Kogod Now - Spring 2012

-

Upload

american-university-kogod-school-of-business -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Kogod Now - Spring 2012

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY KOGOD SCHOOL OF BUSINESS | SPRING 2012

BONDS OF PARTNERSHIP Do We Prepare Partners Adequately For Challenges?

CRASH LANDING Congress’ Attempts to Deflate Golden Parachutes

WOMEN’S WORTH Why a Token Female Board Member Cannot Add Value

FROM THE DEAN

LETTER BY MICHAEL J. GINZBERGDEAN, KOGOD SCHOOL OF BUSINESS

Nowhere is this more true than in the case of family firms. By exploring this nuance, Professor Ronald Anderson zeroes in on the unique forces at play in family firms that impact corporate gover-nance decisions. His groundbreaking research has opened up entirely new avenues of thought on what family ties do to, and for, businesses. His collabora-tions with Associate Professors Parthiban David and Augustine Duru have revealed that the closely held firms with the most market value are also the most transparent; he has also uncovered that Great-Aunt Tilly just might be trading a little too early on that undisclosed quarterly earnings report.

Barry Dewberry, MS ’82, provides a captivating first-person perspective on the tough choices family members who double as managers must make when planning for the future of the firm.

CEO compensation decisions create an intriguing quandary for the boards of family and publicly held firms alike. Assistant Professor Yijiang Zhao joins his colleagues David and Duru to consider why a handsomely rewarded chief executive, hired to steer a company into new seas of opportunity, may be taking major risks that yield little return.

Ready to raid the external audit team for finan-cially savvy leadership? Take heed, warns Assistant Professor Yinqi Zhang: negative investor percep-tion, along with regulation—including the Sarbanes-Oxley Act—encourages greater distance between former auditors, auditing firms’ extraneous business services, and their clients.

Across the board, our faculty are pushing past the accepted thinking in finance, accounting, taxa-tion, management, and more. Through their collabo-rations with private- and public-sector businesses, government agencies, and a bevy of nonprofit orga-nizations, new knowledge is being created to shape the markets of today and tomorrow.

Creating sustainable value for shareholders, now and in the future, is a complicated endeavor and a key concern of Kogod School of Business faculty. The carnage wrought by short-term thinking peppers daily headlines and fills congressional committee dockets. Market perceptions formed around “green-ing” core business functions, like supply chain management, are being reconsidered by Professor Bruce Hartman and Assistant Professor Ayman Omar. And DuPont’s chief sustainability officer, Linda Fisher, weighs in on how the global science giant helps its clients consider sustainability as a business priority.

Vilifying corporations, and their leaders who “make too much” and “think too little,” has become a national pastime—one that will certainly remain an undercurrent in the unfolding presidential race.

Yet the long-term value that business gener-ates cannot be distilled into a single number. For our part, we’ll keep digging deeper into the multi-faceted concept of value creation, and examine how a little perspective may help bridge the seem-ingly insurmountable divide between K Street and Main Street.

Few would argue that good corporate governance is not important to the long-term success of businesses and our entire financial system. There is, however, much less agreement on exactly what constitutes good governance.

IN THIS ISSUE1 FROM THE DEAN

2 THE RISK-RETURN PARADOX

4 O PARTNER, WHERE ART THOU?

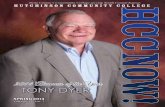

COVER STORY 8 Blood in Business 13 Relative Leaders

KOGOD TAX CENTER 18 Golden Parachutes Get a Lift From Congress

22 RUSSIA’S CORRUPT FREE MARKET

24 DUX FEMINA FACTI Women and Board Leadership

32 KOGOD STANDOUT Adventures in Silicon Valley

34 THE FRAGILE NATURE OF SUPPLY CHAINS

39 SUSTAINABILITY’S SPLINTER EFFECTS

40 FINDING FEDERAL SAVINGS IN THE STRATOSPHERE

PRACTITIONER PERSPECTIVE 42 When Succession Planning Goes Beyond the Family Barry Dewberry, Chairman, Dewberry, Inc. 44 The Business Case for Sustainability Linda Fisher, Chief Sustainability Officer, DuPont

47 REGULATING INDEPENDENCE

48 WEB EXCLUSIVES Beyond the Page

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

1

market discipline. In almost every case, the market measures tempered the paradox.

In the presence of weak market mechanisms, the risk-return relationship was negative, as the paradox predicts. However, as the market mecha-nisms gained influence, the relationship between risk and return became less negative. This relation-ship even became positive as the market mecha-nisms, such as monitoring by dedicated institutional owners, grew stronger.

“The returns to risk taking are increasingly positive as the firm faces stronger market forces,” Zhao said.

This was what they had hoped. And in the context of manager incentives, it’s clear what led to these results.

A vigilant board of directors, for example, offers a powerful defense against brash business plans. Board members hold many trump cards; they sign off on executives’ compensation plans, and they also approve—or disapprove—proposals. The presence of more outsiders on a board, frequent board meet-ings, and the separation of duties on the board have all proved to take the edge off excessive risk taking.

IT STOPS AT THE TOPThere was one notable exception to the market’s influence, in the realm of CEO compensation.

As a corporate governance measure, compensa-tion should help to ensure that managers take risks only when they are sure to be followed by a return. When motivated correctly, executives should swing for the fences with shareholders’ returns in mind, rather than their own payoffs. But the researchers point out that this does not hold true when the compensation structure isn’t working.

Certainly, CEO compensation has been heavily scrutinized and hotly debated. But the risk-return paradox has never before been considered in terms of the influence of market mechanisms, compensa-tion being one.

CEOs are compensated in a myriad of ways, but often the majority percentage of their salary is dependent on performance. A typical compensation package includes a mix of total cash compensation (salary, bonuses), long-term incentives (restricted stock, stock options), benefits, and perks.

Two compensation methods that the professors focused on were CEO ownership and stock options. They found that these two components behaved quite differently when analyzed.

Fundamentally, an ownership stake exposes CEOs to both the upside and downside of a risk.

Their regression showed that CEO ownership, like the other market mechanisms they studied, helped alleviate the risk-return paradox.

Not so with CEO stock options. That’s not too surprising; if stock options are never exercised, the CEO is not any worse for the wear (even though the shareholders suffer).

Let’s say that CEO Barney Johnson is given the rights to buy 10,000 shares of Cheap ’N’ Quick Restaurant Chain for $100 a share in January 2013. If the company’s stock is trading at $120 a share at that point in time, Barney’s made a cool $200,000—without investing a personal cent. And if the company’s stock is only trading at $75 a share at the time, well, he simply won’t exercise his options. At that point the options are called “out of the money.”

“The stock options shield the manager from the downside, so there is a tendency to take excessive risks; that is what we are seeing,” Duru said. “All we’re trying to point out is that stock options could lead to distorted incentives.”

NO MAGIC SOLUTIONThe professors’ research clearly indicates that strong market mechanisms provide some relief for the risk-return relationship. But the larger ques-tion remains to be answered: Can the market truly mitigate managers’ actions as they seek to climb mythical beanstalks? Without the ability to isolate the market’s individual influences, the remedy to the problem could remain as elusive as Jack himself.

David, Duru, and Zhao expect to submit their paper to journals this year.

THE RISK-RETURN PARADOX

Ever since young Jack traded his cow for some magic beans, society has bought into the concept that greater risk promises greater reward. The relationship is taken for granted as fact; empirically, researchers have shown it is fiction.

There is a negative relationship: firms that take bigger risks get lower returns. “This flies in the face of what we would expect to find,” said Associate Professor Parthiban David, who holds the Collins Chair in Strategic Management. His expertise is in corporate governance.

The risk-return contradiction, known as Bowman’s paradox, has befuddled management scholars for years. It’s unavoidable that firms must undertake risk—each time they enter a new market, launch a new product, or look for creative ways to cut costs. But they should do so only when rational decision making is at work.

