Multi-focused strategy in value co-creation with customers: Examining cumulative development pattern...

-

Upload

xiang-zhang -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Multi-focused strategy in value co-creation with customers: Examining cumulative development pattern...

Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Int. J. Production Economics

0925-52

doi:10.1

n Corr

E-m

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijpe

Multi-focused strategy in value co-creation with customers: Examiningcumulative development pattern with new capabilities

Xiang Zhang a,n, Chen Ye a,b, Rongqiu Chen c, Zhaohua Wang a

a School of Management and Economics, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 100081, PR Chinab School of Economics and Management, University of Science and Technology, Beijing, Beijing 100083, PR Chinac School of Management, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430074, PR China

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 29 September 2010

Accepted 11 March 2011Available online 29 March 2011

Keywords:

Tradeoffs

Cumulative theory

Competitive capabilities development

Customer participation

Value co-creation

73/$ - see front matter Crown Copyright & 2

016/j.ijpe.2011.03.019

esponding author. Fax: þ86 10 68912483.

ail address: [email protected] (X. Zhang

a b s t r a c t

The previous research of capabilities development has largely focused on the established capabilities,

i.e., quality, delivery, cost and flexibility, although there are a wide variety of possible dimensions. Few

studies report the accumulation effect about adding new capabilities on an established base in a

different strategic setting. Motivated by the increasingly important strategy of value co-creation with

customers, this study aims to examine the patterns of capability development with consideration

of adding service and customerization capabilities. Taking a downstream-focused view and based on

the data collected at Chinese firms, this study extends the cumulative theory to the scenario of

value co-creation with customers by identifying the mutual enhancement effect when adding new

capabilities on an existing base. Specifically, this study finds that firstly, new capabilities (i.e. service

and customerization) and established capabilities (i.e. flexibility and delivery) are mutually supportive

in value co-creation scenario; Secondly, flexibility plays a primary role to amplify other capabilities in

the new strategy; Thirdly, the capabilities development follows a sequence of flexibility, delivery,

service and customerization. The findings of this study also enrich value co-creation studies by offering

proposed capabilities development pattern which facilitates strategists to operationize the concept of

value co-creation with customers and helps guide companies to take both upstream-focused and

downstream-focused views of capabilities development to excel in coming competition.

Crown Copyright & 2011 Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Firm’s competitive advantages are sustained by transformingresources into customer valued products, services and experiencesthrough various operational capabilities. The patterns of capabil-ities development determine operational contributions to thesuccess of a firm (Großler and Grubner, 2006; Flynn and Flynn,2004; Day, 1994). Traditionally, the established capabilities, suchas quality, delivery, cost and flexibility, are widely consideredinternally-built within company or between company and suppli-ers, thus an upstream-focused view of capabilities development.

However, the traditional upstream-focused view may ignore apotentially important source of capabilities development: theknowledge and skills embodied in a firm’s customer base(Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004; Zhang and Chen, 2008). Intheir empirical study, Zhang and Chen (2008) identify service andcustomerization as new capabilities in value co-creation system.They find that firms that can succeed in integrating customers for

011 Published by Elsevier B.V. All

).

value co-creation in downstream value chain can leverage custo-mer resources and develop new capabilities.

When adding new capabilities to a well-established base ofcapabilities, the patterns of capabilities development becomecomplicated. One opinion is that the newly developed capabilitiesmay conflict with the established ones as they may compete forthe scarce resources and detract management attention. In con-trast, the cumulative theory suggests that capabilities do notnecessarily conflict; instead they are mutually enhanced.However, few studies test the accumulation effect when addingnew capabilities.

Do the capabilities mutually reinforce or offset each other invalue co-creation situation? The answer to this question is crucialas it concerns the optimal path selection of capabilities develop-ment. Owing to the focus of this study, the above issues will notbe repeatedly tested in an upstream-focused condition. Instead,this study aims to examine the patterns of capabilities develop-ment in value co-creation with customers by considering bothtraditional capabilities and newly developed capabilities in a fastdeveloping economy, such as that in China.

Without such examination, neither is the relationship amongthe capabilities as mutual enhancement or conflict clear, nor can

rights reserved.

X. Zhang et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130 123

one expect to apply the relevant theory to offer guidance forlong-term lasting success in the value co-creating strategy. Somanagers might hardly develop a proactive approach with aprimary emphasis on the patterns of capabilities development.With a new paradigm of co-creation emerging (Zhang and Chen,2008; Parahalad and Ramaswamy, 2004), it is necessary to testand extend the theory in the new setting.

In doing so, this study firstly reviews related literature anddevelops relevant research hypotheses. Next, the article describesthe research design and methodologies. Based on the datacollected at 188 Chinese firms, this study presents the results ofanalysis. The article concludes by discussing the implications andsummarizing the contributions.

2. Research background and hypotheses development

2.1. Traditional theories of capabilities development

The development of capabilities means the mutual enhance-ment, offset or abandonment of various capabilities. Whenexplaining the patterns of capabilities development, two majortheories emerge: the trade-off theory and the cumulative theory.Both trade-off theory and cumulative theory acknowledge thenecessity of capabilities coordination, however, with differentemphases on how the capabilities coordinate.

The trade-off theory (Skinner, 1969, 1974) suggests thatcompany improving one capability is normally at the expense ofother capabilities (Slack, 1994). For example, Boyer and Lewis(2002) find evidences from managers, who make tradeoffs amongcompetitive capabilities. Wang and Masini (2009) find thatdevelopment of volume flexibility significantly increased operat-ing costs and deteriorated on-time delivery performance. Theydefine service flexibility as variations in the volume of output(Wang and Masini, 2009, p. 7). Their focus is to examine theimpact of service flexibility improvement on quality, on-timedelivery and cost when flexibility is developed after the latterthree capabilities are consolidated, which differs from the focus ofthis study. Recently, researchers suggested that trade-off theoryshall be observed in an environment, where firms are on or closeto the performance frontier. For more details of discuss-ion, readers are referred to a meta-review by Rosenzweig andEaston (2010).

