Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

-

Upload

aadesh-singh -

Category

Documents

-

view

225 -

download

0

Transcript of Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

1/86

Natural Rights

Rights

The Declaration of Independence claimsthat

men have certain rights. This ideaof rights is

clearly one of the basic ideasof the philosop

hy of natural rights. WeAmericans often arg

ue about whatrights there are. Is there, for

example, aright to die? We also argue about

whohas certain rights. Does the fetus in the

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

2/86

womb have a right to life? However,despite th

ese differences, we tend totake the idea of rights f

or granted. Werarely stop to ask just what a right

is orwhat it is for a person to have a right.Now, in

fact, contemporary philosophyrecognizes several

different kinds ofrights. We will consider some of t

hesedifferent kinds of rights in laterchapters of thi

s book. Here, though, wewill focus on a particular

conception ofrights that is central to the philosop

hyof the Declaration and to the historicalcore of th

e philosophy of natural rights.

According to this conception, a right is amor

al claim belonging to an individualthat prohi

bits all other persons fromacting in certain

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

3/86

ways toward thatindividual. For example, you

r right tolife prohibits all other persons fromkilling

you. Similarly, your right toliberty prohibits all oth

er persons fromenslaving you, kidnapping you, or

holding you prisoner against your will.Such rights

are often said to be moralfences: They surround

people andprotect them from outside interf

erence.They are said to be "negative rights"

inthat they stipulate things that otherpeopl

e may not do in their interactionswith some i

ndividual. Your right to lifesays that I may not kil

l you. My right toliberty says that you may not en

slaveme.

Rights protect people from outsideinterference. B

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

4/86

ut, of course, theprotection afforded by rights is n

otalways effective. People have beenmurdered. Pe

ople have been enslaved.The natural-rights theory

does not denythese unfortunate facts of life. Wha

t itdoes say is that murder and slavery areserious

moral infractions. This is whatis meant by saying t

hat rights are moralclaims or moral fences. They s

tipulatethings that other people should not doto y

ou. They specify limits on how wemay rightly or j

ustly interact with oneanother. They also provide t

he basis forcomplaints of unjust treatment, aswhe

n the American colonists in theDeclaration of Inde

pendence pointed toa series of actions by the king

ofEngland as transgressions of theirrights, transg

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

5/86

ressions that justifiedresistance to English rule.

Natural Rights

The rights to life and liberty claimed bythe Declara

tion prohibit people fromkilling or enslaving one a

nother. In thisrespect these rights are like rightscr

eated by human beings. Human lawsoften prohibit

certain kinds of actions.Murder and kidnapping ar

e illegal.Human law forbids them, though ofcourse

this does not prevent theirhappening from time t

o time. Like therights proclaimed in the Declaratio

n,legal rights say how we should behave,which is

not always how we do behave.Legal rights, like th

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

6/86

e rights of theDeclaration, are prescriptive, notdes

criptive. Both prescribe certainbehaviors. But sinc

e we humanssometimes fail to live up to thesepre

scriptions, neither accurately describes how we in

variably will behave.In these ways the rights claim

ed by thephilosophy of natural rights are likelegal

rights. Nonetheless, there aresome important diff

erences. Thesedifferences are central to the idea

ofcertain rights as natural rights.

The fundamental difference betweennatural

rights and legal rights is thatlegal rights are

created by humanbeings and natural rights

are not.Human law may give me certain righ

ts .For example, human law gives me theright to d

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

7/86

rive a car provided I meetcertain requirements. S

upposing I havemet those requirements, no one

mayinterfere with me in the lawful drivingof my ca

r. However, the legislaturemight decide to restrict

nighttimedriving for people with poor nightvision,

or it might, because of life-threatening problems o

f pollution,decide to ban automobile driving for all

but emergency purposes. My right todrive a car is

created by human law andmay be modified or ab

olished by theaction of a legislature composed ofh

uman beings. My natural rights arenot like this.

Consider, for example, my natural rightto life, a ri

ght I have independent of anyhuman action. The

Declaration saysthat I am endowed with this right

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

8/86

by mycreator. It belongs to me simply invirtue of

my being a human being who,like all human being

s, is created equallywith a certain nature. It belon

gs to meby nature, not by human artifice. Mynat

ural right to life does not dependupon any h

uman act of creation andcannot be taken aw

ay by any humanaction. Legal rights are create

d byhuman action and can be taken away byhuma

n action. An evil legislative bodymight pass a law

denying me a legalright to life. The legislature mig

ht,correctly following the rules ofparliamentary pr

ocedure, amend thehuman law to permit the killin

g ofhuman beings of a certain kind.

Something like this happened inGermany in

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

9/86

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

10/86

The idea of a natural right to life can beeasily gras

ped by reflectingon the debate over abortion that

hasdivided Americans for the last quartercentury.

On one side, the statelegislatures and the courts

have saidthat abortion, subject to somerestriction

s, is legal. The law does notrecognize a fetal right

to life. On theother side, opponents of abortion ar

guethat abortion is a great moral evilbecause it in

volves the violation of anatural right to life that bel

ongs to everyhuman fetus. Now, not all natural-ri

ghts theorists would agree that humanfetuses do

have a natural right to life.Here there is important

disagreementabout who is included among the cla

ssof beings that have a right to life. However, thi

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

11/86

nking about the abortioncontroversy can hel

p us see what isinvolved in claiming such a r

ight. Thefetal right to life is supposed to be

anatural right. Such rights do not dependup

on human creation, and while theymay be vi

olated, they ca nnot bedestroyed by any human

action.

