Michael Fontenot (€¦ · 3.0 The recognition of customary law p.4 3.1 Advantages p.4 3.2...

Transcript of Michael Fontenot (€¦ · 3.0 The recognition of customary law p.4 3.1 Advantages p.4 3.2...

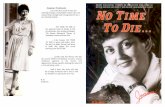

Front cover photo: ‘Aboriginal Dance’, Paronella Park, Mena Creek, Queensland. Photo by Michael Fontenot (http://www.flickr.com/people/trblmkr/) This report was commissioned as part of the 2009 Queensland Parliamentary Internship Program by The Honourable Dean Wells MP. Report author contact: Sam Hussey-Smith 9 Morris St Paddington Brisbane, Queensland 4064 Ph: 0438 11 4323 E: [email protected] With thanks to: Stephen Bell, Uncle Peter Bird, Uncle George Bostock, Fiona Craigie, Aunty Alex Gater, Uncle Albert Holt, Graeme Kinnear, Uncle Joe McDonald, Julia Noble, Magistrate Tina Previtera, Dean Wells

Table of Contents

Executive Summary p.2 Definitions p.2 1.0 Introduction p.3 2.0 Key points of difference between customary and Australian law p.3 3.0 The recognition of customary law p.4

3.1 Advantages p.4 3.2 Disadvantages p.5

4.0 The Murri Courts p.6

4.1 A History of Aboriginal Courts in Australia p.6 4.2 What is the Murri Court? P.7

4.3 Background to the Murri Court p.8 4.4 How the Murri Court works p.8

4.4.1 Elders p.8 4.4.2 Community Justice Groups p.10

4.5 Legislative framework for the Murri Courts p.10 4.6 Murri Court jurisdiction p.11 5.0 Interstate experiences p.11

5.1 South Australia – Nunga Court p.12 5.2 New South Wales – Circle Sentencing p.12

6.0 The incorporation of customary law into Queensland law? p.12 7.0 Conclusion p.13 8.0 Recommendations p.14

8.1 Customary law should be recognised, but not incorporated into Queensland law p.14 8.2 Increased participation by Elders in sentencing process p.14 8.3 Appropriate remuneration for Aboriginal Elders p.14 8.4 The institutionalisation and appropriate resourcing of CJGs and the establishment of a CJG in Brisbane p.15 8.5 Purpose-built Murri Courts p.15 8.6 Legislative recognition of Murri Courts p.15

Reference List p.16 Appendices p.19 Schedule of Interviews p.21

1

Executive Summary The Murri Courts are sentencing courts located throughout Queensland available to Indigenous persons who have pleaded guilty to an offence which can be heard by a Magistrate. The court first sat in 2002 with the aims of reducing the over-representation of Aboriginals in prison, reducing the number of Indigenous offenders who fail to appear in court, and decreasing the reoffending rate of Indigenous offenders. These goals were to be achieved by incorporating principles of Indigenous justice and allowing family members, community justice groups and, most importantly, Aboriginal Elders to play a part in the proceedings. While the Queensland Murri Courts have been credited with reducing recidivism rates and creating a more culturally appropriate court environment for Indigenous persons, concerns have been raised that the Murri Court is seen as lenient or unnecessarily divisive to the community. In considering this, the notion of incorporating some aspects of customary law into Queensland law has been suggested as a way to make sentences more meaningful, and the punishments more culturally appropriate. While this may be appropriate to some extent in very small and remote Indigenous communities, for most areas, the incorporation of customary law is legally impractical and culturally inappropriate. Instead, small but significant changes to the Murri Courts are suggested that grant greater authority to the Elders, secures a place for Community Justice Groups in proceedings, and entrenches in legislation the Courts’ unique place in the legal system. Definitions In this report the terms ‘Indigenous’ and ‘Aboriginal’ are used interchangeably and includes Islanders from the Torres Strait.

2

1.0 Introduction The following report has been commissioned as part of the 2009 Queensland Parliamentary Internship Program. The report seeks to investigate the possibilities of incorporating customary Aboriginal law into the Queensland legal system. More specifically, the report will examine the Queensland Murri Court, and analyse whether elements of customary law are already incorporated into its operations, and whether they can be incorporated any further, if at all. Reference to Indigenous sentencing courts in other Australian jurisdictions will be used to provide context for the Murri Courts’ operations, and used as a basis from which to provide criticisms and recommendations. The historical interplay between black and white law will also be examined, in part to determine exactly what ‘customary law’ is, and to evaluate its compatibility with Australian law. The chequered history of Indigenous, or ‘Native’ Courts, also provides a context from which to evaluate the current constitution of the Murri Courts, and whether they are sufficiently sensitive to the specific needs of Indigenous people. While acknowledging the richness and well-documented existence of Indigenous law prior to British arrival, the diversity of customary law found throughout Queensland, and the increasing urbanisation of Indigenous people, means it has limited application in the Queensland legal system. Ultimately, it will be concluded that customary law is generally incompatible with mainstream Queensland law; however, there is most certainly a place for the enhancement of customary traditions and authority structures within the Murri Courts, along with a need to better adapt court proceedings to better meet the requirements of Indigenous people. At the core of these enhancements is a focus on developing and fostering the authority and input of Elders into the Murri Court process. As the former Chief Magistrate of the Magistrates Court has acknowledged “the key to the success of the Murri Court is the involvement of the elders and respected persons in the proceedings” (Irwin 2008a: 3), and it is hoped the Elders’ essential role will be further enhanced and valued by the findings of this report. 2.0 Key points of difference between customary and Australian law Early attempts to reconcile the two laws by the British were crude and often misunderstood or ignored by Indigenous people (Appendix 1). Firstly, the conception of private ownership of land was completely alien to Indigenous people. A strong spiritual link existed between Aboriginals and their place of birth, or even conception, and was possessed a strong spiritual significance. The land was inalienable, and no individual could exercise control or ownership over it. Indeed, “it would be as correct to speak of the land possessing men as of men possessing land” (Maddock 1975: 27). Women and men practised distinctly different systems of law and, in almost all instances, the processes of judgement, punishment and enforcement were carried out by community members of the same gender as the offender. While there was overlapping law between men and women, it is now recognised that different laws applied to different genders. Importantly, knowledge of these laws was kept exclusively within the gender group; this forms the basis for the contemporary terms ‘women’s business’ and ‘men’s business’. Breaches of sacred law were taken very seriously, and harshly punished. Witnessing sacred objects, places or ceremonies (even unintentionally) was an offence against sacred law (ALRC 1980: 17). Unlawfully possessing this knowledge entitled the rightful holder(s) to immediate retribution, usually in the form of spearing, which could lead to death. Australian law doesn’t recognise the sacredness of Indigenous knowledge and any punishment enacted as a result of it would be considered a crime.

