Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

-

Upload

afiqah-faizal -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

3.285 -

download

4

Transcript of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Lower GIT Bleeding & Management

Lower GI bleed

Lower GI Bleed Lower gastrointestinal bleeding is defined

as abnormal hemorrhage into the lumen of the bowel from a source distal to the ligament of Treitz.

Originates in the portion of GIT further down the digestive system –small intestine --colon --rectum --anus

more common in male > female.

This increase is largely attributable to the various colonic disorders commonly associated with aging (e.g., diverticulosis and angiodysplasia).

In more than 95% of patients with lower GI bleeding, the source of hemorrhage is the colon.

Categorization by pathology and intensity

By intensity – occult where the amount of blood is so small that it can only be detected by laboratory testing .

Acute mild Acute massive .

By pathology Benign Inflammatry Neoplastic

History

We should assess the chronicity of bleeding and medication use .

Particularly regarding anti coagulants such as warfarin.

low molecular weight heparin. inhibitors of platelet aggregation such as NSAID .

clopidrogel this can associated with mesentric

ischemia Use of digitalis should be documented because

this can associated with mesenteric ischemia.

Causes of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding:

Severe acute Moderate,chronic/subacute

Diverticular disease Anal disease(fissure,haemorrhoids)

angiodysplasia Inflammatory bowel disease

ischemia carcinoma

Meckel’s diverticulum Large polyps

angiodysplasia

Radiation enteritis

Solitary rectal ulcer

Other Causes of Severe Hematochezia1. Diverticulosis2. Colon cancer or polyps3. Colitis 4. Ischemic colitis5. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)6. Non-infectious colitis7. Infectious colitis8. Angioectasia9. Postpolypectomy bleeding10. Rectal ulcer11. Hemorrhoids12. Anorectal source (unspecified)13. Radiation colitis14. Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesions.15. Rectal varices.

symptoms bloody bowel movements, or black, tarry stools.

Symptoms associated with blood loss can include : Fatigue

Weakness Shortness of breath Abdominal pain Pale appearance Bright red or maroon stool can be from either a lower

GI source or from brisk bleeding from an upper GI source.

Long-term GI bleeding may go unnoticed or may cause fatigue, anemia, black stools, or a positive test for microscopic blood.

diagnosis Lower GI bleeding typically presents

with 1.hematochezia(which can range from bright-red blood to old clots.)

2.melena (If the bleeding is slower or from a more proximal source)

Hemorrhage less severe

more intermittent, commonly ceases spontaneously

The diagnostic modalities for lower GI bleeding are not as sensitive or specific in making an accurate diagnosis. .

After resuscitation has been initiated, the first step in the workup is to rule out anorectal bleeding is either by ;

Anoscopy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy. nuclear scintigraphy. Angiography. CT and computed tomography colonography. Colonoscopy. Barium enema. MRI Intraoperative endoscope

With significant bleeding, it is also important to eliminate an upper GI source.

An NG aspirate that contains bile and no blood effectively rules out upper tract bleeding in most patients.

colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is most appropriate in the setting of minimal to moderate bleeding; major hemorrhage interferes significantly with visualization, and the diagnostic yield is low.

in the unstable patient, sedation and manipulation may be associated with additional complications and can interfere with resuscitation.

Although the blood is cathartic, gentle preparation with polyethylene glycol, either orally or through an NG tube, can improve visualization.

Findings may include an actively bleeding site, clot adherent to a focus of mucosa or a diverticular orifice, or blood localized to a specific colonic segment, although this can be misleading because of retrograde peristalsis in the colon. Polyps, cancers, and inflammatory causes can frequently be seen

angiodysplasias are often very difficult to visualize, particularly in the unstable patient with mesenteric vascular constriction.

Diverticula are identified in most patients, whether they are the source of the hemorrhage or not.

Despite these limitations, recent studies report that colonoscopy is successful in identifying the bleeding source in up to 95% of patients

Diverticulosis, Diverticulitis

Colonic Polyps,malignancy

Hemorrhoids

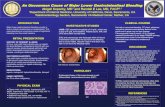

Radionuclide Scanning

These are helpful in identifying the sites of ongoing bleeding .

The scan are more sensitive than angiogram in detecting less rapid bleeding rate .1-.5 ml / min .

Radionuclide scanning with technetium-99m (99mTc)-labeled RBCs is the most sensitive .

It have a advantage of repeating the scan up to 24 hrs . After initial scan .

This is particularly helpful in in those pt whose have a slow bleeding in whom initial scan may not demonstrate any source of bleeding .

Initially, images are collected frequently and then at 4 hour intervals for up to 24 hours.

The tagged RBC scan can detect bleeding as slow as 0.1 mL/min and is reported to be more than 90% sensitive.