Natural Law

We have already seen that naturalrights are

in some ways like legal rights.Both prohibit

other people frominterfering with us in certa

in ways.Both involve a complex network ofr

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

12/86

esponsibilities corresponding to therights th

ey claim. My natural right tolife imposes a duty o

n you and allothers to refrain from killing me. Myri

ght to drive a car imposes a duty onyou and all ot

hers to refrain frominterfering with my lawful exer

cise ofthat right. Legal rights exist as part of asyst

em of laws. My legal right to drive acar and the co

rresponding duties ofother persons are precisely s

pelled outby the laws governing the use of motorv

ehicles. In a similar way, natural-rights theorists c

onceive of naturalrights as existing within a syste

m ofnatural laws. The Declaration ofIndepend

ence itself mentions "the lawsof nature and

nature's god" as the basisfor those rights to

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

13/86

life, liberty, and thepursuit of happiness it g

oes on to claim.

These laws of nature are moral laws.They ar

e not like the laws of naturediscovered by p

hysics and chemistry,which tell us how thin

gs invariably doact but say nothing about ho

w things should act. Unlike the laws of chemistr

yand physics, but like human-

createdlegal laws, moral laws of nature areprescri

ptive rather than descriptive.They tell us how we

ought to behave,not how we invariably do behave

.

Like many, natural-

rights theorists, theauthors of the Declaration ofIn

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

14/86

dependence saw the laws of nature asGod's laws.

The Declaration

conceives of natural rights as part of alarger syste

m of natural law, a body ofmoral law coming from

God rather thanfrom any human legislators. It isi

mportant, however, to distinguish this"natural law

" from what philosophersand theologians have tra

ditionallycalled "revealed law." The biblical textkno

wn as the Ten Commandmentsserves as an excell

ent example ofrevealed law. According to the bibli

calstory, these commandments were givendirectly

to Moses by God in anencounter on the top of Mo

unt Sinai. Inthis story God reveals thecommandm

ents of the moral law toMoses and through him to

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

15/86

all of God'schosen people. Preserved in the holys

criptures of the Jews, Christians, andMoslems, th

ese commandments arethen revealed to all who r

ead them. Theappearance of God before Moses o

nMount Sinai is an example of a specialrevelation,

an instance of God'sspeaking to a particular indivi

dual orgroup of individuals at a particularpoint in ti

me. The revelation of God'smessage in the scriptu

res, available toall who can read them or hear the

mread, is an example of generalrevelation. Reveal

ed law is based uponthe general or special revelati

ons ofGod's commandments that haveappeared in

the course of humanhistory. In revealed law God'

s moral lawappears to humans in the form ofcom

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

16/86

mandments given by a divinelawgiver.

While philosophers and theologianshave gen

erally agreed that the contentof revealed la

w and the content ofnatural law are the sam

e, the idea ofnatural law includes within it t

he ideathat the moral law can be known by t

heuse of human reason unassisted byeither

special or general revelation. Forthis reason

natural-law philosophershave often spoken

of natural law as thelaw of reason. Natural la

w is a system ofmoral laws that human beings ca

n cometo know by observing the nature ofthings

and thereby discovering the rightuse of those thin

gs.

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

17/86

An example may help make this clear. Itis of the n

ature of something that is aknife to have a sharp

edge. Without asharp edge suitable for cutting, a t

hingwould not be a knife. Now, it is possibleto use

a knife in many different ways. Itcould be used to

pry nails or as adoorstop, for example, but such

useswould tend to damage the blade of theknife.

For this reason they might besaid to be contrary t

o the nature of theknife. Such uses are not the us

es forwhich the nature of the knife is suited.On th

e other hand, to use the knife forcutting is to use i

t in accordance with itsnature. The general idea

of natural-lawtheory is that the right use of

a thing isthe use that is in accordancewith it

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

18/86

s nature and that any use of athing that is c

ontrary to the nature ofthe thing is a wrong

use of the thing .

Now, in this example there is surely nogreat mora

l wrong in using a knife topry nails. But the examp

le should helpus see how important moral laws mi

ghtbe discoverable by examining thenatures of thi

ngs. Consider, forexample, the nature of human b

eings.We are animals, and in this respect ournatu

re shares some features with otheranimals. But h

uman beings also have acapacity for thinking abo

ut what theyare doing. Unless forced to change b

ychanges in their environments, otheranimals repl

icate the ways of life oftheir ancestors. Humans,

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

19/86

on the otherhand, are constantly changing t

heirways of life. They think about their way

of life and try to find better ways tosatisfy t

heir needs and better ways toexpress their t

houghts and feelings. It isthis capacity to thi

nk about what theyare doing, to reflect upo

n their way oflife, and to guide their lives by

theirthoughts that many philosophers have

considered to be one of the distinctivefeatur

es of human nature. Humanbeings are anim

als, but they are rationalanimals. Every norm

al human beinghas this capacity for thinking about

hisor her life and guiding that life by thisthinking.

This is a capacity that appearsto be unique to hu

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

20/86

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

21/86

g. While itmight be possible for a human being toli

ve his or her life without ever stoppingto think ab

out it, such a life would failto correspond to huma

n nature. Even ifit produced a life of success and

greathappiness, such a life would be, in somesens

e, subhuman. It would not be a lifein accordance

with our human nature.For this reason the philoso

pher Platosaid in his Apology that "theunexamined

life is not worth living forman."

Consider also the implications of thisway of thinki

ng about human nature forthe institution of slaver

y. Suppose againthat it is true that every normal h

umanbeing has a capacity for thinking abouthis or

herlife and guiding that life by his or herown think

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

22/86

ing. When we enslave humanbeings, we make the

m the subject of ourwill. We tell them what to do.

