outin four children who had congenitally missing orsupernumerary teeth.

Early appliance treatmentActivators, extra-oral traction with headgear,removable appliances, and quadhelices had beenprescribed for 13 children each. Three childrenhad been treated with dental cribs, four withlingual arches, and two with sectional arches.Twelve children had been treated with more thanone appliance. The indications for treatmentincluded crowding (six children, four with ex-tractions and appliances), spacing (four children),deep bite (two children), and sucking habits (fourchildren). Combinations such as increased overjetand deep bite had often been encountered.

Of the 49 children who had answered questionsabout difficulties with orthodontic appliances, 25(51%) reported no significant problems whenwearing the appliances, 14 (29%) had ex-perienced moderately severe problems, and 10(20%) were in no doubt that they had metdifficulties in managing the appliance. A clearevaluation of the results of treatment was oftenabsent in the patient´s records.

DiscussionMost orthodontic treatment carried out in the 12-year-old children in this study was provided tocorrect forced occlusion, to reduce large overjet(associated with an increased risk of traumaticinjuries), and to deal with various problems oftooth eruption; all these therapies are well moti-vated for early treatment as outlined in theintroduction. The proportion of subjects who hadbeen diagnosed and treated successfully variedconsiderably between these different mal-occlusions.

In this study, large overjets accounted foralmost 13% of the children. This is very similar tothe prevalence of increased overjet found in 10-year-old children in Göteborg 25 years earlier

tandläkartidningen årg 91 nr 3 1999

A N D R U P E T A L .

when the resources were more modest [18], and italso agrees with early data from a number of otherScandinavian studies [19]. Almost one third of thechildren with increased overjet did not have thediagnosis in their dental records. Another thirdhad seen an orthodontist but had not receivedtreatment promptly. The final third had receivedtreatment and their overjets had been reduced toless than 6.0 mm but the overjet remained greaterthan 4.5 mm in several children.

Orthodontic intervention and successful treat-ment for this vulnerable group of patients has beenmodest, which is in agreement with conclusionsdrawn by Bäckström [15] and Follin et al. [16].Our study did not identify a single principal causebut some possible reasons are failure in clinicalobservation and diagnosis, e.g. failure to identifymouth breathing, or failure in clinical technique.The patients themselves may not have been wellmotivated. Indeed, most of the treatmentregimens employed were demanding and requiredgood co-operation if they were to succeed. Almostone-half of the vulnerable children had not re-ceived diagnosis or treatment, which implies thatmany dentists do not feel that early reduction ofoverjet is a priority.

In 1979 Järvinen [1] reported the association oflarge overjet and traumatic injuries to themaxillary incisors and our figures confirm hisobservation. The prevalence of injury to per-manent maxillary incisors in children with largeoverjet was twice that of their peers; even anoverjet of 4.5 mm carries an increased risk ofdental injury. Our figures are extracted from theclinic records, and it is reasonable to assume thatmost severe injuries had been reported. Never-theless, there may be some underreporting of thetrue situation. Even with this proviso our figuresunderline once again the benefit of early diagnosisand treatment.

Diagnosis and treatment of lateral and anteriorfunctional crossbite had been carried out moreeffectively than when the issue was reviewed byFollin and Milleding [17]. Almost all of thesemalocclusions had been successfully identifiedand treated. The majority of patients were treatedwith appliances which did not require much co-operation, but even here, some difficulties inmanagement had to be overcome. The distinctionbetween functional and non-functional lateralcrossbites was not always clear in the patient´srecords.

The majority of congenitally missing andsupernumerary teeth had been identified anddealt with promptly. Only one patient with amissing mandibular incisor had been overlooked.Two children with absent second premolars might

have been overlooked: clinic records were notclear. All patients with ectopically erupting molarshad been treated. Identification of ectopic canineeruption ought to have been made by 12 years[14], but there had been a failure of diagnosis forseveral patients.

Most of the extractions of permanent teeth hadbeen undertaken to deal with the problems oferuption or of supernumerary or congenitallymissing teeth. Only six patients had had per-manent teeth extracted to relieve crowding. Thisagrees with a circumspect attitude to the earlytreatment of malocclusions where the indicationfor treatment was primarily aesthetic andpsychosocial rather than functional [2, 3].

The appliances used most frequently were thesame as those previously reported by Swedishorthodontists [20]. Specifically, they were acti-vators, headgear and removable appliances, quad-helices followed by other types of lingual arches,and finally, a small number of sectional arches.Mohlin and Persson [20] also found that dentalstudents and young general practitioners had notbeen well trained in the techniques of orthodontictreatment. Over one-third of the orthodontistsapproached for their comments agreed that theorthodontic skills of general practitioners wereinadequate. The modest results of treatment forincreased overjet identified in our study underlineagain the need for improvements in under-graduate training and continuing professionaleducation for general practitioners.

