Occupational Health & Safety Magazine - Alberta · 4 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH & SAFETY MAGAZINE ¥...

Transcript of Occupational Health & Safety Magazine - Alberta · 4 OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH & SAFETY MAGAZINE ¥...

M A G A Z I N E

O C C U P A T I O N A L

V O L U M E 2 3 • N U M B E R 3 • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0

ChemicalConfusion

The InvisibleInjury

on the LooseHydrocarbons

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 02

A s an owner of an electrical contracting company, I havealways been concerned about workplace injuries. The

construction industry has an aging workforce, the work isphysically demanding and tasks are often very repetitive.Consistent procedures, safe work practices and personalprotective equipment help, but they don’t always prevent therepetitive strain injuries that are so common in our work . . .and elsewhere. Over the last ten years, strains have consis-tently accounted for over 40 per cent of the costs incurred by WCB.

Another challenge we face inconstruction is our mobile workforce.For the most part, work is notperformed at specific workstations, so ergonomic redesign of places where people work is not always an option.

In construction, short-termemployment presents another safetychallenge. Although some workers staywith one company for many years, asignificant number may work for acompany for only a few weeks. Still,the duration of employment shouldnot be a factor in the efforts we maketo prevent injuries. Employers aredoing the right thing in providingemployees with safety knowledge theycan use on the work site, at home oras a resource they take with them to a new job.

Stretching for safetyIn 1998, my company, Chemco Electrical Contractors Ltd.,worked with other partners at the Dow Chemical site to setup a pilot program designed to reduce all injuries, includingstrains. A survey of employees on the site indicated that theirconcerns about reducing injuries were the same as those ofmanagement. The introduction of a stretching program wasagreed upon.

Within a few months of launching the pilot program,and prior to being able to evaluate the results, we introducedthe pilot program to another site, AT Plastics, as they wereexperiencing a large number of strains. Most strainsoccurred while workers were pulling electrical cables. Thisrepetitive task can be very physically demanding because ofthe size and weight of the material being installed and theposition of the workers’ bodies while performing the task.

The Dow Chemical site recorded a 75 per cent reductionin strains, while the AT Plastics site reported a 50 per centreduction. At the AT Plastics site, the cable crews alonereported a 100 per cent reduction. In this pilot project,which involved approximately 400 Chemco employees, wenot only saw a definite decrease in strains reported but alsohad very positive feedback from employees.

In addition to stretching activities, the programeducated employees about incorporating stretches into theperformance of a task. This is beneficial for tasks that

require stationary positioning for longerperiods of time, as well as for tasks thatare repetitive. In both cases, workerstake short breaks while performingtheir tasks and stretch the muscles theyare working with.

Our efforts did not go unnoticed by our peers in the industry. Chemcoreceived the Syncrude ContractorRecognition Award for EnvironmentHealth and Safety for the mostinnovative environmental health andsafety idea implemented. And we wereselected as one of the three finalists forthe Workers’ Compensation Board 2000Worksafe Award of Distinction. Thesetributes have acknowledged ouremployees’ commitment to creating a safer work culture, not only forthemselves but for their fellow

workers, now and in the future.I have concluded that similar programs are needed on

all our job sites. The stretching program has had definiteshort-term benefits in reducing the number and severity ofinjuries. However, the potential for long-term benefits isimmense as well. Many musculoskeletal injuries are theresult of years of repeated activities that place stress ondifferent parts of the body. One of our more experiencedworkers put it well. “Where was this program 20 years agowhen I started in the trade?” he asked.

I see employees as the most valuable resource an organization has. We must do what we can to preserve this resource.

If we want to make an impact on musculoskeletalinjuries, we have to be willing to take different approaches. A workplace without injuries is possible.

Brian Halina is the president of Chemco Electrical Contractors Ltd.

P e r s p e c t i v e

by Brian Halina

Musculoskeletal InjuriesYes, You Can Reduce

at Your Company

Occupational Health & Safety Magazine is published three times a year, in January, May and September. Magazine policy is guided by the Occupational Health & Safety MagazineAdvisory Board consisting of industry and government representatives.

Occupational Health & Safety Magazine Advisory Board members:Wally Baer Alberta Human Resources and Employment, Workplace

Health and SafetyBob Cunningham Canadian Petroleum Safety CouncilBrent Dane Alberta Construction Safety AssociationLloyd Harman Alberta Forest Products Association Juliet Kershaw Paprika CommunicationsJane McCoy Alberta Human Resources and Employment, Communications Rose Ann McGinty Alberta Municipal Health and Safety AssociationBob Nebo Workers’ Compensation Board – AlbertaEd Sager Alberta Human Resources and Employment, CommunicationsRon Townsend Plumbers and Pipefitters Union

On occasion, this publication refers to the Occupational Health and Safety Act and itsregulations. In the event of a discrepancy between statements in this publication and theAct or regulations, the Act or regulations take precedence. Opinions expressed in thispublication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views or policy ofAlberta Human Resources and Employment or the Government of Alberta.

Subscriptions to Occupational Health & Safety Magazine are available without charge.When notifying us of a change of address, send an address label or subscription numberwith the new address.

Letters to the Editor We welcome response to articles or information published in thismagazine, as well as suggestions for future articles. We will print letters to the editor asspace permits. The editor reserves the right to edit letters.

Permission to reprint Copyright belongs to the Government of Alberta.

Occupational Health & Safety MagazineU Alberta Human Resources and Employment, Communications

10th Floor, 10808 - 99 AvenueEdmonton, Alberta T5K 0G5

S (780) 427-5585T (780) 427-5988toll-free connection within Alberta: 310-0000

For more occupational health and safety information, contact one of the regionalWorkplace Health and Safety offices:

Calgary (403) 297-2222Edmonton (780) 427-8848Grande Prairie (780) 538-5249Lethbridge (403) 381-5522Medicine Hat (403) 529-3520Peace River (780) 624-6162Red Deer (403) 340-5170

v or visit the Alberta Human Resources and Employment Web site: www.gov.ab.ca/hre

Design and layout by McRobbie Design Group Inc.Publication Mail Agreement No. 1528572 ISSN 0705-6052 © 2000

2 Yes, You Can Reduce Musculoskeletal Injuries at Your Companyby Brian Halina

11 Leading Safety in Residential Constructionby Norma Ramage

16 Chemical Confusionby Bill Corbett

18 Hydrocarbons on the Looseby Verleen Barry

12 The Invisible Injuryby Anne Georg

14 It’s All Up In the Air: Hazards of Fabricated Wood Productsby Debbie Culbertson

16 Border Crossingsby Diane Radnoff

14 News & Notes

18 Publications List

18 Courses & Training

19 Web Watcher

19 The Last Resort

20 Real World Solutions

20 Ergotips

22 In the Library

22 Calendar

23 Workplace Fatalities

M A G A Z I N E

O C C U P A T I O N A L

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 3

S t o r i e s

P e r s p e c t i v e

M u c h m o r e

P r o f i l e

A Workplace Health and SafetyAlberta Human Resources and Employment publication

Managing EditorJane McCoy

EditorJuliet Kershaw

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 04

N e w s & N o t e s

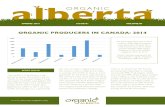

The Alberta lost-time claim rate continued its decline in1999, decreasing three per cent from 1998. Now standing

at 3.2 per 100 person-years worked, the rate is the lowest everrecorded in the province and translates to about 16 injuriesand illnesses per million hours worked. Data used tocalculate the rate are lost-time claims accepted by theWorkers’ Compensation Board – Alberta (WCB). About two-thirds of those employed in Alberta have WCB coverage.Exceptions include some agricultural, financial services andfederally regulated workers.

The rate of young workers getting hurt on the job lastyear continued high. Alberta Human Resources andEmployment’s Occupational Injuries and Diseases in Alberta, 1999Summary, points out that “the situation is particularly morealarming for young male workers, who are 85 per cent morelikely to be injured than other workers.” The manufacturingand processing, retail and wholesale trade, and constructionindustries accounted for over 65 per cent of lost-time claimsamong young workers.

While the lost-time claim rate for small business (thosewith fewer than 40 full-time employees) was about the sameas the provincial rate, it was about seven per cent higherthan those with more than 40 full-time employees.

Occupational fatalities accepted by the WCB totalled114. Of these, 33 per cent were incidents of occupational

Is training your business? Training agencies interested indelivering first aid courses in accordance with Alberta’s

new First Aid Regulation are invited to submit applications to Workplace Health and Safety for review.