Here’s the conflict: managers, not shareholders, are the ones making the decisions. And their biases and behaviors can cause excessive risk taking in two common ways, agree like-minded researchers.

In Framing, managers categorize performance as either a gain or a loss. When they see a clear point for the “Win” column, risk taking seems like a threat. But when a project is seen as a loss, then risks are suddenly viewed in a new light: as potential salvation. Simply classifying a project as a loss prompts the manager to take an excessive risk to get it back on track.

Overconfidence is easier to relate to. By overes-timating their own competence or the firm’s future prospects (or by underestimating their competition), prideful managers are led astray. They buoy their own belief in the likelihood of a positive return.

Aligning risk and return is a riddle worth solving, because there are deep consequences for the company when a risk doesn’t pay off. Beyond the direct financial hit to the firm, risks can lead a firm to grow its personnel or reallocate its resources gratuitously. They can also negatively affect consumers’ confidence in the firms’ products.

No one is arguing that risks should never be taken. On the contrary, “managers must be induced to take risks,” the authors write, “but only those that are likely to produce gains.”

CHECKS AND BALANCESFor the first time, the Kogod professors looked at the perplexing risk-return relationship in the context of market mechanisms. They wanted to unearth whether the market’s role could help explain the paradox.

Is the market, left to its own devices, capable of correcting managers’ mistakes? “Market mechanisms might be the reason that the risk-return relationship is not working well,” said Associate Professor Augustine Duru, who had previously studied CEO compensation in the context of accounting.

In theory, these mechanisms should constrain the managers from taking excessive risks. For example, the labor market could act as a constraint to an overzealous CEO; if he takes unwise risks and is fired, he may not be able to find another job.

David, Duru, and their colleague, Assistant Professor Yijiang Zhao, undertook the project. Zhao’s research background in corporate gover-nance (in particular, takeover markets) and financial reporting primed him for the effort.

The researchers studied how two broad types of mechanisms—corporate governance measures and product market competition—would affect the risk-return relationship. With a sample of more than 2,100 firms from the S&P 1500, the authors studied performance over a 12-year period and tested the interaction between the relationship and each of these market mechanisms:

• Institutional ownership

• Blockholder ownership (concentrated owners)

• External corporate governance (measured through firms’ antitakeover provisions)

• Board of directors’ monitoring

• CEO ownership

• CEO stock options

• Product market competition

Using regression analysis, the professors simu-lated the effect of each mechanism on the risk-return relationship. They controlled for other factors that might affect performance, such as firm size, leverage, and diversification, as well as the possi-bility that risk taking can arise from within—say, in firms operating in high-performance industries (like the high-tech sector).

They found that Bowman’s paradox is direr for companies that are not subject to efficient

ARTICLE BY JACKIE SAUTER

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

3

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

2

O PARTNER, WHERE ART THOU?

Contrary to the romantic notion of a passionate dreamer going it alone, most start-ups are founded by partners, not solo entrepreneurs. Think of some of the high-tech companies that have risen to fame and stunning capitalization in almost no time: Google, Facebook, LivingSocial. All started by partners.

DAVID GAGE, PHD, IS A CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST AND MEDIATOR, CO-FOUNDER OF BMC ASSOCIATES, AND ADJUNCT PROFESSOR AT THE KOGOD SCHOOL OF BUSINESS. HIS BOOK ON EFFECTIVE PARTNERSHIPS, THE PARTNERSHIP CHARTER: HOW TO START OUT RIGHT WITH YOUR NEW BUSINESS PARTNERSHIP (OR FIX THE ONE YOU’RE IN), WAS PUBLISHED IN 2004.

The trend isn’t limited to cutting-edge tech firms. Partners also founded some of the best-known companies of the 20th century: Black & Decker, Warner Bros., Hewlett-Packard. And then there are 3M, Costco, Microsoft, Intel, and Apple. Partners, too, founded them.

PARTNER ADVANTAGESPartners—whether they are family members or not—are extremely important because their pres-ence boosts the chance of success. It seems like common sense; after all, there is strength in numbers. Generally speaking, partners mean greater resources: more skills, energy, capital, psychological support, networking capabilities.

Need further proof? A study published last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research tried to determine whether having partners is really an advantageous strategy for entrepreneurs trying to commercialize inventions. The results were impres-sive. Projects run by partners were five times more likely to reach commercialization, and their average revenues were approximately 10 times greater than projects run by solo entrepreneurs.

Research from Marquette University backs that up. The researchers investigated a sample of nearly 2,000 companies, categorizing the top performers as “hypergrowth” companies. Solo entrepreneurs founded only 6 percent of the hypergrowth compa-nies. Partners founded an amazing 94 percent.

One for all and all for one! Even Alexandre Dumas knew there needed to be three Muske-teers—not one.

UNDENIABLE RISKSSo why wouldn’t all start-ups begin with co-owners at the helm? Because there is also a dark side to the partner story.

There are no hard numbers that spell out how many companies die premature deaths as a result

of partner difficulties. Private companies are not obliged to undergo a postmortem, but estimates often run to more than 50 percent failure within a few years.

We know that many business advisers regu-larly warn entrepreneurs not to start businesses with partners, offering horror stories from past clients. “There are too many risks involved, and it’s extremely difficult to extract yourself from part-ners,” they warn.

The risks are numerous. Many would-be business owners are under the dangerous misconception that completing certain legal documents fully prepares them for partnership. If anything, these legalities give partners a false sense of security that they have done all they need to do to protect themselves.

If we accept that partner problems are a leading cause of start-up failure, we have to ask: Why aren’t we doing more to educate and train entrepreneurs to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks of co-ownership? Why aren’t organizations that fund entrepreneurial research helping start-ups prepare better for the challenges of having partners? Why aren’t VCs asking start-ups to do more to ensure their survival?

As advisers to entrepreneurs and business students, we are not guiding them out of harm’s way. We are not teaching them sufficiently about either the risks of having partners—turf battles, person-ality clashes, values conflicts, money disputes, distrust—or how to minimize them.

The box office hit “The Social Network” helped bring this issue to light in 2010, when moviegoers turned out en masse to watch the story of Mark Zuckerberg and his ill-fated Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin unfold on the big screen. A high-profile multimillion-dollar lawsuit between the two was eventually settled out of court.

And Saverin wasn’t the only one to haul the Facebook co-founder to court. How do we prepare

entrepreneurs for the Winklevoss twins of the world—those who publicly allege they hold partner status, even though they may not?

But helping future Mark Zuckerbergs mitigate their risks is not sufficient either. We need to also teach them how to proactively create healthy partnerships.

PREPARATION FOR SUCCESSReviewing the curricula of our peer business schools reveals that very few offer courses for entrepre-neurs who want to learn how to set up healthy business-partner relationships. Courses on lead-ership, managing teams, choosing among legal entities, and identifying funding are valuable to entrepreneurs, but miss the mark when it comes to having partners.

Developing and maintaining good relationships with partners is not the same as leading an execu-tive team or managing a company of a thousand employees. The intimate dynamics among part-ners are quite different from the dynamics of any employer-employee relationship.

True co-owners tie their futures and fortunes together in a unique way. Partners have a fiduciary duty, and a loyalty, to one another that employers do not have to their employees, even if they give them honorific “partner” or “associate” titles.

Business schools aren’t the only ones behind the partner curve. Incubation labs, economic devel-opment centers, the Small Business Association, venture funds, and even other private organizations focused on helping entrepreneurs seem to miss the importance—and the challenges—of having partners.

To address some of these deficiencies, I devel-oped and have taught a graduate course at Kogod for the past 10 years on managing private and family businesses. It covers the range of partner issues described above, delves into the value of co-ownership, and gives students concrete strate-gies to minimize the risks. In my view, more schools need to experiment with courses to help students understand partnerships.

ABSENCE OF ATTENTIONIf we are going to improve our performance in teaching about partnership, it will be important to create a sound base of research for the lessons we convey. To date, there is very little scholarship available on this subject.