In contrast, the applications of just-in-time and total qualitymanagement principles are in favor of the simultaneous improve-ment in cost, quality and delivery (Schonberger, 1986; Collins andSchmenner, 1993; Schmenner and Swink, 1998; Flynn et al.,1999). Many empirical studies provide further evidences thatimprovement in certain capabilities is not necessarily at the costof others (Cleveland et al., 1989; Roth and Miller, 1992; Vickeryet al., 1993; Rosenzweig and Roth, 2004; Flynn and Flynn, 2004;Großler and Grubner, 2006; Amoako-Gyampah and Meredith,2007; Lo et al., 2009; Paiva, 2010; Furlan et al., 2010). This kindof strategy to make simultaneously improvement in capabilitiesrefers to cumulative theory.

Cumulative theory, which is alternatively called capabilitiesprogression (Narasimhan et al., 2005; Rosenzweig and Roth,2004), is a multi-focused strategy and is verified through empiri-cal study by a number of researchers from perspectives ofcompany and suppliers (to name a few, Amoako-Gyampah andMeredith, 2007; Großler and Grubner, 2006; Flynn and Flynn,2004, 2005; Schmenner and Swink, 1998; Ferdows and de Meyer,1990). In general, the common agreement of cumulative theory ison the mutual reinforcement of capabilities, including quality,cost, delivery and flexibility (Nakene, 1986; Ferdows and DeMeyer, 1990; Noble, 1995; Flynn and Flynn, 2004; Großler and

Grubner, 2006). This view further lays out two important themes:the sequence of capabilities development and the identification ofprimary capability.

The sequence places priorities in capabilities development.An early sequence of capabilities development is quality, deliv-ery dependability, cost and flexibility, which is proposed byNakene (1986) and tested by Noble (1995). Although concurringwith mutual enhancement, later studies provide diversifiedresults and are not in compliance with the early proposedsequence. For example, Großler and Grubner (2006) show areverse direction that delivery capabilities have a direct impacton flexibility capabilities, contrasting to previous findingsthat improvement in flexibility has a direct positive impact ondelivery (including fast delivery and dependable delivery),see White (1996). When simultaneously considering quality, cost,delivery and flexibility capabilities, Amoako-Gyampah andMeredith (2007) display a non-significant coefficient (the stan-dardized b¼0.14). Different sequences will lead to differentpriorities in capabilities development, which prompts a necessityto investigate an optimal sequence in value co-creation scenario.

The identification of primary capability is also an importanttheme. The rationale is that an improvement in primary cap-ability will lead to simultaneous improvement in other capabil-ities. Normally, the starting point of the sequential developmentis the primary capability. For example, improvement in qualitycan amplify certain other capabilities when quality is primary(Schmenner and Swink, 1998; Ferdows and de Meyer, 1990).However, the primary capabilities differ in different scenarios.Flynn and Flynn (2004) find that dependability and speed areprimary for German plants whereas dependability and flexibi-lity are primary for American plants. Amoako-Gyampah andMeredith (2007) note that the primary capabilities are qualityfollowed by cost in Ghanaian firms. These differences reflect thecontingent attribute of the primary capability. Considering itsimportance in amplifying other capabilities, this study willexamine the primary capability in a setting of value co-creationstrategy.

Although previous studies on cumulative theory differ invarious aspects, it does not take away from the central conclusionthat mutually enhancement is the pattern of development inestablished capabilities when firms are not on or near theperformance frontier. An interesting issue here is if one shouldexpect to find similar strong relationships when adding newcapabilities in a different setting, such as value co-creationscenario, and in a different economic environment, such as thatof China, where firms would generally be expected to experiencefast and big changes.

2.2. The scenario of customer participation and value co-creation

in China

China is the largest emerging economy in the world and hassustained average economic growth of more than 9.5% for threedecades. Concurrently, Chinese consumers are one of the mostactive purchase groups in the world. On one side, consumptionmarket is dominated by private consumers, who come to paymore attention to satisfy their own individual demand at reason-able price. On the other side, the advance and popularity ofinternet and other technologies facilitate Chinese consumerspartake operations that are previously privileged by the company.Some subtle companies have already found the benefits ofco-creating value with customers.

For example, in Shanghai at Changle Road, Shan’xi Nan Road,Qibao Old Street and alike, many local garment shops benefitfrom design-by-yourself sackcloth costume as customers are wildabout such kind of customization. In Suzhou, Kinglong United

X. Zhang et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130124

Automotive Industry (suzhou) Co., Ltd. takes advantages ofcustomer on-site supervision to improve the quality for years.In Beijing, highly satisfied customers pasted their happy experi-ences on blogs after they visited the assembly line at BeijingHyundai Motor Company Corporation. Beijing Hyundai has beenworking with dealers to use the tactics for years to provide theircustomers additional experiences.

There are more companies that come to cater for these newchanges in demand. Systematically involving customers for valueco-creation in turn helps develop new capabilities as empiricallyevidenced in Zhang and Chen (2008). Whether the sustainment ofnew capabilities is at the cost of established ones? What is anoptimal sequence of capabilities development for new comers? Inessence, to withstand and succeed in the Chinese market, bothdomestic and foreign firms have to choose appropriate capabil-ities development pattern to achieve their own operationalsuccess. Given the flourish demand and uncertainties in themarket place, China provides an ideal laboratory to examine thepattern of capabilities development in value co-creation scenario.

2.3. Capabilities in value co-creation with customers and research

hypotheses development

To cope with the fast changing market and the stiff competi-tion, firms enhance flexibility and delivery capability to producethe customized products and services. However, this strat-egy does not guarantee sustainable competitive advantages(Vandermerwe, 2000; Pine et al., 1995; Pine, 1993). The problemis that products and services are too easy for competitors toemulate and can only lead to a short time gain (Deighton andBlattberg, 1996; Vandermerwe, 2000). Hence the customizedproducts and services cannot retain all time success for compa-nies (Pine et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2007).

The key is to integrate and involve customers in the valuecreation process (Pine et al., 1995; Wind and Rangaswamy, 2001;Zhang and Chen, 2006, 2008; Ramaswamy, 2009) as the utmostgoal is to continuously satisfy customers demand. The mostrecent cross-sectional research adds more weights on the co-creation strategy that the world’s leading organizations usedengagement of their customers as a primary strategy to gainbusiness success: those that engage their customers outper-formed those that did not (Gallup, 2009).