Approved training agencies agree to a mandatory reviewof the course and training materials. Course curriculum isdetermined by Workplace Health and Safety’s director ofmedical services in consultation with a first aid standardsboard. Training standards and submission requirements are set out in the quality management plan found atwww.gov.ab.ca/lab/regs/faapp.html.

Send submissions to:Director of Medical Services9th Floor, 10808 – 99 Ave.Edmonton, AB T5K 0G5

Employers may continue using training agencies approvedunder the old regulation until December 31, 2000 — anextension of the original August 31, 2000 deadline.

For additional information, call (780) 415-8408.

Calling First Aid Trainers

1999 rate declines

lost-time claim

disease, 38 per cent were workplace incidents and 29 per centwere motor vehicle incidents.

Sprains, strains and tears continued to be the mostcommon type of lost-time injury, with the back the mostcommonly injured body part.

For more information, see Occupational Injuries and Diseases inAlberta, 1999 Summary, available at www.gov.ab.ca/hre or (780)427-8531.

Lost-time Claim RatesAlberta: 1991-1999

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

4.1

4.0

3.9

3.8

3.7

3.6

3.5

3.4

3.3

3.2

3.1

3.0

Watch for us will soon be available

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 5

OHSRegulatory Review

The ongoing Workplace Health and Safety (WHS) regulationreview will be completed by December 2000. Representatives

from industry, government and labour organizations arereviewing regulations governing explosives, noise, chemicalhazards, mine safety, radiation and ventilation, and the GeneralSafety Regulation. The new regulations will come into effect by thespring of 2001.

A task force set up for each regulation reviews identifiedissues and drafts proposals for a revised regulation. Drafts aremade available for stakeholder and public scrutiny and comment.All comments received are considered before a draft is finalized.

Discussion papers and proposals for the regulationsmentioned below are posted for review and comment on theWHS Web site: www.gov.ab.ca/lab/new/review.

For more information, call (780) 427-2687.

• General Safety Regulation, including provisions for fallprotection for roofers

• Chemical Hazards RegulationThe draft proposals have been completed and stakeholdercomments are now being reviewed.

• Mines Safety Regulation• Alberta Joint Work Site Health and Safety

Committee (JWSHSC) RegulationThe regulatory review is underway. A discussion paper has been released to employer and labour groups. Stakeholder comments are being reviewed before the regulatory proposal is drafted.

• Explosives Safety Regulation • Ventilation Regulation• Noise Regulation

The public consultations have been completed.

• Radiation Health Administration Regulation (under the Government Organization Act)The initial review phase is complete and a draft proposal hasbeen completed and released to stakeholders for review.

• Safety Requirements for Electric and Communication Utility Workers(a new component of the General Safety Regulation)The draft proposal is available for public consultation.

More regulations coming your way . . .

Update

Health and safety

A lberta will be sponsoring ten young workers to attend aYouth Health and Safety in the Workplace conference in

Ottawa this fall. The conference, scheduled from October 15through October 18, will bring together representatives fromunions, management, not-for-profit organizations, govern-ment and academia, along with young workers, to addressthe serious issue of the disproportionately high rates ofinjury to young workers. For more information, contactRobert Feagan at (780) 415-0608.

L ike employees in any hazardous workplace situation,those who work alone need to know how to protect

themselves and what support they can expect from theirsupervisors and employers. To ensure the safety of theseworkers, the Alberta government is preparing a regulation to address the hazardous nature of working alone. Theproposed regulation, based on recommendations of agovernment-industry-labour committee, will identifyemployer and employee responsibilities in situations wherepeople work alone. When the regulation is passed, aninformation handbook for employers and employees will be made available to the public.

for youth

Do you run a small business? And have you foundcreative ways of improving health and safety at

your workplace? Tell us your story and we’ll pass italong to our readers. We want to hear about yourpractices, methods, equipment modifications andmanagement concepts — anything that’s providedyou with a solution to a health and safety issue.Here’s your chance to make a difference to healthand safety at work sites across the province —urban or rural, office or oil lease.

Send your story [email protected]

What works

Protect those who work alone

for you?

on the Web! Occupational Health & Safety Magazine on-line at www.gov.ab.ca/lab/facts/ohs/index.html

Chemical Confu

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 06

Chemical Confuby Bill Corbett

What’s the difference betweenbuying solvent in a 170-litredrum from an industrialwholesaler or in a one-litrecan from a local hardwarestore? A whole lot of safetyinformation.

The 170-litre drum fallsunder federal legislation that requiresthe supplier to provide detailed labellingand Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS).By contrast, the one-litre can isconsidered a consumer product.Therefore, its sole safety instructionsmight be a centimetre of fine print and ahazard symbol.

Solvents are just one of manypotentially hazardous “consumerchemicals” that for various reasons aretreated differently, from a safetyinformation perspective, than industrialversions of the same products. Yet asurprising number of these consumerand other chemicals can find their wayinto the workplace. A companyemployee, for example, might head to anearby retail store to pick up a can ofpaint for touching up the shop walls, abag of cement for fixing a crack in theconcrete, a bottle of ammonia forwashing the staff kitchen floor or a jugof herbicide for spraying dandelions onthe company lawn. Because suchconsumer chemicals contain agents thathave the potential to cause everythingfrom skin irritation to cancer, it isimportant that employers and employeesbe aware of their hazards and treat themlike any industrial chemical.

“It’s a perception issue,” says DianeRadnoff, senior occupational hygienistand provincial Workplace HazardousMaterials Information System (WHMIS)coordinator with Workplace Health andSafety. “People think, ‘If I can buy it at alocal hardware store and take it home orbring it into the workplace, it’s not asharmful as the chemicals purchasedfrom industrial suppliers.’ Regardless ofwhere the chemical comes from, it canbe equally hazardous to the user.”

A two-tier labelling systemThe rationale behind the discrepancy inhazard information is that industrialchemicals commonly used in theworkplace pose a greater health risk thantheir consumer counterparts. “Thedifference addresses the fact thatworkers are often exposed for a greaterlength of time, such as using methanolthroughout an eight- or 12-hour shift.Most consumer products are not used tothis extent, are usually more diluted andare used in smaller volumes,” says Paul

Chowhan, a project officer in Ottawawith the Product Safety Bureau of HealthCanada. “If you’re using chemicals on aday-to-day basis, it is necessary thatworkers receive adequate training. AWHMIS-type training system forconsumer products would not befeasible.”

But Radnoff disagrees with the two-tier system. “Many of these products usethe same formulation,” she says. “Ifyou’re painting your house, you mightuse the same quantities of paint andthinner as an industrial worker would.”

The inconsistencies in informationrequired for various classes of chemicalscan also pose problems for the user.Indeed, figuring out which products arecovered by federal legislation and subjectto WHMIS information requirements andwhich fall under other regulations withdifferent requirements can be asconfusing as the chemistry behind the products.

The classification of a product isoften a complex process. A “controlledproduct” is subject to WHMIS’sinformation requirements. A “restrictedproduct” for consumer consumption insmaller quantities is exempt fromWHMIS rules for labelling and MSDS.Examples of exempt products packagedfor retail sale include bleaches andcleansers containing chlorines, corrosivechemicals such as hydrochloric acid, andturpentine.

A number of other productscontaining the same chemicals can enterthe workplace with exemption fromWHMIS requirements because they arecovered under legislation other than thefederal Hazardous Products Act (HPA).Cosmetics, for example, come under theFood and Drug Act, and pesticides underthe Pest Control Products Act. Each law hasits own health and safety informationrequirements. As a result, acetone isexcluded from HPA requirements whensold in a nail polish remover butincluded when used in an industrialsolvent. Similarly, Stoddard solvent canbe found in both an excluded herbicideand an included industrial solvent. Tofurther confuse the issue, products thatexempt the supplier from providingWHMIS labelling and MSDS do notexempt employers from providingemployee training programs because thismatter comes under provinciallegislation.

Need recognized for greaterregulatory consistency“Often, workers face a hodgepodge ofinformation,” says Radnoff. “If theproduct is considered a controlled

People think, ‘If I can buy itat a local hardware storeand take it home or bring itinto the workplace, it’s notas harmful as the chemicalspurchased from industrialsuppliers.‘

usion The simplest solution, suggestsRadnoff, is not allowing anychemicals exempt from WHMISlabelling or MSDS requirementsonto the work site. “If you can avoid bringing these things in, youshould. But it’s hard to control. Ifthese products are used or stored at the work site, it’s the employer’sresponsibility to obtain theinformation required for their safeuse and handling, and to train theworkers at their work site appropriately.”

