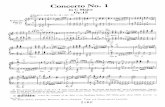

Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor...

Transcript of Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor...

26 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ www.rvsymphony.org

Program Notes By Mark Eliot Jacobs

Ludwig van BeethovenPiano Concerto No. 3 in C minor (1799–1803)

Instrumentation: solo piano with two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bas-soons, horns, and trumpets, with timpani and strings

Duration: about 34 minutes

Beethoven moved from Bonn to Vienna in 1792 in part to study with the great Franz Joseph Haydn. The young Beethoven learned

much about the craft of composition from Haydn, but his experience with the music of Mozart was truly inspirational to him. It was from Mozart that he learned the most about melody and phrasing, the liv-ing breath of classical composition. Mozart’s brooding C minor piano concerto K. 491, completed in 1786, is a completely classical work in every way, but it nevertheless points the way to something new in music. Beethoven found inspiration in K. 491 for continuing this new way of music. It is not overstating things to conclude that the Mozart

Tickets 541-708-6400 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ 27

C minor concerto helped to seed the development of the romantic era of composition before it even began with the music of Beethoven. The Beethoven C minor concerto shows a definite relationship in melody and phrasing to its Mozartian C minor predecessor. The two compositions draw breath from the same atmosphere.

Beethoven’s third piano concerto is the only one of his piano con-certos in minor key. C minor was the key of much of Beethoven’s most important works: the Fifth Symphony and the Pathétique piano sonata among others. Beethoven was the soloist at the premiere in Vi-enna in 1803. His page turner for the occasion, Ignaz Xaver von Sey-fried, later reported that the pages of the manuscript were complete-ly empty expect for some idiosyncratic scrawls that only Beethoven could comprehend. It was the first concerto in the genre to espouse symphonic dimensions. This was made possible in part by advances in piano construction. The new instruments could be played louder and softer, making them a fitting partner to the growing symphonic orchestra. This concerto marked the beginning of the move from the salon to the concert hall.

Hector BerliozEpisode in the Life of an Artist,

Symphonie fantastique (1830)Original instrumentation: 2 flutes (second doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (sec-

ond doubling English horn), 2 clarinets (first doubling E-flat clarinet), 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 cornets, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, 2 ophicleides, timpani, bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, bells (or “one or more pia-nos”), 2 harps, and strings.

Duration: about 52 minutes

One of the major features of this remarkable first symphony is the use of an idée fixe or theme to represent the artist’s unattainable

love for one of several women. One might think of the symphony as a movie before the invention of movies. The program of the work pro-gresses through five scenes outlined in the composer’s own words below.

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) was a serious but not somber artist. He personally identified with characters in then-contemporary ro-mantic fiction and poetry. One work that particularly resonated with him was the idyllic romance Estelle at Nemorin (1788) by Jean Florian. Berlioz found it in his father’s library and “secretly read and re-read it

28 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ www.rvsymphony.org

hundreds of times.” (From Berlioz’s Memoires published posthumous-ly in 1870.)

Berlioz fell in love at first sight on several occasions. One of the first was at age twelve while visiting his grandfather with his family in the French countryside. The object of this early affection was the eighteen-year old niece of a neighbor, one Estelle Duboeuf. The young woman having the same name as the heroine of his favorite book was not lost on the young Berlioz. Again, from the Memoirs: “The moment I beheld her, I was conscious of an electric shock: I loved her. From then on I lived in a daze. I hoped for nothing, I knew nothing, yet my heart felt weighed down by an immense sadness.” The affair, such as it was, was brief, but at age 30 the composer attempted to see her again, believing that he was still in love with her. His persistence did not bear fruit until 1864, when, at age 60, he did have a romantic reunion with Estelle who sustained him in his final days up to his death in 1869.

In September of 1827, Berlioz attended an English language per-formance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Paris. He fell hopelessly in love with the actor portraying Ophelia, Harriet Smithson. It is telling to note that Berlioz didn’t speak a word of English at the time. Berlioz sent her several love letters, all of which went unanswered.

His unrequited love first for Estelle and then for Harriet inspired Berlioz to complete the Symphonie fantastique in 1830. The work was revised in 1845 and again in 1855. Some of the melodic material (in-cluding the famous idée fixe) was taken from material he created while infatuated with Estelle. Undoubtedly, his major inspiration with his current unrequited love for Harriet. The work was premiered in 1830 with Harriet not in attendance. When she eventually heard the work

Tickets 541-708-6400 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ 29

and recognized the composer’s ge-nius, she became open to his ad-vances. Berlioz eventually married Harriet in 1833, but their marriage ended in bitter separation after a short time of unhappiness.

Following are Berlioz’s own pro-gram notes published in the 1845 edition of the score.

Note. The composer’s intention has been to develop, insofar as they contain musical possibil-ities, various situations in the life of an artist. The outline of the instrumental drama, which lacks the help of words, needs to be explained in advance. The following program should thus be considered as the spoken text of an opera, serving to introduce the musical movements, whose character and expression it motivates. The distribution of this program to the audience, at concerts where this sym-phony is to be performed, is indispensable for a complete un-derstanding of the dramatic outline of the work.

