Mothing in the Himalaya - V. P. Uniyalvpuniyal.com/images/mothing_himalaya.pdf3,000m) in the more...

Transcript of Mothing in the Himalaya - V. P. Uniyalvpuniyal.com/images/mothing_himalaya.pdf3,000m) in the more...

4 Antenna 2016: 40 (1)

Mothing in the Himalaya:No mountain too high

Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve.

Pritha Dey and V. P. Uniyal

Wildlife Institute of India, ChandrabaniDehradun- 248001, India

Contacts: [email protected]

The Himalayas never cease to enthrallus with their beauty, vastness andendemicity. The Western Himalayacovers the Kumaon-Garhwal, North-West Kashmir and North Pakistan.Biogeographically it lies in thetransition zone between the Palearcticand Indo-Malayan realms, so speciesfrom both the zones overlap. Thegeological, climatic and altitudinalvariations as well as physical structuralcomplexity contribute to the biologicaldiversity of the region. Thesemountains range from 500m asl (abovesea level) to more than 8000m aslgiving a range of ecosystems withinonly a couple of hundred kilometers.

Large parts of this unique ecosystemare under threat due to human impacts.The habitats for many species have apatchy distribution due to humanencroachment. The increasingpopulation in the region has led toextensive deforestation and the clearingof grasslands for cultivation. There is alarge-scale conversion of lands foragriculture and settlements.

Antenna 2016: 40 (1) 5

Atlas moth

Erebus sp. (Photo Abesh Sanyal)

6 Antenna 2016: 40 (1)

We studied the diversity patterns ofmoths in Nanda Devi BiosphereReserve, a Western Himalayanprotected area and a World HeritageSite. The area has the typical attributesof the larger Western Himalayan rangeand promised to provide us withstunning insights into the existingpatterns of biodiversity. Our researchon the altitudinal distribution of mothstook us to many villages within the areaof my study. The local tribe is theBhotiya who are mainly agro-pastoralists. There are about 19 villageswithin the protected area. We stayedwith them, spoke with them, and learnttheir ways and practically lived theirlives. Their hospitality and simplicitywas beyond our imagination.

Moths as bio-indicators:

Moths have always lagged behindbutterflies, being nocturnal, lessattractive and thus less studied. Wehave very little idea as to how manyspecies are endangered or even howmany exist. Moths are importantecologically as pollinators, herbivores,and prey for birds, but most recently asenvironmental indicators. Many studieshave established this group as potent

bio-indicators (Summerville et al.2003, Kitching et al. 2000).

Reading about these less-exploredtaxa, we were curious to know howthey would respond to rapid changes inenvironmental gradients and humanimpacts. The Western Himalayalandscape with its uniqueness gave usan array of conditions to study thesepatterns in moth diversity. I particularlychose one family of moths, theGeometridae family. This family alongwith Erebidae is the most specioseamong the moths. Geometrid mothshave shown interesting patterns inother high altitude areas and are moreabundant in high altitudes. The studyarea has four broad divisions of foresttypes viz. Temperate forests (2,000–2,800m), Subalpine forests (2,800–3,500m), Alpine scrublands(3800–4500m), Alpine meadows andmoraines (>4,500m) (Champion andSeth 1968).

The study area attracts many touristsas it is home to the highest gurudwarain India, the Hemkund Sahib(4,500m), Valley of Flowers NationalPark, and the Badrinath shrine. Sothousands of pilgrims and generaltourists come to Joshimath (the most

populated town within the protectedarea). The area surrounding Joshimathis highly modified by human activities,generated by the economic benefits oftourism but at higher altitudes othervillages are just hamlets nested withinforests. This generates a dramaticgradient of anthropogenic pressureswithin the region, which gives us anopportunity to study and understandthe response of moths as a groupsensitive to environmental andanthropomorphic change.

