Naditu Women in Old Babylonian Nippur

-

Upload

alberto-nonimo -

Category

Documents

-

view

101 -

download

2

Transcript of Naditu Women in Old Babylonian Nippur

THE SOCIAL ROLE OF THE NADITU

WOMEN IN OLD BABYLONIAN NIPPUR *)

BY

ELIZABETH C. STONE

State University of New York at Stony Brook

To date, our understanding of the Old Babylonian naditu institution

has been based almost entirely on the information contained in the

Sippar texts. Rich though it is in data on the rights and activities of the

naditus, the Sippar corpus is meager indeed in its documentation of the

rights and activities of the male segment of its population. The evidence

suggests that the preponderance of naditu texts is more the result of

selective sampling than a true reflection of Old Babylonian economic

activity at Sippar. An examination of the contracts from Sippar shows

that although men are participants in some of the transactions, in

nearly 70% of the texts one or both participants are women, in most

cases described as naditus. Furthermore, in of the cases where a

record exists of a transaction between a man and a naditu, the role of

the naditu is such that she would have been the one to keep the text;

i.e. the recipient of property, lessor of property, ctc, I). This evidence

suggests that the majority of the tablets must have been found in the

houses of the naditus. Since the Sippar naditus are known to have been

cloistered 2), it seems safe to assume that only the cloister suffered the

51

attentions of tablet hunters. The Sippar sample, then, must be ap-

proached with a full understanding of its limitations.

At Nippur, the situation is quite different. Of the approximately five hundred contracts that are available for study 3), only about i o% concern naditus, and the pattern of excavations at Nippur has been

such that these contracts cannot have been derived from a single area 4).

Thus, at Nippur it is possible to study the naditus within the broader

context of the society as a whole. Not only can we compare the struc-

tural-functional attributes of the naditu institution, but it becomes

52

possible to assess the role played by the naditus in the social dynamics of Old Babylonian Nippur.

The earliest contracts from Nippur date from the reign of Bur-Sin,

in the middle of the Isin-Larsa period, and are as early as any contracts

from other Mesopotamian cities. The latest text dates to the second

year of Iluma-ilu, equivalent to year 30 of Samsuiluna 5), giving a total

time span for the Nippur contracts of about two centuries. The end

of our contract record appears to coincide with an abandonment of

Nippur of several centuries' duration 6). This abandonment followed

an economic crisis in year eleven of Samsuiluna that had had a profound

impact on Nippur's population structure, and had resulted in the

abandonment of the southern cities. Old Babylonian occupation

continued, however, for over a century longer at the northern cities,

like Sippar 7). Three separate but related social institutions can be identified from

the textual record. These institutions show markedly different struc-

tures, and although overlapping they were not entirely contempo- raneous. The most traditional and the earliest social groups were the

patrilineal lineages, where membership was based on kinship ties. The

most innovative, and the social group best evidenced at the end of

Nippur's occupation, was the temple ofl-ice group, where membership was based upon institutional ties. The third group, and the one with

which we are primarily concerned in this paper, was the naditu institu-

tion in which both kinship and institutional ties were important.

53

Before entering into a more detailed description of the more salient

features of these three social institutions, it must be emphasized that

these models only describe that small percentage of the population whose activities were recorded in contracts. In addition, although some aspects of these models may be applicable to the social structure

of other Old Babylonian cities, this cannot be assumed. Indeed, an

examination of the contractual records of other cities suggests that the

unique aspects of each Old Babylonian city may outweigh their common

features 8). Thus the social institutions described below apply only to

the property-owners of Nippur. Based on information contained in the contracts, it has been possible

to trace genealogies four to six generations deep whose structural and

functional manifestations closely parallel those of modern Middle

Eastern lineages, thus permitting extrapolation from modern observa-

tions 9). Ideally, the Middle Eastern segmentary lineage is an endo-

gamous kinship group within a larger tribal matrix which acts as a

corporate group in subsistence, military and judiciary activities. In

reality, both in the present and in antiquity, the intrusion of state power

greatly modifies these activities.

By the time of the earliest contracts from Nippur, not only had the

judicial and defense functions been taken over by the state, but in-

dividual property ownership had been imposed, resulting in a trans-

formation of the lineages. These contracts are primarily concerned

with the transfer of this individually owned field, house and temple office property, all of which could be bought, sold and inherited.

