on a Grand Érard · Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) 14 3'39 Etude in b flat minor, op.8 no.11...

Transcript of on a Grand Érard · Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) 14 3'39 Etude in b flat minor, op.8 no.11...

-

Ranges of ÉrardKsenia Kouzmenko on a Grand Érard

HellerChopinSchumannDebussyDe FallaTchaikovskyRachmaninovScriabinCervantes

-

Stephen Heller (1813-1888) 1 2'24 Barcarolle, op.138 no.5 (1874)

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) 2 6'02 Nocturne in A flat Major, op.32 no.2 (1837) 3 7'16 Nocturne in B Major, op.62 no.1 (1846)

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) 4 6'47 Arabeske, op.18 (1838) 5 2'20 Intermezzo from “Faschingschwank aus Wien”, op.26 (1839)

Claude Debussy (1862-1918) 6 2'37 “…General Lavine - eccentric” (1912-13) 7 3'10 “…Bruyères” (1912-13) 8 3'30 “…La puerta del Vino” (1912-13)

Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) 9 2'42 “Homenaje a Debussy” (1920) 10 4'01 “Danza ritual del fuego” from “El amor brujo” (1915)

Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) 11 3'56 “May - White Nights” (1876) 12 4'18 Sentimental Waltz, op.51 no.6 (1881)

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) 13 3'04 Prelude in G Major, op.32 no.5 (1910)

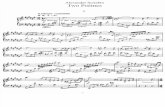

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) 14 3'39 Etude in b flat minor, op.8 no.11 (1895) 15 5'57 Poème “Vers la flamme”, op.72 (1914)

Ignacio Cervantes (1847-1905) 16 2'18 “Un recuerdo” (1875)

Ranges of ÉrardKsenia Kouzmenko Grand Érard

total time: 66'08

-

Ranges of Érard

Sébastien Érard (1752-1831) came to Paris as an eager boy of sixteen. In 1777 he built the first ever French piano.

He became a brilliant instrument maker (pianos, harps,

organs), and patented numerous improvements for the

piano which are still in use. It wasn’t long before he had

factories in both Paris and London: Érard became one

of the biggest brands of the 19th century. Famous Érard

owners included Haydn, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Heller,

Chopin, Liszt, Alkan, Franck, Fauré, Chausson, and Ravel.

This CD is recorded on a London Grand Érard from 1863.

Paris in the 19th century was a world-famous cultural

centre that attracted many artists and musicians. Stephen Heller (1813-1888) arrived in Paris in October of 1838, where he would quietly live and work for the rest of his life.

Schumann had sent him 25 Thaler as travel funds as well

as a copy of his “Kreisleriana”, which Heller was to pass on

to Chopin. Heller had great respect for Chopin as an artist,

and took up contact with him right away.

Heller was allergic for empty virtuosity. The CD begins

with his crystal clear little Barcarole, a “Song without Words” from opus 138, written in 1874. Heller was a great

fan of Érard.

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) came to Paris in 1831. He played on both Pleyel and Érard pianos, and during a stay

in London he had an Érard at his disposal. Chopin wrote

nocturnes throughout most of his life, as a sort of diary.

Almost all were written in three sections with a quiet,

lyrical, nocturnal beginning and end and a contrasting,

agitated middle section.

The Nocturne opus 32/2 in A flat Major was written in 1837. It begins with the long lines of a quiet melody

which occasionally has an elegiac feel. The middle section

becomes increasingly restless and dramatic, and when the

melody from the beginning returns with exactly the same

notes its character is changed completely from the first

section by the way it is played: intense and passionate.

The Nocturne opus 62/1 in B Major from 1846 is a marvellous example of Chopin’s mature style of writing.

Its structure is much more complex and forms a real

story, polyphonic, full of questioning intonations. Here the

middle section is not agitated but more grounded, with

a talking, almost arguing melody. At the reprise the main

theme returns floating in a bed of trills and ornaments.

Vienna was the other centre of musical activity in Europe.

Chopin and Heller had tried in vain to find a foothold

there, and Robert Schumann (1810-1856) also tried it for one winter. At the end of 1838, as his friend Stephen

Heller had just begun to find his way in Paris, Schumann

was in Vienna and composed, among others, the graceful

and transparent Arabeske opus 18. In March 1839 he began the “Faschingsschwank aus Wien” in Vienna. The passionate Intermezzo that is now a movement of that work was first published at the end of 1839 in Schumann’s

“Neue Zeitschrift für Musik” as one of a series of soon to

be released “Nachtstücke”. But at this point Schumann

had already been back in Leipzig for six months.

It seems that Claude Debussy (1862-1918) had a very personal, orchestral style of piano playing. He only played

occasionally in public, mostly as an accompanist of his

songs and much more rarely as a soloist. On 25 May 1910

he performed four of his preludes in the Salle Érard, and

another four on 29 March 1911. The critic Auguste Mangeot

wrote about the performance: “Is there a pianist who has

a more beautiful sound than Debussy on an Érard? I don’t

think so.”

Edward Lavine was a famous American vaudeville

comedian and juggler who also performed in Paris.