One reason for this is the complexity of the field. How many times have you heard the famous line, “It’s not personal, it’s just business” from “The Godfa-ther”? For partners, family business owners, and even mafiosi, it couldn’t be further from the truth. Almost everything that occurs among partners in closely held companies is both personal and business. Co-owners constantly describe their partner relationship as a marriage, but hasten to add, “Except I spend more time with my business partner!”

Recognizing the duality is advantageous. Researchers need to develop a realistic conceptu-alization of the challenges that partners face, one that fully appreciates the interpersonal-business pairing of partnerships.

Anything less will be too simplistic to be helpful. The focus has to be on the individuals who do busi-ness together, not on the business itself.

Unfortunately, researchers who want to study partners often feel slightly out of their element. They are typically experts in one discipline—psychology or business—but not both. Researchers from different disciplines may need to collaborate—as partners!—to study this topic effectively.

Another hurdle is the fact that closely held businesses are truly closely held. They are private, which is an advantage for co-owners but a barrier for researchers. Researchers will need to provide partners with an incentive to share private infor-mation. Without a reason to open up, partners will likely remain something of a mystery.

MEDIATION AS AN ACADEMIC RESOURCE As the founder of a firm that specializes in preventing and resolving co-owner disputes, I have learned that mediation is not only a process that partners usually agree on when they have serious differences. It is also a process that opens the door to the private, inner workings of partners.

I discovered that the confidentiality of media-tion helps partners open up and discuss things

THE INTIMATE DYNAMICS AMONG PARTNERS ARE QUITE DIFFERENT FROM THE DYNAMICS OF ANY EMPLOYER-EMPLOYEE RELATIONSHIP.

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

5

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

4

they would otherwise never reveal to a stranger, from plans to sell the company to “creative” and sometimes ill-conceived methods for taking money from the business.

Behind this shield of confidentiality, partners in mediation quickly realize that they only hurt them-selves if they play their cards too close to the chest. Mediators, like myself, strive to convince the parties that to be effective, we must know everything that has transpired. We need to understand how their partnership works.

Part of the conflict resolution process involves separate, individual caucus sessions in which each partner has a chance to lay his or her story completely on the table. They are often quick to seize this opportunity, because they believe that if they don’t disclose something, another partner almost certainly will—and no one wants to be seen as withholding key information, or appear to have something to hide. Partner mediations have thus been fertile ground for learning about what makes partners tick—and stop ticking.

CASE IN POINTHere’s one example, from more than two decades of mediating business partnerships, that illustrates one of the common challenges partners face and for which they are ill prepared: determining owner-ship percentages.

These partners, who ran a company in an emerging medical device industry, were not neophytes by any stretch of the imagination. Numbering five in total, they included a successful CEO from a regional consulting firm, an attorney, a seasoned marketer, a physician-investor, and an established medical researcher.

As all partners must do, they had to determine their respective percentages of ownership. From the starting gate, each began jockeying for as large an interest as possible. Like forty-niners staking their gold rush claims, each of the five fought for

his share of equity. Eventually they followed the conventional advice of their advisers and “filled in the blanks” of an operating agreement. The storm appeared to pass.

Exactly one year later, the consulting firm CEO (now the CEO of the new company) and the researcher claimed that they had all agreed to review everyone’s performance after a year’s operation, and then adjust their percentages accordingly. The lawyer and the marketing director disagreed vehemently, claiming that the idea of revising the percentages had been raised but then dismissed. The physician-investor, a friend of both the marketing director and the CEO, demurred, saying he was unable to remember the decision.

The resulting deadlock took a toll on their rela-tionships, their motivation, and their productivity. Worse, their employees were becoming aware of the disagreement. With threats of lawsuits hanging in the air, the partners agreed to try mediation.

The convoluted dynamics among the partners quickly became apparent in individual discussions with mediators. The mediation was an in-depth study of the complexity of determining ownership percentages, and it revealed how tightly the part-ners’ egos were wrapped around these percentages. Since they were united around the goal of growing and selling the company in a few years, they were acutely aware of the value of every percentage point.

With the help of the mediators, the owners even-tually resolved the equity battle. In brief, some of the partners agreed to reduce their percentages to free up equity for certain key employees, and they shifted certain management responsibilities to resolve underperformance issues. The details can be found in my book on having partners, The Partnership Charter: How to Start Out Right With Your New Business Partnership (or Fix the One You’re In).

Four things are important about this case study. First, mediation provided an opening to better understand how partners operate. Second, the plot line is very common: some variation of this true story occurs in most partnerships.

Third, despite it being a common problem, there is almost nothing written to help entrepre-neurs with a more rational process for determining equity percentages. And finally, this story describes but one of the many challenges partners may face.

THE BOOK—AND BEYONDThe lessons I learned from scores of mediation clients became the blueprint for The Partnership Charter. The book talks on the interpersonal side about personalities, values, expectations, and fair-ness. On the business side are roles and responsi-bilities, decision making, governance, money, and ownership. Partners also have to decide how they will handle differences.

A scenario-planning process forces partners to prepare for the uncharted waters that lie in front of them. Some of the what-ifs they need to prepare for are unique to having partners:

• What happens if a partner hires a key employee whom the other partner(s) dislike(s)?

• How will you decide how to respond to an unsolicited buyout offer from a competitor?

• What if the partners decide to close the busi-ness and the company has nothing but debt?

Though mediation has taught us a great deal, we need to investigate the inner world of partners with more typical research paradigms and tech-niques. The research topics are many, but could include the importance of financial transparency, whether establishing a governing board mitigates conflict, and whether a partnership with a best friend improves, or lessens, the chance of success.

Despite the gap in partnership know-how, we have learned a significant amount about what causes partners to “fall out” with one another. While there are numerous topics partners must address, the most important step they can take is to engage in a comprehensive planning process.

To get the ball rolling, my business partner and I have also set up a website for The Busi-ness Partner Institute, an organization that can help people to share research ideas and explore interdisciplinary collaboration.

By joining efforts—as partners do—I have no doubt that we can dramatically improve the short- and long-term success rate of start-ups.

PARTNER MEDIATIONS HAVE BEEN FERTILE GROUND FOR LEARNING ABOUT WHAT MAKES PARTNERS TICK AND STOP TICKING.

WHAT IF?

WHAT IF THE PARTNERS DECIDE TO CLOSE THE BUSINESS AND THE COMPANY HAS NOTHING BUT DEBT?

HOW WILL YOU DECIDE HOW TO RESPOND TO AN UNSOLICITED BUYOUT OFFER FROM A COMPETITOR?

WHAT HAPPENS IF A PARTNER HIRES A KEY EMPLOYEE WHOM THE OTHER PARTNER(S) DISLIKE(S)?

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

7

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

6

Sorry! WE ARE

CLOSED

$

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

9

ARTICLE BY JACKIE SAUTER

If "The Godfather" truly provided the answer to any business question, there would be a lot less angst about how to motivate employees. It’s not a stretch to contend

that business was simpler under the Mob’s thumb. Processes and procedures were understood: family came first. The appearance of propriety was

paramount. No Sicilian could refuse a request on his daughter’s wedding day. And if gambling debts aren’t paying the bills,

it’s time to diversify the business. Why not try an emerging market?

JOHN DOE JR.

JOHN DOE III

RACHEL ROEJACOB DOE SR.

RICHARD ROE SR.

JOHN DOE IV

REGINA ROEJACOB DOE JR.JACKIE DOE RICHARD ROE JR.

JANE DOE

JOHN DOE SR.

But imagine how turbulent the markets would be if a violation of respect resulted in literal bloodshed. It would make 2008 look like a banner year.

The key was that in the gangster-ridden world of Old New York, everyone in the “organization” had aligned goals: preserve pride, profit, and a pulse.

The same can’t be said for modern-day firms. This indisputable fact has given rise to the field of corporate governance, which endeavors to mitigate the myriad conflicts between managers and shareholders.

