Kogalniceanu - Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery of Cernavoda

-

Upload

raluca-kogalniceanu -

Category

Documents

-

view

30 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Kogalniceanu - Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery of Cernavoda

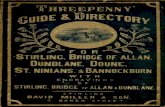

BAR International Series 2410 2012

Homines, Funera, Astra Proceedings of the International Symposium on

Funerary Anthropology 5-8 June 2011

‘1 Decembrie 1918’ University (Alba Iulia, Romania)

Edited by

Raluca KogălniceanuRoxana-Gabriela Curcă

Mihai GligorSusan Stratton

Published by

ArchaeopressPublishers of British Archaeological ReportsGordon House276 Banbury RoadOxford OX2 [email protected]

BAR S2410

Homines, Funera, Astra: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Funerary Anthropology. 5-8 June 2011, ‘1 Decembrie 1918’ University (Alba Iulia, Romania)

© Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012

ISBN 978 1 4073 1008 4

Cover image: Alba Iulia-Lumea Noua - Human Remains. Trench III/2005, Square B (-0,70-0,80m). Foeni cultural group (4600-4500 BC). Copyright Mihai Gligo

This work was possible with the financial support of the Sectorial Operational Program for Human Resources Development 2007-2013, co-financed by the European Social Fund, under the project number POSDRU/89/1.5/S/61104 with the title ‘Social sciences and humanities in the context of global development -development and implementation of postdoctoral research’.

Printed in England by 4edge, Hockley

All BAR titles are available from:

Hadrian Books Ltd122 Banbury RoadOxfordOX2 7BPEnglandwww.hadrianbooks.co.uk

The current BAR catalogue with details of all titles in print, prices and means of payment is available free from Hadrian Books or may be downloaded from www.archaeopress.com

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D

81

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D. Contextual analysis

Raluca Kogălniceanu Muzeul Judeţean „Teohari Antonescu”, Giurgiu, Romania

Abstract The adornments found in the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă during the middle of the last century captured the imagination of many researchers. They were considered to be very numerous and spectacular. For this study we have gathered as much of the data available today as possible. We studied artefacts that form part of the archaeological collections of two institutions in Bucharest (the Institute of Archaeology and the National Museum of History of Romania). To this, we added all the data we could find from the preserved field notes and drawings and on the yearly excavation reports and syntheses on the Hamangia culture, and tried to corroborate these findings with the anthropological analysis of the human remains. The result of this combination of sources is presented in a table (see Appendix) that formed the basis of our attempt to contextualize the findings. Key words Cernavodă, Hamangia culture, adornments, contextual analysis Introduction Adornments represent one of the most important categories of grave goods. They were extensively analysed and, for the Neolithic period, a special attention was given to those made of shells (Comşa 1973; Schuster 2002; Chapman 2003; Tripković 2006; Dimitrijević and Tripković 2006; Voinea, Neagu and Radu 2009; Séfériadès 2010; Ifantidis and Nikolaidou 2011). These artefacts are characterized not only by their functional value, but also by their decorative and symbolic values. The artefacts made of Spondylus or marble were generally considered as prestige goods due to the exotic nature of the raw materials they were made of. The Hamangia cemetery from Cernavodă (Figure 1) was excavated in the 1960s. Its full publication remains an aspiration, the only published data being the annual excavation reports (Morintz, Berciu and Diaconu 1955; Berciu and Morintz 1957; 1959; Berciu, Morintz and Roman 1959; Berciu et al. 1961) and other general references in volumes of synthesis (Berciu 1966; Haşotti 1997). In spite of the fragmentary information and materials available1, we consider that the results obtained so far are significant enough to try an analysis of these important discoveries.

1 Some pieces, not included in the analysis, might be part of the collections of the National History and Archaeology Museum in Constanţa.

Figure 1. Map of Romania with the location of the Cernavodă

cemetery. Analysed material For this study we used the pieces found in the archaeological collection of two institutions in Bucharest: “Vasile Pârvan” Institute of Archaeology – Berciu Fund and the National Museum of History of Romania. Additional data extracted from the preserved excavation field notes and plans2, from the manuscript of the anthropological analysis3, and from the annual excavation reports and synthesis mentioned previously were added to the data obtained from the direct analysis of the above mentioned artefacts. The corroboration of these various sources led to the numeric differences between this study and the one of Monica Mărgărit in this volume. A table presenting briefly all the adornments identified so far from all the sources available and mentioned above can be found in the Appendix of this study. Typology of the artefacts according to their shape (Figure 2) The most common category is that of beads, made of Spondylus and marble. These took various shapes: tubular (66 pieces) (Figure 3.1), biconvex (or barrel-type – 12 pieces) (Figure 3.2 – the ones near the tubular bead), cylindrical (10 pieces) (Figure 3.2 – the ones at the extremities of the string and Figure 3.3) and

2 In the archive of “Vasile Pârvan” Institute of Archaeology, Bucharest – Berciu Fund (Berciu 1954; 1955; Morintz 1954; 1954-1955; 1955; 1956). 3 In the archive of the Center of Anthropology of the Romanian Academy, Iaşi branch (Necrasov et al. 1981).

Raluca Kogălniceanu

82

trilobite (3 pieces) (Figure 3.4). It is highly possible, as noted by M. Mărgărit (see her study in this volume), that the tubular beads came from broken bracelets, while the cylindrical ones were originally tubular beads that suffered deteriorations, indicating a long and intensive use of these artefacts. The wear traces noted on these pieces confirm the long use, thus strengthening the symbolic value attained by these adornments. Another category is that of the bracelets, made of Spondylus and marble (Figure 4). Although we managed to find data regarding only six pieces, their number must have been larger. They were discovered both as complete pieces and as fragments. Two sub-types could be individualized so far: the wide, slightly inclined ones (Figure 4.1 and 4.2) and a narrower and straighter model (Figure 4.3). Another type of adornment considered, over time, as either bracelet fragment or pendant is that of the perforated plates (Figure 5). The one that could be analysed directly was made of Spondylus. They have rectangular shape and three or four perforations at the corners. They could come from repaired bracelets or from bracelets made of one or more such plates. The low number of such pieces (only three disparate pieces were identified at Cernavodă) might suggest that this last hypothesis is unlikely. They might also have been

part of composite adornments such as necklaces, earrings, hair jewellery, etc.

Figure 2. Typology of the adornments according to their shape.