In doingthis we treat them as mere animals,lackin

g the power of rational self-direction. But, in doin

g this, we treathuman beings contrary to their nat

ureas human beings. In this way thenatural-law t

hinker can argue thatslavery is contrary to the law

of nature.In this way also we can see how thenat

ural right to liberty can beunderstood as a require

ment of thenatural law. Every normal human bein

ghas a capacity for rational self-direction . Conseq

uently it is contrary tonatural law to deprive

a human being ofthe opportunity to exercis

e thatcapacity. We have a duty to refrain fro

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

23/86

msuch violations of the natural liberty ofa p

erson, and this, of course, is justwhat is mea

nt in saying that a personhas a natural right

to liberty.

Natural Equality

We are now in a position to understandone o

f the most puzzling phrases in theDeclaratio

n of Independence. TheDeclaration says tha

t "all men arecreated equal." But this seems

to bepatently untrue. Some men are wise;ot

hers are not. Some men are strong;others are w

eak. Isn't it obvious thathuman beings are very dif

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

24/86

ferent fromone another in these and otherrespect

s? How can the Declaration saynot just that all me

n are equal but thatthis equality is self-evident? O

necommon response here is to say that allthe Dec

laration means in saying that allmen are created e

qual is that all menhave equal rights. But this resp

onsemakes obscure the Declaration's twoseparate

claims: one that all men arecreated equal and an

other that all menhave certain rights. Further, this

response misses entirely the connectionbetween t

hese two claims, theconnection between human n

ature andnatural rights discussed above. Thisconn

ection is central to the whole ideaof natural law.

In considering the idea of natural law,we saw how

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

25/86

the right use of a thing issupposed to be connect

ed to the natureof the thing. According to this vie

w,slavery is wrong because it involvestreating a h

uman being with a capacityfor rational self-directi

on in the waythat one would treat an animal thatla

cked this capacity. In this view, theright to liberty

that slavery violates is anatural right inherent in th

e very natureof a human being as a rational anima

l.It is this conception that lies behind thewords of

the Declaration. All men arecreated equal in the s

ense that all menhave the capacity for rational self

-direction, and

it is because all men have this capacitythat all hav

e the equal right to liberty. This connection bet

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

26/86

ween an equality ofrights and a prior equalit

y of natureupon which the equality of rights

depends is clearly formulated by Lockein the Sec

ond Treatise , where he saysthat there is "nothin

g more evident thanthat Creatures of the sa

me species andrank promiscuously born to a

ll thesame advantages of Nature, and the us

eof the same faculties, should also beequal o

ne amongst another withoutSubordination o

r Subjection."

Thesame idea, that an equality of rights isbased u

pon a prior equality of nature, isalso clearly prese

nt in the draft of theDeclaration of Independence

written byThomas Jefferson. There the keyphiloso

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

27/86

phical section reads as follows:

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all m

en are createdequal & independent, that fromthat

equal creation they deriverights inherent & inalien

able,among which are thepreservation of life, & lib

erty &the pursuit of happiness.

The equality of men is an equality ofkind. All

men are equal in the sense thatthey are all

members of one kind and assuch share in th

e nature of that kind .Because a capacity for rati

onal self-direction is part of our nature as humanb

eings, natural law requires that we betreated in ac

cordance with that nature.Our natural right to libe

rty is thus aconsequence of a distinct equality ofn

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

28/86

ature, an equality of kind.

Inalienable Rights

Inalienable rights are often thought tobe rig

hts that cannot be taken from us.A more acc

urate view would be thatinalienable rights a

re rights that wemay not relinquish . In the le

galterminology of the eighteenth century,to aliena

te a thing was to transfer one'srights over it to so

me other person. Tohave property rights in a thin

g was tohave the exclusive rights to use, sell,beq

ueath, or destroy the thing. Some orall of these ri

ghts could be transferredto another person. Thus

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

29/86

the rights ofownership over a horse might bealien

ated by selling the horse or givingit away. While in

those days laws ofentailment restricted the transf

er ofsome landed property, theserestrictions were

created by human lawand applied only with respe

ct to someproperty. For the most part, propertyot

her than land could be alienated by itsowner at wil

l. Alienation of one's rightsover a horse involves t

healienation of legal rights of ownership,rights tha

t are created by human laws.While many interesti

ng moral problemsmay arise in considering the rig

htnessor wrongness of specific transfers ofpropert

y rights, there seems to be nofundamental difficul

ty in the idea of thealienability of such rights. But

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

30/86

when wecome to our natural rights, there doesse

em to be a fundamental difficulty.

Consider my natural right to liberty.May I alienate

this right? May I give upthis right and transfer it to

some otherperson? May I sell myself into slavery

?If I do so, am I not treating myselfcontrary to m

y nature? The law ofnature is based on the nature

of things.Partaking of the nature of human kind,I

share the capacity of rational self-direction. Accor

ding to the natural law,I have a moral obligation t

o live inconformity to this nature. I have amoral o

bligation to use my capacity forrational self-directi

on. If I sell myselfinto slavery, I fail to live up to t

herequirements of the law of nature. Forthis reaso

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

31/86

n, I may not alienate my rightto liberty. Unlike the

property rights Ihold in a horse, my right to libert

y is aninalienable right. By similar reasoning,it wo

uld seem that all my natural rightsare inalienable.

Since I have thoserights in virtue of my God-given

nature,I, like everyone else, am obliged by thela

w of nature to respect those rights inmyself. Thus

the Declaration ofIndependence holds that when

a peopleconfronts a despotic attempt to ruleover t

hem, "it is their right, it is theirduty, to throw off s

uch Government."

