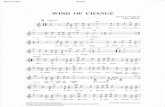

Making It #2 - Wind of Change

-

Upload

making-it-magazine -

Category

Documents

-

view

6.434 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Making It #2 - Wind of Change

MakingItIndustry for Development

Timeto go

green?

Number 2

Windof

change

� Bianca Jagger: After Copenhagen � Suntech Power� Energy transitionsfor industry� Carbon captureand storage

A new quarterly magazine.Stimulating, critical andconstructive. A forum fordiscussion and exchangeabout the intersection ofindustry and development.

Issue 1, December 2009�Rwanda means business: interview with President Paul Kagame�How I became an environmentalist: A small-town story with global

implications by Phaedra Ellis-Lamkins, Green For All� ‘We must let nature inspire us’ – Gunter Pauli presents an alternative

business model that is environmentally-friendly and sustainable�Old computers – new business. Microsoft on sustainable solutions

for tackling e-waster�Green industry in Asia: Conference participants interviewed�Hot Topic: Is it possible to have prosperity without growth? Is ‘green

growth’ really possible?�Policy Brief: Greening industrial policy; Disclosing carbon emissions

MakingIt 3

The theme of this – the second – issue of Making It: Industry forDevelopment is energy, specifically the provision of energy to spursustainable development, to facilitate productive activities bypowering tools, machinery, and manufacturing processes in waysthat will cause less – ideally no – damage to our environment.

The world cannot address the threat of climate change withoutdealing with the issues of energy access and energy solutions. We cannot fight poverty without creating wealth, and it’s notpossible to create wealth without a cheap source of energy topower economic activities. And we can’t achieve any of theMillennium Development Goals without improving access toaffordable and reliable sources of energy.

What are the renewable energy options for developingcountries? How can industries across the globe increase output to meet a growing demand while, at the same time, reducegreenhouse gas emissions? What needs to be done to give theworld’s poorest people access to energy, and how can it be done?

Energy for development is a vast topic, and Making It hopes toact as a thought-provoker, and as a catalyst for a wider and deeperdiscussion and debate.

Making It’s new website – www.makingitmagazine.net– provides an interactive platform for exchange of

views and ideas, and we invite you – our readers– to join in. We want to know how you see thistopic, what energy for development means toyour country, your community, yourbusiness. If you agree, or disagree, or even ifyou think our contributors have missed the

point, we want your reactions, your response.

Editorial

Editor: Charles [email protected] committee: Ralf Bredel,Tillmann Günther, Sarwar Hobohm,Kazuki Kitaoka, Ole Lundby (chair), Cormac O’ReillyCover illustration by PatrickChappatte – www.globecartoon.comDesign: Smith+Bell, UK –www.smithplusbell.comThanks for assistance to LaurenBrassaw, Donna Coleman, andDaisy Lau C.F.

Printed by Imprimerie CentraleS.A., Luxembourg – www.ic.luon PEFC certified paper

To view this publication online and toparticipate in discussions aboutindustry for development, please visitwww.makingitmagazine.netTo subscribe and receive futureissues of Making It, please send anemail with your name and address [email protected] It: Industry for Developmentis published by the United NationsIndustrial DevelopmentOrganization (UNIDO)Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 300, 1400 Vienna, AustriaTelephone: (+43-1) 26026-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26926-69E-mail: [email protected] © 2010 The UnitedNations Industrial DevelopmentOrganization No part of this publication can beused or reproduced without priorpermission from the editorISSN 2076-8508

Contents

GLOBAL FORUM6 Letters7 After Copenhagen – Bianca Jagger10 Hot topic – The pros and cons of biofuels

14 Business matters – News, trends,innovations, and events

FEATURES16 Renewable energy options in developingcountries – José Goldemberg and OswaldoLucon review the current state of play19 Energy transitions for industry – Nobuo Tanaka, Executive Director of theInternational Energy Agency

22 KEYNOTE FEATUREEnergy for all – Kandeh Yumkella, Director-General of the United Nations IndustrialDevelopment Organization, and LeenaSrivastava, Executive Director of the Energyand Resources Institute, on what needs to bedone to improve energy access

MakingItIndustry for Development

The designations employed and thepresentation of the material in this magazinedo not imply the expression of any opinionwhatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of theUnited Nations Industrial DevelopmentOrganization (UNIDO) concerning the legalstatus of any country, territory, city or area orof its authorities, or concerning thedelimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, orits economic system or degree ofdevelopment. Designations such as“developed”, “industrialized” and “developing”are intended for statistical convenience and donot necessarily express a judgment about thestage reached by a particular country or area inthe development process. Mention of firmnames or commercial products does notconstitute an endorsement by UNIDO.The opinions, statistical data and estimatescontained in signed articles are theresponsibility of the author(s), including thosewho are UNIDO members of staff, and shouldnot be considered as reflecting the views orbearing the endorsement of UNIDO.This document has been produced withoutformal United Nations editing.

MakingIt4

30

Number 2, April2010

30 Women entrepreneurs transformingBangladesh – Dipal Barua says renewableenergy systems can help empower womenand create jobs32 Everywhere under the sun – Zhengrong Shi,founder and CEO of Suntech Power, extolsthe virtues of nature’s most abundant energyresource36 Energy for development – Interview withAustria’s Foreign Minister, MichaelSpindelegger

40 Carbon capture and storage – Statoil CEO,Helge Lund, explains how CCS can helpmitigate climate change

POLICY BRIEF42 Financing renewable energy43 How policy-makers can make a difference 44 Getting FiT: Feed-in tariffs

46 Endpiece – Alice Amsden on industrialpolicy and poverty reduction

16

40

MakingIt 5

1922

LETTERS

MakingIt6

Microsoft and e-wasteI am surprised to see thatMaking It (Issue 1, December2009) has Microsoft writingabout e-waste. Greenpeace hasjust released its newest Guideto Green Electronics, evaluatingthe top 18 manufacturers ofpersonal computers, mobilephones, TVs, and gamesconsoles based on theirpolicies on toxic chemicals,recycling and climate change.Microsoft drops two placessince the last evaluation, and isnow in place 17 of 18companies!

The Greenpeace report statesthat: “On e-waste, Microsofthas now engaged in an EUcoalition supportingIndividual ProducerResponsibility... (but) on othere-waste criteria, Microsoft failsto score any points.”

Specifically it states,“Microsoft provides links tovarious recycling initiatives byMicrosoft (MAR, DigitalPipeline), other organisations(eg. CEA’s myGreenElectronics)and other electronicmanufacturers, but it still doesnot provide free take-back forits own products.” Andcontinues, “Microsoft is usingrecycled plastics in productpackaging films but no detailsare given about its use inhardware products.” �Constantine Simpson,received by email

A Microsoft spokespersonsent the following response: Microsoft’s commitment toenvironmental sustainabilityincludes strategies to minimizethe impact of our operations;using IT to improve energyefficiency; and acceleratingresearch breakthroughs that willhelp scientific understanding ona global scale. We acknowledgethat more work remains toachieve our sustainability goalsand continue to work to improveupon our efforts.

In our consumer electronicsbusiness, we comply with or exceedall applicable environmentalguidelines and regulations. We arecommitted to making progress onenvironmental issues withoutdetracting from the durability,safety, performance, and affordablecost that consumers demand. Weconstantly look for ways to be moreefficient, use fewer materials, andalways seek continuousimprovement, while keepingquality up and cost down.Moreover, we have eliminatedsubstances and reduced materialswithout sacrificing ourcommitment to consumer safety,innovation, and quality.

Time to go green!Making It magazine is a verywelcome contribution toUNIDO’s efforts to stimulatethe debate on development andto make itself known to a widerpublic. It uses plain terms anddoes not shun controversy. Ihave been a regular UNIDOconsultant over the past quarterof a century, and I have not seen

such a publication. I wish itevery success.

In relation to the Hot Topicarticles around the theme of‘prosperity without growth’ inthe first issue: with regard tonature, manufacturing has so farbasically assumed that it’spossible to have a free lunch – itdoes not return to the biospherewhat it takes from it. We havefinally understood that this is aproblem. The title on the coverof the first issue of Making It–‘Time to go green’ – should havebeen followed by an exclamationmark, not a question mark. � Paul Hesp, received by email

Environmentalconcerns aluxury?This is a good article (“How Ibecame an environmentalist’’ –Making It, Issue 1), but I wonderhow Ms Ellis Lamkins wouldfind it in a much poorercountry. California is certainlynot a poor place, and I wonderif the environment meanssomething also to people wholive on only a few cents everyday in Africa and Asia? �Marko Simic, received byemail

The Making It editor responds:I think Ellis-Lamkins’ article ismaking the point that health andsafety, and the environment, areimmediate concerns to workers incountries all over the world. As shewrites, parents want to “keep theirchildren and communities healthy,safe, and economically viable.”