Bill Corbett is a Calgary writer.

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 7

Farm ChemicalsAlberta farmers are largely exemptfrom the rules of the WorkplaceHazardous Materials InformationSystem (WHMIS). As a result, manyworkers on the province’s 60,000farms are unaware of the proper wayto handle potentially toxic chemicals.

“Most farmers are familiar withthe hazards of pesticides becausethey use them so much,” notes EricJones, senior farm safety specialistwith Alberta Agriculture, Food andRural Development (AAFRD). Still, ina lot of cases they don’t protectthemselves properly. “My majorconcern,” says Jones, “is with all theother chemicals used on farms, likeVarsol and petroleum products. In anindustrial setting, these productswould be covered under WHMIS.Some farmers still wash their handsin gasoline. When I tell them it’scarcinogenic, they say it’s okaybecause they wash in unleaded gas.

“A lot of farm chemicals are alsonot stored properly. Dairy operationsuse large quantities of ammonia andother cleaning agents to wash theirequipment. You’ll often find thesechemicals just piled together in acorner. Some farmers buy paints andpesticides on special and then storethem for the winter in the basementof the house. These chemicals canpermeate through metal containersand get into the ventilation system.”

Jones says some progress isbeing made. He is working withAlberta feedlot operators to developsafer chemical handling practices andto provide WHMIS training for theiremployees. He convinced one feedlotto switch its indoor heaters fromkerosene — which can affect thenervous system — to natural gas.“Younger farmers know they have toprotect themselves better or theycould die like some of their fathersdid,” says Jones, whose uncle died oflip cancer in his 50s.

For more information on safe handlingof agricultural chemicals, contactAAFRD’s Farm Safety Program at (780) 427-2171 or see www.agric.gov.ab.ca

usion

product, label and MSDS content mustcomply with the requirements set out in thecontrolled products regulations. But if it’s apesticide or a consumer product, it’s coveredunder different legislation and there’s norequirement for the supplier to provide anMSDS for the product.”

The federal government is reviewingsome of this legislation to bring greaterconsistency to the regulation of hazardouschemicals. For instance, consumer chemicaland container regulations are moving tomore of a WHMIS-style, criteria-based classifi-cation system, which will focus more on thehazard of the total product rather than on itsindividual components.

Employers can do several things tolessen the risks related to consumer andother non-controlled products that entertheir workplace. First, they can requestmanufacturers or suppliers of such productsto provide them with MSDS. “Most suppliersare very good about providing informationabout products,” says Radnoff.

Employers can also provide their ownwarnings for chemicals excmpt from WHMISrules. “There’s nothing to stop employersfrom creating their own labels to put on top,”says Chowhan. “They can educate theirpeople on the proper use of these chemicals.”In fact, this is a requirement under Alberta’sChemical Hazards Regulation.

R e s o u r c e s

If you’re using chemicals ona day-to-day basis, it isnecessary that workersreceive adequate training.

WEB LINKS

www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hpb/transitn/index.htmlFacts from Health Canada.

canada.justice.gc.ca/STABLE/EN/Laws/Chap/H/H-3.htmlCanada’s Hazardous Products Act.

canada.justice.gc.ca/STABLE/EN/Laws/

Chap/F/F-27.htmlCanada’s Food and Drug Act.

www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ehp/ehd/who/psb.htmHealth Canada’s product safety information.

www.ohsu.edu/croet/links.htmlThe Center for Research on Occupational andEnvironmental Toxicology links to a variety ofoccupational health subjects and resources.

IN THE ALBERTA HUMAN RESOURCES AND EMPLOYMENT LIBRARY

IARC Monographs on the Evaluation ofCarcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 57Lyon, France: IARC, 1993(RC 268.57 In8 v. 57 1993)

Occupational exposures of hairdressers and barbers,personal use of hair colourants, some hair dyes,cosmetic colourants and industrial dyestuffs.

IARC Monographs on the Evaluation ofCarcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 63Lyon, France: IARC, 1995(RC 268.57 v. 63 1995)

Dry cleaning and some chlorinated solvents, andother industrial chemicals.

IARC Monographs on the Evaluation ofCarcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 65Lyon, France: IARC, 1996(RC 268.57 In8 v. 65 1996)

Printing processes and printing inks.

by Verleen Barry

Hydrocarbo

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 08

Your son is a smart, responsibleyoung man with his futurebefore him. To earn money toattend university in the fall, hehas taken a summer job as alabourer for a gas company,working on a drilling site.

Then, in a fraction of asecond, his life and yours are changedforever. In a workplace fire caused byhydrocarbons in the atmosphere, yourson sustains third-degree burns to 85per cent of his body. He is taken tohospital and the doctor tells you thathis chances of survival are slim.

A lack of hydrocarbonawareness, training andhazard detectionmethods has caused toomany tragic incidents.

Hydrocarbo

A thousand questions run throughyour mind, all with no answers. “Whymy son? How did he get into ahazardous area? What measures weretaken to alert workers to the hazards?”

Although this story soundsdramatic, all too often it is a sad realityfor workers and their families.

Detecting and controlling hydrocarbonsUnder certain circumstances, hydrocar-bons, such as methane, butane orpropane, become flammable (seesidebar, “Hydrocarbons”). Hydrocarbonsare a major hazard on oil and gasindustry work sites because the vapourshide in confined spaces, pool in low-lying areas or become airborne whensludge is disturbed and disperse intothe atmosphere.

With the technology andinformation available today, allowingthese hazardous situations to exist isunacceptable. Therefore, Alberta’sGeneral Safety Regulation requiresemployers to evaluate “the potential forcreating an explosive atmosphere”when storing, handling or processingflammable substances. If such anevaluation determines that hydrocar-

Government takes actionBecause of the number of firesoccurring on lease sites,Workplace Health and Safety(WHS) is working with industry toimprove awareness of hydrocarbonhazards. The WHS oil and gasprogram, launched in July 1999, is geared toward the drilling andservicing industry. If an on-siteWHS inspection reveals a highhazard of uncontrolled andunmonitored release of hydrocar-bons, the site will be shut downand a stop-work order issued untilthe condition is corrected.

ns

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 9

bons may be released into the atmosphere and present arisk of a flash fire or explosion, the employer is required todevelop appropriate procedures and precautionarymeasures. In other words, workers have to be competent toaddress hydrocarbon hazards safely.

Employers might choose to use engineering controls;for example, routing hydrocarbons to a closed system suchas a pressure vessel or flare. A pressure vessel removes theliquids and solids and routes the gas to a flare where thehydrocarbons are safely burned. Alternatively, if a smallamount of hydrocarbon is released (for example, whendraining a pump) employers could remove workers and allignition sources from the area while the hydrocarbons arereleased (an administrative control). Installing ahydrocarbon gas detector (an equipment control) is anotheroption. Hydrocarbon detection is an effective means ofensuring the work area is free of hydrocarbons, as you can’trely on smell, visible vapours or atmospheric conditionssuch as wind to detect or control the gases.

Hydrocarbons as hazardous as H2SMost workers are well aware of the dangers of hydrogen

sulfide (H2S) and can use detection and personal protectiveequipment to address them effectively. Unfortunately,however, when working on wells that do not contain H2S(sweet wells), workers tend to become complacent anddevelop a false sense of security. The belief that sweet wellsare not as dangerous as sour wells has to be dispelled.

Following are just a few examples of incidents thatoccurred at sweet wells in 1999. In some cases, the injurieswere minor, but there was clearly potential for seriousinjuries or fatalities.• A water truck pulled up to a rig tank while the well was

circulating (pumping fluid into the well). The truckengine ignited hydrocarbons coming off the tank as thefluid flowed back up the well. Two workers received burnsto the hands and face.

• Workers used a torch to thaw a pipe on a production tank.They left the torch burning while they removed ice from the valve on the tank. Hydrocarbons escapedfrom the tank and ignited, burning one worker’s hands and face.

HydrocarbonsFires and explosions in the oil and gasindustry are often caused by hydrocarbon vapours.A combination of hydrocarbon vapour and oxygencontacting an ignition source can cause a fire or explosion.

