Ngorongoro I: Background · The old Serengeti National Park enclosed approximately 8000 square...

Transcript of Ngorongoro I: Background · The old Serengeti National Park enclosed approximately 8000 square...

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS

NOT FOR PUBLICATION

Ngorongoro I: BackgroundP. O. Box 770Arusha, TanganyikaFebruary 15, 196

Mr. Richard H. NolteInstitute of Current World Affairs366 Madison AvenueNew York 17, New York

Dear Mr. Nolte:

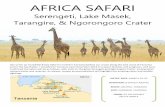

Ngorongoro is unique. Together with the Serengeti NationalPark, it contains the largest herds of migrant .plains game in theworld. In no other place of comparable size can one see such agreat number and variety of wildlife. In a short stay of less thana week, we saw all sorts of game ranging from massive herds of eland,buffalo, and wildebeeste to a few lone rhino and a single cheetah.The sheer weight of numbers makes one feel small and insignificant.

But Ngorongoro is also unique in another way. In a part ofthe world where man is rapidly closing in on the few remaininggzeat herds of wildlife, it is an effort to find a way in whichman and beast can coexist. It is a pioneering attempt to reconcilethe interests of Ngorongoro’s wildlife to those of the pastoralMasai who inhabit the area as well as conservation in general. Forthis purpose Ngorongoro and the surrounding highlands and plainswere excised from the Serengeti National Park in 1959 and recon-stituted as the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (N.C.A.).

Ngorongoro is the crater of an extinct volcano which liesii0 miles due west of Arusha in northern Tanganyika. Geologicallyknown as a caldera, it has a diameter of between ten and twelvemiles and a floor area of 102 square miles, making it one of thelargest in the world. The average height of the rim is about2,000 feet above the floor of the crater, and it is surrounded byvolcanic highlands with six peaks rising to more than i0,000 feet.The hot and dusty lowlands are largely to the north and west of thecrater and merge gradually with the Serengeti Plains. Most of thewater rising in the Area drains either into one of the severalcraters or else disappears into the drainless Rift Valley. A fewof the streams in the north-west, however, run into Lake Victoriaand thence down the Nile to the Mediterranean.

We drove to Ngoronggro fromArusha (see map on page 2). Theroad first goes south to a smallsettlement known as Makuyuni,then west across the hot RiftValley to a village appropriatelycalled Mto wa Mbu, Mosquito Creek.Then it winds 700 feet up theprecipitous western escarpmentof the Rift to emerge on a cool

Bat-eared Fox (Otocyon megalotis)

NATIONALPARK

vl SERONERA TOrER 97 MILES

r,.FROM LOLIONDO TO

112 MILES

OLDUW41

HIFTING

OLMOT! CRATER

LEMAGRUT MT. ONGORCIO276’ CRATER

EN DU E N CON ERVA,TH.Q.

KERIMASI MT.

LOOILMALASIN M1969’

OLOSIRWA MT. /7"00’

//

I/

OLDEANI MT.IO4.60’

KAKESIO

SCALE lINCH IO MILES

MTO WA MBUFROM ARUSHA TO

CRATER IIO MILES

(APPROX.

...Ngoro..ngI0ro Consgryation Area

plateau with breathtaking views o Lake Manyara National Parkand its soda lake below. On a clear day one can also make outthe forested slopes of Ngorongoro rising on the horizon. Aftera further hour’s drive over gently rolling country, one arrivesat the lodge on the crater rim. Here at ,500 feet. the air isclear and fresh. While pleasantly warm during the day, itbecomes quite crisp the moment the sun sets.

From the lodge one can easily watch the great herds oanimals below. Occasionally one can make out a herd of Masaicattle, as well as the primitive Masai bomas where they liveand herd their cattle at night. AcrosS-’@ floor of the crater

IMW-3g -3-

to the north lie the smaller craters of O1 Moti and Embagai.Next to them, Loolmalasin, the highest peak in the Crater High-lands, dominates the countryside. Scenically it is most spec-tacular country.

The area around Ngorongoro has long been inhabited by man.Nearby Olduvai Gorge is the richest and most important archeo-logical site in East Africa, and it was here in 1959 that Dr.Louis Leakey found the remains of Zinjanthr0pus, an Australo-pithecine "near-man". In the following year he found fragmentsof a skull of a slightly older being, believed to be the earliesttoolmaker so far known and therefore by definition the first man.This early hominid is thought to have lived nearly two millionyears ago. Since then there is evidence of fairly continuousoccupation up to this day. The present inhsbitants, the Nilo-Hamitic Masai, however, ame relative newcomers and arrived onlyduring the first half of the last century.