HookedSeeing the first issue ofMaking It, one cannot be butimpressed by the quality ofthe production: first andforemost in terms of content,then the lay-out, colour anddesign. While the markettrend is from print to digital,this print version travels withme! Having started threepublishing ventures myself, Iknow it takes professionals toget the reader hooked on yourmaterial, and you certainly didit for me.� Prof. Gunter Pauli, founderof Zero Emissions Researchand Initiatives, author of TheBlue Economy, Tokyo, Japan

BrilliantThank you very much forproviding me with a copy ofyour magazine. As a formerAustrian representative to theUN, and the current Chairmanof the Advisory Board of theEuropean Training Centre forHuman Rights andDemocracy, I look forward tofuture issues. With bestregards, and all good wishesfor this brilliant initiative.�Walther Lichem, Vienna,Austria

The Global Forum section of Making It is a spacefor interaction and discussion, and we welcomereactions and responses from readers about any

of the issues raised in the magazine. Letters for publication in Making It should be marked ‘For publication’, and sent either by email to: [email protected] or by post to: The Secretary, Making It, Room D2226, UNIDO, PO Box 300, 1400 Vienna, Austria. (Letters/emails may be edited for reasons of space).

To provide a platform for further discussion of the issues raised in Making It, a magazinewebsite has been created at www.makingitmagazine.net and readers are encouraged to surf onover to the site to join in the online discussion and debate about industry for development.

GLOBAL FORUM

GLOBAL FORUM

MakingIt 7

The experience of participating at theCopenhagen climate change summit(COP15) in December is not one I willeasily forget. It was a unique opportunityto set the world on the right path to avoidcatastrophic climate change. For twodays, most of the world’s leaderscongregated under one roof for acommon purpose. Attended by 120Heads of State, COP15 was the largestgathering of its kind held outside of theannual UN General Assembly in NewYork. The two weeks of meetings,extending late into the night, marked theculmination of two years of intensivenegotiations. The conference was thefocus of unprecedented public andmedia attention. And yet, the result – theCopenhagen Accord – was a shamefulcompromise.

Yvo de Boer has recently announced hisintention to stand down as head of theUnited Nations Framework Conventionon Climate Change (UNFCCC). In the run-up to COP15 he was unequivocal about theconference being successful only if itdelivered significant and immediateaction. Sadly, COP15 failed to deliver.

Henry Ford once said that “most peoplespend more time and energy going aroundproblems than in trying to solve them”,and this was true of all too many of thenegotiating positions on display at COP15.Those leaders and negotiators must takefull responsibility for their actions.

Not legally bindingThe failure at Copenhagen has been feltacross the world, resulting in graveuncertainty about the ability of world

leaders to deliver a comprehensive, legallybinding, international climate changetreaty. The words “legally binding” wereconspicuously absent from the three-pagetext of the Copenhagen Accord. TheAccord is merely “politically binding” forthose countries that choose to sign up toit. Furthermore, it does not set emissionsreduction targets for either 2020 or 2050,nor does it set a deadline by which theaction points should become enforceable.

The Conference of Parties inCopenhagen did not even “adopt” theAccord. They “took note” of it. Rob Fowler,chair of the IUCN Academy ofEnvironmental Law, commented, “Theexact status of the so-called ‘CopenhagenAccord’ ...is unclear... (It) fails to achieveeven the status of a ‘soft-law’ instrument,and thus constitutes the most minimaloutcome conceivably possible.”

The end of the meeting saw leaders ofthe United States and the BASIC Group ofcountries (Brazil, South Africa, India andChina) hammering out a last-minute dealin a back room. It was as though the ninemonths of preparatory talks had neverhappened, and the Bali Action Plan

BIANCA JAGGER, who attended the climate changeconference in Copenhagen in December 2009, is stronglycritical of the resulting accord, and calls for immediateand concrete steps to avert climate catastrophe.

AfterCopenhagen

� In 2004, BIANCA JAGGER received the Right Livelihood Award, known as the‘Alternative Nobel Prize’, for her “long-standing commitment and dedicatedcampaigning over a wide range of issues of human rights, social justice, andenvironmental protection”. She is the founder and chair of the Bianca JaggerHuman Rights Foundation. �

GLOBAL FORUM

MakingIt8

adopted in 2007 had never existed. Thisgroup found it easier to reach a (non)-agreement behind closed doors on a fewbasic points of principle, rather than workout a treaty via the formal UNFCCCprocess. Although the European Unionhad been the clear global leader in thefight against climate change dating backto COP3 in 1997 when the Kyoto Protocolwas adopted, it was not involved in thismeeting. UNFCCC participants werepresented with a fait accompli perceived bymany as a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ ultimatum.

The Copenhagen Accord did not achieveunanimous consent – several partiesraised points of order. As Tuvalu’s PrimeMinister Apisai Ielemia said, in the UNsystem “nations large and small are givenequal respect; the public announcementof a deal before bringing it before the COPmeeting was disrespectful of the processand the UN system.” He highlightedmajor problems with the politicalagreement, saying it lacked a scientificbasis, an international insurancemechanism, and guarantees on thecontinued existence of the Kyoto Protocol.“We came here expecting an open andtransparent process. Unfortunately this isnot happening.”

What transpired at Copenhagen leftdeveloping countries frustrated abouttheir marginalization by the developedworld, about their exclusion from policymaking, and about the lack oftransparency in the way the negotiationswere conducted.

350 parts per millionThe Copenhagen Accord acknowledgesthat a rise of more than two degreesCelsius is catastrophic, but it contains nofirm commitments to address thisimpending global crisis. Professor JamesHansen, Head of the NASA GoddardInstitute for Space Studies is emphatic:“The safe upper limit for atmospheric

CO2 is no more than 350 parts per million(ppm).” Atmospheric levels are currentlyhovering at around 389ppm.

The UN Programme on ReducingEmissions from Deforestation and ForestDegradation in Developing Countries(REDD) was supposed to have been part ofthe legally binding treaty. Emissions fromdeforestation account for approximately20% of greenhouse gas emissions, and theStern Review of the Economics of ClimateChange argues that “curbing deforestationis a highly cost-effective way of reducinggreenhouse gas emissions.” Planting 10million square kilometres of naturalforests will help stabilize theconcentration of CO2 in the earth’satmosphere at the 350ppm that ProfessorHansen prescribes.

In the absence of a legally binding treaty,the implementation of REDD rests onvoluntary, country-driven activity. Thelowest estimates on the financing ofREDD are predicted to be US$22.4 – $37.3billion from 2010-15 just to support

preparatory activities. To date, sixdeveloped nations, Australia, France,Japan, Norway, the UK and the US, andhave pledged a total of US$3.5 billion tosupport the implementation of REDDbetween 2010 and 2012.

The Accord does contain a commitmentby developed countries to pay thedeveloping world US$30 billion of“climate aid” over the next three years, with the aim of increasing this amount toUS$100 billion a year from 2020. Howeverthis offer is not legally binding. There is nomention of which countries will receivefinancing, in which amounts, on whatconditions, or under which mechanisms.

Vapour moneyEven concrete financing pledges can beunpredictable, conditional, and selectivewhen implemented, and the finance‘goals’ contained in the Accord areanything but concrete. As ProfessorHansen puts it, even the money promisedto developing countries is “…vapour

�

MakingIt 9

GLOBAL FORUM

money. There’s no mechanism for suchfinancing to actually occur, and noexpectation that it will.”

‘Vapour money’ is not good enough. Wemust call for a concrete fiscal plan toincentivize sustainable development.There were no ‘goals’ when governmentswere delivering bailouts to the banksduring the recent global financial crisis.The amount of money put up by theUnited States alone to save its banks wasUS$750 billion.

After the Copenhagen meetingconcluded, the French newspaperLibération lamented the speed andcommitment to saving the planetcompared with saving the global financialsystem: “We must make the bitterobservation: when it comes to rescuingthe banking system, the dialogue has beenfar more effective and determined. It isclearly easier to save finance, than it is tosave the planet.”