3

As explained above, the question of intention is irrelevant in customary law. For certain offences, punishment can be swift and cruel. In these cases, the aggrieved party is empowered (obliged, even) to ensure that punishment is immediately carried out. The clear distinction between rules of law and rules of polite behaviour or custom as seen in Australian society is much less distinct in Aboriginal society. As Meggitt notes, “the care of sacred objects… the sexual division of labour, the avoidance of mothers-in-law… the rising of the sun, and the use of fire-ploughs are all forms of behaviour that is lawful and proper” (1976: 252). The traditional Indigenous conception of ‘the law’ is one that applies not just to individuals, but also to animals, insects, supernatural beings, flora and the seasonal cycles of the environment. Thus, customary law is far more pervasive and comprehensive than Australian law. The Australian conception of law as something invoked only at the moment it is broken is at odds with the Indigenous conception of law that regulates social norms, sacred knowledge, and even natural processes. Punishment under Australian law tends to be limited to community service, monetary fines, a court order to do or cease from doing something, or incarceration. Indigenous punishments were more varied and certainly – at least by modern Australian standards – much more violent. Meggitt (1976) ranks a series of common customary law punishments that varied according to the seriousness of the offence:

• Ridicule • Oral abuse – this accompanies all other punishments • Battery – attack with a club or boomerang • Wounding – attack with a knife or spear • Illness – caused by sorcery • Insanity – caused by sorcery • Death – caused either by physical attack or sorcery

So while there were no formal institutions of government, or institutionalised law enforcing agencies, sophisticated and pervasive systems for the regulation of law, order and proper behaviour existed among Aboriginals. Nevertheless, the differences between the two laws remains profound (Appendix 2), and accommodating one without diminishing the other presents serious challenges. 3.0 The recognition of customary law 3.1 Advantages The groundbreaking Australian Law Reform Commission (1985) report into the recognition of customary law found that there was broad Aboriginal support for some recognition and a strong desire for customary laws to operate alongside Australian law. The report noted that many Indigenous people believed Australian law to be too weak, and left them unable to manage their affairs through traditional authority and punishment mechanisms (ALRC 1985). In particular, it was argued that Australian law was ill-equipped to deal with alcohol-related problems. The positive liberties (for example, the freedom to drink to excess) and the negative liberties (for example, the freedom from government interference with your drinking habits) so central to the Australian liberal tradition of government have eroded the Indigenous notions of collective and community justice (Berlin 2006: 369). The individualist focus of Australian law is in many ways the opposite of the community-centred Indigenous approach to law. Recognition of customary law would go some way to addressing this problem, and place power for dispensing justice back into the hands of communities.

4

The ‘tyranny of distance’ that characterises Australia also makes effective law enforcement extremely difficult in remote communities, a problem that ostensibly precipitated the federal government’s 2007 intervention into the Northern Territory (Toohey 2008). Empowering local communities to dispense justice appropriate to their community is certainly desirable in some instances. While the law is seen by non-Indigenous Australians as a force for peace and order, many Aboriginals have witnessed first hand the inadequacy of white-man’s law in addressing social breakdown. Kirby notes that this inadequacy gives credibility to the notion that “the recreation of respect for Aboriginal customary laws would give fresh stability to Aboriginal society and protection against the erosion of Aboriginal identity” (1983: 122). The recognition of customary law would foster a unique sense of identity amongst Aboriginal Australians, and legislatively entrench their special place in the nation’s history. Behrendt argues that piecemeal reforms of the dominant legal system are a waste of time and resources. In fact, Behrendt argues, “law reform of the imposed legal system is designed to keep Aboriginal people within the dominant legal system and thus tries to reinforce the legal fiction that Aboriginal people are not a sovereign nation” (1995: 107). Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Australia is signatory, states that:

In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, or to use their own language (OHCHR 1966).

Considering the complex and intertwined relationship between religion, culture and law in Indigenous society, it could be argued that non-acknowledgement of customary law (at least where it conflicts with Australian law) constitutes a breach of Article 27 of the ICCPR. The language of the Article is sufficiently broad so as to include aspects of customary law, and a number of Indigenous leaders agree that the provisions of the ICCPR seek to achieve this end (Calma 2006). Calma (2006) notes that despite the colonisation of Indigenous people and the historical degradation of Aboriginal culture and traditions, 62 per cent of young Aboriginals recognise their traditional country, 47 per cent identify with a clan or tribal group, and 66 per cent attended a cultural event in the last 12 months. This is compelling evidence that Aboriginal culture remains alive and well and that, despite government policies predicated on assimilation and the dilution of culture, Australian Aborigines retain strong ties to their traditional culture and customs. 3.2 Disadvantages While a limited recognition of customary law has been generally welcomed by judges, court officials and Indigenous persons, there are obvious limits to its application. There are no known Aboriginal people now living what could be considered ‘traditional’ lifestyles, at least on a permanent basis. In all Aboriginal communities, particularly in cities and towns, the evidence of white settlement – from physical infrastructure and technology to changes in diet, clothing and language – is pervasive. Of course, as part of this cultural shift, Aboriginal knowledge of the British-derived legal system has substantially increased, and it has become increasingly difficult for Aboriginals to invoke customary law as a defence in criminal trials. Additionally, recognising customary law can resemble a zero-sum game for the Australian legal system, because as customary law advances as a body of recognised law, Australian law has to give way or retreat. Judges and lawyers have often struggled to reconcile the two bodies of law,