54

Alienation of house and especially field property was apparently restricted to lineage members 1°), but temple offices 11), which were a

less traditional form of property 12), could be freely bought and sold.

It is through an examination of the movements of property and of

the people involved, both as principals and as witnesses, that it is

possible to deduce some aspects of the lineages, and indeed of all

three social institutions.

Although each identifiable lineage exhibits certain unique features, a basic pattern is shared by all. Lineage members generally owned

contiguous plots of land and similar temple offices; property exchange

mostly took place within the lineage, while outsiders were rarely chosen to act as witnesses to such contracts. Although leadership was

little evidenced, in some cases it may be that control of certain temple offices had conferred a leadership role. In general, the picture presented is one of several self-contained economic units.

The temple office group, on the other hand, was a single open-ended

group whose only tie was temple offices ownership. Although temple offices were apparently not alienable until around 1800 B.C, 13), they were heritable from the time of our earliest contracts. Although we do

not know what temple functions offices holders were expected to per-

form, it is clear that they were involved in the state judiciary system. The majority of the witnesses to court cases were temple office holders,

attesting to their presence at these proceedings. More important for

its members, however, was the redistributary function of the temples. Unlike ownership of land, temple offices were divided into shares,

55

expressed in the number of days in the year for which the office was

held, or in some cases as fractions of the total offices. Temple office

ownership provided rights to a share of temple revenue, apparently

taking the form of a right to eat part of the sacrifice 14). Since the tem-

ples drew their revenues from scattered fields, and since they included

large storage capacities, they were less likely to be seriously affected

by the local, short-term variations in water supply and fertility that

afflict southern Mesopotamian agriculture. Like the traditional lineages,

temple offices provided their owners with the necessary risk-sharing attributes to guarantee their security.

It is not clear whether it was this bond of common activity, or the

free alienability of their property which drew temple offices holders

together, but by i73o B.C. the temple office owners of Nippur formed

a single economic unit. The functions that were traditionally vested in

the lineages were now taken over by the group as a whole. Property,

especially temple officers, was freely exchanged, and witnesses to these

transactions were drawn from within the group. The group was large, with several hundred members identifiable in the Nippur sample, and

was based on institutional ties rather than on kinship. The third Nippur social institution, that of the naditus, combines

elements of both the lineages and the temple office group from Nippur, and of the naditu institution at Sippar. These similarities must be

related to the integrative needs of the Nippur social system on the one

hand, and to institutional parallels with Sippar on the other. The actual

manifestations of the Nippur naditu institution, however, are unique to

that institution and to that city. There exist many superficial resemblances between the naditus of

Nippur and those of Sippar. At both cities the naditus were unmarried

virgins 15) who were able to engage in economic activities like men.

56

Were it not for this economic role we would have little information

on their social position. At both Nippur and Sippar a specific area of

the city was set aside for the naditus. At Sippar we know that this took

the form of a cloister, an area from which men were excluded. At

Nippur the cloistered aspect is less clear. Instead of using the Sumerian

word for "cloister" (ga-gi4-a), at Nippur the area is simply described

as the "place of the nad7tus" (ki-lukur-ra). In addition, men are not

unheard of as owners of house plots in this area at Nippur (see table i) 16).

Table i

Sale of House Plots in the "Place of the Nadttus" at Nippur

Although naditus at both Nippur and Sippar owned and exchanged

property of all kinds 1'), it appears that the mechanisms by which they

57

were dedicated to the god and provided with this property differed.

These differences may be related to the fact that different gods were

involved. Whereas the naditus from Sippar were usually dedicated to

the god Samas 18), those from Nippur were dedicated to Ninurta 19). The establishment of a naditu at Sippar apparently involved a ritual in

which a change of name occurred. This is not evidenced at Nippur 20). In addition, while the naditus at Sippar received their property through inheritance either from their fathers or from another naditu, those at

Nippur received gifts of property from their father but were apparently excluded from the inheritance process 21).

