“Nonspecific Abdominal Gas Pattern”- An Interpretation Whose Time is Gone

-

Upload

siddharth-dorairajan -

Category

Documents

-

view

340 -

download

1

description

Transcript of “Nonspecific Abdominal Gas Pattern”- An Interpretation Whose Time is Gone

-

;uest Editoria~

"Nonspecific Abdominal Gas Pattern": An Interpretation Whose Time Is Gone Dean D. L Maglinte, M.D., F.A.C.R. Department of Radiology,/vlethodist Hospital of Indiana, and Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana

S everal reports have addressed the need for radiologists to be clear and pertinent in their interpreta-

tion or reporting of radiologic proce- dures (1-5). Imprecise or poorly under- stood reports can adversely affect the workup and management of patients.

Plain abdominal radiography (PAP,) is one of the more frequently requested examinations in emergency medicine. In our experience, emergency physi- cians frequently utilize the term "non- specific abdominal gas pattern" in their preliminary interpretations when, in fact, they mean that the bowel gas pat- tern is normal (6). A recent survey of community-based teaching hospital ra- diologists showed that 70% of the radi- ologists used this term (7); 65% of these radiologists considered this to be "nor- mal or probably normal," 22% inter- preted this as "cannot tell if normal or abnormal," and 13% defined this term as "abnormal but cannot tell if it is mechanical obstruction or adynamic ileus." Of the referring physicians in the same survey who received the report, 44% defined it as "normal," 51% de- fined it as "normal or abnormal," and 5% defined it as "abnormal, represent- ing either mechanical obstruction or adynamic ileus." Some did not know what the term meant. It is obvious that the term has a wide range of meaning for both radiologists and referring clin- icians. At one extreme, it appears to signify a normal condition; whereas, at the other extreme, it is perceived as a pathologic state such as obstruction. Few other radiologic interpretations

have more consistent disagreement about their meaning both among radi- ologists and between radiologists and referring clinicians.

Prior communications have called for the abandonment of the term "non- specific abdominal gas pattern" (7, 8), and yet the term continues to be used. It is pertinent to consider why this is so. Is it because radiologists and emergency physicians do not read the literature, or is it because a "nonspecific" intestinal gas pattern really exists? My experience suggests that there is a group of patients whose abdominal radiographs do not fit the definition of "normal," "probable small bowel obstruction" and "definite small bowel obstruction" gas patterns. This is likely why there is difficulty in "ignoring" or abandoning this inter- pretation in the absence of an applicable alternative recommendation. How does one report this intestinal gas pattern, and what are its clinical implications?

A recent report of a blinded analysis of plain radiographic abdominal exami- nations in the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction (SBO) by experienced gas- trointestinal radiologists showed a sensi- tivity of 66% (9). This report differed from other studies in that the PAR pat- terns were defined, and a follow-up for every defined interpretive category was given. In this report, 62% of the pa- tients clinically suspected of SBO were, in fact, not obstructed. Of "normal" plain radiographic interpretations, 21% had low-grade SBO. Of the so-called "abnormal but nonspecific" plain radi- ographic interpretations, 13% had low-

grade and 9% had high-grade SBO. The investigators defined the latter pat- tern as borderline or slightly dilated (2.5-3 cm) small bowel with more than two air fluid levels. Of the "probable" SBO plain radiographic interpretations, 37% had low-grade SBO and 16% had high-grade SBO. Of the "definite" SBO interpretations, 26% had low- grade SBO and 23% had high-grade SBO; 13% had complete SBO. This re- port clearly showed that there is a pat- tern which is neither normal nor fits the categories of probably or definitely obstructed. Gammill and Nice (10) rec- ognized this pattern to mean ileus (i.e., the small bowel is unable to push fluid along). Indeed, the word "ileus" means stasis and does not differentiate between mechanical and nonmechanical causes. Our acceptance of the term "ileus" to mean an adynamic etiology when, in fact, it simply means stasis that can re- sult from any cause may be part of the problem.