5

and not only because they are educated, trained and immersed in British-derived law. In some cases, recognising customary law has resulted in “a kind of weak legal pluralism” (UQ 2009) that can lead to the “informal recognition of customary law as an alternative legal authority under scrutiny by the white legal authority” (UQ 2009). The common law system inherited by Australia from the United Kingdom was intended to be the sole source of law and is poorly designed to incorporate alternative sources of law. Douglas (2005) refers to the incorporation of customary law as a prolonged ‘stretching’ of the Australian legal system that has lessened the authority and purview of both Aboriginal and Australian law. In relation to ‘payback’, whereby Aboriginal tribes mete out their own punishments to the guilty party (NTLRC 2003), “judges both take into account the proposed punishments and yet do not formally condone it” (Douglas 2005: 141). If a judge is to take account of tribal retribution during sentencing, they are essentially co-opting an Aboriginal community into the process of sentencing and punishment. This raises serious questions about judicial accountability. Firstly, the unique authority of the judiciary is potentially compromised by “being beholden to Aboriginal communities for evidence of appropriate customary responses” (Douglas 2005: 141). Unlike Australia’s documented legal system (codified in either legislation or judicial precedents) customary law is neither documented nor consistent across Australia (ALRC 1980). Secondly, Douglas notes, recognition of traditional law and punishments lead to the situation where “Aboriginal people are both supervised and supervisor, and the state is both in, and out of, control” (2005: 141). While ceding some government responsibilities to non-state actors does not necessarily mean that states are in decline or ‘out of control’ (Bell and Hindmoor 2009), it could certainly encourage that view among both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous community. There is also a risk that forcing judges to recognise customary law could allow some offenders to disingenuously invoke customary law principles to lessen their punishment for a serious crime. Indeed, it was just such a fear that prompted former Attorney-General Philip Ruddock to pass the Crimes Amendment (Bail and Sentencing) Act in 2006 that specifically removed the requirement for federal judges to consider ‘cultural background’ during sentencing or bail applications (Law Council of Australia 2006). 4.0 The Murri Courts 4.1 A History of Aboriginal Courts in Australia Although Indigenous sentencing courts in their current form are a relatively recent innovation, courts ostensibly tailored to the needs of Indigenous persons have existed in Australia since the 1930s. While most early Aboriginal courts were highly informal, the West Australian government sought to entrench ‘Courts of Native Affairs’ through the passing of the Native Administration Act 1936. The courts were established following several inter-clan massacres in Western Australia and the apparent inability of the legal system to adequately punish, or even properly identify, the protagonists (Auty 2000: 150). While the push to establish Native Courts was led by a number of well-intentioned and high-profile figures eager to see expanded autonomy for Aboriginal people, the Courts were ultimately “used as a vehicle of colonial control” (Harris 2004: 27). The Native Courts abolished the common law right to a trial by jury, elevated to powerful positions men without traditional authority (but with a grasp of English), and outlawed appeals to higher courts (Auty 2000: 152). In Queensland, special courts permitted to hear offences committed by Aboriginal people who lived on reserves were established by the Aboriginal Preservation and Protection Act (Qld) 1939.

6

The Act did not seek to empower Indigenous people to deal with their own disputes; rather, extensive powers were granted to the Chief Protector of Aborigines, and these powers were devolved to local superintendents on the reserves. The superintendents, typically white missionaries, would establish Aboriginal courts to deal with a range of offences (ALRC 1986: 26). Although the courts established on the reserves were constituted ostensibly to serve the interests of the local Aboriginals, the reality was the courts were used to assert authoritarian control over and to more intimately manage their day-to-day lives. As Cunneen notes “there were many ‘offences’ which were specific to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, not defined as criminal in the broader community” (2001: 74). From 1965, Aboriginal Justices of the Peace were empowered to preside over Aboriginal Courts on reserves. However, there were several criticisms of these courts, notably that they often subverted traditional authority structures, had an inability to take into account local customs and traditions, and were generally inferior or ‘second-class’ institutions (ALRC 1986: 34). The Community Services Act (Aborigines) Act passed in 1984 allowed for the establishment of Aboriginal Courts to be adjudicated by two Aboriginal Justices of the Peace. While termed ‘Aboriginal Courts’, they were very limited in scope and effectively involved “the enforcement by Aboriginal personnel of a set of local by-laws” (ALRC 1986: 26). Again, this court system failed to utilise traditional authority structures and represented “another ‘solution’ which communities neither wanted nor found relevant” (O’Donnell 1995: 89). In 1991, the Queensland Attorney-General Dean Wells launched the Community Justice Programme (CJP) to provide mediation services that were premised on a recognition that “traditional Western processes of dispute resolution are no longer always appropriate… in Aboriginal communities” (O’Donnell 1995: 90). While open to all Queenslanders, there was a strong focus on engaging with and empowering Aboriginal communities, through mediators (a number of whom were Indigenous) to achieve outcomes acceptable to all parties. One aspect of the CJP was the Crime Reparation Programme, which encouraged offenders and victims to reach mutually acceptable outcomes through mediators, and established the framework for future court innovations. 4.2 What is the Murri Court? The Queensland Murri Courts are a series of Magistrates Courts specifically constituted to sentence Indigenous offenders who plead guilty to minor criminal (summary) offences which fall within the jurisdiction of the Magistrates Court (Westcott 2006: 1). First sitting in August 2002, the Court represented an opportunity to make the court process less intimidating for Aboriginals, and allowed the Magistrate to hand out more culturally appropriate sentences. Indigenous Elders are present in the Murri Court and sit alongside the Magistrate at eye-level with the offender, their lawyer, and the prosecution. There is at least one Elder and up to four present in any one sitting day. While it is still the Magistrate who presides over the Murri Court, and ultimately sentences the offender, the Magistrate is encouraged to discuss with Elders the most appropriate and meaningful sentence. Community Justice Groups (CJGs), family and supporters are all encouraged to attend, with the Magistrate or Elders often deferring to one or all of these parties for input on the sentencing. To be sentenced in the Murri Court, the offender must identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, and both the prosecution and offender must consent to the matter being dealt with in the Murri Court (DJAG 2006a: 1). Murri Courts are characterised by their informality. Magistrates do not wear robes or wigs and police prosecutors do not wear uniforms; the defendant can sit with a support person (such as a family member) who can speak for them, as well as a lawyer; and all parties sit around a conference table at eye-level (Westcott 2006: 1-2).