The question of how to move forward isa tough one. How do we achieve acontractual commitment, when worldleaders, brought together for onepurpose, and with all the resources of theCOP15, failed?

First vital testCountries were asked to submit theirvoluntary proposed domestic greenhousegas (GHG) reduction pledges in acommon document by January 31st, 2010.This was the first vital test of the Accord’srelevance. By mid-February, 55 countrieshad submitted plans to cut GHGemissions. The most significant target todate has been set by Norway, whichpledged 30-40% reductions by 2020.Similarly, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Japan,and Iceland have made commitments toreduce GHG emissions in the range of30%, and the EU has committed to a 20-30% reduction. All of these countries havebased their reductions relative to 1990

levels. By contrast, the United States andCanada have framed their pledges indeceptive terms, offering to reduceemissions by 17% relative to 2005 levels,which amount to a mere 3.2% reductionrelative to 1990 levels.

India, the world’s fifth largest polluter,has pledged to reduce carbon emissionsby 20-25% by 2020, relative to 2005 levels,although there is no indication whatmeasures they will take to meet the goal.Similarly, China “will endeavour to reduceits emissions per unit of GDP by 40 to 45%by 2020.” China’s plan also includes“increasing the share of non-fossil fuels inprimary energy consumption to around15% by 2020, and increasing forestcoverage by 40 million hectares and foreststock volume by 1.3 billion cubic meters by2020 relative to 2005 levels.”

Commitment to the Accord andcountries’ adherence to their own targetswill be entirely self-monitored. Somestates have indicated their support for theAccord, but have submitted no targets to

date. Some have submitted reductiontargets, but have not indicated supportfor the Accord.

Immediate actionThe failure of world leaders to broker aglobal, comprehensive, legally bindingtreaty was an appalling abdication ofresponsibility. I am not being alarmist;the situation is alarming. The time forfurther excuses and postponements, forprocrastination or prevarication, haslong passed. Now is the time fordecision-makers in politics andeconomics to take concrete steps to avert climate catastrophe; the time forcourage and leadership, and forimmediate action. Tackling climatechange is the over-riding moralimperative of the century. Our future,the fate of future generations, and thefuture of all other species on this planethangs in the balance.

Now, more than ever, nations, societies,communities, and individuals areinterconnected and interdependent. It isan intellectual illusion to believe that thecrises that besiege our world today canbe compartmentalised, and that we canaddress them without revolutionizingour way of life. Climate change will affecteveryone, everywhere, in every state, andfrom every socio-economic group, inhundreds of ways: from the pollution ofcities to erosion in rural areas; fromcontamination of the oceans and riversto desertification; from mass migrationto overcrowded cities, and the security ofindividuals and states. We must changethe way we live, eat, think, do business,and travel, in order to build a society on asolid sustainable foundation.

We cannot do this without cooperationbetween nations, states, leaders, parties,organizations, and individuals. At thiscritical juncture in history, we will eitherstand or fall together. �

“I am not being alarmist; the situation is alarming. The time for further excusesand postponements, for pro-crastination or prevarication,has long passed.”

MakingIt10

GLOBAL FORUM

JEAN ZIEGLER, vice-chairperson of theAdvisory Committee of the United NationsHuman Rights Council, and former UnitedNations Special Rapporteur on the Right toFood (2000-2008).

Every five seconds a child below ten yearsof age dies from hunger. Every fourminutes somebody loses his/her eye-sightfrom a lack of Vitamin A. Every day 25,000people die from hunger, or immediately-related causes. Over one billion people aregravely, permanently, undernourished.One of the most brutal consequences ofmalnutrition is noma, a devastatingdisease that mainly affects children underthe age of 12. The disease leaves a terriblehole in the child’s face – that is if theysurvive, given the death rate of 80-90%. Itis a shocking reality, and an odious ironythat the same Food and AgricultureOrganization report which gives thenumber of the victims of world foodinsecurity, indicates that global agriculturein its present stage of development could,without problem, nourish twelve billionpeople, i.e. almost double the currentworld population.

In recent years, biofuels have beenpraised as not only a solution to climatechange and energy insecurity, but also asan option that can address the food

insecurity that ravages parts of the world.However, even before the peak of the foodcrisis in 2008, when the controversyregarding biofuels reached its climax,concerns were being voiced about theeffect that increased biofuel productioncould have on the right to food.

Environmental impactRecent research shows that biofuels, in andby themselves, do not represent anenvironmental panacea. Whether biofuelsare ‘green’, and offer carbon savings,depends on how they are produced. Sugarcane, for example, is considered to be veryeffective for the production of bioethanol,and the consumption of the latter is lessdamaging to the environment than is theuse of conventional fuels. Nonetheless, the

benefits of bioethanol diminishconsiderably if carbon-rich tropical forestsare being converted into sugar caneplantations, thereby causing vast increasesin greenhouse gas emissions. According toone estimate, converting rainforests,peatland, savannas, or grasslands intofields to produce food crop–based biofuelsin Brazil, Malaysia, Indonesia, and theUnited States, creates a “biofuel carbondebt”. The process will create up to 420times more CO2 than the annualgreenhouse gas reductions that thesebiofuels would provide by replacing fossilfuels. Biofuel production, in suchconditions, has the function of anenvironmental Trojan horse.

On large-scale palm oil plantations inBorneo and Sumatra, and on sugar canefarms in Brazil, water waste and waterpollution, overuse of fertilizers, soilerosion, localized air pollution due tochemical spraying, and burning the landafter the harvest, are all major problems.The negative environmental effects ofbiofuel production clearly have an impacton the realization of the right to food formillions of people in the medium andlong term, in particular those groupswhich require accesses to fertile soil andclean water to grow their food.

Food pricesIn the 2007 Special Rapporteur’s report tothe United Nations General Assembly, Iraised the issue of the role biofuels playin the increase in international foodprices. Many other expert voices havesince made the same link. A World Bankstudy estimates that 70-75% of theincrease in food commodity prices from2002 to 2008 was due to biofuels, and therelated consequences of low grain stocks,large land-use shifts, speculative activity,and export bans. The InternationalMonetary Fund’s John Lipsky estimatesthat the use of food crops, especially

Biofuels: a right tofood perspective

In what is a regular feature, Making It invites distinguishedcontributors to consider one of the controversial issues of the day.The debate continues: what are the pro and cons of biofuels?

“A World Bank studyestimates that 70-75% of theincrease in food commodityprices from 2002 to 2008 wasdue to biofuels”

HOT TOPIC

MakingIt 11

GLOBAL FORUM

maize, to make bioethanol, is responsiblefor at least 40% of the price explosion.Subsidies and other fiscal tools aimed atpromoting the use of biofuels, inparticular in the USA and the EuropeanUnion, have decisively contributed to arising demand for sugar, maize, wheat,oilseeds, and palm oil. The incentive toproduce crops for biofuels was furtheraugmented by the high price of oil, whichmade biofuels an even more attractivealternative to fossil fuels. A food/fuelcompetition could be observed as globalwheat and maize stocks declinedconsiderably. The stronger demand forthese food commodities as biofuel inputscaused a surge in their prices in worldmarkets, which in turn resulted in higherfood prices. The International FoodPolicy Research Institute projects that thenumber of people suffering fromundernourishment could increase by 16million for each percentage pointincrease in the real price of staple food.

Vulnerable groupsCareful attention needs to be paid to thevarious social impacts that theproduction of biofuels have on vulnerablegroups. The development of biofuelproduction potentially does have animportant role to play in povertyreduction, and hence in realizing theright of everyone to an adequate standardof living, including food security.Nonetheless, experience has shown thereare other less welcome social impacts.

The expansion of biofuel production inLatin America, and parts of South-eastAsia and Africa, has resulted in violationsof land rights and forced evictions – thishas been thoroughly documented inmany studies and reports by UN agencies.Among those who are particularly affectedare indigenous peoples, smallholders, andforest dwellers. Furthermore, whendiscussing land rights, it is essential totake gender into account. Land tenuresystems throughout the world are

systematically discriminating againstwomen, very often making land rightsdependent on marital status. In thiscontext, the increase in biofuel cropproduction may come at a high cost to thefood security of rural women, who willrarely be able to mount a legal challengeto their displacement by powerfulagribusinesses. Along these lines, landconcentration – the acquisition of largeportions of land usually by foreigncorporations or states – may lead, as oneanalyst warns, to a “process ofmarginalization or eviction ofsmallholders to an unprecedenteddegree, transforming them either intobadly-paid workers or swelling thenumber of urban poor.”