1

2

3

4 Figure 3. Spondylus and marble beads. 1: tubular (IAB, Berciu Fund, inv. no. F 2); 2: tubular, cylindrical and barrel type (MNIR, inv.

no. 11674); 3: cylindrical (IAB, BF, inv. no. F 38); 4: trilobite (IAB, BF, inv. no. F 36) (Photos: G. Chelmec – 1, 3 and 4, and M. Mărgărit – 2).

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D

83

1

2

3 Figure 4. Spondylus and marble bracelets. (1: MNIR, inv. no. 11666; 2: IAB, BF, inv. no. F 41; 3: IAB, BF, inv. no. F 84)

(Photos: R. Kogălniceanu – 1, G. Chelmec – 2 and 3).

Figure 5. Spondylus perforated plate (IAB, BF, inv. no. F 340)

(Photo: G. Chelmec).

1

2

3

4 Figure 6. Spondylus and marble pendants. 1: fang shape

(IAB, BF, inv. no. F 26); 2: rounded cruciform (MNIR, inv. no. 11668); 3: anthropomorphic (IAB, BF, inv. no. F 6);

4: anthropomorphic (not found, Berciu 1960, fig. 9.1) (Photos: G. Chelmec – 1 and 3; R. Kogălniceanu – 2).

Raluca Kogălniceanu

84

The cemetery did not lack pendants, made of Spondylus and marble. Although we only have data for six items of this type they are surprisingly different in shape. One of them is curved, imitating an animal fang (Figure 6.1), another one has a purely geometrical shape (rounded cruciform; Figure 6.2) and two others have strong spiritual connotations given by their anthropomorphic shape (Figure 6.3 and 6.4). We have information for only one discovered ring, made of bone, (Figure 7), but it is not impossible that there had been more of these items.

Figure 7. Bone ring (IAB, BF, inv. no. F 39)

(Photo: G. Chelmec) As some of the adornments mentioned so far might also have been used to decorate clothing, we considered it fitting to also mention the two buttons, one made of Spondylus (Figure 8.1) and one made of stone (Figure 8.2), discovered in the Hamangia cemetery.

1

2 Figure 8. Spondylus and stone buttons (1: IAB, BF, inv. no.

117; 2: IAB, BF, inv. no. F 014) (Photos: G. Chelmec)

The typological variety of adornments is not very rich, being limited to only several large groups (beads, bracelets, perforated plates and pendants) to which the ring and the buttons are isolated supplements. More variety is to be met inside each typological category. At least four types of beads, two types of bracelets and three types of pendants can be enumerated. Compared to the findings from the cemetery of Durankulak (our only source of good comparison), it can be said that the adornments from the cemetery of Hamangia are far less numerous and diverse. Raw materials used Five distinct materials were used to produce the adornments (Figure 9). Most of the pieces were made of shell valve. Because we did not have access to all the artefacts discovered in the cemetery, we cannot say if the shell adornments were made of only one or more genus of marine shells, but in all of the cases where a direct analysis was possible it was confirmed that the valves of Spondylus sp. were used. Shells were used to make beads of various shapes, bracelets, perforated plates, pendants and one of the buttons. The frequency of use of shell valves as raw material is visible not only in the number of adornments that were made of it, but also in the fact that almost all types of adornments were made of shell, the only exception so far being the ring, made of bone.

Figure 9. Typology of the adornments according to the raw

materials they were made from. Another quite frequently used raw material was marble (sugar type). At least one tubular bead (Figure 3.1 – first bead on the first row), a bracelet (Figure 5.1) and three pendants (Figure 6.2-4) were made of this material, but there might be more of them as sometimes we noticed that in the case of smaller items at least the marble was confused with Spondylus due to similarities in colour and sometimes even texture obtained after processing the raw material.

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D

85

Other materials were used occasionally, such as copper for a small round bead, bone for a ring and stone for a button. For a better overview on the adornments we made a graph illustrating the type of material used in correlation with the type of adornment (Figure 10). It

can be seen that the most frequent alternation between materials is that between shell (so far Spondylus) and marble (for beads, bracelets and pendants) followed by Spondylus / copper (for beads) and Spondylus / stone (for buttons). A raw material that seems to have been exclusively used for a specific type of adornment is bone, used for making a ring.

Figure 10. Graph illustrating the correlation between the shape of the adornments and the raw material used.

1 2 Figure 11. Marble and Spondylus anthropomorphic pendants discovered inside the cemetery at Cernavoda (1) and inside the settlement at Cheia (2) (for b: Voinea, Neagu and Radu

2009, Pl. 3/1). The raw material issue should also be discussed from a second perspective, which is that of copying a specific type of adornment in one material to another. As we have already showed, tubular beads and bracelets were made of both Spondylus and marble (Figures 3.1 and 5.1-2). To the question of which is the “original” and which is the “copy” we can respond easily in the case of the bracelets. The Spondylus bracelets have a particular shape, broad and slightly inclined to one side, due to the shape of the shell valve (Dimitrijević and Tripković 2006, fig. 2). The marble bracelet could

have taken any shape, slim, straight, etc. but the particular shape of the bracelets made of Spondylus was preferred. Another interesting pair is that of the idols-pendants. One such piece, made of marble, was discovered at Cernavodă. Another almost identical piece, made of Spondylus, and found in the Hamangia settlement from Cheia (Voinea 2010), seems to complete the series of “doubles” made of Spondylus and marble (Figure 11). Another case of copying Spondylus adornments in a different material is that of the buttons. Two buttons were discovered at Cernavodă, one made of shell and the other of stone (Figure 8). An interesting case of imitation is that of the Spondylus pendant in the form of an animal fang. The issue of imitation or copying of Spondylus pieces into other raw materials has not been very well addressed by researchers, who have tended to mention the fact without developing the subject. An interesting classificatory approach to the imitation of objects traditionally or initially made of one raw material in a different material was published not very long ago (Choyke 2008). Although the cases noted at Cernavodă do not fit very well into the categories proposed in the cited study, some readjustment of the proposed typology and some suggestions for the interpretation of