Although information on the establishment of a Nippur naditu

is virtually nonexistent, one group of texts 22) may provide some in-

sight into this problem. We cannot, however, be sure that the activities

recorded in these texts are representative of the city as a whole, but

they are at least suggestive. The earliest text, ARN begins with

a list of the property that was given to Beltani during her father's

lifetime. Following a list of the household goods, grain, and a slave

girl with which she was provided, the text continues with a list of the

real property that she received. The most substantial plot was an 18

iku field that was given to her by her father's sister, herself a naditu.

58

To this was added a 3 iku plot that was provided by her father and her

eldest brother. In the final section of the text a monthly ration of

grain and oil and an annual ration of wool was established which was

to be given to her for the rest of her life by her brothers.

The text suggests that the investiture of a naditu involved three

types of property transactions, quite apart from any rites which may have been associated with this event. In the first place the naditu, like

any other girl, was apparently entitled to receive those household

effects that she would normally have received on marriage as her dowry.

The list of households goods provided at the beginning of the text is

mirrored in both modern Arab 23) and ancient Mesopotamian 24) dowries. The second part of the transaction provided the naditu with

real property. In this instance, most of the real estate was provided by a paternal aunt, herself a naditu. Her father merely gave her a field plot

similar to those he was later to give to his younger sons. It is possible that only those girls with naditu relatives could themselves enter the

naditu institution, but this cannot be proven. It is clear, however, that

in some families naditus were common (see fig. 1) 25), while in others

they were absent 26). The third part of the transaction ensured that the naditu would be

free from want during her lifetime. The very high level of support

recorded in ARN 29 was apparently unusual, for some thirty years

later, long after her brothers had received their inheritance, a new

agreement was made whereby the level of support was reduced. This

document, unlike ARN 29, was a sworn, witnessed document, sug-

gesting that the power of the state legal system was needed to ensure

compliance.

59

This text, PBS 8/2 text 116, includes a rather mysterious clause

which may help to shed light on the relationship between a naditu and

her brothers. Not only would the brothers forfeit their inheritance were

they to withdraw their support, but the text states that any heir who

sells his (or her?) field before Beltani's death would lose all rights to

their father's property. This last phrase suggests that the brother's

field holdings were somehow held, perhaps as collateral, to ensure

Beltani's maintenance. An alternate and more plausable interpretation, and one of considerable significance for an understanding of the prop-

erty rights of the naditus, is that the heirs were prohibited from selling Beltani's field property during her lifetime 2'). If this latter inter-

pretation is accepted, then we must assume that a naditu's land holdings

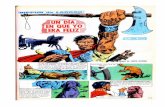

Fig. i : The Imgua Genealogy.

Ai = Imgua, Bi = 9alurtum, Bz = Awiatum, B3 = Ziatum, B4 = Lugatum, B5 = Kunutum, B6 = Ibni-Enlil, Ci = Narubtum, C2 = Dusuptum, C3 = Tari- bum, C4 = Lugal-azida, C5 = Masqum, C6 = Ur-dukuga, C7 = Sin-nasi, ,C8 =

Arad-Iminbi, C9 = Beltani, C i o = Issu-saran, Cm = Ninurta-abi, Ci2 = Ninurta-

gamil, Ci 3 = Idiatum, D = Damiq-ilisu, D2 = Inbi-ilisu, D3 = Imgur-Ninurta, Ei = Lipit-Istar, E2 = Sin-eribam.

60

were still largely controlled by her brothers, even if they were legally hers.

That a close relationship existed between a naditu and her brothers

is made clear by three court cases. ARN 120 supports the suggestion that a brother may have had some control over his naditu sister's

property transactions. Although the text is badly damaged, it appears that Naramtum's brother brought suit against her because she had

sold a field that he had given her and that had once been part of their

father's inheritance. The exact significance of this text is hard to

assess, but it seems to support the supposition that the economic

activities of a naditu and her brothers were not unrelated.

Two other court cases, ARN 101 and PBS 8/1 text 8229) suggest that brothers also served as protectors of the rights of their naditu

sisters. In PBS 8/1 text 82 a brother goes to court to protect his sister's

interests. As is often the case with court cases, in spite of the tablet's

undamaged condition, the meaning is not clear. Nonetheless, the last

few lines suggest that in this instance the financial dealings of brother

and sister were hopelessly intertwined. Where PBS 8/ text 8 z is unclear, ARN 101 contains little ambiguity. In this case a third, apparently

unrelated, party was responsible for maintaining the naditu Lamasum.