It all boils down to a matter of diverging interests. Shareholders’ first priority is to maximize their

own wealth: stock prices should go up, dividends should be paid.

“Shareholders are often thousands of miles away; they generally don’t want to know about the day-to-day operations…there is a separa-tion between management and ownership,” said Professor Ronald Anderson, who has spent the last decade researching corporate governance, particu-larly in family firms. Anderson holds the Gary D. Cohn Professorship in Finance.

On the other hand, no one is entirely sure what company managers hold sacred. “They should be focused on maximizing shareholder wealth, but they have a natural tendency to protect themselves and maximize their own utility,” Anderson said, citing examples like the implosion of Enron and scandal at Tyco. “It’s a problem that has reared its head a lot over the last 10 to 12 years.”

IT’S NOT PERSONALA company’s ownership structure should be a super-fluous ingredient in its success, but Anderson and his colleagues have proved that family owners are of a unique flavor. Firms with controlling family owners (those who wield sufficient power to enforce deci-sions) are singularly motivated. Though the family members may not be as hands-on as Vito Corleone, their firms make distinctive investment choices, and flourish—or flounder—in certain circumstances.

Spurred by the lack of research on family firms, Anderson and colleague David M. Reeb, now at the National University of Singapore, began in the late

1990s to evaluate family ownership and its connec-tion to firm performance. Their findings changed the way academics and practitioners view this previously underrated demographic.

Further research at Kogod has investigated family firms’ transparency, proclivity for insider trading, investment choices, and the impact of “family-style” debt. The surprising findings serve as indicators of how this inimitable slice of the business world stands apart.

FAMILY FIRSTIn hindsight, families should have gotten acclaim beyond the box office for their business skills. After all, family owners are highly incentivized to pay attention: on average, family owners have held their shares for more than 78 years, and have 69 percent of their personal wealth invested in the firm. They have a vested interest in ensuring that the managers running their companies are protecting their assets.

Anderson and Reeb proved that despite their bumbling portrayal in the media (see: the Bluths of HBO’s Arrested Development), family firms are more valuable than diffusely owned firms, which are held by a large number of shareholders and investors.

Family businesses are also highly prevalent. Thirty-five percent of Fortune 500 companies and 60 percent of publicly held companies in the US are family-controlled, according to the advocacy group Family Enterprise USA.

It turns out family presence cannot be ignored. Just as overbearing families tend to weigh in on deci-sions “for our own good,” firms with actively engaged

family owners generally outperformed firms without an active family member. Decades after public firms’ initial offerings, many family members continue to hold hands-on positions in day-to-day operations.

The findings ignited a flurry of attention from academic and mainstream media, including a Businessweek cover story. For Anderson, the next questions quickly took shape: Why are these firms more valuable—and under what circumstances?

NOW YOU SEE ME…In their recent article in the Journal of Financial Economics, the pair invited Associate Professor Augustine Duru to study the effects of corporate transparency on family firms. Thanks to his prior research on the use of accounting information in CEO compensation, Duru had expertise in measuring transparency through an accounting lens.

Like many others, Duru had initially assumed that family firms would be less valuable than diffusely owned firms. “But my colleagues’ empirical work showed that, certainly, family firms were more valuable. It seemed counterintuitive,” Duru said.

Past research has demonstrated that corporate transparency is crucial in order to protect share-holders and mitigate conflict between large and small investors. But no one had studied transpar-ency specifically within the context of family firms.

“When they decided to bring in the accounting perspective,” Duru noted, “the question became: If we believe that accounting information is important to firm performance, what would happen if there was a lack of information?”

While all publicly traded firms must comply with mandatory accounting disclosures, the authors acknowledge that there is still substantial variation in what firms choose to reveal—as well as in the amount of outside scrutiny they receive. Firms can also elect to engage in voluntary disclosures.

“Transparency is clearly a choice; there are public companies that are not as transparent as they could be,” Anderson said. “But some of it is market-driven, and some of it is shareholder-driven as well.”

To test their theories, the researchers built an index that ranked the opacity of the largest 2,000 US firms. Family involvement was defined as firms in which the founders or heirs maintain influence, usually through an equity stake. About 22 percent of the firms in the sample were founder-controlled, and another 25 percent heir-controlled.

Opacity was categorized using four factors that indicated the levels of both internal and external opacity:

• Trading volume and bid-ask spread, which lend insight into the amount of information uncertainty

• Analyst following and analyst forecast errors, which help explain the availability of firms’ information

The researchers determined that both types of family firms are significantly more opaque (by about five percent) than diffuse shareholder firms. “Their shares trade less than those in diffuse shareholder firms and exhibit significantly less analyst following,” they wrote.

Analysts are important because they play a monitoring role. Large, publicly traded multina-tional firms are subjected to scrutiny; “multiple monitoring” keeps controlling families on their best behavior, just as the looming threat of the Five Families did in the Godfather’s world.

How does opacity impact other shareholders’ wealth, beyond the family? Since family firms are more valuable—and tend to be more opaque—then was opacity more valuable?

The opposite was true.

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

11

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

10

“THERE APPEARS TO BE A LOT MORE INFORMED TRADING GOING ON IN FAMILY FIRMS; GIVEN THE MAGNITUDE OF IT, SOME OF IT IS LIKELY ILLEGAL.” RONALD ANDERSON, PROFESSOR

JUST AS OVERBEARING FAMILIES TEND TO WEIGH IN ON DECISIONS “FOR OUR OWN GOOD,” FIRMS WITH ACTIVELY ENGAGED FAMILY OWNERS GENERALLY OUTPERFORMED FIRMS WITHOUT AN ACTIVE FAMILY MEMBER.

WMT 1.95M@ 62.11 0.50...DELL 6.21M@ 17.93 0.31...CCL 3.09M@ 30.58 0.16...CPB 455K@ 31.73 0.35...COLM 135K@ 49.30 0.04

COVER STORY BLOOD IN BUSINESS

Where a positive relationship existed between family ownership and performance, it was limited to firms with a high level of corporate transparency. When the corporate information environment was opaque, however, family firms ceased to be as valu-able as firms without family owners.

“When it’s harder to see what’s going on inside the company, it is much harder for the market to monitor the family, and as a consequence maybe the family can misbehave,” Anderson said. Opacity reduces the ability of outsiders to police opportunism by family firms. Simply put, the top-performing family firms are also the most transparent.

Think Walmart. The Walton family’s massive multinational is currently followed by 36 analysts, all of whom are listed on the Walmart website, along with extensive stock information, historical pricing, and governance documents. The world’s largest retailer is also covered widely in the news media. For Walmart, there is no escape from scrutiny.

The researchers also looked at CEO types in these transparent top performers. In their sample

• the original founders held the top spot 37.7 percent of the time;

• outsiders, like Campbell Soup Co.’s Denise Morrison, 34.2 percent; and

• heirs, such as Nordstrom Inc.’s Blake Nordstrom, 28.1 percent.

Transparent family firms led by an outsider performed best, followed by those led by founders and then heirs. Yet all three types of these trans-parent family firms still outperformed transparent, diffusely owned firms.

In the absence of a highly transparent environ-ment, there was no evidence of a benefit attributable to family ownership. In fact, in more opaque family firms, there was a negative relationship: as opacity increased, performance fell. Opaque family firms performed worse than any other type of firm. In those muddy waters, families can exploit control to extract private benefits at the expense of smaller investors.

It’s clear that shareholders—and thus the S&P—value founder or heir involvement only when those family values include financial transparency.

TAKE THE CANNOLIAs it turns out, informed trading may also be a family affair. And when there are short sales, there’s gonna be trouble.

Anderson’s latest project, with coauthors Reeb and Wanli Zhao of Worcester Polytechnic Institute, finds that family firms boast “substantially higher” volume of abnormal short sales, where traders bet on a company’s poor performance.

“There appears to be a lot more informed trading going on in family firms; given the magnitude of it, some of it is likely illegal,” Anderson explained.