Less jobsSome proponents present biofuels as a realopportunity for employment creation, andthus implicitly beneficial for the foodsecurity of those employed. Empiricshowever offer a more complex – if not acontradictory – reality. In countries wherethere has been a strong expansion inbiofuel production, employment infarming appears to have decreased, and agrowing trend for seasonal jobs isobservable. The increasing mechanizationof the harvest process means that long-term employment predictions must benegative. If we agree that more jobs meanmore food security, then less jobs and lessstable jobs clearly point to food insecurityand a threat to the realization of the rightto food.

An alarming number of reports byNGOs and governmental andintergovernmental agencies areemphasizing the often catastrophic wagesand horrific working conditions in palmoil and sugar cane plantations. A system ofdebt bondage can be observed, whicheffectively subjects workers to slave-likerelations with the owners of the �

MakingIt12

GLOBAL FORUM

STEPHEN KAREKEZI and JOHN KIMANI –AFREPREN/FWD (Energy, Environment,and Development Network for Africa), anon-governmental organization based inNairobi, Kenya.

Recent high oil and coal prices, as well asan intensified debate about climatechange, have led many analysts to suggestthat modern bioenergy development couldmitigate the negative impacts of unstablefossil fuel prices and continued reliance oninefficient and unhealthy traditionalbiomass energy options, as well ascontribute to reducing greenhouse gasemissions. Consequently, over the lastthree to four years, many sub-SaharanAfrican countries have started modernbioenergy initiatives, and a number ofthem have rushed into agreements withinternational investors for large-scaleliquid biofuel development.

Some countries have allowed theclearing of virgin forest land, as well as theconversion of land suitable for food cropsinto fields for biofuel crops, with probableadverse impacts on forest stocks and foodsecurity. In addition, many of the newbiofuel programmes are not designed tomeet internal demand, but are largelyaimed at international export markets,especially the European Union (EU), whichhas announced ambitious biofuel targets.

The above developments have led someAfrican governments to implementmeasures that limit the direct productionof bioenergy (particularly liquid biofuel)from food crops and/or from formerfood-producing farmlands. For example,

in 2008, the President of the UnitedRepublic of Tanzania banned thecultivation of jatropha in a regionearmarked for rice production.

The controversy over liquid biofueldevelopment in sub-Saharan Africa hasovershadowed less well-known, butsuccessful, biofuel options that deliversignificant positive impacts to both ruralsmall-scale farmers and nationaleconomies in sub-Saharan African. One of the most significant of these is highpressure cogeneration from the by-products of cane sugar production.

Cogeneration Cogeneration is the simultaneousproduction of electricity and process heatfrom a single dynamic power plant. Acogeneration power plant burns bagasse(the fibrous residue remaining aftersugarcane stalks are crushed to extracttheir juice) to generate steam for processheat, and for driving a turbine to produceelectricity. Bagasse-based cogenerationutilizes the waste material which isotherwise a nuisance for sugar refineries –it is a fire hazard, as well as anenvironmental concern as thedecomposition of bagasse releasesmethane, a more potent greenhouse gasthan carbon dioxide.

Bagasse-based cogeneration is not a newtechnology in the sub-Saharan Africansugar industry, but what is novel is the useof highly efficient cogenerationequipment to create an increasinglyimportant source of commercial energysupply. Leading in this process is

Bioenergy developmentin sub-Saharan Africa plantation and/or other intermediaries.

Hunger and the need to feed theirfamilies leads individuals to acceptappalling working conditions – at timesbordering on or equivalent to slavery.

Structural reformsWe have to start assessing biofuels throughthe prism of the one billion hungry peopleon the planet today. In other words,governments have to meet their legalresponsibility to respect, protect, and fulfiltheir populations’ right to food. Hence, ifbiofuel production is to be expanded, thenstructural reforms are necessary to addressstructural issues. We cannot just pay lip-service to the well-being of current andfuture generations. There must be landreforms targeted at empoweringvulnerable groups, such as landlesslabourers, forest dwellers, smallholders,indigenous groups, and women. Budgetsneed to be adjusted to support suchprogrammes, and to reflect theprioritization of vulnerable groups withrespect to the right to food. And legislativemeasures that promote inclusive models –such as Brazil’s Pro-Biodiesel programme– should be replicated and pursued as apriority. Such measures would bringbiofuels closer to being able to deliver thepromised social solution.

Meanwhile, developed countries – partlyresponsible for the growing demand forbiofuels as a result of their subsidyschemes – must acknowledge and addressthe social and environmental effects of theproduction, and the expansion ofproduction, of biofuels. After all, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote many years ago,“Between the powerful and the weak, it isliberty that oppresses and it is the law thatliberates.” The right to food must beupheld by all. �

HOT TOPIC�

MakingIt 13

GLOBAL FORUM

development has resulted neither in anincreased competition for land, nor in anincrease in food prices – the two mostnotable negative impacts of large scalebioenergy development. In fact, over time,while increased cogeneration developmenthas led to additional electricity supply, theland area on which sugarcane is cultivatedhas been declining – implying thatincreased efficiency in cogeneration haspartly led to freeing up land for other uses,including food production.

Several other sub-Saharan Africancountries have already begun to follow inthe footsteps of Mauritius. Ethiopia, Kenya,Malawi, Sudan, Swaziland, Uganda and theUnited Republic of Tanzania, are takingpart in ‘Cogen for Africa’, an innovative,regional, clean energy initiative funded bythe Global Environment Facility andimplemented by AFREPREN/FWD.

The potential for sub-Saharan Africa as awhole is significant. Based on current sugarproduction in sub-Saharan Africa, bagasse-based cogeneration from sugar industriescan meet about 5% of the total electricity

Mauritius, where, thanks to the extensiveuse of bagasse-based cogeneration, thecountry's sugar industry is self-sufficientin electricity and is able to sell the excess tothe national grid. The sugar industry isnow contributing over half of theelectricity supply on the island.Cogeneration in Mauritius is designed touse bagasse during the cane harvestingseason (roughly six months), with coalused to generate the electricity supply forthe rest of the year.

Bagasse-based cogenerationdevelopment in Mauritius has delivered anumber of benefits, including reduceddependence on imported oil,diversification in electricity generation,improved efficiency in the power sector ingeneral, and increased incomes forsmallholder sugar farmers. It has alsohelped sugar factories in Mauritius toweather fluctuations in global sugar prices,including the reduction in the EU’spreferential sugar prices to African,Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries. Inrecent years, the revenue from the sale ofexcess electricity from cogeneration hasenabled Mauritian sugar factories toremain profitable.

Revenue sharingPerhaps one of the most importantachievements is the use of a wide variety ofinnovative revenue sharing measures. Forexample, the Mauritian cogenerationindustry has worked closely with thegovernment to ensure that substantialmonetary benefits from the sale ofelectricity from cogeneration flow to allkey stakeholders of the sugar economy,including the poor, smallholder, sugarfarmers. The equitable revenue sharingpolicies in Mauritius provide a model forongoing and planned bioenergy projectsin other sub-Saharan African countries.

Another important development to noteis that, in Mauritius, cogeneration

demand in the region. If biomass wastefrom other agro-industries and fromforestry industries is included, about 10%of electricity in the region could begenerated through cogeneration.

Key lessonThe key lesson from the success ofbagasse-based cogeneration in Mauritius isthe need to prioritize the effective use ofexisting agricultural wastes for conversioninto modern bioenergy fuels. This optionhas the least adverse impact on the poor,and could provide additional revenue forpoor, rural communities. However, itrequires establishing effective revenue-sharing mechanisms that ensure that thehigher revenues from the exploitation ofagricultural wastes are shared in anequitable fashion, and flow to allstakeholders, especially to the low-incomefarmers. It also requires enacting a legaland regulatory framework that allows forthe development of modern agro-waste-based bioenergy, and that provides, amongother incentives, access to the power gridand transport fuel market. In some cases,mechanisms for efficient centralization ofagricultural wastes would also need to bein place.