Active bleeding from Ascending Colon

Other diagnostics procedures CT angiogram mesenteric angiography -to identifying the vascular patterns of angiodysplasia, -localizing actively bleeding diverticula

Advantages and disadvantages of common diagnostic procedures used in the evaluation of lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Procedure Advantages Disadvantages

Colonoscopy • Therapeutic possibilities • Bowel preparation required

• Diagnostic for all sources of bleeding

• Can be difficult to orchestrate without on -call endoscopy facilities or staff

• Needed to confirm diagnosis in most patients regardless of initial

testing

• Invasive

• Efficient/cost - effective

Angiography • No bowel preparation needed • Requires active bleeding at the time of the exam

• Therapeutic possibilities • Less sensitive to venous bleeding

• May be superior for patients with severe bleeding

• Diagnosis must be confirmed with endoscopy/surgery

• Serious complications are possible

Radionuclide scintigraphy

• Noninvasive • Variable accuracy (false positives)

• Sensitive to low rates of bleeding • Not therapeutic

• No bowel preparation • May delay therapeutic intervention

• Easily repeated if bleeding recurs • Diagnosis must be confirmed with endoscopy/surgery

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

• Diagnostic and therapeutic • Visualizes only the left colon

• Minimal bowel preparation • Colonoscopy or other test usually necessary to rule out right - sided lesions

• Easy to perform

Video Capsule Endoscopy

Capsule endoscopy uses a small capsule with a video camera that is swallowed and acquires video images as it passes through the GI tract.

This modality permits visualization of the entire GI tract, but offers no interventional capability.

It is also very time consuming because someone has to watch the video to identify the bleeding source, and then a means to deal with the pathology has to be developed.

Intraoperative Endoscopy

Intraoperative enteroscopy is reserved for patients who have transfusion-dependent obscure-overt bleeding in whom an exhaustive search has failed to identify a bleeding source.

This typically uses a pediatric colonoscope introduced through the mouth or through an enterotomy in the small bowel made by the surgeon.

Causes and Management

1- Diverticular Disease the most common cause of significant lower GI bleeding. common in Western countries with frequency of 50% in

older adults. By contrast, diverticula are found in fewer than 1% of continental African and Asian populations.

colonic diverticula are herniations of colonic mucosa and submucosa through the muscular layers of the colon.

Bleeding generally occurs at the neck of the diverticulum .

believed to be secondary to bleeding from the vasa recti(small arteries) as they penetrate through the submucosa.

Of those that bleed, more than 75% stop spontaneously, although about 10% rebleed within 1 year and almost 50% within 10 years

Diverticular hemorrhage should be classified carefully based on findings at colonoscopy, angiography, anoscopy, terminal ileum examination, push enteroscopy (when colonoscopy reveals diverticulosis without stigmata and no other significant lesions seen in colon and by anoscopy)

Management: blood transfusion of fewer than four units of packed

RBCs. Endoscopic Hemostasis - colonoscopic hemostasis of

actively bleeding diverticula has been reported using MPEC cauterization, epinephrine injection(a sclerotherapy needle can be used to inject epinephrine diluted 1:20,000 in saline), hemoclips, fibrin glue, or combinations of epinephrine and MPEC or hemoclips.

Electrocautery can also be used, and most recently, endoscopic clips have been successfully applied to

control the hemorrhage.

Hemostatic clip application in bleeding diverticulosis

If none of these maneuvers is successful or if hemorrhage recurs—> Angiography and surgery – angiography embolization can be performed in selected cases of diverticular bleeding, but with a risk of bowel infarction, contrast reactions, and acute kidney injury.

Surgical resection for diverticular bleeding is rarely needed and is reserved for recurrent bleeding. The decision to operate is best guided by colonoscopic, angiographic, or nuclear medicine studies.

Blind subtotal colectomy, often performed in the past when a definite bleeding site could not be identified, should be avoided as possible.

2- Angiodysplasia/Vascular Ectasias Hemorrhage secondary to angiodysplasia

accounts for up to 40% of lower GI bleeding.

Angiodysplasias of the intestine, also referred to as arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), are distinct from hemangiomas and true congenital AVMs..

They are thought to be acquired degenerative lesions secondary to progressive dilation of normal blood vessels within the submucosa of the intestine.

The hemorrhage tends to arise from the right side of the colon, -the most common location=cecum- it can occur anywhere in the colorectum and small bowel.

Most patients present with- chronic bleeding; in up to 15% of patients -hemorrhage may be massive. -Bleeding stops spontaneously in most cases

diagnosed by = colonoscopy =visceral angiography. =laparotomy with on table colonoscopy

treatment of choice : endoscopic thermal ablationIf these measures fail or bleeding recurs and the lesion has been localized, segmental resectionmost commonly right colectomy, is effective.