7

Murri Courts operate in Brisbane, Caboolture, Cleveland, Ipswich, Cherbourg, Mount Isa, Rockhampton and Townsville (DJAG 2009). 4.3 Background to the Murri Court The shocking over-representation of Aboriginal persons in Australia’s prisons revealed in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody encouraged all levels of government to commit to reducing Indigenous disadvantage and developing programs that diverted Aboriginals from prison. While initiatives in the areas of Indigenous health, education and employment were enacted shortly after the Inquiry was released, it wasn’t until 1999 that major changes to sentencing processes were first trialled in Australia, in the form of South Australia’s Nunga Court (Irwin 2008b: 3). In Queensland, in December 2000, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement was signed by the Queensland government and the members of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Board with a central goal of reducing the rate of Indigenous incarceration by 50 per cent by 2011 (Irwin 2008b: 3; Cunneen, Collings and Ralph 2005). A key aspect of this new justice strategy was to build “a more culturally sensitive criminal justice system” (ATNS 2003), and it was on this basis that the Queensland’s Murri Courts were established in 2002. Like Indigenous courts in other jurisdictions, the effort to implement an Indigenous sentencing court in Queensland was spearheaded by Magistrates and community members eager to reverse the gross over-representation of Aboriginals in the prison system. Indigenous persons in Queensland constitute approximately 3.5 per cent of the population, but represent nearly 27 per cent of the adult prison population, and 60 per cent of the juvenile prison population (DJAG 2006b: 2). This over-representation means Indigenous youths were approximately 25 times more likely to be in detention than non-Indigenous youths (Australian Institute of Criminology 2009: 30). The Queensland government wanted to try a new approach to sentencing, one that incorporated culturally appropriate practices such as Elders, a more informal courtroom arrangement, and the diversion of Indigenous offenders from prison to community-based and monitored rehabilitation programs. On establishment, the Murri Court set out to achieve three key objectives:

(i) To help redress the over-representation of Indigenous offenders who pass through the criminal justice system and who end up in prison;

(ii) To reduce the number of Indigenous offenders who fail to appear in court, which can lead to the issue of warrants for arrest and imprisonment; and

(iii) To decrease the reoffending rate of Murri offenders and the number of court orders which are breached, which can also lead to prison

(Parker and Pathé 2006: 23) 4.4 How the Murri Court works 4.4.1 Elders As former Chief Magistrate Marshall Irwin stated at last year’s Murri Court conference, “the key to the success of the Murri Court is the involvement of the elders and respected persons in the proceedings” (2008a: 3).

8

Murri Court Elders assist the Magistrate during proceedings in a number of important way, including:

• Advising the Magistrate on cultural issues; • Providing background information about the offender; • Explaining the meaning of the Magistrate’s questions or concerns to the offender; • Acting as a liaison with local Indigenous communities; and • Providing advice to the Magistrate on the appropriateness of proposed court orders and

conditions (Westcott 2006: 2).

In addition to these formal roles, Elders often directly address the offender shortly before sentencing. During this time, the Elders generally admonish the defendant and invoke their traditional authority as an Elder. This shaming by an Elder has its basis in customary law (the custom of ridicule) and has the effect of making any sentence much more meaningful to the offender and the community (Parker and Pathé 2006: 23). During sentencing, a number of Elders make reference to Christian notions of moral behaviour, humility and justice, and encourage the offender to attend church, or at least try to conduct themselves according to Christian principles. The Elders enable and legitimise the Murri Court, and are essential to its operations. Irwin (2008a) notes that the presence of the Elders provides the court with a much greater level of information on the defendants’ circumstances than would have been available otherwise, assists the defendant in understanding the court processes and the consequences of their actions, and improves Indigenous people’s perceptions of the courts’ and Magistrates’ authority. For their efforts, which often involve committing a whole day to the proceedings, Murri Court Elders can claim up to $36.50 per day in expenses such as transport, or lunch (DJAG 2006b: 5). This is despite the fact that Murri Court elders carry on a number of highly important tasks outside the Murri Court that are essential to its operations. As Queensland Magistrate Stephanie Tonkin notes, “the Elders are mostly elderly persons who have significant family responsibilities to grandchildren, and often have their own health problems… the work is time-consuming and emotionally draining” (2009: 5). Elders are also expected to attend basic legal and court training sessions. While Elders may not appear to have a great deal of input during the actual sentencing hearing (aside from the public shaming of the offender), “the main interaction between the Elders and an offender usually occurs at pre-hearing meetings” (Marchetti 2009: 3). This is an extensive consultation where the Elders discuss the hearing with the offender, and talk to family and supporters about appropriate punishments. In this sense, the Elders are de facto officers of the court, carrying out a significant amount of ‘leg work’ to achieve the best outcome for the community and the offender. Many Elders also volunteer to visit offenders in prison, and check-up on offenders participating in community-based orders. While there are few complaints from Elders about their lack of compensation, there are suggestions that much of this has to do with an ingrained belief on the part of Elders in government dishonesty and discrimination. Many of the Murri Court Elders lived in Queensland under the Aboriginal Protection Act, which quarantined Indigenous wages until 1972, and encouraged discriminatory pay scales until the late 1980s (ANTAR 2003). In Victoria’s Koori Court, Elders are paid a sitting fee of $150 per day, although in most other jurisdictions Elders are not paid for their services (Harris 2006: 45).