The engagement strategy of value co-creation with customersis coined customerization (Wind and Rangaswamy, 2001).Customerization combines mass customization and elicitation ofindividual customer demand information by involving customers,and is regarded as the next generation of mass customization(Pine et al., 1995; Wind and Rangaswamy, 2001). In contrastto mass customization, customerization encompasses moreco-creating activities and offers customers more controls in thecustomization process, which in turn helps develop and enhancethe operational capabilities (Wind and Rangaswamy, 2001;Zhang and Chen, 2008). Characterized as a customer-centeredstrategy, customerization develops and outstands two differentcapabilities: service capability and customerization capability(Zhang and Chen, 2008). In addition, Yeh et al. (2000) and Windand Rangaswamy (2001) also emphasize the roles of flexibilityand delivery when implementing customerization strategy.

2.3.1. Flexibility

The integration of customers for value co-creation requiresfrequent coordination owing to the related uncertainty and thehigh dependence on information. Flexibility is required due to avariety of customer needs, technology advancement as well asincreasing competition in the market place (De Meyer et al., 1989).

Flexibility is the capability to cope with uncertainty and to providethe customized products to satisfy customers’ specifications basedon the difficult-to-imitate learning experiences, skills, and knowl-edge in the process (Andreu and Ciborra, 1996).

Flexibility is a primary capability in value co-creation systemfor building up other capabilities, such as service capability anddelivery capability. In customerization, different customers mayhave very different individual demands. To satisfy the demands,firms have to develop the most appropriate product or servicefrom innumerous combinations of parts and components, whichplaces the requirement of higher flexibility. Also to involvecustomers from multiple channels means a high involvementstructure (Youngdahl, 1996), which places a requirement thatorganizations should equip with flexibility to response to such ahigh involvement structure (Prahalad and Ramaswamy, 2000).

2.3.2. Flexibility-service

Higher flexibility will help build service capability. Servicerefers to the ability to provide customized service during valueco-creation with customers (Zhang and Chen, 2008). Good serviceadds value to the physical product (Vickery et al., 2003) andprovides additional weights for companies to differentiate theirofferings from competitors (Pine et al., 1995). In customerization,the interactions between customers and firm along the customerparticipatory chain (Zhang and Chen, 2006) enable firm to createnew and value-adding service offerings together with the uniqueservice experiences for customers (Zhang and Chen, 2008).The building of service capability shall be very flexibly adaptableto the customer’s individual requirements (Yee et al., 2011).Flexibility provides a basis to support better service promise bybeing capable of quick responses in adjusting capacity, switchingproduction line, changing design and making mass customizedofferings. In other words, service capability provides customer’sutility by increasing the perceived value through interactionwhile flexibility is the enabler to help realize such promise bylinking the functional characteristics of products to the satisfac-tion of customer’s personal experience. In addition, the produc-tion and consumption of service is integrated when involvingcustomers. Such involvement which may bring uncertainty has totake advantage of flexible mass customization system whereflexibility is inherently required. Hence flexibility is emphasizedin order to provide basic support for service development. Theabove analysis leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1. Flexibility is positively associated with servicecapability.

2.3.3. Flexibility-delivery

Flexibility will help improve delivery capability. The relativelong delivery time in customization is often due to the informa-tion distortion and resources wasting (including time wasting) inthe process. In contrast to the traditional way that differentfunctional departments handle different tasks in a fixed order toadd value, in co-creation system, the company becomes a hub ofvalue creation grid with high flexibility. The sequential course ofthe traditional value chain becomes compressed in both time andplace, the process overlaps, and the value-creating activities occursimultaneously (Wikstrom, 1996). Such flexibility allows firm tomake faster response to the changing demands of customers.Flexibility helps redesign the operations and logistics, leading toprocesses that result in better, cheaper, and faster products andservices for customers (Wind and Rangaswamy, 2001). In custo-merization strategy, the improvement of flexibility to delivery cancome to an extreme that once customers bring forward theirpersonalized demands, the firm can immediately turn relevantresources into the required products, service or experiences using

Table 1Demographic information of sample.

Industry Frequency Percent

General manufacturing 66 35.11

Chemical and miscellaneous products 33 17.55

Electronic and electric equipment 24 12.77

Other manufacturing 22 11.70

Telecommunication and related 19 10.11

Transportation and vehicle manufacturing 13 6.91

Others 7 3.72

Missing 4 2.13

Total 188 100

X. Zhang et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130 125

flexible capability, thus realizing instant customerization forcustomers and shortening the delivery lead time (Yeh et al.,2000). This is because company can learn customers’ demandsfrom multi-aspect and continuously convey customer knowledgeto the customized offerings through flexibility. The literature alsoprovides empirical evidences that flexibility has significant posi-tive association to delivery capability (White, 1996). The aboveanalysis leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2. Flexibility is positively associated with deliverycapability.

2.3.4. Fexibility-customerization

Firm with higher flexibility may help enhance customerizationcapability in many ways. Flexibility can meet customers’ diversedemands, thus helping reduce the negative impacts of demandchanges and capacity fluctuation. This makes the firm able toutilize the critical resources to produce exactly what customerswant and to precisely target customer groups. Flexibility alsomeans quick response to the customer demand changes, whichmay require adjustment in product configuration, deliveryvolume, or design changes by frequent communication withcompanies. In co-creation process, flexibility provides firm agilityto only make the products that customers want through commu-nication with customers (Zhang and Chen, 2008; Ramaswamy,2009). This makes flexibility a critical route to customerization(Wind and Rangaswamy, 2001). The above analysis leads to thefollowing hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3. Flexibility is positively associated with customer-ization capability.

2.3.5. Service-customerization

When a firm is able to elicit demand information from acustomer about her specific needs and preferences using custo-mized service, the firm is able to use more detailed feedbacks tofind the best products or services for the customer (Pine et al.,1995). A company that succeeds in enhancing service capabilitiesin customerization will have more opportunities to gain anadvantage over its rivals because it represents an enormouschance for the company to cater to customers’ individual pre-ferences and improve system capabilities (Pine et al., 1995). Thisin return enables the firm to precisely target customer groups andincrease collaboration with customers (Yee et al., 2011). Hencethe emphasis of service capability will enhance firm’s customer-ization capability. The recent empirical results also support thefollowing hypothesis (Zhang and Chen, 2008). The above analysisleads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4. Service capability is positively associated withcustomerization capability.

