Digestion. Digestive System (Blank) Digestive System (Labeled)

Module 6 - AAPCcloud.aapc.com/.../AnatomyPathophysiology_Online_module6_UHC.pdf · Module 6...

Transcript of Module 6 - AAPCcloud.aapc.com/.../AnatomyPathophysiology_Online_module6_UHC.pdf · Module 6...

ii Anatomy and Pathophysiology for ICD-10 UnitedHealthcare © 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. 111213

DisclaimerThis course was current at the time it was published. This course was prepared as a tool to assist the participant in understanding how to prepare for ICD-10-CM. Although every reasonable effort has been made to assure the accu-racy of the information within these pages, the ultimate responsibility of the use of this information lies with the student. AAPC does not accept responsibility or liability with regard to errors, omissions, misuse, and misinterpre-tation. AAPC employees, agents, and staff make no representation, warranty, or guarantee that this compilation of information is error-free and will bear no responsibility, or liability for the results or consequences of the use of this course.

AAPC does not accept responsibility or liability for any adverse outcome from using this study program for any reason including undetected inaccuracy, opinion, and analysis that might prove erroneous or amended, or the coder’s misunderstanding or misapplication of topics. Application of the information in this text does not imply or guarantee claims payment. Inquiries of your local carrier(s)’ bulletins, policy announcements, etc., should be made to resolve local billing requirements. Payers’ interpretations may vary from those in this program. Finally, the law, applicable regulations, payers’ instructions, interpretations, enforcement, etc., may change at any time in any particular area.

This manual may not be copied, reproduced, dismantled, quoted, or presented without the expressed written approval of the AAPC and the sources contained within. No part of this publication covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (graphically, electronically, or mechanically, including photocopying, recording, or taping) without the expressed written permission from AAPC and the sources contained within.

ICD-10 ExpertsRhonda Buckholtz, CPC, CPMA, CPC-I, CGSC, CPEDC, CENTC, COBGC VP, ICD-10 Training and Education

Shelly Cronin, CPC, CPMA, CPC-I, CANPC, CGSC, CGIC, CPPM Director, ICD-10 Training

Betty Hovey, CPC, CPMA, CPC-I, CPC-H, CPB, CPCD Director, ICD-10 Development and Training

Jackie Stack, CPC, CPB, CPC-I, CEMC, CFPC, CIMC, CPEDC Director, ICD-10 Development and Training

Peggy Stilley, CPC, CPB, CPMA, CPC-I, COBGC Director, ICD-10 Development and Training

Illustration copyright © OptumInsight. All rights reserved.

©2013 AAPC2480 South 3850 West, Suite B, Salt Lake City, Utah 84120800-626-CODE (2633), Fax 801-236-2258, www.aapc.com

Revised 111213. All rights reserved.

CPC®, CPC-H®, CPC-P®, CPMA®, CPCO™, and CPPM® are trademarks of AAPC.

© 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. UnitedHealthcare www.aapc.com iii111213

Contents

Module 6 Digestive System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Terminology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1General Structure and Function of the Digestive System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2Specialized Epithelial Cells . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2Diseases, Disorders, Injuries, and Other Conditions of the Digestive System. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

© 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. UnitedHealthcare www.aapc.com 1111213

Module6

Digestive System

TerminologyAnastomosis—A surgical connection between two hollow, tubular structures.

Alimentary—Concerning food, nourishment, and the organs of digestion.

Bile—A bitter, yellow-green secretion of the liver.

Cecum—First portion of the large intestine situated in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen.

Colon—Part of the large intestine running from the cecum to the rectum assisting in food digestion and waste removal in the body.

Colostomy—A surgical procedure in which one end of the large intestine is brought out through the abdominal wall where stool is collected in a bag attached to the abdomen.

Duodenum—The first part of the small intestine extending from the pylorus (at the bottom of the stomach) to the jejunum.

Dyskinesia—Difficulty or distortion in performing voluntary movements.

Dysplasia—Abnormal growth or development of cells or organs.

Enterostomy—A surgical procedure in which one end of the small intestine is brought out through the abdom-inal wall where stool is collected in a bag attached to the abdomen.

Esophagostomy—Surgical creation of an artificial opening into the esophagus to allow for nutritional support.

Gastrostomy—Surgical creation of an artificial opening into the stomach to allow for nutritional support.

Hemorrhage—Bleeding or abnormal flow of blood.