Once sub-Saharan African countries haveoptimized the use of existing agriculturalwastes for energy generation, and put inplace adequate revenue-sharing, regulatory,and policy frameworks, they can considerthe option of large-scale bioenergyplantations, while carefully balancing anyassociated trade-offs between food securityand energy generation. Fortunately, thetechnical, regulatory, and policy expertiseneeded to promote an equitableagricultural waste energy industry in manycases also provides the skills needed todevelop and nurture a sustainable,dedicated bioenergy plantation sector thatdoes not adversely affect the poor ordecrease food security. �

Tim

Gra

ham

/Get

ty Im

ages

Sugar processingplant, Mauritius.

MakingIt14

�The pace of global growthpicked up in February, with astrong manufacturing sectorleading the way for services, butfirms continued to cut jobs,according to the Global TotalOutput Index, produced by thefinancial services firm, JPMorgan. “The recovery was againfirmly centred on themanufacturing sector, however, asthe rebound in services remainedfragile in comparison,” said thefirm’s David Hensley. (JP Morgan)

� Recent GDP data from acrossthe region suggest that Asianeconomies are in the vanguard of

strong but uneven recovery,according to a report from theManufacturers Alliance/MAPI.The report focuses on LatinAmerica’s three largest economies– Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico –as these countries are responsiblefor more than 80% of themanufacturing output in theregion. MAPI forecasts thatoverall manufacturing output inLatin America will decline 7.9%in 2009, but should rebound in2010 with 5% growth. (MAPI)

� Spending on clean energy heldup better than expected duringthe financial crisis and resultingrecession in 2009, but aconsiderable gap still existsbetween current levels ofinvestment and what is needed tobegin reducing the world’s carbon

In November 2009, the Norwegian company, Statkraft, opened aprototype power plant that generates electricity using the naturalprocess that keeps plants standing upright and the cells ofanimal bodies swollen, rigid, and hydrated. Osmosis occurswhen two solutions of different concentrations meet at a semi-permeable membrane.

At the osmotic power plant at Tofte, near Oslo, the twosolutions used are sea and fresh water, siphoned from near thepoint where they meet at the mouth of a fjord. The sea and freshwater are guided into separate chambers, divided by an artificialmembrane. The salt molecules in the sea water pull the freshwater through the membrane, increasing the pressure on thesea water side. This pressure can be used to turn a power-generating turbine.

The prototype plant at Tofte has a limited production capacity,and is intended primarily for testing and developmentpurposes. Many of the world’s major cities are on river estuarieswhere sea and fresh water are easily available, and Statkraftestimates the total global potential of osmotic power to bearound 1700 terawatt-hours per year – about 10% of the world’scurrent electricity consumption. The company hopes that acommercial osmotic power plant will be constructed within afew years’ time.

Unlike wind and solar power, osmotic power can provide acontinuous source of energy, although seasonal river-levelchanges do cause some fluctuations. Critics also say that scalingup the technology could prove difficult because fundamentalquestions, such as the effect of silt and river bacteria on themembranes’ performance over time, have not been resolved.

Copenhagen, Denmark: Havingset a target of zero carbonemissions by 2025, the citycould meet 50% of its heatingneeds by using its geothermalresources.Larderello, Italy: Boasts the veryfirst geothermal power plant,which opened at the beginningof the 20th century.Reykjavik, Iceland: Abundantgeothermal resources provide

heat for approximately 87% ofIceland’s buildings.Reno, Nevada, USA: City andbusiness leaders are marketingthe city as a geothermal centrefor industrial activities, corporateoffices, and research facilities.Perth, Australia: Aims to be thevery first geothermally-cooledcity, with commercialgeothermal-powered air-conditioning units.

Workersventing ageothermalpipeline.

trends

First osmosis power plant opens

The world’s ten leading geothermal cities

BUSINESS MATTERS

the global recovery. Thailand,Taiwan Province of China, HongKong SAR, and Malaysia allpublished official data showing thattheir economies returned to year-on-year growth in the fourth quarterof 2009. However, the EconomistIntelligence Unit (EIU) believes itwould be a mistake to take thissteady stream of good news as proofthat a rapid, sustainable recovery isunder way in the region. Recentdata were boosted by temporaryfactors, and it also remains unclearto what extent growth is dependenton unsustainable stimulusmeasures rather than autonomousdemand. (EIU)

� China has become the world’ssecond largest industrialmanufacturer, after the UnitedStates. These two countries andJapan produce half of the world’smanufacturing output. In spiteof China’s lead in terms of theabsolute amount of production,Japan is still the world’s mostindustrialized country, in termsof manufacturing value addedper capita, totalling nearlyUS$9,000 compared to US$700for China. (UNIDO)

�The sharp manufacturingrecession in Latin Americaduring 2009 will be followed by a

MakingIt 15

emissions. A recent WorldEconomic Forum (WEF) reportfound that investment in 2009was remarkably resilient atUS$145 billion, down only 6%from US$155 billion in 2008. Thedecline would have probablybeen much bigger if it weren’t forthe billions that governmentsaround the globe poured intoeconomic stimulus programmes.However, according to the WEF,if the increase in global averagetemperatures is to be restrictedto 2°C, low-carbon energyinfrastructure will requireglobal annual investment ofaround US$500 billion perannum. While the next few yearsare likely to see recordinvestment activities, asignificant financing gap ofUS$350 billion still exists. (WEF)

Xianyang, China: Recently designated“China’s Official Geothermal City,”Xianyang is helping China meet itsgoal of 16% of energy use fromrenewables by 2020.Madrid, Spain: Six renewable energyprojects are underway, one of whichis a 8-MW geothermal districtheating project.Masdar City, Abu Dhabi: The city’sgoal is to function 100% onrenewable energy, half of it fromgeothermal resources.Klamath Falls, Oregon, USA:Geothermal energy has been used toheat buildings since the turn of the20th century, and is now used for avariety of purposes includingheating homes, schools, businesses,swimming pools, and for snow-meltsystems for sidewalks and roads. Boise, Idaho, USA: The Boise PublicWorks Department has the largest,direct use, geothermal system in theUnited States.

Source: The Geothermal EnergyAssociation, a trade associationcomposed of US companies whichsupport the expanded use ofgeothermal energy.

A fleet of 15 hydrogen-fuelled three-wheeler vehicles is about to begin servicein New Delhi, India. The auto-rickshawswill carry passengers from the PragatiMaidan metro station to a nearbyexhibition centre.

The Hy-Alfa vehicles, built by theIndian car manufacturer, Mahindra andMahindra, are powered by dedicatedhydrogen-fuelled 400cc internalcombustion engines, and will usecompressed natural gas-style fuel storagetanks. The hydrogen will be supplied byone of the largest merchant hydrogensuppliers in the world, Air Products.

The project, run by the Istanbul-basedInternational Centre for HydrogenEnergy Technologies (ICHET), togetherwith a consortium of companies, hasgreat potential for replication acrossIndia. Hydrogen is a by-product of India’schlor-alkali industry that at the momentis burnt (flared) because there is no usefor it.

Dr. Mathew Abraham, general managerat the Mahindra and Mahindra Researchand Development Centre, said, “The Hy-

Alfa is the first vehicle of its kind in theworld. It runs on nothing but compressedhydrogen gas, and is engineered to runwith absolutely zero emissions, whichmakes it a pleasure to drive on congestedcity roads. Hydrogen is, in fact, thetechnology and fuel of tomorrow, and isthe long term solution to pollution, energysecurity, and CO2 emission-relatedconcerns.”

Hydrogen fuel is expected to be a solution tothe problems created by the high nitrogenoxide emissions from the compressed naturalgas (CNG)-fuelled three-wheelers currently inuse in Indian cities.