When, for five months, he had failed to provide her with this sum, her

brother took him to court to force compliance.

61

Although these court cases are rare, they nevertheless underscore

the close relationship that existed between a naditu and her brothers.

When, however, we examine the actual property transactions of the

naditus, we find no examples of an exchange of property between a

naditu and a sibling. Since we do have two instances of a naditu ex-

changing property with a first cousin 3°), it may be that the ownership distinctions between a nad7tu's property and that of her brothers was

sufficiently unclear that no exchange text was necessary. Indeed, BE

6/2 text 6 suggests that if a distinction was made between property owned by a brother and that owned by his naditu sister, this distinction

did not preclude the alienation of the property by a sibling. In this

instance, the text describes a house plot as belonging to Enlil-nisu,

but it is his naditu sister, Betatum, who is recorded as the seller.

If naditus had close social and economic ties with their brothers,

they maintained an equally close relationship with other naditus. In

Tables 2 and 3 we see that naditus frequently exchanged property with

other naditus and that they often witnessed each other's texts. The

naditu institution thus exhibits the same pattern of solidarity as has

been observed for the lineages and for the temple office group. Naditus also occur in adoption documents. Unfortunately, the three

naditu adoptions that occur in the Nippur corpus are all so badly

damaged that we cannot even tell whether the naditus were the adopters or the adoptees 31). The other parties in these adoptions were men in

62

two cases, and a wife (widow?) in the other. A possible interpretation of this material is that at Nippur, as at Sippar, naditus occasionally

adopted others to ensure their future support and protection. Unfor-

tunately, none of the texts is well enough preserved for us to be sure.

The naditus' need of support and protection is also reflected in their

dealings with slaves. Slaves occur but rarely in the Nippur corpus, yet of the four manumission texts preserved 32), in two instances 33) the

slave owner was a naditu. In addition, in ARN29 (see above), the list

of household goods provided for the establishment of a naditu includes

the gift of a slave girl. Since most of the other texts dealing with

slaves concerned the activities of other isolated, unmarried women, it

is possible that women were generally secluded before marriage, and

that if they lacked the services of other members of their family, they needed slaves to go abroad for them 34). If this were the case, then

perhaps we should understand the cloistered aspect of naditus as

resulting more from their unmarried status, than from their special ritual status. If it was indeed the case that naditus were secluded, this

would aid us in our understanding of the relationship between a

naditu and her brothers. Her secluded state would have forced her to

rely on others to perform public actions.

In summary, then, the Nippur naditus operated in two spheres. On

the one hand they maintained close ties with their siblings which

involved both economic ties and dependancy relationships, while on '

the other, they were incorporated into the naditu institution and made

63

many of their economic transactions, and in all probability their

social ties, with other members of that institution.

With the descriptive account of three of the major institutions 35) that characterized the Old Babylonian social organization of Nippur now completed, it is appropriate to examine their interaction, focussing

especially on the role played by the naditus. In the following pages it

Table 2

Nippur Nadatu Transactions

Table 3

Nippur Nadïtu Texts

64

is our purpose to attempt an understanding of the integration of the

nad7tus with members of both the kin-based lineages and the occupation- based temple office group. Since our aim is to achieve some insight into the role played by the naditus in the social dynamics of Old Baby- lonian Nippur, we will examine our data within a diachronic framework.

Although no legal contracts have been preserved dating from the

early part of the Isin-Larsa period, it is to this period that we must

seek the background to all subsequent events. Early Isin-Larsa social

organization must have consisted of lineages whose power was based

upon the communal ownership of considerable amounts of house,

field, orchard and presumably temple office property. This power,

though, was struck a mortal blow by the imposition of individual land

ownership that apparently took place at this time. The reasons for this

imposition remain obscure; the city governors may have imposed

individual ownership for reasons of taxation or conscription or,

alternatively, the tribal elements of the society may have been forced

into the urban centers by the political unrest that characterized this

period, and may thus have fallen under the more firm control of the

urban state governments 36). Whatever the reason behind it, such an

imposition of individual property ownership would have led to the

existance of a land-holding system which was incompatible with the

social system.

