Michael Goebel

-

Upload

camila-alvarez -

Category

Documents

-

view

53 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Michael Goebel

Bulletin of Latin American Research, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 356–377, 2007

© 2007 The AuthorJournal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies. Published by Blackwell Publishing,

356 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

A Movement from Right to Left in Argentine Nationalism? The Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista and Tacuara as Stages of Militancy

MICHAEL GOEBEL University College London, UK

This article contributes to debates about fascist infl uences among Argenti-na ’ s guerrilla groups of the 1970s. From the overall perspective of developments in Argentine nationalism, it traces back the history of the far-right Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista and Tacuara and as-sesses their signifi cance as the nuclei from which later guerrillas came. Based on police reports and periodical publications from the period in question (c.1937 – c.1973), it makes some generalisations about the collective biographies of militants. While not contradicting the widely held view that originally fascist groupings played a role in the emer-gence of Argentine guerrillas, the article introduces some nuances into this argument. Particular emphasis is given to the role of Peronism and the Cuban Revolution as facilitators of changes in Argentine nationalism.

Keywords : Argentina , nationalism , Peronism , guerrillas , fascism .

Introduction 1

In contrast to many Latin American countries where the Left successfully appropri-ated the banner of the nation, Argentine nationalism has usually been interpreted as belonging to the political Right. As with so many other issues, in this respect, too, Argentina appears more European than Latin American. Since US imperialism was less tangible in Argentina than elsewhere in the region and because Argentine intellectuals closely observed Old World developments, so the argument goes, the dominant form

1 I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and Mora González Canosa for her help in accessing the material of the ACPM. Names in these police reports are deleted, which reduces their value for research, but except for long lists, the names can usually be inferred from secondary sources, especially periodicals of the time.

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 357

Argentine Nationalism

of nationalism was infl uenced by southern European and French variants of authori-tarianism that were in vogue in the interwar period, rather than projecting itself as a popular struggle for national liberation from the overwhelming hegemony of foreign powers. If the Cambridge History of Latin America is a seismograph of standard scholarship on the region, David Rock ’ s view (1991: 35) that in Argentina even anti-imperialism, the classical touchstone between nationalism and the Left, developed around a set of conspiracy theories that resembled the tactics and beliefs of the Right rather than the Left, can be seen as paradigmatic. As Tulio Halperin Donghi (1999: 167) has noted, ‘ the Right [ … ] won the anti-imperialist high ground by default ’ . Sandra McGee Deutsch (1999: 315) has argued that the Argentine extreme Right was more successful than its Brazilian and Chilean counterparts in shaping its country ’ s political culture.

However, there was also a more left-leaning form of nationalism in Argentina. For the interwar period, this has usually been associated with FORJA, a populist group that broke away from the Radical Party in 1935 ( Buchrucker, 1987: 258 – 276 ). It is debatable how important or representative this group was for Argentine nationalism as a whole in the 1930s, but if FORJA is not enough to persuade sceptics of the existence of left-wing nationalism in Argentina, even a superfi cial look at the climate of ideas in the 1960s should instantly win them over. In contrast to the interwar period, after the Cuban Revolution, Argentina ’ s ‘ New Left ’ became hegemonic in public debate ( Hilb and Lutzky, 1984 ). The ideas of this ‘ New Left ’ may have been so eclectic as to make it necessary to speak of it in the plural, but nationalism, anti-imperialism and Third World solidarity were elements common to all its countless ramifi cations. The Argentine guerrilla groups of the early 1970s, both the Peronist ones such as the Montoneros and the Trotskyist Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP), embraced tercermundismo , nationalism and Marxism, as did virtually all forms of left-wing nationalism in Latin America. Most of the by then elderly authoritarian nationalists of the interwar period, and in particular the traditionalists, strongly disapproved of the young self-declared revolutionaries ( Ibarguren, 1971: 48 – 49 ). Conversely, Marxist nationalist intellectuals like Juan José Hernández Arregui (1960) and Rodolfo Puiggrós (1968: 47 – 66) , whose writings formed the reading matter of the nascent left-wing nationalist groups, devoted a great deal of effort to differentiating themselves from the more elitist and often hispanista , Catholic and anti-Semitic nationalism of the 1930s. In order to distinguish between such different forms of na-tionalism, English-language studies (e.g. McGee Deutsch and Dolkart, 1993; McGee Deutsch, 1999 ) have employed the Spanish term nacionalismo to denote the authori-tarian right-wing strand that gained momentum between 1930 and 1943 as one particular, but not the only, kind of Argentine nationalism.

However, it has also been argued that Argentina ’ s left-wing nationalism of the 1960s and 1970s was underpinned by ideas taken from nacionalismo . Alan Angell ’ s remark in the Cambridge History of Latin America that the Montoneros drew on ‘ right-wing nationalist ideas that had inspired the neo-fascist movements of the previous decades ’ (1994: 204) can again be taken as representative. Similarly, Rock has maintained that ‘ the Nationalists [i.e. right-wing nacionalistas ] had a major infl uence on the Argentine revolutionary Left [ … which] inherited the cult of authoritarian

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 358 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

leadership from the Nationalists and copied their attempt to create a radical counter-culture ’ (1993: xiv – xv). Yet apart from the oft-noted fact that the Montoneros drew on earlier right-wing motifs, the actual transition from the predominant forms of nationalism in the 1930s to the left-leaning guerrillas has rarely been studied. It has remained unclear how signifi cant such links were for the emergence of the nationalist urban guerrillas of the 1960s and 1970s, numerically or ideologically. The apparent ease with which the metamorphosis of Argentine nationalism from Right to Left unfolded has thus remained rather ‘ surprising ’ , as Rock (1993 : xiv) has observed.

This article seeks to contribute to our understanding of these changes in Argentine nationalism by exploring the trajectories of the members of the only two nacionalista groups that were of signifi cance as nuclei from which later guerrillas sprang: the Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista and Tacuara. The reconstruction of their history has been made easier through recent scholarly studies of left-wing guerrillas since 1959 ( Rot, 2000; Salas, 2003; Pozzi, 2004; Lanusse, 2005 ) and journalistic books or accounts by former militants about the relationships between nacionalista groups and the guerrillas ( Gurucharri, 2001; Bardini, 2002; Pérez, 2002; Gutman, 2003; Beraza, 2005 ). Taken together, these works have solidifi ed the base for assessing the weight of nacionalismo in Argentina ’ s left-wing nationalism after the Cuban Revolution. These sources are complemented by reports of the police intelligence unit of Buenos Aires province on nacionalista groups in the 1960s and 1970s (ACPM) and by periodical publications of the time. The article fi rst delineates the development of the Alianza since the late 1930s, followed by a survey of the history of Tacuara. The third section traces back the input of the Alianza and Tacuara into the various Argentine guerrillas. I will stress a number of commonalities in the development of these groups, such as the impact of international events and the centrality of populism. To describe the way in which populist discourse acted as a medium of communication between right- and left-wing nationalism, I will draw on the work of Ernesto Laclau (1977 : 143 – 198: 2005) and Silvia Sigal and Eliseo Verón (2003).

The Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista

The history of the Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista (ALN) ranged from far-Right radicalism to an identifi cation with populism. In this, the group refl ected broader developments in nacionalismo . From the mid-1930s onwards, after the disintegration of José Félix Uriburu ’ s military regime, some nacionalistas wanted to extend popular participation and sought to leave behind elitism. Instead of attacking communism, they began to single out British imperialism, the cosmopolitan intelligentsia and the liberal oligarchy as the main targets of their vitriolic broadsides (e.g. Irazusta and Irazusta, 1982 ), thus establishing the ground for a limited degree of overlap with FORJA ’ s ideas. This change was typically expressed in historical revisionism, a current of writing that glorifi ed nineteenth-century caudillos , especially Juan Manuel de Rosas, as the true embodiment of Argentina ’ s grandeur. Rosas, according to revisionists, had heroically fought against conspiracies between foreign intruders and effeminate liberals such as Domingo Faustino Sarmiento ( Quattrocchi-Woisson, 1992 ).

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 359

Argentine Nationalism

The Alianza went especially far in its turn to populism. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, it developed into a fascist organisation, which was then overshadowed and absorbed by Peronism. The organisation ’ s predecessor, the Legión Cívica Argentina (LCA), had been founded in 1930 by conservatives linked to traditional organisations of the establishment, but it had soon turned into a paramilitary squad to attack political opponents. 2 Scholarly opinions diverge as to whether the Legión itself already merited being described as fascist ( McGee Deutsch, 1999 : 245; Spektorowski, 2003: 88 – 89 ) or not ( Navarro Gerassi, 1968 : 91 – 105; Klein, 2002 ). In any event, after 1935, when the Legión adopted a more revolutionary rhetoric and plebeian outlook, its importance and membership began to dwindle and it was soon overshadowed by its subsidiary, which became the largest nacionalista group, advancing further on the road towards a fascist model.