9

4.4.2 Community Justice Groups Community Justice Groups (CJGs) were set up in Queensland in 1993 following the release of the findings of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody that raised concerns about the ability of Indigenous people to access adequate legal representation. In Queensland there are 41 registered CJGs tasked with supporting Indigenous victims and offenders at all stages of the legal process, encouraging and coordinating diversionary punishments, and developing networks with other agencies to ensure that Indigenous people have access to legal representation (DJAG 2009b). The majority of CJG members, aside from a single paid coordinator, are volunteers, including Elders and respected persons, traditional owners and community members of ‘good standing’ (DJAG 2008: 2). The legislation1 governing CJGs also encourages them to play a coordinating role in organising Elders, making sure defendants arrive for their hearing and preparing them for their sentence, and liaising with the Magistrate and Elders as to which punishment might be appropriate, and suggesting possible diversionary programs (DJAG 2009b). CJGs also work with offenders post-sentence on community-based orders and visit Aboriginals in prison (Tonkin 2009: 5). CJGs operate throughout Queensland and receive funding from the state government but, like the elders, the “Murri Courts rely heavily on CJGs for their functioning” (Tonkin 2009: 5). Despite providing a major contribution to the Murri Courts’ goals the CJGs remain under-resourced and undervalued. The ability of the Murri Court to effect real change and tackle recidivism is dependent on the diversionary programs that take place outside of the court’s purview, but within that of the CJGs. Without the CJGs, Magistrates are limited in the variety of punishments that can be handed down, and too often only left with imprisonment as a punishment. This is particularly relevant in Brisbane, which lacks a CJG because of its large size, the competing claims of traditional owners and the number of overlapping clans that live within the city. Tonkin argues that without adequately funded diversionary programs and CJGs “many offenders will not be able to bring about the significant changes in their lives necessary both to prevent their reoffending and the endless cycle of incarceration” (2009: 7) 4.5 Legislative framework for the Murri Courts Blagg points out that few Indigenous sentencing courts are entrenched in legislation, and that “arrangements have tended to be relatively ad hoc and dependent upon the energies and commitment of local magistrates, prosecutory authorities and senior members of the Indigenous community” (2008 :127). The Murri Court is no different, and the legislative framework for its existence is fairly weak. Three Acts govern the operations of the Murri Courts.2 No mention of the Murri Courts are made in these Acts; rather, all the Acts state is that in bail and sentencing procedures for Indigenous offenders, courts must take into account the community and cultural background of the offender, and any rehabilitative programs or services that CJGs advise might be appropriate. Elders are included in the definition of CJGs and their role is not prescribed. The vague nature of the legislation is one of the reasons Murri Courts vary so much in their operations across the state. While this could be construed as an encouragement to develop locally appropriate Indigenous courts, it also leaves the legal basis of the Murri Courts uncertain. Funding for Murri Court coordinators and regional staff is non-recurrent and will be reviewed at the end of 2009.

1 Penalties and Sentences Act 1992, Juvenile Justice Act 1992 and the Bail Act 1980. 2 Ibid.

10

4.6 An expanded jurisdiction for Murri Courts? Serious crimes such as assault, manslaughter or armed robbery cannot be dealt with by the Murri Courts, and this is perhaps appropriate; the more severe punishments traditionally handed down for such crimes are often violent and in conflict with Australia’s human rights obligations. Other matters, such as civil disputes, could be accommodated within the Murri Courts’ jurisdiction. Disputes between individuals are common in customary law settings, and discrete Aboriginal dispute resolution mechanisms have existed to deal with them for thousands of years. Presently the Murri Courts are accessible to only a very small minority of individuals who come into contact with the Queensland legal system. The Murri Courts are constituted specifically to sentence Indigenous offenders who have pleaded guilty to a summary offence which falls within the jurisdiction of the Queensland Magistrates Court. While the existence of the Murri Courts is an important acknowledgement that traditional authority structures can positively contribute to the Queensland justice system, it is also a rather narrow interpretation of how traditional law can assist with the administration of justice. When resolving disputes between individuals in traditional Indigenous communities, the focus was not on restitution for the wronged person, but on engaging all parties in a consensus-based process designed to restore community harmony as quickly as possible (ALRC 1980: 2). While an independent umpire traditionally was not a part of this process, Elders were often engaged to guide the process and provide input. Because disputes had the potential to adversely affect the entire community “every member was likely to become involved in the resolution of the dispute” (ALRC 1980: 2). Indeed, if there were a guiding principle to dispute resolution in Indigenous settings, it would be to “restore peace and good relations – sometimes regardless of who is right and wrong – and sometimes even regardless of fairness in the Western sense” (Clifford 1977: 6). The Murri Court structure is flexible enough for it to deal with a number of legal issues and disputes, and not just the sentencing of offenders. Inter-clan disputes, which are a particular problem in larger urban areas with overlapping tribal land claims, could be resolved through the Murri Courts. Individual, inter- or intra-family disputes could also be heard in the Murri Courts, incorporating the traditional authority of Elders and the opinions and concerns of affected community members. Widening the jurisdiction of the Murri Courts to include civil claims and other matters could also reduce the negative perceptions of the justice system held by many Aborigines, as they come to see the Australian legal system as a means for peace, order and social cohesiveness, rather than simply as a mechanism for punishment (Kirby 1983: 122). 5.0 Interstate experiences The Murri Courts in Queensland are by no means unique. All Australian jurisdictions, with the exception of Tasmania, now operate courts that incorporate Indigenous Elders and/or principles of Indigenous justice into the sentencing process (Fitzgerald 2008: 1). Indigenous people around Australia are served by the Koori Court in Victoria, the Community Courts in the Northern Territory, the Ngambra Circle Court in the Australian Capital Territory, the Nunga Court in South Australia, the Kalgoorlie-Boulder Community Court in Western Australia and Circle Sentencing in New South Wales (Westcott 2006: 1; DOTAG 2007: 1; NTDJ 2005). Like Queensland’s Murri Courts, the names of the interstate courts generally utilise the Aboriginal term for the region in which the court is located, or the traditional method used to dispense justice (Harris 2004).