Hydrocarbons (such as methane, butane orpropane) are compounds of hydrogen and carbonatoms. Processes used in the oil and gas industrycan release vapours into the atmosphere.

So-called sweet wells produce hazardousvapours. Sour wells produce hydrogen sulphide(H2S), which not only is toxic but also is highlyflammable. Methane, like H2S, mixes with air,becoming extremely flammable.

To prevent fires or explosions at oil or gasdrilling, servicing or processing sites, know theflammable or explosive limits of hydrocarbons andmonitor the atmosphere for their presence.Hydrocarbons are explosive within the rangedefined by these limits. A limit is the percentage ofhydrocarbon, by volume, in the air-hydrocarbonmixture. For example, when exposed to air,methane has a lower explosive limit (L.E.L.) of 5.0%and an upper explosive limit (U.E.L.) of 15.0%. Anyair and hydrocarbon mixture in this range willburn or explode.

Sources of ignition in a workplaceinclude (but are not limited to):• welding• cutting• friction• internal combustion engines• sparks from faulty electrical systems• cigarettes• lightning• auto-ignition• pyrophoric iron sulphide• spent catalyst

When dealing with mixtures of hydrocarbons,such as a combination of methane, propane andbutane, handle them according to the propertiesof the most hazardous component, in this case,butane. When mixed with air, butane has an L.E.L.of 1.9% and an U.E.L. of 8.5%. Butane will combustwhen its percentage within the hydrocarboncompound falls within the L.E.L. and U.E.L, and isin a vaporized state.

ns on the loose

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 010 O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • M A Y 2 0 0 0

• A vacuum truck hooked on to a vessel containing propaneand pulled air into the vessel. The air mixed with thepropane, creating an explosive atmosphere in the vessel.The resulting explosion blew open the door on the vesseland burned four workers on the hands and face.

• Workers were welding a vent on a truck that had hauledwater pumped out of a production well. The residue ofthe produced water emitted hydrocarbons that explodedwhen the welding started. Two workers were killed in theexplosion.

Investigation of the incidents revealed these causes:• Workers were not trained to an appropriate level of

competence. • The workers didn’t know about the hazards of the job or

safe procedures.• Supervision was inadequate.• A supervisor asked workers to perform a task that put

them in a dangerous situation.• Hydrocarbon detection methods were not used.

A lack of hydrocarbon awareness, training and detectionmethods has caused too many tragic incidents, and it’s timeto take action.

(For details of the legislation pertaining to hydrocarbonhazards, refer to the General Safety Regulation, sections 178and 179.)

Verleen Barry is an occupational health and safety officer withWorkplace Health and Safety (WHS). She is the northern regionalcoordinator of the WHS oil and gas program.

Hydrocarbon safety checklist for employers• Engineering, administrative and personal protective

equipment controls• Adequate safety training programs• Adequate supervision• Hazard assessment• Pre-job meetings• Up-to-date, standard operating procedures• Orientation for new workers to company safety

policy and procedures• Properly maintained and calibrated hydrocarbon

detection equipment• Established lockout and isolation, hot-work and

confined-space entry procedures

Steps to prevent hydrocarbon-related incidentsEmployers must: • Train workers. Include orientation to the

company’s safety policy and information about safeworking procedures. Ensure that workers knowabout the hazards they are likely to encounterduring a job and how to handle those hazards.

• Conduct a hazard assessment on the job to bedone. Hold a pre-job meeting and inform workers ofthe potential hazards.

• Ensure that a job involving hot work has beenproperly prepared. Has the area been ventilated,purged, isolated, blinded and gas-checked before thejob is started? Shut down or control all sources ofignition (for example, engines or smokingmaterials). Ensure that the gas detector is properlymaintained and calibrated, and that workers usingthis equipment are trained and competent.

• Ensure that workers comply with the OccupationalHealth and Safety Act and its regulations as well asthe company’s own safety policies. Supervisors onthe site must be knowledgeable about properprocedures for the job or task. With increasedactivity on lease sites, we are seeing younger, lessexperienced crews. Comprehensive training of theseworkers is critical. Supervisors must ensure that allworkers are trained to react appropriately inhazardous situations.

The belief that sweet wells arenot as dangerous as sour wellshas to be dispelled.

WEB LINKS

hazard.com/msds/index.htmlThe University of Vermont’s SIRI (Safety Information ResourcesInc.) MSDS collection. Search for "hydrocarbon" or "hydrocarbons."

www.dupont.com/safety/esn98-1/oil+gas.htmlSafety information from DuPont.

R e s o u r c e s

residential construction

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 11

meetings. Late last year, the company decided to formalize itssafety practices in a manual. However, Amir says now, it becameclear that “unless we were really forceful we couldn’t get peopleto follow the manual. We felt we couldn’t be forceful enoughunless we had somebody devoted to safety full time.”

Fortunately, Amir had the right person available in DeVereViola, an eight-year veteran construction manager with thecompany. As safety officer, Viola visits each Avi site every weekto ensure compliance with the Occupational Health and Safety Act.He also undertakes occasional special projects such as thisyear’s Calgary Stampede show home.

Viola admits that enforcement is “tough,” partly becausehis job is very new. “Down the road, once we get this programimplemented, I think it will be a plus for the company.” Violasays he has already received “really good feedback” fromhomeowners.

For now, Viola keeps on persuading and negotiating wherehe can, and getting tough when he has to. If employees and sub-contractors ignore his suggestions, he reports the matterdirectly to his operations manager or to Amir. “Avi wants us togo at this 100 per cent,” he says.

Ray Cornez, team leader with Workplace Health and Safetyin Calgary, says one plus of an in-house safety officer like Violais his hands-on experience with the residential buildingindustry. “Our inspectors cover all industries. We can’t beexperts in any one area. A company safety officer who knowsthe business also knows the problems people can encounter onthe job.”

Amir thinks that once his competition knows what hiscompany is doing, the larger builders will follow his example.He says the costs are minimal, and there’s great personal andprofessional satisfaction in running a safe company.

Norma Ramage is a freelance writer and communicationsconsultant living in Calgary.

It’s obvious to anyone who has ever watched a home beingbuilt that there are dozens of potential safety hazards in

the work. While there are no provincial regulationsrequiring any construction company to employ a full-timesafety officer, the owner of Calgary’s Homes by Avi hopes toset a trend for just that.

Avi Amir would like to walk on to any building site inAlberta and see every tradesperson working safely. “Safety isan important part of our business,” says Amir, “and I take itvery seriously.”

Earlier this year, Homes by Avi became the firstresidential homebuilder in Alberta to employ a full-timesafety officer. This person’s job is to visit the sites of the 300-plus homes the company builds each year in Calgary andEdmonton to ensure compliance with provincial safetyregulations. If any tradespeople are in violation, says Amir,“we call the subcontractors and tell them they must fix theproblem. People will risk their positions with us if theyignore our safety officer and tell him to go away.”

Grant Ainsley, executive director of the Alberta HomeBuilders’ Association, says the more usual approach of theprovince’s residential builders is to make safety the part-time responsibility of a construction manager, superin-tendent or other employee. Inspectors with WorkplaceHealth and Safety also conduct site compliance checks. Sowhy is Homes by Avi the first residential builder to appoint asafety officer? The monetary paybacks such as reducedWorkers’ Compensation Board – Alberta (WCB) payments areless substantial for residential builders with small numbersof employees than for the larger commercial builders, saysAinsley. Most residential builders require their subtrades tocarry their own WCB coverage. At Homes by Avi, subcontrac-tors make up 90 per cent of the workforce.

Amir says he didn’t consider potential reductions inWCB costs when he instituted the program. “It would befalse to say that we’re doing this because somebody will giveus money at the end of the day,” he states. “We’re doing itbecause we should, and because it improves the way we dobusiness.”

Amir agrees, on the other hand, that establishing areputation as a safe workplace will likely help his companyattract and keep top people, even in today’s overheatedconstruction industry.

Having a reputation for safety is good public relations,Amir says with a smile. “Overall, if we can establish ourselvesas a safe company, it will be one more push for Homes by Aviin the marketplace. Good people will want to work for usand families will want us to build their homes.”

Before the appointment of a full-time safety officer,safety practices at Homes by Avi were less formal. The focuswas primarily on safety discussions at weekly construction

by Norma Ramage

residential constructionLeading safety in

We’re doing it because weshould, and because it improvesthe way we do business.