Under Juan Queraltó ’ s leadership, the newly founded youth branch of the Legión, the Unión Nacionalista de Estudiantes Secundarios (UNES, founded in 1935), developed into the Alianza de la Juventud Nacionalista (AJN) (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 18744: 1; Queraltó, 1985 ), which in 1943 eventually changed its name to Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista (ALN). The Alianza (both AJN and its successor ALN) had an inclination to street agitation ( Ibarguren, 1971 : 43 – 44; Oliver, 1973: 40 ), with a fascist slant. Among its main aims was the mobilisation of the lower middle and working classes, staging large demonstrations on May Day from 1938 onwards ( La Nación , 2 May 1938 and 2 May 1943). According to Queraltó, these reached a peak of 20,000 marchers in 1943 ( Queraltó, 1985: 68 ). Even though it was in practice undermined by infi ghting, the Alianza ’ s structure was theoretically based on strict hierarchical principles, stressing subordination to an undisputed leader, group discipline and certain symbols, such as the Roman salute and insignia with an aesthetic derived from Nazism ( Klein, 2001: 104 – 105 ). By the early 1940s, the Alianza had become the largest nacionalista faction, counting between 10,000 and 50,000 mem-bers, many of whom came from urban immigrant families. 3 It was an organisation dominated by young men. Queraltó, the son of a lower-middle-class Spanish trades-man, was 23 by the time of the AJN ’ s foundation in 1937 and Alberto Bernaudo, the second in rank, was not yet twenty ( Klein, 2001: 104 ). Accounts by former members suggest that in the mid-1940s most of the ALN ’ s members were secondary

2 The fi gures given as to the Legión ’ s membership at this time vary widely. Dolkart (1993: 68) speaks of up to 50,000 members in the capital alone, without giving a source for this fi gure, which presumably is derived from the Legión ’ s leader ’ s own estimate, which Klein (2002: 12 – 13) mentions, but dismisses as unrealistic. Buchrucker (1987: 234) gives the most conservative estimate of 6,000 to 10,000, Spektorowski (2003: 100) estimates 10,000 to 30,000. The problem partly stems from the sudden rise in membership under Uriburu and its decline from 1932 onwards.

3 The problem with fi gures applies again. Navarro Gerassi (1968: 148) estimates 11,000 members shortly before the renaming as ALN, McGee Deutsch (1999: 233) between 30,000 and 50,000 ‘ adherents ’ . Another contentious issue is the number of women among the AJN, which according to Navarro Gerassi (1968: 148) was 3,000, a fi gure dismissed as far too high by Klein (2001: 115) .

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 360 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

school students below the age of twenty (ACPM, Mesa C, Legajo no. 75 [1960]; de Imaz, 1977: 26 – 37; Walsh, 1996: 14 ).

Ideologically, while Catholicism remained a main feature at this point, the Alianza of the early 1940s stressed social justice and national sovereignty in its slogans. In addition to the anti-liberalism and anti-communism that was customary among nacionalistas , the ALN-ideologue Bonifacio Lastra, on a rally in 1941, underlined that the group ’ s main task was to win over workers who would be as oppressed by communism as they were by capitalism (1944: 37). Furthermore, ‘ the movement upholds the need to establish a corporative system based on cooperation ’ , which required ‘ spiritual change ’ (1944: 36). The Alianza ’ s statutes championed the nation-alisation of key industries, the break-up of large latifundios , the unionisation of labour and the revolutionary abolition of what they depicted as the moribund bour-geois order ( Navarro Gerassi, 1968: 149 ). In addition, the Alianza was strongly anti- Semitic. For example, Ramón Doll, another Alianza-ideologue, identifi ed ‘ the ulcers of the country ’ as ‘ Judaism, materialism and intellectualism ’ (1939: 63). In practice, too, the Alianza of the mid-1940s was characterised by violent anti-Semitic and anti-communist street fi ghts ( La Nación , 23 December 1945; Navarro Gerassi, 1968 : 203; Rein, 2003: 33 ).

From the time of the right-wing military coup of 1943, which was supported by the newly established ALN, the organisation drew closer to the rising Perón ( Queraltó, 1985: 68 ). In the hours after the pro-Perón demonstration of 17 October 1945, a seventeen-year-old member of the Alianza, Darwin Passaponti, was shot dead and was henceforth revered as both a Peronist and a nacionalista martyr (e.g. Voz Peronista , 28 November 1958; Azul y Blanco , 20 October 1959). Although the Alianza presented its own candidates in the general elections of February 1946 and campaigned against the ratifi cation of the Act of Chapultepec ( Alianza , extra bulletin, August 1946; Oliver, 1973: 45 ), it was soon subordinated to and eclipsed by Peronism. The ALN ’ s electoral result of 28,320 votes in 1946 ( Canton, 1968: 130 ) showed its limited raison d ’ être under Peronism. With this, the organisation declined. Non-Peronist nacionalista intellectuals like Leonardo Castellani, Juan Pablo Oliver and José María Rosa withdrew from the ALN ( Oliver, 1973: 47 – 48 ) and it seems that many of the youths who had entered its ranks in 1945 did so too (de Imaz, 1977: 36). 4

Through an internal coup in 1953, the Alianza was effectively transformed into a Peronist squad that specialised in racketeering and the intimidation of the regime ’ s opponents. The anti-Semitic Queraltó was forcefully removed from the leadership and, apparently with police backing, replaced by the 31-year-old Guillermo Patricio Kelly, a maverick personality who dominated the increasingly dispersed group until the 1970s. In his inaugural declaration, Kelly vowed ‘ the iron determination of Argentine nacionalismo to support the leader of the Revolution, [ … ] Perón ’ ( La Nación , 19 April 1953; De Dios, 1984 : 21; Queraltó, 1985 : 70; Seoane, 2005 ). Abandoning the ALN ’ s

4 In 1948, the Unión Cívica Nacionalista broke away to maintain fascist purity against Peronist deviations ( Alianza , fi rst fortnight, October 1961). This group was later organically linked to Tacuara (see below, footnote 5).

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 361

Argentine Nationalism

anti-Semitism and even establishing good relations with the Israeli ambassador ( Rein, 2003: 68 ), the Alianza was among the last groups to resist the overthrow of Perón (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 4609 [1958]; Gutman, 2003: 43 ).

Very little is known about the ALN from 1955 onwards, which is largely due to the fact of its decline. After 1955, there were in fact several groups that claimed the name of the ALN, without there always being an organic connection between them. Since the Alianza had been turned into a tool of the Peronist government, it was strongly affected by the anti-Peronist repression. In November 1955, its 33 most notorious members, including Kelly, were imprisoned, while 21 remained free, of whom many became involved with the so-called Peronist resistance, whose main leader was John William Cooke ( Cooke and Perón, 1973 : 72; ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 4609 [1958]). It is impossible to establish membership fi gures for the period from 1955 to 1973 with certainty, but the police of the province of Buenos Aires clearly deemed the ALN a minor threat: its survey of the group consisted mostly of a collec tion of an irregularly published periodical, Alianza . The editors of this publication had at this point become largely independent from Kelly (ACPM, Mesa X, Legajo no. 199 [1961]), who spent much of the time from 1955 to 1963 in prison, with an interrup tion in 1957 that he used to visit Perón in Caracas (Cooke/Perón: 207; Compañero , 27 August 1963).

Whilst some ALN-elements for a while continued to propagate a blending of Peronism and nacionalismo , accompanied by slogans such as ‘ Dios, Patria y Hogar ’ [ ‘ God, Fatherland and Home ’ ] ( Alianza , fi rst fortnight, October 1961), there is evidence that other former members, especially outside the capital, joined Tacuara (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 14199: 413 [1972]; Padrón, 2006: 6 ).

After Kelly benefi ted from a general amnesty for political prisoners and was released in 1963, he sought to regain control and revive the group. Due to his contacts with Cooke, by then in Cuban exile, Kelly drew closer to the pro-Cuban Peronist Left ( Compañero , 27 August 1963). In early 1964, Kelly renamed the ALN as Alianza de Liberación Nacional, which was already recognised as a Marxist group in the follow-ing year ( Primera Plana , 4 February 1964 and 19 October 1965). Indeed, in 1964, the Alianza ’ s organ had welcomed that ‘ Perón marches towards socialism ’ and published an extensive interview with Cooke, in which he advocated a tercermundista revolution that fi rst necessitated the purging of the Catholic wing of Peronism ( Alianza , extra bulletin, June 1964). Beyond this short-lived attempt at reviving the Alianza as a pro-Cuban and Peronist organisation, the group ’ s importance in the second half of the 1960s was minimal by all accounts. A limited number of its erstwhile members, how-ever, became involved, through their participation in other groups, in the increasing political violence after 1955 (see below). In 1973, the extreme rightist elements of the ALN were revived under Queraltó to repress the insurgent Left ( Verbitsky, 1995 : 64; Gutman, 2003: 319 ), while Kelly sought to steer a moderate path on neither side of the confrontations ( Marchar , 2 October 1974).

