Conventional 3D staging PET/CT in CT simulation for lung ...

Lung Cancer Staging: An Overview of the New Staging System and Implications for Radiographic...

-

Upload

joshua-carson -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Lung Cancer Staging: An Overview of the New Staging System and Implications for Radiographic...

da1(oecimnttt

1Lccttdi

Lung Cancer Staging: AnOverview of the New Staging System andImplications for Radiographic Clinical StagingJoshua Carson, MD, and David J. Finley, MD

wSc

cuttwM2Amgt

The Cancer Commission of the League of Nations HealthOrganization established the Radiological Sub-Commis-

sion in 1929 with the primary mandate of creating a commoncancer staging system to facilitate effective communicationacross institutions around the world. Shortly thereafter, DrPierre Denoix developed the tumor-nodes-metastases (TNM)system used in almost all solid cancer staging today, and hecontinued to broaden and refine his TNM-based staging ap-proach through a series of articles published in the 1940s and1950s.1 Denoix’s approach gained its first institutional en-

orsement when the 7th International Congress of Radiologydopted TNM staging for laryngeal and breast cancer in953. Subsequently, as chair of the Union Contre Le CancerUICC) staging committee, Denoix oversaw the publicationf a series of “fascicles” (brochures) released during the 1960sstablishing standardized TNM staging for 23 solid organancers. A tradition of international consensus in cancer stag-ng was established in 1969, when the American Joint Com-

ittee for Cancer Staging and End Results Reporting (re-amed American Joint Committee on Cancer in 1980) andhe UICC agreed that all subsequent staging recommenda-ions by either body would be published in consultation withhe other.2

Lung cancer staging was incorporated into the UICC TNMstaging system in 1966. The first substantial revision of thelung cancer TNM staging was proposed by Mountain et al3 in

973 with the publication of “A Clinical Staging System forung Cancer.” This work was based on the outcomes of 2155ases of lung cancer, 1712 of which were nonsmall cell lungancer (NSCLC). It further specified the T, N, and M descrip-ors and introduced stage groupings for the first time. Duringhe next 25 years, the lung cancer TNM staging system un-erwent 3 major revisions, all based on Dr Mountain’s grow-

ng database, which had increased to 5319 cases by 1996.4 It

Thoracic Surgery Division, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, NewYork, NY.

Address reprint requests to David J. Finley, MD, Thoracic Surgery Division,Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York,

NY 10065. E-mail: [email protected]0037-198X/11/$-see front matter © 2011 Published by Elsevier Inc.doi:10.1053/j.ro.2011.02.004

as at this point that the International Association for thetudy of Lung Cancer (IASLC) initiated the IASLC Lung Can-er Staging Project.

The IASLC Lung Staging Project sought to revise lung can-er staging by using a data set more powerful, current, andniversal than any single institutional database. From 1997o 2009, this group developed a database incorporating pa-ient data gathered from participating institutions around theorld, collecting more than 81,000 cases of lung cancer.ost cases were from Europe and the United States (58% and

1%, respectively), but a significant number of patients fromsia and Australia were included. Patients treated with allodalities were accepted into the database (including sur-

ery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy) to better samplehe true lung cancer population.2

The 7th edition of the lung cancer staging system thusrepresents the culmination of a remarkably comprehensivereview process. Improvements in surgical, medical and radi-ation treatments, surveillance, radiographic staging, postop-erative care, and minimally invasive surgery have all changedlung cancer treatment and survival in the last decade. Thesenew factors have not been accounted for in the previousstaging schema and impact treatment decisions. On the basisof outcomes data from patients treated with these improvedmodalities, the TNM staging is more representative of currenttreatment patterns and helps better guide the clinician. TheIASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project set out to accomplish aseries of goals:

1. Aid the clinician in planning treatment.2. Provide some indication of prognosis for each stage.3. Assist in the evaluation of the results of treatment.4. Facilitate the exchange of information between centers

across the globe5. To contribute to the continuing investigation of human

cancer.2

This article will review the AJCC 7th edition Cancer Stagingfor lung cancer and will compare it with the 6th edition, withemphasis on operable disease. Clinical staging, its strengths

and weakness, along with minimally invasive staging supple-187

at�7Tlm3s

6

188 J. Carson and D.J. Finley

ments will be discussed to aid the clinician in the preopera-tive staging of lung cancer.