PHO

TO: M

AYU

MI T

ERA

O/IS

TOC

K

PRA

KA

SH S

ING

H/A

FP/G

ETTY

IMA

GES

� B4E, the Business forEnvironment Global SummitApril 21-23, Seoul, Republic ofKorea. www.b4esummit.com

� World Geothermal Congressand Exhibition 2010 April 25-30,Bali, Indonesia.www.wgc2010.org/

� Ninth Responsible BusinessSummit May 4-5, London, UK.One of the largest CorporateSocial Responsibilityconferences in Europe.www.ethicalcorp.com/rbs

� Energy Efficiency Global Forumand Exposition 2010 May 10-12,Washington DC, USA.http://eeglobalforum.org/

� Bioenergy Markets Africa:Expanding sustainable bioenergyproduction May 11-13, Maputo,Mozambique. www.greenpowerconferences.co.uk

� Third MediterraneanSustainable Energy Summit 2010May 18-19, Athens, Greece.www.ftbusinessevents.com/medsustainableenergy

� The UN Global CompactLeaders Summit 2010, June 24-25, New York, USA.www.leaderssummit2010.org/

� Green Investments SummitJuly 12-15, Jakarta, Indonesia.www.alleventsgroup.com/gisindo2010/

� Fourth International SolarCities World CongressSeptember 16-19, Dezhou,China. www.chinasolarcity.cn

� World Renewable EnergyCongress XI and Exhibition2010 September 25-30,Abu Dhabi, United ArabEmirates. www.wrenuk.co.uk

events

New Delhi hydrogenthree-wheeler project

MakingIt16

Phot

o: K

iese

lUnd

Stei

n/ist

ock

MakingIt 17

In 2009 the world energy consumption was 11.3billion tonnes of oil equivalent (toe). Energy con-sumption in industrialized countries has basi-cally been stable in the last 10 years, but in therest of the world it has been growing at approx-imately 5% per year. At this rate and based onpresent technologies, the world’s annual energyconsumption could reach 20 billion toe by theyear 2020. The consequences of such growth – approximately 80% of it originating from fossilfuels – could be disastrous for three reasons: � the depletion of fossil fuel resources; � geopolitical problems caused by access tosuch fuels, and � environmental problems, notably globalwarming.

Developing countries are witnessing a sub-stantial growth in their greenhouse gas emis-sions, mostly due to rapid industrializationand transport growth, but also due to the un-sustainable use of fuelwood and subsequentdeforestation.

Solving these problems implies tacklingtheir causes: a huge effort that encompasses ba-sically complementary actions and policies in

terms of energy efficiency (or energy conserva-tion) in order to obtain an equivalent well-beingby using fewer natural resources; renewable en-ergies, which can be used instead of fossil fuels;and new technological advances to improveenergy efficiency and utilize renewable energy.

Energy efficiency extends the life of finiteresources, reduces environmental impacts, se-cures supplies for the long-term, and fre-quently offers attractive economic returns.However, increasing access to energy servicesreally depends on an enhanced supply. Fortu-nately, this can be safely achieved by using awide variety of renewable sources, some ofwhich, such as hydropower and biomass, arealready well-developed. Most developingcountries are located in tropical areas wherethe existence of rivers and rain-fed, arable landprovide the conditions for these energy sec-tors to flourish. While competition with foodproduction and multiple water uses are im-portant issues, more often than not the prob-lems may be overestimated, and can be dealtwith through appropriate logistical and land-use planning.

countriesdeveloping

energyoptionsRenewable

With global energy consumption set to surge,greenhouse gas emissions increasing, and stocksof fossil fuels dwindling, JOSÉ GOLDEMBERGand OSWALDO LUCON look at the alternatives.

JOSÉ GOLDEMBERG is Professor atthe Institute of Electrotechnics andEnergy, University of São Paulo, Brazil.OSWALDO LUCON is a technicaladviser on energy for the São PauloState Environment Secretariat, Brazil.

in

�

310

300

280

260

240

220

200

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

MakingIt18

Attractive biomass options already exist.Sugar cane ethanol production (and associatedbagasse cogeneration) in Brazil, geothermalenergy in the Philippines, agricultural waste-toenergy in India, thermal solar energy in China,and improved wood-fuel cook stoves in someAfrican countries are some successful examples.

There are also newer renewable technolo-gies under development, with biomass havinggood prospects for rapid technological ad-vances, particularly in relation to improved useof agricultural wastes, municipal solid waste in-cineration, and the production of several typesof biodiesel. Several bioenergy transformationroutes using diverse types of biomass are pos-sible, from simple boilers for domestic heatingto integrated energy farms.

Although still in the research phase, secondgeneration biofuels, and advanced solar, marineand geothermal applications, may become eco-nomically viable in certain circumstances.

Wind and solarWind power production technology hasbecome highly sophisticated, with importantdevelopments in the areas of control, aerody-namics, and materials. Large systems can havehundreds of high-tech, large generators, eachwith a generation capacity of 5MW and bladesspanning more than 80 metres. Wind powermachinery costs have recently dropped signif-icantly, mainly because manufacturers in de-veloped countries have benefited fromgovernment support policies. As a consequence,the price of wind turbines for customers in de-veloping countries is also coming down.

Solar thermal energy has huge potential inthe developing world, but the relatively highstart-up costs, and the subsidies provided toconventional fossil-based sources, are barriersto a more rapid deployment. Simple applica-tions such as plastic solar collectors or cookstoves are initial steps frequently used indemonstration projects, especially in poorercountries. However, their take up has oftenbeen very limited, and the user regularly revertsto traditional sources of energy. More positively,China has moved steps ahead by subsidizingthe use of solar panels for water heating, whilein Brazil, the use of solar panels may negate theneed for large investments in the additionalpower production now required to supply theelectricity used at peak times. For example, solarpower can be used to produce electricity forwater heaters and other small appliances.

For small islands, mountain villages andother more remote communities, solar photo-voltaic systems offer good prospects. The tech-nology is ideal for small applications and certain

niches, as the power produced is enough to re-frigerate vaccines and medicines; preserve foodand fishing products; make small and microbusinesses viable; light houses, schools andmedical centres; extract and pump water fromwells; and power communication and enter-tainment systems. Solar may be one of the maintechnologies for future integration of decen-tralized energy systems.

BiofuelsSo far, bioethanol and biodiesel are the best bio-fuel options, followed in some cases by veg-etable oils. The Brazilian sugarcane ethanolprogramme produces fuel that is cost compet-itive in a free market, and has a positive energybalance of up to ten outputs to one unit of

input. For these reasons alone, it could be pro-moted as a fuel alternative in other countriesin the world. Concerns about the environmen-tal and social impacts of biofuels are being ad-dressed in a responsible manner – a responsedriven by the threat that technical trade barri-ers will be imposed as a result of consumerpressure. Meanwhile, there are high expecta-tions for second-generation biofuels, especiallycellulosic ethanol (produced from wood,grasses, or the non-edible parts of plants),which could promote a real clean energy revo-lution when achieving competitive costs.

DecouplingThe energy crisis of the late 1970s led to anenergy revolution when new technologies thatbecame commercially available at that timemade it possible to provide energy serviceswith a smaller energy input than would havebeen possible with the technologies then inwidespread use. This meant there could be adecoupling between GDP growth and energygrowth, and this did in fact take place in theindustrialized countries in the 1970s and 1980s.Using energy more efficiently, and switchingfrom fossil fuels to renewable energy sources,meant that economic growth, as measured byGDP growth rates, could continue, eventhough the growth in energy consumptionslowed. For example, the energy consumptionof the European Union is today 50% lowerthan it would have been if the measures takenin response to the 1973 oil crisis had not beenimplemented. Another more recent exampleis provided by China, which since 1990 has en-acted bold energy efficiency measures. WhileGDP has increased almost nine-fold, in thesame period, carbon emissions are only twoand half times greater.

In this context, developing countries cantoday take advantage of a great opportunity.Rather than replicating the economic develop-ment process of industrialized nations, whichwent through a phase that was dirty and waste-ful, and created an enormous legacy of envi-ronmental pollution, developing countries canleapfrog ahead by incorporating currently avail-able, modern, and efficient technologies in theearly stages of their development process.

The use of renewable energy resources isprogressing rapidly, and will probably repre-sent a very significant contribution to energyconsumption in the next few decades. A com-bination of energy efficiency, and renewableand emerging new technologies using biomass,wind, and solar energies, could sustain devel-opment for the majority of the human popula-tion over the course of the 21st century. �

� Renewable power capacities, 2008 (REN21, Renewables Global Status

Report: 2009 Update)

Wor

ldD

evel

opin

g co

untri

es

Solar PV (grid)

Geothermal

Biomass

Wind

Small hydro

EU-2

7Ch

ina

Unite

d St

ates

Ger

man

ySp

ain

Indi

aJa

pan

Gigawatts

MakingIt 19

Nearly one-third of global energy demandand almost 40% of worldwide CO2 emissionsare attributable to industrial activities. Thebulk of these CO2 emissions are related tothe large primary materials industries, suchas chemicals and petrochemicals, iron andsteel, cement, pulp and paper, and alu-minium. If we are to successfully combat cli-mate change, industry will need to transformthe way it uses energy, and radically reduceits CO2 emissions.