2.3.6. Delivery-customerization

Good delivery capability will help enhance customerizationcapability. In the new strategy, the changes in customers’demands are quicker than those in traditional business processeswhere material products are created. And customers often expectall customized offerings can be finished immediately. To satisfythe demanding and impatient customers, firms with betterdelivery capability may have more advantages. Both quickdelivery and on time delivery of finished products increasecustomer satisfaction, as these are also exactly what customerswant. Besides, shortening delivery time makes the customizedofferings more attractive to the customers. In this sense, deliverycapability helps increase customers satisfaction which may inturn help increase collaboration with customers for potentialbusiness opportunities. The above analysis leads to the followinghypothesis.

Hypothesis 5. Delivery capability is positively associated withcustomerization capability.

3. Research design and methodologies

This study focused on the mechanisms of the cumulativecapabilities when involving customers for value co-creation.A range of firms from various industries and places in the middleof China were sampled in order to achieve a reasonable level ofexternal validity and generalizability. The target respondents hadaverage job experiences of 5.58 years in their companies. Theaverage departments they worked were 2.1. The respondents hadthe job titles of corporate presidents (14.0%), department man-agers (42.2%), section chiefs (23.4%), group leaders (6.2%) andothers (14.1%). About 79.6% of the target respondents hadmanagement positions that may help to provide more reliableinformation (Phillips, 1981). These also provided us with thebelief that they possessed a necessary degree of knowledgeregarding customer interactions and operational capabilities oftheir organizations. The demographic information of the sample isshown in Table 1.

All items were initially derived from relevant literature. Multi-item was developed for each construct in order to make betterdistinctions among respondents over the use of single item(Van Bruggen et al., 2002). Competitive capabilities have beendefined as the firm’s actual, or realized competitive strengths inits target markets (Rosenzweig and Roth, 2004, p. 354). The itemsthat measured the customerization capability and service cap-ability were taken from Zhang and Chen (2008, 2006). The itemsthat measured the flexibility and delivery capability were devel-oped based on Miller and Roth (1994). The latter items werewidely used in the literature. The respondents were asked tomake comparison with their major competitors, where 1: muchlower than the industrial average and 5: much higher than theindustrial average.

During pre-pilot study, the theoretical constructs and relevantitems were checked for the content validity. Then in the pilotstudy, the items were firstly purified using corrected item-totalcorrelation, and secondly the unidimensionality were assessedusing exploratory factory analysis with varimax rotation andprincipal components extraction. In the large-scale survey, theintraclass correlation was calculated. All results were above 0.5,indicating an acceptable inter-rater agreement.

In the large-scale survey, 300 companies located in the mid-China were randomly selected from the alumni of the authors’schools. The reasons for this sampling were that (1) most of thesurveyed respondents had years of management experienceswhich ensured that the respondents knew the situation ofcustomer–firm interaction at their own company; (2) the samplecovered wide industries that helped generalize the researchresults and (3) the respondents had a relatively high respondingrate. The respondents were either called and then sent through

X. Zhang et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130126

E-mail the questionnaires or directly distributed the question-naires when they were attending at the universities. Question-naires were received in two stages. In the first stage, 118questionnaires received, among which 113 were valid. In thesecond stage, 91 questionnaires received among which 75 werevalid. Thus, the total 188 valid questionnaires represented aneffective responding rate of 62.7%.

This study also examined the common method biases (CMVs)(Lindell and Whitney, 2001; Podsakoff et al., 2003; Malhotra et al.,2006) as the measures were originally used for single respondentin relevant literature. Among the four sources of CMVs (Podsakoffet al., 2003), measurement context effects might be the mainconcern in this study. Because the items examined few social orpolitical issues about which people could often have very strongviews. As such, the common rater effects were not likely the issuein this study. Also the questions were developed to measure thespecific capabilities in value co-creation system. After the refine-ment of the questions in the pre-pilot study and in the pilot study,respondents easily knew what the researchers were actuallyasking. In comparison with other disciplines like education andpsychology, the questions in this study were not the abstract onessuch as human emotions. Hence the item characteristic effectswere not likely the issue in this study. Also the questions, whichremained short, could hardly lead to respondents fatigue. Hencethe item context effects were not likely the issue either.

Measurement context effects were examined using the mar-ker-variable technique to assess the CMV because the HSF test haslimitations and is known to be highly conservative (Podsakoffet al., 2003; Malhotra et al., 2006). The marker-variable techniquecan be implemented in both a priori fashion and a post-hocfashion. This study used a post-hoc fashion to assess the CMV asproposed in Lindell and Whitney (2001) and Malhotra et al.(2006). In a post-hoc fashion, although the smallest positive valueof the correlation among the manifest variables would be areasonable representation for CMV, the second-smallest positivecorrelation, rM2, as a more conservative estimate is advocated,because the smallest correlation is possibly capitalized by chancefactor (Lindell and Whitney, 2001). In this study, the second-smallest correlation, rM2,was 0.12. For factor correlation calcula-tion, according to Lindell and Whitney (2001) and Malhotraet al. (2006), the uncorrected estimate rU(Flex, SERV)¼0.815, theCMV-adjusted correlation rA(Flex, SERV)¼0.790 with t¼17.51;similarly, rU(Flex, Deli)¼0.725, rA(Flex, Deli)¼0.688 with t¼12.88,

Table 2Results of confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement model.

Items Standard loadings Standard errors

Flexibility-service

F1 0.685 0.075

F3 0.780 0.068

F4 0.696 0.072

S1 0.808 0.057

S2 0.865 0.041

S3 0.762 0.052

S4 0.873 0.043

w2/df¼20.784/13¼1.599, IFI¼0.989, RFI¼0.953, AGFI¼0.939, CFI¼0.989, RMSEA¼0.0

Delivery-customerization capability

D1 0.831 0.042

D2 0.906 0.037

D3 0.812 0.039

CC1 0.859 0.041

CC2 0.798 0.042

CC3 0.791 0.054

CC4 0.741 0.065

w2/df¼19.088/13¼1.468, IFI¼0.992, RFI¼0.962, AGFI¼0.946, CFI¼0.992, RMSEA¼0.0

rU(Flex, CC)¼0.814, rA(Flex, CC)¼0.789 with t¼17.45, rU(SERV, CC)¼

0.798, rA(SERV, CC)¼0.770 with t¼16.44, rU(Deli, CC)¼0.687, rA(Deli, CC)¼

0.644 with t¼11.46, rU(Serv, Deli)¼0.592, rA(Serv, Deli)¼0.536 witht¼8.64. Taking together the results of the test, the CMV did notsubstantially bias the analysis in this study.