Self-Evident Rights

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

32/86

The Declaration of Independence holdsthat it is "s

elf-evident" that all men arecreated equal and that

they areendowed by their creator with certaininali

enable rights. With this idea of"self-evident" truth

s we encounter oneof the more esoteric aspects o

f thephilosophy of natural rights embeddedin the

Declaration. We can begin to seewhat is involved i

n the idea of self-evidence by considering system

s suchas the geometry developed by theancient G

reek astronomer Euclid. InEuclid's system a certai

n theorem ofgeometry is proven to be true bysho

wing that it follows necessarily fromtheorems that

have already been provento be true. If we ask ho

w we know thatthese earlier theorems are true, th

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

33/86

eanswer is that they follow from othertheorems th

at already have been provento be true. In this wa

y the truth of eachtheorem can be shown to follo

w fromwhat has already been proven to

be true. But it is obvious that suchreliance upon p

rior results cannot becontinued indefinitely. The w

holesystem must begin somewhere. In thegeomet

ry of Euclid it begins withcertain axioms. These ax

ioms state thefundamental principles from which t

hetruth of all other theorems areultimately derived

. But how can weknow that these axioms are true

? If weappeal to some other principles asevidence

for the truth of our axioms, wemerely postpone t

he difficulty, sincenow the question arises as to h

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

34/86

ow weknow that these other principles aretrue.

fOne way of solving this difficulty, ofbringing the d

emand for justification toan end, is to say that the

se axioms areself-evident. What is meant by this i

sthat anyone who truly understandswhat an axio

m is saying will see that itsimply must be true. It r

equires noevidence outside itself to support it. Itst

ruth is manifest in itself. Consider, forexample, th

e principle that equalsadded to equals give equals

. The truthof this principle is transparent toanyone

who understands what it says.It needs no proof,

no external evidence.It is self-evident. Its truth is

so clearand certain that no additional evidencecou

ld make it more evident to us than italready is.

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

35/86

Like many other philosophers, JohnLocke believed

that in principle it waspossible to construct a syst

em of ethicsthat, like the mathematics of Euclid,w

ould begin with self-evident axiomsand derive fro

m them a completeaccount of the principles of mo

rality.He described the knowledge of suchself-evid

ent truths as being "like brightsunshine" that "forc

es itselfimmediately to be perceived, as soon asev

er the mind turns its view that way;and leaves no

room for hesitation,doubt, or examination, but th

e mind ispresently filled with the clear light ofit."

Despite his repeated assurancesthat such a proje

ct was in principlepossible, that the laws of nature

couldbe known by the methods of geometry,Lock

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

36/86

e himself never provided us withanything like a de

ductive system ofethics. Nonetheless, we have alr

eadyconsidered some comments he made inthe S

econd Treatise that throw somelight on the claim t

o self-evident truthfound in the Declaration ofInde

pendence.

Recall that in the Second Treatise Lockeclaimed th

at there was "nothing moreevident" than that crea

tures of the samespecies "should also be equal on

eamongst another without subordinationof subjec

tion." In the section thatimmediately follows this r

emark, Lockegoes on to cite the similar view ofRic

hard Hooker, another philosopher ofthe natural la

w, that it is "evident in itself" that the equality of

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

37/86

men by natureis the foundation of our moralobliga

tions to one another. In

effect Locke and, in Locke's view,Hooker are sayin

g that it is self-evidentthat men are equal by natur

e and self-evident that because men are equal by

nature they have equal rights. Thesetwo claims ab

out self-evident principlesare the same two claims

made byJefferson in the rough draft of theDeclar

ation, where he held that it wasself-evident that "

all men are createdequal & independent" and self-

evidentthat "from that equal creation theyderive ri

ghts." The revised final versionof the Declaration t

o some extentobscures the connection between t

heseclaims, saying only that two truths areself-evi

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

38/86

dent: that all men are createdequal and that all ar

e endowed by theircreator with certain inalienable

rights.Nonetheless, it seems fairly clear thatan un

derstanding of the claims to self-evidence made b

y the Declaration willrequire an understanding of

how theclaim to natural equality could bethought t

o be self-evident and anunderstanding of how it c

ould bethought to be self-evident that such anequ

ality implied an equality of rights.

The first claim, that it is self-evidentthat all men ar

e created equal, can beunderstood in a relativelys

traightforward way. If we think thatmen are by na

ture rational animals,then only those things that a

re rationalanimals are men. To say that all menare

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

39/86

created equal is just to say thateverything that is

a man has the natureof being a rational animal. B

ut this islike saying that all bachelors areunmarrie

d males. Just as no thingcould be a bachelor with

out being anunmarried male, so no thing could be

aman without being a rational animal."All men ar

e created equal" is self-evident in the way that "All

bachelorsare unmarried" is self-evident. Once we

understand what is being said, we seethat it must

be true.

The view that it is also self-evident thatbecause all

men are created equal theytherefore have equal r

ights can beunderstood as a special instance of th

efundamental idea of natural law.According to nat

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

40/86

ural- law theory, givenan understanding of the nat

ure of athing, we can derive from that how thatthi

ng should be used. But if this is true,since all men

have the same nature, itwould follow that all men

should betreated in the same way--that all menh

ave equal natural rights.

Universal Rights

The natural rights claimed by theAmerican revoluti

onaries were claimedon behalf of all men. They be

longed toAmericans, Englishmen, Frenchmen, and

Chinese. In thissense, the rights claimed were un

iversalrights, as opposed to the particularrights of

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

41/86

Englishmen, rooted in theparticular traditions of t

he Englishpeople. But in another sense, the rights

claimed were not truly universal. Theydid not inclu

de women or males ofAfrican descent who labore

d as slavesin the land of freedom. We will conside

rthe implications of these exclusionslater in this b

ook. Still, in a worldlargely ruled by tyrannical min

orities,the Declaration's claim that every manhad

both a right and a duty to resisttyranny, despite it

s false universality,had revolutionary implications.