Our research:

Studying moths along the altitude was achallenge as working at night in themountains is not as easy or adventurousas it might seem. As we stayed in thevillages with the local people, they failedto understand why we would want toventure out at night in the forest tostudy some insect! They would stop us;warn us of evil spirits in the forest aswell as the Himalayan Black Bear (Ursusthibetanus) which might attack. Butnothing stopped us from completing thework and finally our determinationimpressed them, and few of the villagerseven volunteered to come along with usat night to help us out!

Western Himalayan Landscape, Garhwal.

Antenna 2016: 40 (1) 7

Eumelea sp. (Photo Abesh Sanyal)

Ginshachia sp. (Photo Abesh Sanyal)

8 Antenna 2016: 40 (1)

We studied two gradients of humandisturbance and forest types (Joshimathand Lata) to investigate the relationshipbetween the moths, the environmentand the human activity. We sampledmoths in the forests at dusk by settinglight traps which were operated for 3-4 hours; the moths were collectedmanually and documented withphotographs. We recorded themicrohabitat and other variables whichmight influence the presences orabsents of the moths. We sampledacross the available forest types atdifferent altitudes in order todetermine any patterns in diversity andspecies composition.

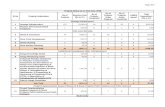

Moths belonging to the five mostdiverse families (Noctuidae,Geometridae, Arctiidae, Crambidae,Lymantriidae) were identified into

morphospecies. The familyGeometridae was the most abundant(Fig.1) at all the sites with over 700individuals recorded. The subfamilyEnnominae was most abundant at thelower altitudes while the higheraltitudes were dominated by thespecies belonging to the subfamilyLarentiinae. The Western Mixedconiferous forest (sub forest type undertemperate forests) showed themaximum species richness (Fig.2). Thenumber of morphospecies andindividuals at each of the trap siteswere negatively correlated withelevation and temperature. The speciesdiversity (alpha diversity) showed adifferential response to vegetationstructure on the two mountain slopeswith a mid-elevation peak (2,300-3,000m) in the more disturbed

gradient in Joshimath. Interestingly, theforest types had a greater effect ondiversity on the more disturbedmountain slopes.

Family Geometridae with such highabundance can be studied for long-term as indicative of environmentalchanges.

Our results indicate that resourcediversity plays an important role inmaintaining species diversity. Theseresults predict negative impacts for anyongoing extraction of forest resourceson moth diversity and the ecosystemservices they deliver. It also highlightsthe role that moths can play inmonitoring climatic andanthropomorphic changes in foreststructure.

The study on moths in high altitudelandscapes can provide a much-neededinsight into their endemic diversity.Monitoring insect populations is oftena difficult task for the managers ofprotected areas. So we hope this studywill make the these managers moreaware of the importance of mothspecies and also hope it will play a rolein shaping future managementprograms for the conservation of thehabitats of the rare species bycontrolled grazing and limiting resourceextraction by local people.

ReferencesChampion, H.G. and Seth, S.K. 1968. A

revised survey of forest types of India.Government of India Press, NewDelhi, India.

Kitching, R.L., Orr, A.G., Thalib, L.,Mitchell, H., Hopkins, M.S., andGraham, A.W. 2000. Mothassemblages as indicators ofenvironmental quality in remnants ofupland Australian rainforest. Journal ofApplied Ecology 37, pp 284-297.

Summerville, K.S., Ritter, L.M., andCrist, T.O. 2003. Forest moth taxa asindicators of Lepidopteran richnessand habitat disturbance: a preliminaryassessment. Biological Conservation116, pp 9-18.

Website

http://www.eoearth.org/view/article/150643/

1.5

1.2

0.9

0.6

0.3

.0

rela

tive

abun

danc

e

Geometridae Lymantridae Drepanidae

Site 1 (Joshimath)Site 2 (Lata)

400

300

200

100

0

no. o

f mor

phos

peci

es

subtropicalbroadleafand pine

forest

Western Mixconiferousand Oak

forest

subalpineforest

alpine

Fig 1: The family Geometridae showed high abundance in both the study sites.

Fig. 2. The western mix coniferous forest showed highest species richness.