RFP Nacimiento Rio Bogota DPN Res 142 de 1982 (Acuerdo 10 del 82)

Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

-

Upload

charleigh29calma -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

0

Transcript of Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

-

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

1/22

-

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

2/22

Medical Care Research and Review

69(1) 6282

The Author(s) 2012Reprints and permission: http://www.

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1077558711409946

http://mcr.sagepub.com

409946MCR69110.1177/1077558711409946Meyeroefer et al.Medical CareResearch and Review

This article, submitted toMedical Care Research and Reviewon May 14, 2009, was revised and accepted

for publication on April 11, 2011.

1Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA

2Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., Washington, DC, USA

Corresponding Author:

Chad D. Meyerhoefer, Lehigh University, Rauch Business Center, Rm 459, 621 Taylor Street, Bethlehem,

PA 18015-3117, USA

Email: [email protected]

Patient Mix in Outpatient

Surgery Settings and

Implications for MedicarePayment Policy

Chad D. Meyerhoefer1, Margaret S. Colby2,

and Jeffrey T. McFetridge1

Abstract

In 2008, Medicare implemented a new payment policy for ambulatory surgical centers(ASCs), which aligns the ASC payment system with that used for hospital outpatientdepartments and reimburses ASCs approximately 65% of what hospitals receive for thesame outpatient surgery. The authors assess patient selection across ASCs and hospitaloutpatient departments for four common surgeries (colonoscopy, hernia repair, kneearthroscopy, cataract repair), using data on procedures performed in Florida from 2004

to 2008. The authors construct measures of patient illness severity and cost risk and findthat ASCs benefit from positive selection. Nonetheless, the degree of selection varies bysurgery type and patient population. While similar studies in other states are needed, thefindings suggest that modifications to the Medicare outpatient payment system may beappropriate to account for the different populations that each setting attracts.

Keywords

Medicare, ambulatory surgery center (ASC), outpatient surgery, payment policy

Ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) are freestanding outpatient facilities that are typi-

cally owned by physicians and dedicated to providing a specialized service, such as

cataract repair or colonoscopy. In recent years, the number of ASCs nationwide has

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

3/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 63

grown dramatically, providing greater competition for hospital-owned outpatient

departments (HOPDs) that perform the same types of procedures (Iglehart, 2005). In

2008, there were approximately 5,200 Medicare-certified ASCs, up from just 3,000 in

2000, and the volume of ASC services per fee-for-service beneficiary has recentlygrown by more than 10% per year (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission [Med-

PAC], 2010).

Observers have attributed the growth in ASCs to favorable payment rates for

surgical services, health plans shift away from selective contracting, advances in

technology that have made more types of surgery feasible at outpatient facilities, and

physicians desire for increased autonomy relative to the hospital setting (Casalino,

Devers, & Brewster, 2003; Iglehart, 2005; MedPAC, 2003; Russo, VanLandegem,

Davis, & Elixhauser, 2006). Growth in procedure volume may reflect that ASCs

often offer beneficiaries more convenience in terms of location, surgery scheduling,and waiting times (MedPAC, 2010). However, physician ownership and limited

regulation of self-referral may also offer a financial incentive to provide more

surgical services; 96% of Medicare-certified facilities in 2008 were for-profit

(Chukmaitov, Menachemi, Brown, Saunders, & Brooks, 2008; Hollingsworth et al.,

2010; Koenig, Doherty, Dreyfus, & Xanthopoulos, 2009; MedPAC, 2010; Plotzke

& Courtemanche, 2010).

A new Medicare reimbursement system for ASCs, first implemented in January

2008 and fully phased in by 2011, makes significant headway in aligning historically

separate payment systems across the ASC and HOPD settings. Generally, the newsystem pays ASCs a percentage of what an HOPD would receive to perform each

procedure (MedPAC, 2007). The new system also expands the list of surgical proce-

dures that can be reimbursed at ASCs in recognition of the advances in medical care

that have made the ASC setting safe for more procedures (Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services [CMS], 2007; MedPAC, 2007).1

New Contribution

Although the new system aligns ASC and HOPD reimbursements, it may warrantfurther refinements. For example, it is unclear whether, across the wide variety of

procedures now performed on an outpatient basis, the method appropriately risk

adjusts for the different patient mix these two settings may attract (Winter, 2003).

Determining whether ASCs and HOPDs serve comparable patient populations and

whether the degree of selection is comparable across procedure types are important

factors in setting future Medicare payment policies, including the appropriate rela-

tive payment rate difference across outpatient venues. However, if differential

selection exists, policy makers need to know whether it results from patient prefer-

ences or physician behavior in order to formulate appropriate regulatory or programreforms.

In this article, we present evidence of differential patient selection across outpa-

tient surgery settings for four common types of outpatient surgeries using data on

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

4/22

64 Medical Care Research and Review69(1)

procedures performed in Florida from 2004 to 2008. In doing so, we use panel data

methods to determine whether positive selection exists at ASCs even after controlling

for established patterns of physician referral and other confounding factors. We also

investigate the degree to which differences in diagnosis coding across care settingsaffects determinations of risk selection. Overall, we find positive selection at ASCs

that varies by procedure type and across the Medicare and under-65 privately insured

populations. However, our indications of selection change when we consider groups

of patients with only one or two reported diagnoses, which suggest that judgments

regarding the extent of selection require assumptions about coding differences across

settings.

Medicare ASC Payment Policies

Prior to 2008, the 2,500 procedures that Medicare reimbursed in an ASC setting were

assigned to one of nine payment groups, each containing a diverse set of clinical

procedures. All procedures in the group received the same reimbursement rate, rang-

ing from $333 to $1,339 across the nine groups in federal fiscal year 2003. These

rates were based on cost and charge data collected in a 1986 survey that was annually

adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index through 2003.2 In contrast,

Medicare has paid HOPDs using the outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS)

since August 2000. Under OPPS, surgical procedures are aggregated into more than

800 payment groups, called ambulatory payment classifications (APCs), which arebased on cost and clinical similarity. Each procedure in these groups is also paid the

same rate (U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2006).