Over recent decades, industrial energy effi-ciency has improved, and CO2 intensity has de-clined substantially in many sectors. However,this progress has been more than offset bygrowing industrial production worldwide. Asa result, total industrial energy consumptionand CO2 emissions have continued to rise.Over the next 40 years, demand for industrialmaterials in most sectors is expected to double

or triple. Projections of future energy use andemissions based on current technologies showthat without decisive action, these trends willcontinue. This path is not sustainable.

Making substantial cuts in industrial CO2emissions will require the widespread adop-tion of current best available technologies(BAT), and the development and deploymentof a range of new technologies. This technol-ogy transition is urgent; industrial emissionsmust peak in the coming decade if the worstimpacts of climate change are to be avoided.Industry and governments will need to worktogether to research, develop, demonstrate,and deploy the promising new technologiesthat have already been identified, and also to

find and advance new processes that will allowfor the CO2-free production of industrial materials in the longer term.

Furthermore, such emissions reductionswill only be possible if all the regions of theworld contribute. Action in OECD countriesalone, which represent 33% of current globalindustrial CO2 emissions, will not be sufficientto make the necessary reductions. Industrialproduction will continue to grow most stronglyin non-OECD countries so that by 2050, if nofurther action is taken, they will account for80% of global industrial CO2 emissions.

Industry exhibits a number of characteris-tics that set it apart from other end-use sec-tors, and these need to be taken into accountwhen designing energy and climate policiesfor the sector. First, while significant energyefficiency potentials remain, they are smallerthan in the building or transport sectors.

Drawing on the new International Energy Agency publication, EnergyTechnology Transitions for Industry: Strategies for the Next Industrial Revolution,NOBUO TANAKA looks at the technologies for reducing industrial CO2emissions and the policies that are needed to ensure their widespread use.

�

NOBUO TANAKA is theExecutive Director ofthe International EnergyAgency (IEA)

industrialnextThe

revolutionFemale workerengaged in zinc andlead extractionoperations at theMadero mine,Zacatecas, Mexico.

Phot

o: K

eith

Dan

nem

iller

/Cor

bis

MakingIt20

Policies should therefore promote realisticlevels of energy efficiency improvement andCO2 reduction, and ensure, where possible,flexibility in the way these can be achieved. Sec-ondly, many industries compete in global orregional markets, and so the introduction ofpolicies that impose a cost on CO2 emissionsin some regions, but not others, risks damagingcompetitiveness and may lead to carbon leak-age – in other words, industries relocating toregions with lesser carbon restrictions. Whilethere is little, if any, evidence of such effects todate, this may become a significant problem ifCO2 prices rise substantially in the future.Thirdly, many industrial sectors have theknowledge, technology access, and financingpossibilities to reduce their own CO2 emis-sions if governments provide a stable policyframework that will create clear, predictable,long-term economic incentives for the use ofnew efficient and low-carbon technologies.

The implementation of current BAT couldreduce industrial energy use by between 20% and30%, and should be a priority in the short term.But this will be nowhere near enough to achieveabsolute reductions in CO2 emission levels, asproduction is expected to double or triple inmany sectors. Continued improvements inenergy efficiency offer the largest and least ex-pensive way of achieving CO2 savings over theperiod to 2050. Energy efficiency gains will needto increase to 1.3% per year, a rate that will re-quire the development of new energy-efficient technologies. Many new technologieswhich can support such an outcome, for exam-ple smelt reduction, new separation membranes,black liquor and biomass gasification, and ad-vanced cogeneration, are currently being devel-oped, demonstrated, and adopted by industry.

New low-carbon fuels and technologies willalso be needed, with a smaller but importantcontribution from increased recycling andenergy recovery. The use of biomass and elec-tricity as CO2-free energy carriers will be sig-nificant. While the technologies required areoften sector-specific, the development and de-ployment of carbon capture and storage (CCS)will be critical for achieving deep emissionsreductions, particularly in the iron and steel,and cement sectors.

Additional research, development, anddemonstration are needed to develop break-through process technologies that allow forthe CO2-free production of materials, and toadvance understanding of system approaches,such as the optimization of life-cycles throughrecycling and using more efficient materials.These longer-term options will be needed inthe second half of this century to ensure sus-

tainability of industrial processes to the endof the century, and beyond.

Technology development is fraught withuncertainties. Some of the technologies iden-tified may never come to fruition, but futureresearch may also deliver new technologiesor breakthroughs that are not currently fore-seen. A portfolio approach can help to dealwith this uncertainty.

CO2 emissions reductions will be neededacross the whole of industry, but action is par-ticularly crucial in the five most energy-

intensive sectors: iron and steel, cement,chemicals and petrochemicals, pulp and paper,and aluminium. Together, these sectors cur-rently account for 75% of total direct CO2emissions from industry, and the applicationof current BAT, together with the developmentand deployment of promising new technolo-gies, will be required in order to significantlyreduce energy use and CO2 emissions.

Iron and steelThe worldwide use of current BAT could de-liver energy savings of about 20% of today’sconsumption. Given the limited efficiency po-tential inherent in existing technologies, newtechnologies such as smelt reduction will beneeded. Fuel switching can also help to reduceemissions. CCS is an important option thatwould allow the sector to achieve deep reduc-tions in emissions in the future. Large-scaleCO2 capture pilot projects at iron and steelplants must be urgently developed in order tobetter understand the cost and performanceof different CO2 capture methods.

CementReducing CO2 emissions in this sector is verychallenging owing to high process emissionsrelated to the production of clinker, the maincomponent in cement. Improving energy effi-ciency at existing plants, investing in BAT fornew plants, and increasing the use of alterna-tive fuels and clinker substitutes could reducecurrent energy use by 21%, but this will not beenough to achieve net emissions reductions inthe future. New technologies should be devel-oped and implemented, particularly in the ap-plication of CCS to cement production.

Chemicals and petrochemicalsThe full application of best practice technol-ogy in chemical processes could achieveenergy savings of approximately 15%. Addi-tional measures such as process intensifica-tion and process integration, the greater useof combined heat and power, and life-cycle op-timization by recycling and energy recoveryfrom post-consumer plastic waste, could savemore final energy. However, there are impor-tant barriers which constrain the exploitationof this theoretical potential. To achieve futureCO2 emissions reductions in the sector, arange of new technologies must be developed.

Pulp and paperSignificant potential exists in many countriesto increase energy efficiency and reduce CO2emissions in this sector. A transition to cur-rent BAT could save up to 25% of energy used

�

MakingIt 21

today. Reducing emissions in the sector willrequire additional improvements in effi-ciency, fuel switching to biomass, and the in-creased use of combined heat and power.Promising new technologies such as blackliquor gasification, lignin removal, biomassgasification, and CCS, will also be needed toachieve significant emissions reductions.

AluminiumMost of the energy consumed in the alu-minium industry is in the form of electricityused for smelting. The impact of imple-menting BAT is limited, offering the poten-tial to reduce energy use by up to 12%compared with current levels. Important op-tions include reducing heat losses in refiner-ies, improving process controls, and reducingheat losses and the electricity used insmelters. In the longer-term, moving towardsthe use of zero-carbon electricity in smeltersis the single largest opportunity for long-term CO2 emissions reduction.

***The world’s industry emissions in 2050 can

only be reduced by 21% compared to today’slevels (industry’s contribution to a halving ofglobal emissions) if all regions significantlyreduce their CO2 intensity. In a ‘business-as-usual’ scenario, where there is no change inpolicy, emissions are expected to continuerising in all regions to 2050. China’s emissionswill continue to rise rapidly in the next twentyyears, but then will rise only moderately as thecountry’s consumption of the most CO2-in-tensive products, such as cement and iron andsteel, begins to level off after 2030. As domes-tic consumption feeds demand, India’s indus-trial CO2 emissions will grow the most of allcountries. In other developing countries inAsia, Africa, and the Middle East, current levelsof industrial development are significantlybelow current levels, and industrial produc-tion is expected to grow at the fastest rates.These three regions will account for 24% oftotal global industry emissions by 2050, significantly surpassing total OECD industryemissions. If global industry is to achieve significant reductions in emissions, effort willbe required in these regions to reduce theCO2 intensity of industrial production, andthey will need support for technology transferand deployment.