Ideally, in a segmentary lineage system of the type commonly

found in the Near East, property relationships bolster the social order.

With the imposition of individual property ownership, however, we

see a social organization based on principles of communal action but

faced with the realities of individual property ownership. Only under

circumstances of communal land ownership with lineage control of

resource redistribution, were the risk-sharing attributes so necessary

for surviving the vicissitudes of Mesopotamian agriculture attained.

65

With private ownership the lineages became economically vulnerable,

while at the same time these new realities forced a substantial alteration

in their internal power relationships. If traditional patterns were

followed, then the power of the lineages would have been based upon the amount of land controlled by the lineage as a corporate group, and

by the number of men who could be mustered for community action.

The imposition of individual property ownership stripped the lineages of this basis for their political power.

The effect of the imposition of individual property ownership was

a freezing of the power relationships within the lineages. The lineage

leaderships would have received more land at the time of land registra- tion than the weaker branches, thus allowing them to maintain econo-

mic control of their lineage, even when the political climate within

the lineage went against them 3'). Under such circumstances the

social distinctions within the lineages were undoubtedly reinforced. It

was perhaps in this climate that the naditus began to play a significant economic role in the community.

Information on the early history of the naditu institution is not

available, but it must have been developed as a response to the social

and spiritual needs of the time. Perhaps then, as now, the daughters of tribal leaders, constrained by endogamy and rank, often had diffi-

culty finding a suitable spouse 38). Entrance into the naditu institution

would have provided a viable alternative. The god would supplement the protective role already played by her brothers, while the economic

arrangements would free her from want and allow her to establish an

independant household. It is not surprising that such an institution,

whose membership included the sisters and daughters of many of the

more influencial men of the city, would come to play a significant role

in the community. As lineage power began to be based on the land holdings of the

66

lineage leadership, rather than of the group as a whole, new strategies aimed at the concentration of property in the hands of that leadership

came into being. In the written record we find some instances in which

certain kinds of property, such as temple o?ces, remained undivided at

inheritance and were passed on intact to the eldest son. This evidence

suggests a strengthening of the principles of primogeniture, principles that were incompatible with the egalitarian aspects of lineage organiza-

tion. In addition, in order to prevent excessive fragmentation of land

holdings at inheritance, some sons appear to have been excluded from

property inheritance. Our evidence suggests, although no specific

records exist, that these disinherited sons received their patrimony in

the form of moveable commodities during their father's lifetime; thus

achieving early independance. Our only record of these individuals,

however, is when they used their accumulated wealth to purchase

property from their inheriting brothers.

In addition to these strategies designed to consolidate property

holdings, the lineage leaderships were actively engaged in the purchase

of new property. Unfortunately, due to the alienation restrictions on

land, the leaderships could only purchase real property from the more

minor branches of their own lineages. Such transactions resulted in an

internal polarization of wealth which threatened lineage solidarity and thus the very fabric of the social system 39). New strategies were

needed whereby property exchange could take place between members

of disparate lineage leaderships if the lineage system were to survive.

It was in this context that the naditu institution came into its own.

In the early days of Rim-Sin, around 1800 B.C., naditus were the

only members of society who had ties with more than one social

institution. On the one hand they were members of their natal lineages, while on the other they belonged to the naditu institution. The records

of their economic transactions reflect this dual role, as they exchanged

property with both their kinsmen and with other naditus. Since the

naditus appear to have been largely drawn from the wealthier echelons

67

of society, they were ideally suited to act as liaisons between lineage

leaderships. It seems likely that men could and did exchange property with members of other lineages, channeling the transactions through their naditu sisters and cousins. Such activity is reflected in the

textual record. Fig. 2 shows that the majority of naditu transactions fall

during the years of the reign of Rim-Sin of Larsa, and indeed that at

this time their activities far outweigh their numbers relative to the

society as a whole. I believe that this spate of naditu activity came about

primarily as a response to the difficulties in which the lineages found

themselves.