It seems that the director of the Marigny Theatre

Sébastien Érard Stephen Heller Frédéric Chopin Robert Schumann

-

approached Debussy to write the music for a show

developed around General Lavine. The show never took

place but the prelude “…General Lavine - eccentric” manages to convey a humorous atmosphere of jerky

movements and absurd humour very well. It is a highly

sophisticated satire.

“…Bruyères” (Heather) offers a calm pastoral scene with a touch of loneliness. Everything sounds calm, wide,

and undulating.

“…La puerta del Vino” was inspired by a postcard with an image of a gate of the Alhambra in Granada sent

to Debussy by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla.

Debussy wanted a Habanera character, and indicates:

with abrupt contrasts of extreme violence and passionate

softness. Debussy never visited Spain himself but

miraculously managed to find the colour of Spanish music

in this piece.

The influence Debussy had on other composers was

enormous. Many came to Paris specifically to meet him,

and to learn from him. This was the case for the young

Spanish composer Manuel de Falla (1876-1946). Debussy listened to his work and found it very good. They ended

up becoming friends, and after Debussy’s death de Falla

wanted to write a musical memorial. It became the guitar

piece “Homenaje”, first published in a special issue of the “Revue musicale” entitled “Tombeau de Claude Debussy”.

At the end of this darkly hypnotic piece de Falla quotes

a motif from “Soirée dans Grénade” by Debussy. The

famous “Danza ritual del fuego” is part of the ballet “El amor brujo”, inspired by the beautiful Gypsy dancer

Pastora Imperio. It is not about the “power” of love but

rather magic, wondrous rituals, and witchcraft. De Falla

transcribed both pieces for piano himself.

In the 19th century there were many strong cultural ties

between France and Russia. French was the language of

the Russian salons, and rich Russian families employed

French teachers for their children. Many French musicians

and artists also travelled to Russia. For example, at one

point Nadezhda von Meck had Debussy as a house

musician and piano teacher for her children. But she

played a very important role in the life of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893). In addition to supporting him financially she was also a dear friend. His “May - White Nights” from the piano cycle “The Seasons” is a beautiful representation of a clear northern summer night, during

which it never really gets dark. The “Sentimental Waltz” sounds like the melancholy tale of a past experience.

These pieces would have certainly been heard in both

Russian and French salons.

In May 1906 Diaghilev began his “Russian Seasons”

in Paris and it became a milestone for Russian music.

Rimsky-Korsakov, Glazunov, Scriabin, Shaliapin, and many

others were invited. Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) participated in these concerts as a composer, conductor,

and pianist. His Prelude in G Major was written in the

summer of 1910 in Ivanovka, on his family’s estate. It is

actually the last sunny, lyrical piece that Rachmaninov

ever wrote. You hear the wide air, the summer light, and

the lark singing above the endless fields.

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915), a fellow student and friend of Rachmaninov’s from the Moscow Conservatory,

performed several times at the Salon Érard in Paris. One

of the pieces he played there is the Etude in b flat minor op. 8/11.

The Poème “Vers la flamme” is one of Scriabin’s last works. He was feverishly engaged in that period with all

sorts of mystical ideas about the end of the world and the

salvation of mankind. The piece has many layers in timbre,

register, and dynamics. It is an inevitable but exciting

process from the first bewitching moments to the flaring

up of a cosmic fire.

Cuban composer Ignacio Cervantes (1847-1905) studied in Paris from 1866 to 1870. He had lessons from Alkan

and also Marmontel, who later became one of Debussy’s

teachers. Cervantes was very successful in Paris as a

pianist and vocal accompanist and was highly appreciated

by artists such as Liszt, Gounod, and Rossini. “Un recuerdo”, written in 1875, is one of his 41 Danzas for piano - short character pieces in dance form.

Claude Debussy Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Sergei Rachmaninov Alexander Scriabin Ignacio CervantesManuel de Falla

-

Ksenia Kouzmenko is renowned internationally for her

sensitive and technically accomplished piano playing,

and is a much sought after partner in chamber music.

Ksenia was born in Minsk, Belarus, to a family of

pianists. She studied with Vladimir Zaretsky and Grigory

Scherschewsky, the former teacher of her father, at the

National Music College in Minsk. At the age of twelve

Ksenia made her solo debut with orchestra. Over the

next few years she performed the piano concertos of

Beethoven and Rachmaninov. She graduated cum laude,

with a Gold Medal. Ksenia continued her piano studies at

the National Music Academy with Igor Olovnikov, where

she received her Master degree cum laude as a soloist,

teacher, and in vocal accompaniment and chamber music.

She pursued her postgraduate studies with Naum Grubert

at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague, with financial

support of the Yuri Egorov Foundation.

She has taken part in many masterclasses with

outstanding musicians such as Abbey Simon, György

Sándor, Earl Wild, György Kurtág, and Ivan Moravec,

and attended courses in Bach-interpretation with Walter

Blankenheim. In the summer of 1997 she followed an

intensive chamber music program at Tanglewood in

the USA.