P r o f i l e

only one task and at amuch faster rate,” sheexplains.

Martin estimatesthat workers whopackage tissue repeat asix-to-seven-second taskcycle for eight hours aday. There may be two to three stressful wrist motions per cycle.In one minute, the worker performs 20 to 30 stressful wristactions. That translates to 1,200 to 1,800 stressful wrist actionsper hour.

Workplace Health and Safety reports that in 1999 MSIsinvolving the back, upper limbs, wrists and hands accounted for29.5 per cent of all lost-time claims. Overexertion injuries werealmost twice as great as the next injury category.

To reduce the current high level of MSIs, Workplace Healthand Safety advises employers to redesign workstations, reducethe awkward body positions that workers adopt to performtheir work, and reduce or eliminate repetitive movements.Many of these changes cost little or nothing to implement, and they prevent the substantial costs resulting from time lost due to injury.

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 012

Assembly line workers on the Cargill Foods production floor do a lot of laborious and heavywork. On the slaughter floor and fabrication floor,workers handle animal carcasses and cut them upinto a variety of marketable cuts. The tools they useare knives and hooks.

Because of the repetitive and physical nature oftheir jobs, the slaughter and fabrication floor

workers represented an unusually high percentage of injuriesin the company. From 1996 to 1998, carpal tunnel syndromeand trigger finger (see “Definitions” page 13) were responsiblefor 46 surgeries among Cargill’s 1,735 production workers. Cargill recognized the impact these surgeries were having onproductivity. The company entered into an innovative seven-year-long research program involving the University ofCalgary Faculty of Medicine, an occupational therapist and afull-time research assistant who is still working at Cargill.Their research determined that trigger finger in the meatindustry in Alberta costs approximately $6.63 millionannually.

As a result of that research, two sizes of hooks weredesigned to accommodate varying hand sizes. The tool wasalso redesigned to reduce pressure on the wrist.

Other ergonomic practices were instituted as well, including:

• an extensive database that is used to analyze commoninjuries

• new hiring practices that match a potential employeewith appropriate tasks

• training to emphasize employee alertness and individualresponsibility for minimizing risk on the job“In 1999 no surgeries were required, and in 2000 only

two surgeries can be attributed to repetitive strain injuries,”reports Kev Auty, safety manager at Cargill’s High River plant.These improved musculoskeletal injury (MSI) statistics clearlyshow the value of the changes made.

Cargill is bucking the trend. Experts agree that incidentsof MSI are on the rise. “MSIs are becoming more common asthe workforce ages,” says Linda Martin, ergonomic consultantwith Ergo Works Inc. in Edmonton. “Workers are not as ableto endure repetitive strain on the job and do not recover fullyfrom injuries.

“Even though industry thought mechanization wouldreduce the workload,” says Martin, “increased automationmay often require the individual to perform more repetitivemotions.” Martin uses assembly-line workers who packagetissue as an example. These workers traditionally performedfour or five tasks. “With increased mechanization, workers do

Many companies see thevalue of adapting theworkplace to the workers,recognizing that the bestsolutions for preventingMSIs come from theworkers themselves.

The

InjuryInvisible

by Anne Georg

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 13

How employers can reduceMSIs on the assembly line• Reduce time stress by relaxing deadlines

and examining incentive programs thatmay contribute to workers’ stress.

• Facilitate job rotation. Have workers do avariety of tasks requiring differentactions.

• Ensure that equipment is designed forease of operation. Take into accountbending, reaching and twisting motions.

• Design tools for the workers. Considerworkers’ different sizes and body types.

• Adjust lighting and temperature tooptimize comfort.

• Have workers take frequent breaks.

• Hire an ergonomic consultant to analyzethe tasks workers are performing.

• Consult resource materials availablethrough the Internet and WorkplaceHealth and Safety.

How an employee canreduce MSIs on theassembly line• Be aware of the actions required to do

a job.

• Identify steps that cause stress, and tellsupervisors about them.

• Do stretches designed to alleviate stressresulting from a particular task.

• Maintain a reasonable degree of fitness.

• Take breaks as often as possible. Take time for lunch.

Injury is often the result of amismatch between the demands of thework tasks and the worker’s ability tomeet those demands. A worker may bephysically overloaded by the necessity ofrepeating one motion thousands of timesduring a shift.

Many companies see the value ofadapting the workplace to the workers,recognizing that the best solutions forpreventing MSIs come from the workersthemselves. Companies are redesigningworkstations and tools to reduce awkwardrepetitive motions. They are trainingworkers to use the proper posture for thetask, identifying repetitive stresses,rotating tasks so workers are not doingthe same task all day and encouragingworkers to take frequent breaks.

The Goodyear Tire assembly plant inMedicine Hat uses a training processcalled Objective Base Training (OBT) toensure that its workers minimize the riskof MSIs. This process involves analyzingeach task and categorizing it by physicalmovements. Workers (called “associates”at Goodyear) go through the OBT with atrainer. They discuss what the job entailsand how to do it safely. An accompanyingOBT manual outlines specific key safetypoints that help both new andexperienced associates do their jobs safely.

Associates are certified within two tothree weeks of starting their new job, andre-certified every year. As a result, theyunderstand the essential job functions aswell as the importance of safety. Startingin September, associates will be trained inergonomic awareness and how to preventincidents that involve ergonomics.

“The OBT includes quick stretchesthat help prevent repetitive straininjuries. Associates are in the beginningstages of using these stretches during theworkday,” says Craig Hiebert, the healthand safety manager at Goodyear Tire inMedicine Hat.

Both Goodyear and Cargill haverecognized the importance of preventingMSIs on their assembly lines. Preventionprograms like the ones these companieshave implemented are meaningful stepstoward countering the trend towardincreased incidents of MSI.

“MSIs don’t kill workers, but they canhave a devastating impact on their livesand their livelihood,” says Ray Cislo,safety engineering specialist at WorkplaceHealth and Safety. “A worker in pain can’t

DefinitionsCarpal tunnel syndrome: damage to anerve passing through the wrist to thefingers

Trigger finger: inflammation of tissuesaround the tendons of the finger thatlimits movement of that finger

WEB LINKSwww.med.viginia.edu/medicine/clinical/orthopaedics/admusc.html Describes various musculoskeletal disorders.

www.discoveryhealth.comLook up health@work. The site includes adesk exercise of the day for relief frommusculoskeletal strains and stresses.

www.cdc.gov/niosh/93-101.htmlNational Institute for Occupational Safetyand Health’s (NIOSH) national strategy foroccupational musculoskeletal injuries.

www.ergoweb.com/Comprehensive ergonomic information.

IN THE ALBERTA HUMAN RESOURCES AND EMPLOYMENT LIBRARY

BooksMusculoskeletal Disorders inSupermarket Cashiersby Colin MackeySuffolk, UK: HSE Books(RC 925.5 M32 1998)

Ergonomics Program ManagementGuidelines for Meatpacking Plants Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor(TS 1970 E73 1990)

WORKPLACE HEALTH AND SAFETY PUBLICATIONS

Musculoskeletal Injuries Parts 1 through 6Alberta Injury Statistics and Costs(ERG017)Symptoms and Types of Injuries (ERG018)Biomechanical Risk Factors (ERG019)Workplace Risk Factors (ERG020)Assessing Ergonomic Hazards (ERG021)Reducing Ergonomic Hazards (ERG022)

Order throughwww.gov.ab.ca/lab/facts/ohs/index.html or by phoning any of the WHS regionaloffices. (See page 2 for a list of offices.)

R e s o u r c e s

concentrate. The quality and produc-tivity of their work decreases. Aworker with damaged nerves maybecome clumsy. Those things affectthe company’s bottom line, andthey’re taken home to the worker’sfamily. MSIs are a serious problem.”

Anne Georg is a writer and communica-tions consultant who works from her homebase in Calgary.

It’s All Up In

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 014

On a hot summer day in July, Iam setting treated fence postsinto the ground around ouracreage. I wear thick gloves toprotect my hands from thechemicals used to treat thewood. As I work, it strikes methat workers who prepare

secondary forest products must takemuch stronger protective measuresthan weekend carpenters like me.

According to the Alberta ForestProducts Association (AFPA), themanufacture of forest productsaccounts for 20,000 jobs in theprovince. Companies produce lumber,pulp and paper, panelboard — mediumdensity fibreboard (MDF) and orientedstrandboard (OSB) — and secondarymanufactured products such aschemically treated wood products.