Because HOPD and ASC rates were determined and updated differently, by the

early 2000s, a number of procedures were reimbursed at a higher rate in the ASC set-

ting than in the HOPD setting. To adjust for this, the Medicare Prescription Drug,

Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 froze reimbursement rates to ASCs

through 2009, while the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 further limited payments to

ASCs, capping ASC reimbursement at the HOPD rate while the CMS revised the

ASC Medicare payment system (CMS, 2007; Iglehart, 2005; Winter, 2003).In August 2007, CMS released a final rule that changed ASC reimbursement under

Medicare, effective January 2008. Consistent with a GAO report that found that exist-

ing APC groups for HOPDs accurately reflect the relative (but not absolute) costs

of different procedures performed at ASCs, ASC payments are now based on APC

groups (GAO, 2006). Under the specific methodology proposed, CMS estimated that

ASCs would be paid approximately 65% of what a hospital would receive for per-

forming a procedure in the same APC group (MedPAC, 2007). To prevent reimburse-

ment rates from changing too quickly and disrupting facility finances, CMS proposed

a phased-in adjustment to the new payment system. In 2008, facilities received 25% oftheir payment based on the new system and 75% of their payment based on the old

system. In 2009, this changed to a 50/50 split and then a 75/25 split in 2010, before

payments become fully based on the new system in 2011 (CMS, 2007). Future updates

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

5/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 65

to the ASC payment rates will be made in conjunction with OPPS revisions, ensuring

that the two systems remain harmonized going forward (CMS, 2007).

Perspectives on ASCHOPD Payment Differentials

If ASC costs are generally lower, reimbursing them less than HOPDs for the same

category of procedure (APC group) offers a potential savings opportunity, both for

the Medicare program and its beneficiaries, who pay 20% coinsurance on each proce-

dure under traditional Medicare.3Indeed, advocates of ASCs suggest that they have

the potential to decrease costs and increase quality through economies of scale and a

concentrated management focus (Casalino et al., 2003; Shactman, 2005). For exam-

ple, they may be able to achieve lower total costs through more efficient staffing,

better space utilization, and lower overhead expenses. In 2004, GAO conducted whatis still the most recent thorough ASC cost survey completed since the 1986 rate-

setting survey, and it confirmed that for the 20 most common outpatient procedures

among Medicare beneficiaries, services performed in ASCs had substantially lower

costs than those same services performed in HOPDs (GAO, 2006).

The ability to provide services at lower cost is one of the reasons why ASCs are

exempt from laws prohibiting physicians from referring patients to facilities in which

they have an ownership interest (Gabel et al., 2008; Shactman, 2005).4However, prior

research has suggested that this exemption to self-referral laws may contribute to posi-

tive selection at ASCs, whereby physician-owners of ASCs practice cream skimmingand dumping (Ellis, 1998; Plotzke & Courtemanche, 2010; Strope et al., 2009). The

latter occurs when physicians refer potentially more complex and costly cases to

HOPDs, while the former occurs when they refer or treat patients with lower cost risk

at ASCs. This phenomenon provides an additional justification for relatively lower

payments to ASCs.

However, an ideal system for outpatient surgery payments would reimburse HOPDs

and ASCs at the same rate for a given level of quality, after adjusting for differences in

patient mix and the reliability of patient reimbursement. In addition, higher levels of

reimbursement could correspond to higher demonstrated quality. Under such a system,providers would have an incentive to produce a given level of quality most efficiently

(thereby increasing their profit margins) and to invest in systems and technologies to

improve quality in order to qualify for higher payments (Winter, 2003).5

Now that the initial process of aligning ASC and HOPD payments is nearly com-

plete, it is worth reassessing whether the new system adequately captures important

variation in patient selection to inform future modifications to Medicare outpatient

surgery payments. In particular, using an APC-based payment system in both settings

implies uniform risk adjustment across procedures in HOPDs and ASCs. However,

within some procedure groups, selection across venues may occur more strongly thanin others. For example, very little cross-venue patient selection might be expected for

procedures such as cataract removal, which have long been performed on an outpatient

basis, are relatively similar for all patients, and carry a low overall risk of complication

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

6/22

66 Medical Care Research and Review69(1)

(Sloss, Fung, Wynn, Ashwood, & Stoto, 2006). Other procedures, such as hernia sur-

gery, have more variant risks of complication and a shorter history of being performed

in the outpatient setting; for these kinds of procedures, we might expect much stronger

cross-venue patient selection.These examples imply different ideal cross-venue relative payment rates for each

procedure type. While, on average, benchmarking ASC reimbursements to 65% of

HOPD reimbursements may be appropriate, a single payment ratio fixed at 65% for

all procedures may not be. Where selection within a procedure type is weak, ASC and

HOPD reimbursement rates might appropriately be quite close, but where selection is

stronger, the ASC-HOPD differential should be greater (assuming equivalent quality

in both settings).

Conceptual Framework for Patient Venue Selection

The process that leads consumers to demand medical services is significantly more

complicated than most other consumer services. This is because physicians act as

gatekeepers of both the nature and place of the service provided. Therefore, differen-

tial selection across outpatient surgery venues can be generated by consumers, provid-

ers, or both.

As a result of the disutility consumers experience from sickness, and the ability of

higher quality medical services to more quickly return them to good health, consumers

will demand more services from higher quality providers. Those with the most severeconditions will have the strongest preferences for quality, resulting in adverse selec-

tion toward the highest quality providers (Beaulieu, 2002; Phelps, 2003). Therefore, if

either the distribution of illness severity or the relative quality of ASCs-to-HOPDs

differs across outpatient procedures, consumer preferences for quality can generate

differential selection. While ASCs may be able to achieve economies of scale through

specialization, HOPDs are able to achieve economies of scope. In general, we expect

that patients who perceive higher risks of complications from surgery, due to the

severity of their diagnosis, the intensity of the procedure to be performed, their age, or

their underlying risk factors, may be more likely to be treated at a hospital, due to theavailability of auxiliary services and emergency care.

On the provider side, if physicians acted as perfect agents for their patients, they

would recommend the level of medical care necessary to return the patient to full

health and no more. However, physicians have incentives to induce additional demand

beyond what is medically necessary in order to increase their earnings. This takes the

form of direct inducement for the services they provide and indirect inducement for

ancillary services at facilities in which they have an ownership stake (Mitchell & Sass,

1995). Since ASCs are predominantly physician-owned, they are subject to both direct

as well as indirect inducements. The latter may exist even if physicians have admittingrights to both an ASC and HOPD because treatment at an ASC in which the physician

has an ownership stake would result in a total payment of not only the physician fee

but a percentage of the facility fee as well.