TNM Staging ChangesNew to the 7th EditionOverview of ChangesThe 7th edition of the TNM Classification of Malignant Tu-mors contains the first revision to lung staging since the pub-lication of the 5th edition in 1997. (The 6th edition carriedno revisions for lung cancer.) These revisions were deter-mined entirely by the recommendations of the IASLC andreflect outcomes data on 68,463 cases of NSCLC and 13,032cases of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) gathered from aroundthe world (with a numerical bias towards Europe).

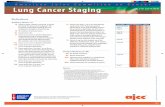

The 7th edition introduces further subdivision of the T andM stages, dividing the T1, T2 and M1 into substages (Table1). These changes were intended to better reflect an increasedappreciation for the subtle prognostic differences associatedwith specific aspects of primary and metastatic disease pro-gression.

Nodal substages were not revised, but the definitions ofvarious nodal levels are clarified, resolving discrepancies be-tween the various nodal maps in common use. Furthermore,though not applied to the current edition, the IASLC outlinesa new system for grouping mediastinal lymph nodes intoanatomic zones, with the recommendation that these zonesbe considered for future study.

Tumor Descriptor ChangesTumor Size and SubdivisionFurther stratification of tumor staging by size is one of thecentral changes found in the 7th edition. What were previ-ously considered T1 and T2 tumors were further divided by

Table 1 T and M Descriptor: Summary of Changes from theth Edition

SixthEdition Qualifying Descriptors

SeventhEdition

T1 Tumors <2 cm T1aTumors >2 cm and <3 cm T1b

T2 Tumors <5 cm T2aTumors >5 cm >7 cm T2bTumors >7 cm T3

[Any T3 tumor in 6th Ed remains T3]T4 Separate nodule(s) in same lobe T3

Malignant pleural or pericardialeffusion

M1a

M1 Satellite nodules in separate lobe ofipsilateral lung

T4

Additional nodules in contralateral lung M1aPleural nodules M1aDistant metastases M1b

This table lists all the substages from the 6th edition effect by the 7thedition revisions and summarizes the new or revised descriptorsfor classification.

size, creating subcategories T1a, T1b, T2a, and T2b. Al-

though all tumors smaller than 3 cm in greatest dimensionare still T1, they are further subdivided such that tumors�2cm are now T1a, and those which are �2 cm (up to 3 cm)re considered T1b. Likewise, T2a is now used to designateumors �3 cm but �5 cm in size, and T2b denotes tumors

3 cm and up to 7 cm. Furthermore, tumors larger thancm are now considered at least T3 by virtue of size alone.hese specific size cut-offs were selected on the basis of a

og-rank analysis of 4891 resected (RO) tumors with docu-ented pathologic assessment of size, which identified 2 cm,cm, 5 cm, and 7 cm as the optimal cut off points for

egregating patients by survival (Tables 2 and 3).5

Multifocal TumorsThe seventh edition also redefines the staging impact of mul-tifocal disease, as the outcomes of patients with certain pat-terns of satellite lesions were found to be better than previ-ously thought.6–9 Multiple tumors of similar histology in thesame lobe are now T3 instead of T4 (provided that none ofthe individual lesions meets T4 criteria on its own). Likewise,patients with histologically similar tumor nodules found inseparate lobes of the same (ipsilateral) lung are now staged asT4 (previously M1). Histologically, similar nodules in thecontralateral lung are still considered M1 disease (Tables 1and 2).