11

5.1 South Australia – Nunga Court The Nunga Court in South Australia was the first urban Aboriginal sentencing court to commence operations when it was established in June 1999. The court was the initiative of Magistrate Chris Vass, the regional manager of the Port Adelaide Magistrates Court and its associated circuits. After 17 years working on the Magistrates circuit that took in a number of Indigenous communities, Vass found that “Aboriginal people mistrusted the justice system, including the courts [and] felt they had limited input into the judicial process generally and sentencing deliberations specifically” (Tomaino 2004: 2). The Nunga Courts aimed to provide a more culturally appropriate setting than mainstream courts, break the cycle of recidivism and to improve the court participation rates of Aboriginal people (Tomaino 2004: 3-4). The setting is much more informal than a mainstream court, Elders play an important part in the sentencing, and all parties sit at eye-level around a table. A study released on the five-year anniversary of the Nunga Court found that participation rates averaged between 80-95 per cent, compared with around 50 per cent in mainstream courts (Tomaino 2004: 4). The improved attendance rates fostered a greater understanding by Aboriginal people of court processes, and led to a reduction in the number of warrants issued, which in turn has significantly reduced the number of Indigenous persons held in custody in South Australia (Tomaino 2004: 8). 5.2 New South Wales – Circle Sentencing Circle Sentencing was introduced to the New South Wales town of Nowra in 2002 with four aims: to empower Aboriginal communities in the sentencing process by reducing barriers that exist between courts and Aboriginal people; to provide more meaningful and realistic sentences to Aboriginal offenders; to improve the support provided to victims of crime and to encourage reconciliation between aggrieved parties; and to break the cycle of recidivism for Indigenous offenders (Potas et al. 2003: 1). Circle Sentencing is a much more informal environment than the Murri Courts. As the name suggests, all participants including the Magistrate, Elders, supporters and the offender sit in a circle and openly discuss the relevant factors to be considered. Magistrates do not wear robes or wigs, and typically also remove coats and ties. As Dick and Wallace note, to some Indigenous people – and particularly those unfamiliar with court processes – desks, coats, ties, wigs and robes can symbolise “the trappings and formalities of western institutions that have always signified for Aboriginal people their powerlessness and the power of ‘white man’ over them” (2007: 5). Derived from the Canadian model of circle sentencing developed in 1992 to work with First Canadians, the focus on Circle Sentencing in New South Wales is on power sharing between the Magistrate, the Elders and the local community. While an independent review of Circle Sentencing found it had achieved success in some areas, particularly in making the sentencing experience more appropriate and meaningful for Indigenous participants (Potas et al. 2003: 51), a more recent study concluded that Circle Sentencing had no long-term impact on rates of recidivism (Fitzgerald 2008: 1). The New South Wales government has since committed to making Circle Sentencing ‘more formal’ and to strengthening drug and alcohol treatment programs (ABC 2008). 6.0 The incorporation of customary law into Queensland law? The basis on which Murri Courts were founded was one in which Australian law would be used, but the environment in which the law operated would be adjusted enough to make the setting, the sentencing and the overall process more culturally appropriate for Aboriginals.

12

As Marchetti and Daly note, Aboriginal sentencing courts “are not practising or adopting Indigenous customary laws… rather, they are using Australian criminal laws and procedures when sentencing Indigenous people, while allowing Indigenous Elders or Respected Persons to participate in the process” (2007: 420). Indeed, the Murri Courts’ own publications are at pains to suggest that they are not a “soft option” (DJAG 2006: 2) and that the Magistrate has complete control over the courts’ operations. The earlier discussion of customary Indigenous law puts paid to the claim that Indigenous law – which traditionally included punishments such as lifetime banishment and spearing – is necessarily ‘soft’. A reasonable understanding of customary law would quickly lead to the conclusion that Aboriginal punishments can be very cruel and not conducive to rehabilitation. Internationally recognised principles against the use of physical punishments that could be construed as a form of torture necessarily outlaw a number of punishments central to the enforcement of customary law. The punishments of battery, wounding, illness, insanity and death (Meggitt 1976) are all regarded as unacceptable according to Australian law, and indeed to most Indigenous people. Thus, the ruling out of these key aspects of traditional justice significantly lessens any chance of meaningfully and comprehensively integrating customary law into the Australian legal system. Incorporating customary law also raises the risk of judges inflicting ‘double jeopardy’ on offenders, whereby a punishment is handed down through Australian law but also as part of Aboriginal custom (Kirby 1983: 123). The conclusion from these points could be that when it comes to incorporating customary law, it’s ‘all or nothing’. However, this need not be the case. While noting the unacceptability in Australian law of the most severe customary punishments such as spearing, other punishments and principles of traditional law could be meaningfully integrated into the Australian system. Indeed, the traditional punishment of ‘ridicule’ is already practised in the Murri Court via the public shaming of the offender in front of the Elders and their community. Additionally, the Murri Court practice that utilises the traditional authority of Elders and the encouragement of community input into proceedings are principles of Indigenous justice that have been practised in Australia for thousands of years. The aspects of customary law that have already been integrated into the Murri Courts’ operations should be enhanced and built upon. The respect reserved for Elders is fundamental to the principles of Indigenous law and their authority in the community should be further recognised in the Murri Courts. This will have the effect of perpetuating the role of Indigenous Elders and go some way to restoring the traditional authority structures largely destroyed following British settlement. 7.0 Conclusion The advantage of a comprehensive, codified and established legal system such as Australia’s is that it provides a predictable framework through which a society can be organised. But as Justice Brennan remarked in his 1992 Mabo judgement, “it is imperative in today’s world that the common law should neither be nor be seen to be frozen in an age of racial discrimination”. While the stability and predictability of Australia’s common law legal system is generally seen as an advantage, its inherent tendency to incremental reform can stifle or preclude much-needed change. The maintenance of the well-known “legal fiction” (Faine 1993: i) of terra nullius for over 200 years is a case in point. While full incorporation of customary law into the Australian legal system would be an impossibility, many of the fundamental principles of Indigenous law are already incorporated successfully and there is scope for further integration.

13

A major review of the Murri Court in 2006 found that it was broadly achieving its three stated aims of reducing the over-representation of Aboriginals in prison, rates of recidivism and rates of failure to appear in court (Parker and Pathé 2006). But one of the most profound successes of the Murri Court lies in its ability to legitimise the justice system in the eyes of Aboriginals. The contribution of Elders in the Murri Court lies at the core of its success, and their participation should be maximised and enhanced. Not only will this align with the historical notion of an Elders Council of decision-makers – a tradition that dates back thousands of years – but it will add to the legitimacy of the court, encourage ownership of the process by the Indigenous community, and contribute to the three key goals of the Murri Court in the long-term. 8.0 Recommendations

8.1 Customary law should be recognised, but not incorporated into Queensland law

While acknowledging the long and rich history of Indigenous law in Australia, the problems of incorporating it into Queensland’s system remain too great. The unacceptability of key punishments significantly dilutes traditional law and means that it could never be wholly embraced by the mainstream legal system. However, the principles of Indigenous justice – community endorsed punishments, a Council of Elders and the shaming of offenders – should and must continue to be incorporated into Queensland law and the operations of the Murri Courts. This will serve to both increase ownership of the justice system by Indigenous people and legitimise its outcomes for offenders.