Raluca Kogălniceanu

86

discoveries can be formulated here. We seem to have three categories of imitation at Cernavodă: 1. the imitation of an object made of rare and precious raw material into another rare and precious material. In this category fall the bracelets and the beads made of marble and resembling the Spondylus prototype. Some researchers talk about a “hunger for white jewellery”, especially in relation to the marble pieces of adornment that towards the end of the LBK culture gradually replaced the Spondylus pieces. Spondylus, although typical at the beginning of the culture, might have gone “out of fashion” (or out of reach) towards its end, while locally excavated marble took its place, retaining the same symbolic significance (John 2011, 44). We are not sure we can speak of a wish to reproduce white jewellery, as it is very possible that in their first moments of use, the Spondylus pieces might have exhibited the colour specific of the shell, mostly reddish, as seen on the trilobite beads presented here. As marble is still not an easily available local raw material the copying of Spondylus pieces in marble could be interpreted as another way to express status and ethnic identity in a similarly precious material. As Spondylus was used before marble, maybe the marble pieces imitated the shape of Spondylus artefacts in order to claim the same value. Marble deposits are known in Bulgaria, south of the Stara Zagora Mountains4. It is still far away as a source of raw materials, but it is closer than the Aegean Sea (the source place for Spondylus). The completion of Spondylus bead strings with beads made of marble or lime and the copying of also other larger items from Spondylus to marble shows, according to Siklósi and Csengeri (2011, 57), both the importance and value of Spondylus and that the long-distance was gradually replaced by (or at least supplemented with) shorter-distance trade. 2. the imitation of an object made in non-precious material into a precious and rare raw material. In this category would fall the Spondylus pendant imitating an animal fang. This type of imitation might suggest a transformation of the symbology employed. The Hamangia burials at Cernavodă seem to have a number of characteristics that bring them close to some Mesolithic burials (Kogălniceanu 2009, 85). The use of animal fang pendants in hunter-gatherer communities was a symbol of prestige. Hamangia communities, who were agricultural, might have re-used an older symbol of prestige by giving it a new value through the rare raw material employed. 3. the imitation of an object made of rare and precious raw material into a locally available common raw material (or the other way around). In this category would fall the stone and Spondylus buttons. It is difficult to say which is the “original” is and which the

4 Information from P. Leshtakov (Institute of Archaeology with Museum, Sofia), whom we thank.

“copy” is. As we previously showed, from the few other buttons reported so far in the Balkan area, two were made of Spondylus, one of stone and for two others the raw material is unidentified. If the originals are the Spondylus items, then copying them in stone would simply suggest an attempt to claim a status that was not real. If the original are the stone made ones, using Spondylus made ones would also be about claiming a status, but this time a real owned one. The reuse of some of the artefacts Spondylus was a rare, precious material that, most probably, was not easily available. The scientific community still discusses if local fossil Spondylus was used in certain areas (which would mean easier access to the raw material), but so far no definite conclusion has been reached. There is also no definite proof, no workshop, for the local production of the large Spondylus objects. The only reported primary workshops are in the Aegean area (Dimitrijević and Tripković 2006, 249). There is one slightly later discovery at Hârşova – Tell (Gumelniţa culture, A1 phase) of a small, secondary, workshop. The pieces of Spondylus found there were not new, unworked valves, but pieces of broken bracelets and beads. This led the author of the discovery to draw the conclusion that this workshop specialised in transforming broken, damaged pieces in something that could be of further use. More specifically, this discovery illustrates a workshop that specialised in transforming broken bracelets into beads (Comşa 1973, 66-67). Even though such a discovery has not yet been made for the Hamangia culture, the fact remains that there seem to be indications that once an object made of Spondylus was damaged, the pieces were not thrown away, but an attempt was made to transform them in some other piece of adornment. Larger tubular beads were possibly made of broken bracelets; smaller cylindrical beads were made of larger tubular beads, and so on. It was not only Spondylus objects that underwent this reshaping for further use, but also the marble ones. A possible example could be the marble anthropomorphic pendant (Figure 6.4) that is believed to have come from a former bracelet due to the curved shape of its profile (Berciu 1960, fig. 9/1, 434; 1966, 104). Analogies The analogies that we are looking for come from the Balkan area and the reason for this is that we are trying to see how commonly encountered the adornments found in the Hamangia graves excavated at Cernavoda are, and how they fit into the surrounding context. This context is first of all represented by other Hamangia discoveries, to which we can add the discoveries attributed to the neighbouring and partially contemporary Boian culture. In the end, whenever possible, we have indicated if a certain type of adornment was known even from later contexts of the same area, those commonly attributed to the Gumelniţa and Sălcuţa cultures.

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D

87

The tubular beads were used for a long period of time. They were discovered in the Hamangia area both in cemeteries (at Cernavodă, Durankulak, Limanu) and in settlements (at Ceamurlia de Jos, Cheia), although discoveries made in the settlements are more rare and less rich (Voinea, Neagu and Radu 2009, 11-12). They were generally made both of Spondylus and Dentalium valves (at Durankulak) or Spondylus and marble (at Cernavodă). The discoveries made at Durankulak show that these types of beads were used throughout the entire duration of the Hamangia culture. Such beads were also discovered in Boian and Gumelniţa contexts, with most of these discoveries coming from graves (Comşa 1973; 1974; Beldiman, Lazăr and Sztancs 2008). The same observation is valid also for the bi-convex (barrel) type beads and for the small cylindrical ones (Schuster 2002). Marble imitation of the beads was reported at Durankulak, in two graves (299 and 673; Todorova 2002, Teil 2), and also in a Boian grave at Cernica (grave 101; Comşa and Cantacuzino 2001, 45). An interesting appearance is that of the trilobite beads. They are quite frequent in Boian graves, in their bilobite or trilobite form, such as those discovered at Cernica (Comşa and Cantacuzino 2001), Sultana – Valea Orbului (Şerbănescu 2002), Popeşti (Şerbănescu 1999), Andolina (Comşa 1974, 173-174) and also in the settlements (Boian A and Glina; Comşa 1974, 172-174). But so far they have not been encountered in contexts attributed to the Hamangia culture. For the three beads presented here we have no clear data regarding the context of their discovery. They were found in the boxes labeled “Cernavodă” from the archaeological collection of the Institute of Archaeology in Bucharest. As Boian pottery fragments were reported in the Hamangia cemetery from Cernavodă, the possibility of these beads also being imported cannot be excluded. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of misplacement of these beads sometime during the 60 years that have passed since the excavation of the Hamangia cemetery. Small round copper beads, rare as they are during the Late Neolithic, were also found in the Hamangia cemetery from Durankulak. They were reported in four graves (611, 626, 643, and 648), attributed to the Hamangia I-III phases (Dimitrov 2002, 157, 159). Their presence was also noted in the early Boian cemetery from Cernica, in five graves (95, 120, 340, 342, 355) (Comşa and Cantacuzino 2001), and 28 copper beads of unmentioned shape were found in a grave excavated at Andolina (Boian culture, Vidra phase; Comşa 1974, 173, 203). In the case of the Hamangia graves from Durankulak, these copper beads were found mostly (3 of 4) in male graves, while the situation in the Boian cemetery seems to indicate a female preference for these adornments (3 out of 50). The large Spondylus bracelets represent a quite common find in all Hamangia cemeteries excavated to