Multifocal lesions or satellite nodules should not be con-fused with synchronous primary tumors. Multifocal diseaseis defined as such only when histology suggests the variouslesions represent a single disease process. Two nodules show-ing distinct histopathologies are considered synchronous pri-maries–two separate disease processes that are occurring inthe same patient. As such, in cases of synchronous primaries,both primary tumors should be staged separately and thestage of the patient is the highest stage lesion.10

Pleural Invasion and Malignant EffusionAs in the previous system, invasion of visceral pleura conveysa minimum tumor stage of T2, and involvement of the me-diastinal or parietal pleura qualifies as T3 disease. A clearpathologic definition of pleural invasion was provided, out-

Table 2 T Staging Changes Correlate with Survival

Tumor DescriptorsSeventhEdition

5-YearSurviva1, %

Tumors <2 cm T1a 77Tumors <3 cm T1b 71Tumors <5 cm T2a 58Tumors >5 cm >7 cm T2b 49Tumors >7 cm T3 35Same lobe nodules T3 28Separate nodule(s) in

ipsilateral lungT4 22

Malignant pleural orpericardial effusion

M1a 2

T-staging changes correlate with survival. Subdivision of tumor basedon size separated T1 and T2 into 2 subcategories each. T3 lesionsrepresented large tumors or multiple nodules in the same lobe.Multiple nodules in the ipsilateral lung are now considered T4 and

all malignant pleural or pericardial disease was upgraded to M1a.

he(

NIlmzdm

tf

TTT

Lung cancer staging 189

lining the use of elastin stains.11 The 7th edition also providesa new system of histologic grading of pleural invasion, butthis “PL” substaging system is provided expressly for researchpurposes, and is not currently factored into staging. Finally,because of remarkably poor prognosis of patients with posi-tive cytology from pleural or pericardial fluid, malignantpleural and pericardial effusions now qualify as M1a dis-ease.12

Nodal DescriptorsThe 7th edition does not change the nodal staging criteria perse, but it does clarify precise definitions of the various nodallevels, and it proposes a new model for nodal zones to facil-

Table 3 T Descriptors Overview

TX Primary tumor confirmed, but stage cannot bedetermined (eg, tumor undetectable on imagingand diagnostics despite positive sputumcytology)

0 No evidence of a primary tumoris Carcinoma in-situ1 Tumor <3 cm in greatest dimension and meets the

following criteria:Tumor is surrounded by lung or visceral pleuraThere is no evidence main bronchus invasion

T1a tumor <2 cmT1b 2 cm < Tumor <3 cm

T2 3 cm < tumor <7 cm or meets any of thefollowing criteria:

Tumor involves main bronchus (>2 cm fromcarina)

Tumor invades visceral pleura, but no furtherTumor associated with atelectasis or obstructive

pneumonitis extending to hilar region but notinvolving the entire lung

T2a 3 cm < tumor <5 cmT2b 5 cm < tumor <7 cm

T3 Tumor >7 cm in greatest dimension or meets anyof the following criteria:

Directly invades chest wall, diaphragm, phrenicnerve, mediastinal pleura or parietalpericardium

Tumor involves main bronchus less than 2 cmfrom (but not into) carina

Associated with atelectasis or obstructivepneumonitis of entire lung

Associated with satellite nodule or nodules thatare all limited to the same lobe as main tumor

T4 Tumor of any size that meets any of the followingcriteria:

Invades mediastinum, heart, great vessels,trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve, esophagus,vertebral body

Involves the carinaAssociated with satellite nodule or nodules in an

ipsilateral lobe separate from that containingthe primary

itate future study.