Ileum—Lowest part of small intestine continuing from the jejunum, located just before the large intestine.

Jejunum—Part of the small intestine located between the duodenum and ileum.

Malabsorption—Impaired absorption of nutrient of food by the intestines.

Mastication—Chewing, tearing, or grinding food with teeth as it is mixed with saliva.

Perforation—A hole that develops through the entire wall of the stomach, small or large intestine, or gallbladder.

Pyloric sphincter—A muscular ring in the stomach that controls passage of food from the stomach into the duodenum.

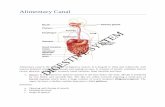

IntroductionThe digestive system is made up of the gastrointestinal tract (GI tract), also known as the alimentary canal. The mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intes-tine, large intestine, rectum, and anus all make up the digestive tract, which is basically a food-processing pipe about 30 ft. long. Associated digestive structures include three pairs of salivary glands, the pancreas, the liver, and the gallbladder, each with a very important role. The appendix—a short, blind-ended tube attached to the large intestine—has no known function. Food is moved through the digestive tract by muscular contractions called peristalsis until it is eliminated from the body.

The primary function of the digestive system is to break down the food we eat into smaller parts so the body can use it to build and nourish cells and provide energy. This process is carried out by:

• Ingesting food • The body propels the food through the GI tract

from mouth to anus

2 Anatomy and Pathophysiology for ICD-10 UnitedHealthcare © 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. 111213

Digestive System Module 6

• Mucus, water, enzymes, and other digestive substances are secreted to break the food down

• Food particles are mechanically and chemically digested into absorbable nutrients

• Digested particles are absorbed• Waste products are eliminated from the body

through defecation

Food enters the digestive system through the mouth and is cut, crushed, and ground by teeth. The muscular tongue moves the food around in the mouth. As food is swallowed it moves down the pharynx (throat), where salivary glands secrete saliva, which contains enzymes to start digestion. It continues to be propelled through the esophagus and into the stomach. The stomach is a J-shaped muscular bag that adds gastric acids while it churns, digests, and stores food. The food becomes liquefied to enter the small intestine where additional chemical secretions from the pancreas, liver, and gall-bladder are added to digest the food into absorbable nutrients. The walls of the small intestines absorb the nutrients while unused waste products move into the colon, or large intestine where fluid is removed. Waste then becomes solid and is defecated through the anus.

General Structure and Function of the Digestive System Remarkably diverse and specialized processes take place in different sections of the digestive tract, but there is a fundamental consistency in the architecture of the tubular digestive tract. From the mouth to the anus, the wall of the digestive tube is composed of four basic layers or tunics. The layers vary in thickness and tissue/cell type (connective, muscle, and epithelial). They have sublayers and contain other functional structures, such as glands, blood and lymph vessels, and nerve fibers. Beginning with the innermost layer, the four layers of the digestive tube are the:

• Mucosa• Submucosa• Muscularis • Serosa

Source: AAPC

The mucosa is the innermost layer of tissue lining the GI tract. It contains three sublayers: mucous epithelium, lamina propria, and muscularis mucosae. Certain cells in the mucosa secrete mucus, digestive enzymes, and hormones. Ducts from other glands pass through the mucosa to the lumen. In the mouth and anus, where thickness for protection against abrasion is needed, the epithelium is stratified squamous tissue. The stomach and intestines have a thin simple columnar epithelial layer for secretion and absorption.

The submucosa is a thick layer of loose connective tissue that surrounds the mucosa. This layer also contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves. Glands may be embedded in this layer.

Above the diaphragm, the outermost layer of the GI tract is a connective tissue called adventitia. Below the diaphragm, it is called serosa.

Specialized Epithelial CellsThe digestive system contains a number of highly specialized cell types, each of which has very specific functions. Epithelial cells line the inner surface of the stomach, and secrete about 2 liters of gastric juices per day. Gastric juice contains hydrochloric acid, pepsin-ogen, and mucus, which are important digestive ingre-dients. Secretions are controlled by nervous (smells,

© 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. UnitedHealthcare www.aapc.com 3111213

Module 6 Digestive System

thoughts, and caffeine) and endocrine signals. Most of the cells carrying out the functions of the GI system are specialized epithelial cells.