date. They are present at Cernavodă and also at Limanu and Mangalia (Comşa 1973). They are also frequent in the Hamangia graves from Durankulak (Todorova 2002, Teil 2). Only two such bracelets were noted in the Boian graves from Cernica; the reason for this could be a preference of the Boian community for the narrow bracelets, possibly made of Glycymeris shell. The narrower bracelets, with a rounder section, have so far been reported at Agigea (Berciu 1966, 81, fig. 41) and Durankulak (Todorova 2002, Teil 2), but they appear to be more rarely used than the wide ones. The marble imitations of Spondylus bracelets are not unique to our area of interest. They are reported at Mangalia (Volschi and Irimia 1968, 57) and Durankulak (298 and 606; Todorova 2002, Teil 2), but they remain a rare appearance. It should be mentioned that wide shell bracelets were encountered even during later periods, such as Gumelniţa culture, although apparently less frequently than previously (Comşa 1973, 65). The rounded cruciform marble pendant might have an analogy in the Boian A settlement from Vărăşti – Grădiştea Ulmilor, but made of Spondylus shell (Boian culture, Vidra phase; Comşa 1974, 174). The analogy is not completely certain as there is no image (photo or drawing) of this pendant, only a written description of it. The anthropomorphic pendants, especially the marble one, have several analogies, made of Spondylus shell, in the graves from Durankulak (108, 609, 621, and 644). They all seem to come from Hamangia III graves (Vajsov 2002, fig. 255; Todorova 2002, Teil 2). Pierced animal tooth pendants are not uncommon during the Prehistory of the Balkan area. But, so far, we could not find an analogy for the imitation of such a piece in Spondylus or in another material from the area of our interest. Buttons were found in few other sites. At Sultana – Valea Orbului and Popeşti (both sites attributed to the Boian culture), four buttons were reported, two at each site. These discoveries come from burial contexts, but unfortunately there is no mention of the raw material these buttons were made of (Şerbănescu 1999, fig. 1; Şerbănescu 2002, fig. 10). A Spondylus button was found at Durankulak, in grave 616 (Gumelniţa A1 phase) (Todorova 2002, Teil 2). Lastly, another report of two buttons, one made of Spondylus and one of marble comes from the settlement Cuptoare – Dealul Sfogea (Sălcuţa culture) (Radu 2002, 169). Finally, rings are known from various Hamangia sites: made of bone at Medgidia – Cocoaşă (Haşotti 1997, 47) and Durankulak (grave 662; Todorova 2002, Teil 2) and of Spondylus at Limanu (Volschi and Irimia 1968, 80, 84, fig. 59). Bone rings are quite frequent in the Boian cemetery excavated at Cernica (Comşa and Cantacuzino 2001).

Raluca Kogălniceanu

88

Analysis of the context of discoveries The position of the adornments in relation to the body of the deceased Unfortunately, there is little data regarding the exact location of the adornments in relation to the deceased’s body, and this reduces the possibility of determining how these pieces were used and worn. Quite often, the pieces were discovered in the area of the cemetery without being part of a particular grave or of a closed complex (such as pits). Nonetheless we can provide some insight. It is difficult to infer how the beads were employed, if they were part of necklaces or bracelets, or if they were part of composite pendants or sewn on pieces of clothing. Most probably, as indicated by the discoveries made at Durankulak (Todorova 2002, Teil 2), they were used in all of these ways. As they are items of small dimensions, they were most certainly part of composite adornments where the number, shape and colour of the small pieces created a whole. This is the explanation for the large number of tubular beads that, although they were considered individually for this study, almost certainly contributed to a much smaller number of composite adornments.

The data that we have so far seem to suggest that, in most cases, the beads were used to decorate the upper part of the body (see Appendix). Most of them were found in the skull and neck area. Some of them were found near the left humerus and right forearm. There is also one drawing in which tubular beads were placed at the feet of one of the deceased. But, on the drawing in which these pieces appear, at the feet of the deceased one can observe another two fragments of long bones, probably from a different individual, which makes the placing of the beads in relation to a particular body questionable. They might also come from a disturbed complex. For some of the beads we do not have any information regarding the context of their discovery. For several beads we know that they were discovered in the prehistoric layer, outside any known closed complex, probably moved by rodents. For only one of the bracelets do we have data regarding its position inside the grave, which was “on the belly”. This bracelet is not present in the drawing of the grave but it cannot be ruled out. It is highly possible that it was identified after the drawing was made. As the arms of the deceased seem to be stretched along the body, if the stated location of the bracelet is correct, it might suggest that it was used as something other than a bracelet, maybe as belt accessory. The other bracelets identified so far were either part of disturbed graves or, possibly, of pits with various materials (mostly pottery) and disarticulated bones, or were found in the prehistoric layer, at some distance from any closed complex. For some of the bracelets we do not have any data regarding the context of discovery. The perforated plates were discovered in similarly ambiguous contexts. One of them was found in

association with pottery, two small axes and a bone fragment, possibly human. A second one was discovered in association with disturbed human bones, while the third was isolated, outside any known closed complex. The lack of data regarding the context means any of the previously mentioned modes of wear could be possible. Two of the pendants were discovered in the chest area of the deceased individuals, which suggests to us that they were worn at the neck. A third one was found in the vicinity of a grave, but we cannot ascertain if it belonged to that grave or not. For other three pendants we do not have any data regarding the context of their discovery. Finally, one of the buttons was apparently found isolated, in the prehistoric layer, while for the second, as well as for the bone ring, we do not have any data regarding the context of discovery. Sex and age of the deceased In order to contextualize as well as possible the adornments found in the cemetery we tried to determine, where possible, whether certain types were preferentially used by men or by women (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Graph illustrating the distribution of certain types

of adornments according to the sex of the deceased. We can observe that beads and bracelets were worn by both women and men, with some slight preference for this type of adornment in male graves. In exchange, the only perforated plate that could be associated with human remains seems to have belonged to a woman. In the same manner, three of the pendants were associated exclusively with male graves. The large number of artefacts that could not be associated with human remains, or for which we lack data regarding the context of discovery, make the above assertion provisory and it is liable to modification in light of future discoveries.