New International Lymph Node MapThough no changes were made to the lymph node descrip-tors in the 7th edition, a new lymph node map was created toresolve differences between the American Thoracic Societymap (Mountain-Dresler’s) and the Japan Lung Cancer Soci-ety map (Naruke’s).13 These changes were minimal but

elped create a consistent nomenclature to be used, allowingasier comparison between different international centersFig. 1).

odal Zonesn addition to consolidating the various nomenclatures forymph node mapping, the 7th edition also introduces a new

ethod which groups the mediastinal nodes into 5 differentones (Table 4). These zones represent areas of similar nodalrainage, and it is thought that defining nodal status by zonesay allow for more prognostically precise nodal staging.14–18

Although the committee falls short of incorporating the nodalzones into the subdivision of nodal metastasis (ie, N1a orN1b), studies are underway to confirm their prognosticvalue, and they are expected to play an increased role intreatment decisions.

Metastasis Descriptor ChangesThe M descriptor was also subdivided in an effort to differ-entiate between distant and intrathoracic metastasis. Malig-nant pleural and pericardial effusions, previously consideredT4 disease, are now designated M1a. Contralateral nodulesare also placed in the M1a category. All distant metastaticdisease is considered M1b (Table 1).19

Staging ChangesOverall, the greatest effects of the 7th edition revisions onoverall stage are found in the earlier stages (Ia-IIb), where thesubdivision of tumor descriptors has the largest impact.These changes have been outlined in Table 5.20

Clinical StagingAssessment of Tumor StageComputed tomography (CT) scan continues to provide anexcellent noninvasive and relatively inexpensive modality forassessing tumor size. The impact of pretreatment tumor-sizemeasurements is greater than before as the new system em-phasizes stage segregation based on tumor size, both in thecreation of the T1a/b and T2a/b subdivisions, as well as in thefact that tumors can now be upstaged to T3 by size alone.Preoperative assessment of size is also helpful in anticipatingnodal disease, as increased tumor size has been shown toincrease the risk of nodal disease.15–18

When there is reason to suspect local invasion or criticalanatomic risk factors (ie, carinal proximity), supplementalimaging may be helpful. CT imaging is remarkably inconsis-tent in identifying chest wall invasion.21,22 Although conven-ional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) failed to outper-orm CT in the detection of chest wall invasion,23 the authors

of small-scale trials have found both respiratory dynamic

auidmdat

s

lor ver

190 J. Carson and D.J. Finley

MRI and transthoracic ultrasonography achieved improvedaccuracy in assessing chest wall invasion. The best imagingmodality to determine chest wall invasion remains in ques-tion, but as imaging technology and practice continues toevolve, it is likely that various modalities will soon offer pre-cise and accurate noninvasive assessments to inform criticalpretreatment planning.

Local invasion of mediastinal structures can also be dif-ficult to determine radiographically. Although gross inva-sion can be obvious, CT images are unreliable for differ-

Figure 1 IASLC nodal chart. Reprinted with permission cCancer. Copyright © 2008 Aletta Ann Frazier, MD. (Co

entiating abutment from subtle invasion.23,24 Although the v

ddition of endobronchial ultrasound and/or esophagealltrasound (EBUS and/or EUS) can sometimes be helpful

n questionable cases, in the setting of otherwise operableisease, anything short of obvious extensive local invasionust be confirmed intraoperatively.25 Likewise, precise

efinition of an airway lesion’s proximity to the carinand/or main bronchi requires bronchoscopic confirma-ion.

Although it may not provide a reliable evaluation of T-tage, high-resolution CT remains an invaluable asset for pro-

y of the International Association for the Study of Lungsion of the figure is available online.)

ourtes

iding the detailed anatomic information required for plan-

Csn

Lung cancer staging 191

ning an operative approach and is currently the imagingmodality of choice.