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

7/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 67

One of the most widely cited economic models of physician demand inducement

suggests that the level of inducement will vary in accordance with several factors

(Dranove, 1988). First, as the patients own diagnostic skill increases, physicians

will lower the level of inducement. This is because fewer patients will consent to theadditional treatment, and physicians do not want to develop a reputation for recom-

mending unnecessary procedures. Second, if either the cost to the patient decreases

or the value of the procedure increases, physicians will increase the level of induce-

ment as patients are more willing to consent to additional treatments. For example,

if sicker, more complex patients select into health insurance plans with lower out-of-

pocket costs, this could lead to greater physician-induced demand that is correlated

with illness severity. Therefore, differences in patient diagnostic skill, relative costs,

and relative value could all lead to varying levels of physician inducement across

outpatient procedures.More generally, Ellis (1998) has shown that prospectively paid providers have an

incentive to overprovide services to low-severity patients (creaming) and underpro-

vide services to high-severity patients (skimping). While both ASCs and HOPDs are

reimbursed in this manner, physician ownership intensifies such incentives at ASCs

(Hollingsworth et al., 2010; Plotzke & Courtemanche, 2010; Strope et al., 2009).

However, Elliss model also suggests that increased competition between ASCs and

HOPDs will mitigate the dumping of high-severity patients at HOPDs and concur-

rently lead to an expansion of services to low-severity patients through greater physi-

cian inducement at both venues. Therefore, differences in the level of competitionbetween ASCs and HOPDs across procedures can also generate differences in risk

selection.

Overall, while the results of these economic models provide insight into the under-

lying causes of differential patient selection at ASCs and HOPDs, in theory, either

facility can experience positive selection. Therefore, the exact degree of risk selection

across procedures and facilities is an empirical question, but one that should be pur-

sued while accounting for market-level factors, such as the degree of competition

between facilities, patient costs and characteristics, and physician characteristics and

affiliations. Adjusting prospective payments for patient selection is particularly impor-tant, otherwise physicians will not have the proper incentives to refer and treat patients

in the most cost-effective setting. If payments are not risk adjusted, physicians who

practice outpatient surgery will have a strong financial incentive to practice cream

skimming, skimping, and dumping.

Data and Methodology

To evaluate the extent of patient selection across outpatient surgery venues, we

analyzed four common outpatient surgical procedures performed in Florida in 2004through 2008: knee arthroscopy, hernia surgery, colonoscopy, and cataract surgery.6

The data we used were collected by the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration

(AHCA), and the procedures we examined were among the most common in Florida.

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

8/22

68 Medical Care Research and Review69(1)

The AHCA facility categorizations allowed us to identify whether each procedure was

performed in an ASC or HOPD. We then used age and primary payer codes from the

AHCA analytic file to limit the sample to two groups: patients aged 65 years and older

who comprise the bulk of the Medicare population and, as a comparison group,patients aged 65 years and younger with private insurance. One reason for considering

the latter is that the structure of reimbursements is more variable across private insur-

ers. As a result, investigating risk selection among this group and comparing it with

the Medicare population provides some indication of whether the selection effects we

observe for Medicare patients are highly dependent on the current structure of reim-

bursements. The final sample for the Medicare and privately insured populations

combined accounted for 4,051,517, or approximately 28% of all the outpatient proce-

dures performed in Florida during the sample period.

We use linear probability models to predict the probability that a patient is treatedat an ASC instead of an HOPD, as a function of patient, market, and facility character-

istics as well as physician and year fixed effects. The primary regressors of interest in

our models are comprehensive measures of patient cost risk and illness severity based

on the Diagnosis Cost Groups/Hierarchical Condition Categories (DCG/HCC)

method.7DCG/HCC risk scores are derived from data on patient age, gender, and

physician-reported diagnosis codes (ICD-9-CM; U.S. National Center for Health

Statistics, 2006). They have been validated as a proper measure of risk adjustment

when modeling health outcomes in both the inpatient setting (Ash et al., 2003; Petersen,

Pietz, Woodard, & Byrne, 2005) and the outpatient setting (Chukmaitov, Menachemi,Brown, Saunders, & Brooks, 2008; Chukmaitov, Harless, Menachemi, Saunders, &

Brooks, 2009). DCG/HCC risk scores have also been used by the CMS to risk adjust

Medicare payments to private insurers under Part C (Pope et al., 2000; Pope et al., 2004).

To compute these scores from the 2004-2008 AHCA outpatient surgery data, we

followed the methodology of Pope et al. (2000) and implemented their algorithms

using SAS, version 9.1, statistical software. The risk scores are computed through a

multiple-step process that begins by mapping reported ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes to

one of several clinically related condition categories. The condition categories are then

hierarchically grouped and ranked based on their relationship to reported costs. Sincethe AHCA data only contain information on facility-reported charges, we merged in

Medicare reimbursement levels from the OPPS corresponding to each procedure and

use these as our measure of treatment cost. Linear regression is used to determine the

relationship between the hierarchical condition categories and cost in order to calcu-

late condition weights. These weights are then used to translate each patients reported

conditions into a continuous risk score, which defines the distribution of cost risk for

the sample.

We computed the risk scores separately for the Medicare and under-65 privately

insured populations and normalized the scores across the sample of patients in eachpopulation undergoing the four outpatient procedures.8As a result, the average levels

of the scores are comparable across the four procedures we examined. In our empirical

models, we enter dummy variables indicating whether the patients risk score was in

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

9/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 69

the 26th to 50th, 51st to 75th, or 76th to 100th percentile of the procedure-specific riskdistribution, with the lowest risk patients serving as the comparison group.

Previous research that applied the DCG/HCC risk adjustment method to earlier

waves of the AHCA data identified the potential underreporting of secondary and

additional diagnoses at ASCs as a factor that may influence determinations of risk

selection (Chukmaitov, Menachemi, Brown, Saunders, & Brooks, 2008; Chukmaitov

et al., 2009). We investigated this possibility in our data and likewise found that ASCs

report fewer additional diagnoses than HOPDs. As shown in Table 1, the average

number of additional diagnoses reported at HOPDs is higher than at ASCs for all four

procedures. However, with the exception of cataract surgery, ASCs report at least oneadditional diagnosis for the average Medicare patient. If ASCs typically treat patients

with fewer comorbidities and complications, this is to be expected. Nonetheless, ASCs

may systematically underreport additional diagnoses because the structure of ASC

reimbursements provides less incentive to provide exhaustive documentation of all the

patients conditions than at HOPDs.9Similar to earlier work, we test the sensitivity of

our results to the number of reported diagnoses that enter the risk score computation.

We use the full sample of patients who received outpatient surgery in Florida and

all their reported diagnoses to calculate the weights in the risk score computation.

However, we estimate our models separately on three groups of patients: (a) patientswith only a primary diagnosis reported, (b) patients with either a primary or a primary

and one secondary diagnosis reported, and (c) the full sample of patients with any

number of reported diagnoses. If physicians at HOPDs code more secondary diagno-

ses than physicians at ASCs irrespective of the patients actual illness severity, then

we expect to observe different patterns of selection across these three groups. In par-

ticular, HOPD patients with only a primary diagnosis should be among the healthiest

patients treated at that venue, but ASC patients with only a primary diagnosis should

still be relatively representative of full ASC patient population. (Patients at HOPDs

with serious primary conditions are significantly more likely to have secondary condi-tions, which HOPD physicians would have recorded.) Therefore, estimating models

using the subsample of patients with just a primary (or primary and one secondary)

diagnosis allows us to stack the deck in favor of finding negative selection at ASCs.

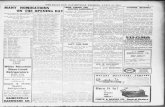

Table 1.Mean Number of Secondary Diagnoses Reported at ASCs and HOPDs (Standard

Deviations in Parenthesis)

Medicare Privately Insured

ASC HOPD ASC HOPD

Knee arthroscopy 1.73 (1.32) 4.05 (2.26) 1.50 (1.23) 2.58 (1.89)

Hernia surgery 2.92 (0.91) 2.92 (2.28) 0.34 (0.73) 1.43 (1.59)

Cataract surgery 0.24 (0.67) 2.49 (2.46) 0.24 (0.68) 2.39 (2.35)

Colonoscopy 1.19 (1.43) 3.63 (2.33) 1.08 (1.31) 2.80 (2.01)

Note: ASC =ambulatory surgery center; HOPD =hospital-owned outpatient department.

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

10/22

70 Medical Care Research and Review69(1)

If, however, we continue to find positive selection at ASCs even when using the

restricted sample, this provides very strong evidence that differential coding norms

across venues are not leading us to draw exaggerated conclusions about the extent of

positive selection at ASCs.Another way that we account for differences in coding norms across ASCs and

HOPDs is by exploiting the fact that the AHCA data contain multiple observations

on most physicians. This allows us to include physician fixed effects in our empiri-

cal models to control for unobservable but potentially confounding physician

behaviors that are reasonably time-invariant. Other than coding norms, fixed effects

also control for the propensity of physicians to induce demand for a particular pro-

cedure or systematically refer patients to ASCs as opposed to HOPDs. Furthermore,

by conditioning on payment group indicators for procedures with multiple reim-

bursement levels and estimating our models with and without physician fixedeffects, we can infer how risk selection is influenced by unobserved physician

behaviors.

The other variables we include in our models are intended to control for differences

in facility quality, market conditions, and patient demographics. Though facility quality

and reputation are notoriously difficult to measure, previous studies have indicated that

quality is broadly associated with the number of procedures performed (Chukmaitov,

Menachemi, Brown, Saunders, Tang, et al., 2008; Halm, Lee, & Chassin, 2002;

Stavrakis, Ituarte, Ko, & Yeh, 2007). Therefore, we include two facility-level measures

of procedure volume to capture potentially important quality and reputational effects.First, we constructed the weighted average physician volume at a given facility, where

the weights are the proportion of the procedures at the facility performed by each physi-

cian. This variable is a proxy for the level of surgeon skill and experience patients can

expect by seeking care at the facility.10Our second measure is the total annual number

of procedures performed at each facility, which is intended to capture overall system

quality and the likelihood of systems errors.

We also constructed a measure of ASCHOPD competition in each patients hos-

pital referral region (the relevant market area; Dartmouth Health Atlas, 2008).11The

ASC market penetration rate is defined as the number of procedures (i.e., colonosco-pies) performed in ASCs divided by the total number of procedures performed in both

ASCs and HOPDs. We include this variable to account for the fact that patients in

areas with a higher concentration of ASCs may be more likely to use their services due

to greater ASC visibility and geographic proximity (Bian & Morrisey, 2007) and to

account for the impact of competition on relative costs.

Although we estimated our models separately on the Medicare and under-65 pri-

vately insured populations to limit heterogeneity in insurance coverage, this clearly

does not account for all coverage differences. Therefore, we used information on the

primary payer for each claim to derive other insurance variables. For the over-65Medicare population, we created an indicator for Medigap/retiree coverage if the pri-

mary payer was a private insurer and an indicator for dual eligibility if the primary

payer was Medicaid. For both the over-65 Medicare population and the under-65

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

11/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 71

privately insured population we created variables to denote whether the patient was

enrolled in a managed care plan (health maintenance organization or preferred pro-

vider organization). Finally, our models also control for basic patient demographics,

including age, gender, and ethnicity, and include year fixed effects to control formacro-level time varying, but individual invariant aspects of the economic and policy

environment.

Results

The distribution of procedures across the two outpatient surgery venues, reported in

Table 2, varies widely across the four surgeries we examined. While 89% of cataract

surgeries performed on Medicare patients took place in ASCs, only 24% of hernia sur-

geries were performed at ASCs. Likewise, the average facility performing colonosco-pies completed more than 3,200 procedures annually during the sample period, whereas

the average facility performing hernia repairs completed fewer than 150 per year.

The DCG/HCC risk scores indicate that the average cost risk is highest for knee

arthroscopy patients and lowest for those undergoing hernia repair. Computing

the scores for the subsample of patients with fewer diagnosis codes does not alter

relative ranking of cost risk across procedures, though it does eliminate most differ-

ences in average risk between patients treated at ASCs and HOPDs. In contrast, the

level of average risk is significantly higher at HOPDs than ASCs when the risk scores

are computed using the full patient populations for each procedure. The volume mea-sures also vary considerably by facility type. In particular, the average physician

practicing at an ASC has higher volume than the average HOPD physician, and ASCs

have higher overall volumes.

In Table 3, we report the percentage change in the probability that a patient selects

an ASC due to an increase in the patients risk score above the lowest risk category,

while in Table 4 we report the full set of regression parameters corresponding to the

Medicare population. We corrected the standard errors for these and all other regression-

based statistics by clustering at the facility level. When we estimate our models using

the full sample of patients undergoing each procedure, we find consistent evidencethat ASCs benefit from a healthier patient population than HOPDs. Patients in higher

quartiles of the risk distribution, and particularly the top quartile, are less likely to seek

treatment at ASCs. Furthermore, the degree of risk selection varies across procedures

and across patient populations. Among Medicare patients, those in 76th to 100th per-

centile of the risk distribution are 76% less likely to select an ASC for hernia repair but

only 10% less likely to have cataract surgery at an ASC. With the exception of cataract

surgery, we find that positive selection at ASCs is greater among the Medicare popula-

tion than the under-65 privately insured.

As expected, limiting the sample to patients with only a primary and one second-ary diagnosis, or just a primary diagnosis, limits the degree of positive selection

found at ASCs. In most cases, cross-venue differences in cost risk are no longer

statistically different for these models, and in some cases, such as for privately

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

12/22

-

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

13/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 73

insured knee arthroscopy and colonoscopy patients, ASCs appear to experience

negative (or adverse) selection. Other researchers have found that computing DCG/

HCC risk scores using the primary versus all the diagnosis information in the

AHCA data leads to different judgments with regard to the relative risk of certain

patient groups (Chukmaitov, Menachemi, Brown, Saunders, & Brooks, 2008;

Chukmaitov et al., 2009). They recommend using all available diagnoses to com-

pute the risk scores.We present results for the subsamples of patients with fewer reported diagnosis as

a test of whether differences in coding norms across venues may influence our conclu-

sions. The fact that we continue to find positive selection into treatment at ASCs for

cataract and hernia surgery when the sample is limited to those with no more than two

reported diagnoses provides added support to conclusions we draw using the full sam-

ple. However, our findings for knee arthroscopy and colonoscopies are less robust in

this regard. Given the potential for physicians at ASCs to fail to record some important

additional diagnoses, we suggest using the results based on the full sample as upper

bounds on the degree of favorable selection at ASCs.Overall, the selection effects for the Medicare population presented in Table 3 indi-

cate that there is substantial positive selection into treatment at ASCs by hernia

patients, moderate selection by knee arthroscopy and colonoscopy patients, and some-

what more limited selection by cataract patients. Among the under-65 privately insured

population, ASCs also experience the greatest degree of positive selection among her-

nia patients. However, they exhibit greater selection by privately insured cataract

patients than those undergoing knee arthroscopies or colonoscopies. For both patient

populations, patterns of positive selection at ASCs by cataract patients are most robust.

Table 5 contains percentage changes in the probability that a patient selects an ASCfor a 1% change in market or facility characteristics (i.e., elasticities). The elasticities

are similar across the two patient populations but vary substantially across procedures

in some cases. A 10% increase in the average physician volume at hernia surgery

KneeArthroscopy

HerniaSurgery

CataractSurgery Colonoscopy

Weighted average of physicianvolume/facility

ASC 168 64 1,100 903

HOPD 137 46 399 731

Annual number of procedures perfacility

ASC 652 118 2,277 4,412

HOPD 340 160 956 1,812

Note: ASC =ambulatory surgery center; HOPD =hospital-owned outpatient department.

Table 2. (continued)

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

14/22

Table3.P

ercentageChangeintheProbabilityofSelectinganASCby

RiskCategory

Medicare

Private

NumberofDiagnoses

26th-50th

Percentile

51st-75th

Percentile

7

6th-100th

Percentile

26th-50th

Percentile

51st-75th

percentile

7

6th-100th

Percentile

Kneearthr

oscopy

Anynum

ber

0.84(1.57)

8.17**(2.03)

16

.01**(2.44)

2.69^(1.43)

1.33(1.48)

4.19*(1.94)

Primary/secondary

0.06(0.71)

1.46(1.17)

0.68(1.34)

0.63(0.88)

4.48**(1.52)

3

.84**(1.42)

Primary

0.77(0.63)

0.10(0.91)

0.42(1.31)

0.58(0.73)

3.09*(1.25)

3.57*(1.50)

Herniasurgery

Anynum

ber

10.20**(2.26)

72.30**(7.47)

75

.89**(7.62)

4.84*(2.11)

28.29**(3.89)

45

.89**(5.22)

Primary/secondary

6.12**(1.27)

6.03**(1.67)

17

.54**(4.68)

4.35*(1.90)

0.74(2.28)

20

.87**(5.78)

Primary

0.92(0.85)

3.66(2.29)

2.31(2.27)

0.20(2.14)

0.87(3.05)

6.09^(3.16)

Cataractsurgery

Anynum

ber

1.79**(0.31)

3.01**(0.52)

10

.11**(1.49)

1.12**(0.39)

2.90**(0.79)

11

.91**(1.81)

Primary/secondary

0.63**(0.16)

0.96**(0.23)

2

.75**(0.56)

2.77**(0.63)

0.03(0.41)

3

.86**(0.91)

Primary

0.07(0.05)

0.00(0.01)

0.01(0.10)

1.10(0.71)

0.68(0.48)

1.73^(1.02)

Colonosco

py

Anynum

ber

7.03**(0.78)

1.90**(0.40)

17

.61**(1.48)

0.54(0.43)

4.99**(0.59)

5

.03**(0.97)

Primary/secondary

0.62**(0.16)

0.38*(0.17)

0.00(0.22)

1.16**(0.24)

1.23**(0.31)

3

.29**(0.55)

Primary

0.37**(0.10)

0.03(0.08)

0.08(0.10)

0.76**(0.15)

1.40**(0.26)

2

.29**(0.43)

Note:Standarderrorsinparenthesisarecluster-correctedatthefacilitylevel.

**,*,^Indicatestatisticalsignificanceatthe1%,

5%,and10%level,respectively.