The first European to lay eyes on Ngorongoro was Dr. OscarBaumann, a German, who on March 18, 1892 recorded in his diamy:"At noon we suddenly found ourselves on the rim of a sheer cliffand looked down into the oblong bowl of Ngorongoro, the remainsof an old crater. Its bottom was grassland, alive with a greatnumber of game; the western part was occupied by a small lake."Decending into the crater, Baumann promptly disposed of "onewildebeeste and three rhino; the latter we left to the Masai."Presumably the wildebeeste was for his own larder, but the rhinowere undoubtedly dispatched for pmofit, although he and none ofthe early explorers admitted it. In those days, as today, rhinohorn commanded a highprice at the coastwhence it was exportedto India and the FarEast for medicinalpurposes ranging froman aphrodisiac inIndonesia (a fallaciousbelief) to a generalhealth tonic in Indiaand a fever reducer inChina.

During the Gemmancolonial period, theGovernment tried to ex-clude the Masai fromthe area, although inthis they were notentirely successful.This policy, however,permitted the aliena-tion of much of thecrater floor to thebrothers Siedentop Masai Moran

who surely must have owned one of the most unusual farms in whatwas then German East. The rest of the area was largely unadmini-stered, although it had been thoroughly explored and well mapped.

When the British took over after the irst World War, certainMasai sub-tribes were encouraged to return. Siedentop’s arm wassold by the Custodian of Enemy Property, but since the purchaserailed to uiili the necessary development conditions, it eventu-ally reverted to the Government in 198.

During the early years of the British administration theirst hesitant steps toward conservation were taken, and by 1928the Ngorongoro Crater area had been given a high degree o pro-tection. This was gradually increased, and in 190 the westernSerengeti and the Ngorongoro game reserves were merged to form theSerengeti National Park. The Second World War intervened, and asthe attention of the Government was absorbed by other issues, therewas little actual change in the administration o the area. Aterthe war when the National Parks organization was established and atlast took over, the local Masai had no idea that their rights to thearea, although safeguarded, had been limited by legislation. Theconflict between the exercise o these rights and the interests oconservation were to beset the area with difficulties from the verybeginning.

Gradually the Parks organization csme to the conclusion thatthe continued presence o the Masai and their stock within theboundaries o the Park was irreconcilable with its purpose. Theythus approached the Provincial Administration and together workedout a proposal to establish a park free rom human habitation overthe three most important game areas" the western Serengeti, Ngoron-goro Crater, and Embagai Crater. The remaining parts would becomea conservation area where human interests would be allowed although

game would be pro-

The pubiication

iiiiiii!!iiii!iiill il ii iil ii i of these proposals asa Government WhitePaper led to a tre-

England and America.The Fauna PreservationSociety commissionedProfessor Pearsall ofLondon University tomake an ecologicalexamination of the

Lake Manyara fromthe top of the RiftEscarpment.

IMW-34

Zebra with foal.

the area. His report,published in 1957,noted that increasedcompetition betweenthe game and the Masaiin the area was inevi-table. "Hence theyshould ultimatelyoccupy separate terri-tories, each suitablefor their somewhatdifferent needs."

In an effort tosolve the problemequitably, the Govern-ment appointed a Com-mittee of Enquiry in1957. Their recommend-ations included thatthe Masai should be keptout of the western Serengeti completely; that the Crater Highlandsshould constitute a special conservation unit, to be administereddirectly by Government, where the Masai would be allowed to continuetheir traditional mode of life under minimum safeguards and conditions;and that the Ngorongoro and Embagai Craters should have a specialstatus as nature reserves where no human habitation would be allowed.

In order to find a solution which might "after the uncer-tainty of recent years, be simple, clear and final", the Govern-ment accepted most of the Committee’s recommendations. It modifiedthem, however, in two important ways: l) it did not accept theproposal to create special nature reserves in the Ngorongoro andEmbagai Craters, although it did recognize they would be "a specialconcern of the team responsibility for the adiministration of theConservation Unit"; and 2) it extended the proposed conservationarea to include not only the Crater Highlands but the whole of theNgorongoro Division of Masai District.