Prior studies have found that family owners are among the best informed of shareholders. Anderson postulates that this is attributable to a few factors. For instance, they are likely to know about skeletons in the family closet. Also, family members who do not serve in senior management at the firm can fly under regulators’ radar more easily, and potentially avoid detection.

Of course, outside investors could play a role in these antics by gleaning information from a family member and using it for personal benefit. Or perhaps the short sales are a product of disgrun-tled employees who perceive family domination as hurting the firm.

Take the case of Robert Chestman, a stock-broker convicted on insider trading charges following the 1986 takeover of Waldbaum Inc., a New York-based grocery chain now owned by the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) asserted that Mr. Chestman had received nonpublic information from a member of the Waldbaum family, which he used to trade 11,000 shares of company stock.

But Chestman was by no means the only one selling. In the days before the company’s announce-ment, the trading volume in Waldbaum stock skyrock-eted. In two days, trading climbed from 2,300 shares to more than 77,000 shares traded daily, according to The New York Times and the SEC.

Insider trading hardly capped in the 1980s. In 2005, former senator Bill Frist, heir to the for-profit hospital chain HCA, raised the SEC’s ire. The commission conducted an 18-month investigation into Frist’s sale of his blind trust of HCA shares, but ultimately did not press charges. Frist ordered the sale during a peak in the stock’s trading; weeks later, a less than stellar earnings report drove the share price down by nine percent, according to USA Today.

THE VALUE OF DISCRETIONInformation leakage was at the center of Anderson’s study. At the root of short sales is the spread of nonpublic information. By identifying and homing in on the times when short sales preceded negative earnings surprises, the researchers made the issue empirical. The question: Does family presence aid or impede informed trading?

They analyzed short sales that occurred prior to earnings surprises, merging the SEC’s short-sales database with their own information on family ownership in the largest US firms. The resulting sample was 1,571 strong, with family firms making up more than one-third of the sample.

Rather than focusing on the motivation of the sellers, the researchers simply sought to uncover whether insider trading was more prevalent in family firms.

It was. “Family firms experienced almost 17 times more abnormal short selling preceding nega-

COVER STORY BLOOD IN BUSINESS

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

1

2

Compiled by Nicole Federica and Jackie Sauter

Founder CEO Michael Dell, Dell Inc. NASDAQ: DELL

Mark Zuckerberg wasn’t the first tech entrepreneur to start a billion-dollar enterprise from a dorm room. Dell began his computer business at the University of Texas in 1984. By 1992, the then-27-year-old had become the youngest CEO of a Fortune 500 company.

Dell has since racked up accolades, written a book on his success, and served on the US President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. Though he stepped down as CEO in 2004, he returned to the position in 2007 at the request of the board of directors. The Texan has four teenage children; perhaps a successor is in their midst? In the meantime, Dell Inc. announced plans to launch its first consumer tablet late this year.

Professional Manager CEO Denise Morrison, Campbell Soup Company NYSE: CPB

Denise Morrison, president and CEO of Campbell Soup Company, hails from a family of successful businesswomen. Perhaps, then, it’s appropriate that she took over leadership of the family-rooted company in August 2011. Morrison is only the 12th CEO in Campbell’s 140-year history, and its first female leader; she joined the company in 2003.

With 35 years’ experience in the packaged goods industry, Morrison started in the sales department of Procter & Gamble, and previously served at Pepsi-Cola, Nestlé USA, Nabisco Inc., and Kraft Foods. Campbell’s has projected net sales growth between 0 and 2 percent in 2012.

Heir CEO Micky Arison, Carnival Cruises NYSE: CCL

Micky Arison is the CEO of Carnival Cruises CCL, the cruise operator that owns brands such as AIDA, Seabourn, Carnival, Ibero, and a series of others. His father, Ted, founded the business in 1972. Micky joined in 1974 and worked his way up to the chairman role in 1990; he became known for acquisitions, including the purchase of Holland America Line in 1989 and P&O Princess Cruises in 2002. The Israeli American also owns the NBA’s Miami Heat.

He’s no stranger to controversy; early this year, the partial sinking of cruise ship Costa Concordia in Italy claimed at least 17 lives, with many more injured or missing. The company said it expected a $175 million hit against net income in fiscal 2012 as a result of the disaster, according to Reuters.

ESTABLISHED 1984

INHERITED 1990

HIRED 2003

RELATIVE LEADERS

tive earnings shocks than nonfamily firms,” the authors wrote. These firms also had marginally fewer abnormal short sales before positive surprises—indicating that more sellers were hanging on to their stock in anticipation of good news.

This was no coincidence. The presence of family members as managers or board members increased the likelihood of short sales. The researchers contrasted family ownership with that of hedge funds, private equity funds, and other large-block shareholders, but did not find the same results.

There are regulatory implications. Despite the researchers’ findings, the SEC’s enforcement actions of late have focused on hedge funds, with 22 enforcements between 2006 and 2008 against the funds, and zero filed against family owners. Further investigation reveals zero enforcements filed against family owners through early 2012.

Certainly, the SEC takes abuse of short sales seriously. The commission has held numerous public hearings, enacted new rules on “naked” short sales, and required more transparency about the short-selling process. The focus on short sales is warranted: the SEC says that short selling comprised almost half of US equities volume, based on data provided by exchanges for June 2010.

“Our analysis suggests that regulations to reduce informed trading, while potentially limiting such activity in nonfamily firms, appear substantially less effective in family firms,” Anderson concluded.

DO ME THIS FAVOROf course, in order for earnings surprises to occur, firms have to play a role in the action. That could mean an acquisition or investing in a new business venture. And the latter often requires firms, and their managers, to borrow money.

Debt can be a tricky business, and all debt is not equal—now that debt is no longer traded in Mafia-style personal favors, that is.

No one knows this better than Associate Professor Parthiban David, whose expertise focuses on the impact of corporate governance on firm performance. David holds the Collins Chair in Strategic Management.

David, along with coauthor Jonathan O’Brien of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, examined how the type of firm debt is related to growth. The pair chose Japanese firms to make up the sample, due to their predilection for growth.

On its face, growth is a noble goal—but there can be too much of a good thing. Excessive growth can harm profits if managers don’t share the resulting wealth with investors, and instead funnel it back into the firm.

Debt helps to keep managers in check: they have to make interest payments, repay the balance at the end of a contract, and face the threat of default. Just as family-owned firms are inherently anchored in relationships, forms of debt can also have a relational quality. And debt plays an impor-

tant, pseudo-parental role in corporate governance. Exhibit A: Bank loans are built on relationships.

Business owners have a rapport with the bankers who invest in the growth of their businesses. Loans are not merely dollars and cents to the bank (or so they would have us believe); rather, banks assess the complete picture of the borrower and company.

They also consider the possibility of ancillary business relationships that might form down the line; loans could be a foot in the door to a more robust, potentially lucrative relationship. Often bank representatives will hold seats on the firm’s board of directors, provide other business services beyond lending, and have relationships with the firms’ customers and suppliers.

“Bank loans are long term,” David said, explaining that both sides build trust and may act as partners. “Banks have business relationships; growth is important to them, because more growth means more business.”

In contrast, bonds are transactional, impersonal forms of debt. Bonds allow lenders to keep their borrowers at arm’s length. These securities are diffusely held, and lenders are focused solely on the returns they earn.

Consider the case of Columbia Sportswear Co., a family-owned business that began selling hats in 1938.

After the 1970 death of the family patriarch, the near-insolvent company struggled to stay afloat; it had already taken a $150,000 loan from the Small Business Administration. Within two years the company racked up a negative net worth of $300,000, according to Funding Universe.

Yet the Boyle family was able to draw more credit from its bank; bank officers even suggested the family consult an adviser, which was the “first step on a path toward stability and then growth,” the owners told Family Business magazine. The infusion of credit happened to pay off; Columbia has come a long way since then, projecting revenues of $1.7 billion in 2011.