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D

89

It must be said that there seem to be regional rules for the preferential use of certain items in relation to the sex or age of the deceased. For example, in LBK cemeteries there seems to be a preference to use buckles and bracelets in male graves and medallions only in female graves, and this opposition relates to the use of the upper valve of the shell to make the buckles and the lower one for medallions (John 2011, 44). In other cases, such as the Middle and Late Neolithic cemeteries from the Carpathian Basin, the use of the upper or lower valve seems to have been determined by chronological (and regional) factors (Siklósi and Csengeri 2011, 50-51). But, for our purpose, a comparison with the only extensively published and analysed Hamangia cemetery from Durankulak is most

appropriate. Apparently, it seems that here, as in the cemetery from Cernavodă, there is no major difference in the use of different types of Spondylus adornments in relation to the sex or age of the deceased (Voinea, Neagu and Radu 2009, 17). More elaborate analysis seems to demonstrate that at Durankulak cemetery, in the Hamangia graves, there is proof of preference for certain types of adornments according to sex and age, and even between the two longer periods of the Hamangia culture (I-II and III-IV phases) (Chapman 2003). No matter how interesting these analyses are, they suffer a major shortcoming due to the fact that the Durankulak catalogue of discoveries is contradictory concerning the sex and age of the deceased.

Figure 13. Spatial distribution of the types of adornments in the cemetery area. X = tubular beads, = other types of beads, =

bracelets, ▲ = perforated plates, = pendants, = buttons (Berciu et al. 1961, fig. 1, modified).

The location of the artefacts inside the cemetery The attempt to see if there is any pattern in the spatial distribution of certain types of adornments (Figure 13) led to the following observations: Tubular beads were discovered almost exclusively in the area of the Lower Cemetery and in the collapsed area towards the Danube. They are sporadically present in one of the pits from the northern extremity of the cemetery, and in the Upper Cemetery, but a preference for their use in the graves from the Lower Cemetery is clearly visible. The larger incidence of beads of other shapes in the same western area of the cemetery can be added as an additional argument for the above assertion.

On the other hand, it can be noticed that bracelets occur more often in the Upper Cemetery. An almost exclusive territoriality seems to characterize the pendants that, with one exception, were found in the Upper Cemetery. Perforated plates were found only in the Upper Cemetery. In spite of the fact that for many of the items we do not have a very clear context or sufficient location data, this preferential “zoning” according to the type of adornment seems to be quite clear: Lower Cemetery is characterized by small sized adornments (beads of various shapes), while Upper Cemetery by large sized ones (bracelets, perforated plates, pendants). At the moment we cannot say if this differentiation is due to a chronological difference between the two areas or to a social difference between members of the community

Raluca Kogălniceanu

90

(a differentiation that also involved the use of different area of the cemetery for burial). An interesting piece of research on the size of the Spondylus pieces from the Carpathian Basin dating from the Middle and Late Neolithic of the region led to the following conclusions: 1) during the Middle Neolithic bigger but fewer items were typically used in graves, while during the Late Neolithic a greater number of smaller items was preferred; 2) the quantity of raw material used seems to have remained the same (Siklósi and Csengeri 2011, 47, 53). This chronological difference in the use of different size adornments could constitute a clue to the differences observed at Cernavodă. Of course, more arguments in favour of the chronological factor should be brought forward before any final conclusion can be drawn. Association of adornments with other types of grave goods We tried to analyse the issue of association from two angles: that of the association between different types of adornments and that of association between adornments and other grave goods (Figure 14).

what with what

bead

s

brac

elet

s

perf

orat

ed

plat

es

pend

ants

beads x x bracelets x

perforated plates

pendants x axes xx x x x idols x x

animal bones xxxx x x pottery xx x x xx stone xxx x xx

Figure 14. Association of adornments with other grave goods. From the perspective of the first type of association, we observed that, in most cases, the data seemed to indicate that the association of various types of adornments did not form part of a habitual practice. In the few cases when different types of adornments were found in the same grave, the association was between small pieces associated with large ones. There was no instance of association between two bracelets or between bracelets and pendants or perforated plates. From the perspective of the second type of association, we can say that almost all other types of grave goods were found together with adornments: axes, idols (more rare), pottery, stones and animal bones. This seems to indicate that there are no “preferred” or “banned” associations between types of grave goods. Conclusions At the end of our study we would like to summarize some of the main results of the analysis.

1. The number of adornments made mainly of Spondylus shell and less frequently of other raw materials seems to be much lower than initially expected. 2. Several major types of adornment were identified (beads, bracelets, perforated plates, pendants, buttons and ring) and they correspond largely to those found at Durankulak. 3. The variety of raw materials is more scarce at Cernavodă (predominantly Spondylus, much more rarely marble and occasionally stone, bone and copper) compared to the other known Hamangia cemetery at Durankulak, where the number of artefacts made of stone, bone and copper are much more frequent, together with the use of more types of marine shells. 4. An important aspect noted at Cernavodă was the use of copies or the imitation of certain shapes in a different raw material than that commonly used to produce them, raising questions regarding the affirmation of ethnic identities and of status. 5. Due to the lack of complete information regarding the find locations of a large number of the analysed pieces we could not make meaningful observations regarding the way these adornments were actually used, as body or as clothes’ adornments. 6. The preference of the community to use a certain type of adornment in relation to the sex or age of the deceased could not be definitely asserted for most of the adornment types. It could be due to the scarcity of data or to the fact that no definite preference existed. Nonetheless, we observed that, so far, the pendants seem to have been used exclusively in male graves, while the perforated plates were found exclusively in the female graves, and there seems to have been more beads in the male graves. 7. One of the most important observations made was that regarding the differential distribution of types of adornments inside the cemetery area: smaller ones (different types of beads) mostly in the Lower Cemetery and larger ones (bracelets, perforated plates, pendants) mostly in the Upper Cemetery. It has been noted previously, by the excavators of the cemetery, that there were some visible differences between the two parts of the cemetery, but this is the first time that the difference has been noted for the adornments too. Whether the factors that determined this spatial differentiation were social or chronological remains to be seen. 8. The association of various types of adornments was not a habitual practice. When it existed, the association occurred between small pieces and large ones. 9. We did not address here the issue of fragmentation, as the quantity and quality of data do not support an analysis from this perspective.