Liver

Esophagus

PharynxOral cavity

Duodenum

Transversecolon

Jejunum

AscendingcolonIleum

Appendix

Gallbladder

Cecum

Anal canal

RectumSigmoidcolon

Descendingcolon

Stomach

Digestive Tract

Site ofileocecal

valve

Copyright OptumInsight. All rights reserved

Organ Function in the Digestive System The digestive system has the unique function of turning food into energy needed for survival and removing unused products for waste disposal. They work together in a very complex way and consist of the mouth (oral cavity), the esophagus, the stomach, the small and large intestines, and the accessory organs of digestion: the liver, gallbladder, and exocrine pancreas.

The mouth is the beginning of the digestive tract; and, in fact, digestion starts here when taking the first bite of food. Chewing breaks the food into pieces that are more

easily digested, while saliva mixes with food to begin the process of breaking it down into a form your body can absorb and use. The tongue, salivary glands, and the teeth are critical to the digestion process in the oral cavity. Taste buds are clusters of cells on the tongue that respond to food by initiating secretion of saliva (up to one liter each day) and gastric acid.

The esophagus, which is located in your throat near the trachea, receives food from your mouth when it is swal-lowed. Each end the esophagus is opened and closed by a sphincter. The upper esophageal sphincter prevents air from entering the esophagus during respiration. Normally, the lower esophageal sphincter closes after food enters the stomach; however, if it fails to close or remains closed, gastric juices may flow back into the esophagus, causing gastroesophageal reflux. Rhythmic contractions occur, called peristalsis, to propel liquids and solids through the esophagus to the stomach.

The stomach is a hollow organ, or “container,” that holds food while it is being mixed with enzymes that continue the process of breaking down food into a usable form, called chyme. It has three major parts: the fundus, which is the upper rounded portion of the stomach, the body, which is the central part of the stomach, and the pylorus, which is the lower tubular part of the stomach. Cells in the lining of the stomach secrete strong acid and powerful enzymes that are responsible for the breakdown process. When the contents of the stomach are sufficiently processed, they are released into the small intestine. Gastric juices are composed of digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid. A thick mucus layer coats the mucosa and helps keep the acidic digestive juice from dissolving the tissue of the stomach itself.

The small intestine is made up of three segments—the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum—the small intestine is a 22-foot long muscular tube that breaks down food using enzymes released by the pancreas and bile from the liver. Peristalsis also is at work in this organ, moving food through and mixing it with digestive secretions from the pancreas and liver. The duodenum is largely responsible for the continuous breaking-down process, with the jejunum and ileum mainly responsible for absorption of nutrients into the bloodstream.

Contents of the small intestine start out semi-solid, and end in a liquid form after passing through the organ.

4 Anatomy and Pathophysiology for ICD-10 UnitedHealthcare © 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. 111213

Digestive System Module 6

Water, bile, enzymes, and mucous contribute to the change in consistency. Once the nutrients have been absorbed and the leftover-food residue liquid has passed through the small intestine, it then moves on to the large intestine, or colon.

The pancreas secretes digestive enzymes into the duodenum, the first segment of the small intestine. These enzymes break down protein, fats, and carbo-hydrates. The pancreas also makes insulin, secreting it directly into the bloodstream. Insulin is the chief hormone for metabolizing sugar.

The liver has multiple functions, but its main function within the digestive system is to process the nutrients absorbed from the small intestine. Bile from the liver is stored in the gallbladder in between meals. At mealtime, it is squeezed out of the gallbladder, through the bile ducts, and into the intestine to mix with the fat in food. The bile acids dissolve fat into the watery contents of the intestine, which are digested by enzymes from the pancreas, and the lining of the intestine. In addition, the liver is the body’s chemical “factory.” It takes the raw materials absorbed by the intestine and makes all the various chemicals the body needs to function. The liver also detoxifies potentially harmful chemicals. It breaks down and secretes many drugs.

The colon (or large intestine) is a 6-foot long muscular tube that connects the small intestine to the rectum. The large intestine is made up of the cecum, the ascending (right) colon, the transverse (across) colon, the descending (left) colon, and the sigmoid colon, which connects to the rectum. The appendix is a small tube attached to the cecum. The large intestine is a highly specialized organ that is responsible for processing waste so that emptying the bowels is easy and convenient.