Assessment of Nodal StageBy far, the most complicated and rapidly evolving aspect ofclinical staging for NSCLC is the question of how to bestassess nodal status. CT scan alone has long been recognizedas ineffective as a stand-alone test for assessing mediastinaland hilar lymph nodes in NSCLC patients, with false negativerates reported as high as 30%.26 Although more sensitive than

T, fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET)cans have also been found to miss 6%-20% of cases withodal disease,27–29 particularly in the setting of larger primary

tumors and in the assessment of hilar nodes.28 Such false-negative results are particularly concerning for patients beingconsidered for definitive radiation therapy for early stagelung cancers; as failing to recognize nodal disease can resultin inadequate treatment. Because a negative CT/PET scandoes not obviate the need for tissue sampling, our bias is toconfirm negative hilar nodal involvement with EBUS-TBNA(ie, endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspira-tion). Likewise, positive nodal disease suggested by CT/PET

Table 4 Nodal Zones

Nodal Zone D

Supraclavicular zone Low cervical, supraUpper zone Upper paratrachea

Prevascular/retrotrLower paratrachea

AP zone Subaortic/para-aorSubcarinal zone SubcarinalLower zone Paraesophageal

Pulmonary ligamenHilar/interlobar zone Hilar

InterlobarPeripheral zone Lobar

SegmentalSubsegmental

Nodal draining basins are the basis for this grouping of the nodal stAP, aortopulmonary.

Table 5 Changes from the 6th Edition Staging Group

6th Edition 7th Edition

T1 (�2 cm) T1aT1 (>2 cm � 3 cm) T1bT2 (>3 cm � 5 cm) T2aT2 (>5 cm � 7 cm) T2bT2 (>7 cm) T3T3 (direct invasion)T4 (same lobe nodules)T4 (extension) T4M1 (ipsilateral nodules)T4 (pleural effusion) M1aM1 (contralateral nodules)M1 (distant) M1b

*Stage groups that are asterisked are the changes seen between th

same lung and ipsilateral lung were downstaged, and all malignant effmust be confirmed histologically because of the risk of false-positive results. Beyond their immediate diagnostic role,these studies are remarkably helpful in planning tissue sam-pling procedures, likely augmenting their accuracy.

Nodal staging algorithms are in flux with the increasinguse of endobronchial and esophageal ultrasound-guided bi-opsy techniques (EUS-FNA). Quite recently, preoperativemediastinoscopy was the standard of care in the workup formost resection candidates; recently, its role has diminishedwith the increasing availability of high-quality CT/PET aswell as the more widespread use of EBUS-TBNA/EUS-FNAcapabilities. EBUS-TBNA/EUS-FNA provides a minimally in-vasive and remarkably sensitive modality for confirmingnodal disease identified on CT/PET imaging.25

Meyers et al28 found that adding mediastinoscopy to pa-tients without evidence of mediastinal nodal disease on CT/PET scans lowered the false-negative rate by only 1%, ren-dering its use not cost-effective. Conversely, Herth et al30

found that a negative EBUS-TBNA result in patients withnegative CT/PET imaging carried a negative predictive valueof 99% when using a technique that is both less invasive andless expensive than mediastinoscopy. At our institution, a

ptor Nodal Station

ular and sternal notch 1 R and 1 L2 R and 2 L

l 3a and 3p4 R and 4 L5 and 678 R and 8 L9 R and 9 L10 R and 10 L11 R and 11 L12 R and 12 L13 R and 13 L14 R and 14 L

and will require future validation to assess prognostic significance.

N0 N1 N2 N3

IA IIA IIIA IIIBIA IIA IIIA IIIBIB IIA* IIIA IIIBIIA* IIB IIIA IIIBIIB* IIIA* IIIA IIIBIIB IIIA IIIA IIIBIIB* IIIA* IIIA* IIIBIIIA* IIIA* IIIB IIIBIIIA* IIIA* IIIB* IIIB*IV* IV* IV* IV*IV IV IV IVIV IV IV IV

nd 7th editions. Larger tumors were upstaged, multiple nodules in

escri

claviclachealtic

t

ations

e 6th a

usions were upstaged.