SO WHAT’S THE RUB?There is no question that relational debts are benefi-cial to firms that invest substantially in R&D. The long-term relationship between lender and borrower allows continuity of investment; the bank can step in more easily if the firm were to default.

Transactional debt was more effective in preventing overinvestment in firm growth than relational debt. While relational debt may lead to more growth, the growth may hurt profits, David and O’Brien concluded.

This may be best understood with an example—one that’s all too familiar.

In 1980s Japan, stock and real estate markets peaked, and real estate was all the rage. Many firms that previously had never invested in real estate were tempted to get in on the action.

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

1

5

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

14

COVER STORY BLOOD IN BUSINESS

ON ITS FACE, GROWTH IS A NOBLE GOAL—BUT THERE CAN BE TOO MUCH OF A GOOD THING. EXCESSIVE GROWTH CAN HARM PROFITS IF MANAGERS DON’T SHARE THE RESULTING WEALTH WITH INVESTORS... DEBT HELPS TO KEEP MANAGERS IN CHECK.

COVER STORY BLOOD IN BUSINESS

As Northwestern’s I. Serdar Dinc discovered, firms that had relational debt were more likely than those with transactional debt to make real estate investments. When the bubble burst less than 10 years later, they were hurt badly. Parthiban David’s work implies that the “leniency” of those relational lenders led to that overinvestment, which ultimately weakened the firms.

If debt is to be used effectively for corporate governance, then managers—and shareholders, family or otherwise—need to understand the vast differences provided by these two diverging forms of debt.

GO TO THE MATTRESSESDebt was something that J. Willard Marriott detested. When the founder of Marriott Interna-tional wanted to focus on growing Hot Shoppes, the family’s modest restaurant chain, his heir saw the promise of hotels. Getting into bed with the hospi-tality industry meant going into debt, something the elder Marriott avoided at all costs.

“Debt was something that [my father] didn’t understand, and he hated it…he didn’t want anything to do with it,” Bill Marriott once told The Washington Post. Luckily for travelers, J. Willard’s son went to the mattresses for the company, now valued at around $10 billion.

In the first six years after Bill took over the presi-dency, the company quadrupled in size, surpassing Howard Johnson and Hilton Hotels in both revenue and profits. The younger Marriott acquired Big Boy and Roy Rogers restaurant chains, and made the company international with an acquisition in Venezuela. He also invested heavily in research, which informed the decision in 1983 to target the mid-priced hotel market with Courtyard by Marriott.

Still, J. Willard’s conservative business strategies are consistent with Anderson, Duru, and Reeb’s findings from a recent study of the ties that bind family ownership and investment decisions.

The authors examined dueling potential motiva-tions behind investment decisions: an aversion to risk was one possibility, or an extended “invest-ment horizon.” With Duru’s help, the team focused on accounting disclosures required by regulators, including R&D and capital expenditures.

What was the family’s biggest influence?The researchers discovered that family firms

preferred to construct their future in physical assets,

like new restaurants, as opposed to riskier ventures—such as expanding into a new industry segment.

“We found that family firms invested less in R&D; they are more risk averse,” Duru said, explaining that family firms devote less capital to long-term investments than do diffusely owned firms. Compared to their peers, family firms also receive fewer patents per dollar of R&D investment.

Rather, they seem to prefer doubling down on reinforcements that strengthen their core business. Take Carnival Corporation, which has 101 ships among its brands and 10 new ships on order, focusing on expansion into Europe, Australia, and Asia. The Arison family retains 35 percent of company stock in the world’s largest cruise ship operator.

The reluctance to pony up for long-term invest-ments may be counterintuitive. Tales of family business owners often hinge on the notion of their far-reaching view of the future and their financial sacrifices, made to prop up the business. It is possible that there is less spending on R&D in family firms simply because family oversight makes firms more efficient.

TIMES HAVE CHANGEDEfficiency is something that Richard Lenny, the first outsider to serve as CEO of Hershey Foods Company, understood. Lenny increased company profits by closing six underperforming plants in the US and Canada in 2007, cutting 3,000 workers, and outsourcing the production of cocoa.

It was a far cry from the utopian community that Milton Hershey envisioned for his employees and their families. When the Great Depression hit and sales plummeted 50 percent, Hershey did not lay off a single worker, but instead used employees to pursue growth opportunities. His ideals were as popular as his company’s sweets; more than a century later, the town’s identity is still tightly wrapped in silver foil with a tidy bow.

Milton Hershey’s focus on protecting employees was not the norm for corporate America, but it is representative of many Japanese firms, which often increase their investments in growth when demand for their products falls.

“Given a choice between cutting dividends or workers, CEOs there generally say their employees and suppliers are the most important stakeholders,” David said. “It’s almost a family situation.”

The reason behind firms’ diversification—and whether the motivation differed by the identity of its owners—was the focus of David’s recent study.

In the same way that types of debt can be consid-ered either relational or transactional, domestic and foreign owners also display these characteristics.

Prior research on corporate diversification and its implications for firm performance had treated all owners as if they had the same end goal: profit.

Not so, David and his colleagues found, in a paper published by the Academy of Management

in 2010. Diversification is also a means to other ends, such as career advancement opportunities for employees, higher compensation, and lower employment risk.

Using data from four sources, and excluding small firms and those in highly regulated sectors, their sample resulted in 1,180 unique firms.

It turns out that relational owners emphasize growth, while transactional owners emphasize profit for shareholders. The differences are considerable: on a share-per-share basis, transactional owners “are over three times more effective than relational owners in pressuring managers to improve profit.”

“What we found is that when there is more rela-tional ownership, the firms are less likely to cut their wages or lay off people, even when performance goes down,” David said. “But with transactional ownership, they are more likely to do so.”

For domestic owners, he believes, it all comes down to stakeholder relationships. Firm growth means new business, which keeps firm employees and their suppliers working. But firms with foreign ownership are more likely to diversify the business in order to collect more profits.

David was quick to point out that domestic owners are not blindly making poor business deci-sions. “There is a self-interest here also,” he said. “It is not irrational altruism. There is an economic incentive for domestic owners to support growth; once again, more growth means more business.”

The project helped to reframe a central question about firm performance, which previously had been viewed only through the profit lens.

Like his colleagues’ work, the findings from David’s team had significant implications for gover-nance literature.

Taken together, the emphasis that Kogod’s faculty have placed on researching the value of family firms has highlighted the firms’ critical value to the US economy.

Beyond their profitability, family businesses also employ 63 percent of the US workforce. As regulators look ahead to a November election in which the key issue is jobs, they should pay a visit to these firms for counsel on how policy will impact expansion and job creation, said Ann Kinkade, CEO of Family Enterprise USA, in Forbes.

Questions remain. Will the SEC step up its focus on short-sale trading in these valuable firms? Can larger firms in the US gain access to relational funding to fuel firm growth, traditionally a more popular investment choice for small businesses? How can family businesses be encouraged to add jobs?

As Clemenza argued to Michael Corleone, “At least give me the chance to recruit some new men.”

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

16

KO

GO

D N

OW

FALL 2

011

| kogodnow

.com

17

CREATING THE COVER STORY

Academic papers that gave rise to the cover story

Ronald C. Anderson, Augustine Duru, and David M. Reeb, “Investment Policy in Family Controlled Firms,” Journal of Banking and Finance (forthcoming).

Ronald C. Anderson, Augustine Duru, and David M. Reeb, “Founders, Heirs, and Corporate Opacity in the US,” Journal of Financial Economics (2009).

Ronald C. Anderson and David M. Reeb, “Founding-Family Ownership and Firm Performance: Evidence From the S&P 500,” The Journal of Finance (2003).

Ronald C. Anderson, David M. Reeb, and Wanli Zhao, “Family Controlled Firms and Informed Trading: Evidence From Short Sales,” The Journal of Finance (forthcoming).