Ascendingcolon

Descendingcolon

Sigmoid

Splenic

Sigmoid colon

Appendix

Hepatic

Rectum

15%

10 %

5%

20 %50%

Anatomical distributionof large bowel cancers

Transverse colon

Copyright OptumInsight. All rights reserved

Stool, or waste left over from the digestive process, is passed through the colon by means of peristalsis, first in a liquid state and ultimately in a solid form. As stool passes through the colon, water is removed. Stool is stored in the sigmoid (S-shaped) colon until a “mass movement” empties it into the rectum once or twice a day. It normally takes about 36 hours for stool to get through the colon. The stool itself is mostly food debris and bacteria. These bacteria perform several useful func-tions, such as synthesizing various vitamins, processing waste products and food particles, and protecting against harmful bacteria. When the descending colon becomes full of stool, or feces, it empties its contents into the rectum to begin the process of elimination.

The rectum is an 8-inch chamber that connects the colon to the anus. It is the rectum’s job to receive stool from the colon, to let the person know that there is stool to be evacuated, and to hold the stool until evacuation happens. When anything (gas or stool) comes into the rectum, sensors send a message to the brain. The brain then decides if the rectal contents can be released or not. If they can, the sphincters relax and the rectum contracts, disposing its contents. If the contents cannot be disposed, the sphincter contracts and the rectum accommodates so that the sensation temporarily goes away.

The anus is the final part of the digestive tract. It is a two-inch long canal consisting of the pelvic floor muscles and the two anal sphincters (internal and external). The lining of the upper anus is specialized to detect rectal contents. It lets you know whether the contents are liquid, gas, or solid. Sphincter muscles that

© 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. UnitedHealthcare www.aapc.com 5111213

Module 6 Digestive System

are important in allowing control of stool surround the anus. The pelvic floor muscle creates an angle between the rectum and the anus that stops stool from coming out when it is not supposed to. The internal sphincter is always tight, except when stool enters the rectum. It keeps us continent when we are asleep or otherwise unaware of the presence of stool. When we get an urge to go to the bathroom, we rely on our external sphincter to hold the stool until reaching a toilet, where it then relaxes to release the contents.

Diseases, Disorders, Injuries, and Other Conditions of the Digestive SystemEsophageal DisordersA very common disorder that can affect the esophagus is Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), which is caused by weakness of the lower esophageal sphincter. Stomach acid is normally removed from the esophagus through the process of peristalsis, squeezing movements to push acid into the stomach. The sphincter may not close tightly enough or may relax too much during the course of the day or at night causing the backflow of acid and bile found in the stomach to aide in the digestion process. Barrett’s esophagus is a condition in which the lining of the esophagus is damaged, most commonly found in patients with GERD due to chronic inflamma-tion of the esophagus. A diagnosis of Barrett’s esoph-agus may be concerning because it increases the risk of a patient developing esophageal cancer.

The ICD-10-CM code range for disorders of the esoph-agus is K20.0–K23

Eosinophilic esophagitis K20.0Other esophagitis K20.8Esophagitis, unspecified K20.9Achalasia of cardia K22.0Ulcer of esophagus without bleeding K22.10Ulcer of esophagus with bleeding K22.11Esophageal obstruction K22.2Perforation of esophagus K22.3Dyskinesia of esophagus K22.4

Diverticulum of esophagus, acquired K22.5gastro-esophageal laceration-hemorrhage syndrome

K22.6

Barrett’s esophagus without dyspla-sia K22.70Barrett’s esophagus with low grade dysplasia

K22.710

Barrett’s esophagus with high grade dysplasia

K22.711

Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia, unspecified

K22.719

Other specified diseases of the eso-phagus K22.8Diseases of esophagus, unspecified K22.9Disorders of esophagus in diseases classi-fied elsewhere

K23

Stomach and Duodenal UlcersUlcers are open sores or lesions. They are found in the skin or mucous membranes of areas of the body. A stomach ulcer is called a gastric ulcer and an ulcer in the duodenum is called a duodenal ulcer. Lifestyle, stress and diet used to be thought to cause ulcers. These factors may have a role in ulcer formation; however, they are not the main cause of them. Scientists now know that ulcers are caused by hydrochloric acid and pepsin that are contained in our stomach and duodenal parts of our digestive system and that these acids contribute to ulcer formation.

The ICD-10-CM code range for stomach and duodenal ulcers is K25.0–K28.9.