192 J. Carson and D.J. Finley

negative CT/PET is considered adequate preoperative assess-ment of the mediastinum, except for patients who may re-quire a pneumonectomy. Negative CT/PET for assessment ofhilar disease, followed by a negative EBUS-TBNA, is consid-ered adequate workup to proceed to surgical resection with-out neoadjuvant therapy. It is worth noting, however, thatthis is not to imply that negative findings on a CT/PET scanfollowed by a negative EBUS-TBNA can be taken as proof-positive confirmation of N0 status, but it is currently the bestminimally invasive approach to stage these patients.

In years past, it was held by many that a negative EBUS-TBNA in the setting of positive CT/PET findings requiredconfirmatory with mediastinoscopy.31 Recently, others havefound that improved EBUS-TBNA sensitivity limit the mar-ginal utility of such confirmatory mediastinoscopies. In amulticenter randomized control trial, Annema et al32 foundthat even in patients with suspicious CT/PET findings, per-forming mediastinoscopy after a negative EBUS/EUS-TBNAonly detected nodal disease in 9% of those patients. Thisfinding suggests 11 mediastinoscopies would be necessary todetect a single case of EBUS/EUS-occult nodal disease. Assuch, we do not routinely perform mediastinoscopies in pa-tients who are CT/PET positive but EBUS negative for nodaldisease. In addition, avoiding a pretreatment mediastinos-copy has the added benefit of preserving the feasibility ofmediastinoscopy for posttreatment restaging. However, asalways, individual practices must be adjusted to reflect thetechnology and expertise of any treatment setting.

ConclusionsThe 7th edition lung cancer TNM staging system’s changesare significant for many reasons, including that this is the firsttime diverse international data were used. In addition, almost20 times the number of patients were reviewed to make therecommendations for this edition, including patients whoreceived a wide variety of treatment modalities. Specificchanges to the T and M descriptors with stage shift are themajor differences and reflect the overall survival of thesesubgroups. The revisions made from the previous systemwere carefully selected to improve prognostic precision andaccuracy of lung cancer staging.

References1. Denoix P: The TNM Staging System. Bull Inst Natl Hyg 7:743, 19522. Goldstraw P: Staging Manual in Thoracic Oncology. Orange Park, FL,

Editorial Rx Publishing Group, 2009, p 1633. Mountain CF, Carr DT, Anderson WA: A system for the clinical staging

of lung cancer. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 120:130-138,1974

4. Mountain CF: Revisions in the International System for Staging LungCancer. Chest 111:1710-1717, 1997

5. Rami-Porta R, Ball D, Crowley J, et al: The IASLC Lung Cancer StagingProject: Proposals for the revision of the T descriptors in the forthcom-ing (seventh) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J ThoracOncol 2:593-602, 2007

6. Aokage K, Ishii G, Nagai K, et al: Intrapulmonary metastasis in resectedpathologic stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer: Possible contributionof aerogenous metastasis to the favorable outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc

Surg 134:386-391, 20077. Battafarano RJ, Meyers BF, Guthrie TJ, et al: Surgical resection of mul-tifocal non-small cell lung cancer is associated with prolonged survival.Ann Thorac Surg 74:988-993, 2002; discussion: 993-994

8. Gallo AE, Donington JS: The role of surgery in the treatment of stage IIInon-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 9:247-254, 2007

9. Roy MS, Donington JS: Management of locally advanced nonsmall celllung cancer from a surgical perspective. Curr Treat Options Oncol8:1-14, 2007

10. Finley DJ, Yoshizawa A, Travis W, et al: Predictors of outcomes aftersurgical treatment of synchronous primary lung cancers. J Thorac On-col 5:197-205, 2010

11. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Rami-Porta R, et al: Visceral pleural invasion:Pathologic criteria and use of elastic stains: Proposal for the 7th editionof the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 3:1384-1390,2008

12. Jett JR, Schild SE, Keith RL, et al: Treatment of non-small cell lungcancer, stage IIIB: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines(2nd edition). Chest 132:266S-276S, 2007