8.2 Increased participation by Elders in sentencing process

The level of respect for and receptiveness towards Elders by the Indigenous participants in the Murri Court is obvious. In many cases, it is clear that offenders attach more weight to the comments of Elders than the sentencing Magistrate. For this reason, it is recommended that Elders, in consultation with the Magistrate, play a greater role in the sentencing process. It is suggested that this input by Elders into sentencing occur in full view of the offender, their family and their supporters. This would add legitimacy to the sentence in the eyes of the offender and their community and would more closely resemble the consensus-focused sentencing that occurs in New South Wales’s Circle Sentencing.

8.3 Appropriate remuneration for Aboriginal Elders Many Murri Court Elders already have significant commitments to their community, suffer from health problems associated with old age, and live in areas poorly serviced by public transport. Despite this, Elders feel a strong enough sense of community responsibility and therefore give up a day each week to participate in the Murri Courts. Many of the Murri Courts’ Elders also feel very strong kin and clan obligations to the Murri Courts, and thus would participate whether they were reimbursed for their time or not. However, the failure to adequately compensate Elders for their contribution to the Murri Court ignores the essential role they play in the running of the court. In the Murri Court setting, the Elders are as important – if not more so, at least in the eyes of many Indigenous offenders – as the Magistrate. Indeed, the Murri Courts would not exist without the Elders. Court officials have suggested that the majority of Elders aren’t agitating for change in this area on account of Queensland’s history of ‘stolen wages’, and the fact that most of them have lived under conditions in which their pay

14

was quarantined by the state. This history, it is suggested, has fostered a belief by many older Indigenous people that governments are pernicious, discriminatory and prone to theft. Thus, the Murri Court relies to an extent on this historical mistreatment of Aboriginals to keep its costs down. The Koori Court in Victoria remunerates Elders for their participation in the judicial process, and there is no reason the same cannot occur in Queensland. 8.4 The institutionalisation and appropriate resourcing of CJGs and the establishment of a CJG in Brisbane Most CJGs are made up of a team of volunteers and a single paid coordinator. Often CJGs are the coordinators of rehabilitation programs and play an essential role in advising Magistrates and Elders of alternative sentencing options. However, they are overstretched. More and recurrent funding for CJGs would encourage the professionalisation of their organisations, and lead to more opportunities for diversionary and rehabilitative sentences. CJGs often supervise community-based orders, and this essential role should be acknowledged in their funding. The establishment of a pan-tribal Brisbane CJG would also encourage greater access to and knowledge of rehabilitative services and alternative sentencing arrangements in the city, where many of these services are located but not widely known about. 8.5 Purpose-built Murri Courts Where available, Indigenous sentencing courts should be located in geographically distinct areas, away from the mainstream courts. Many Aboriginal persons find the conventional courtrooms intimidating, alienating and associated with persecution rather than justice. In some remote areas of Queensland, Aboriginal sentencing courts are located inside police stations, thus conflating the court system with the police. The historically poor relations between the police service and Indigenous people are a key reason for encouraging efforts to create a distinct separation between the two arms of the state. Until Aboriginals feel comfortable in mainstream court settings and on an equal footing with the authorities, provision should be made for purpose-built or specifically designated Murri Court facilities. 8.6 Legislative recognition of Murri Courts The legislative basis for the Murri Courts is weak and prone to amendment at the whim of the government. At present, the Murri Courts’ existence relies on the dedication of volunteer Elders, CJGs, and Magistrates eager to improve relations between the justice system and the Aboriginal community. The enshrining of Murri Courts in legislation would entrench their operations and provide a firmer basis on which their services to the Aboriginal community could be built upon and improved. The Koori Court in Victoria is grounded in just such legislation and it is widely regarded as the most successful of Australia’s Indigenous sentencing courts. To entrench the Murri Courts in the same way would provide certainty to its operations and an acknowledgement that Indigenous justice is unique and a priority for the Queensland government.

15

Reference List ABC. 2008. Circle sentencing has no effect: study. Accessed 15 October, 2009. Available at http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2008/07/16/2305266.htm ALRC (Australian Law Reform Commission). 1980. Aboriginal Customary Law – Recognition? (Discussion Paper). Sydney: Australian Law Reform Commission. ALRC (Australian Law Reform Commission). 1985. The Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws: Volume 1. Canberra: AGPS. ALRC (Australian Law Reform Commission). 1986. Report into the Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws, Volume 2. Canberra: AGPS. ANTAR (Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation). 2003. Stolen Wages Facts. Accessed 22 October 2009. Available at http://antarqld.org.au/05_involved/facts.html ATNS (Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements Project). 2003. Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Justice Agreement. Accessed 20 October, 2009. Available at http://www.atns.net.au/agreement.asp?EntityID=1048 Australian Institute of Criminology. 2009. Juveniles in Detention in Australia, 1981-2007. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Auty, Kate. 2000. ‘Western Australian Courts on Native Affairs 1936-1954: One of ‘Our’ Little Secrets in the Administration of ‘Justice’ for Aboriginal People’. University of New South Wales Law Journal 23(1): 148-72. Behrendt, Larissa. 1995. Aboriginal Dispute Resolution. Sydney: Federation Press. Bell, Stephen and Andrew Hindmoor. 2009. Rethinking Governance: The Centrality of the State in Modern Society. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. Berlin, Isaiah. 2006. ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’. In Contemporary Political Philosophy: An Anthology, eds. R. Goodin and P. Pettit. Malden, MA: Blackwell. Blagg, Harry. 2008. Crime, Aboriginality and the Decolonisation of Justice. Sydney: Hawkins Press. Calma, Tom. 2006. The integration of Customary Law into the Australian legal system. Speech delivered to the Globalisation, Law and Justice Seminar, University of Western Australia, Perth. Clifford, William. 1977. ‘Aborigines and the Law’. In Aborigines and the Law – Australian Institute of Criminology. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. Cunneen, Chris. 2001. Conflict, Politics and Crime: Aboriginal Communities and the Police. Crows Nest, Sydney: Allen & Unwin. Cunneen, Chris, Neva Collings and Nina Ralph. 2005. Evaluation of the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Agreement. Sydney: University of Sydney Law School Institute of Criminology.