Parthiban David, Andrew Delios, Jonathan Paul O’Brien, and Toru Yoshikawa, “Do Shareholders or Stakeholders Appropriate the Rents From Corporate Diversification? The Influence of Ownership Structure,” Academy of Management (2010).

Parthiban David and Jonathan Paul O’Brien, “Firm Growth and Type of Debt: The Paradox of Discretion,” Industrial and Corporate Change (2010).

“WHAT WE FOUND IS THAT WHEN THERE IS MORE RELATIONAL OWNER-SHIP, THE FIRMS WERE LESS LIKELY TO CUT THEIR WAGES OR LAY OFF PEOPLE, EVEN WHEN PERFORMANCE GOES DOWN. ” PARTHIBAN DAVID, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR

In two very visible situations, Congress used the Internal Revenue Code to deal with this growing concern. Both times, these provisions were contro-versial; after all, executive compensation has typi-cally been considered a matter to be resolved by corporate boards and executives.

As the debate over tax reform rages on, it is imperative to consider the effectiveness of this approach. The question is, has using the federal tax law to deal with corporate governance issues solved the problem Congress was trying to remedy? We think not.

A BALLOONING PROBLEM In the late 1970s, high-profile executive severance packages, known as golden parachutes, began to unfold. The so-called parachutes triggered substan-tial payments in the event of a corporate acquisition.

One of the first corporations to adopt a para-chute-type arrangement was Hammermill Paper. According to a study on the origins of golden para-chutes by Peer Fiss, Mark Kennedy, and Gerald Davis, the provisions stated that, upon “a change of control,” the executives’ employment by the company shall continue “for at least three years, at an annual rate of compensation equal to his total compensation for 12 months preceding the change.” In other words, Hammermill’s senior executives were guaranteed three full years of salary in the event of a company acquisition.

By the early 1980s, high inflation rates and a depressed stock market led to a wave of corporate acquisitions. Economic conditions simply made it more attractive for companies to grow through acquisition rather than organically.

As the acquisition wave grew, the golden para-chute trend continued to pick up steam. By 1981, “15 percent of the 250 largest US corporations had such plans in place,” according to Organization Science. Congress became increasingly concerned over some of these arrangements.

Members of Congress worried that, in some situations, these arrangements—although board-approved—were hindering corporate acquisitions by increasing the cost of acquisitions and dissuading

interested buyers. Other times, these payments tended to encourage the executives involved to favor a takeover that might not be in the best interests of the company’s shareholders—the very group they were hired to serve. In either event, Congress was concerned that payments to shareholders were being reduced.

PLAN DEPLOYEDCongress decided to deal with the problem by discouraging transactions that would reduce amounts that might otherwise be paid to company shareholders, according to a report by the Joint Committee on Taxation at the time.

How did congressional representatives set about discouraging these arrangements?

By providing that “excess parachute payments” would be nondeductible to the corporation and imposing a 20 percent excise tax on the executive.

What qualified as an “excess” parachute payment? One that was

1. in the nature of compensation (including a non-compete agreement);

2. paid to an officer, shareholder, or highly compensated individual; and

3. deployed only with a change in control of a corporation—but only to the extent that the payment exceeded three times the average amount of compensation the individual had earned in the five years preceding the acquisition.

The effect? An almost immediate increase in parachute arrangements, which until then were still rare—and the introduction of “gross up” clauses, under which companies pay the 20 percent excise tax on behalf of the executives.

Executives who did not have parachute arrange-ments argued that their pay should be consistent with that of their peers. They sought to have para-chute payments added to their compensation arrangements, and many boards agreed.

In our country’s recent history, Congress has tried at times to solve problems on its own, spurred by corporate governance issues that (it felt) were not sufficiently addressed by state laws. Nowhere is this more evident than in executive compensation.

ARTICLE BY DAVID J. KAUTTER & ANDREW R. ZANK

THE KOGOD TAX CENTER IS A NON-PARTISAN CENTER THAT PROMOTES INDEPENDENT RESEARCH ON TAX POLICY, PLANNING, AND COMPLIANCE ISSUES IMPACTING SMALL BUSINESSES, ENTREPRENEURS, AND MIDDLE-INCOME TAXPAYERS.

GOLDEN PARACHUTES GET A LIFT FROM CONGRESS

KOGOD TAX CENTER

Meanwhile, executives who already had golden parachute arrangements fell into two categories:

• First, those with payments that were less than three times their base amount sought, and often received, an increase in the amount of their payments to 2.99 times their base amount. They pointed out that at that level, the payments would still be fully deductible by the corporation (and no excise tax would be imposed on the recipients).

• Those who had parachute payment agree-ments in excess of three times their base amount sought, and often received, “tax gross up” payments. This means that after the gross up payment was received, included in income, and the 20 percent excise tax paid on the gross up amount, the executive received the amount he would otherwise have been left with had there been no excise tax on the underlying payment (see Figure 1).

CRASH LANDINGGolden parachute agreements remain to this day a common part of executive contracts, ensuring about two to three years of salary and bonus, according to a recent Wall Street Journal article. Despite Congress’s effort, golden parachutes are continu-ally being deployed.

In 2011, at least four CEOs of target companies were in line for a payout of more than $50 million, including $100 million to former Nabor Industries CEO Eugene Isenberg; four more CEOs were in line for payouts of more than $30 million; and many more executives expected payouts in the tens of millions.

It seems pretty clear that Congress’s attempt to implement a change in corporate governance to reduce the trend 25 years ago has not discouraged the practice. If anything, these arrangements are more widespread today—and more generous in their terms—than they were when the legislation was enacted.

POLITICAL AIRSIf at first Congress didn’t succeed, it tried again…this time by limiting the deductibility of compensa-tion paid to executives.

In the early 1990s, information on the lack of correlation between executive compensation and economic performance became increasingly avail-able, thanks to the introduction of United Share-

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

19

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

1

8

Company Pfizer Inc.Executive Hank A. McKinnell Jr.Term 2001-2006Payout $188,329,553

There are 21 CEOs who received “walk-away” packages greater than $100 million, according to a recent report from corporate governance consulting firm GMI. Collectively, the top dogs’ total earnings exceeded almost $4 billion. “Too many golden parachutes and too many retirement packages are of a size that clearly seems only in the interest of the departing executive,” the report postulated. Below are a sample of five such payouts in a variety of industry segments: health care, retail, digital, oil & gas, and banking.

Company Target CorporationExecutive Robert J. UlrichTerm 1994-2008Payout $164,162,612

Company eBay Inc.Executive Margaret C. WhitmanTerm 1998-2008Payout $120,427,360

Company ExxonMobil Corp.Executive Lee R. RaymondTerm 1993-2005Payout $320,599,861

Company Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc.Executive E. Stanley O’NealTerm 2002-2007Payout $161,500,000

WALK-AWAY PACKAGES

EXAMPLE OF PARACHUTE PAYMENT WITH GROSS UP

EXCESS PARACHUTE PAYMENT

holder Association Compensation Surveys and increasingly active corporate shareholders.

As more data on executive compensation came to light, public outrage began to sweep the country; by 1992, CEO compensation had become a key presidential campaign issue, as then-candidate Bill Clinton debated incumbent George H. W. Bush for the country’s attention.

As more citizens voiced concern over the contin-uously rising compensation for top executives, and politicians looked to take action, heated debates began in Washington. Some critics argued that certain executives were increasing their own salaries without input from shareholders, and without ties to the company’s economic performance. The high pay, they argued, was unearned.

Others believed that the large disparity in pay between the executives and lower-level employees, as well as a similar disparity between US execu-tives and foreign executives, was inexcusable and clear evidence of the need for federal intervention.

CHANGING AIMIn 1993, Congress responded by enacting Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code. Under this provision, the corporate tax deduction for compensa-tion paid to the CEO and the four other highest-paid executives of a publicly held corporation was limited to $1 million each.

An exception was made for performance-based compensation: to the extent that payments in excess of $1 million in one year meet goals set by the Board Compensation Committee, and are approved by a majority of the shareholders in a separate vote, then the compensation is fully deductible.