Bringing about the technology transitionneeded to reduce emissions in industry willnot be easy. It will require both a step change inpolicy implementation by governments, andunprecedented investment in best practicesand new technologies by industry. Engaging

developing countries and their industries inthis transition will also be vital, since most ofthe future growth in industrial production, andtherefore CO2 emissions, will happen in coun-tries outside of the OECD region.

Given these considerations, a global systemof emissions trading may eventually be a cru-cial policy instrument for promoting CO2abatement in industry. However, a worldwidecarbon market is unlikely to emerge immedi-ately and so, in the short to medium term, in-ternational agreements covering some of themain energy-intensive sectors might be a prac-tical first step in stimulating the deploymentof new technologies, while addressing con-cerns about competitiveness and carbon leak-age. Meanwhile, national energy efficiency andCO2 policies, involving standards, incentivesand regulatory reform (including the removalof energy price subsidies), which address spe-cific sectors or particular barriers, will continueto be necessary. Gaining public acceptance forcertain new technologies may also be impor-tant to their widespread deployment.

To complement policies that generatemarket pull, many new technologies will needgovernment support while in the research, de-velopment, and demonstration (RD&D)phases before they become commerciallyviable. There is an urgent need for a major ac-celeration of RD&D in breakthrough tech-nologies that have the potential to changeindustrial energy use or reduce greenhousegas emissions. Support for demonstrationprojects will be particularly important. Thiswill require greater international collabora-tion, and will need to include mechanisms tofacilitate the transfer and deployment of low-carbon technologies in developing countries.

A number of regional and internationalindustrial associations are already examininghow their members might rise to the chal-lenge posed by climate change. I welcomethese efforts and reaffirm that the Interna-tional Energy Agency (IEA) is looking to playits part. For instance, the IEA has been askedby the G8 to develop roadmaps for the mostimportant low-carbon technologies. As partof this activity we have recently completed, to-gether with the Cement Sustainability Initia-tive of the World Business Council forSustainable Development, a cement sectorroadmap. We would welcome the opportunityto replicate this activity with other sectors andto help show the way to the next industrialrevolution. Industrial production growthmust be developed in a sustainable way.Countries and industry should make greengrowth their priority. �

“Industry andgovernments will need towork together to research,develop, demonstrate anddeploy the promising newtechnologies that havealready been identified”

Phot

o: B

arna

by C

hand

ler/i

stoc

k

MakingIt22

E N E R G Y

MakingIt 23

Energy access is widely regarded as the ‘missing’Millenium Development Goal. It will create the opportunities for people across the world to step out of the poverty trap.KANDEH K. YUMKELLA andLEENA SRIVASTAVA argue that now is the time to prioritizeenergy access in order to promoteeconomic development.

F O R A L L

MakingIt24

Large parts of humanity – billions of people – live withoutaccess to modern energy services. These are fundamentalservices that most of us take for granted, like light, fuel forheating and cooking, and mechanical power. Despite theefforts of many committed people, working on excellentprogrammes, about 1.5 billion people still don’t have accessto electricity, and around 2.5 billion people rely on traditionalbiomass as their primary source of energy – a clearly unsus-tainable position. It is widely accepted that this lack of accessto affordable, reliable, energy services is a fundamental hin-drance to human, social, and economic development – andis thus a major impediment to achieving the MillenniumDevelopment Goals (MDGs). The issue is also a stark illus-tration of the deep inequity that exists between the rich and

poor. Roughly, the poorer three-quarters of the world’s pop-ulation use only 10% of the world’s energy. The rich coun-tries aim for a secure, environmentally acceptable, andaffordable energy supply – but what about the billions with-out access?

The issue is not abstract for either of us. We have both wit-nessed it in our own countries: Sierra Leone and India. A fewsuccess stories do exist – countries such as China haveimproved the access for their citizens substantially in the lastdecades, but all across sub-Saharan Africa, and in parts ofAsia, people are living without basic energy services. Thedemand for energy in these regions is expected to grow dra-matically, with increases in population and improvementsin living standards adding to the scale of the challenges. It is

Bamako, Mali: Anadult literacy eveningclass illuminated by abulb powered by acar battery.

Phot

o: S

ven

Torfi

nn/P

anos

MakingIt 25

really quite stunning to realize that, if ‘business as usual’ con-ditions are maintained, over the next decades the total num-ber of people without access to modern energy services willnot decrease. Current efforts are insufficient in scale andscope, and attempting to address the issue in the same waythat we have in the past is clearly not remotely adequate.

Energy for developmentEnergy services have an effect on productivity, health, edu-cation, safe water, and communication services. Therefore, itis no surprise that access to energy has a strong correlationto social and economic development indices (e.g. the HumanDevelopment Index, life expectancy at birth, infant mortal-ity rate, maternal mortality, and GDP per capita).

The UN system has been working on energy access issuesfor decades. In 2005, UN-Energy, the UN’s inter-agencymechanism for energy issues, considered the link betweenenergy and the MDGs, and reminded us that: �Energy services, such as lighting, heating, cooking, motivepower, mechanical power, transport and telecommunica-tions, are essential for socio-economic development, sincethey yield social benefits, and support income and employ-ment generation.� Reforms to the energy sector should protect the poor,especially the 1.1 billion people who live on less than US$1per day, and should take gender inequalities into account byrecognizing that the majority of the poor are women.

In 2007, the UNDP reviewed a large number of nationalMDG reports to assess the extent to which energy issueswere included. The findings revealed the need for a morecoherent and focused approach to energy in the 2010 MDGreview process. For example:�About a quarter of the reports offered considerable cov-erage of energy issues, including a more nuanced analysis ofthe country’s energy situation, but about one-third of thereports only had a moderate amount of information on�

“Energy access must moveup the political anddevelopment agendas tobecome a central priority”

KANDEH K. YUMKELLA is theDirector-General of the UnitedNations Industrial DevelopmentOrganization. Since August 2007, hehas served as Chair of UN-Energy,the inter-agency mechanism tocoordinate energy-related issueswithin the UN system. He is also Chair of UNSecretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s Advisory Group onEnergy and Climate Change consisting of businessleaders and experts.

LEENA SRIVASTAVA is the ExecutiveDirector of The Energy andResources Institute (TERI), anindependent, not-for-profit,research institution, based in NewDelhi, and working in the areas ofenergy, environment, and

sustainable development. She was the lead authorfor the Third Assessment Report of theIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

MakingIt26

energy (i.e. a paragraph or more, offering some statisticsor baseline energy information), and some 42% of reportscontained little or no mention of energy at all.� The most popular energy topics discussed were energyefficiency and energy use as a contributor to air pollution.The reports from African countries, however, most often dis-cussed energy in the context of wood-fuel use and defor-estation issues.

The obstacles to energy access are well known. These bar-riers, while complex, can be overcome, and internationalcooperation can help this process. What cannot be over-stressed is that there are no fundamental technical barriers:we know how to build power systems, we know how todesign good cooking stoves, and we know how to meetenergy demand efficiently. What is required is a political pri-oritization. Energy access must move up the political anddevelopment agendas to become a central priority.

Equally important is a clear understanding that localcommunities must be deeply involved in the planning, exe-cution, and end-use of energy services. Energy access inter-ventions must be guided by an awareness of local commu-nities’ unique situations and needs.

Getting business on boardThe bulk of the efforts to improve energy access have, natu-rally, focused on parts of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Thereare decades of experience with many poorly designed orimplemented programmes, but some successful modelshave emerged, including both public efforts such as thosecarried out by the international financial institutions andUN agencies, and the delivery of related funding and servicesby NGOs and private sector companies, such as India’s SolarElectric Light Company.

Many global campaigns are also starting to address theissue. One of these is the Lighting a Billion Lives campaignwhich aims to bring light into the lives of one billion ruralpeople by replacing kerosene and paraffin lanterns withsolar lanterns. This campaign, which was launched in

FIGURE 1: Countries with energy access targets (UNDP, 2009)

All developing countries (total number of countries: 140)

Electricity 68Modern fuels 16

Improved cooking stoves 11Mechanical power 5

Modern fuels 12Improved cooking stoves 7

Mechanical power 5

Sub-Saharan Africa (total number of countries: 45)