4. The results of analysis

The following set of criteria were used to assess the measure-ment properties of constructs: unidimensionality, convergentvalidity, discriminant validity (Venkatraman, 1989), Cronbach’salpha and composite reliability.

4.1. Unidimensionality assessment

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to examinethe associations between items and constructs specified a priori.This was accomplished by restricting the items to load on theirtheoretically specified constructs. With AMOS 7.0, the criteriafor fit measures recommended by Arbuckle (2006) andHau et al. (2004) were used, as listed in Table 2. The results offactor analysis were satisfied with these criteria, which providedevidences of unidimensionality.

4.2. Convergent validity assessment

In convergent validity assessment, a construct with a relia-bility value of at least 0.50 and a significant critical ratio forloading is considered to be desirable (Gerbing and Anderson,1988). In addition, a good measurement model fit of constructsrequire the relevant fit indices be above 0.90, all l coefficients beabove 0.50 and significant, and the model need not be significant(Arbuckle, 2006; Hau et al., 2004). The results of analysisindicated that the measurement models of the constructs fittedthe data well and the items of the constructs in the modelachieved convergent validity, as shown in Table 2.

4.3. Discriminant validity assessment

Discriminant validity was assessed by evaluating the w2 differ-ence between constrained and unconstrained correlation models ofthe constructs. For change in one degree of freedom, the significant

Critical ratio Cronbach’s alpha/composite reliability

8.887 0.765/0.765

8.085

–

– 0.887/0.889

12.901

10.934

13.206

56

– 0.885/0.887

14.483

12.909

– 0.872/0.875

12.739

12.600

11.499

50

X. Zhang et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130 127

results of w2 differences indicate strong support for the discriminantvalidity (Venkatraman, 1989; Bagozzi and Yi, 1988; Gerbing andAnderson, 1988). With change of one degree of freedom, The Dw2 ofFlex-Deli pair was 30.436�6.31¼24.126 (Ddf¼9�8¼1), The Dw2

of Flex-Serv pair was 39.190�20.784¼18.406 (Ddf¼14�13¼1),the Dw2 of Flex-CC pair was 34.376�13.722¼20.654 (Ddf¼

14�13¼1), the Dw2 of Serv-CC pair was 35.663�22.614¼13.05 (Ddf¼20�19¼1), the Dw2 of Serv-Deli pair was 42.325�15.550¼26.78 (Ddf¼14�13¼1), the Dw2 of Deli-CC pair was43.632�19.088¼24.54 (Ddf¼14�13¼1), the w2 difference testsfor all 6 pairs of constructs were significant at po0.05.

4.4. Reliability

The reliabilities were measured using Cronbach’s alpha andcomposite reliabilities (Cronbach, 1951; Bagozzi and Yi, 1988).A Cronbach’s alpha 40.7 and composite reliability 40.6 aredesirable. The results listed in Table 2 indicated satisfactoryresults.

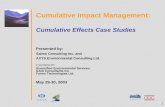

4.5. Structural model and hypotheses testing

The structural model shows paths between the exogenousfactors and the endogenous factors (see Fig. 1). The tests ofhypotheses were based on the paths in the structural model.A positive and significant coefficient provides supporting evidencesfor corresponding hypothesis. The structural model was evaluatedusing AMOS 7.0. The results were shown in Fig. 1. The indicesindicated an adequate fit for the structural portion of the model. Thew2 was 83.817, degree of freedom was 72, and the w2/df was 1.164,p¼0.161, CFI¼0.993, TLI(NNFI)¼0.991, GFI¼0.945, AGFI¼0.920,RMSEA¼0.029 (with low0.90¼0.000 and high0.90¼0.053).

The results of analysis generally provided supporting evi-dences for the Hypotheses 1–3. The path between flexibility andservice capability was positive and significant (the standardizedr¼0.816, po0.000). The results indicated that flexibility hadsignificant positive association with service capability, thus sup-porting Hypothesis 1. The path between flexibility and deliverycapability was positive and significant (the standardized r¼0.727,po0.000). The results indicated that flexibility had significantpositive association with delivery capability, thus supportingHypothesis 2. The path between flexibility and customerizationcapability was positive and significant (the standardized r¼0.344,p¼0.032). The results indicated that flexibility had significant

Flexibility

Delivery

F1

F2

F3

D1

D2

D3

Hr=0.816,

0.696

0.770

0.697

0.835

0.904

0.811

H2r=0.727, p<0.000

Hr=0.203,

Hr=0.344

Fig. 1. Analysis of structur

positive association with customerization capability, thus sup-porting Hypothesis 3. In addition, the relative larger standardizedcoefficients between flexibility and other capabilities providedthe empirical evidences that flexibility had stronger associationwith other capabilities could not be rejected. Putting together, theabove results provided supporting evidences that flexibility playsa primary role in amplifying other capabilities

Hypothesis 4 was also supported, which stated that servicecapability has significant positive association to customerizationcapability. The relevant path coefficient was positive and signifi-cant (the standardized r¼0.396, p¼0.001). Hypothesis 5, whichstated that delivery capability had significant positive associationwith customerization capability, was weakly supported. Therelevant path was positive and weakly significantly (the standar-dized b¼0.203, p¼0.026).

5. Discussion and conclusions

The findings of this study are in favor of mutual enhancementeffect when adding new capabilities in value co-creation system.Based on the findings, this study contributes to the literature bypresenting the capabilities development pattern which can besummarized in the following three aspects. First, new capabilities(i.e. service and customerization) and established capabilities(i.e. flexibility and delivery) are mutually supportive. As evi-denced in the results of analysis in Section 4, all path coefficientswere positive and significant. It also meant no trade-off effect wasfound in the value co-creation scenario. Second, the findings ofthis study suggest that flexibility is in the basic position toamplify other capabilities. The coefficients between flexibilityand other capabilities which have relatively higher values thanthose of other capabilities provided the empirical evidences, asshown in Fig. 1. Third, the development follows a sequence offlexibility, delivery, service and customerization in value co-creation scenario. All hypotheses could not be rejected as perthe results of analysis in Section 4.