In terms of area there was a sizable redistribution of land.The old Serengeti National Park enclosed approximately 8000 squaremiles, 3000 of which were excised to form the N.C.A. Neverthelessa further 3000 were added to the new park bringing its area back to8000 square miles. In other words there is more land under someform Of protection now than there was before 1959.

On July l, 1959 the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Ordinancecame into effect. It charged the administration with "the conser-vation and development of the natural resources of the ConservationArea". Shortly afterwards the situation was explained to the Masaiby the Governor when he addressed their Federal Council on August27, 1959:

IMW-3

From the Crater rim.

Another matter whichclosely concerns the Masaiis the new scheme for theprotection of the NgorongoroCrater. I should like tomake it clear to you allthat it is the intentionof the Government to developthe Crater in the interestsof the people who use it.At the same time the Govern-ment intends to protectthe game animals of thearea; but should there beany conflict between theinterests of the game andthe human inhabitants,those of the latter musttake precedence. TheGovernment is ready to

start work on increasing the waters and improving the grazingranges of the Crater and the country around it; for yourpart you must take care to fulfill the agreements intowhich you have entered to keep the countryside in good heart.You must not destroy the forests, nor may you graze yourcattle in areas which have been closed under any controlledgrazing scheme; at the same time you must be certain tofollow veterinary instructions designed to pz’event disease.

The first years of the N.C.A. represented years of trial anderror during which the adqinistration attempted to find the mostsuitable way to carry out its unique mandate. Throughout, the N.C.A.has remained supreme in matters dealing with land management, naturalresources, and conservation. In more detail, the administration’ sduties include the development of better grazing with greater carry-ing capacity, efficient range management, the provision of addition-al water points, the protection of the forests and water catchnentareas, and the potection of wild life. Social services, police,and the law, however, have remained integrated with the MasaiDistrict of which Ngorongoro is a part.

In September 1961 the Minister for Lands, Forests and Wild-life appointed a full-time Conservator responsible directly to him.Henry Fosbrooke, the Conservator, was once district officer atNgorongoro as well as Senioz" Government Sociologist. The purposebehind making him directly responsible to the Minister is thatthere should be national control of a national asset, much in thesame way as the U.S. National Park Service. Furthermore, nationalpoliticians are not as sensitive to local pressures as local"politicians and so can hshte keep the interests of conservationuppermost.

The key to the Conservation Area is the i0,000 Masai who

who live there. Any effort to conserve and develop its naturalresources must take into consideration their traditional way oflife since, subject to certain conditions, they have clearlydefined rights in the Area. These they guard jealousy, largelybecause of a feeling of insecurity. As Henry Fosbrooke pointsout, this has its roots deep in the past. Since the Europeanconquest of East Africa, the Masai have steadily lost land, inKenya and Tanganyika, to white settlers as well as Africans. Forobvious reasons this land tended to be their best; land with suffi-cient water to which they could retreat with their cattle in dryperiods. This has resulted in overcrowding on the remaining areas,leading to erosion, pasture deterioration, and famine during droughts.Thus every suggestion concerning land is regarded, and not withoutreason, with the utmost suspicion. The asai of Ngorongoro aredetermined to maintain their rights to the Area, even if it involvessuch things as the apparently senseless effort of trekking theircattle into the Crater every day for water rather than availingthemselves of a piped water supply at the rim specially built fortheir convenience. "This is a trick" was their response "to getus out o the Crater."

Nevertheless, some of the more advanced Masai are beginningto realize not only that their present wasteful practices aredestroying the habitat, but also that wildlie is a resource ogreat potential. Because o rainfall, soil, and topographiclimitations, the most eicient use o much o Masailand lies inorage or livestock and game. There is much evidence that acertain degree o symbiosis between the two is beneicial. os-brooke again points out that although pure pastoralism has ageneral effect of degradation of the environment, pastoralistsare not usually hunters since they do not have a protein defic-iency. On the otherhand there is a closerelationship betweenagriculture and poach-ing. Indeed the greatgame concentrations inEast Africa exist inareas inhabited eitherby pastoralists or bythe tsetse fly.