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D

91

Acknowledgements We must first give thanks to Oana Damian and Roxana Dobrescu for facilitating our access to the archive and at the Deposits of the Archaeological Institute in Bucharest, and to Dragomir Popovici for the same facilitations at the National Museum of History of Romania in Bucharest. We also thank Petre Roman for allowing us to study the excavation plans and to Alexandru Morintz for digitizing and vectoring the data from the previously mentioned plans. We also need to thank Valentin Radu and Costel Haită for help in determining the raw material of some of the analysed artefacts. This work was possible with the financial support of the Sectorial Operational Program for Human Resources Development 2007-2013, co-financed by the European Social Fund, under the project number POSDRU/89/1.5/S/61104 with the title „Social sciences and humanities in the context of global development -development and implementation of postdoctoral research”. References Beldiman, C., Lazăr, C.A. and Sztancs, D.-M. 2008. Necropola eneolitică de la Sultana – Malu Roşu, com. Mânăstirea, jud. Călăraşi. Piese de podoabă din inventarul M1. Buletinul Muzeului „Teohari Antonescu” XIV/11, 59-72. Berciu, D. 1954. Cernavodă III 1954. Jurnal de şantier, Arhiva Institutului de Arheologie „V. Pârvan” Bucureşti, Fond Berciu, nr. de inventar „C1. Nr. 730 (1120)”, ms. Berciu, D. 1955. Cernavodă II 1955. Jurnal de şantier, Arhiva Institutului de Arheologie „V. Pârvan” Bucureşti, Fond Berciu, nr. de inventar „C5. Nr. 734 (1124)”, ms. Berciu, D. 1960. Deux chefs-d’œuvre de l’art néolithique en Roumanie : le « couple » de la civilisation de Hamangia. Dacia, N.S. IV, 423-441. Berciu, D. 1966. Cultura Hamangia. Noi contribuţii. I. Bucureşti, Editura Academiei RSR. Berciu, D. and Morintz, S. 1957. Şantierul arheologic Cernavoda (reg. Constanţa, r. Medgidia). Materiale şi Cercetări Arheologice III, 83-92. Berciu, D. and Morintz, S. 1959. Săpăturile de la Cernavoda (reg. Constanţa, r. Medgidia). Materiale şi Cercetări Arheologice V, 99-106. Berciu, D., Morintz, S. and Roman, P. 1959. Săpăturile de la Cernavoda (reg. Constanţa, r. Medgidia). Materiale şi Cercetări Arheologice VI, 95-105. Berciu, D., Morintz, S., Ionescu, M. and Roman, P. 1961. Şantierul arheologic Cernavoda. Materiale şi Cercetări Arheologice VII, 49-55.

Chapman, J. 2003. Spondylus bracelets – fragmentation and enchainment in the East Balkan Neolithic and copper Age. Dobroudja 21, 63-87. Comşa, E. 1973. Parures Néolithiques en coquillage marins découvertes en territoire roumain. Dacia, N.S. XVII, 61-76. Comşa, E. 1974. Istoria comunităţilor culturii Boian. Bucureşti, Editura Academiei RSR. Comşa, E. and Cantacuzino, G. 2001. Necropola neolitică de la Cernica. Bucureşti, Editura Academiei Române. Choyke, A.M. 2008. Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic, in P.F. Biehl and Y.Ya. Rassamakin (eds.), Import and Imitation in Archaeology, 5-22. Langenweißbach, Beier & Beran, Schriften des Zentrums für Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte des Schwarzmeerraumes 11. Dimitrijević, V. and Tripković, B. 2006. Spondylus and Glycymeris bracelets: trade reflections at Neolithic Vinča-Belo Brdo. Documenta Praehistorica XXXIII, 237-251. Dimitrov, K. 2002. Archäometallurgische Datenbank. In H. Todorova (ed.), Durankulak, Band II, die prähistorischen gräberfelder von Durankulak, Teil 2, 153-163. Berlin-Sofia, Anubis Ltd. Haşotti, P. 1997. Epoca neolitică în Dobrogea. Constanţa, Muzeul de Istorie Naţională şi Arheologie. Ifantidis, F. and Nikolaidou, M. 2011 (eds.), Spondylus in Prehistory. New data and approaches. Contributions to the archaeology of shell technologies. Oxford, Archaeopress, British Archaeological Reports International Series, 2216. John, J. 2011. Status of Spondylus artifacts within the LBK grave goods, in F. Ifantidis and M. Nikolaidou (eds.), Spondylus in Prehistory. New data and approaches. Contributions to the archaeology of shell technologies, 39-45. Oxford, Archaeopress, British Archaeological Reports International Series, 2216. Kogălniceanu, R. 2009. Hamangia-Anatolia: Differences and Resemblances at the Level of Funerary Practices. In: Arheologia spiritualităţii preistorice în ţinuturile Carpato-ponto-danubiene / Die Archäologie der prähistorischen Spiritualität in dem Karpathen-Pontus-Donau-Raum, 77-88. Constanţa, Editura Arhipescopiei Tomisului. Morintz, S. 1954. Cernavodă I 1954. Jurnal de şantier, Arhiva Institutului de Arheologie „V. Pârvan” Bucureşti, Fond Berciu, nr. de inventar „C2. Nr. 731 (1121)”, ms.

Raluca Kogălniceanu

92

Morintz, S. 1954-1955. Cernavodă II 1954-1955. Jurnal de şantier, Arhiva Institutului de Arheologie „V. Pârvan” Bucureşti, Fond Berciu, nr. de inventar „C3. Nr. 732 (1122)”, ms. Morintz, S. 1955. Cernavodă III 1955. Jurnal de şantier, Arhiva Institutului de Arheologie „V. Pârvan” Bucureşti, Fond Berciu, nr. de inventar „C4. Nr. 733 (1123)”, ms. Morintz, S. 1956. Cernavodă IV 1956. Jurnal de şantier, Arhiva Institutului de Arheologie „V. Pârvan” Bucureşti, Fond Berciu, nr. de inventar „C6. Nr. 745 (1135)”, ms. Morintz, S., Berciu, D. and Diaconu, P. 1955. Şantierul arheologic Cernavoda. Studii şi Cercetări de Istorie Veche VI(1-2), 151-163. Necrasov et al. 1981. (Colectivul Centrului de Cercetări Biologice Iaşi) Studii paleoantropologice care obiectivează continuitatea populaţiilor umane autohtone pe teritoriul patriei noastre şi principalele etape de constituire a poporului român, Contract nr. 134, 1981, ms. Radu, A. 2002. Cultura Sălcuţa în Banat. Reşiţa, Editura Banatica. Schuster, C. 2002. Zu den Spondylus-Funden in Rumänien. Thraco-Dacica XXIII, 37-83. Séfériadès, M.L. 2010. Spondylus and Long-Distance Trade in Prehistoric Europe, in D.W. Anthony and J.Y. Chi (eds.), The Lost World of Old Europe. The Danube Valley, 5000-3500 BC, 179-190. New York, Princeton, Oxford, The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, Princeton University Press.