Although the nadatu institution proved useful to the lineages for

a time, the principles upon which it was based were antithetical to those

of the lineages. Membership in the institution was apparently based

largely on wealth and prestige, while property ownership was strictly

personal and individual in nature. Membership in the lineages, on the

other hand, was based on kinship, while ideally property was owned in

common. In addition, although the naditu institution provided a

mechanism whereby property could be exchanged between lineages, it

was not only limited in scope and unwieldy in practice, but it failed

to provide the risk-sharing attributes that had been robbed of the

lineages when individual property ownership had been imposed. At

Nippur, another institution, the temple, entered the private sector and

provided the lineages with a new vehicle for property exchange while

permitting them to join a large, risk-sharing, redistributive institution

that served some of the same functions as had the traditional lineages.

Although some of the earliest contracts from Nippur concern the

inheritance of temple ofhces, no record exists of their sale until around

1800 B.C., the time of the height of the power of the naditu institution.

Although it is dangerous to argue from negative evidence, one may

suggest that temple offices were not considered alienable property until late in the Isin-Larsa period. The fact that the traditional aliena-

tion restrictions that affected house and field property were absent in

the case of temple offlces strengthens this suggestion. When temple offices became exchangable property, their freedom from traditional

68

alienation restrictions made possible the establishment of direct eco-

nomic ties between male members of different lineages. These direct

ties were apparently preferable to the indirect ties provided by the

naditu institution. By the time of Hammurabi's conquest of Nippur in

1763 B.C., these new possibilities had resulted in a decline in the

importance of the naditus (see fig. 2). At the same time, the strength-

ening of the ties between temple office owners, most of whom were

members of lineage leaderships, increased the economic disparity between the leadership and the more minor branches of the lineage,

furthering the alienation of the latter, and threatening the very existence

of the lineages. The presence within the economic system of freely alienable temple

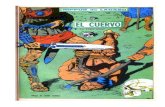

Fig. 2 : Occurrences of Nadïtus and Men in Exchange and Loan Documents.

Note: This graph is based on all dated texts which concern the permanent ex-

change of real estate and the loan of commodities. Other types of texts were not used since they did not usually concern naditus. The graph is based on the tabulation of transactions for each half century covered by our texts. Since there were approxi- mately five times the number of men who were involved in these transactions than women, the number of naditus recorded for each half century was multiplied by five in order to provide a comparable graph.

69

office property began to erode the traditional alienation restrictions on

land. With the economic crisis in 1 7 3 9 B.C. which drove out the poorer members of society, perhaps even including some naditus, lineage unity and alienation restrictions came to an end, and with them waned the

last vestiges of naditu power. For the last twenty years of Nippur's Old Babylonian occupation, the city's private economy was dominated

by a large, loosely integrated group of temple office holders, for whom

kinship was of less significance in economic matters than institutional

ties.

The rise of the temple office group and the eclipse of the naditus

must be seen as a purely local phenomenon. Only at Nippur, the

religious center of Mesopotamia, could and did temple offices attain

such significance. At some cities, such as Larsa, Kutalla and Dilbat,

it seems that a few individuals, perhaps originally the leaders of large tribal segments, apparently came to control large amounts of real

estate; enough perhaps for them to act as redistributive centers for

their followers, as did the pre-land-reform khans of Iran 40). At Sippar, the evidence suggests that the minor importance of

temple offices in that city allowed the naditu institution to attain its

full economic potential. No matter how one evaluates the original

findspots of the Sippar tablets, the economic importance of the Sippar naditus remains unquestioned. The process of naditu control of private real estate continued, until by the end of the Old Babylonian period, much of the real property of Sippar was apparently in the hands of a

few families, families that were dominated by naditus.

In conclusion, based on the evidence from Sippar and Nippur, we

are able to approach an understanding of the role played by the naditu

institution. It seems likely that the institution began by fulfilling

spiritual and social needs quite separate from its later economic func-

tions. However, with time the institution was transformed by the

changing social, economic and political climate. The imposition of

individual property ownership radically altered the socio-economic

70

landscape, and with it the economic potential of the naditus. With

the disintegration of the lineages, the original social constraints that

had perhaps resulted in the establishment of the naditu institution were

slowly lifted, while at the same time naditus were encouraged to play a more active part in the economy. Existing institutions must adapt to

the changing social landscape or they will become obsolete, and it is

thus that we should understand the various roles of the naditus in the

different cities in which they are evidenced.