The demand for treatment in the 12-year-oldsand estimates of the future need for orthodontictreatment on functional and psychosocial groundswill be analysed in a separate paper.

SummaryOrthodontics in 12-year-olds.Evaluation of treatment in the primary andmixed dentition in general dental practiceLena Andrup, Kerstin Ekblom, Bengt MohlinTandläkartidningen 1999; 91(3): 29–35

Based on the results of the present and previousstudies we suggest that the orthodontic treatmentpriorities during the primary and mixed dentitionperiods should be:● The elimination of anterior and lateral forced

bites which interfere with normal occlusal andcraniofacial development.

● The problems associated with the eruption ofteeth.

● The early management of patients who havecongenitally missing teeth.

tandläkartidningen årg 91 nr 3 1999

P R I M A R Y A N D M I X E D D E N T I T I O N O R T H O D O N T I C S

● The reduction of large overjets to reduce therisk of traumatic injuries to the permanentincisors.

All 12-year-old children registered at a generaldental practice were called for clinical examina-tion and interview. Only one patient was found tohave an untreated functional crossbite. Most pa-tients with problems of eruption and congenitallymissing teeth had been identified. Only about onethird of the patients with a large overjet had re-ceived successful interceptive treatment and asmany had not been identified. For patients with anoverjet of 4.5 mm and above, the prevalence oftraumatic injuries was increased almost 3 times.

This underlines the need for effective reductionof large overjets in the early mixed dentition.

References1. Järvinen S. Traumatic injuries to upper permanent inci-

sors related to age and incisal overjet. Acta OdontolScand 1979; 37: 335–8.

2. Shaw W C. Factors influencing the desire for ortho-dontic treatment. Eur J Orthod 1981; 3: 151–62.

3. Espeland L, Ivarsson K, Stenvik A, Album Alstad T.Perception of malocclusion in 11-year-old children: acomparison between personal and parental awareness.Eur J Orthod 1992; 14: 350–8.

4. Little RM, Riedel RA, Engst ED. Serial extraction of firstpremolars – postretention evaluation of stability andrelapse. Angle Orthod 1990; 60: 255–62.

5. Ingervall B, Thilander B. Activity of temporal and mas-seter muscles in children with a lateral forced bite.Angle Orthod 1975; 45: 249–58.

6. Hamerling K, Naeije C, Myrberg N. Mandibular func-tion in children with lateral forced bite. Eur J Orthod1991; 13: 35–42.

7. Pirttiniemi P. Associations of mandibulofacial asymme-tries with special reference to glenoid fossa remodel-ling. Thesis. Oulu: University of Oulu, 1992.

8. Baumrind S, Korn EL, Isacson RJ, West EE, Molthen R.

Quantitative analysisof the orthodontic and ortho-paedic effects of maxillary traction. Am J Orthod 1983;84: 384–98.

9. Mermigos J, Full CA, Andreasen G. Protraction of themaxillofacial complex. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Or-thop 1990; 98: 47–55.

10. Delaire J. Maxillary development revisited: relevanceto the orthopaedic treatment of Class III malocclu-sions. Eur J Orthod 1997; 19: 289–311.

11. Mohlin B. Need for orthodontic treatment with specialreference to mandibular dysfunction. Thesis. Göte-borg: Göteborg University,1982.

12. Forsberg C-M, Tedestam G. Traumatic injuries toteeth in Swedish children living in an urban area.Swed Dent J 1990; 14: 115–22.

13. Davies TM, Shaw WC, Addy M, Dummer PMH. Therelationship of anterior overjet to plaque and gingivitisin children. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988; 93:303–9.

14. Ericson S, Kurol J. Early treatment of palatally eruptingmaxillary canines by extraction of primary canines. EurJ Orthod 1988; 10: 283–95.

15. Bäckström A. Ortodontisk rådgivning i folktandvården.Tandläkartidningen 1985; 77: 219–22.

16. Follin M, Kahnberg KE, Sjöström O. Assessing the costsof activator treatment in general practice. Br J Orthod1993; 20: 235–40.

17. Follin M, Milleding A. Quad Helix treatment in generalpractice. Swed Dent J 1994; 18: 43–8.

18. Ingervall B, Seeman L, Thilander B. Frequency ofmalocclusion and need of orthodontic treatment in10-year-old children in Gothenburg. Svensk TandlTidskr 1972; 65: 7–21.

19. Helm S. Prevalence of malocclusion in relation to devel-opment of the dentition. An epidemiologic study ofDanish schoolchildren. Thesis. Acta Odontol Scand1970; 28: Suppl 58.

20. Mohlin B, Person M. Grundutbildningen i ortodonti vidett vägval. Tandläkartidningen 1995; 87: 451–7.

AddressBengt Mohlin, Institute of Odontology, GöteborgUniversity, Box 450, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden.