McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

-

Upload

jobbeduval -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

1/16

0016-7398/05/0002-0001/$00.20/0 2005 The Royal Geographical Society

The Geographical Journal, Vol. 171, No. 2, June 2005, pp. 223238

BlackwellPublishing,Ltd.

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

WILLIAM J MCCONNELL AND SEAN P SWEENEY

Center for the Study of Institutions, Population, and Environmental Change, Indiana University, 408 North

Indiana Avenue, Bloomington, IN 47408-3799, USA

E-mail: [email protected]

This paper was accepted for publication in July 2004

There has been a huge surge in interest in the preservation of Madagascars forests in thepast two decades, but despite the investment of hundreds of millions of dollars, the goalremains elusive. Recent legislation has given the government the authority to enter intocontractual arrangements with communities for the management of the countrys public

forests, so it has become crucial to grapple with the significant challenges involved. Thispaper explores the enormity of the challenge of forest governance in Madagascar in anera of decentralization. By examining several forests in one part of the country, it revealsa dizzying range of forest types and forms of use and governance within a fairly smallportion of the country. These examples make it apparent that the history of forest manage-ment in Madagascar constitutes a broad-ranging experiment with forest governance.Simply monitoring the dynamics of the forest canopy is a significant technical challenge.However, this pales in comparison to the difficulties inherent in explaining those dynamicsand assessing the sustainability and equity of different management regimes. Of the forestsconsidered in the study, those where the Malagasy state has partnered with internationalconservation and development organizations seem to stand out, both in terms ofstabilized, or even growing, forest cover, as well as a balance of interests among users.

KEY WORDS:

Madagascar, forests, remote sensing, biodiversity conservation, institutions,decentralization

Introduction

M

adagascar hosts large and unique forestresources, and attempts to protect themfrom conversion to agriculture date back

at least two centuries, with a huge surge in interestin the past two decades. From the early nineteenthcentury, the islands forests have been claimed bythe state first by the Merina Monarchy, then by thecolonial French regime, and finally by the inde-pendent Malagasy Republics. In the early 1990s,the international biodiversity conservation communityentered the scene, leading the country to be thefirst in Africa to develop a National EnvironmentalAction Plan, largely centred on the preservation ofbiological diversity (Larson 1994; Kull 1996). Thetask has never been simple, however, and despitethe investment of hundreds of millions of dollars,the goal of conserving the countrys forests remainselusive. Along with preservation of remaining naturalforests, significant effort has been expended on

supplying timber and other forest products throughplantations. The legacy of French colonial initiativeshas important implications in this regard, as exoticplantations are found throughout the country, andmany are under the direct control of Malagasy state.

Through the last decade of international inter-vention, the traditional approach to conservation the creation of parks (fences and guards) hasbeen tempered with calls for a community-basedapproach, mirroring the emergence of decentraliza-tion of natural resource management in otherdeveloping countries. In Madagascar, recent legis-lation (GELOSE) has given the government theauthority to enter into contractual arrangementswith communities for the management of thecountrys public forests, but the success of this newapproach will depend on how well the governmentand its partners handle the significant challengesinvolved (Marcus and Kull 1999; Buck et al. 2001).

This paper explores the enormity of the challengeof forest governance in Madagascar in an era of

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

2/16

224

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

decentralization. The examination of several forests(Figure 1) reveals a dizzying range of forest types,as well as forms of use and governance, within afairly small portion of the country. At the sametime, our research highlights the difficulties ofmonitoring and explaining the dynamics of the

countrys forest resources. The paper begins with abrief review of recent theoretical developments inthe analysis of institutions and common-poolresources, and their importance in the search forworkable forms of forest governance in Madagas-car. The paper then undertakes a comparativeanalysis of six forests in the east-central part of theisland, presenting their environmental settings, theirfloristic and structural composition, and their useand management regimes. A time series of satelliteimages is then used to compare the forestdynamics over the past quarter century. These sixexamples show that the history of forest manage-

ment in Madagascar constitutes a broad-ranging

experiment with forest governance, providinglessons for future efforts.

Forest resources and institutions

Forest resources are often the sites of negotiationand contestation in large part because they poten-tially provide a broad range of ecosystem goodsand services, and priorities of the various stake-holders in a forest can differ widely. Priorities caninclude obtaining goods and services that requiremaintaining the forest and others that involveconverting or modifying certain aspects of theforest (Bishop and Landell-Mills 2002; Brown andRosendo 2000). For example, harvesting trees fortimber products is often, but not always, linked tothe conversion of land from forest to other uses,

especially agricultural production. Examples of goodsand services that accrue from avoiding modifica-tion or conversion of the resource include mainten-ance of hydrological functions (e.g. watershedprotection) or biological resources (e.g. geneticdiversity, carbon sequestration). Like all govern-ments, the Malagasy state must balance the variousinterests of its citizens and the internationalcommunity, each of which places different valueson various ecosystem goods and services. On onehand, the high rate of endemism of the islandsflora and fauna attracts the biodiversity conservationcommunitys interest in maintenance, and consid-

erable pressure has been brought to bear on, andsupport provided to, the government to conserve theforests intact. On the other hand, the huge majorityof the islands population derives its livelihooddirectly from the land, and thus closing the forestfrontier has serious implications for well-being.

Over the past decade there has been a strongpush to accomplish forest conservation in Madagascar,as elsewhere, through the formal decentralizationof forest resource governance. The growing experi-ence in actually implementing decentralizationthroughout Africa, however, has begun to reveal somereal difficulties. A main critique of such programs

charges that they reify monolithic communities towhich authority can be rapidly devolved, when infact these local communities are difficult todefine, much less successfully engage in conserva-tion activities, especially after a long era of strongstate control (Agrawal and Ribot 1999; Gibson etal. 2000; see also Twyman 2000; Brown 2002). Atthe same time, all forests are not alike, suggestingthat different approaches may be required in differ-ent places, taking into account the nature of theforests, as well as the characteristics of the varioususer groups and the products and services soughtby each. This realization lies at the heart of much

of the research conducted by scholars in the

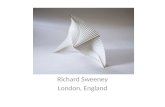

Figure 1 The study sites in MadagascarSource: Inventaire ecologique forestier national (DEF 1996)

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

3/16

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

225

Workshop of Political Theory and Policy Analysisat Indiana University, and has led to the develop-ment of the Institutional Analysis andDevelopment framework to examine how institu-

tions the formal rules and rules-in-use affecthuman incentives and behavior (McGinnis 1999).

At the core of the . . . approach are individuals who

hold different positions (e.g., member of a forest user

group, forest official, local forest user group official,

landowner, elected local, regional and/or national

official) who must decide upon actions (e.g., what

to plant, protect, harvest, monitor, or sanction) that

cumulatively affect outcomes in the world (e.g., a

forest ecosystem and the distribution of forest benefits

and costs).

Gibson et al.

2000, 9

Carrying this perspective specifically into thedomain of forest resources, the InternationalForestry Resources and Institutions (IFRI) researchprogramme focuses on the institutional rules-in-useshaping the use of forests. IFRI CollaboratingResearch Centers collect data on forests around theworld according to standardized protocols in orderto enable comparative analysis (Gibson et al.

2000;Ostrom and Wertime 2000). The study describedin this paper draws upon and contributes to theseanalytical perspectives.

The forests: location and composition

According to Madagascars most recent and author-itative land-cover assessment, the InventaireEcologique Forestier National, forests covered almosta quarter of the island in the early 1990s (DEF 1996).Of these 13 000 000 ha of forest, a considerableportion is found within the countrys hundreds ofparks, reserves, and other lands directly under thestates control; just over 1 000 000 ha are inplantations (Table 1). Based solely on the size ofthe resource, it is clear that the management taskis huge, but when the communities using the

resource are considered, the challenge is moredaunting still. The countrys population of morethan 12 million, comprising some 13 000 commu-nities, is mainly concentrated in the more humidareas where most of the forests are also found(Green and Sussman 1990; Bertrand 1999). Forestresources play a vital role in the countrys economy,through the provision of a range of goods andservices. Fuel wood remains an important source ofenergy in urban areas and is the sole source ofcooking and heating for the majority of the ruralpopulation. In addition to providing a number ofother products and services, forest land is the main

source of new agricultural land. Thus, many rural

livelihoods are directly dependent on forest resources.Meanwhile, tourism is the countrys most importantsource of foreign exchange, and most of this istargeted in forest areas.

In order to illuminate the diversity of forest typesand management regimes currently in place, thisstudy considers six forests in the east-central partof the country, presenting information collected ininitial surveys carried out in 1998 and 1999 and

follow-up visits in 2001. Initial data collectionproceeded according to the IFRI protocols, includ-ing standard forms for the collection of informationon forests and the communities that use them(Rakotozafy et al. 2002). Part of this data collectioninvolved the derivation of sketch maps showing theland management units within each forest understudy. The follow-up visits served mainly to collecttraining samples information used in the inter-pretation of satellite images to monitor changes inforest resources over time (described later). Bothinitial surveys and follow-up visits included basicforest mensuration (e.g. key arboreal species,

height of canopy and emergent trees, tree diameter,etc.), as well as individual and group interviewswith forest users.

Finally, satellite images acquired in 1985, 1994,and 2000 were analysed, along with land-coverinformation extracted from topographic maps,which are based on aerial photographs from 1957(McConnell et al. 2004), in order to assess land-cover change in the forests. It should be noted thatthe information on forest dynamics presented hereis limited by the spatial and spectral propertiesof the satellite images relative to the complexity ofthe landscapes in question, and by the brevity of

the fieldwork undertaken. The analysis relied

Table 1 Madagascar forest resources

Extent of island 58 700 000 ha

Extent of forest 13 260 000 ha

State forest types No. Area (ha)

National parks 5 175 361

Special reserves 23 371 393

Integral natural reserves 11 569 542

Classified forests

and forest reserves

259 4 023 446

Forest stations 23 57 294

Hunting reserves 4 n/a

Reforestation and

restoration areas

101 1 044 895

Total 426 6 241 931

Source: DEF (1996)

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

4/16

226

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

primarily on Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM) andEnhanced Thematic Mapper (ETM+) images, whichcontain information on the Earths surface in pixelswith a nominal spatial resolution of 30 m. At

this resolution, the smallest forest unit analysedis represented by approximately 5000 pixels, ofwhich a significant proportion are along the edge,where change and confusion in classification are most likely to occur.

The results of the discrete classification process,in which the spectral data were converted intoland-cover classes (in this case, binary forest-covermaps), should not be accorded undue certitude.While the TM and ETM+ sensors are designed inlarge part to discriminate between vegetation types,the spectral signatures the information recordedby the satellite across six windows of the electro-

magnetic spectrum of broken-canopy mature forestare quite similar to those of advanced successionalforests, and both of these are similar to variousstages of coppice regrowth (Mausel et al. 1993;Nelson and Horning 1993). In addition, it is difficultto assess the impact of seasonality. The differencesin the acquisition dates, March 1985 and Decem-ber 1994, of the scenes covering the highland sitescould result in some confusion between successionand seasonal greening. Inconsistencies in classcomposition can potentially produce exaggeratedland-cover change results. Every attempt was madeto minimize the impact of seasonality by employ-

ing all available training data.Classification training data were derived from43 in situ training samples, dozens of field photos,as well as field notes, including land-use histories.Spectral signatures derived from training data wereplotted over a band 3/band 4 scatterplot for eachimage and class signatures generated from areas ofinterest (AOIs) that delineated class clusters, usingERDAS Imagine. Pixels located within the AOIswere classified by the non-parametric decision ruleof Feature Space. Pixels falling into the overlapregion of two or more AOIs, or outside of all AOIs,were classified by a parametric decision rule based

on the probability of a pixel belonging to a givenclass, using the maximum likelihood algorithm.The classes were subsequently collapsed, and amajority filter, using a 3 3 moving window, wasapplied. Once the images were classified intoforest/non-forest maps, they were overlaid to yieldforest-cover change maps and statistical summaries.

The forests analysed here included a very broadrange of forest types, situated within a relativelynarrow range of environmental conditions. Thisvariation in forest types is important in understand-ing the range of resources that are in play in forestgovernance. While the sample is quite varied, it

represented a small subset of the overall variation

in forest types and environmental settings found inMadagascar. All of the forests considered herewere located in the mountainous terrain ofMadagascars central highlands and eastern escarp-

ment, with a maximum elevation ranging fromabout 1000 to 2000 m above mean sea level. Theaverage annual temperature ranges from 13 to24 C, while precipitation ranges from 1200 to almost2200 mm per year. The forests were all within afew hours drive from the capital Antananarivo(20165 km), and within 15 km of the nearestadministrative centre.

The forests varied considerably in size, althoughit is important to note that determining the size of aforest management unit can be difficult. In theabsence of reliable, current cadastral maps, bound-aries on sketch-based maps, such as those

completed as part of IFRIs Site Overview Form,may be the best approximation. At the same time,the management definition of a forest often willexceed in size the boundaries of a forest definedby morphological or floristic criteria. In othercases, a management unit may be just a portion ofa larger forested area. In the simplest cases consid-ered here, the 450 ha Tsiakarana forest and the900 ha Manjakatompo forest, both in the interior ofthe central plateau, had quite distinct boundaries,as they were completely surrounded by agriculturallands. Two other forests consisted of portions of thelong, thin forested area marking the eastern edge of

the islands central highlands at the upper edge ofthe escarpment. These include the 800 ha Beoranaforest and the nearly 4000 ha Durand Devillaineforest. The remaining two forests likewise consti-tuted portions of a much larger forest mass, inthis case in the mountains between the centralhighlands and the east coast: the Vohidrazana andMaromizaha forests were contiguous portions of aforest mass of over 30 000 ha to the south of RouteNationale 2, which breaks the corridor as it runsfrom the capital to the coast (the 10 000 ha Manta-dia National Park forest lies to the north of thehighway).

The forests also varied in terms of floristic andstructural composition, ranging from relativelypristine, natural forest to homogeneous planta-tions of exotic species, with various mixtures ofthese types in between. At the natural end of thespectrum, the Vohidrazana forest was a largelyintact cloud/rain forest containing a wide range ofindigenous flora and fauna bordered by agriculturallands. At the other end of the spectrum, the Tsiaka-rana forest consisted mainly of two species of pine(Pinus patula and P. khesia) in stands of variousages, resulting from a checkerboard clear-cuttingreplanting management scheme. There was also a

stand of mature eucalypts (Eucalyptus spp.) within

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

5/16

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

227

the Tsiakarana forest, and the adjacent grassy hillswere being planted in eucalyptus as well. Theremaining forests in this study were hybrids,containing plantations of exotic trees, including

pine, eucalyptus, mimosa (Acacia spp.), andquinine (Cinchona spp.) stands within or adjacentto natural forest. The Manjakatompo forest was aninteresting outlier in this respect, as the naturalportion of the forest was composed of an unusuallynarrow set of indigenous species.

Forest use and management

It should not be surprising that these diverse foresttypes, existing in different ecological settings, weresubject to quite different use and managementregimes. In the classic formulation of forest conser-

vation, the Malagasy state is concerned withrestricting access of farming communities to thenatural forests. Farmers would traditionally cut andburn this forest to prepare it for planting of hillrice. Known in the Malagasy language as tavy, thissystem has long been employed throughout theworld for the itinerant production of rain-fed cropssuch as rice (Conklin 1954; Jarosz 1993; Messerli2000; Laney 2002). The Malagasy brought thispractice with them when they migrated fromKalimantan some 1200 years ago (Dahl 1991). Thesustainability of the system depends on the avail-ability of sufficient land, such that after one or two

years of cultivation the plots may be left in fallowlong enough for the forest to re-establish itself.Land pressure eventually requires farmers to re-useland more frequently, and natural succession iscurtailed. The states intervention, closelysupported by international donors and conservationgroups, is intended to interrupt this cycle andprotect remaining forest from such conversion.

This classic case was closely approximated in theVohidrazana forest. As described earlier, the Malagasystate has long asserted control over forests that farmingcommunities consider their ancestral domains. Thus,devolution of forest governance would constitute a

return of some measure of control over the resourceto those communities. In practice, it is extremelydifficult to exclude neighbouring populations fromaccess to the many resources of the forest. InMadagascar, as in many other parts of the world,national and international agencies have attemptedto halt, or at least slow, forest conversion throughthe promotion of intensive, permanent agriculture a process fraught with difficulties (Keck et al. 1994;Messerli 2000; McConnell 2001).

Other forests under state control differed substan-tially from this classic formulation. The Tsiakaranaplantation, on the outskirts of the capital city, was

created by the planting of exotic tree species on

hilltop grasslands. The management goals werethose of industrial forestry maximum sustain-able yield while minimizing management costs.Meanwhile, the presence of large plantations of

exotic trees alongside the natural forests atBeorana, Durand, and Manjakatompo led tohybrid management schemes, encompassing bothconservation and production goals.

The following sections consider the products andservices derived from each of the forests, the usergroups, and the rules governing users access tothose products and services.

Attributes of the resource

Information collected on the IFRI forest and forestproduct forms reveals that the products garnered

from the six forests included both timber and woodproducts as well as a range of non-timber forestproducts, and services including tourism andreligious observance. Vohidrazana (a natural forest)and Tsiakarana (a plantation) provided relativelyrestricted sets of products and services, while theuses of the hybrid forests were quite varied.

In terms of traditional forest products, all of theforests in this study were subject to some harvest-ing of timber for construction materials and fuelwood, although at very different intensities. TheTsiakarana plantation was the most intensivelyharvested for timber, while fuel wood extraction

was decidedly more prevalent in the natural Vohid-razana forest. In addition to these products, thehybrid forests Beorana, Durand, and Manja-katompo also hosted charcoaling activities fromboth their natural and artificial (exotic) stands.

Non-timber forest products collected from theforests included honey, leaves, bark, crayfish,minerals (construction materials and semi-preciousstones), and livestock browse. Many of these werelikely under-reported in the survey data, but thereappeared to be little pattern to their extractionacross forest types, other than their near completeabsence in the Tsiakarana plantation. Tourism

appeared to offer potentially lucrative returns inthose natural forests well situated and developedto accommodate visitors, including the Manja-katompo and Maromizaha forests, although tourismin Madagascar still required heavy subsidies. Thelevel of provision of religious services was moredifficult to assess. While the Manjakatompohosted large numbers of pilgrims in its sacred sites,sacred groves were found within and adjacent tomany other forests. In a broader sense, all naturalforests are considered by rural society to have acertain sacred value, often with attendant ritualsobserved before entrance into and exploitation of

the forest.

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

6/16

228

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

All forests included here were located within oradjacent to agricultural landscapes, and it can beargued that conversion of forest to agricultural useswas an important service demanded of the forest

land. In those instances where the boundary of theforest was formally demarcated, and inside ofwhich farming was taking place, the demand forconversion was clearly seen.

Attributes of the users

As described above, the number of products andservices derived from the purely natural and purelyexotic forests were restricted compared with thebroader range extracted from the hybrid forests.Information collected on various IFRI formsconcerning the users of the resource showed that

the number and characteristics of the user groupsmirrored this pattern. With the exception of theprivately owned Durand, all of the forests wereunder the formal jurisdiction of the Malagasy agencyresponsible for forest management, the Ministry ofWaters and Forests (Ministere des Eaux et Forets, orMEF, which has since merged with the Ministry ofthe Environment).

In the classic case, the main dynamic in forestgovernance is between the legal owners of theforest (public or private) and neighbouring farmingcommunities whose members wish to extractproducts and services from the forest (or convert

the forest to agricultural land). Again, the naturalforest of Vohidrazana best typified this dynamic;although there were other actors involved inexploiting the forests (including clandestine timberharvesters), the farming communities were the onlyorganized and recognized user groups. It would bea mistake, however, to characterize the dozens offarming communities surrounding this, or any other,forest as internally homogeneous. Wide disparitieshave been noted both among and within suchcommunities in terms of the levels of social differ-entiation and cohesion, as well as access to anddependence on forest products and services (Ribot

1995; Laney 2002). Nevertheless, with respect tothe other forests covered in this analysis, the numberand diversity of the user groups in the Vohidrazanaforest and Tsiakarana plantation were quite limited.In the latter, the private, for-profit timber companySahy enjoyed a contractual relationship with theMEF for the harvesting of timber. Meanwhile,neighbouring communities enjoyed the right toglean fuel wood following harvesting.

In those forests where other uses were possibleor permitted, more user groups were involved inexploiting those resources. For example, whentourism was a viable commodity, such as in the

Maromizaha and Manjakatompo forests, tourists

constituted a significant user group, as did the guides,who in both cases belonged to formal organiza-tions. In those publicly owned forests that includedsignificant plantation stands (Beorona and Manja-

katompo), user groups had formed around timberharvesting and/or charcoal production. In addition,user groups had formed for the exploitation of avariety of other goods and services, including thegathering of non-timber forest products for medicinalor small-scale consumptive, artisinal, or commercialpurposes, as well as religious observance.

Management regimes

The six forests represented quite an array of approachesto forest management, including private ownershipbacked by the authority of the state and state

ownership with varying levels of both co-managementand outside assistance. In terms of both products andservices and the groups involved in their exploit-ation, discussed earlier, the Vohidrazana forest andthe Tsiakarana plantation were found to exhibitrelatively restricted ranges of conditions, while thehybrid forests were much more complex. Thus, onemight expect the management regimes to be morecomplex in the hybrid forests, and this is indeedthe case.

Clearing of forest land for agriculture (tavy) inthe Vohidrazana and Maromizaha forests wasregulated by a traditional system of lineage tenure,

overlaid by a formal system requiring a permit fromthe forest service. In each community, clan patri-archs (tangalamenas) granted rights to create tavy,and ideally a permit was obtained from the MEF.Prior analyses of satellite images demonstrate thatrapid conversion of forest to agricultural land overthe past quarter century abated in the past decade,although signs of clandestine agricultural conver-sion deep in the forest interior were detected(Schoonmaker-Freudenberger 1995; McConnell etal. 2004). Restrictions on the harvesting of fuelwood (limited to deadwood) appeared to be largelyrespected, but during the field visit to the Vohidra-

zana forest, lumber extraction was observed,reportedly an illicit use involving a local municipalofficial. A similar situation prevailed in the naturalportion of the Maromizaha forest, although hereillicit use involved the production of charcoalrather than lumber.

There had been a significant level of outsideintervention in this region over the past decade,including Swiss and American-funded projects,particularly in the Maromizaha forest, with itselevation to the status of a buffer within the MantadiaAnalamazaotra Protected Areas Complex (APAM).The possibility for tourism in the buffer zone added

another layer of complexity to the governance of

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

7/16

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

229

forest resources at the site, and several residentswere members of APAMs tourist guide association,Isavalalana/Association des Guides dAndasibe. Inprinciple, the village of Anevoka would have

participated in the APAM Integrated Conservationand Development Project, which was to involverepresentatives from surrounding communities indecisions about the management of the protectedareas (including the use of tourist revenues) (Fordand McConnell 2001). The residents of Anevoka,however, reported no involvement in the making offormal rules for the use of forest resources.

Residents were, however, actively experimentingwith the management of exotic plantations in thisarea, including generations-old eucalyptus timberstands, and the development of a riceeucalyptusrotation wherein rain-fed rice was planted follow-

ing eucalyptus coppicing, taking advantage of themuch maligned sterilizing properties of theeucalyptus litter to repel rice pests. These develop-ments were striking given that there was barelymore than one generations experience with treemanagement.

Unlike the harvesting in Vohidrazana and thehybrid forests, harvesting of both timber and fuelwood in Tsiakarana appeared to largely conform toformal rules, with the notable exception of thetapping of pine resin to make fire-starters for salein Antananarivo. The Tsiakarana pine plantationwas begun in the late 1960s under the youth

employment initiative Zatovo Ory Asa Malagasy toprovide pulp for a paper factory. A fire almostcompletely destroyed the plantation during aperiod of widespread social unrest throughout thecountry in 1974. By 1987, the plantation had suffi-ciently regenerated that it required pruning, andlocal residents were allowed to harvest firewoodunder a tacit arrangement with the field forester.

In 1996 MEFs Direction Interregional in Antan-anarivo began undertaking contractual arrangementswith private logging firms, for example, the SahyCompany, under a formal management plan. Thesurrounding communities benefited from this manage-

ment regime both through wage labour and throughthe right to glean logging by-products and dead wood(during the wet season) for domestic consumption.The right to glean fuel wood from logging slashwas codified in a 1996 Order by the Commune ofMasindray, establishing a formal relationshipbetween the local population and the MEF, whilethe right to remove dead wood remained informal.

Strong demand for fuel from the nearby capitalmade monitoring of illegal consumption in this forestquite difficult. The extraction of resin to make firestarters was particularly problematic, as it results inthe mutilation of the pine bark. In response, the

MEF sought to increase the degree of community

participation, including the labour-intensivemonitoring and expansion of the plantation. Theseefforts were being implemented through fokontany-level committees for the forest and the environment

(Komitinny Ala sy ny Tontolo Ianinana), whotypically work on a voluntary basis (the fokontanyis an administrative sub-division of the commune).Among the seven fokontanyin the vicinity, those tothe south were actively participating, while thoseto the north, who had reportedly turned a blindeye (at least) to the resin tapping, were less enthu-siastic. This reticence may be related to lingeringresentment over the communities limited manage-ment role in the forest, despite having provided thelabour for its establishment and monitoring, and tothe replacement of their pruning with contractuallogging, in whose profits they did not share.

One of the more problematic cases in terms ofmanagement is the Beorana quinine plantation andits adjoining natural forest. Here, the MEFs limitedability to monitor formal rules has led to a tacitdevolution to former plantation workers since thelate 1980s. The result was an open-access situa-tion, with plantation workers competing withresidents of surrounding communities. Localcommunities in and around Beorana, despitehaving no formal responsibility for forest manage-ment, have nevertheless been held responsible fordamage caused by fire. Unlike Tsiakarana,however, no formal arrangement had been made

either with private-sector firms or local commu-nities, and there was evidence that authorities hadbeen bribed to avoid fines for illegal charcoalproduction. By the summer of 2001, privateindividuals from the capital were seeking formaltitle to lands within the forest and had begunconstructing residences and fences.

Perhaps even more problematic is the privatelyowned Durand forest. Originally claimed by aFrench colonist, the forest was ceded to one of hisMalagasy employees following independence in1963, and finally inherited by a set of siblings.While the Ramaherison family consisted of some

69 households, the 13 direct heirs owned the landand sold forest resources. These activities werecoordinated with MEFs regional and local offices,as well as with the commune of Ambatolaona.

Residents of surrounding communities hadnegotiated informal arrangements with individualfamily members concerning the harvesting of forestresources, often resembling share-cropping. In addition,some residents have contested the familys claim toa portion of the forest through the courts. Theconflict has led to the levying of fines against localresidents, and even to their confinement in jail.

The Manjakatompo forest is an interesting case.

Tradition holds that the forest was moved to its

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

8/16

230

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

current location several generations ago in order tosecure an alliance between a group in this area,which then had no substantial forest cover, andanother group living at the forest edge on the

escarpment 50 km away. Reportedly, seeds fromthe forest were ingested by members of the moredistant community, carried in the intestinal tracts,and subsequently deposited at the site.

Since 1996, Manjakatompo has been managedunder a formal contractual arrangement betweenthe MEF and an association representing users inthree communes in the fivondronampokontany (ahigher-level administrative unit) of Ambatolampy.The Union Forestiere dAmbatolampy (UFA) isgoverned by a six-member executive committeeconsisting of representatives of the two neighbouringvillages forest maintenance groups (Vondronny

Mponina Mpanazary ny Ala, or VMMA). The manage-

ment plan for the forest, agreed at an annualgeneral membership meeting, was purposely complex.Neighbouring residents were accorded rights topasture animals and to collect household firewood

and medicinal plants. The UFA authorizedcommercial logging by the VMMAs and sanctionedtour guides for national and international visitors;both involved local labour. Meanwhile, the use ofthe forest for religious purposes was coordinated bya group of traditional doctors (zandrano), consist-ing of about two dozen households who havereportedly been organized since 1560. Very littleillegal exploitation of timber or fuel wood hadtaken place in the Manjakatompo forest. The successof this arrangement cannot be divorced from theintegrated forest development project (Projet deDeveloppement Forestiere Integr du Vakinankaratra)

of the German development agency GTZ.

Figure 2 Maromizaha and Vohidrazana forests, 195720001

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

9/16

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

231

Forest dynamics

Satellite images provide a view of the trajectory of

a forests canopy, and while much goes on beneaththe canopy that cannot be seen, this synoptic viewof the overall stand dynamics is important inassessing forest management. This section reviewsthe results of change detection carried out usingthe satellite images described above.

The six forests showed considerable variation inthe level of stand dynamics, measured in terms ofboth overall (net) change in forest extent and inter-nal dynamics of clearing and replacement, withinwhat are called here land management units(LMUs). The latter dynamics resulted from both thereplacement of natural forests with exotic planta-

tions and cyclic coppicing (lopping and sprouting)and harvest-replanting within established planta-tions, as well as from clearing for agriculture andsubsequent fallowing or abandonment and forestsuccession. Vohidrazana forest and Tsiakaranaplantation are very active in terms of net change,and display clear trends.

The Vohidrazana and Maromizaha forests under-went significant contraction over the past halfcentury, with more than a quarter of the forested areacleared for agriculture between 1957 and 2000(Figure 2). However, these rates dramatically levelledoff in the 1990s (McConnell et al. 2004). While there

are some plantations on the outskirts of the forests,

fieldwork indicated that these had been largelyquite stable. For example, the mature eucalyptusgrove in Ambalavero was established decades ago

and provides lumber for home construction. Theeucalyptus stands in the Maromizaha forest aroundAnevoka are coppiced at a younger age forcharcoaling.

In contrast, the Tsiakarana pine plantationexpanded by more than 30% between 1976 and2000, recovering from the fire in 1974 (Figure 3).The stands within the Tsiakarana plantation areharvested in a regular rotation, with regularlyspaced individual trees left standing to providenatural reseeding. Thus, the dynamics of the twoextreme cases are quite clear: expansion of theplantation accompanied by high internal dynamics

and attenuated contraction of the natural forestwith a very quiet core.

Not surprisingly, the hybrid forests present amore ambiguous picture, with moderate overalldynamics. Partitioning change among the naturaland plantation components of the hybrid forestsfrom satellite images is quite challenging forseveral reasons, in addition to the difficulties ofdelineating forests discussed earlier. The spectralsignatures of eucalyptus, mimosa, and quinine areparticularly difficult to distinguish from one anotherand from those of natural forests, especially inrough terrain, where topographic shadowing is

severe. In addition, while a cartographically accurate

Figure 3 Tsiakarana forest, 198520002

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

10/16

232

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

base map of the Manjakatompo site enabled reliablediscrimination of dynamics in different portions ofthe forest, georeferencing of the sketch maps ofthe Beorana and Durand forests was difficult, andthe results presented here should be treated withsome caution. Nevertheless, some qualified obser-vations can be made.

The majority of deforestation between 1985 and1994 in and around the Beorana site (Figure 4)occurred outside the portion of the forest con-

sidered here, along the western and northern edges ofthe forest mass that is, southward and eastwardrecession of the forest edge. This recessional clear-ing appears to be associated with surroundingsettlements: the southwestward recession is adjacentto the village of Amboavahy; the southeastwardrecession is in proximity to the villages of Ambod-isaonjo and Ambero; and the westward recession isadjacent to the village of Ambosipotsy. Within thenatural forest LMU, the forest experienced a slightcontraction, mainly concentrated in the south andnortheast. The patches of deforestation in the southlie near a much larger forest area that reportedly

burned later (in 1995) near a hamlet of Ambosipotsy.

Other patches in the northeast are adjacent topreviously non-forested areas. A small amount ofnew growth was detected in the areas not underforest in 1985, with a resulting net loss of 4% ofthe initial forest cover in this LMU. The trendswithin Beoranas quinine plantations were similar:a net loss of just under 4%. In terms of spatialpatterns, land-cover dynamics in both of BeoranasLMUs were concentrated around the forest edgesand in close proximity to roads and paths.

A great deal of deforestation also occurred outsidethe Durand forest boundaries between 1985 and1994 (Figure 5), particularly to the east and northeast.Within Durands natural forest LMU, considerableclearing took place, mainly near the northeasterncorner, with patchy clearing in the northwest at ornear the edge of non-forested areas. This was morethan offset by afforestation, resulting in a net gainof almost 2% of the LMU. The length of the periodobscures highly dynamic coppicing known to existin the acacia and eucalyptus plantations, but majorafforestation, particularly acacia, resulted in asignificant net gain of 14%. Unlike in Beorana,

there is no clear spatial pattern of deforestation and

Figure 4 Beorana forest, 198519943

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

11/16

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

233

regeneration in either of Durands LMUs, but rathera patchwork of change.

Cloud cover limited the analysis of land cover inManjakatompo between 1985 and 1994 to the

eastern third of the forest (Figure 6(a)), but earlier(1976) and later (2000) images indicate that theeastern area has been the most dynamic part of theforest. The natural forest LMU experienced a netloss of almost 10%. Areas of conversion werelargely concentrated in the two large blocks offorest in the northeast, with some of the cuttingreaching far into the interior of the forests. Duringthis period, a great deal of activity was seen in theplantation LMU, with huge clearing in the north-east portion and new growth in the central andsouthern portions, resulting in a net loss of over 9%.

The availability of cloud-free images in this

region permitted the analysis of dynamics in a

second, shorter period, from 1994 to 2000 (Figure6(b)). By 2000, the Manjakatompo forest had madea remarkable recovery from its decline in the previ-ous period. In the natural forest LMU, the clearing

afforestation relationship almost perfectly reversed,leading to an 11% increase in forest cover. Thesituation in the plantation LMU was equallydramatic, where forest cover grew by almost 13%.Note that the second period covers just six years,compared with nine years between the earlierdates. In both LMUs, forest was usually cleared inlarge, continuous blocks, giving the appearance ofsystematic and localized use.

Comparing these three hybrid cases (Figure 7),the small, remote Beorana forest was the quietestfrom 1985 to 1994. During a period of nearlycomplete state neglect, it suffered minor contrac-

tion in forest cover in both the natural and

Figure 5 Durand Devillaine forest, 198519944

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

12/16

234

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

Figure 6 Eastern Manjakatompo forest: (a) 19851994; (b) 199420005

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

13/16

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

235

plantation LMUs, with less than 10% of these areasundergoing either deforestation or afforestation.The Durand forest, five times the size of Beorana,was much more dynamic, even when taking itssize into account. In the midst of hotly contestedrights, 10% of the natural forest LMU underwent

change, while a fifth of the plantation LMU was inplay, mostly accounted for by shifts from non-forest to forest. Meanwhile, the three dates ofimages available for the Manjakatompo site tell aCinderella story. In the earlier period (198594)both LMUs were quite active. Change was detectedin about 18% of the natural forest LMU and 40%of the plantations, resulting in significant contrac-tion of forest cover in both cases. Overall dynamicsin the later (shorter) period, during which the GTZ-supported contractual arrangement between MEFand UFA began, were relatively muted, but the neteffects were completely reversed, with major

expansion in forest cover in both LMUs.

One might expect the plantations to be the leastcomplicated in terms of forest dynamics, productsand services, user groups, and management regimes,and this appears to be the case. However, the

natural forests are also relatively simple. The mostcomplex and dynamic forests are the hybrid forests,where people have been planting trees, exploitingother resources, and forming groups in addition tothe traditional community. This is where the MEFhas the richest experience in interacting with arange of groups with varying interests, influenceand skills, and this is an important testing groundfor approaches to forest governance.

Discussion

The success of a forest governance regime may be

judged along both biophysical and social dimen-sions. Biophysical management goals may rangefrom preserving biodiversity by maintaining asmuch natural forest intact as possible, to themaximization of either woody biomass in place(i.e. for carbon sequestration) or biomass harvesting(e.g. timber, pulp). Social goals may range from themaximization of total revenue (be it from tourism,or from the production of timber or otherproducts), to the provision of services, whilst ensur-ing sustainability and equity in the enjoyment ofsuch benefits may be a major consideration.

The traditional approach followed by various

governments in Madagascar has been for the stateto assert sole ownership and to attempt direct,centralized management of the countrys forests.This approach is limited by the sheer physicalextent of the resource, and the large number ofusers seeking products and services therein, whichtogether prohibit effective monitoring by a centralauthority alone. It is not surprising, then, thatMalagasy governments, from the Merina monarchyonward, have relied on some more localizedauthorities to ensure compliance with their central-ized control, and have thus been engaged in someform of co-management for centuries. The evidence

from the six forests analysed here provides someindications of the results of pursuing different formsof co-management, as measured along the biophys-ical and social dimensions outlined above.

One approach to co-management is for the stateto support private ownership of forests. Thiscomparative analysis includes only a single suchcase, the Durand forest, but the evidence is notencouraging. While forest cover was found to haveexpanded, this was achieved in large measurethrough reforestation following the clearing ofnatural forest, with consequent negative impacts onbiodiversity. From the standpoint of total production,

the management regime may have been quite

Figure 7 Comparison of forest dynamics in Beorana, Durand,and Manjakatompo

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

14/16

236

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

successful, but the continued contestation ofcommunity rights to access, marked by fines andimprisonment, was evidence of serious equityconcerns, and brings into question the sustain-

ability of the management regime.The problems encountered when the state exertscentral control without sufficient financialresources is well illustrated by the case of theBeorana forest. The physical dynamics at this sitehad largely been limited by its physical geographyand related infrastructure and settlement pattern.Thus the forest canopy had been relatively stable,but the overall trend detected was a net loss ofcover in both the natural and plantation areas. Interms of social dimensions, the effective neglecthad enabled surrounding communities to continuegaining access to agricultural lands, but punish-

ment of these communities for their perceivedresponsibility for forest fires attests to a dysfunc-tional relationship. The informal arrangement withformer plantation workers complicated the situa-tion, and is difficult to interpret as a constructiveexample of co-management. Private individualswere reportedly seeking title to land in the forest,and the experience in the Durand forest does notlend optimism for the success of this development.

The remaining forests Vohidrazana, Maromi-zaha, Tsiakarana, Manjakatompo are cases inwhich more concerted attempts had been made toengage local communities in managing state-

owned forest resources. The recent declines indeforestation rates in the Vohidrazana and Maromi-zaha natural forests were encouraging, as was thestability of their abutting plantations. The clandes-tine opening of clearings in the interior indicatedless-than-perfect community cohesion, but Swissand American conservation and developmentprojects were making strides in building strongrelationships as the foundation for more formalcollaboration between the communities and thestate. Agreements with communities neighbouringthe Tsiakarana pine plantation had been crafted,and while some resistance was evident, the

management of the forest appeared to be resultingin sustainable, and even expanding, timber produc-tion (the maintenance of biodiversity not being arelevant management goal). Communities werebenefiting from wage labour participation in thelocal logging industry and from access to domesticfuel wood. There was clearly room for improve-ment, in terms of limiting destructive resin tappingand achieving broader and deeper collaboration,but the experience permits some optimism.

From the evidence presented here, the Manja-katompo forest appears to present a valuable examplefor the crafting of multiple-use, multiple-user forest

management regimes. The canopy had begun

recovering from rapid decline, and the forest wasproviding a broad range of products and services tolocal residents, as well as to visitors from aroundthe country and from abroad. The management

plan was derived from a broadly collaborativeprocess, based on the formalized participation ofvillages and other groups. As such, it comes closestto what has been called adaptive collaborativemanagement (Buck et al. 2001).

Conclusions

The main conclusion to be drawn from the exam-ination of these six forests is that there exists inMadagascar a huge variety of forest types, uses,users, and management regimes. The forestspresented here comprise only 0.3% of the islands

total forest, and just 0.6% of the protected forests.Simply monitoring the dynamics of the forestcanopy is a significant technical challenge, anddespite considerable investment over the past halfcentury, there remain considerable uncertainties inthe actual quantities, locations, and rates of change(Nelson and Horning 1993; DEF 1996). Thechallenge of monitoring, however, pales incomparison to the difficulties inherent in explain-ing those dynamics and assessing the sustainabilityand equity of different management regimes(McConnell 2002).

If successful management of forest resources

were easy, it would be done by now. Clearly it isnot. But just saying it is difficult is not goodenough, and decentralization is no panacea.Shouting slogans about the desirability of decen-tralization or civil society contributes little towardthe crucially important task of sustaining capacitiesfor self-governance (McGinnis 1999, xii). Equitableand sustainable management of Madagascarsforest is most likely to result from careful, rigorousanalysis of the physical dynamics, and from aprocess of learning from the range of governancearrangements that have been tried in the past.Long-term commitments on the part of interna-

tional conservation and development agencies maywell prove decisive in this process.

Acknowledgements

The research reported here builds upon the founda-tions laid by our Malagasy colleagues, includingRoland Raharison, Vololoniana Rakotozafy andClaude Andriamalala, who conducted the initialfield work in 1998 and 1999 and participated inthe follow-up visits in 2001. The information theycollected and their unpublished reports weresources for floristic and morphological information,

as well as details on the products, services and

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

15/16

Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

237

user groups in the forests. Responsibility for anyerrors, omissions or misinterpretation of this infor-mation rests with the authors. The 2001 field visitsand satellite image analysis were made possible by

National Science Foundation grant SBR9521918 tothe Center for the Study of Institutions, Population,and Environmental Change at Indiana University.CIPEC colleagues Jon Unruh and Nathan Vogt par-ticipated in the 2001 field visit, and Joanna Broderickprovided assistance with the preparation of themanuscript; their assistance was invaluable.Finally, the careful reading and constructive com-ments of two anonymous reviewers are gratefullyacknowledged.

Notes

1

Source

: Topographic map name: Manjakatompo; scale:1:20 000; projection: Conformal Laborde; publisher:

Institut Geographique et Hydrographique National/Foiben-

TaosarintaninI Madagasikara [Madagascar]. Scene ID:

LE7158073000011050; platform: Landsat 7 Enhanced

Thematic Mapper; acquisition date: 19 April 2000; path: 158;

row: 073; cell size: 30 m; registration: 55 control points;

RMS error: 0.5692.

2

Source

: Scene ID: LT5159073008506710; platform: Landsat

5 Thematic Mapper; acquisition date: 8 March 1985; path:

159; row: 073; cell size: 30 m; registration: 35 control

points; RMS error: 0.5583. Scene ID: LE7159073000013350;

platform: Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper; acquisition

date: 12 May 2000; path: 159; row: 073; cell size: 30 m;registration: 26 control points; RMS error: 0.6727.

3

Source

: Scene ID: LT5159073008506710; platform: Landsat

5 Thematic Mapper; acquisition date: 8 March 1985; path:

159; row: 073; cell size: 30 m; registration: 35 control

points; RMS error: 0.5583. Scene ID: LT5159073009434810;

platform: Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper; acquisition date:

14 December 1994; path: 159; row: 073; cell size: 30 m;

registration: 32 control points; RMS error: 0.5443.

4

Source

: Scene ID: LT5159073008506710; platform: Landsat

5 Thematic Mapper; acquisition date: 8 March 1985; path:

159; row: 073; cell size: 30 m; registration: 35 control

points; RMS error: 0.5583. Scene ID: LT5159073009434810;

platform: Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper; acquisition date:14 December 1994; path: 159; row: 073; cell size: 30 m;

registration: 32 control points; RMS error: 0.5443.

5

Source

: Scene ID: LT5159073008506710; platform: Landsat

5 Thematic Mapper; acquisition date: 8 March 1985; path:

159; row: 073; cell size: 30 m; registration: 35 control

points; RMS error: 0.5583. Scene ID: LT5159073009434810;

platform: Landsat 5 Thematic Mapper; acquisition date:

14 December 1994; path: 159; row: 073; cell size: 30 m;

registration: 32 control points; RMS error: 0.5443. Scene ID:

LE7159073000013350; platform: Landsat 7 Enhanced

Thematic Mapper; acquisition date: 12 May 2000; path: 159;

row: 073; cell size: 30 m; registration: 26 control points;

RMS error: 0.6727.

References

Agrawal A and Ribot J

1999 Accountability in decentralization:

a framework with South Asian and West African cases Journal

of Developing Areas

33 473502

Bertrand A

1999 La gestion contractuelle, pluraliste et sub-

sidiaire des ressources renouvelables Madagascar (19941998)

African Studies Quarterly

3(2) art 6 (http://web.africa.ufl.edu/

asq/v3/v3i2a6.htm) Accessed 17 March 2005

Bishop J and Landell-Mills N

2002 Forest environmental ser-

vices: an overview in Pagiola S, Bishop J and Landell-Mills N

eds Selling forest environmental services: market-based

mechanisms for conservation and development

Earthscan,

London 1535

Brown K

2002 Innovations for conservation and development

The Geographical Journal

168 617

Brown K and Rosendo S

2000 The institutional architecture of

extractive reserves in Rondnia, Brazil The GeographicalJournal

166 3548

Buck L, Geisler C, Schelhas J and Wollenberger E

eds 2001

Biological diversity: balancing interests through adaptive

collaborative management

CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

Conklin H

1954 An ethnographic approach to shifting agricul-

ture Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences17

13342

Dahl O 1991 Migration from Kalimantan to MadagascarNor-

wegian University Press, Institute for Comparative Research

in Human Culture, Oslo

DEF (Direction des Eaux et Forts, Deutsche Forstservice

GmbH, Enterprise dEtudes de Dveloppement Rural

Mamokatra and Foiben-TaosarintaninI Madagasikara) 1996Inventaire ecologique forestier national: situation de dpart,

rsultats, analyses et recommandations Ministre de lEnvi-

ronnement, Plan dActions Environnementales, Programme

Environnemental Phase 1, Direction des Eaux et Forts,

Rpublique de Madagascar

Ford R and McConnell W 2001 Linking geomatics and partici-

pation to manage natural resources in Madagascar in Buck L,

Geisler C, Schelhas J and Wollenberger E eds Biological

diversity: balancing interests through adaptive collaborative

managementCRC Press, Boca Raton, FL 385405

Gibson C, McKean M and Ostrom E 2000 Explaining deforesta-

tion in Gibson C, McKean M and Ostrom E eds People and

forests: communities, institutions and governanceMIT Press,Cambridge, MA 126

Green G and Sussman R 1990 Deforestation history of the

eastern rainforests of Madagascar from satellite images Science

248 21215

Jarosz L 1993 Defining and explaining tropical deforestation:

shifting cultivation and population growth in colonial Mada-

gascar (18961940) Economic Geography69 36679

Keck A, Sharma N and Feder G 1994 Population growth, shift-

ing cultivation, and unsustainable agricultural development:

a case study in Madagascar Africa Technical Department

Series World Bank Discussion Paper 234, Washington DC

Kull C 1996 The evolution of conservation efforts in Madagascar

International Environmental Affairs8 5086

-

8/2/2019 McConnell Sweeney 2005_Challenges of Forest Governance

16/16

238 Challenges of forest governance in Madagascar

Laney R 2002 Disaggregating induced intensification for land-

change analysis, Madagascar Annals of the Association of

American Geographers92 70226

Larson B 1994 Changing the economics of environmental

degradation in Madagascar: lessons from the National

Environmental Action Plan process World Development 22

67189

Marcus R and Kull C 1999 Setting the stage: the politics

of Madagascars environmental efforts African Studies

Quarterly3(2) art 1 (http://web.africa.ufl.edu/asq/v3/v3i2a1.htm)

Accessed 17 March 2005

Mausel P, Wu Y, Li Y, Moran E and Brondzio Y 1993 Spectral

identification of successional stages following deforestation in

the Amazon Geocarto International8 6181

McConnell W 2001 Misconstrued land use in Vohibazaha:

participatory planning in the periphery of Madagascars

Mantadia National Park Land Use Policy19 21730

McConnell W 2002 Madagascar: emerald isle or paradise lost?Environment44 1022

McConnell W, Sweeney S and Mulley B 2004. Physical and

social access to land: spatio-temporal patterns of agricultural

expansion in Madagascar Agriculture, Ecosystems and

Environment101 17184

McGinnis M 1999 Introduction in McGinnis M ed Polycentric

governance and development: readings from the Workshop

in Political Theory and Policy Analysis The University of

Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI 128

Messerli P 2000 Use of sensitivity analysis to evaluate key

factors for improving slash-and-burn cultivation systems on the

eastern escarpment of Madagascar Mountain Research and

Development20 3241

Nelson R and Horning N 1993AVHRR-LAC estimates of forest

area in Madagascar, 1990 International Journal of Remote

Sensing14 146375

Ostrom E and Wertime M 2000 International Forestry

Resources and Institutions research strategy in Gibson C,

McKean M and Ostrom E eds People and forests: communities,

institutions and governanceMIT Press, Cambridge, MA 24362

Rakotozafy V, Andriamalala C and Raharison R 2002 Institu-

tional roles in local management of forest resources in Mada-

gascar Paper presented at the meetings of the International

Forestry Resources and Institutions, Kampala, Uganda

Ribot J 1995 From exclusion to participation turning Senegalforestry policy around World Development23 158799

Schoonmaker-Freudenberger K 1995 Tree and land tenure:

using rapid appraisal to study natural resource management:

a case study from Anivorano, MadagascarFAO, Rome

Twyman C 2000 Participatory conservation: community-based

natural resource management in Botswana The Geographical

Journal166 32335