Summarising, the Alianza distinguished itself from other nacionalista factions in several respects. Firstly, since its foundation in 1937, its aim had been to build a mass base of workers by drawing on a populist and revolutionary rhetoric of social justice. Secondly, young men were over-represented in it. Thirdly, initially it was anti-Semitic

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 362 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

and, in style and ideology, arguably fascist, two elements which dissipated in the wake of its Peronisation. Finally, in the changing ideological climate of the 1960s, its leader declared himself a Marxist and drew closer to the emergent left-wing Peronist groups, some of which attempted to follow the Cuban model of armed insurrection.

Tacuara

In several respects, the history of the second nacionalista group from which later guerrillas emerged, Tacuara, resembled the Alianza ’ s shift from right- to left-wing nationalism, although it took place at a later stage, faster and more intensely. In com-parison to the Alianza, Tacuara and its offshoots, even in their heyday of 1960 – 1963, were smaller groups.

The name Tacuara, a lance used by gauchos in the nineteenth century, indicated the group ’ s origins in nacionalismo and the strong infl uence that historical revisionism exerted over it. ‘ Tacuara ’ had already been the title of the organ of the UNES in 1945, at which point it had been the youth section of the ALN (ACPM, Mesa C, Legajo no. 75). In the late 1940s, the UNES had ceased to be the youth section of the ALN, because its leaders disagreed with the Alianza ’ s pro-Peronist line. In late 1955, Tacuara was founded by the remaining UNES members, most of whom were under eighteen years of age, in support of the nacionalista sectors of the anti-Peronist ‘ Liberating Revo-lution ’ (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 14199: 413 [1972]; Mesa R, Legajo no. 18744: 2). During its fi rst three years of existence, Tacuara was in the main composed of upper-class secondary school students from the Federal Capital, with many pupils from Catholic schools. Although an increasing number of middle-class students later entered Tacuara, its secretive character, which allowed full membership only after the fulfi lment of laborious rituals, kept numbers down ( Bardini, 2002: 33 – 34 ). Due to the offshoots that emerged after 1960 and to variations over time – partly as a result of varying legal status – it is impossible to establish precise overall numbers, but Tacuara and its various breakaways after 1960 taken together probably never had more than 1,000 active members. By 1965, after it was made illegal, overall numbers decreased to approximately 200. 5

5 Police records measured its weight in terms of the electoral results of the Unión Cívica Nacionalista (UCN), with which Tacuara had formed an alliance for elections. The UCN received votes only in the capital, altogether 4,742 in 1957 and 2,092 in 1961 (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 18744: 2). Although the American magazine Time estimated 4,000 Tacuara members in 1962 (21 September 1962), this fi gure seems exaggerated to me, as well as to other historians ( Padrón, 2006: 4 ). Without mentioning his source and which of the offspring he is counting, Rock (1993: 207) estimates 60 members in 1964. This number seems too low to me, because, based on police reports, Congress identifi ed 198 members of all Tacuara offshoots counted together in 1965, of whom 111 were under arrest. ( Diario de sesiones, Cámara de Diputados , 20 August 1965: 23 – 24; La Nación , 21 August 1965). This last number seems most realistic to me. It may have been a little higher in 1964, but certainly not much.

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 363

Argentine Nationalism

It is also diffi cult to pin down Tacuara ’ s ideology. This confusion was refl ected in a police report, in which the group was fi rst classifi ed as ‘ right-wing, with a strong tendency to extremism ’ , but later as a communist sympathiser. The main lasting common denominator was thus Tacuara ’ s ‘ sense of history ’ , which was classifi ed as ‘ revisionist ’ (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 18744: 2). Discounting the post-1960 derivatives for a moment, the ideas propagated by Tacuara ’ s mainstream remained similar from 1955 to 1965 and resembled those of the Alianza before the rise of Perón. Tacuara wanted to abolish the democratic, bourgeois and liberal order by revolutionary means, installing instead a national-syndicalist state that would reject both communism and capitalism. According to one statement, ‘ a revolution is when the Community restores the state to its function as synthesiser of “ social antagonisms ” ’ . It was therefore ‘ a historical need that the National Forces take power and return it to the service of the Common Good ’ . These aims were imbued with a cult of violence, vowing that ‘ those who shun this struggle can only be called cowards or traitors ’ ( Huella , 8 October 1963). The group ’ s leader, Alberto Ezcurra Medrano, told a journalist in 1962 that Tacuara rejected the fact that ‘ the regime incarnates materialism, negating the spiritual and permanent values of nationality ’ . Tacuara, in turn, sought to ‘ install a new order ’ that was Christian, nationalist and socialist ( García Lupo, 1962: 77 ). A Tacuara fl yer disseminated at a demonstration in 1963 stated: ‘ we throw ourselves into the struggle for God and the Fatherland. We will clean with blood what can only be cleaned with blood ’ ( Crónica , 21 November 1963). Correspondingly, from the late 1950s, the core of Tacuara members received military training (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 18744: 2).

During Tacuara ’ s fi rst fi ve years of existence, from 1955 to 1960, the anti- communist and anti-Semitic priest Julio Meinvielle, a veteran of nacionalismo who had stayed clear of Peronism, was its main intellectual mentor. In this early phase, the group adopted the Roman salute and worshipped the founder of the Spanish falange , José Antonio Primo de Rivera (ACPM, Mesa C, Legajo no. 75: 6 [1960]; Gutman, 2003: 57 – 61 ). Anti-Semitism was another main trait, which continued to be strong in all but one offshoot (e.g. La Barbarie , November 1964). In 1960, Tacuara members painted walls in the capital with swastikas in protest against Mossad ’ s capture of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 10411: 183 – 188 [1963]), and in the following year a Jewish student declared that Tacuara members had kidnapped her and tattooed her breast with a swastika ( La Nación , 25 June 1962; Senkman, 1986: 33 – 42 ). In 1964, members of the main group, under the leadership of Ezcurra Medrano, assassinated Raúl Alterman, a 28-year-old law student, for being Jewish and/or a member of the Communist Party (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 14199: 415 [1972]; La Nación , 5 April 1964). Such acts of violence had led to a presidential decree in April 1963 which outlawed Tacuara and its derivatives (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 14199: 415 [1972]).

Within Tacuara, disagreement arose over Peronism and the Cuban Revolution. In the late 1950s, inspired by Meinvielle, the still elitist Tacuara rejected the popular complexion of Peronism, earning them not only criticism from ALN activists ( Senkman, 1986: 30 – 31 ), but also Cooke ’ s recommendation to Perón to ‘ shoot the lot of them ’ ( Cooke and Perón, 1973: 203 – 204 ). The anti-populist stance, however, crumbled among most members, the fi rst unmistakable sign of which came in 1960, when Meinvielle

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 364 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

and his cohorts denounced leftist infi ltration and founded the Guardia Restauradora Nacionalista (GRN) to perpetuate a more elitist and traditionalist brand of anti- Semitic Catholicism and anti-communism (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 12459 [1963]; Gutman, 2003: 107 – 110 ). All other Tacuara branches were subsequently drawn into the orbit of Peronism. In 1961, a group led by Dardo Cabo, the nineteen-year-old son of a Peronist unionist, led a decidedly Peronist breakaway, the Movimiento Nueva Argentina (MNA). Similarly to the remainder of Tacuara, the MNA entered into relations with Peronist unionists, especially the maverick pro-Cuban Héctor Villalón, and became activists as well as members of the Juventud Peronista (JP) ( Primera Plana , 19 October 1965; Bardini, 2002: 57 – 60 ). In 1966, the MNA became widely known for kidnapping an airplane, landing on the Falklands and claiming the islands for Argentina ( Primera Plana , 4 October 1966).

The most important of the offspring with regard to later developments, however, was the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario Tacuara (MNRT), which was formally constituted in December 1962, under the leadership of Joe Baxter and José Luis Nell. Both were law students of Irish descent, 6 who had entered Tacuara in 1956 and 1958 respectively, each at the age of sixteen. As Baxter explained in the following year, the rationale behind the break with Ezcurra ’ s mainstream Tacuara was that the latter had become a para-police unit at the service of the oligarchy. The MNRT ’ s aim was instead to rely on the ‘ real forces of anti-imperialism ’ . In an astonishing balancing act, Baxter tried to reconcile his newfound sympathies with the Cuban Revolution with Tacuara ’ s legacy of anti-Semitism. He thus explained to a journalist: ‘ nobody can say that Fidel Castro is an anti-Semite. But he is a Cuban nationalist, he fi nished with the exploiters and the majority of Jews had to go ’ ( Primera Plana , 26 November 1963). Tacuara ’ s anti-Semitic legacy arguably found an outlet in the association with anti-Zionist Third World solidarity groups. At a meeting organised by the university branch of the JP, attended by several revisionist historians and the representative of the Arab League, the anti-Zionist Hussein Triki, Baxter said: ‘ We, who come from the Right, affi rm that it is necessary to leave aside old and false confrontations between students and Argentines who fi ght for national liberation ’ ( Crónica , 20 November 1963).