Part One. Rêveries, Passions. (Dreams—Passions) The au-thor imagines that a young musician, afflicted with that moral disease that a well-known writer calls the vague des passions, sees for the first time a woman who embodies all the charms of the ideal being he has imagined in his dreams, and he falls desperately in love with her. Through an odd whim, whenever the beloved image appears before the mind’s eye of the artist, it is linked with a musical thought whose character, passionate but at the same time noble and shy, he finds similar to the one he attributes to his beloved.

This melodic image and the model it reflects pursue him incessantly like a double idée fixe. That is the reason for the constant appearance, in every movement of the symphony, of the melody that begins the first Allegro. The passage from this state of melancholy reverie, interrupted by a few fits of groundless joy, to one of frenzied passion, with its gestures of fury, of jealousy, its return of tenderness, its tears, its religious

30 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ www.rvsymphony.org

consolations—this is the subject of the first movement.Part Two. Un bal. (A Ball) The artist finds himself in the

most varied situations—in the midst of the tumult of a party, in the peaceful contemplation of the beauties of nature; but everywhere, in town, in the country, the beloved image ap-pears before him and disturbs his peace of mind.

Part Three. Scène aux champs. (A Scene in the Country) Finding himself one evening in the country, he hears in the distance two shepherds piping a ranz des vaches in dialogue. [A ranz des vaches is a simple signaling melody used to communi-cate at a distance. It is traditionally played on alphorns, but in the symphony on oboe and English horn.] This pastoral duet, the scenery, the quiet rustling of the trees gently brushed by the wind, the hopes he has recently found some reason to entertain—all concur in affording his heart an unaccustomed calm and in giving a more cheerful color to his ideas. He re-flects upon his isolation; he hopes that his loneliness will soon be over. —But what if she were deceiving him! —This min-gling of hope and fear, these ideas of happiness disturbed by

Tickets 541-708-6400 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ 31

black presentiments, form the subject of the Adagio. At the end, one of the shepherds again takes up the ranz des vach-es; the other no longer replies. —Distant sound of thunder—loneliness—silence.

Part Four. Marche au supplice. (March to the Scaffold) Con-vinced that his love is unappreciated, the artist poisons him-self with opium. The dose of the narcotic, too weak to kill him, plunges him into a sleep accompanied by the most horri-ble visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned and led to the scaffold and that he is witness-ing his own execution. The procession moves forward to the sounds of a march that is now somber and fierce, now brilliant and solemn, in which the muffled noise of heavy steps gives way without transition to the noisiest clamor. At the end of the march the first four measures of the idée fixe reappear, like a last thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow.

Part Five. Songe d’une nuit du sabbat (Night of the Witch-es’ Sabbath.) He sees himself at the sabbath, in the midst of a frightful troop of ghosts, sorcerers, monsters of every kind, come together for his funeral. Strange noises, groans, bursts of laughter, distant cries which other cries seem to answer. The beloved melody appears again, but it has lost its character of nobility and shyness; it is no more than a dance tune, mean, trivial, and grotesque: it is she, coming to join the sabbath. —A roar of joy at her arrival. —She takes part in the devilish orgy. —Funeral knell, burlesque parody of the Dies irae [a part of the requiem mass describing the end of the world], sabbath round-dance. The sabbath round and the Dies irae are combined.

A brief word about instrumentation is called for. Berlioz originally included two ophicleides in his score. This very French predecessor of the tuba was the bass voice of the brass in French orchestras from the mid-19th through the early 20th century. Some even made their way to military bands in the American Civil War. The name comes from the Greek words “ophis” (serpent) and “cleide” (keyed), clearly a bit of marketing to show that the new instrument is an improvement on the 17th century serpent. It is a keyed brass instrument, played with a mouthpiece like that of the bass trombone. The ophicleide’s inventor, Halary (AKA Jean Hilaire Asté) was granted a patent for the instrument in 1821, the first musical instrument to receive a patent.

Tickets 541-708-6400 ⎢ Rogue Valley Symphony ⎢ 33

The ophicleide was modeled after the Kent Bugles seen and heard parading through the streets of Paris in British military bands upon Welligton’s victory at Waterloo a few years before in 1815. After the acceptance of valves, the ophicleide fell out of favor and was replaced by the tuba. Like the modern baritone saxophone (which is a direct descendent of the ophicleide) they are difficult and expensive to make well. Tonight, the higher part will be played on an a 9-key ophicleide in C made in Paris around 1850. The lower part will be played on a modern tuba in F.

In 1831 Berlioz composed a sequel to the Symphony fantastique entitled Lélio, ou Le retour à la vie (Lélio, or the return to Life). This too was based on an unhappy love affair, this time with Marie Moke, who broke off her engagement to the composer in order to marry some-one else. The work alternates between spoken oratory and music for symphony and voices. This staid 19th century format may partially account for the piece’s obscurity today.

Appropriate for children aged 7 and up

May 18, 2019 at 2:00 pm Craterian Theater at the Collier Center

Instrument Petting Zoo precedes concert at 1 pm. Children have a hands-on discovery experience with the instruments of the orchestra

Free admission – no ticket needed

Discovery Concert

![Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 37 [Op. 37] - World Free Sheet Music (PDF… · Title: Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 37 [Op. 37] Author: Beethoven, Ludwig van - Publisher:](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/60d3b1eaecbf5b188a7ff4c5/piano-concerto-no-3-in-c-minor-op-37-op-37-world-free-sheet-music-pdf-title.jpg)