13. Rusch VW, Asamura H, Watanabe H, et al: The IASLC lung cancerstaging project: A proposal for a new international lymph node map inthe forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lungcancer. J Thorac Oncol 4:568-577, 2009

14. Rusch VW, Crowley J, Giroux DJ, et al: The IASLC Lung Cancer StagingProject: Proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcom-ing seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J ThoracOncol 2:603-612, 2007

15. Ikeda N, Maeda J, Yashima K, et al: A clinicopathological study ofresected adenocarcinoma 2 cm or less in diameter. Ann Thorac Surg78:1011-1016, 2004

16. Miller DL, Rowland CM, Deschamps C, et al: Surgical treatment ofnon-small cell lung cancer 1 cm or less in diameter. Ann Thorac Surg73:1545-1550, 2002 discussion: 1550-1551

17. Rusch VW: Mediastinoscopy: An endangered species? J Clin Oncol23:8283-8285, 2005

18. Takizawa T, Terashima M, Koike T, et al: Lymph node metastasis insmall peripheral adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg116:276-280, 1998

19. Postmus PE, Brambilla E, Chansky K, et al: The IASLC Lung CancerStaging Project: Proposals for revision of the M descriptors in the forth-coming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer.J Thorac Oncol 2:686-693, 2007

20. Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al: The IASLC Lung CancerStaging Project: Proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupingsin the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of ma-lignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol 2:706-714, 2007

21. Bandi V, Lunn W, Ernst A, et al: Ultrasound vs. CT in detecting chestwall invasion by tumor: A prospective study. Chest 133:881-886, 2008

22. Pennes DR, Glazer GM, Wimbish KJ, et al: Chest wall invasion by lungcancer: Limitations of CT evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 144:507-511, 1985

23. Webb WR, Gatsonis C, Zerhouni EA, et al: CT and MR imaging instaging non-small cell bronchogenic carcinoma: Report of the Radio-logic Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology 178:705-713, 1991

24. Glazer HS, Duncan-Meyer J, Aronberg DJ, et al: Pleural and chest wallinvasion in bronchogenic carcinoma: CT evaluation. Radiology 157:191-194, 1985

25. Annema JT, Versteegh MI, Veselic M, et al: Endoscopic ultrasoundadded to mediastinoscopy for preoperative staging of patients with lungcancer. JAMA 294:931-936, 2005

26. Choi YS, Shim YM, Kim J, et al: Mediastinoscopy in patients withclinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 75:364-366, 2003

27. Al Sarraf MD, El Hariry I: The role of induction chemotherapy in thetreatment of patients with locally advanced head and neck cancers: Areview. Gulf J Oncolog Jul:8-18, 2008

28. Meyers BF, Haddad F, Siegel BA, et al: Cost-effectiveness of routinemediastinoscopy in computed tomography- and positron emission to-mography-screened patients with stage I lung cancer. J Thorac Cardio-

vasc Surg 131:822-829, 2006; discussion: 822-829

Lung cancer staging 193

29. Turkmen C, Sonmezoglu K, Toker A, et al: The additional value ofFDG PET imaging for distinguishing N0 or N1 from N2 stage inpreoperative staging of non-small cell lung cancer in region wherethe prevalence of inflammatory lung disease is high. Clin Nucl Med32:607-612, 2007

30. Herth FJ, Eberhardt R, Krasnik M, et al: Endobronchial ultra-sound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of lymph nodes

in the radiologically and positron emission tomography-normalmediastinum in patients with lung cancer. Chest 133:887-891,2008

31. Rintoul RC, Tournoy KG, El Daly H, et al: EBUS-TBNA for the clarifi-cation of PET positive intra-thoracic lymph nodes-an internationalmulti-centre experience. J Thorac Oncol 4:44-48, 2009

32. Annema JT, Bohoslavsky R, Burgers S, et al: Implementation of endo-scopic ultrasound for lung cancer staging. Gastrointest Endosc 71:64-

70:70, 2010