74

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

15/22

Table4.R

egressionParametersforMe

dicareModelsBasedonFullS

ample

Knee

Arthroscopy

HerniaSurgery

CataractSurgery

Co

lonoscopy

DCG/HCC

riskvariables

26th-50thpercentileofriskdistributio

n

0.005(0.010)

0.024**(0.006)

0.016**(0.003)

0.0

51**(0.005)

51st-75t

hpercentileofriskdistributio

n

0.052**(0.013)

0.173**(0.018)

0.027**(0.005)

0

.014(0.003)

76th-100thpercentileofriskdistribution

0.101**(0.015)

0.182**(0.018)

0.090**(0.013)

0.1

27**(0.010)

Marketand

facilitycontrols

Logofw

eightedphysicianvolume

0.142**(0.046)

0.365**(0.045)

0.024(0.022)

0

.040(0.043)

Logoftotalfacilityvolume

0.226**(0.024)

0.149**(0.028)

0.146**(0.017)

0.2

63**(0.016)

ASCpen

etrationrate

0.990**(0.221)

0.780**(0.170)

0.476**(0.185)

0.9

80**(0.200)

Demographiccontrols

Female

0.005*(0.002)

0.018**(0.004)

0.018**(0.003)

0.0

15**(0.001)

Olderth

an75

0.014**(0.003)

0.041**(0.005)

0.022**(0.004)

0.0

29**(0.002)

Black

0.012^(0.007)

0.011(0.007)

0.004(0.004)

0.0

26**(0.006)

Hispanic

0.012(0.007)

0.056*(0.028)

0.017^(0.010)

0.014*(0.006)

Otherrace

0.037**(0.012)

0.045**(0.017)

0.023*(0.009)

0.024*(0.009)

Racemissing

0.076**(0.021)

0.057*(0.027)

0.021**(0.008)

0.0

50**(0.013)

Insurancecontrolsandpaymentgroup

HMO

0.067**(0.011)

0.040**(0.001)

0.022**(0.006)

0.017^(0.009)

Medigap

0.063**(0.009)

0.087**(0.011)

0.019**(0.005)

0.0

72**(0.011)

Dualelig

ible

0.016(0.029)

0.035(0.029)

0.012(0.009)

0

.001(0.014)

Payment

Group4

0.010^(0.006)

Payment

Group7

0.024**(0.005)

Payment

Group9

0.055**(0.009)

Note:DCG/HCC=D

iagnosisCostGroups/HierarchicalConditionCategories;ASC=ambulatorysurgerycent

er;HMO=healthmaintenanceo

rganization.

Standarderrorsinparenthesisarecluster-correctedatthefacilitylevel.Allregressionsincludephysicianandyearfixedeffects.

**,*,^Indicatestatisticalsignificanceatthe1%,

5%,and10%level,respectively.

75

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

16/22

76 Medical Care Research and Review69(1)

Table 5.Percentage Change in the Probability of ASC Selection for a 1% Change in Market

or Facility Characteristics

Knee

Arthroscopy

Hernia

Surgery

Cataract

Surgery Colonoscopy

Medicare

Weighted physician volume 0.22** (0.07) 1.52** (0.18) 0.03 (0.03) 0.06 (0.06)

Facility volume 0.36** (0.04) 0.62** (0.12) 0.16** (0.02) 0.36** (0.02)

ASC penetration rate 0.98** (0.22) 0.83** (0.17) 0.47** (0.02) 0.97** (0.19)

Private

Weighted physician volume 0.11 (0.09) 1.36** (0.18) 0.01 (0.03) 0.07 (0.07)

Facility volume 0.44** (0.04) 0.90** (0.12) 0.20** (0.02) 0.39** (0.03)

ASC penetration rate 1.04** (0.21) 0.67** (0.16) 0.59* (0.27) 1.07** (0.23)

Note: ASC =ambulatory surgery center. Standard errors in parenthesis are cluster-corrected at thefacility level.**,*,^Indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively.

centers increases the probability of ASC selection by 15%, but similar increases in

volume at centers that perform cataract surgeries or colonoscopies have no effect on

the probability patients select ASCs. With the exception of hernia surgery, overall

facility volume, rather than average physician volume, appears to be a more importantdeterminant of ASC selection. For knee arthroscopy, cataract surgery, and colonos-

copy, higher facility volumes increase the probability of ASC selection, but for hernia

surgery, patients are more likely to seek treatment at ASCs staffed by a small number

of high-volume physicians. Finally, patients are more likely to select ASCs in markets

with greater ASC penetration, particularly in the case of colonoscopy and knee

arthroscopy.

Discussion

Our results suggest that patient selection in the Medicare population across outpatient

surgery venues varies by procedure. Among the four outpatient surgeries we exam-

ined, ASCs experienced a significant degree of positive selection among hernia

patients, a moderate degree of positive selection among knee arthroscopy and colo-

noscopy patients, and slightly more limited, but persistent selection among cataract

patients. These results provide compelling evidence to spur additional investigation

into the scope of the cross-venue selection problem in other areas of the United States.

While quality data are currently unavailable for ASCs, MedPAC has recommended

that CMS begin requiring ASCs to report quality metrics beginning in 2011 as a con-dition for receiving increased reimbursement rates (MedPAC, 2010). In the future,

such data should be analyzed jointly with information on patient selection to assess

the overall efficiency of ASCs relative to HOPDs.

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

17/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 77

If quality is fairly uniform across care settings, adjusting the ASCHOPD payment

differential to account for patient selection could encourage continued migration of

care to the most efficient setting. To the extent that the differences in patient mix we

observe translate into differences in the costs of performing an average outpatientprocedure, the appropriate ASCHOPD payment differential should be smaller for

procedures with limited evidence of selection and higher for procedures characterized

by significant positive selection into ASCs. However, we acknowledge that quantify-

ing how illness severity translates directly into higher costs in the outpatient setting is

also a critical challenge for future work (Friedman, Jiang, Elixhauser, & Segal, 2006;

Yu, Revalo, & Wagner, 2003).

Though there are advantages to a risk-adjusted system, it bears considering whether

modification of the current payment system would entail undue administrative com-

plexities. Indeed, in its evaluation of relative ASC and HOPD costs, GAO (2006)noted that an advantage of basing ASC reimbursements on the OPPS would be elimi-

nating the need for ASC surveys and annual revision of the ASC payment groups.

While we acknowledge administrative concerns, we suggest that modifications to the

ASC payment system might strike a compromise between the extremes of technical

precision and administrative simplicity.

For example, APC groups might be further aggregated into three or four categories

along the dimension of risk selection and a different cross-venue payment differential

set for each group. This differential would be smaller than 65% for APC groups devoid

of selection and greater than 65% for APC groups where positive selection occurs,with the goal of maintaining budget neutrality. Without this type of adjustment, the

new payment policy may reimburse ASCs at a level well above their cost for some

procedures, but underpay them for others, further exacerbating incentives for physi-

cians to selectively refer low-severity patients to ASCs for some procedures. Removing

such distortions has the potential to encourage care to flow to the most efficient setting

and increase the cost-effectiveness of surgeries purchased by Medicare.