The splits of Tacuara were partly the result of the group ’ s modest expansion in the late 1950s. No longer a minuscule group of Catholic school students, the entry of

6 As one of the anonymous reviewers of this article has put it, the Irish dimension may be ‘ not just anecdotal ’ . Given the small size of Argentina ’ s Irish community, the inor-dinate number of Argentines of Irish origin in revolutionary nationalist circles is con-spicuous indeed: besides Baxter (who, however, was of Anglo-Irish descent) and Nell, two more leading tacuaristas , Juan Mario Collins and Nicanor D ’ Elía Cavanagh, were of Irish origin. So were Nell ’ s partner, Lucía Cullen (fi rst FAP, later Montoneros), Walsh (see below) and, on the paternal side, Cooke and Kelly. Another example was Norma Kennedy (see below). This over-representation of Irish Argentines may well have to do with similarities between Argentine and Irish nationalism, which both allowed for both left- and right-wing currents and drew on anti-British feelings and Catholicism. Interestingly, the other over-represented group in these circles were Argentines of Croatian descent (e.g. Tomislav Rivaric (see below), Daniel Zverko (fi rst GRN, then Montoneros), Jaroslav Dazac (ALN) and the Peronist nacionalista politician Oscar Ivanissevich).

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 365

Argentine Nationalism

middle- and lower-middle-class adolescents ( García Lupo, 1962: 72 – 73 ) as well as the geographical expansion beyond the capital and Greater Buenos Aires recommended an opening towards other revolutionary activists, in the main the JP and the youth federa-tion of the Communist Party. Baxter ’ s section was active and soon successful in estab-lishing close contacts with both these groups, which facilitated the acquisition of arms (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 14199: 416 [1972]; Legajo no. 18744: 7). The MNRT ’ s penchant for armed action fi rst came to the fore in August 1963, when a commando assaulted a security van carrying the wages of bank employees, killing two guards, to raise funds for future activities (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 18744: 8; La Nación , 5 April 1964; Bardini, 2002: 25 – 26 ). After this, contacts with the JP became closer still, in particular between Nell and the JP leader Envar El Kadri ( Anguita and Caparrós, 1997: 108 – 109 ). This alliance was refl ected in the foundation of the Movimiento Revolucionario Peronista (MRP) in August 1964, which published a communiqué vowing to ‘ safeguard national sovereignty to the last instance ’ and promising the ‘ total elimination of the parasitic social classes that serve international fi nance capital ’ ( Cristianismo y Revolución , no. 6 – 7, April 1968: 5; Compañero , 8 September 1964). In the same year, the MNRT issued a joint statement with CONDOR, a group of Marxist – Peronist intellectuals. Imbued with anti-intellectualism and anti-liberalism, the document claimed that ‘ Peronism is a national mass movement that develops its own revolutionary vanguard ’ , which would lead to ‘ revolution in Argentina, which can only happen through the massive mobilisation of the Argentine people in war against the system ’ . The language drew on Marxism, which was embraced as a means to ‘ resolve in [ … ] practice the problem of our semi-colonial dependency ’ , concluding that ‘ no one who calls himself a Marxist can be outside Peronism ’ (in Baschetti, 1997: 331 – 344 ). By early 1964, the MNRT was already publicly identifi ed as a Peronist and Marxist group and a police raid on MNRT premises in September found ‘ numerous books, mostly about Marxist doctrine ’ ( Primera Plana , 10 March 1964; ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 14199: 417 [1972]). In 1965, Congress tellingly discussed Tacuara as an instance of ‘ communist infi ltration ’ rather than as a problem of fascism ( Diario de sesiones, Cámara de Diputados , 20 August 1965: 23 – 24; La Nación , 21 August 1965). Similarly to the Alianza, with whose remaining splinter groups it had by then also established links (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 18744: 7), the MNRT had thus become a Marxist – Peronist group that advocated Third World liberation. And like the Alianza twenty years before, the MNRT was, even though far smaller, a group consisting predominantly of men around the age of twenty ( La Nación , 5 April 1964).

By the mid-1960s, Tacuara was in the process of disintegrating. After the violent actions of the early 1960s, half of its members were in prison, while many of those who remained free, particularly in the case of the MNRT, affi liated themselves to the JP (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 14199: 416 [1972]; La Nación , 21 August 1965). The principal leaders were in hiding and some, like Baxter and Nell, spent much of the period between 1964 and 1968 abroad (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 18744: 8). Some mainstream tacuaristas , in the meantime, became police informants in support of the military coup of 1966 ( Primera Plana , 19 July 1966). Two years later, Tacuara was fi nally disbanded. The following trajectory of erstwhile Tacuara members again resembled those of some ALN activists: some ended up with the vigilante death squads and the

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 366 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

dictatorship of the 1970s, others pursued a revolutionary career in the emerging guerrilla groups. Former GRN members were known to be linked to extreme rightist para-military groups ( Moyano, 1995: 79 ), which also recruited from the MNA, as in the case of Alejandro Giovenco ( Verbitsky, 1995: 105 ). When, upon Perón ’ s return to Argentina in 1973, right-wing Peronists opened fi re on the Montoneros, former MNRT militants were on both sides of the ensuing exchange of gunfi re ( Gutman, 2003: 278 – 283 ). Yet what matters for the moment are the links between the ALN and Tacuara and the guerrilla groups of the 1960s and 1970s.

Nacionalismo and the Left-Wing Guerrillas

The question of links between the nationalist Right and the guerrillas is highly conten-tious. Scholars have focused on either the rightist groups up to roughly 1945 or on the emergence of the left-wing guerrillas in the late 1960s. Typically, historians of the 1930s, such as Alberto Spektorowski, have maintained that it is essential to understand nacionalismo as a background to guerrilla warfare because the Montoneros ’ demand for a socialismo nacional marked continuities with interwar fascism and that ‘ it is thus not surprising that the Montoneros recruited their rank and fi le particularly from sectors defi ned as nationalist Catholics ’ (2003: 209). Conversely, those who have ana-lysed guerrilla movements have usually approached the issue of nationalism from the question of how important the input of earlier nacionalistas was for the development of the armed organisations of the 1970s (e.g. Gillespie, 1982: 48 – 52 ). This focus on the pre-1945 and the post-1969 periods at the expense of research on the years in between is probably due to numbers: sizeable nacionalista organisations existed until they were overshadowed or co-opted by Perón, while guerrilla groups grew exponentially after the student-worker protest in Córdoba in 1969, boasting more than 5,000 armed combatants in 1974 ( Moyano, 1995: 2 ). Throughout the 1960s, in turn, militant groups were numerically small and the guerrillas of that decade made only a limited military impact. It is important to bear in mind these overall numbers and the chronological framework when assessing the importance of the ALN and Tacuara for the guerrillas. Quantitatively, if measured against the mighty guerrillas of the mid-1970s, ALN and Tacuara were unlikely to make a great impact: the ALN, because the many members of its heyday were no longer in the age group apposite for guerrilla struggle; Tacuara because it had been a relatively small group to begin with.

Debate on the input of nacionalismo has been further complicated by the literature ’ s focus on the Montoneros. This emphasis is perfectly understandable. Firstly, the Montoneros, a Peronist organisation that rose out of Catholic networks in the late 1960s, were the most powerful organisation by the time of Perón ’ s return from exile in 1973. Their dominance rested on perhaps 2,000 armed combatants by 1974, but most of all on their organic link to the JP, which allowed them to mobilise militants in their hundred thousands. Secondly, they were also the most colourful organisation, with their Peronist mystics and symbolic operations, such as the kidnapping and assas-sination of the military general who had presided over the anti-Peronist military regime of 1955 – 1958, which instantly won them fame in 1970. However, even after that it

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 367

Argentine Nationalism

was by no means clear that the Montoneros would become the most important guerrillas. In fact, in late 1970, they had to seek the protection of the by then most powerful organisation, the Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas (FAP) ( Moyano, 1995: 25 ), large parts of which in turn later joined the Montoneros. In military terms, the non-Peronist Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP), a guerrilla group of Trotskyist extraction, was stronger than the Montoneros.

While the larger guerrilla groups besides the Montoneros are increasingly researched, there were various precedents in the period from 1955 to 1968 that are less well known, perhaps because all of them seemed to be soon defeated. The fi rst Argentine guerrilla group was set up immediately after the Cuban Revolution. The Uturuncos ( ‘ tiger-men ’ in Quechua) were a Peronist guerrilla group of approximately 50 fi ghters in rural Tucumán, ideologically guided by Cooke ( Salas, 2003 ). The MNRT may itself be called Argentina ’ s fi rst urban guerrilla group ( Gutman, 2003 ). Next, in 1963, the journalist Jorge Ricardo Masetti led a Guevarist foco in the province of Salta, called Ejército Guerrillero del Pueblo (EGP) ( Rot, 2000 ). Other groups, such as the anti- imperialist Frente Revolucionario Indoamericano Popular (FRIP), which was founded in 1961 and later evolved into the ERP, and the Peronist Fuerzas Armadas de la Revolución Nacional (FARN), founded in 1963, also formed part of a growing political spectrum that advocated armed struggle in the 1960s. Former or present militants of the ALN and Tacuara were an integral part of this spectrum.