Fromthe great upheaval of the FrenchRevolution,

which soon followed theAmerican example, to the

massivedemonstrations by students inTiananmen

Square in Beijing twohundred years later, the phil

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

42/86

osophicaldoctrine of natural rights has been apow

erful force in history. Indeed, eventhose excluded

by the Americanrevolutionaries, such as women a

ndAfricans, would eventually appeal to thephiloso

phy of natural rights to supporttheir own claims to

freedom andequality. In the chapters that follow

wewill examine some criticisms of thetheory of na

tural rights. We will alsolook at some alternative w

ays ofthinking about the fundamental issuesof poli

tical life, and we will exploresome of the ways that

the theory ofnatural rights has been revised orex

panded in response to thesecriticisms and alternat

ive ways ofthinking.

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

43/86

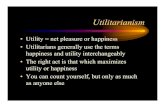

Utilitarianism

The theory of natural rights espousedby the Decla

ration of Independencedefends the revolutionary

politicalaction of the American colonists. TheDecla

ration claims that resistance toBritish rule was jus

tified, and evenrequired, by fundamental principle

s ofthe natural laws of morality. TheDeclaration of

Independence appearedin July of 1776. That sam

e year saw thepublication of An Inquiry into theNa

ture and Causes of the Wealth ofNations , written

by the Scottishphilosopher Adam Smith. Therelati

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

44/86

onship between the ideas of theDeclaration and th

e ideas formulated bySmith in The Wealth of Natio

ns iscomplex. As professor of moralphilosophy at

the University ofGlasgow, Smith had begun to dev

elop asystem of ethics that was in itsfoundations r

adically different from thesystem of natural law es

poused by theDeclaration. However, while Smith's

alternative system of ethics is clearlylurking in the

background of TheWealth of Nations , that work i

s notitself devoted to the problems of moralphilos

ophy. Its central concern is thescience of economi

cs. In this chapter wewill examine both Adam Smi

th's scienceof economics and the ethical theorysu

ggested by him.

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

45/86

Smith's EconomicsHow can a nation maximize the wealthit produces

? This is the central questionaddressed by Adam S

mith in TheWealth of Nations . Imagine a society i

nwhich each household produceseverything it con

sumes. Each familygrows its own food, makes its

ownclothing and shelter, and by its ownlabor sup

plies all its other needs. Such a society is

scarcely imaginable. Under difficultconditions, wh

ere the climate was harshor the soil poor, the hou

sehold mightdevote all its waking hours to labor a

ndstill not survive. Under favorableconditions the

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

46/86

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

47/86

Trade and the division of labor thusconstitut

e important sources of wealth .Smith also se

es a system of free marketsas conducive to t

he wealth of a nation. Asystem of free mark

ets is a system inwhich each individual is fre

e to enterinto contracts with any other indiv

idualto buy or sell goods or labor power.Wit

hin such a market system buyers

will look for sellers offering goods at thelow

est price, and sellers will look forbuyers willi

ng to pay the most for thegoods they have t

o sell. With buyers andsellers free to contrac

t with any otherindividual, no individual buy

er or sellercan say what the prevailing mark

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

48/86

etvalue of a commodity will be. Instead,pric

es are determined by the marketforces of su

pply and demand. If, as aseller, I ask for more t

han the prevailingmarket price, no one will buy fro

m me.If, as a buyer, I offer less than themarket p

rice, no one will sell to me. In asystem of competi

tive markets, pricesare determined by the impers

onalforces of supply and demand.

Smith calls prices determined by theforces of sup

ply and demand operatingin markets not affected

by unnaturalrestrictions on free competition the" n

atural prices" of commodities. Hecontrasts su

ch natural prices with theprices of commodities of

fered underconditions of monopoly, where onebu

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

49/86

yer controls the entire supply of acommodity: "Th

e price of monopoly isupon every occasion the hig

hest whichcan be got. The natural price, or thepri

ce of free competition, on thecontrary, is the lowe

st which can betaken." To be sure, a seller may, f

or aperiod of time, secure a price higherthan that

necessary to sustain thebusiness. If, for example,

anentrepreneur discovers a more efficientway to

produce a commodity, then he orshe can afford to

produce thecommodity for significantly less thant

he market price. At thispoint our entrepreneur has

somediscretion over how to price theproduct. Th

e product cannot be pricedabove the market price

, since then noone would buy it. Suppose then tha

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

50/86

t theentrepreneur offers the product at themarket

price. In this case he or she willmake higher- than

-average profits.Alternatively, the entrepreneur ca

n offerthe product at below the market price,atte

mpting to win buyers away fromcompetitors. In ei

ther case, the marketwill adjust. If the product is

sold atbelow the market price, competitorswill hav

e to adopt the more efficientmethods of productio

n in order to stayin business. If the product is s

old atabove-market price, entrepreneurs wil

lbe attracted into the industry by thehigher-

than-average profits, increasingthe supply o

f the commodity anddriving the price down.

I n either case,the price of the commodity willeven

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

51/86

tually fall to the lowest price sellerscan afford to ta

ke and stay in business.

This example illustrates two importantfeatur

es of free markets. One feature isthat compe

tition provides everyindividual an incentive t

o produce moreefficiently. Producers who can l

owertheir costs of production can, at leasttempor

arily, increase their profitmargins. On the other ha

nd, producerswho are less efficient than theircom

petitors will eventually be drivenout of business. B

ecause of thepervasive influence of this ince

ntive toproduce as efficiently as possible, as

ociety that chooses to organize itseconomic l

ife according to the principleof free competit

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

52/86

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

53/86

agency,the free market automatically adjuststhe

whole complex network ofinterconnected goods a

nd services toachieve new equilibrium prices such

that demand and supply of goods are inbalance a

nd no more efficient use ofexisting resources is po

ssible. In thefamous phrase of Adam Smith, f

reemarkets function as if guided by an"invis

ible hand" ensuring that the effortof each pe

rson to secure his or her ownhappiness is tu

rned to the benefit ofsociety as a whole .