6 Anatomy and Pathophysiology for ICD-10 UnitedHealthcare © 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. 111213

Digestive System Module 6

Source: AAPC

The following information is required to code for these types of ulcers:

• Acute or chronic condition• Hemorrhage• Perforation• Hemorrhage with perforation• Without hemorrhage or perforation

Acute gastric ulcer with hemorrhage K25.0

Acute gastric ulcer with perforation K25.1

Acute gastric ulcer with both hemorrhage and perforation K25.2

Acute gastric ulcer without hemorrhage or perforation K25.3

Chronic or unspecified gastric ulcer with hemorrhage K25.4

Chronic or unspecified gastric ulcer with perforation K25.5

Chronic or unspecified gastric ulcer with both hemorrhage and perforation K25.6

Chronic or unspecified gastric ulcer without hemorrhage or perforation K25.7

Gastric ulcer, unspecified as acute or chronic, without hemorrhage or perforation

K25.9

Currently there are no ICD-10-CM guidelines specifically related to this condition.

Knottedintestine(volvulus)

Diverticulum

Copyright OptumInsight. All rights reserved

Diverticulitis and Diverticulosis Pressure within the colon causes bulging pockets of tissue (sacs) that push out from the colonic walls as a person ages. A small bulging sac pushing outward from the colon wall is called a diverticulum. More than one bulging sac is referred to in the plural as diverticula. Diverticula can occur throughout the colon but are most common near the end of the left colon referred to as the sigmoid colon. The condition of having these diverticula in the colon is called diverticulosis, which is a very common condition. It is found in more than half of Americans over age 60. Only a small percentage of these people will develop the complication of

© 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. UnitedHealthcare www.aapc.com 7111213

Module 6 Digestive System

diverticulitis. Inflammation or a small tear in a diver-ticulum causes diverticulitis. If the tear is large, stool in the colon can spill into the abdominal cavity, causing an infection or abscess in the abdomen. Symptoms include abdominal pain, chills, fever, nausea, vomiting, or weight loss. Eating foods high in fiber can reduce the risk for this condition.

The ICD-10-CM code range for Diverticulitis and Diver-ticulosis is K57.00–K57.93.

The following information is required to code for this these conditions:

• Site of inflammation or disease• Perforation or abscess• If bleeding is present

Diverticulitis of small intestine with perfo-ration and abscess K57.0

Diverticulitis of small intestine with perfo-ration and abscess without bleeding K57.00

Diverticulitis of small intestine with perfo-ration and abscess with bleeding K57.01

Diverticular disease of small intestine without perforation or abscess K57.1

Diverticulosis of small intestine without perforation or abscess without bleeding K57.10

Diverticulosis of small intestine without perforation or abscess with bleeding K57.11

Diverticulitis of small intestine without perforation or abscess without bleeding K57.12

Diverticulitis of small intestine without perforation or abscess with bleeding K57.13

Diverticular disease of large intestine without perforation or abscess K57.3

Diverticulosis of large intestine without perforation or abscess without bleeding K57.30

Diverticulosis of large intestine without perforation or abscess with bleeding K57.31

Diverticulitis of large intestine without perforation or abscess without bleeding K57.32

Diverticulitis of large intestine without perforation or abscess without bleeding K57.33

In the table, the information that is necessary in the documentation is shown. Indication of where the disease or inflammation is located as well as if perforation or abscess, and if bleeding is present is vital in coding diverticulitis or diverticulosis.

Directinguinalhernia

(betweendeep inferior

epigastricvessels and

rectus fascia)

Incarceratedhernia

Copyright OptumInsight. All rights reserved

HerniasA hernia is the protrusion of an organ or the fascia of an organ through the wall of the cavity that normally contains it. A hiatal hernia occurs when the stomach protrudes into the mediastinum through the esophageal opening in the diaphragm.

By far the most common hernias develop in the abdomen, when a weakness in the abdominal wall evolves into a localized hole, or “defect”, through which fatty tissue, or abdominal organs covered with perito-neum, may protrude. Hernias may or may not present either with pain at the site, a visible or palpable lump, or in some cases by more vague symptoms resulting from

8 Anatomy and Pathophysiology for ICD-10 UnitedHealthcare © 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. 111213

Digestive System Module 6

pressure on an organ which has become “stuck” in the hernia, sometimes leading to organ dysfunction. Fatty tissue usually enters a hernia first, but it may be followed by or accompanied by an organ. Most of the time, hernias develop when pressure in the compartment of the residing organ is increased, and the boundary is weak or weakened.

Many conditions chronically increase intra-abdominal pressure, (pregnancy, ascites, COPD, dyschezia, benign prostatic hypertrophy) and explain why abdominal hernias are very common.

The ICD-10-CM code range for hernias is K40.00–K46.9.