Fascination with the Montoneros meant that the most frequently cited examples of links between left-wing guerrillas and nacionalismo were two fi gures who were deci-sively involved in setting up the Montoneros in 1969. According to many sources, the Montoneros ’ co-founders Fernando Abal Medina and Gustavo Ramus had been Tacuara activists ( Gillespie, 1982 : 48 – 52; Moyano, 1995: 187 ). More recently, it has been suggested that this information snowballed from a report in the leading Montonero newspaper El Descamisado in 1973, where homage to the two claimed that they had been members of Tacuara ( Lanusse, 2005: 35 ). The most complete journalistic investiga-tion of Tacuara thus far ( Gutman, 2003: 95 ) has indeed found nothing to support this claim, nor have I come across any pre-1973 source to confi rm it. 7 Yet, even if untrue, the claim is anything but absurd, as there were in fact numerous examples of revolu-tionary guerrillas or members of collateral groups who in their adolescence had been

7 Both Fernando Abal Medina and Ramus died in a confrontation with police in September 1970. While I share Lanusse ’ s scepticism, it is worth noting that Baschetti (1995: 38) specifi cally mentions Ramus ’ s short-term membership of the GRN, which is not men-tioned in the report in El Descamisado (no. 17, 11 September 1973). This suggests that Baschetti, even though he does not disclose it, must have relied on a source other than El Descamisado , Gillespie, etc. Gutman (2003 : 306 – 307) clarifi es that Juan Manuel Abal Medina (see Fig. 1 for more information on him) denied that his brother Fernando had ever been a Tacuara member. But Juan Manuel also denied that he had been a member himself, which Gutman (2003: 306 – 307) convincingly dismisses as untrue. If not members of the original Tacuara, Beraza (2005: 265 – 267) shows that both Abal Medinas were activists of the nacionalista Right as late as 1967. The case exemplifi es the diffi culties of research in this area. Since the police reports used for this article do not mention names, the gaps have to be fi lled by inferring from other sources, which in turn have often relied on oral history and occasionally contradict each other.

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 368 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

members of the ALN and especially Tacuara. The newspaper El Descamisado itself, for example, was directed by Dardo Cabo.

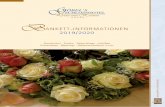

An overview map of the main links, which are well documented, is given in Fig. 1. Although not giving names, apart from Antonio Arroyo and Eduardo Pedrotti, the most complete investigation of the Uturuncos so far has found that a signifi cant propor tion of its approximately 50 fi ghters came from the ALN ( Salas, 2003: 92 – 97 ). The founder of the FRIP, Francisco René Santucho, had been a member of the ALN in the mid-1940s ( Seoane, 2003: 31 ) and so had the EGP leader Masetti, in 1945 – 1946, at the age of fi fteen ( Rot, 2000: 17 – 32 ). There, Masetti had met Rodolfo Walsh, of the same age, who would later become a Montonero ( McCaughan, 2001: 36 ). In these two cases, the time span that lay between their adolescent activism and their later participation in guerrillas may be too long for their earlier involvement in nacionalismo to be signifi cant. However, in the case of Tacuara there were even more such links, with less time passing between the experiences. After they had helped to build up the Uruguayan Tupamaros, Baxter went on to become a co-founder of the Trotskyist ERP and later the leader of its anti-Peronist ‘ Red Faction ’ ( Gutman, 2003 : 271 – 275; Seoane, 2003: 314 ), while Nell became a prominent Montonero ( Gutman, 2003: 277 ). 8 Rodolfo Galimberti, a JP leader from a wealthy porteño background and, like Nell, an important Montonero from the early 1970s, had also begun his career in politics in Tacuara, at the age of sixteen ( La Nación , 13 February 2002). Dardo Cabo, before becoming a Montoneros offi cer, had been a leading organiser of the small Catholic Peronist guerrilla group, Descamisados, which joined the Montoneros in 1972 ( Moyano, 1995 : 108; Bardini, 2002: 64 ). Most signifi -cantly of all, after having been released from prison, the majority of the MNRT com-mandos who had seized the bank employees ’ money in 1963 were involved in setting up and leading the Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas (FAP) in 1967/1968, by then the most im-portant guerrilla group, large parts of which later joined forces with the Montoneros ( Pérez, 2002 : 49 – 54; Gutman, 2003: 276 ). 9 In an interview with the Cuban newspaper Granma , FAP activists explicitly mentioned the MNRT as an antecedent of their strug-gle ( Cristianismo y Revolución , no. 28, April 1971: 78). If collateral groups are included, the links become even more bewildering and the list of names and acronyms potentially endless. The details of these are hardly necessary to convey the general point: out of those who had joined Tacuara in their adolescence, a signifi cant number pursued careers as armed revolutionaries, especially (but not only) in Peronist groups, which placed special emphasis on nationalism.

8 Nell had been arrested in Uruguay and was going to be extradited to Argentina, against which Cooke campaigned ( Che Compañero , June 1968), but he fl ed prison together with other Tupamaros in 1971. After having been left paralysed at the Ezeiza shootout, upon Perón ’ s return he killed himself in 1974. Baxter died in a plane crash at Paris ’ s Orly airport, allegedly with 40 million dollars in his baggage for the by then little known Sandinistas ( La Opinión , 14 July 1973).

9 The problem with names and complete lists of militants applies again, but I could at least ascertain the following names of people who passed from the MNRT to the FAP, on the basis of more than one source each: Jorge Cataldo (co-founder of the FAP), Rubén Rodríguez (co-founder of the FAP), Jorge Caffatti, Carlos Arbelos, Alfredo Roca, Horacio Rossi, Amílcar Fidanza, Norberto Espina and Tomislav Rivaric.

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 369

Argentine Nationalism

Ideologically, imagery that was partly derived from nacionalismo , especially historical revisionism, also pervaded the discourse of the left-wing guerrillas. Again, this was clearest in the case of Peronists, as the name Montoneros, referring to nineteenth- century gaucho militias, suggested. In their fi rst public communiqué, the Montoneros portrayed themselves as the culmination of a historical continuity, in which there were ‘ two great political cur-rents: on the one hand, the liberal Oligarchy, clearly anti- national and bound to sell the fatherland, on the other, the People, identifi ed with the defence of its interests, which are the interests of the Nation, against imperialist attacks in all historical circumstances ’ ( Cristianismo y Revolución , no. 26, November – December 1970: 11). Exaltations of the federal caudillos and Rosas were central to the publications of the JP in the early 1960s ( Trinchera , October 1960) as well as to the mouthpieces of the so-called revolutionary tendency of Peronism that emerged a decade later (e.g. Militancia , 28 June 1973). Revisionist authors were also obligatory reading matter for FRIP ( Pozzi, 2004: 45 ) – which unsurprisingly also had contacts with the MNRT in the mid-1960s ( La Nación , 5 April 1964) and the later Guevarist Masetti ( Rot, 2000: 19 – 22 ).

This is not to say that the guerrilla groups of the 1970s were dominated by men from nacionalista backgrounds. Nor does the history of Argentine nationalism explain the political violence after 1969. If the phenomenon of the guerrillas (as well as the paramilitary death squads) is analysed quantitatively, as in recent studies, the impact of Tacuara, let alone the ALN, begins to look less weighty. For example, of the fi fteen members of the small EGP foco in 1964 for whom Rot (2000: 185 – 190) has recorded previous political activism thirteen were Communists. In the case of the much bigger ERP, the majority of those who had been politically active around the mid-1960s came from Marxist groupings, too, while, as ERP numbers grew in the early 1970s, few of the new recruits, especially women, had any previous political experience ( Pozzi, 2004: 74 ). Recent studies of the emergence of the Montoneros ( Donatello, 2003; Lanusse, 2005 ) have further underlined the overwhelming importance of left-wing Catholic networks in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, rather than nacionalista groups, in this process. Moreover, in order to explain the growth of armed struggle in Argentina, sociological and political factors have to be taken into account which go beyond the internal ideological development of groups such as the ALN and Tacuara. As Waldmann (1982) has argued, if violence had been a potential or real means to achieve political goals in the eyes of many actors – from the Armed Forces to revolutionary groups of diverse persuasions – long before this became a widespread practice after 1969, then, rather than asking for the reasons that ‘ caused ’ the violence, it may be more promising to look for the disappearance of factors that had previously hindered the massive rise of political violence. Here, the reduction of the previous multiplicity of axes along which politics had been negotiated in the wake of the coup of 1966 appears as a main factor.