The Wealth of Nations is an extendedargument fo

r a system of freeenterprise. At its most basic leve

l,Smith's argument is that the best wayfor a natio

n to maximize its wealth isfor it to adopt a system

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

54/86

of free marketsto govern its economic life. At th

e timeSmith was writing, Britain's economic

system was still marked by a variety oflaws

and regulations, many of themholdovers fro

m the earlier feudal era,that in one way or a

nother interferedwith or prevented free com

petition inthe production and sale of goods.

Smithargued that it would be in the interest ofthe

nation to do away with these lawsand regulations,

to adopt a system offree trade in which all govern

mentalrestrictions on commerce wereremoved.

The Wealth of Nations is a treatise ineconomic sci

ence. That is, it attempts tosay how a system of f

ree markets wouldin fact work and what the cons

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

55/86

equencesof adopting such a system would be. Int

his sense The Wealth of Nations isfundamen

tally different in aim from theDeclaration of

Independence. TheDeclaration attempts to s

ay how sociallife should be organized by app

ealing tolaws of nature that prescribe how

weshould behave, even though we do notal

ways actually behave in those ways. Incontr

ast, The Wealth of Nations isprimarily devot

ed to showing how asystem of free markets

would in factinvariably work out. Its primar

ycontent, the claims that free-marketsystem

s are efficient and self-regulating, is descrip

tive rather thanprescriptive. Nonetheless, The

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

56/86

Wealthof Nations does also have a prescriptiveint

ent; Adam Smith clearlyrecommends free enterpri

se as aneconomic system that we should adopt.L

et us turn now to a consideration ofthe prescriptiv

e theory underlyingSmith's recommendation.

The Principle of Utility

In The Wealth of Nations Adam Smithargues

that we should adopt a system offree marke

ts to govern economic life. Infact, lurking in

this "should" are twoquite distinct standpoi

nts: thestandpoint of self-interest and thest

andpoint of morality . The difference

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

57/86

between self-interest and morality isclear enough.

If I say you should see aparticular movie, most li

kely it isbecause I think you would enjoy it andtha

t it is in your self-interest to do so. IfI say you sh

ould keep your promise,most likely it is because I

think youhave a moral obligation to do so. Ofcour

se, we can imagine contexts in

which I say you should see the moviefor moral re

asons. Perhaps, forexample, I think the moviewou

ld convey to you the morallyrelevant suffering of p

eople in someremote part of the world of which y

ouwere unaware. It is also possible thatmy recom

mendation that you keep yourpromise appeals to

your self-interestrather than to morality. If, for ex

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

58/86

ample,you are in business and dependentupon re

peat customers, it is in yourself-interest to keep y

our promises toyour customers. Nevertheless, the

re is aclear difference between the demands ofself

-interest and the demands ofmorality. My self-in

terest aims at myown well-being. Morality r

equires me toconsider also the well-being of

otherpeople. The word should sometimesco

nveys a recommendation aimed atself-intere

st and sometimes conveys arecommendatio

n aimed at morality.

If we ask whether Smith'srecommendation t

hat we should adopta system of free market

s to governeconomic life aimsself-interest or

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

59/86

morality, the answer is that it aims atboth. T

he appeal to self-interest is clearenough. If we ad

opt a system of freemarkets, we will maximize the

totalamount of wealth produced by thenation. Thi

s will mean that there ismore available for each of

us. Now, ofcourse some individuals will stand tolo

se from the adoption of a system offree markets t

hose individuals whobenefit from governmental la

ws andregulations that prevent competition.Free e

nterprise is not in the self-interest of such individu

als. It is,however, in the interest of the rest of us,

who are not in a position to benefitfrom barriers t

o competition. Sincemost people are in this positi

on,Smith's argument is that a system offree mark

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

60/86

ets is in the self-interest ofmost people. Howeve

r, because such asystem would increase the

total amountof wealth produced by the natio

n, it alsowould increase the amount ofhappi

ness in the nation as a whole. Thisfact, assu

ming here that Smith is rightabout this, is th

e foundation for a moralargument for free m

arkets.

Suppose we adopt as a basic principleof mor

ality the principle that we shouldmaximize h

appiness. Suppose also thatwe are convince

d by Adam Smith that asystem of free marke

ts would maximizehappiness. Given these t

wosuppositions, it follows that we(morally)

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

61/86

should adopt a system of freemarkets. Our b

asic moral principle saysthat we should do

whatever wouldmaximize happiness, and S

mith'seconomic science has shown us that a

free-enterprise system would maximizehapp

iness. It follows that such a systemis morall

y desirable as well as desirableon grounds o

f self-interest.