The above contributions were achieved by identifying andtesting five research hypotheses in the scenario of value co-creation with customers, using data collected at 188 companiesin the middle of China. The measures satisfied key measurementcriteria, including unidimensionality, convergent validity, discri-minant validity and reliabilities as presented in Section 4.

Service

Customerization

S1

S2

S3

C1

C2

C3

C4

1p<0.000

0.804

0.844

0.747

0.850

0.803

0.802

0.735

5 p=0.026

H4r=0.396, p=0.001

3, p=0.032

S3

0.866

al equation modeling.

X. Zhang et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130128

Furthermore, all coefficients between the measured capabilitieswere positive and significant, as shown in Fig. 1.

For cumulative theory, this study contributed importantempirical evidence regarding the development pattern whenadding new capabilities. As noted by Rosenzweig and Easton(2010) and White (1996), although the relevant theories offered abroad array of possible competitive dimensions, the majority ofresearch focused on the established capabilities, i.e., quality,delivery, flexibility and cost (Skinner, 1969, 1996; Ferdows andDe Meyer, 1990; Miller and Roth, 1994; Boyer and Lewis, 2002;Rosenzweig and Easton, 2010). In fact, the law of cumulativecapabilities not only emphasizes the mutual enhancement effectamong established capabilities, but also outstands the features ofprogression (Ferdows and De Meyer, 1990; Rosenzweig andEaston, 2010) which include both improvement of later estab-lished capabilities on the previously consolidated ones, and newcapabilities on the established base. For example, Wang andMasini (2009) belongs to the former as their focus is to examinethe impact of service flexibility improvement on quality, on-timedelivery and cost when flexibility is developed after the latterthree capabilities are consolidated. This study is categorized intothe latter as the focus is to examine the development patternwhen adding service and customerization on an established base.Obviously, more studies should be carried out in a real cumulativesense as both above directions are significant complementaritiesto present theories.

The findings that Chinese firms can develop new capabilitiesand sustain mutually supportive effect between new and estab-lished capabilities are consistent with present literature. Compe-titive dimensions in terms of capabilities (Miller and Roth, 1994)are often reshaped by changing customer demand (Hill, 2000).The flourishing but changing demands faced by Chinese firmscould be the driven force to develop new capabilities and sustainestablished ones in value co-creation scenario. Meantime, accord-ing to performance frontier theory (Schmenner and Swink, 1998;Clark, 1996; Porter, 1996), the results of positive correlations andmutual enhancement are expected. It implies that there is stilllarge space for improvement at the sampled companies as long asthe overall performance of a majority of sampled companies isnot positioned close to the performance frontier (Schmenner andSwink, 1998; Rosenzweig and Easton, 2010).

The findings that flexibility is in the basic position to amplifyother capabilities in the value co-creation scenario supplementcontingency nature of the primary capability to the presentliterature. The previously indentified primary capabilities includequality (see for example, Amoako-Gyampah and Meredith, 2007;Schmenner and Swink, 1998; Ferdows and de Meyer, 1990),dependability and speed for German plants and dependabilityand flexibility for American plants (Flynn and Flynn, 2004).Different development stages may contribute to these differencesin primary capabilities (cf. Rosenzweig and Easton, 2010). As DeMeyer et al. (1989) noted that Japanese firms were moving onflexibility because they had already reached prerequisite level ofquality, dependability and cost efficiency sequentially over time.Different from the above development stage factor, flexibilityidentified as a primary capability in this study evidences that thevalue co-creation strategy (or perhaps other specific strategies,e.g. co-design strategy) can be another possible contingent factor.

This study suggests a sequence of flexibility, delivery, serviceand customerization to build cumulative capabilities in value co-creation strategy. The sequence not only means a prescribedbottom-up order of development from primary capability to highlevel ones, but also a top-down view of inter-linked relationshipamong capabilities. As Noble (1995, p. 696) notes ‘‘y to addressone capability, it is necessary to build up all of the underlyingcapabilities as well.’’ The utmost underlying capability is the

primary capability. Hence the differences in development sequ-ence are related to the different primary capabilities identified.This refers to dynamic nature incorporated in capabilities. How-ever, most of the studies are static in nature due to the difficultiesto collect objective data and to capture the longitudinal dynamics.Although difficult to manage, it is an attractive future researchdirection.

The findings of this study enrich value co-creation studies byoffering proposed capabilities development pattern whichfacilitates strategists to operationize the concept of value co-creation with customers. To continuously satisfy customersdemand in product, service and experiences (Pine et al., 1995;Wind and Rangaswamy, 2001; Zhang and Chen, 2006, 2008;Ramaswamy, 2009), firms need to develop necessary capabilitiesto transform relevant resources, including customer resources,into the expected outputs. Zhang and Chen (2008) identify newcapabilities in the strategy of value co-creation with customers.This study further extends their work by linking the newcapabilities to an established base. The capabilities developmentpattern summarized in this study makes the co-creation strategymore attractive and more sustainable as the co-creation strategycan follow a pre-specified way which is supported by relevantcapabilities in a mutually supportive manner.

Customers do not determine corporate strategy, but theirvalues and expectations have influence on the company’s strat-egy. Value co-creation with customers is an increasingly impor-tant strategy for firms to sustain and excel in competition. Tosuccessfully implement the strategy, capabilities development iscritical. Many practitioners in operations management are notclear about the impacts of customer participation, making thecustomization process more passive and resulting in worrisomeof the capabilities development. The findings of this study helpguide practitioners to follow a logic pattern to develop capabil-ities when involving customers for co-creating value, thus havingimportant implications for practitioners.

First, from a downstream capabilities development perspec-tive, firms can integrate customers for value co-creation to makeimprovement. Such downstream capabilities development per-spective does not isolate from the previous perspective. Instead,the new capabilities developed in value co-creation with custo-mers are linked to the established ones with mutual enhance-ment effect. Such a mutual enhancement effect of capabilitiesitself is another enlarged value co-created with customers. Hencefirms in emerging market can proactively take both upstream anddownstream focused views to build up capabilities.

Second, the capabilities development and resources allocationshall be better focused on the primary capability and follow thesequence of flexibility, delivery, service and customerization tobuild cumulative and lasting capabilities in value co-creationstrategy. That means the amplification of new capabilities isdependent on the underlying flexibility. Hence flexibility shallreach a certain level before making efforts to improve service andother capabilities required in customerization. For majority ofcompanies in emerging economy, they can rely on traditionalcapabilities to compete in the new environment and can fur-ther develop and enhance the new capabilities in a pattern assuggested in this study.