The following information is required to code for these conditions:

• Site of hernia• Laterality, when appropriate• If gangrene or obstruction is present • If condition is recurrent

Bilateral inguinal hernia, with obstruction, without gangrene, not specified as recurrent K40.00

Bilateral inguinal hernia, with obstruction, without gangrene, recurrent K40.01

Unilateral inguinal hernia, with obstruction, without gangrene, not specified as recurrent K40.30

Unilateral inguinal hernia, with obstruction, without gangrene, recurrent K40.31

Bilateral inguinal hernia with gangrene, not specified as recurrent K40.10

Bilateral inguinal hernia with gangrene, recurrent K40.11

Unilateral inguinal hernia, with gangrene, not specified as recurrent K40.40

Unilateral inguinal hernia, with gangrene, recurrent K40.41

Bilateral inguinal hernia, without obstruction or gangrene, not specified as recurrent

K40.20

Bilateral inguinal hernia, without obstruction or gangrene, recurrent K40.21

Unilateral inguinal hernia, without obstruction or gangrene, not specified as recurrent

K40.90

Unilateral inguinal hernia, without obstruction or gangrene, recurrent K40.91

In the table above, the laterality is shown (as appropriate depending on the hernia). The fourth digits indicate the presence of an obstruction or gangrene, while the fifth digits indicate if the condition is specified as recurrent or not.

The guidelines that precede this section in the tabular area indicate that a hernia with both gangrene and obstruction is classified to hernia with gangrene.

Gallstone in fundus Hartmann’s

pouch(infundibulum)

Cysticduct

Cystic artery

Right hepatic artery Right and left bile ducts

Triangle ofCalot

Commonhepaticartery

Portalvein

Commonbile ductemptiesintoDuodenum

Copyright OptumInsight. All rights reserved

© 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. UnitedHealthcare www.aapc.com 9111213

Module 6 Digestive System

CholelithiasisCholelithiasis is the presence of one or more calculi (gallstone) in the gallbladder. Gallstones are hard, pebble-like deposits that form inside the gallbladder. They may be as small as a grain of sand or as large as a golf ball. Failure of the gallbladder to empty bile prop-erly (likely to happen during pregnancy), and medical conditions that causes the liver to make too much bili-rubin can commonly cause one to develop gallstones. The most common types of gallstones are the ones made out of cholesterol, which has nothing to do with the cholesterol levels in the blood.

Choledocholithiasis occurs if a large stone blocks either the cystic duct or the common bile duct causing cramping pain in the middle to right upper abdomen. The pain is relieved if the stone passes into the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum). Other possible symptoms may include fever, yellowing of skin and whites of eyes (jaundice), abdominal fullness, clay-colored stools, and nausea and vomiting.

Cholangitis is an infection of the common bile duct, the tube that carries bile from the liver to the gallbladder and intestines. It is usually caused by a bacterial infec-tion, which can occur when from blockage of the duct, such as a gallstone or tumor.

The ICD-10-CM code range for disorders of gallbladder, biliary tract and pancreas is K80.00–K87.

The following information is required to code for these conditions:

• Site • Acute or chronic• With or without obstruction

Calculus of gallbladder with acute cholecystitis without obstruction K80.00

Calculus of gallbladder with acute cholecystitis with obstruction K80.01

Calculus of gallbladder with chronic cholecystitis without obstruction K80.10

Calculus of gallbladder with chronic cholecystitis with obstruction K80.11

Calculus of gallbladder with acute and chronic cholecystitis without obstruction K80.12

Calculus of gallbladder with acute and chronic cholecystitis with obstruction K80.13

Calculus of gallbladder with other cholecystitis without obstruction K80.18

Calculus of gallbladder with other cholecystitis with obstruction K80.19

Calculus of the bile duct with cholangitis, unspecified, without obstruction K80.30

Calculus of the bile duct with cholangitis, unspecified, with obstruction K80.31

Calculus of the bile duct with acute cholangitis, without obstruction K80.32

Calculus of the bile duct with acute cholangitis with obstruction K80.33

Calculus of the bile duct with chronic cholangitis without obstruction K80.34

Calculus of the bile duct with chronic cholangitis with obstruction K80.35

Calculus of the bile duct with acute and chronic cholangitis without obstruction K80.36

Calculus of the bile duct with acute and chronic cholangitis with obstruction K80.37

The table above demonstrates the importance of specifying if the condition is acute or chronic, and where the stones are located, as well as if there is an obstruction present.