16

Dick, Douglas and Gail Wallace. 2007. Circle Sentencing in New South Wales: Sentencing of Aboriginal Offenders. Address to the AIJA Indigenous Courts Conference, 4-7 September, Mildura, Victoria. DJAG (Department of Justice and Attorney-General, Queensland). 2006a. Queensland’s courts system – The Murri Court. Brisbane: Queensland Government. DJAG (Department of Justice and Attorney-General, Queensland). 2006b. Summary of the Review of the Murri Court. Brisbane: Queensland Government. DJAG (Department of Justice and Attorney-General, Queensland). 2008. Community Justice Groups. Brisbane: Queensland Government. DJAG (Department of Justice and Attorney-General, Queensland). 2009a. Murri Court: Queensland Courts. Accessed 14 October, 2009. Available at http://www.courts.qld.gov.au/1694.htm DJAG (Department of Justice and Attorney-General, Queensland). 2009b. Community Justice Groups – Department of Justice and Attorney-General. Accessed October 25, 2009. Available at http://www.justice.qld.gov.au/669.htm DOTAG (Department of the Attorney General, Western Australia). 2007. Kalgoorlie-Boulder Community Court. Perth: Government of Western Australia. Douglas, Heather. 2005. ‘Customary Law, Sentencing and the Limits of the State’. Canadian Journal of Law and Society 20(1): 141-56. Faine, Jon. 1993. Lawyers in the Alice: Aboriginals and Whitefellas’ Law. Sydney: Federation Press. Fitzgerald, Jacqueline. 2008. Crime and Justice Bulletin, Number 115: Does circle sentencing reduce Aboriginal offending? Sydney: New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. Harris, Mark. 2004. ‘From Australian Courts to Aboriginal Courts in Australia: Bridging the Gap?’. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 16(1): 26-41. Harris, Mark. 2006. A Sentencing Conversation: Evaluation of the Koori Courts Pilot Program, October 2002 – October 2004. Melbourne: Victorian Department of Justice. Irwin, Marhsall. 2008a. ‘Welcome Address’. Speech delivered at the 2008 Murri Court Conference, 22 May, Brisbane. Irwin, Marshall. 2008b. Queensland Murri Court. Speech delivered at the 2008 Law Asia Conference, 31 October, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Kirby, Michael. 1983. Reform the Law: Essays on the Renewal of the Australian Legal System. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. Law Council of Australia. 2006. Recognition of Cultural Factors in Sentencing. Submission to the Council of Australian Governments conference, Canberra. Maddock, Kenneth. 1975. The Australian Aborigines. Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books Australia.

17

Marchetti, Elena and Kathleen Daly. 2007. ‘Indigenous Sentencing Court: Towards a Theoretical and Jurisprudential Model’. Sydney Law Review 29: 415-33. Marchetti, Elena. 2009. Sentencing Indigenous Offenders of Partner Violence. Paper presented at the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration Indigenous Sentencing Courts Conference, Rockhampton. Meggitt, Mervyn. 1976. Desert People. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. NTDJ (Northern Territory Department of Justice). 2005. About the Northern Territory Magistrates Court. Accessed 22 October 2009. Available at http://www.nt.gov.au/justice/ntmc/about.shtml NTLRC (Northern Territory Law Reform Committee). 2003. Aboriginal Communities and Aboriginal Law in the Northern Territory: Background Paper 1. Darwin: NTLRC. O’Donnell, Marg. 1995. ‘Mediation Within Aboriginal Communities: Issues and Challenges’. In Popular Justice and Community Regeneration: Pathways of Indigenous Reform, ed. K. Hazelhurst. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. OHCHR (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights). 1966. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Accessed 29 October, 2009. Available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm Parker, Natalie and Mark Pathé. 2006. Report on the Review of the Murri Court. Brisbane: The Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney General. Potas, Ivan, Jane Smart, Georgia Brignell, Brendan Thomas and Rowena Lawrie. 2003. Circle Sentencing in New South Wales: A Review and Evaluation. Sydney: Judicial Commission of New South Wales. Tomaino, John. Information Bulletin #39: Aboriginal Nunga Courts. Adelaide: South Australian Office of Crime Statistics and Research. Tonkin, Stephanie. 2009. A Justice Revolution: Two Therapeutic Courts in Townsville, Drug Court and Murri Court. Paper presented at the Legal Studies Student Conference, James Cook University, Townsville. Toohey, Paul. 2009. ‘Life and death of a crisis’. The Australian 7 June: 21. UQ (University of Queensland). 2009. Customary Law – Justice Martin Kriewaldt, The University of Queensland. Accessed 2 October 2009. Available at http://www.law.uq.edu.au/jmk-customary-law Westcott, Mary. 2006. Murri Courts – Queensland Parliamentary Research Brief No. 2006/14. Brisbane: Queensland Parliamentary Library.

18

Appendices

Appendix 1 Source: Aboriginal Customary Law – Recognition? (Discussion Paper), Australian Law Reform Commission, 1980. Sydney: Australian Law Reform Commission.

19

Appendix 2

Source: Aboriginal Dispute Resolution, Larissa Behrendt, 1995. Sydney: Federation Press

20

21

Schedule of Interviews

Interviewee Position/Organisation Time/Date Location

Uncle Peter Bird Indigenous Elder – Northern Brisbane Region (Redcliffe)

10am-11am 26 August, 2009

19 Stratford St, Kippa-Ring, QLD, 4021

Fiona Craigie Regional Murri Court Case Coordinator – Department of Justice and Attorney-General

12pm-1pm 30 September, 2009

Queensland Magistrates Court, 363 George St, QLD, 4001

Tina Previtera Magistrate – Queensland Magistrates Court

1pm-2pm 30 September, 2009

Queensland Magistrates Court, 363 George St, QLD, 4001

Aunty Alex Gater Indigenous Elder – Anglican Church and Aboriginal Women for Change

1pm-2pm 30 September, 2009

Queensland Magistrates Court, 363 George St, QLD, 4001

Fiona Craigie Regional Murri Court Case Coordinator – Department of Justice and Attorney-General

10am-11am 27 October, 2009

Via phone

Uncle Peter Bird Indigenous Elder – Northern Brisbane Region (Redcliffe)

10am-11am 24 September, 2009

19 Stratford St, Kippa-Ring, QLD, 4021