Siklósi, Z. and Csengeri, P. 2011. Reconsideration of Spondylus usage in the Middle and Late Neolithic of the Carpathian Basin, in F. Ifantidis, and M. Nikolaidou (eds.), Spondylus in Prehistory. New data and approaches. Contributions to the archaeology of shell technologies, 47-62. Oxford, Archaeopress, British Archaeological Reports International Series, 2216. Şerbănescu, D. 1999. The Neolithic necropolis of Popeşti, Vasilaţi commune, Călăraşi County. In M. Neagu (ed.), The Boian civilisation on Romania’s territory, 58-60. Călăraşi, Muzeul Dunării de Jos. Şerbănescu, D. 2002. Observaţii preliminarii asupra necropolei neolitice de la Sultana, jud. Călăraşi. Cultură şi Civilizaţie la Dunărea de Jos XIX, 69-86. Todorova, H. 2002. Durankulak, Band II, Die prähistorischen Gräberfelder von Durankulak. Berlin-Sofia, Anubis Ltd. Tripković, B. 2006. Marine goods in European Prehistory: a new shell in old collection. Analele Banatului S.N. XIV/1, 89-102. Vajsov, I. 2002. Die Idole aus den Gräberfelder von Durankulak. In H. Todorova (ed.), Durankulak, Band II. Die prähistorischen Gräberfelder von Durankulak, Teil I, 257-266. Sofia, Anubis Ltd. Voinea, V. 2010. Un nou simbol Hamangia. Studii de Preistorie 7, 45-59. Voinea, V., Neagu, G. and Radu, V. 2009. Spondylus shell artefacts in Hamangia cultures. Pontica XLII, 9-25. Volschi, V. and Irimia, M. 1968. Descoperiri arheologice la Mangalia şi Limanu aparţinând culturii Hamangia. Pontice I, 45-87.

Appendix The following table contains a synthesis of the data that was considered for this study. The intention is to present the sources available for each artifact that was studied first hand. The table also contains data regarding pieces that we could no longer locate in the deposits, but were published in the years during and immediately after the excavation. Finally, the table contains information about pieces that were only vaguely mentioned in the field notes or are visible on the field drawings, but we could not match them with any other artifact that we had without clear context of discovery. This table is intended to provide raw data that could be of use to other researchers.

The abbreviations used in the table are as follows: - IAB – Institute of Archaeology, Bucharest - MNIR – Museum of National History of Romania - MNA – National Museum of antiquities - C1 – Field notes, book 1: see Berciu 1954 - C2 – Field notes, book 2: see Morintz 1954 - C3 – Field notes, book 3: see Morintz 1954-1955 - C4 – Field notes, book 4: see Morintz 1955 - C5 – Field notes, book 5: see Berciu 1955 - C6 – Field notes, book 6: see Morintz 1956

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D

93

Inve

ntor

y no

. (a

nd in

stitu

tion

whe

re it

em

is lo

cate

d)

Type Location

within cemetery

Drawing of the context

Description in the field

notes

Ant

hrop

olog

ical

de

term

inat

ion

(with

the

anth

ropo

logi

cal

no. f

rom

the

man

uscr

ipt)

Location inside the

grave (source of

information)

Observations

F 1 (IAB) Spondylus tubular beads (8 pcs.) S I, -2.50 m - - -

“near the skull” (on the note attached to the artifact)

F 2 (IAB)

Spondylus tubular beads (6 pcs.)

CVD’62, Col. D, Collapsed area, M B

YES, drawings 1962

- male, mature (404a or b)

near the humeri, at the back of a skeleton apparently crouched on its side (drawing)

marble tubular bead (1 pc.)

F 6 (IAB) marble anthropomorphic pendant (1 pc.)

at the neck (drawing)

F 3 (IAB) Spondylus tubular beads (4 pcs.)

CVD’62, Col. D, Sondage in the collapsed area, M A

YES, drawings 1962

- male, mature (403)

“near the feet” (on the note attached to the artifact)

from a disturbed grave? there are a few separate long bones visible on the drawing in the area of the feet of the main skeleton

- tubular beads (7 pcs.)

CVD’62, Col. D, Sondage in the collapsed area, M C

YES, drawings 1962

- -

six beneath the skull and one at the forehead (drawing)

F 37 (IAB)

Spondylus tubular beads (4 pcs.) ? (Passim) - - - -

F 46 a+b (IAB)

Spondylus tubular beads (21 pcs.)

CVD’56, Col. D, Collapsed area, M a

- - adolescent (290)

found “around the neck” (published report)

- anthropological manuscript mentions only a left parietal for this case (?); - mentioned in Berciu and Morintz 1959, 105.

F 60 (IAB)

Spondylus tubular bead (1 pc.)

CVD’55, south of S IX A, at the surface of the ground

- - - -

F 189 (IAB)

Spondylus tubular beads (2 pcs.)

CVD’55, Col. D, Passim - - - -

- (Spondylus?) tubular bead (1 pc.)

CVD’55, Col. D, S IV g, M 7

YES, drawing area IV

C5 – there is also a drawing of the artifact in the field notes

female?, mature (67)

near the left humerus (drawing)

- (Spondylus?) tubular bead (1 pc.)

CVD’55, Col. D, S IV f, Skull no. 2

drawing area IV – the drawing of the skull exists, but the bead does not figure on it

C5 – there is also a drawing of the artifact in the field notes

- near the skull (field notes)

found during the lifting of the human remains

MNIR 11.669-11.673 (MNA V 6713)

Spondylus tubular beads (5 pcs.) CVD, … ? - - - -

published in Berciu 1966, fig. 38/2

- shell tubular bead (1 pc.)