Although our results raise important concerns about the current payment system,

additional research is needed before definitive policy recommendations can be made.

First, we analyze data from the state of Florida, but evidence from a larger number ofmarket areas is necessary to determine whether there are systematic differences in risk

selection across geographic regions. In addition, current practice in diagnosis coding

at ASCs makes it difficult for us to determine the exact degree of positive selection at

ASCs. Rather, we can only identify plausible upper bounds on selection effects.

Discrepancies in diagnosis coding norms between ASCs and HOPDs are problem-

atic because metrics based on diagnosis codes are used to risk adjust Medicare Part C

payments and set ACCHOPD payment differentials. One priority of future research

should be to determine whether the transition of ASCs to the OPPS from 2008 to 2011

and corresponding expansion of reimbursable procedures at ASCs has reduced codingdiscrepancies. This might include studies that incorporate chart review to provide a

better indication of the extent to which coding differences are due to variation in cod-

ing norms across settings as opposed to true differences in illness severity. Depending

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

18/22

78 Medical Care Research and Review69(1)

on the outcome of these studies, CMS could consider new policies to either further

standardize diagnosis coding or better enforce current standards and ideally coordinate

these with the proposed ASC quality reporting initiative scheduled to take effect in

2012 (CMS, 2010). No matter the approach, careful analysis of proposed reforms tocoding standards should be conducted to ensure that new requirements do not have

unintended negative consequences.

As medical technology continues to advance, the diversity of procedures performed

at ASCs is likely to increase, particularly under the new Medicare payment frame-

work. Under the prior payment system, only specifically enumerated procedures were

reimbursable at ASCs. In contrast, the system that was implemented in January 2008

takes a different conceptual approach and permits ASC reimbursement for any surgi-

cal procedure, except those explicitly excluded because they pose a significant safety

risk or require an overnight stay (CMS, 2007). Guidelines have been established todetermine which procedures currently pose a safety risk; however, improvements in

outpatient surgery in the coming years will surely shift expectations about safety,

broadening the set of procedures that Medicare reimburses in the ASC setting. Indeed,

newly covered services were responsible for 47% of the growth in ASC service vol-

ume from 2007 to 2008 (MedPAC, 2010).

With the role of ASCs in outpatient care continuing to develop, and new proce-

dures beginning to be performed in multiple settings, careful attention should be paid

to the issue of patient selection across venues and its implications for appropriate

reimbursement. Analyses presented here suggest that patient selection can occur verydifferently across just four surgical procedure types. Bringing HOPD and ASC pay-

ment systems into the same APC-based reimbursement framework was a significant

step forward in aligning market incentives to achieve more cost-effective care.

However, in this dynamic environment, policy makers should begin to investigate

how well the new payment system accounts for variation in patient selection to ensure

both adequate reimbursement and maximum value purchasing for the Medicare pro-

gram in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank CFACT seminar participants at the Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality for useful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship,

and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication ofthis article.

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

19/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 79

Notes

1. In both the HOPD and ASC settings, physicians professional services are reimbursed

according to the Part B Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. Therefore, legislated differences

in payments across settings are due to varying reimbursement for the cost of items and ser-vices furnished by the facility where the procedure is performed (such as surgical supplies,

equipment, and nursing services).

2. ASCs did not receive an annual inflation update from 2004 through 2009.

3. Among the reasons why HOPD costs may be higher, for example, are regulations that com-

pel them to provide services to indigent patients who may be relatively more expensive to

treat but less able to pay for services (Shactman, 2005).

4. Another reason for the exemption is that physicians perform most of the services in the

ASCs themselves. As a result, the potential for overuse is limited by the physicians ability

to only treat a certain number of patients in the workday. 5. Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that designers of the new payment system

faced several key constraints: (a) a legislative mandate for implementation by January

2008; (b) a requirement for cost neutrality; (c) few, if any, reliable means of tracking ASC

and HOPD quality and safety; and (d) limited information on patient selection across ven-

ues. In light of such constraints and the GAOs finding that ASCs have lower costs than

HOPDs, it is easy to see the appeal of an administratively simple solutionnamely, the

reimbursement of ASCs under the OPPS system, with a uniformly lower payment factor

than HOPDs.

6. We define knee arthroscopies as those procedures with CPT codes 29870-29887, herniasurgeries as having codes 49505-49525, colonoscopies as having codes 45378-45392, and

cataract surgeries as having codes 66830-66984. These procedures are reimbursable at

both ASCs and HOPDs.

7. It is not uncommon in the literature to characterize the DCG/HHC risk scores as measures of

illness severity, though what they directly measure is the cost risk associated with a particu-

lar condition. Since there is a high degree of coincidence between medical costs and illness

severity based on non-cost-based metrics, the former characterization is not misleading.

8. We also use Medicare OPPS reimbursement rates as our measure of treatment cost when

computing risk scores for the under-65 privately insured population to ensure that ourcomparisons of risk selection across the two populations are based on consistent measures.

9. Only secondary diagnoses in condition categories that are different from the primary diag-

nosis will generally increase a patients DCG/HCC risk score. This is because primary

diagnoses are typically higher in the hierarchical ranking of conditions than secondary

diagnoses within a given category.

10. Note that some of the procedures contributing to a physicians total volume may not have

been performed at the given facility but that the weight given to each physician is derived

using only procedures performed at that facility.

11. The Dartmouth Health Atlas (2008) defines a hospital referral region as the regional mar-ket for tertiary medical care requiring the services of a major referral center. These regions

are defined by determining where patients are most commonly referred for cardiovascular

surgical procedures and neurosurgery.

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

20/22

80 Medical Care Research and Review69(1)

References

Ash, A., Posner, J., Speckman, S., Franco, A., Yacht, C., & Bramwell, L. (2003). Using claims

data to examine mortality trends following hospitalizations for heart attack in Medicare.

Health Services Research, 38, 1253-1262.Beaulieu, N. (2002). Quality information and consumer health plan choices.Journal of Health

Economics, 21(1), 43-63.

Bian, J., & Morrisey, M. A. (2007). Free-standing ambulatory surgery centers and hospital sur-

gery volume.Inquiry, 44, 200-210.