Plain radiographic examination has remained a mainstay in the evaluation of patients with suspected intestinal ob- struction because of its ready availability, its relative cheapness, and its acceptable clinical record. It is the usual starting point in the radiologist's involvement in the workup of this group of patients. The interpretation "nonspecific ab- dominal gas pattern" should be avoided. I propose the term "mild small bowel sta- sis." If the term "nonspecific abdominal gas pattern" is used, it should be quali- fied as abnormal and should be followed by a specific recommendation for

Emergency Radiology May/June 1996 Guest Editorial 93

-

further workup. This interpretation satis- fies a group of plain radiographic findings that does not fit the normal and definitely abnor- mal categories and has clinical implications (9). Based on the current literature, the various intestinal gas patterns are de- fined as follows:

1. A "normal" intestinal gas pattern is defined as either an absence of small intestinal gas (without abnormal in- crease in abdominal density or loss of soft tissue planes) or the presence of gas within a few (3-4) variably shaped small intestinal loops measuring less than 2.5 cm in diameter. In addition, there is a normal gas and/or fecal distri- bution in a nondistended colon.

2. "Mild small bowel stasis" (abnor- mal but nonspecific pattern) is defined as those cases demonstrating single or multiple loops of borderline or slightly dilated small intestine (2.5-3 cm) with three or more air fluid levels on upright or decubitus radiographs. There is no disproportionate distention of the small

intestine relative to the colon. Gas and/or feces is present in a nondis- tended colon. The term is used to indi- cate an abnormal gas distribution but does not allow distinction between mild reflex or adynamic ileus and me- chanical obstruction. Some of the pa- tients in this category have low-grade obstruction and are difficult to diagnose clinically, and others may have reflex or reactive ileus secondary to a variety of processes, e.g., trauma, critical illness, or urinary tract calculus. Some cases may be related to medication-induced hypoperistalsis and air swallowing (10).

3. A "probable" SBO pattern is de- fined as unequivocally dilated multiple gaseous and/or fluid-fil led loops of small intestine with a moderate amount ofcoionic gas, but the degree of disten- tion of small intestine relative to the colon is insufficient to make a definite diagnosis. Air fluid levels are generally present, but there is an element of un- certainty in diagnosing SBO.

4. A "definite" SBO pattern is de- fined as abnormal and clearly dispropor- tionate gaseous and/or fluid distention of small bowel relative to the colon (or other segments of small intestine). Air fluid levels are evident, and the diagno- sis of SBO is considered unequivocal.

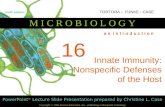

The use of precise definition of plain radiographic intestinal patterns will en- able radiologists to be better under- stood by referring clinicians, allow us to make more cost-effective recommen- dations for further workup in suspected SBO, and prevent misunderstandings with referring clinicians (11). The radi- ologic report should include a recom- mendation for further imaging if this is needed, so that erroneous application of radiologic resources, which can in- crease the cost ofworkup and manage- ment, is avoided. An algorithm is pro- posed for additional imaging in the workup of patients with suspected in- testinal obstruction (Fig. 1). This rec- ommendation is based on the acknowl-

--/g.re

"Normal" or "Abnormal but Nonspecific" and "Probable" SBO Patterns

Acute symptoms Non-acute symptoms esp. ER patient

info~a{ive ::

Clinical Background History, physical and laboratory examinations

Suspected Intestinal Obstruction

i Plain Abdominal Radiography

1

"Definite" SBO Pattern

Surge :al patient

vative ement

Small Bowel + Colonic Distention

Possible colonic Postoperative ileus vs. distal patients or colonic ohst. with signs of

(with incompetent intraabdominal ileocecal valve) inflammation

cT

Figure 1. Algorithm for additional imaging in the workup of patients with suspected intestinal obstruction.

94 Guest Editorial Emergency RadiologT May/June 1996

-

edged limitations of PAR (9), the value of computed tomography in the emer- gent situation (12, 13), and the prob- lem-solving ability of enteroclysis in the subacute or chronic setting (11, 14). It will expedite diagnosis and decrease the cost of workup of the patient with sus- pected intestinal obstruction. The rec- ommendations given are not based on firm scientific evidence but on contin- uing clinical radiologic observations over the last decade (9, 11-17). As the value of other imaging modalities are established, they can be added to the recommendations.