The principle that we (morally) shoulddo wh

atever maximizes happiness isknown as the

principle of utility, on thegrounds that itreco

mmends as the morally optimalcourse of acti

on the one that is mostuseful to human bein

gs, creatures whoseek happiness. The philos

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

62/86

ophicaltheory that makes this principle thef

undamental principle of ethics isknown as ut

ilitarianism . Although theutilitarian idea is sugge

sted by AdamSmith, the English philosopher Je

remyBentham was the first to clearlypropos

e the principle as the singlefundamental pri

nciple of morality. In1789 Bentham, who co

nsidered himselfa disciple of Adam Smith in

economictheory, published his great work, A

nIntroduction to the Principles ofMorals and

Legislation . In this workBentham argued for

the principle ofutility as the single moral pri

nciple thatshould guide both individuals tryi

ng todecide what action to perform andlegis

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

63/86

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

64/86

o such legal rights wereclearly determinable, testa

ble by appealto the legislation creating them. On t

heother hand, claims about natural rightswere not

so clearly determinable. Is itobvious that all hum

an beings are soequal by nature that none can clai

m arightful authority over another? Is thereany w

ay, in principle, to resolvedisputes about claimed

natural rights?Bentham thought not. He regarded

claims about natural rights as"metaphysical," like

claims about howmany angels can dance on the h

ead of apin. He also regarded natural rights a

sunreal. A legal right, grounded in thehuma

nly created legal system, isenforceable. In c

ontrast, supposednatural rights are not enfo

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

65/86

rceable . TheAmerican and French revolutionaries

proclaimed a universal right to liberty,but even th

ey admitted that for themost part, people were no

t in fact free.Slavery and tyranny were all toocom

mon. The supposed universalnatural right to libert

y was empty.Bentham's view is nicely summed up

inhis claim that " natural rights is simplenonsense

," and that the "natural andimprescriptible rights"

such as thoseclaimed in the French Declaration of

Rights are "nonsense upon Stilts."

In part, Bentham's hostility to the ideasof n

atural law and natural rights was areaction t

o the use of those ideas tooppose change an

d reform. Bentham'sfundamental aim was to

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

66/86

persuade theEnglish parliament to undertak

e athoroughgoing reform of England'slaws. I

n Bentham's view, the laws ofEngland were profo

undly warped toserve the interests of a privileged

elite.Not surprisingly, many of thespokesmen for t

his privileged eliteopposed the reforms champione

d byBentham. These opponents of reformoften de

fended their privileges as rightsbelonging to them

by the laws of nature.Bentham regarded this defe

nse as asubterfuge, one in which impressive bute

ssentially empty words served "as acloke, and pre

tence, and aliment, todespotism." Having encoun

tered suchbaseless appeals to natural law andnat

ural rights, Bentham came to regardall such claim

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

67/86

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

68/86

rinsically valuableand things that are extrins

icallyvaluable. Things that are intrinsicallyva

luable are things that are valuable inthemse

lves. Things that are extrinsicallyvaluable ar

e things that are valuable asa means to som

ething else. Money is agood example of som

ething that isextrinsically but not intrinsicall

yvaluable. In itself it is only paper, orordinary m

etals mixed with traces ofgold or silver. What mak

es moneyvaluable is that it is a means foracquirin

g other things we value--likefood, clothing, shelte

r, or other goods.Truckloads of money would be o

f novalue to a person stranded on an islandwith n

o way to use that money toacquire other goods.

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

69/86

If money has only extrinsic value, whatthings hav

e intrinsic value? At firstglance it looks as though f

ood, clothing,and shelter would be things that arei

ntrinsically valuable, since, unlikemoney, they app

ear to be valuable inthemselves rather than for ot

her thingsthey can bring us. But is this always so?

Shelter may be of no value in a tropicalparadise, a

nd clothing might be equallyuseless there. Even fo

od can lack valuein certain circumstances. A dying

person may find swallowing,intravenous

nutrition, and feedingtubes all painfully uncomfort

able. For such a person food only prolongs

suffering. Bentham argues that forhuman bei

ngs there are only two thingsthat are intrins

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

70/86

ically valuable: pain,which has negative intri

nsic value, andpleasure, which has positive i

ntrinsicvalue. The reason we value food is thatn

ormally it brings us pleasure--in theeating of it, in

its capacity to bring anend to the pain of hunger,

and in itscapacity to sustain the life necessary fort

he enjoyment of other pleasures.When, as in the

case of the dyingpatient, food brings only pain, it

ceasesto be valuable for us. What is desirablefo

r us as human beings is to maximizehappine

ss, to secure the most favorablebalance of pl

easure over pain that ispossible for us to ac

hieve. All other

goods are valuable to us only

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

71/86

extrinsically, as means to happiness.

Utilitarianism and Egoism

It is important to distinguish utilitarianethic

s from the ethics of egoism. Theprinciple of

ethical egoism is that eachof us always shou

ld act to maximize hisor her own happiness.

From the pointof view of ethical egoism, the

happinessof other people should matter to

meonly insofar as their being happy makes

me happy. If I am an egoist, only myown happin

ess is intrinsically valuable.It is my own happiness

that I aim tomaximize. In contrast, for a utilita

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

72/86

rianethics, the happiness of every person isi

ntrinsically valuable. To act accordingto utili

tarianism, I must calculate theexpected effe

ct of alternative acts uponthe happiness of e

very person affectedby those possible acts.

I should then dothe act that, among these p

ossible acts,has the optimal outcome in term

s of thetotal happiness produced. If a casesho

uld arise where performing aparticular action maxi

mizes the totalamount of happiness possible in ag

roup of people, even thoughperforming that partic

ular action makesme very unhappy, utilitarianism

saysthat nonetheless, that particular actionis what

I should do. For example,suppose I can save the

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

73/86

lives of manypeople, thereby creating greathappin

ess, but I can do this only bysacrificing my own lif

e. Ethical egoismwould say that I should not sacrif

icemyself, while utilitarianism says that Ishould sa

crifice myself. Egoism is

selfish. Utilitarianism is not.

Utilitarianism and

Majoritarianism

It is also important to distinguish theprinciple of u

tilitarianism from theprinciple of majoritarianism.

Themajoritarian principle would say thatthe right t

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

74/86

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

75/86

arian principle.