Ksenia has received prizes for accompaniment at

numerous international competitions. As a soloist she

won the 2nd prize at the Tromp Competition in Eindhoven,

where she also received the Audience Prize, and the 3rd

prize at the Rencontres Musicales de Gaillard, France.

She has performed with the National Symphony

Orchestra of Belarus, the Brabants Orkest, the

Collegium Instrumentale Brugense, and the Nederlands

Blazersensemble. She was a soloist in the Kurtág-project

of the Royal Conservatory conducted by Reinbert de

Leeuw, and on recommendation of György Kurtág himself

played his “...quasi una fantasia...” with the Orchestra della

Svizzerra Italiana conducted by Olivier Cuendet, at the

Lugano Festival. She recorded concerts for the National

Broadcast Corporation of Belarus, Radiotelevisione

Svizzerra, Dutch television, and Dutch and Belgian

national radio channels (Radio 4 and Brava).

Ksenia has been performing in Germany (Beethoven

Festival in Bonn), England, Greece, Switzerland, Belgium

(Festival van Vlaanderen), Italy, Slovenia (Tartini Festival),

Spain (Festival “Semana de Musica Caja Astur”), Russia

(Hermitage, St. Petersburg), and all over the Netherlands.

She has played chamber music in almost every

combination possible, and has built up an enormously

wide-ranging repertoire from Bach to Kurtág. Ksenia is

constantly searching for new compositions and is fond of

making unusual, inspiring programs. Among her long-time

partners are wonderful musicians such as the violinist

Lisa Jacobs, cellist Lucie Štĕpánová, and clarinettist

André Kerver.

Since 1999 Ksenia has been teaching at the Royal

Conservatory of The Hague.

In 2013 violinist Lisa Jacobs and Ksenia Kouzmenko

released the CD “Poème” on Challenge Records, featuring

compositions of Franck and Ysaÿe. The CD “Whispering

Leaves” with the cellist Lucie Štĕpánová was released in

2018 on Cobra Records, with works of Janáček, Páleníček

and Martinů. Both recordings were highly praised by the

international music press.

“Ksenia Kouzmenko is a convincing performer, whose elegant gestures are always subordinated to the music. She sweeps the listener along on her musical explorations.” — Tromp Competition

Ksenia Kouzmenko on the Grand Érardduring the recording session.

Ksenia Kouzmenko

-

One of the most fascinating things that you experience

as a musician is that you keep learning and discovering

throughout your whole life.

In 2017 I was asked to give a solo concert on an Érard

grand piano from 1863. I was hesitant, as I had never

played on such an instrument. But my curiosity about

a grand piano on which so much music of the 19th

century was composed and played was too great. It was

very interesting to discover so many new timbres and

possibilities. After the concert, Zefir Records suggested

recording a CD on this instrument.

I thought it would be fun to put together a labyrinthine

programme, in which you could always take a different

path after each piece and create new stories. This CD is

just one example, and everything takes place within the

ranges of Érard.

What is so special about this instrument? In contrast

to the modern, overstrung grand piano where the bass

strings lie diagonally across the other strings - which

makes the sounds mix together more - the strings of an

Érard grand run parallel to each other. And to the wood

grain of the soundboard: the dark stripes are the winter

wood, the light lines are the summer. The winter provides

the stiffness of the wood, the summer the passage of

the sound. Through these parallel strings you hear all the

voices very clearly, so you can play with more refinement

and nuance. I think it has also influenced the way I now

play on a modern grand piano.

It also works as a fascinating time machine: the Érard

grand piano was hugely popular and beloved in the 19th

century, and we can therefore better imagine how music

must have sounded like in that period.

This beautiful instrument, from the estate of Leen de

Broekert, is on loan from Liesbeth Binkhorst to the

Zeeland Concert Hall in Middelburg.

Recording on this grand piano was also quite an

adventure. Sometimes we had to find creative solutions to

deal with the 150+ year old mechanics. Piano tuner Joost

van Hartevelt even had to make a new bass string during

the recording sessions. But it was a real joy to discover the

radiant and overwhelming warm soul of this instrument.

— Ksenia Kouzmenko

“..Perhaps Heaven will do me the favour to be able to retire in some village close to the sea: there I would like to dress as a peasant, and possess nothing else but an Érard piano and a few books. Then I would be happy, and compose as I see it, and I would laugh about everything else..”— Stephen Heller, 23 July 1844, in a letter to Jenny Montgolfier.

-

Recorded at Zeeuwse Concertzaal, September 1 & 2, 2017

Mixed, edited by Jakko van der Heijden, Concertstudio (NL)

Mastered: Walter Calbo

Piano: Érard Concert Grand, 2.48m, London 1863

Piano technique: Joost van Hartevelt, De Hamernoot, Middelburg

Text: Ksenia Kouzmenko, Servaas Jansen

Translation: Katya Woloshyn

Photography cover: Ksenia Kouzmenko

Photography: Cornelia Unger, Jakko van der Heijden

Special thanks: Liesbeth Binkhorst, Servaas Jansen,

Villa Dorothy B&B Middelburg, Fransje Frohn & Tonnie Hugens

www.kseniakouzmenko.jouwweb.nl

www.zefi rrecords.nl