Henny Lamers is the manager ofhealth, safety and environment atRangerboard, a division of West FraserMills. The Whitecourt companyproduces 120 million square feet ofmedium density fibreboard (MDF) eachyear. The product is used in makingkitchen counters, cabinets, furnitureand flooring. To produce MDF,softwood fibres are put through amechanical refining process.

“The fibres are refined usingsteam,” says Lamers. “Urea-formalde-hyde resin is added to the wood fibre,and it becomes a waxy dry mass.” Thismass is then formed into a mat andpassed through a giant multi-openingpress. The press is roughly 10 feet wideand 30 feet high. One worker operatesthe press from within an enclosedcontrol room. Another worker spendsabout an hour a day cleaning thepress. This is a demanding job. Thepress gets extremely hot duringoperation. Wood dust produced by the

refining process sometimes settles onthe press and must be removed toavoid the risk of fire. An air hose isused to remove these excess fibresfrom the machine.

When the press opens intermit-tently to release pressure, formalde-hyde vapour and fine wood fibre arereleased into the air. Formaldehydeproduces a colourless, strong-smellinggas. At low concentrations it can causewatery eyes, nausea, coughing andchest tightness. Formaldehyde hascaused cancer in laboratory animalsand may cause cancer in humans.

Chemical emissions and exposureAt Rangerboard, workers may usehand-held monitors to check the levelsof formaldehyde gas in the plant. Thecompany also regularly monitors airquality. Formaldehyde concentrationsusually fall well below the permissibleexposure limit of 2 ppm (parts permillion). However, peak exposuresabove the 2 ppm limit do occur. Whenthe hot formaldehyde vapour isreleased from the press, the exhauststream flows upward. An employeewho is cleaning the top of the presscould be working right in the routetaken by the stream. Lamers says thatthese workers must wear full-facecartridge respirators. “The mask hascartridges that filter out formaldehydegas and wood dust,” he explains.

Other forest product manufac-turers face air quality challenges aswell. Spray Lake Sawmills of Cochranemanufactures chemically treated wood products like my fence posts.According to safety and environmentalcoordinator, Howard Pruden, thecompany uses a “full cell pressurizedtreatment process.” Plant staff useenclosed forklifts to load lumber ontocarts. The carts are moved along

How employers canlower the risksinvolved in theproduction of woodproducts:• Implement strong industrial

hygiene procedures, such as dailyfloor cleaning.

• Establish personal protectionregimes (e.g., ensuring that glasses,gloves and protective clothing areworn at all times).

• Control exposure by rotatingemployees to different jobs.

• Provide mechanical safeguards suchas ventilation and dust extractionsystems.

• Monitor and maintain equipment.

Protect yourself whenworking near dust orchemicals from woodproducts:• Use a dust mask appropriate to the

toxic substances being used.

• Change clothing frequently.

• Wear rubber gloves and protectiveeyeglasses.

• Wash hands after removing glovesand clothing.

by Debbie Culbertson

It’s All Up In Hazards of Fabricated Wood Products

“The staff wear rubber gloves andglasses, and they change their coverallsfrequently,” says Pruden. “We do airmonitoring once a year and biologicalsampling of staff to see if they’re beingaffected. We also rotate staff to otherfunctions.”

Controlling exposure to wood dustPruden says that keeping airborne dustto a minimum is also important in thelargest part of Spray Lake’s operation —its sawmill. Exposure to wood dust occurs at all stages of wood processing.According to Workplace Health andSafety, many types of wood containchemicals that can irritate the eyes,nose and throat. Workers exposed tosome softwood dusts are also at risk ofdeveloping reduced lung function anddermatitis (an inflammation of theskin).

Spray Lake uses a vacuum systemto minimize airborne dust in thesawmill. It works like the centralvacuums used in homes. A long tube isplaced near the cutting saw. This tubeis attached to a central fan mechanismthat generates suction. As lumberpasses through the blades, fineairborne dust is drawn into the tube.Heavier sawdust drops beneath the

railway tracks into a long, pressurizedcylinder. The cylinder doors are closedand a vacuum is introduced into thechamber. Then it is flooded with achemical solution made up of 98 percent water and 2 per cent chromatedcopper arsenate (a mixture of arsenic,hexavalent chromium and copper). Thecylinder is pressurized for two to threehours. The solution is drained off, to bereused later.

Like the workers at Rangerboard,Spray Lake staff must guard againstshort-term peak exposures to toxicsubstances. For instance, when thetreatment cylinders are opened,residue left from the treatment processis dispersed into the air. It eventuallyaccumulates on the floor. If thisresidue isn’t removed, it can be stirredup into the air whenever equipment orstaff move about on the plant floor.

At Spray Lake, workers keep theresidue under control by washing thefloor of the treatment plant every daywith a high-pressure hose. There’s onlyone other time that they come intodirect contact with the treatedproducts: when they unchain the woodfor transport after it has been releasedfrom the cylinder. Fortunately, apersonal protection regime is in placeto limit exposure in these situations.

the Air

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 15

WEB LINKSwww.ohsu.edu/croet/links.htmlCROET (Center for Research on Occupational andEnvironmental Toxicology) provides links to avariety of hazards related to wood products andpulp and paper safety.

www.cdc.gov/niosh/nasd/docs2/as13200.htmlOccupational Safety and Health Administration’s(OSHA’s) exposure standard for wood dust.

R e s o u r c e s

the Air

blades onto conveyor belts. Later, theheavy sawdust is combined with thefiner material and is bagged and soldto other manufacturers.

Spray Lake has invested $220,000into their vacuum system. While thecompany doesn’t benefit financiallyfrom the equipment, Pruden says thatSpray Lake managers believe that “thebiggest return is the health of ouremployees.”

A recent study by the NationalInstitute for Occupational Safety andHealth (NIOSH) indicates that NorthAmerican wood treatment plants havea good health and safety record. As Ifinish my fencing job, it’s good toknow that these manufacturers likelyhaven’t left safety up in the air.

Debbie Culbertson is a writer and editorliving in Devon, Alberta.

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 016

Approximately 90 per cent ofthe work sites in Alberta aregoverned by the AlbertaOccupational Health and SafetyAct and its regulations. Theremaining 10 per cent fallunder the jurisdiction offederal laws, namely the

Canada Labour Code, Part II, and theCanada Occupational Safety and HealthRegulations. Understandably, there isoften some confusion about whichindustries in the province come underwhich legislation.

Three key questions need to beanswered in determining thejurisdiction of a particularoperation:1. Does the purpose of the business

involve moving people, goods orcommunication beyond provincial orinternational borders (for example,busing, trucking or television)?

2. Has the business been deemed to befor the “general advantage ofCanada” (for example, the grainbusiness)?

3. Is the worker governed by federal orprovincial legislation?

The third question is usually the mostdifficult. For example, construction asan industry falls under provincial juris-diction, but what happens when aprovincial construction company iscontracted to build a grain elevator?During the construction phase, theconstruction workers are still underprovincial jurisdiction. But afterconstruction is complete, theemployees of the grain company whomove in fall under federal jurisdiction,since grain elevators are regulatedfederally, and thus the employees ofthe grain elevator will be regulatedfederally.

If a provincial constructioncompany is hired to come on site to dorenovations or other work once theelevator is operating, these construc-tion workers are still regulated provin-cially. However, the constructioncompany also needs to comply with

federal legislation that governs thework site.

As a general rule, if you’reworking for a company that is provin-cially regulated on a site that isfederally regulated, you should complywith the more stringent legislation —especially if you’re unsure aboutwhich legislation applies.

Keep in mind that provinciallyand federally “incorporated” does notmean the same thing as federally orprovincially “regulated.” For example,department stores such as the Bay orSears are federally incorporated, butthey are regulated by provinciallegislation because they carry and selltheir own merchandise (i.e. are not“common carriers”).

For more information or to verifyjurisdiction, contact one of theWorkplace, Health and Safety regional

offices (listed on page 2) or HumanResources Development Canada.

Diane Radnoff is a senior occupationalhygienist and provincial WHMIS coordinatorwith Workplace Health and Safety.

WEB LINKS

www.cupe.ca/doc/990209-1.html Concerns about change in jurisdiction for safetyfrom federal to provincial regulations for a mine.

www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/information/govt.html#_1_1 List of federal and provincial departmentsresponsible for occupational health and safety.

www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/legisl/intro.html An article from CCOHS about who does what interms of oh&s legislation in Canada.

info.load-otea.hrdc drhc.gc.ca/~legweb/homeen.shtml Legislation that falls under federal jurisdiction.