However, rather than trying to explain the rise of political violence, the aim here is to account for the transitions in Argentine nationalism that occurred during the 1960s. To understand this, groups such as the ALN and Tacuara were crucial. The most striking feature of the history of these groups in the 1960s is the extent to which they were part of a sometimes baffl ing political mobility. For example, one of the few women involved in armed activities before 1969, Amanda Peralta, was at different times a member of almost all the armed nationalist groups: the Uturuncos, FARN,

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 370 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

Tacuara and the FAP ( Pérez, 2002: 55 ). While by and large the movement was from rightist nacionalismo , sometimes fascism, to left-wing anti-imperialism, the reverse trajectory was by no means unheard of. Former members of the ‘ left-wing ’ MNRT, such as Luis Alfredo Zarattini, were later linked to right-wing death squads and helped to implement state terror after the coup of 1976 ( Bardini, 2002 : 141; Gutman, 2003: 279 ). Norma Kennedy ’ s political career took her from the Communist Party in the early 1950s to the right-wing Peronist Comando de Organización, the group that opened fi re on the Montoneros when Perón fl ew into Buenos Aires in June 1973 ( Verbitsky, 1995: 95 – 100 ). What really needs explanation, then, is the ease and swift-ness with which right- and left-wing nationalism were communicating. Here, the history of the ALN and Tacuara stand for the broader developments.

1

2

3

4

5 8 9

156 7 10

14 17

6

1318

11 12 19

7

16

Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista (1937/43)Peronist from 1946/53 / pro-Cuban sector under Kelly from 63

L: Queraltó (37-53) / Kelly (53-late 60s)M: 11,000-50,000 in 1945 / probably less than 2,000 in 1956

Tacuara (1955)L: Ezcurra Uriburu (55-

63)M: 200-4,000 in 1960(probably less than

1,000)

Uturuncos (1959)Peronist, pro-Cuban rural guerrilla

L: Mena / M: c.50

GuardiaRestauradoraNacionalista

(1960)Anti-Semitic,

CatholicL: Meinvielle

M: less than 60in 1965

Movimiento NuevaArgentina (1961)

PeronistL: Cabo

M: less than 60 in 1965

Movimiento Nacionalista Revo-lucionario Tacuara (1962)

Peronist, pro-CubanL: Baxter / Nell

M: less than 60 in 1964

Juventud Peronista (59/60)L: El Kadri / Spina / G. Rearte

M:c.50 in 1960/ manythousands in early 70s when

front org. of Montoneros

Ejército Guerrillero delPueblo (1963)

GuevaristL: Massetti / M: 49

Extreme right in 1973-76(Triple A, Peronist right in

Ezeiza etc.)

Fuerzas ArmadasPeronistas (1967)

L: Caride, El Kadri etc.M: 400 in 1974Ejército Revolucionario del

Pueblo (1969)Marxist, non-Peronist

L: MR SantuchoM: approx. 3,000 in 1974

FrenteIndoamericanoPopular (1961)

TrotskyistL: FR Santucho

Montoneros (1969)Peronist

L: severalM: approx. 70 in 1970; 2,000 (or more?)

in 1974Juventud Peronista organically linked

after 1971

Tupamaros (URU)

Unión Nacionalista de EstudiantesSecundarios (1935)

Youth branch of Legión CívicaL: Queraltó

Unión Cívica Na-cionalista (1948)

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 371

Argentine Nationalism

Figure 1. Connections between Argentine nationalist groups Note: In brackets: year of foundation. L: Leader(s). M: Approximate number of members. A broad black arrow indicates that the input from the group where the arrow originates was highly signifi cant for the subsequent group (usually for small groups founded before the mid-1960s), or that a signifi cant number of militants of the earlier group went on to participate in the later group (usually after the mid-1960s (e.g. MNRT ! FAP)). Lines without arrows indicate connections between the groups, without militants passing from one to the other. The stronger the line, the more relevant the connection.

1. FRIP leader Francisco René Santucho from ALN. 2. EGP leader Jorge Ricardo Masetti from ALN. 3. Signifi cant proportion of Uturuncos from ALN (e.g. Antonio Arroyo, Eduardo Pedrotti).

Arroyo later member of MNA. 4. Political links between Uturuncos and future MNRT member Amílcar Fidanza. 5. FRIP, which had political links with MNRT, later became a constituent part in foundation of ERP. 6. Former MNRT leader Joe Baxter fi rst to Tupamaros, then to ERP. Former MNRT member

Ricardo Viera to ERP. 7. Former MNRT leader José Luis Nell fi rst to Tupamaros, then to Montoneros. 8. Former Uturuncos José Luis Rojas and Amanda Peralta to FAP (Peralta also temporarily in Tacuara). 9. FAP largely led by leaders of the early JP, e.g. Carlos Caride and Envar El Kadri. 10. Majority of remaining MNRT to FAP, e.g. Carlos Arbelos, Jorge Caffatti, Jorge Cataldo, Norberto

Espina, Amílcar Fidanza, Tomislav Rivaric, Alfredo Roca, Rubén Rodríguez, Horacio Rossi. 11. Large parts of FAP (the so-called ‘ obscure faction ’ ) joined the Montoneros in 1972. The other

FAP faction (called ‘ Comando Nacional ’ ), to which most former MNRT members belonged, joined the ERP in 1974.

12. JP became front organisation of Montoneros around 1971/1972. 13. E.g. former MNRT member Luis Alfredo Zarattini involved in extreme right after 1973. 14. Former MNA leader Dardo Cabo to Montoneros, via Descamisados. 15. E.g. former MNA members Alejandro Giovenco, Américo Rial and Edmundo Calabró to

extreme Peronist right. 16. Former GRN member Juan Manuel Abal Medina became secretary general of Peronist

Movement in 1972. 17. Former GRN members Rodolfo Galimberti and Daniel Zverko to JP/Montoneros. Montoneros

co-founders Gustavo Ramus and Fernando Abal Medina also formerly GRN? 18. Montonero Rodolfo Walsh formerly ALN. 19. Juan Queraltó re-founded ALN in 1973 to assist in right-wing repression.

List of acronyms: AJN: Alianza de la Juventud Nacionalista ALN: Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista FORJA: Fuerza de Orientación Radical de la Joven Argentina EGP: Ejército Guerrillero del Pueblo ERP: Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo FAP: Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas FARN: Fuerzas Armadas de la Revolución Nacional FRIP: Frente Revolucionario Indoamericano Popular GRN: Guardia Restauradora Nacionalista JP: Juventud Peronista MNA: Movimiento Nueva Argentina MNRT: Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario Tacuara MRP: Movimiento Revolucionario Peronista UNES: Unión Nacionalista de Estudiantes Secundarios

In all cases, international events played a key role for the formulation of an armed revolutionary strategy, while Peronism provided by far the most important sphere of sociability to link Right and Left. Let us consider the international dimension fi rst.

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 372 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

Remarkably, after the fi rst step of Peronisation, the acceptance of Marxism among both the ALN and a signifi cant faction of Tacuara can be dated quite precisely to the years from 1960 to 1964. This points to the overwhelming impact of the Cuban Revolution, closely followed in importance by the Algerian war of independence. It was no coincidence that the fi rst Argentine guerrilla attempt was set up in December 1959 and that Cooke, who spent most of the 1960s until his early death in 1968 in Cuba and fought in the Bay of Pigs ( Baschetti, 1999 ), was so crucial in the develop-ment of the Uturuncos ( Salas, 2003 : 52 – 53, 124).

One reason why the history of the embryonic guerrilla groups has remained such a murky issue in scholarship seems to be that so many of them spent signifi cant parts of the 1960s outside Argentina. For example, long before he sought to emulate Che Guevara in the mountains of Salta, Masetti had interviewed his idol in the Sierra Maestra in 1958, been in charge of the revolutionary Cuban news agency Prensa Latina, where he worked with Walsh, and received military training in Algeria. Both this train-ing and the EGP were, to a great extent, fi nanced by the Cubans ( Anderson, 1997 : 308 – 309, 552 – 555; Rot, 2000 : 47 – 70, 125 – 135). The leaders of both FARN and FAP had been in Cuba, too, before setting up their groups back in Argentina ( Pérez, 2002 : 38, 55). Baxter ’ s itinerary was the most puzzling: probably organised by the Argentine branch of the Arab League, he left Argentina in January 1964 for Nasser ’ s Egypt, went on to Algeria and Czechoslovakia, received military training in China and fought for the Vietcong before attending the IV International in Paris in 1968, where he met the future leader of the ERP (ACPM, Mesa R, Legajo no. 14199: 418 – 419 [1972]; Seoane, 2003: 314 ). At least ten of the future top leaders of the Montoneros, the FAP and the ERP received military and ideological training in Cuba in the mid-to-late 1960s ( Moyano, 1995: 134 ). Such contacts with foreign revolutionaries, a list of which could almost be extended ad infi nitum , together with the enormous prestige that the Cuban Revolu-tion enjoyed among virtually all Argentine leftist intellectuals ( Sigal, 2002: 163 – 172 ), testifi ed to the impact of Cuba in the merger of Marxism and nationalism in Argentina. Even the revisionist historian Rosa, formerly a self-confessed fascist, declared his sympathy for the bearded revolutionaries after a visit to the island in 1962 ( 18 de Marzo , 5 February 1962).