There are also several limitations in the study. The samplemight differ from the national population although the use of thecross-sectional data helped maintain a broader coverage withrelatively high rate of return. Also the perceptual measures couldrepresent a limitation (Vokurka and O’Leary-Kelly, 2000), althougha major of studies used perceptual measures giving the difficultiesto obtain objective data (Rosenzweig and Easton, 2010). Whilethere was no readily apparent bias in terms of the range ofrespondents, the potential for sample and measurement biases

Table A1Items and measurement properties.

Sources Coding Mean S.D.

Miller and Roth, 1994 F1 The ability to adjust capacity rapidly 3.36 1.06

a¼0.780 F2n The ability to provide multi-type products and services 3.66 1.05

F3 The ability to make design changes 3.35 1.06

F4 The ability to provide customized products at cost near mass production 3.23 1.05

Miller and Roth, 1994 D1 The ability to deliver product quickly 3.41 0.99

a¼0.873 D2 The ability to deliver product on time 3.56 0.99

D3 The ability to shorten the delivery lead time 3.32 0.94

Zhang and Chen, 2006, 2008 S1 The ability to create new service 3.34 1.11

a¼0.88 2 S2 The ability to provide unique service experience 3.17 1.02

S3 The ability to provide multi-kind service 3.23 1.00

S4 The ability to provide customized value-adding service 3.25 1.08

Zhang and Chen, 2006, 2008 CC1 Precisely target customer groups 3.50 0.99

a¼0.863 CC2 Provide exactly what customers want 3.48 0.94

CC3 Identify more market opportunities 3.51 1.05

CC4 Increase collaboration with customers 3.33 1.09

n F2 was not entered into the final model due to the error correlation in the analysis.

X. Zhang et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130 129

does represent a minor limitation. To go around this limitation andcontrol the method bias by self-reporting, the empirical study wascarried out based on multi-item constructs and carefully designedmeasurement. Thus the potential problem was controlled in theminimum and the limitation did not seriously bias the researchresults. This study examines only the development of the cap-abilities in value co-creation strategy, especially for those whichare concerned by customerization strategy. Future study can beconducted by incorporating more capabilities based on longitu-dinal data with consideration of the above limitations.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate one anonymous referee and the associateeditor, Prof. T.C. Edwin Cheng for their guidance and helpful com-ments. The first author acknowledges the support by National NaturalScience Foundation of China No. 70972005 and the Humanities andSocial Sciences Research Funds for Young Scholars No. 08JC630007sponsored by the Ministry of Education.

Appendix

See Table A1 for more details.

References

Amoako-Gyampah, K., Meredith, J.R., 2007. Examining cumulative capabilities in adeveloping economy. International Journal of Operations and ProductionManagement 27 (9), 928–950.

Andreu, R., Ciborra, C., 1996. Organizational learning and core capabilities devel-opment: the role of IT. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 5 (2),111–127.

Arbuckle, J.L., 2006. AMOSTM 7.0 User’s Guide. Amos Development Corporation,Spring House, PA, U.S.A.

Bagozzi, R.P., Yi, Y., 1988. On the evaluation of structural equation models.Academy of Marketing Science Journal 16 (1), 74–94.

Boyer, K.K., Lewis, M., 2002. Competitive priorities: investigating the need fortradeoffs in operations strategy. Production and Operations Management 11(1), 9–20.

Clark, K., 1996. Competing through manufacturing and the new manufacturingparadigm: is manufacturing strategy passe? Production and OperationsManagement 5 (10), 42–58.

Cleveland, G., Schroeder, R.G., Anderson, J.C., 1989. A theory of productioncompetence. Decision Sciences 20 (4), 655–688.

Collins, R.S., Schmenner, R.W., 1993. Achieving rigid flexibility: factory focus forthe 1990s. European Management Journal 11 (4), 443–447.

Cronbach, L.J., 1951. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psycho-metrika 16 (3), 297–334.

Day, G.S., 1994. The capabilities of market driven organizations. Journal ofMarketing 58 (4), 37–52.

De Meyer, A., Nakane, J., Miller, J.G., Ferdows, K., 1989. Flexibility: the nextcompetitive battle—the manufacturing futures survey. Strategic ManagementJournal 10 (2), 135–144.

Deighton, J., Blattberg, R., 1996. Manage marketing by the customer equity test.Harvard Business Review 74 (4), 136–144.

Ferdows, K., De Meyer, A., 1990. Lasting improvements in manufacturing perfor-mance: in search of a new theory. Journal of Operations Management 9 (2),168–184.

Flynn, B.B., Flynn, E.J., 2004. An exploratory study of the nature of cumulativecapabilities. Journal of Operations Management 22 (5), 439–457.

Flynn, B.B., Flynn, E.J., 2005. Synergies between supply chain management andquality management: emerging implications. International Journal of Produc-tion Research 43 (16), 3421–3436.

Flynn, B.B., Schroeder, R.G., Flynn, E.J., 1999. World class manufacturing: aninvestigation of Hayes and Wheelwright’s foundation. Journal of OperationsManagement 17 (3), 249–269.

Furlan, A., Pont, G.D., Vinelli, A., 2010. On the complementarity between internaland external just-in-time bundles to build and sustain high performancemanufacturing. International Journal of Production Economics. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.07.043.

Gallup. Customer Engagement: What’s Your Engagement Ratio? Gallup, Inc., 2009,available at /http://www.allegiance.com/documents/press/EconomicsofEngagement.pdfS.

Gerbing, D.W., Anderson, J.C., 1988. An updated paradigm for scale developmentincorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of MarketingResearch 25 (2), 186–192.

Großler, A., Grubner, A., 2006. An empirical model of the relationships betweenmanufacturing capabilities. International Journal of Operations and ProductionManagement 6 (5), 458–485.

Hau, K.T., Wen, Z.L., Cheng, Z.J., 2004. Structural Equation Model and Its Applica-tions. Educational Science Publishing House (in Chinese), Beijing, China.

Hill, T., 2000. Manufacturing Strategy: Text and Cases, 2nd edition Palgrave,Basingstoke, United Kingdom.