Radiologists must understand each other if we expect other physicians to understand us. The lack of a definition of the meaning of the various terms used in plain radiographic interpreta- tion has resulted in confusion and pre- vented meaningful comparison of dif- ferent reports. It has been estimated that PAl% findings are diagnostic of SBO in about 50-60% of cases; "equivocal" in about 20-30%; and "normal," "non- specific," or "misleading" in 10-20% of cases (18, 19). A careful analysis and clear reporting of the plain radiograph is crucial to prevent erroneous application of imaging resources and clinical mis- management. The "misleading" pat- terns in intestinal obstruction appear to be largely plain radiographic misinter- pretations and miscommunication. Our reports should be concise and as precise as possible.

"Nonspecific abdominal gas pattern" is an interpretation whose time should have been long gone. It serves no useful purpose and deserves permanent burial.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Frederick M. Kelvin, M.D., for his advice and Fran Shaul for secretarial assistance.

:EFERENCE~

1. Olinger NJ, Hunter TB, Hillman BJ. Radiology reporting: attitudes of refer- ring physicians. Radiology 1988;169: 825-6.

2. Fischer HW. Better communication be- tween the referring physician and the ra- diologist [editorial]. Radiology 1983; 146:845.

3. Friedman PF. Radiologic reporting structure [editorial]. AJR Am J Roent- genol 1983;140:171.

4. Revak CS. Dictation of radiologic re- ports [letter]. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1983;141:210.

5. Lafortune M, Breten G, BaudoinJL. Ra- diological report: what is useful for the referring physician? J Can Assoc Radiol 1988;39:140-3.

6. Suh RS, Maglinte DDT, Lavonas EJ, Kelvin FM. Emergency abdominal radi- ography: discrepancies of preliminary and final interpretation and management relevance. Emerg RadioI 1995;2:315-8.

7. Patel NH, Lauber PR. The meaning of a nonspecific abdominal gas pattern. Acad Radiol 1995;2:667-9.

8. Bohrer SP. Nonspecific gas pattern [let- ter]. Radiology 1989;173:283.

9. Shrake PD, Rex DK, Lappas JC, Maglinte DDT. Radiographic evaluation of suspected small bowei obstruction. Am] Gas~roenterol 1991 ;86:175-8.

10. Gammill SL, Nice CM Jr. Air-fluid lev- els: their occurrence in normal patients and their role in the analysis of ileus. Surgery 1972;71:771-80.

11. Maglinte DDT, Herlinger H. Turner WWJr, Kelvin FM. Radiologic manage- ment of small bowel obstruction: a prac- tical approach. Emerg Radiol 1994;1: 138-49.

12. Balthazar EJ. CT ofsmaii-bowel obstruc- tion. AJR Am J Roentgenot 1994;162: 255-61.

13. Tourel PG, Fabre VM, Pradel JA, et aI. Value of CT in diagnosis and manage- ment of patients with suspected acute small-bowel obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;1187-92.

14. Maglinte DDT, Peterson LA, Vahey TN, et al. Enteroclysis in partial small bowel obstruction. Am] Surg 1984;147: 325-9.

15. Megibow AJ, Balthazar EJ, Cho KC, et al. Bowel obstruction: evaluation with CT. Radiology 1991;180:313-8.

16. Maglinte DDT, Gage S, Harmon B, et al. Obstruction of the small intestine: ac- curacy and role of CT in diagnosis. Ra- diology 1993;186:61-4.

17. Gazelle GS, Goldberg MA, Wittenberg J, et al. Efficacy of CT in distinguishing small bowel obstruction from other causes of small bowel dilatation. AJR Am] Roentgenol 1994;162:43-7.

18. Mucha P Jr. Small intestinal obstruction. Surg Clin North Am 1987;67:597-620.

19. Laws HL, Aldrete JS. Small bowel ob- struction: a review of 465 cases. South MedJ 1976;69:733-4.

Emergency Radiology May/June 1996 Guest Editor ial 95