However, as the centrality of the JP in Fig. 1 shows, there was also a domestic chan-nel of communication between the different forms of nationalism: Peronism. In the case of both the ALN and Tacuara, their Peronisation was the decisive activator of ideological mobility. Virtually all of the militants who passed from one form of nationalism to another were temporarily involved in Peronist groups. This also applied to examples of the left-to-right movement like Kennedy, who edited a hard-line Peronist newspaper during the late 1950s ( El 17 ) and was a member of the JP in the early 1960s ( Gutman, 2003: 172 ). Groups such as the Montoneros, whose fi rst operations were clearly designed to enhance their credibility as part of the Peronist movement, under-stood very well that their future was inextricably bound up with Peronism. As Moyano (1995: 25) has remarked, the Montoneros ’ key ‘ stroke of genius ’ , which ensured their future success, was their seizing control of the JP, which they soon turned into a front organisation of their own. While the history of the ALN and Tacuara and the trajectories of their members cannot in themselves explain the phenomenon of political

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 373

Argentine Nationalism

violence in Argentina, and while their quantitative importance for the emergence of guerrilla groups should not be overestimated, their involvement nonetheless remains qualitatively signifi cant from the perspective of the transformation of Argentine nationalism. With regard to this, the history of ALN and Tacuara members allows for several points in conclusion.

Conclusion

The two nacionalista groups in which later guerrillas had their fi rst political experi-ence showed remarkable similarities. Within nacionalismo as a whole, they stood out for their radicalism, revolutionary fervour and advocacy of violence, in contrast to what Buchrucker (1987: 116 – 257) has called the ‘ restorative ’ trends of authoritarian nationalism. This was particularly true for the Alianza, but also for those factions of Tacuara (especially the MNRT) from which later guerrillas came. Both groups further-more underwent similar transformations. Initially, they accentuated their populism, which in the case of the ALN went hand in hand with seeking a genuine mass ap-peal by adopting social justice and workers ’ rights as their demands, a development matched, albeit less successfully, by the Peronisation of large parts of Tacuara. In both cases, this arguably led to these groups entering a fascist stage, if fascism is understood as a revolutionary phenomenon that fundamentally rejects the ideas of liberty, democ-racy, reason and peace, and advocates the creation of a new communitarian conscious-ness that expresses the destiny of the nation, in opposition to corrupting ‘ parasites ’ ( Burrin, 2000: 49 – 71 ). The fact that Tacuara in particular failed to develop a mass appeal and that its members insisted on taking their inspiration from the Spanish falange rather than directly from Italian fascism does not contradict this and the group has rightly been referred to as at least ‘ neo-fascist ’ in the literature (e.g. Rouquié, 1978: 579 ). Another parallel, however, was that both groups, after having drawn closer to Peronism, began to stress the one main element that had little to do with fascism; namely, anti-imperialism. Finally, in both groups, young men between fi fteen and 25 years of age were over-represented.

As regards collective biographies, the common pattern of the later guerrillas with earlier nacionalista militancy was that they had joined the ALN and Tacuara in their teens. In particular in the case of the ALN this raises doubts as to how seriously this involvement should be taken. Walsh and Masetti had left the ALN long before they were twenty, the time span that passed between then and their later guerrilla activities was very long and, in any case, the ALN was a relatively large organisation in the mid-1940s, so that the signifi cance of the membership of these two fi gures should not be overestimated. As for the participation of ALN activists among the Uturuncos, it has to be borne in mind that the Alianza was by then a relatively ‘ normal ’ grouping of the Peronist resistance. Tacuara, hence, was more relevant as a stage of militancy in the unfolding of political violence in the 1970s. In contrast to the Alianza, a large proportion of former members of the small Tacuara later pursued careers entangled with political violence, on both sides of the divide. Again, the common biographical pattern of fi gures like Baxter, Nell, Cabo and the MNRT and later FAP fi ghters was

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 374 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

that they were less than twenty years old when they entered Tacuara. This probably heightened the volatility of these groups and facilitated the impact of broader processes on their ideological development.

There were two main factors that allowed for the passage between different forms of nationalism. The fi rst one was Peronism. This raises questions about the nature of populist discourse. The argument that Peronism did not derive its power from precise ideological defi nitions, but rather from its nature as a broad church, has almost become a cliché, but it is worth bearing in mind here. As Laclau has repeatedly stressed (1977: 143 – 198, 2005), it would be futile to seek to defi ne populist discourse on the basis of a coherent set of ideological points. According to Sigal and Verón (2003: 21) , the fact that Peronism ’ s ‘ historical continuity and its discursive coherence is not based on the permanence of certain contents ’ lent itself to peculiar ways of discursively constructing the political sphere, in particular during the unstable political stalemate after 1955. The extraordinary clout of Peronism (strengthened rather than weakened as a result of its proscription), Laclau argues, lay in its ability to harness disparate needs and demands in an unlimited chain of symbolic equivalences. After 1955, Peronism ’ s ‘ very success to construct [such a chain] led to the subversion of the principle of equivalence as such ’ , according to Laclau. As a result, Perón ’ s ‘ word was indispensable in giving symbolic unity to all those disparate struggles. Thus his word had to operate as a signifi er with only weak links to particular signifi eds ’ , leading Laclau to label Peronism after 1955 an ‘ empty signifi er ’ (2005: 214 – 216). Perón was quick to realise the political potential inherent in this situation. He therefore refused to move unmistakably against any of the ideologically inchoate parts of his movement, before an arbitration became inevitable in 1973. As Sigal and Verón have shown, Perón ’ s strategy of interpretable silence reinforced a key trait of the discursive construction of Peronism, namely that it ‘ is not one political position among others, [but] by defi nition a trans-political entity ’ (2003: 128). As I have argued elsewhere ( Goebel, 2006: 128 – 130 ), the centrality of revisionist historical narratives among nationalist and populist revolutionaries at the expense of programmatic precision in the present was a symptom of this constellation in Argentine populist discourse, too. The importance of these historical narratives among most of the groups analysed here and the crucial symbolic position of Peronism at the centre of their trajectories suggest that the nature of Peronism as an ‘ empty signifi er ’ was a cardinal factor in the mutations of Argentine nationalism.

The second driving force for changes in Argentine nationalism was that of interna-tional events, which strongly resonated among Argentine intellectuals. International developments are the most persuasive reason to explain why, despite isolated examples to the contrary, the general movement of nationalism in Argentina swung to the Left in this period. As Sigal (2002: 164) has argued, ‘ the Cuban Revolution provided the necessary lever to open spaces of communication between Marxists and nationalists. Cuba constructed a bridge between the Left, nationalism and Peronism ’ . Even though there were isolated attempts among intellectuals to construct such bridges in the years before 1959, such as a short-lived monthly periodical in 1957, tellingly entitled Columnas del nacionalismo marxista de liberación nacional , their impact would have been negligible without the stimulus of the Cuban model. Both the history of the ALN and Tacuara in the early 1960s underline this transnational dimension in the

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 375

Argentine Nationalism

transforma tion of Argentine nationalism from Right to Left. Once this move was completed around 1970, the content of these groups ’ communiqués differed less from the Latin American tercermundista mainstream than one might expect in the light of such antece dents. The newly gained hegemony of this discourse of left-wing national-ism then obscured the fact that in Argentina the blending of Marxism and nationalism was historically less natural and more contingent than the New Left ’ s worldview made it appear.

References

ACPM (Archivo de la Comisión Provincial por la Memoria), formerly Dirección de Inteligencia de la Policía de la Provincia de Buenos Aires. La Plata, Unpublished reports .

Alianza (1946 and 1961 – 1964) Buenos Aires . Anderson , J. L . ( 1997 ) Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life . Bantam Books : New York . Angell , A . ( 1994 ) ‘ The Left in Latin America since c. 1920 ’ , in L. Bethell ( ed .) The

Cambridge History of Latin America . Cambridge University Press : Cambridge , 163 – 232 .

Anguita , E. and Caparrós , M . ( 1997 ) La voluntad: una historia de la militancia revolucionaria en Argentina, 1966 – 1973 , Vol. 1 . Norma : Buenos Aires .

Azul y Blanco (1959) Buenos Aires . Bardini , R . ( 2002 ) Tacuara: la pólvora y la sangre . Oceano : Mexico City . Baschetti , R . ( ed .) ( 1995 ) De la guerrilla peronista al gobierno popular: documentos 1970 –

1973 . La Campana : La Plata . Baschetti , R . ( ed .) ( 1997 ) Documentos de la resistencia peronista, 1955 – 1970 . La Campana :

La Plata . Baschetti , R . ( 1999 ) ‘ John William Cooke: una historia de vida y lucha ’ , in M. Mazzeo ( ed .)

Cooke, de vuelta: el gran descartado de la historia Argentina . La Rosa Blindada : Buenos Aires , 12 – 26 .