Casalino, L. P., Devers, K. J., & Brewster, L. R. (2003). Focused factories? Physician-owned

specialty facilities.Health Affairs, 22(6), 56-67.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2007). CMS-1517-F: Revised payment system

policies for services furnished in ASCs beginning CY 2008 (72 Federal Register, 42470

2007-08-02). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2010). CMS fact sheet: Proposed 2011 policy, pay-

ment changes for hospital outpatient departments and ambulatory surgery centers. Wash-

ington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Chukmaitov, A. S., Harless, D. W., Menachemi, N., Saunders, C., & Brooks, R. G. (2009).

How well does diagnosis-based risk-adjustment work for comparing ambulatory clinical

outcomes?Health Care Management Science, 12, 420-433.

Chukmaitov, A. S., Menachemi, N., Brown, S. L., Saunders, C., & Brooks, R. (2008). A com-

parative study of quality outcomes in freestanding ambulatory surgery centers and hospital-

based outpatient departments: 1997-2004.Health Services Research, 43, 1485-1504.Chukmaitov, A. S., Menachemi, N., Brown, S. L., Saunders, C., Tang, A., & Brooks, R. (2008).

Is there a relationship between physician and facility volumes of ambulatory procedures and

patient outcomes?Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 31, 354-369.

Dartmouth Health Atlas. (2008). 2004 zip code to HSA and HRR crosswalk. The Dartmouth

Atlas of Health Care. Retrieved from http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/download

.aspx

Dranove, D. (1988). Demand inducement and the physician/patient relationship. Economic

Inquiry, 26, 281-298.

Ellis, R. (1998). Creaming, skimping and dumping: Provider competition on the intensive andextensive margins.Journal of Health Economics, 17, 537-555.

Friedman, B., Jiang, J., Elixhauser, A., & Segal, K. (2006). Hospital inpatient costs for adults

with multiple chronic conditions.Medical Care Research and Review, 63, 327-346.

Gabel, J., Fahlman, C., Kang, R., Wozniak, G., Kletke, P., & Hay, J. (2008). Where do I send

thee? Does physician-ownership affect referral patterns to ambulatory surgery centers?

Health Affairs, 27, W165-W174.

Halm, E. A., Lee, C., & Chassin, M. R. (2002). Is volume related to outcome in healthcare? A

systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature.Annals of Internal Medicine,

137, 511-520.Hollingsworth, J. M., Ye, Z., Strope, S., Krein, S., Hollenbeck, A. T., & Hollenbeck, B. K.

(2010). Physician-ownership of ambulatory surgery centers linked to higher volume of sur-

geries.Health Affairs, 29, 683-689.

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

21/22

Meyerhoefer et al. 81

Iglehart, J. K. (2005). The emergence of physician-owned specialty hospitals. New England

Journal of Medicine, 352, 78-84.

Koenig, L., Doherty, J., Dreyfus, J., & Xanthopoulos, J. (2009).An analysis of recent growth of

ambulatory surgical centers. Washington, DC: KNG Health Consulting.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2003). Section 2F: Assessing payment adequacy

and updating payments for ambulatory surgical center services(Report to Congress: Medi-

care Payment Policy). Washington, DC: Author.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2007).Ambulatory surgical centers payment system.

Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.medpac.gov/documents/MedPAC

_Payment_Basics_07_ASC.pdf

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2010). Section 2C: Ambulatory surgical centers

(Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy). Washington, DC: Author.

Mitchell, J., & Sass, T. (1995). Physician ownership of ancillary services: Indirect demandinducement or quality assurance?Journal of Health Economics, 14, 263-289.

Petersen, L., Pietz, K., Woodard, L., & Byrne M. (2005). Comparison of the predictive validity

of diagnosis-based risk adjusters for clinical outcomes.Medical Care, 35(11 Suppl.), 61-67.

Phelps, C. (2003).Health Economics. New York, NY: Addison Wesley.

Plotzke, M., & Courtemanche, C. (2010). Does procedure profitability impact whether outpa-

tient surgery is performed at an ambulatory surgery center or hospital?Health Economics,

20, 817-830. doi:10.1002/hec.1646

Pope, G. C., Ellis, R. P., Ash, A.S., Ayanian, J. Z., Bates, D. W., Burstin, H., . . . Wu, B. (2000).

Diagnostic cost group hierarchical condition category models for Medicare risk adjustment(Final Report to the Health Care Financing Administration Under Contract Number 500-95-

048). Waltham, MA: Health Economics Research.

Pope, G. C., Kautter, J., Ellis, R. P., Ash, A. S., Ayanian, J. Z., Lezzoni, L. I., . . . Robst, J. (2004).

Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC model.Health Care

Financing and Review, 25, 119-141.

Russo, C. A., VanLandegem, K., Davis, P. H., & Elixhauser, A. (2006).Hospital and ambula-

tory surgery care for womens cancers(AHRQ Publication No. 06-0038). Washington, DC:

Government Printing Office.

Shactman, D. (2005). Specialty hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, and general hospitals:Charting a wise public policy course.Health Affairs, 24, 868-873.

Sloss, E. M., Fung, C., Wynn, B., Ashwood, J. S., & Stoto, M. A. (2006). Further analyses of

Medicare procedures provided in multiple ambulatory settings(Prepared for the Medicare

Payment Advisory Commission). Retrieved from http://www.medpac.gov/publications/

contractor_reports/OCT06_Multiple_Ambulatory_CONTRACTOR.pdf

Stavrakis, A., Ituarte, P., Ko, C., & Yeh, M. (2007). Surgeon volume as a predictor of outcomes

in inpatient and outpatient endocrine surgery. Surgery, 142, 887-899.

Strope, S. A., Daignault, S., Hollingsworth, J. M., Ye, Z., Wei, J. T., & Hollenbeck, B. K.

(2009). Physician ownership of ambulatory surgery centers and practice patterns for uro-logical surgery.Medical Care, 47, 403-410.

by guest on April 20, 2014mcr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/http://mcr.sagepub.com/ -

8/10/2019 Med Care Res Rev 2012 Meyerhoefer 62 82

22/22

82 Medical Care Research and Review69(1)

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2006). Payment for ambulatory surgical centers

should be based on the hospital outpatient payment system(Publication No. GAO-07-86).

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

U.S. National Center for Health Statistics. (2006). The international classification of diseases, clini-cal modification, ninth revision. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Winter, A. (2003). Comparing the mix of patients in various outpatient surgery settings.Health

Affairs, 22(6), 68-75.

Yu, W., Revalo, A., & Wagner, T. (2003). Prevalence and costs of chronic conditions in the VA

health care system.Medical Care Research and Review, 60, 146S-167S.