CVD’55, Col. D, S IV e, M 16/Complex g

YES, drawing area IV C4

female, 50-60 years (72)

near the right forearm (drawing + field notes)

Raluca Kogălniceanu

94

Inve

ntor

y no

. (a

nd in

stitu

tion

whe

re it

em

is lo

cate

d)

Type Location

within cemetery

Drawing of the context

Description in the field

notes

Ant

hrop

olog

ical

de

term

inat

ion

(with

the

anth

ropo

logi

cal

no. f

rom

the

man

uscr

ipt)

Location inside the

grave (source of

information)

Observations

- tubular bead (1 pc.) CVD'54, Collapsed area - C1 -

stuck to the inside of a skull fragment (field notes)

- tubular beads (2 pcs.) CVD'54, S IV A - cassette, M 1

drawing area IV – just the contour of the pit

C2 male, 60 years (42a)

beneath the right ear (field notes)

- shell square bead (1 pc.)

in the neck area (field notes)

turned to dust on removal from ground

MNIR 11.674 (MNA ?)

Spondylus tubular bead (1 pc.)

CVD, … ? - - - - published in Berciu 1966, fig. 38/1

Spondylus biconvex beads (3 pcs.) Spondylus cylindrical beads (7 pcs.)

- cylindrical bead (1 pc.)

CVD'54, S IV, M 7 - C2 male, 40 years

(57) at the neck (field notes)

- shell beads (2 pcs.) (cylindrical and biconvex ?)

CVD’56, Col. D, S D, □ 1 l (m), M 33

drawing area D – the drawing of the grave exists, but the beads do not figure on it

C6 - near the left humerus (field notes)

the field notes say: “one of cylindrical shape, another one like a barrel and another one in the shape of a miniature vessel”

-

„shell pearl”

CVD’55, Col. D, S IV j, M 1

YES, drawing area IV

-

- -

in association with 2-3 human bones (humerus) and an axe

round copper bead (1 pc.) C5

-“round bead” on the drawing - the copper bead mentioned in Berciu and Morintz, 1957, 87

F 36 (IAB)

Spondylus trilobite beads (3 pcs.) ? (Passim) - - - -

F 38 (IAB)

Spondylus cylindrical bead (1 pc.)

? (Passim) - - - -

F 41 (IAB)

Spondylus bracelet (2 fragments)

CVD’56, Col. D, S D2, M 36

drawing area D – the drawing of the grave exists, but the beads do not figure on it

C6 male, mature (186+225B)

on the belly (field notes)

-

shell „barrel-type” beads (8 pcs.) (probably biconvex)

at the neck (field notes)

F 84 (IAB)

Spondylus bracelet (1 pc.)

CVD’55, Col. D, Ş IX A, □ 6, -0.50 -0.55 m

-

C3 C5 – there is also a drawing of the artifact in the field notes

- - isolated? (field notes)

- shell bracelet (fragment or fragments)

CVD’56, Col. D, S D, □ 2j, -0.51 m

YES, drawing area D C6 - -

found in association with pottery fragments from a large vessel and a fragmentary human bone

Adornments from the Hamangia cemetery excavated at Cernavodă – Columbia D

95

Inve

ntor

y no

. (a

nd in

stitu

tion

whe

re it

em

is lo

cate

d)

Type Location

within cemetery

Drawing of the context

Description in the field

notes

Ant

hrop

olog

ical

de

term

inat

ion

(with

the

anth

ropo

logi

cal

no. f

rom

the

man

uscr

ipt)

Location inside the

grave (source of

information)

Observations

- shell bracelet (1 fragment)

CVD’56, Col. D, Ş R2, □ 3, -1.20 m

YES, drawing area R - female, mature

(111 ?) -

found close to M1, but at quite a large difference in depth (M1 was found at -0.80 -0.90 m)

- shell bracelet (1 fragment)

CVD’54, Col. D, Ş IA, □ 11, -1.00 m

- C2 - -

found in the archaeological layer; the location corresponds to Pit no. 1

MNIR 11.666 (MNA V 6715)

marble bracelet (1 pc.) CVD’56, Col. D - - -

published in Berciu 1966, fig. 38/5

F 340 (IAB)

- Spondylus perforated plate (1 pc.)

CVD’56, Col. D, S D1, □ 5a, -0.70 m

YES, drawing area D C6 - -

on the drawing is labeled “bracelet-pendant”; in association with sherds, 2 small axes and one bone fragment

- shell perforated plate (1 pc.)

CVD’56, Col. D, S D, □ 1g

YES, drawing area D - - - somehow isolated

of any other finds

- perforated plate (1 pc.)

CVD’56, Col. D, S D, □ 3e, -0.28 m

YES, drawing area D C6 female, adult

(200+201) -

in association with disturbed human remains M? (M 68)

F 14 (IAB) stone button (1 pc.) ? (Passim) - - - -

F 117 (IAB)

Spondylus button (1 pc.)

CVD’56, Col. D, S D1, -0.25 m

- - - -

F 26 (IAB)

Spondylus arched pendant (1 pc.)

CVD’58, Col. D, Ş X E - - - - imitates an

animal fang

- pendant (1 pc.) CVD’55, Col. D, Ş IX D, □ 4-6, M 11

YES, drawing area IX -

male, 55-60 years (90)

- the raw material is not specified

- shell pendant (1 pc.) CVD’56, Col. D, S D, □ 3a, -0.11 m

YES, drawing area D C6 male, 30 years

(156+157+167 ?) - in the vicinity of M3

MNIR 11.668 (MNA V 6717)

marble rounded cruciform pendant (1 pc.)

CVD'56, Col. D - - -

published in Berciu and Morintz 1959, 103.

- marble anthropomorphic pendant (1 pc.)

CVD, Col. D - - - -

published in Berciu 1960, fig. 9/1 and Berciu 1966, fig. 38/4.

F 39 (IAB) bone ring (1 pc.) ? (Passim) - - - -

![]a geneza culturii Hamangia, cel puOn la dezvoltarea ei · cultura Hamangia, şi pe de altă parte în ce măsură putem sau nu accepta o prezenţă etnică 'fi precucutenienilor](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/5e036f2726d48d523211b9c6/a-geneza-culturii-hamangia-cel-puon-la-dezvoltarea-ei-cultura-hamangia-i-pe.jpg)