R e s o u r c e s

by Diane Radnoff BorderBorder

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 17

Federal Jurisdiction

Federal public service and Government of Canada crowncorporations (e.g., HRDC, Canada Post, CMHC)

A railway, canal, telegraph or other work or undertakingthat connects one province with another or extends beyondthe limits of one province

Railroads that cross provincial boundaries (e.g., CN, CP Rail)

Road transport: interprovincial trucking companies (carriersthat transport other people’s goods) and their facilities(warehouse, maintenance garages)

• This category includes buses, couriers, movingcompanies and oil-field haulers that are commoncarriers or do interprovincial trucking (e.g., CanadianFreightways, Tri-Line, Jo-Ann Trucking).

Buses and couriers (e.g., Greyhound, Brewsters, UPS,Purolator)

Aeronautics: passenger or cargo airlines, aircraftmaintenance companies, most airside operations such asbaggage handlers and refuelers, security services for pre-board screening and air traffic control

• If carrying passengers or freight is an integral part ofthe airline operation, it is regulated federally (e.g.,Hudson General, PLH Aviation Services, NavCan).

Oil and gas pipelines that pass over provincial or interna-tional borders (administered by the National Energy Board),including pipeline head offices and compressor stations, andoffshore drilling and production if they fall within an aspectof shipping in Canadian waters

All grain elevators and most feed mills, flour mills, feedwarehouses and seed cleaning mills (e.g., Martin Pet Foods,Landmark Feeds, Masterfeeds, Cargill feed mills, Agricoreelevators)

All chartered banks (e.g., Bank of Canada, Bank of HongKong)

Telecommunications: telephone companies and mostnational paging companies (e.g., Telus, AT&T)

Broadcasting jurisdiction determined with respect tohertzian waves (e.g., Shaw, City Cable, WIC Communications)

First Nations: band employees and industries that benefit theband

Uranium mining

Provincial Jurisdiction

Provincial public service and provincial crown corporations

Short-haul railroads that operate within the province (e.g.,ProCar, PDS Railcar Service, Central Western Railway, StettlerShort Line)

Road transport: companies that transport their ownproducts, even if they cross provincial borders (e.g., Safeway,Sears, The Brick)

Buses and couriers (e.g., school buses, city buses, localcouriers, bicycle couriers)

Aircraft component manufacturers, retail shops andrestaurants located at an airport (e.g., Sky Chefs, CanadianTurbine, United Technologies)

Pipeline construction and maintenance (e.g., constructionworkers building the pipeline — since “jurisdiction followsthe worker”)

Retail services or storage of grain/feed for sale that isseparate from the elevator operations (e.g., Cargill meatprocessing, Agricore fertilizer operations)

All trust companies and credit unions (e.g., Canada Trust,Alberta Treasury Branches, Calgary First)

Telecommunications: companies selling cellular phones (e.g.,TAC Mobility)

Production companies that film videos but do notshow/broadcast them

First Nations: industries that do not benefit the band (e.g., acompany that is operated for the benefit of an individualsuch as a retail gas station)

All other types of mining

The following table provides some

guidelines to the regulatory jurisdiction of

federal and provincial industries in Alberta. CrossingsCrossings

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 018

Currently over 160 publications can be ordered through Workplace Health and Safety (WHS),at www.gov.ab.ca/lab/facts/ohs/index.html, or by phoning any of the WHS regional offices (see page 2 for a list of offices). The majority of publications are free of charge; charges mayapply to bulk orders of 20 or more.

Workplace Health and Safety producespublications on a variety of occupationalhealth and safety subjects. Publicationscome as manuals, brochures, booklets,bulletins, posters and stickers, and areregularly reviewed and updated.

New PublicationsFirst Aid Regulation — Questions andAnswers (FA007)• Answers to frequently asked questions

about the new First Aid Regulation.

An Explanation of the First AidRegulation (FA008)• A plain language explanation of the

requirements of the new First AidRegulation. Includes the complete text ofthe regulation.

Fatigue and Safety at the Workplace —Quick Facts (ERG015.1)• A single-page summary of workplace

safety issues involving fatigue.

Noise in the Workplace (HS003)• How to control workplace noise

through a hearing conservationprogram.

Proper Height of Work Surfaces (ERG016)• Advice on proper work surface heights.

Operation of Scott II and IIA Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus inNegative Pressure Mode (BA001)• Advice to employers and workers on the

safe use of this equipment.

Death of a Worker Due to Off-Gassing ofIsobutane Foam Packing Material(CH057)• Recommendations to the trucking

industry after an explosion involvingisobutane.

Worker Killed While Servicing TruckTire (AL019)• Recommendations to the trucking and

tire servicing industries on the safeservicing of truck tires.

Selecting Hand Tools (ERG023)• Suggestions for selecting hand tools

that work well and fit the worker.

Workplace Health and Safety, Alberta Human Resources and Employment

P u b l i c a t i o n s L i s t

Revised PublicationsA Welder’s Guide to the Hazards ofWelding Gases and Fumes (CH032)• Summarizes the dangerous gases and

fumes that welders are exposed to.Includes information on how welderscan protect themselves against thesehazards. Also available as a pocketbooklet.

Safe Work Permits (SH013)• Discussion of work permits that

authorize dangerous or unusual work:what they are and how to use them.

Guideline for Occupational HealthServices (HS002)• Reprint of the International Labour

Organization’s recommendations forthe components of a quality occupa-tional health services program.

The Hazards of Floor Openings (SH012)• Summary of requirements and safe

work practices for safeguardinghazardous floor openings at worksites.

Appropriate Workwear for Flash Fireand Explosion Hazards (PPE005)• Review of the hazards of flash fires

and clothing recommendations forprotection of workers.

Guideline for the Development of aCode of Practice for RespiratoryEquipment (PPE004)• Practical advice and guidance for

those having to prepare a code ofpractice.

Anti-Fatigue Matting (ERG005)• How matting can be used to prevent

soreness and fatigue, including tips onselecting matting.

Don’t Strain Yourself (PH001)• Handy tips for avoiding sprains and

strains when lifting and handlingmaterials. Also available as a pocketbook.

Joint Work Site Health and SafetyCommittee Handbook (LI004)• How to make a work site health and

safety committee work effectively.

C o u r s e s & T r a i n i n g

Canada Labour CodeOne-day information sessions onthe Canada Labour Code Part II andthe Canada Occupational Safety andHealth Regulations from HumanResources Development Canada —Labour Branch.

October 3 Grande Prairie

October 5 Lloydminster

October 12 Edmonton

October 13 Edmonton

October 17 Calgary

October 18 Lethbridge

For more information, or to register, contact Gail:

[email protected] (403) 292-4678 (refer to the

Safety Consultants’ Course)

Focus on Zero Injuries Hazard Alert Training’s falltraining calendar includes thefollowing workshops:

ZERO Injuries – Best PracticesZERO Injuries – Risk AssessmentZERO Injuries – Behavioural Safety OH&S Due DiligenceContractor Due Diligence

For more information, contact:Hazard Alert Training S (780) 466-6960toll-Free: 1-800-561-2319v www.hatscan.com

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 19

Using only one of the many search engines onthe Web, you can enter “musculoskeletalinjuries” and come up with close to 9,000 pages.Ask for “ergonomics” and you find more than61,000 pages. A more specialized search forsomething like RSI (repetitive strain injury)yields a mere 28,000 references. It seems likealmost everybody has something to say aboutwhat was at one time a pretty specializeddiscipline.

Many of these sites are quite useful, whileothers are questionable.

The key is to become a sophisticated surfer.Far too many people think, “If it is on the Web, itmust be accurate.” In its formative days,television was also granted a great deal morecredibility than it deserved. “I saw it ontelevision!” was a common rationale foraccepting some of the most outrageous claimsimaginable. These days, most visually literateviewers take the claims on television with a largegrain of salt.

So how do you tell a good Web site from alikely scam? Simply look at the credibility of thecontent. At the end of the day, remember that ifit seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Some say, “Don’t trust the dot com sites butthe edus, nets, orgs and govs are all fine.” Don’tbelieve it. It is possible to get almost any suffix,simply for the asking. Many unscrupulous peopledeliberately use such techniques to mislead.