3- Colorectal cancer Colorectal cancer

3rd commonest malignancy in UK

M:F = 3:1 peak age 45-70yo

Risk Factor’s: FH of Colorectal Ca, FAP, HNPCC, Prev Hx of Colon,Breast, Ovarian or Uterine Ca Prev Hx of Adenomatous Polyps Chronic UC or Colonic Crohn’s disease Western diet, Obesity, Smoking

Presentation depends on site: Left-sided:Altered bowel habit (constipation & diarrhoea), PR bleeding bright

red coating the stool, Tenesmus, Painful defecation? Small diameter of Left Colon Tendency towards obstruction

Right-sided: Present later. Weight loss, Right abdo pain/mass, Tendency to bleed, Blood mixed in with stools, high incidence of IDA

Emergency (40%): Obstruction, Perforation w/Peritonitis, Acute Haemorrhage

Investigations: FBC Microcytic hypochromic anaemia, LFTs deranged with hepatic spread + Faecal occult blood Sigmoidoscopy/Colonoscopy + biopsy Lesion (w/ 3-5% synchronous) Barium Enema may show ‘Apple core’ appearance CT/MRI for rectal cancers, local pelvic spread and metastasis Liver US Hepatic Mets Raised Carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) used for monitoring

Treatment: Surgical Resection with curative intent +/- Chemo Right Hemicolectomy Caecal, Ascending, Proximal

Transverse Ca Left Hemicolectomy Distal Transverse, Descending Sigmoidectomy Sigmoid Ca Anterior Resection Low sigmoid/High Rectal Ca Abdominoperineal (A-P) Resection Low Rectal

Tumours <8cm from Anal canal permanent colostomy **Hartmann’s Carcinoma w/ Acute Obstruction

(excision, colostomy, rectal stump) Other options: Chemotherapy (5-FU) for Duke’s

B&C, RT, Palliation

4- Anorectal Disease

The major causes of anorectal bleeding : 1.hemorrhoids, 2.anal fissures, 3. colorectal neoplasia. hemorrhoids: the most common : only 5% to 10% bleeding.Anorectal hemorrhage is not massive and presents as bright-red blood per rectum

Hemorrhoidal bleeding

Anal fissure

1. Bright red 2.Occur : during/after defecation

1.Bright red bleeding 2.occur: during defecation + anal pain

3.Diagnose by : protoscopy4.colonoscopy/barium enema -to exclude coexisting colorectal cancer

3.May reqiure surgery (due to forceful straining during passage of hard stool may cause tears)

5. age:over 40 years 4.Medically ttt: stool bulking agents : water intake : stool softners : topical nitroglycerin ointment/ diltiazem

5- Colitis

Inflammation of the colon is caused by a multitude of disease processes.

inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis)

Infectious colitis . Ischemic colitis ; present as painless hematochezia (results from mucosal

hypoxia and is thought to be caused by hypoperfusion of the intramural vessels of the intestinal wall) or painful hematochezia (caused by large vessel occlusion and has worse outcomes) with mild left-sided abdominal discomfort.

Radiation proctitis after treatment for pelvic malignancies,

and ischemia.

Ulcerative colitis 1. much more likely than Crohn's disease to present with GI bleeding.

2. A mucosal disease 3.starts distally in the rectum4. progresses proximally 5.occasionally involve the entire colon.

Patients can present with up to 20 bloody bowel movements per day.

These episodes are accompanied by

abdominal cramping, tenesmus, and occasionally abdominal pain

Ulcerative colitis6.The diagnosis -careful history -flexible lower endoscope with biopsy.

7. Medical therapy: steroids, :5-aminosalicylic acid :(ASA) compounds, :Immunomodulatory agents, :supportive care

8.Surgical therapy -is rarely indicated (unless the patient develops a toxic megacolon or hemorrhage that is refractory to medical management.)

6- Mesenteric Ischemia

Mesenteric ischemia can be secondary to either acute or chronic arterial or venous insufficiency.

Predisposing factors -preexisting cardiovascular disease - recent abdominal vascular surgery -hypercoagulable states, - medications (vasopressors and digoxin), -vasculitis

Patients present with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea.

CT scanning often shows a thickened bowel wall.

The diagnosis: flexible endoscopy which reveals edema, hemorrhage, and a demarcation between the normal and abnormal mucosa.

Treatment :focuses on supportive care :bowel rest, :intravenous antibiotics, :cardiovascular support, and : correction of the low-flow state.

In 85% of cases, the ischemia is self-limited and resolves without incident, although some patients develop a colonic stricture.

15% of cases surgery is indicated because of- progressive ischemia -gangrene.