Beraza , L. F . ( 2005 ) Nacionalistas: trayectoria de un grupo polémico (1927 – 1983) . Cán-taro : Buenos Aires .

Buchrucker , C . ( 1987 ) Nacionalismo y peronismo: la Argentina en la crisis ideológica mundial (1927 – 1955) . Sudamericana : Buenos Aires .

Burrin , P . ( 2000 ) Fascisme, nazisme, autoritarisme . Éditions du Seuil : Paris . Canton , D . ( 1968 ) Materiales para el estudio de la sociología política en la Argentina .

Instituto Torcuato di Tella : Buenos Aires . Compañero (1963 – 1964) Buenos Aires . Cooke , J. W. and Perón , J. D . ( 1973 ) Correspondencia, 2 vols. Gránica: Buenos Aires . Cristianismo y Revolución (1966 – 1971) Buenos Aires . Crónica (1963) Buenos Aires . De Dios , H . ( 1984 ) Kelly cuenta todo . Atlántida : Buenos Aires . Diario de sesiones, Cámara de Diputados de la Nación ( 1965 ) 20 August, 23–24 . Dolkart , R . ( 1993 ) ‘ The Right in the Década Infame, 1930 – 43 ’ , in S. McGee Deutsch and

R. Dolkart ( eds. ) The Argentine Right: Its History and Intellectual Origins, 1910 to the Present . Scholarly Resources : Wilmington , 65 – 98 .

Doll , R . ( 1939 ) Acerca de una política nacional . Difusión : Buenos Aires . Donatello , L. M . ( 2003 ) ‘ Religión y política: las redes sociales del catolicismo post-conciliar

y los Montoneros, 1966 – 1973 ’ . Estudios sociales 24 : 89 – 112 . El Descamisado (1973) Buenos Aires . García Lupo , R . ( 1962 ) ‘ Diálogo con los jóvenes fascistas ’ , in R. García Lupo ( ed .) La

rebelión de los Generales . Proceso : Buenos Aires , 71 – 79 . Gillespie , R . ( 1982 ) Soldiers of Perón: Argentina ’ s Montoneros . Clarendon Press : Oxford .

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American Studies 376 Bulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3

Michael Goebel

Goebel , M . ( 2006 ) Argentina ’ s Partisan Past: Nationalism, Peronism and Historiography, 1955 – 76 . Unpublished doctoral dissertation , University of London , London .

Gurucharri , E . ( 2001 ) Un militar entre obreros y guerrilleros . Colihue : Buenos Aires . Gutman , D . ( 2003 ) Tacuara: historia de la primera guerrilla urbana argentina . Vergara :

Buenos Aires . Halperin Donghi , T . ( 1999 ) ‘ Argentines Ponder the Burden of the Past ’ , in J. Adelman ( ed .)

Colonial Legacies: The Problem of Persistence in Latin American History . Routledge : New York and London , 151 – 173 .

Hernández Arregui , J. J . ( 1960 ) La formación de la conciencia nacional (1930 – 1960) . Hachea : Buenos Aires .

Hilb , C. and Lutzky , D . ( 1984 ) La nueva izquierda Argentina, 1960 – 1980: política y violencia . Centro Editor : Buenos Aires .

Huella (1963) La Plata . Ibarguren , C. , Jr . ( 1971 ) Interview by Luis Alberto Romero, 15 July 1971, Archivo de

Historia Oral, Instituto Torcuato di Tella, Buenos Aires . De Imaz , J. L . ( 1977 ) Promediados de los cuarenta: no pesa la mochila . Sudamericana :

Buenos Aires . Irazusta , R. and Irazusta , J . ( 1982 ) La Argentina y el imperialismo británico: los eslabones

de una cadena, 1806 – 1933 . Independencia : Buenos Aires [1934] . Klein , M . ( 2001 ) ‘ Argentine Nacionalismo before Perón: The Case of the Alianza de la

Juventud Nacionalista, 1937 – c.1943 ’ . Bulletin of Latin American Research 20 ( 1 ): 102 – 121 .

Klein , M . ( 2002 ) ‘ The Legión Cívica Argentina and the Radicalisation of Argentine Nacionalismo during the Década Infame ’ . Estudios interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe 13 ( 2 ): 5 – 30 .

Laclau , E . ( 1977 ) Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory: Capitalism, Fascism, Populism . New Left Books : London .

Laclau , E . ( 2005 ) On Populist Reason . Verso : London . Lanusse , L . ( 2005 ) Montoneros: el mito de sus 12 fundadores . Vergara : Buenos Aires . Lastra , B . ( 1944 ) Bajo el signo nacionalista: escritos y discursos . Alianza : Buenos Aires . La Barbarie (1964) Buenos Aires . La Nación (1938 – 1966) Buenos Aires . La Opinión (1973) Buenos Aires . Marchar (1974) Buenos Aires . 18 de Marzo (1962 – 1963) Buenos Aires . McCaughan , M . ( 2001 ) True Crimes: Rodolfo Walsh and the Role of the Intellectual in

Latin American Politics . Latin American Bureau : London . McGee Deutsch , S . ( 1999 ) Las Derechas: The Extreme Right in Argentina, Brazil, and

Chile, 1890 – 1939 . Stanford University Press : Stanford . McGee Deutsch , S. and Dolkart , R . ( eds. ) ( 1993 ) The Argentine Right: Its History

and its Intellectual Origins, 1910 to the Present . Scholarly Resources : Wilmington Militancía (1973) .

Moyano , M. J . ( 1995 ) Argentina ’ s Lost Patrol: Armed Struggle, 1969 – 1979 . Yale University Press : New Haven and London .

Navarro Gerassi , M . ( 1968 ) Los nacionalistas . Jorge Álvarez : Buenos Aires . Oliver , J. P . ( 1973 ) Interview by Luis Alberto Romero, 23 June 1973, Archivo de Historia

Oral, Instituto Torcuato di Tella, Buenos Aires . Padrón , J. M . ( 2006 ) Ni yanquis ni marxistas, nacionalistas! Origen y conformación del

Movimiento Nacionalista Tacuara en Tandil, 1960 – 1963, paper presented at the Jornadas La Política en Buenos Aires Siglo XX, Centro de Estudios de Historia Política, Universidad Nacional de San Martín , Buenos Aires , 22 – 23 June 2006 [WWW document] . URL http://www.unsam.edu.ar/escuelas/politica/centro_historia_politica/material1/ padron.pdf [accessed 12 March 2007] .

© 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 Society for Latin American StudiesBulletin of Latin American Research Vol. 26, No. 3 377

Argentine Nationalism

Pérez , E . ( 2002 ) ‘ Una aproximación a la historia de las FAP ’ , in E. L. Duhalde and E. Pérez ( eds .) De Taco Ralo a la alternativa independiente: historia documental de las Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas y del Peronismo de Base . La Campana : La Plata , 22 – 106 .

Pozzi , P . ( 2004 ) ‘ Por las sendas argentinas ’ : el PRT-ERP, la guerrilla marxista . Imago Mundi : Buenos Aires .

Primera Plana (1962 – 1969) Buenos Aires . Puiggrós , R . ( 1968 ) El proletariado en la revolución nacional . Sudestada : Buenos Aires

[1958] . Quattrocchi-Woisson , D . ( 1992 ) Un nationalisme de déracinés: l ’ Argentine, pays malade de

sa mémoire . CNRS : Paris and Toulouse . Queraltó , J. E. R . ( 1985 ) Interview by Gerardo Bra . Todo es Historia 216 : 68 – 71 . Rein , R . ( 2003 ) Argentina, Israel, and the Jews: Perón, the Eichmann Capture and After .

University of Maryland Press : Bethesda . Rock , D . ( 1991 ) ‘ Argentina, 1930 – 46 ’ , in L. Bethell ( ed .) The Cambridge History of Latin

America , Vol. 8 . Cambridge University Press : Cambridge , 3 – 71 . Rock , D . ( 1993 ) Authoritarian Argentina: The Nationalist Movement, its History and its

Impact . University of California Press : Berkeley . Rot , G . ( 2000 ) Los orígenes perdidos de la guerrilla en la Argentina: la historia de Jorge

Ricardo Masetti y el Ejército Guerrillero del Pueblo . El Cielo por Asalto : Buenos Aires . Rouquié , A . ( 1978 ) Pouvoir militaire et société politique en République Argentine . Fondation

Nationale des Sciences Politiques and CNRS : Paris . Salas , E . ( 2003 ) Uturuncos: el origen de la guerrilla peronista . Biblos : Buenos Aires . Senkman , L . ( 1986 ) El antisemitismo en la Argentina , Vol. 1 . CEAL : Buenos Aires . Seoane , M . ( 2003 ) Todo o nada: la historia secreta y la historia pública del jefe guerrillero

Mario Roberto Santucho . Planeta : Buenos Aires . Seoane , M . ( 2005 ) ‘ Murió Kelly, un provocador político con pasado violento ’ . Clarín ,