Lindell, M.K., Whitney, D.J., 2001. Accounting for common method variance incross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (1),114–121.

Lo, C.K.Y., Yeung, A.C.L., Cheng, T.C.E., 2009. ISO 9000 and supply chain efficiency:empirical evidence on inventory and account receivable days. InternationalJournal of Production Economics 118 (2), 367–374.

Malhotra, N.K., Kim, S.S., Patil, A., 2006. Common method variance in IS research:a comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research.Management Science 52 (12), 1865–1883.

Miller, J.G., Roth, A.V., 1994. A taxonomy of manufacturing strategies. Manage-ment Science 40 (3), 285–304.

Nakene, J., 1986. Manufacturing Future Survey in Japan: A Comparative Survey1983–1986. Tokyo, Wesda University, System Science Institute.

Narasimhan, R., Swink, M., Kim, S.W., 2005. An exploratory study of manufacturingpractice and performance interrelationships: implications for capability pro-gression. International Journal of Operations and Production Management25 (10), 1013–1033.

Noble, M., 1995. Manufacturing strategy: testing the cumulative model in amultiple country context. Decision Sciences 25 (5), 693–721.

Paiva, E.L., 2010. Manufacturing and marketing integration from accumulativecapabilities perspective. International Journal of Production Economics126 (2), 379–386.

X. Zhang et al. / Int. J. Production Economics 132 (2011) 122–130130

Phillips, L.W., 1981. Assessing measurement error in key informant reports:a methodological note on organizational analysis in marketing. Journal ofMarketing Research 18 (4), 395–415.

Pine, B.J., 1993. Mass customizing products and services. Strategy and Leadership21 (4), 6–13 (55).

Pine, B.J., Peppers, D., Roggers, M., 1995. Do you want to keep your customersforever? Harvard Business Review 73 (2), 103–114.

Podsakoff, P.M., Mackenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., Podsakoff, N.P., 2003. Common methodbiases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recom-mended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5), 879–903.

Porter, M.E., 1996. What is strategy? Harvard Business Review 74 (6), 61–78.Prahalad, C.K., Ramaswamy, V., 2000. Co-opting customer competence. Harvard

Business Review 78 (1), 79–87.Prahalad, C.K., Ramaswamy, V., 2004. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating

Unique Value with Customers. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.Ramaswamy, V., 2009. Leading the transformation to co-creation of value. Strategy

and Leadership 37 (2), 32–37.Rosenzweig, E.D., Easton, G.S., 2010. Tradeoffs in manufacturing? A meta-analysis and

critique of the literature. Production and Operations Management 19 (2), 127–141.Rosenzweig, E.D., Roth, A.V., 2004. Towards a theory of competitive progression:

evidence from high-tech manufacturing. Production and Operations Manage-ment 13 (4), 354–368.

Roth, A., Miller, J.G., 1992. Success factors in manufacturing. Business Horizons 35(4), 73–81.

Schmenner, R.W., Swink, M.L., 1998. On theory in operations management. Journalof Operations Management 17 (1), 97–113.

Schonberger, R.J., 1986. World Class Manufacturing. Free Press, New York.Skinner, W., 1969. Manufacturing—missing link in corporate strategy. Harvard

Business Review 47 (3), 136–145.Skinner, W., 1974. The Focused factory. Harvard Business Review 52 (3), 113–121.Slack, N., 1994. The importance–performance matrix as determinant of improve-

ment priority. International Journal of Operations and Production Manage-ment 14 (5), 59–75.

Van Bruggen, G.H., Lilien, G.L., Kacker, M., 2002. Informants in organizationalmarketing research: why use multiple informants and how to aggregateresponses. Journal of Marketing Research 39 (4), 469–478.

Vandermerwe, S., 2000. How increasing value to customers improves businessresults. MIT Sloan Management Review 42 (1), 27–37.

Venkatraman, N., 1989. Strategic orientation of business enterprises: the construct,dimensionality, and measurement. Management Science 35 (8), 942–962.

Vickery, S.K., Droge, C., Markland, R.E., 1993. Production competence and businessstrategy: do they affect business performance. Decision Sciences 24 (2),435–455.

Vickery, S.K., Jayaram, J., Droge, C., Calantone, R., 2003. The effects of an integrativesupply chain strategy on customer service and financial performance: ananalysis of direct versus indirect relationships. Journal of Operations Manage-ment 21 (5), 523–539.

Vokurka, R.J., O’Leary-Kelly, S.W., 2000. A Review of empirical research onmanufacturing flexibility. Journal of Operations Management 18 (4), 485–501.

Wang, C., Masini, A., 2009. The Sand Cone model revisited: the impact of serviceflexibility on quality, delivery, and cost. Working paper, London BusinessSchool /http://mtei.epfl.ch/webdav/site/mtei/shared/mtei_seminars/2010/Wang_Masini_2009.pdfS.

White, G.P., 1996. A meta-analysis model of manufacturing capabilities. Journal ofOperations Management 14 (4), 315–331.

Wikstrom, S., 1996. The customers as co-producer. European Journal of Marketing30 (4), 6–19.

Wind, Y.J., Rangaswamy, A., 2001. Customerization: the next revolution in masscustomization. Journal of Interactive Marketing 15 (1), 13–32.

Yee, R.W.Y., Yeung, A.C.L., Cheng, T.C.E., 2011. The service-profit chain: anempirical analysis in high-contact service industries. International Journal ofProduction Economics 130 (2), 236–245.

Yeh, R.T., Pearlson, K.E., Kozmetsky, G., 2000. Zero Time: Providing InstantCustomer Value—Every Time, All the Time!. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

Youngdahl, W., 1996. An investigation of service-based manufacturing perfor-mance relationships. International Journal of Operations and ProductionManagement 16 (8), 29–43.

Zhang, X., Chen, R.Q., 2006. Customer participative chain: linking customers andfirm to co-create competitive advantages. Management Review (in Chinesewith English abstract) 18 (1), 51–56.

Zhang, X., Chen, R.Q., 2008. Examining the mechanism of the value co-creationwith customers. International Journal of Production Economics 116 (2),242–250.

Zhang, X., Chen, R.Q., Ma, Y., 2007. An empirical examination of response time,product variety and firm performance. International Journal of ProductionResearch 45 (14), 3135–3150.