During the surgery -resection of the ischemic intestine and -creation of an end ostomy is indicated.

7- Meckel's diverticulum

Bleeding of the diverticulum is most common in young children, especially in males who are less than 2 years of age

Symptoms : bright red blood in stools (hematochezia), weakness,

abdominal tenderness or pain, and even anaemia in some cases

Diagnosis : - A technetium-99m (99mTc) pertechnetate

scan, also called Meckel scan investigation of choice in children. Colonoscopy and screenings for bleeding disorder. Angiography can assist in determining the location and severity of bleeding

- Capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy(via an oral or rectal approach).

Treatment: Treatment is surgical, which is small bowel

resection (with bowel complication) and simple resection (without complication).

8- Postpolypectomy bleeding Bleeding recurs after approximately 1% of

colonoscopic polypectomies. The bleeding occurs most commonly five to seven days after polypectomy but can occur from 1 to 14 days after procedure;

it generally self-limited and mild to moderate, with 50% to 75% of patients requiring blood transfusions.

Endoscopic management techniques: - for delayed postpolypectomy ulcer bleeding on the

stigma are found and similar to those used for peptic ulcer hemorrhage,

- including : epinephrine injection, thermal coagulation, hemoclip placement, and combination therapy.

Postpolypectomy bleeding

9- Dieulafoy’s lesion of the small intestine and rectum Uncommon causes of major gastrointestinal lesion

It consists of a large caliber artery that protrudes through a mucosal defect in the stomach causing significant and often recurrent hemorrhaging from a pinpoint non-ulcerated arterial lesion.

Rectal Dieulafoy’s lesions are large submucosal arteries with overlying mucosal ulceration that cause massive bleeding. And it can be treated by endoscopic hemostasis.

history of NSAID intake, peptic ulcer symptoms, or alcohol abuse is usually absent, the condition is difficult to recognize.

Dieulafoy lesion should be considered when evaluating any acute and recurrent major gastrointestinal bleeding.

If unrecognized, it may cause a life-threatening hemorrhage. Usually, the mean hemoglobin level on admission has been reported to be between 8.4-9.2 g/dL in various studies.

Diagnosis:Awareness of the condition is a key to accurate diagnosis. It can be easily overlooked at endoscopy as concomitant

lesions such as ulcers or varices may wrongly be considered responsible for the bleeding episode.

Treatment: -by endoscopic modalities like electrocoagulation and

successfully achieves permanent hemostasis in 85% of cases.

This case illustrates a rare and inherently difficult lesion to recognize, because it presents with very low hemoglobin, which is usually uncommon in Dieulafoy lesion, and did not have any risk factor for gastrointestinal bleeding.

In practice, we have to consider unusual causes of common diseases to decrease their mortality and morbidity.

-argon plasma coagulation.-Bipolar coagulation.-hemoclip placement.-proton pump inhibitor therapy.

Actively bleeding jejunal Dieulafoy lesion found during double-balloon enteroscopy. Red blood pooled within a short segment of jejunum (A). The area after water lavage, revealing a focal area of active bleeding and a very small protruding vascular structure (the Dieulafoy vessel) (B). Another example of focal active bleeding from a Dieulafoy lesion, seen near the bottom of the endoscopic image (C).

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced jejunal ulcer (A) with a small visible vessel (on left side of ulcer, at approximately 8 o'clock position). The visible vessel began bleeding spontaneously during double-balloon enteroscopy (B). Hemostasis was achieved with epinephrine injection and hemoclips placement (C).

10- Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome It is a rare syndrome characterized by venous

malformations in the skin, soft tissue, and GI tract. Bleeding usually occurs in childhood and

continues into adulthood and results in chronic iron deficiency requiring iron replacement and transfusions.

Diagnosis: On endoscopy , lesions appear as large protuberant polypoid venous bleb; they can occur anywhere in the GIT, but especially in the small bowel and colon,

Treatment: Endoscopic band ligation or surgical resection.

Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome

Intra-operative enteroscopy. Blue rubber bleb nevus of the distal jejunum

Vascular malformation typically seen in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome.

Characteristic endoscopic appearances of small intestinal venous malformation in a patient with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (A, B).

Thank You

1.Amer Ridzuan bin Katiman(25)2.Afiqah binti Muhamed Faizal(26)3.Ainatul Mardhiah binti Che Wan Ahmad (27)

![Acute Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage: Radiologic Diagnosis ... · bleeding are peptic ulcer disease, variceal bleeding, Mallory-Weisstear,vascularlesions,andneoplasms(Table1) [2]. Lower](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/6021c6749b53ea1a471bc940/acute-gastrointestinal-hemorrhage-radiologic-diagnosis-bleeding-are-peptic.jpg)