In this example of the differencebetween utilitaria

nism andmajoritarianism, the key thing is thediffer

ent intensities of the preferencesof the majority a

nd the minority. Thechoice between X and Y make

s a biggerdifference to the members of theminorit

y than it does to the members ofthe majority; the

choice between X andY has a more intense effect

upon theirhappiness. Because of this difference ini

ntensity, the selection of Y over X maymaximize h

appiness even though X ispreferred by a majority

over Y.

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

76/86

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

77/86

uce a somewhat lesser amount ofhappiness. How

ever, if the greaterhappiness is, though possible,

highlyunlikely, while the lesser happiness ishighly

likely, then the aim ofmaximizing happiness may

be bestserved by doing the act that aims at theles

ser, though probable, payoff.

Bentham considers a number of factorsthat, like i

ntensity, duration,and probability, should be consi

dered in trying to determine which among the

alternative possible actions would

maximize the total amount of happiness

produced. We need not consider each ofthese fact

ors here. Each is acomplicating consideration, but

none ofthem affects the basic idea of theutilitaria

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

78/86

n approach: The right thing todo in any situation i

s whatever willmaximize happiness. Bentham tho

ughtthat this principle provides thefoundation for

a scientific approach toquestions of morality. Conf

ronted witha choice about what to do, theutilitaria

n principle gives us a formula

for determining what is the morally

correct thing to do. Having identifiedthe possible a

ctions before us, we haveonly to calculate, for eac

h of thesepossible actions, the expected payoffs i

nterms of pleasure and pain, for eachaffected indi

vidual, of the performanceof that possible action.

Havingdetermined these payoffs for eachindividual

person, suitably refined byconsideration of the du

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

79/86

rations,intensities, probabilities, and othervariatio

ns of the pleasures and painsproduced, we need o

nly calculate fromthis data which among the alter

nativepossible actions before us has thehighest ex

pected payoff in terms of thetotal happiness prod

uced for society asa whole. From this point of vie

w,questions of morality are decidable bythe meth

ods of social science andelementary arithmetic.

Of course, in practice this would not bean easy un

dertaking. In any realsituation of choice we do not

have thetime to determine the happiness payofffo

r each affected person and probablycould not dete

rmine the payoff for eachwith any degree of precis

ion if we didhave the time. Nonetheless, the ideal

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

80/86

utilitarian calculus gives us a way ofdetermining in

principle what themorally right course of action is

.Further, the utilitarian calculus canfunction as a r

egulative ideal. Inpractice we make a very rough

estimateof the expected outcomes of the

alternative possible actions before us,but this rou

gh estimate is one that canbe corrected by increa

sed or moreaccurate information. The ideal calcul

usidentifies the kinds of information thatwould be

relevant to making suchcorrections. It may, as Be

ntham says,"always be kept in view."

Utilitarianism and the

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

81/86

Common Rules of Morality

In practice, in the making of decisionsin the every

day world, people areguided by a variety of moral

rules.Among these rules are principles suchas tell

the truth, do not harm innocentpeople, pay your d

ebts,help people in need, and a host of otherfamili

ar maxims. Bentham did not deny

that these maxims were generally validmoral princ

iples. But, he argued, it wasbecause these principl

es are generallyconducive to happiness that they

aremorally right. Thus, he argued, theprinciple of

utility explains what it isthat makes these maxims

generallyvalid moral principles. The principle ofutili

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

82/86

ty is the single fundamentalprinciple of morality. T

he maxims ofordinary moral life

are applications ofthe principle of utility to commo

n typesof human interactions. Usually thesemaxi

ms, if followed, do promotehappiness. It is for thi

s reason that theyare generally valid moral princip

les. Butsometimes these maxims do not hold.Trut

h telling, for example, is usuallymorally right, but

most of us think thatthere are some cases when

we shouldnot tell the truth. So-called white lies

are one sort of exception to the rule. Thedepartin

g guest does the right thing intelling the host how

much the eveningwas enjoyed even though the g

uest mayhave much preferred to have beenelsew

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

83/86

here. To tell the truth on such anoccasion would c

ause useless distressand unhappiness while the ki

ndly liecauses happiness and does no harm.There

are also occasions of a moreserious nature when

truth telling wouldnot be the morally right course

ofaction. Suppose, for example, that amale friend

shows up one evening,enraged, drunk, waving a

gun, andwanting to know where his girlfriend is.S

hould you tell him the truth? Surelynot, since to d

o so risks greatunhappiness. Bentham argues that

it isone of the virtues of utilitarianism thatit explai

ns why we should not tell thetruth in these cases.

Such cases showthat happiness is the deeper aim

ofmorality and that the maxims ofeveryday moral

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

84/86

life should beunderstood as rules of thumb that h

oldusually but not always. The ability ofthe princip

le of utility to explain whythe principles of everyda

y morality weregenerally binding, and at the same

timewhy they were not binding in somecases, pr

ovided a powerful argument infavor of Bentham's

utilitarianism.

Utilitarianism and the

Politics of Reform

In the early years of the nineteenth

century, utilitarianism largely

supplanted natural-rights theory as the

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

85/86

dominant political philosophy of the English

speaking

world. Presentingitself as a sober, scientific altern

ative tothe revolutionary metaphysics ofnatural la

w, utilitarianism nonethelessprovided a philosophi

cal foundation for

radical reforms of existing political institutions.In

England, by the middle of thenineteenth century, t

he fundamentalgoals of the reform movement had

coalesced into a coherent overallconception of ho

w society should beorganized. This is the concepti

on ofwhat is now known as classicalliberalism. In

the next chapter we willexamine the fundamental f

eatures ofclassical liberalism and see how modern

-

8/11/2019 Natural Rights Utilitarianism Edited Portion

86/86

conservative thought emerged as aphilosophical a

nd political alternative toliberalism.