Luckily for goron-goro, the Masai arepastoralists, distainingagricultural work of anykind. On the other handthey have allowed agri-culturists to settle ontheir land. With ampleprotein available from

Jackal

IMW-3 -8-

their own herds, they do not eat game mea$, nor do they poach,and some of the greatest of African game parks are within Masai-land’s borders, such as Amboseli, Serengeti, and Ngorongoro.Where the Masai have lost land, the great herds of wildlife havedisappeared too. The Masai attitude is exceptional among Africantribes, who in Swahili refer to wild animals as n, meat, muchas we refer to them as "game" They seem interese in preservingthese animals, and if properl} managed there need be only theminimum conflict between man and wildlife. This is ust what theNgorongoro Conservation Area hopes to accomplish, but first of allthe Masai employ certain techniques which are harmful to theenvironment and which must be controlled before development cantake place. These are cultural patterns, however, and are notamenable to administrative decrees.

A nomadic people, the Masai are attracted to Ngorongoro (one-fifth of all Tanganyika Masai and their cattle live within the N.C.A.)because of its assured water supply during the dry seasons. Theyherd their cattle to the Crater Highlands when the dry grazingbecomes sparse, only 9o return immediately at the onset of the rains.This is injurious to the pasture, however, for the plains grassesare flogged before they have a chance to grow, while the highlandgrasses are neglected so that the coarser species mature and becomeinedible before grazing takes place. In other words the plains areovergrazed, while at the same time the highland pastures are deteri-orating because they are not utilized sufficiently.

At the same time the large size of some Masai herds areobviously excessive and greater than the land can carry, for theMasai value quantity over quality and pay little attention to thecarrying capacity of the land. The catastrophic drought of 1960-61reduced some herds by as much as 90% (only 19% at Ngorongoro), butthey can recuperate all too quickly in a series of good years, eat-

ing everything in sightand exposing the top-soil to erosion. Manyof the 1961 ArushaConference members (seeI4-6) who visitedNgorongoro left con-vinced it was a vastdust-bowl. Its richvolcanic soil hasincredible recupera-tive powers, however,and it was lush andgreen during our visit.

The destructionof the environment is

Thompson’s Gazelle

Iiw-3 -9-

White-bearded wildebeestor gnu.

another crucial problem inMasailand as a whole.Uncontrolled and wide-spread fires have beenparticularly harmful inthe Ngorongoro Area.Besides producing freshpasture, the Masai burnthe grassland because itrids the ground of dis-ease-beaing ticks. Butit also leads to erosionand the encroachment ofcoarse tufted grasses.Furthermore, uncontrolledfires gradually invadethe forests destroyingor seriously harmingessential catchment basins. In general the destruction of theenvironment can be far more harmful to the existence of wildlifethan a direct attact by hunting and poaching.

In orde to coordinate the objectives of the N.C.A. aManagement Plan was drawn up in 1960 and later revised in 1962.It asserted that Ngorongoro is an asset both of national importanceand international significance:

A basic requisite for the Area is a stable environ-ment in which its human and animal inhabitants, includinglivestock, can prosper. Such stability of environmentis essential for the achievement of the long-temobjective, namely the conservation and rationaldevelopment of the natural esources of the Areawhich embrace in addition to water, soil, floraand fauna, those other equally valuable but lesstangible resources contributing to amenity andrecreation. Only if all these resources are inbalance will it be possible to maintain the rightsof the existing residents, preserve unscathed thescenic attraction, safeguard te wildlife, per-petuate the value of the area for research, andso ensure that both the national and internationalobligations are honored. Management of the Areamust be directed at meeting these diverse require-ments in full, and this is the management task laidon those responsible.

Since it is inherent in a stable environmentthat there shall be no permanent deterioration ofthe habitat, the uncontrolled increase within theArea of human beings, domestic stock and wild

animals cannot be allowed.

IMW-3 -iO-

Frozen with fear, theAfrican hare blends inwith his surroundings.

This documentincludes all kinds ofinformation and materialrelating to Ngorongorowhich had not beengathered together before.With chapters on history,agriculture, forestry,game, and land use, itprovides an integratedplan for the develop-ment of the Area andis presently beingused as a basis foroperations.

In my next news-letter I shall describe some of the day to day problems of runningthe N.C.A. and their implications for the future.

Very sincerely yours,

lan Michael Wright

Opposite: Lion. The black spot in the middle of the nearestlion’s back is a swarm of st_omoxys flies (see IMW-35).

Page 12 Rhino.

The line drawing of bat-eared foxes on page one is reproduced bycourtesy of iiss Ruth Yudelowitz. The map on page two isreproduced by courtesy of the Conservator, Ngorongoro Con-servation Area.

Received in New York February 27, 1964.