10 Anatomy and Pathophysiology for ICD-10 UnitedHealthcare © 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. 111213

Digestive System Module 6

Intraoperative and postprocedural complicationsComplications of procedures performed on the diges-tive system codes are found in the digestive chapter. The codes in ICD-10-CM for complications of surgery on the digestive system are found in categories K91–K94.39. They are classified as “intraoperative” and “postpro-cedural”, and additional information will need to be obtained if it is not documented in the note. Some of these complications include obstruction, hemorrhage, hematoma, and infection. In patients who have had gastric bypass surgery some of the complications may also include vomiting, dumping syndrome, and post-surgical malabsorption. Dumping syndrome occurs when the patient eats foods rich in sugar content and the body floods the intestines in an attempt to dilute the sugar. The patient may experience a rapid and forceful heart rate and anxiety as well as nausea, which may also be followed by diarrhea. Due to the fact that gastric bypass surgery reduces the amount of food that the stomach can store, it is very important for these patients to ensure that the food they ingest provides a good balance of nutrition. Not only does their intake amount decline, but also the rate at which their bodies absorb the food. The number of acid producing cells in the lining of the stomach increase after bypass surgery so the physician may recommend use of acid reducing medications, which may then cause a condition known as achlorhydria (not enough acid in the stomach). With such low levels of acidity in the stomach, patients are at risk of developing overgrowth of bacteria in the stomach causing nausea and vomiting. Extended symptoms of nausea and vomiting will lead to malnutrition so the physician must closely monitor the level of acidity in the stomach and the patient must work closely with a dieti-tian to ensure a well-balanced intake of foods.

The ICD-10-CM code range for Intraoperative and postprocedural complications is K91.0–K94.39.

The following information is required to code for these conditions:

• Intraoperative or postprocedural complication• Type of complication • Type of procedure performed

Vomiting following gastrointestinal surgery K91.0Postgastric surgery syndromes K91.1Postsurgical malabsorption, not elsewhere classified

K91.2

Postprocedural intestinal obstruction K91.3Postcholecystectomy syndrome K91.5Intraoperative hemorrhage and hematoma of a digestive system organ or structure complicating a digestive system procedure

K91.61

Intraoperative hemorrhage and hematoma of a digestive system organ or structure complicating other procedure

K91.62

Accidental puncture and laceration of a digestive system organ or structure during a digestive system procedure

K91.71

Accidental puncture and laceration of a digestive system organ or structure during a digestive system procedure

K91.72

Other intraoperative complications of digestive system

K91.81

Postprocedural hepatic failure K91.82Postprocedureal hepatorenal syndrome K91.83Postprocedural hemorrhage and hematoma of a digestive system organ or structure following a digestive system procedure

K91.840

Postprocedural hemorrhage and hematoma of a digestive system organ or structure following other procedure

K91.841

Pouchitis K91.850Other complications of intestinal pouch K91.858Other postprocedural complications and disorders of digestive system

K91.89

Additionally, there are specific ICD-10-CM codes for reporting complications of artificial openings of the digestive system. These codes require the following information:

• Type of surgery that caused the artificial opening • Type of complication

Colostomy complication, unspecified K94.00Colostomy hemorrhage K94.01

© 2013 AAPC. All rights reserved. UnitedHealthcare www.aapc.com 11111213

Module 6 Digestive System

Colostomy infection K94.02Colostomy malfunction K94.03Other complications of colostomy K94.09Enterostomy complication, unspecified K94.10Enterostomy hemorrhage K94.11Enterostomy infection K94.12Enterostomy malfunction K94.13Other complications of enterostomy K94.19Gastrostomy complication, unspecified K94.20Gastrostomy hemorrhage K94.21Gastrostomy infection K94.22Gastrostomy malfunction K94.23Other complications of gastrostomy K94.29Esophagostomy complication, unspecified K94.30Esophagostomy hemorrhage K94.31Esophagostomy infection K94.32Esophagostomy malfunction K94.33Other complications of esophagostomy K94.39

When coding for an infection, ICD-10-CM instructs the user to:

Use additional code to specify type of infection, such as:

Cellulitis of abdominal wall (L03.32)Sepsis (A40.-, A41.-)

SourcesComprehensive Medical Terminology (Fourth Edition) by Betty Davis Jones.

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary, 28th edition

Bates’ Pocket Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking, Third Edition (Lynn S. Bickley-Lippincott)