The House Ways and Means Committee stated its belief very clearly that excessive compensation would be reduced following this action. With the new restraints on deductions in place, Congress believed it had taken an important step toward pushing domestic corporations to adopt more responsible, performance-based executive compen-sation systems.

Section 162(m) also attempted to introduce a level of accountability that had been missing, by providing opportunity for more shareholder input.

So what happened? A study of the effects of Section 162(m) calculated that between 1992 and 1997, the median compensation for covered execu-tives increased 17 percent, and executive bonus and long-term incentive plans (as well as grants of restricted stock) nearly doubled.

The study, by Tod Perry and Marc Zenner, also showed that many executives with compensation

below $1 million saw pay raises; 75 percent to 84 percent of executives earning $900,000 or below got a salary bump following the implementation of Section 162(m). Perry and Zenner determined that many others, with pay already above $1 million, saw no change at all.

Quite simply, in response to Section 162(m), many corporations locked in fixed compensation for executives right around the $1 million mark and created performance-based bonuses to further compensate executives beyond their fixed salaries.

Congress wasn’t the only injured party. A 2006 study by the Joint Committee on Taxation found that Section 162(m) eliminated millions of dollars in deductions, reducing profits and, in many cases, adversely affecting company shareholders.

The study concluded that, by making perfor-mance-based pay an exception to the $1 million cap, there was a resulting increase in executive compen-sation, and the provision led to more executives looking to manipulate earnings to demonstrate a better earnings pattern and, in turn, earn higher pay.

Although the consequences of the $1 million cap were far from the results Congress had antici-pated, the legislation has increased executive accountability to corporate shareholders.

BAG IT?As these experiences illustrate, trying to implement corporate governance policies through the Internal Revenue Code has, at best, a mixed record.

Using the tax law to encourage (or discourage) behavior has worked effectively in some parts of the economy. For example, enactment of the Research and Development tax credit has been considered successful in encouraging greater research.

On the other hand, corporate governance does not appear to lend itself to a federal tax solution. Yet despite the uneven results with respect to past efforts, when Congress sees other corporate gover-nance issues it believes are not being addressed adequately, it is likely to continue taking matters into its own hands.

An election year in which taxation is a para-mount issue, and former CEOs are vying for the country’s top spot, presents the opportunity to make a choice to stop legislating through changes to the tax code. It has only made the tax law more complicated, interposed the IRS between executives on the one hand and corporate boards and share-holders on the other, and failed to solve any of the problems with which Congress was concerned.

$800,000AVERAGE COMPENSATION PAID DURING PERIOD(BASE AMOUNT / 5)

$3,000,000PARACHUTE PAYMENT

$4,000,000TOTAL COMPENSATION PAID DURING PERIOD

$3,000,000PARACHUTE PAYMENT

$120,000EXCISE TAX (20%)

$2,400,0003X BASE AMOUNT

EXCESS PARACHUTE PAYMENT

ASSUMEFederal Tax 35%State Tax 7%Fed Excise Tax 20%Total Tax Rate 62%

GROSS UP PAYMENT:

Excise Tax: 20% x $600,000 $120,000

Gross Up Payment Calculation: $120,000 ÷ (1 - 62%) $316,000

TAX ON GROSS UP PAYMENT:Fed (35%) (110,600)State (7%) (22,120)Excise (20%) (63,200)Total (196,000)

$316,000 – $196,000

$120,000 (amount needed to pay excise tax)

KOGOD TAX CENTER

2007

$700,000$750,000

$800,000$850,000

$900,000

2009

0

$1M

$1.2M

FIG 1

$800K

$600K

$400K

$200K

2010 20112008

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

21

KO

GO

D N

OW

SP

RIN

G 2

01

2 | kogodn

ow.com

2

0

Of course, the days of overt KGB control are long gone; in today’s Russia, order seemingly prevails over the repression of an earlier era. And yet, more than 20 years after the fall of the Soviet Union, intimidation and corruption against busi-ness owners is rampant.

Media reports estimate that up to 70,000 cases of corporate raiding— reiderstvo in Russian—occur each year. The sophisticated form of white-collar crime involves the seizure and rapid resale of a company or its liquid assets: private firms and businesses are dismembered, and the parts sold to the highest bidder.

Valeriy Filatov, a Russian-born US citizen and BSBA ’12, coauthored a research article analyzing the phenom-enon with Claudio Carpano, a former executive-in-residence. His research discovered that the annual financial gains made from Russian raids were estimated at a whopping $4 billion in 2010.

“Raiding is mainly performed by bureaucrats and mid-size-business owners—those who didn’t do it in time for the first divvying up of the pie during the 1990s,” Filatov asserted, referring to the privatization of state assets after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

In countries with well-established institutions, such as the United States, corporate raids (also known as hostile takeovers) are usually carried out in accordance with strict guidelines. They are used to restore stability and competi-tive advantage to fledgling companies.

In Russia, the reverse is true: the most successful businesses, or those

that have valuable assets in the form of fixed capital or real estate, are at the greatest risk of raiding.

Certainly, capital accumulation after the fall of the Soviet Union was uneven; some benefited more than others. But that's not why such great disparity between the haves and have-nots exists.

Without clear rules of competi-tion and a mechanism for transferring property to more efficient owners, the system never evolved. Instead, a process of negative selection has emerged, where the strongest and most profitable busi-nesses are picked off, stifling growth and damaging the larger economy.

In Vladimir Putin's Russia, where the power hungry politician was recently elected to a third presidential term, the clout of the bureaucrat—not the wealth of the owner—guaranteed ownership of an asset. “It’s difficult to change duplicitous legal and political systems in an environ-ment that rewards those who exploit it,” said Filatov.

SYSTEMIC RISKIn 2009, Evgeniy Konovalov, the owner of an agricultural company in southern Russia, found himself in pretrial deten-tion. Though the charges were fabri-cated—it was eventually proved in court that forged documents were used to purchase his firm—he spent a year under arrest. During this time he fought the raid executed by his long-time business associate and was eventually named the rightful owner. His business was returned to him in 2011.

“Despite overwhelming evidence of

violations of Russian law by [Konovalov’s business associate], his accomplices, and complicit government officials, none of the parties have been punished,” Filatov wrote in his award-winning paper.

Similar stories abound. “It used to be gangsters who ran

rackets, and now it’s consultants and lawyers wearing ties, who are civilized on the surface but carry out the same black-mail,” Andrei Girev, the general director of a Russian cell phone company, told Bloomberg Businessweek.

One in six Russian businessmen has been prosecuted for an alleged economic crime over the past decade, according to The Economist—most at the hands of corrupt police, prosecutors, and courts.

“The Russian legal system is extremely complex and full of contra-dictions,” Filatov said. “Almost everyone in business is breaking the law on a daily basis, so it’s easy to leverage the law in support of illicit activities.”

While Russian law no longer allows for pretrial sentencing in economic cases, as in Konovalov’s case—this changed in 2010—the surprise element hinders business owners’ ability to fight well-organized, authority-backed raids.

Filatov believes that corporate raiding is under-reported and unaddressed for a slew of reasons: law enforcement doesn’t want to appear incompetent, the media attempts to remain impartial, and the government is disinterested or too corrupt to seek reform.

Another reason the Russian govern-ment is not focused on creating good conditions for private businesses? The

ARTICLE BY ANNA MIARS

RUSSIA’S CORRUPT FREE MARKET

In Russia, corporate raiding is simply the latest incarnation of property redistribution. The tactics have modernized over time: the use of hired muscle in the days of racketeering has been replaced by exploitation of legal loopholes and loose regulations. But the participation of government officials, which makes the whole system possible, remains intact.

profit gap between state-run oil and natural gas companies and other indus-tries. High tax rates on oil and natural gas provide a majority of the country’s budget revenue, making the independent busi-ness community a distant second priority.