Others tend to think that a lot of hits fromthe search engine adds credibility. Give me twodays and I can put up 200 sites for the sameproduct, all from different addresses. And everyone of them will be coming off the sameconnection, the same domain and the samecomputer.

There is a lot of good stuff on the Web. Butyou have to be careful.

Bob Christie is a partner at Christie CommunicationsLtd., a multimedia development company in Edmonton.

W e b W a t c h e r

by Bob Christie

Are You aSophisticated

Surfer?

successfulprosecutions

reporting on recent

under the OccupationalHealth and Safety Act

T h e L a s t R e s o r t

EmployerSahara Sandblasting and Painting Ltd. of Edmonton, Alberta

IncidentOn April 28, 1998, a temporary worker from Active PersonnelServices, 39-year-old Robert Schaff, was fatally injured while hewas working for Sahara Sandblasting and Painting Ltd. Mr. Schaffwas helping a mobile crane operator move a 5.67-tonne heatexchanger vessel from a hi-boy trailer (a high, flat-deck trailerused for hauling heavy equipment or material that can be loadedwith a crane or forklift). The crane was to carry the vessel to anarea for sandblasting and painting. As the crane operatorattempted a 90-degree turn, the crane tipped over and the crane’sboom fell onto Mr. Schaff, killing him.

ViolationSahara Sandblasting and Painting Ltd. was charged with fivecounts of violating the Occupational Health and Safety Act and GeneralSafety Regulation. The company pleaded guilty to one charge underthe Act for failing to ensure the health and safety of the worker.

The investigation determined that Sahara Sandblasting and Painting Ltd.:• failed to ensure the health and safety of all workers engaged in

the employer’s work• failed to ensure that the work was being performed by

competent workers or by workers being directly supervised by a competent worker

• failed to ensure that the crane was operated, used, handled,serviced, maintained and repaired in accordance with themanufacturer’s specifications

• failed to ensure that a competent worker was designated as theoperator of the hoist (crane) and to ensure its safe operation

• failed to address the danger created by the movement of theload being raised and moved, and also failed to provide a tagline (a line or rope tied to a crane load that allows a worker todirect the load but keep enough distance to avoid contact if itfalls)

Penalty$45,000

Full investigation reports are available from the Alberta Human Resources and Employment Library, (780) 427-8533.

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 020

by Ray CisloThe ProblemUsing the wrong hand tool for long hourscan lead to hand, wrist, and arm fatigue andpain.

The SolutionSelect the tool with the grip or handle thatmatches the orientation and height of theworkpiece. Many tools are available inmodels with either in-line or pistol griphandles.

Benefits• Avoids awkward arm positions, reducing

muscular fatigue and potential for hand,wrist, and arm injury.

• The tool can be used with greater controland less force, improving quality andproductivity.

R e a l W o r l d S o l u t i o n s

Choosing the Correct Hand Tool

The ProblemConstant reaching, lifting, supporting and lowering portable hand tools.Highly repetitive tasks can lead to overuse injuries.

The SolutionUse hanging tools for operations repeated at thesame workstation. Many tools can be suspended

from pulleys, counterweights or wire spring coils.

Benefits• Hanging tools are always within reach, and lifting and

lowering motions are eliminated.

• Some of the tool’s weight is always supported,reducing worker fatigue.

• Less storage space is needed and workerproductivity may improve.

Suspending Hand Tools

In the real world, identifying and resolving ergonomic issues requiresawareness, knowledge and a willingness to try new things. Real World

Solutions is a regular column that suggests simple, inexpensive ways toimprove employee health through adjustments to the workplace.

If you've found a solution that you would like to share with our readers,please send it to [email protected]. We will publish those that apply to a broad range of situations.

E r g o t i p s

A Look at HandTool Design

Are your hand tools too heavy or poorlybalanced? Is the grip too large, the

wrong shape or slippery? Poorly designed hand tools can lead

to injuries of the hand, wrist, forearm,shoulder and neck. Choose hand toolsthat save wear and tear on your body.

For example, hammers or pliers withbent handles keep the wrist and forearmstraight, thus reducing injuries andincreasing power. Pliers and cutting toolswith spring-assisted jaws require lessfinger and hand effort to repeatedly openthe jaws. And power tools with foam orrubberized grips help reduce the transferof vibration to the hands and arms.

GripA well-balanced tool with a properlydesigned grip or handle instantly feelscomfortable in the hand. If a tool ispoorly designed or is not right for thejob, you may have to hold it more firmlyand at an awkward angle. A properlydesigned grip helps to reduce fatigue andpain. Consider whether the job requires atool with a pistol grip or an in-line grip.When you have to deliver a lot of poweror torque, select tools that allow a powergrip. With this grip, the hand makes afist with four fingers on one side and thethumb on the other, similar to holdingthe pistol grip of a power drill.

Tools that can be used in eitherhand allow you to alternate hands. They also enable the 10 per cent ofworkers who are left-handed to use them properly.

Give Me

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 0 21

have shown that tools weighing 0.9 to1.75 kg feel “just right” for mostworkers. For precision work where thesmall muscles of the hand support thetool, it should weigh far less. Lighter isbetter. Heavy tools can be made easierto use by suspending or counter-weighting them.

TriggersMany power tools have a trigger that isoperated either by the thumb or oneor more fingers. To avoid hand andforearm fatigue, look for tools thatcan be activated by either hand. Also,the trigger should have a mechanismthat holds or locks it in place whilethe tool is being used. Triggers shouldbe at least 25 mm long for single-finger activation and 50 mm long fortwo-finger activation. Use four-fingeractivation only with suspended tools.

A cautionary note . . .No tools are specifically defined as“ergonomic.” If the tool fits, it’s theright one for the worker and the job.

Ray Cislo, P.Eng., B.Sc. (H.K.), is a safetyengineering specialist at Workplace Healthand Safety.

slipping but can also cut into the handand create pressure ridges, particu-larly if the tool is in continuous use. Ifa grooved handle is your only choice,make sure that the grooves are many,narrow and shallow. If it’s available,try a grip shape that’s non-cylindrical.Triangular grips measuring approxi-mately 110 mm around at their widestpart can be quite comfortable andhelp increase power.

WeightWeight is often a problem with powertools and tools such as axes, hammersand saws. To reduce hand, arm andshoulder fatigue, the hand toolshouldn’t weigh more than 2.3 kg. Ifthe centre of gravity of a heavy tool isfar from the wrist, this maximumweight should be reduced. Studies

Handle sizeThe right-sized handle allows yourhand to go more than halfway aroundthe handle without the thumb andfingers meeting. The recommendedgrip diameter in most cases fallsbetween 50 and 60 mm. To providegood control of the tool and preventpain and pressure hot spots in thepalm of the hand, handles should beat least 120 mm long.

A precision grip (when the tool ispinched between the tips of thethumb and fingers) is primarily usedfor work that requires control ratherthan a lot of force. The handles forprecision tools should be 8 to 13 mmin diameter and at least 100 mm long.

Grip surfacesThe grip surfaces of hand tools shouldbe smooth, non-conductive andslightly compressible to dampenvibration and better distribute handpressure. Avoid tools that have groovesfor your fingers — for most people thegrooves are either too big or toowidely or closely spaced. The resultingpressure ridges across the hand candamage nerves or create hot spots ofpain. Grooves along the length of thehandle are intended to prevent

Poorly designed hand toolscan lead to injuries of thehand, wrist, forearm,shoulder and neck. Choosehand tools that save wearand tear on your body.

a Handa Hand

O C C U P A T I O N A L H E A L T H & S A F E T Y M A G A Z I N E • S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 022

C a l e n d a r

National Health & Safety Conference in CalgaryOctober 24th - 27, 2000Calgary, Alberta

The CSSE (Canadian Society of Safety Engineering) — Albertahosts the Opportunities and Solutions for a New Centuryconference, featuring national, international and provincialspeakers. For more conference information, see www.csse.org.

Best Practices in Ergonomics ConferenceOctober 24, 2000Calgary, Alberta

In conjunction with the CSSE’s national conference, theWorkers’ Compensation Board – Alberta and CSSE showcaseleading-edge ergonomic best practices in the industrial andoffice environments.

For information and a registration form:v www.wcb.ab.ca/html/ergoconf.html S (780) 498-8650

Safe Communities — It’s Everyone’sResponsibilityOctober 26 - 27 2000Peterborough, Ontario