KENZO TANGE: THE ARCHITECT OF POSTWAR JAPANESE … · 2017. 5. 12. · Kenzo Tange’s...

Transcript of KENZO TANGE: THE ARCHITECT OF POSTWAR JAPANESE … · 2017. 5. 12. · Kenzo Tange’s...

1 | P a g e

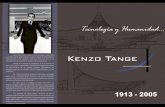

KENZO TANGE:

THE ARCHITECT OF POSTWAR JAPANESE MODERNISM

CONNOR PETER ROBSON – 16007119

KA4025 – 2016/17

2 | P a g e

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 3

INTRODUCTION 4

1 DEVELOPMENT AND EXPERIMENTATION

(1946-1958) 5

2 URBAN PLANNING, METABOLISM AND POST-ECONOMIC MIRACLE

(1958-1996) 8

CONCLUSION 12

APPENDIX 13

REFERENCES 15

BIBLIOGRAPHY 17

3 | P a g e

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS (WITH CREDITS)

CHAPTER 1

Figure 1.1 Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. “Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, an

unforgettable place in my life”. explorejapan.jp. ExploreJapan. n.d. Web. 8

May 2017, 11:10.

Figure 1.2 Robson, Connor. “Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park Cenotaph”. 2016. PNG

file.

CHAPTER 2

Figure 2.1 Robson, Connor. “Conceptual Diagram of Kenzo Tange’s 1960 Tokyo Plan”.

2017. PNG file.

Figure 2.2 The Yoyogi National Gymnasium complex. “Olympic construction transformed

Tokyo”. japantimes.co.jp. The Japan Times. 10 Oct 2014. Web. 8 May 2017,

11:19.

Figure 2.3 Tepper, Natalie. Fuji-Sankei Communications Group Headquarters Building.

n.d. Architectural Excellence: 500 Iconic Buildings. By Paul Cattermole.

Compendium Publishing Limited, London, 2008. Print.

APPENDIX

Figure 3.1 Robson, Connor. “Keio University Shonan Fujisawa Campus Courtyard”.

2016. PNG file.

4 | P a g e

INTRODUCTION

Kenzo Tange (1913-2005), a Japanese-born architect, is credited with being one of the key

practitioners of the Modernist movement within Japan, adapting 1930s euro-modernist theory

to the cultural concerns and issues of a devastated, post-war Japan. The country’s

requirements during this period placed Tange in a key position due to his interest in urban

planning and redevelopment.

Through involvement with the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), the

1960 World Design Conference and 1970 World Exposition, Tange played a major role in

both bringing western development to Japan and establishing a post-war Japanese style

within the world architectural community. Both were progressed by the next generation of

Japanese architects, many of whom Tange had taught or influenced, including the pioneers of

the Metabolist movement, impacting the development and attitudes of modern Japanese

architecture.

5 | P a g e

CHAPTER 1:

DEVELOPMENT AND EXPERIMENTATION

(1946 – 1958)

Kenzo Tange began his career under the modernist architect, Kunio Maekawa, building up

his reputation through competitions. During this formative period, he became a part of the

international debate within the CIAM, with particular interest in the 1933 ‘functional city’

debate. His early designs were heavily inspired by Le Corbusier, but most of his work prior to

1949 was never built.

Tange’s international acclaim began when he won the 1946 competition to design a memorial

museum at ground zero in Hiroshima, with the architect later being commissioned to design

the surrounding park also. Both Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (Figure 1.1) and its

surrounding park illustrate the key goals of Tange’s architectural work: the introduction of

international developments into Japanese architecture and the continuation of the 1930s’

growth and prosperity.

Figure 1.1

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

6 | P a g e

The modernist components of the design are immediately apparent, with the slight pilotis,

created using reinforced concrete,1 allowing free mass movement under the building. The

significance of the building helped popularize concrete construction within Japan, which

would have been impossible without introducing western advances in engineering due to the

country’s previous reliance on timber.2 However, Japanese tradition was not fully omitted,

seen in the building being elevated and the horizontality of the space’s layout. The best

example of his initial goals, however, was the western engineered form of the cenotaph

(Figure 1.2) which mimics the roofs of ancient Japanese haniwa, previously used to mark

mass tombs during the war-torn Kofun period (c. 250 to c. 600 CE). 3

Figure 2.2

Hiroshima Peace Memorial

Park Cenotaph

7 | P a g e

This stage of Tange’s career is usually referred to as his first phase, a time when his ideas and

aspirations were limited or not entirely realised, instead relying on Japanese tradition and Le

Corbusier’s inspiration. For example, Tange used the recessed windows of the Unité

d’Habitation, along with courtyards and veranda-like balconies, indicative of shrine and

palace architecture. Tange was heavily criticized for his reliance on tradition, with his

attempts to replicate Japanese timber construction with steel and concrete unwarranted.

In response to the criticism and to further his own goals, Tange undertook a large number of

projects, primarily local government buildings, between 1955 and 1958. This second phase

was focused on developing a less traditional language and experimented with new concepts,

including the combination of both Western and Japanese styles into a single residence, which

is in heavy demand today.4 A significant example is the town hall of Imabari, where he

experimented with raw concrete facades, using light to emphasize the striking material

qualities of the projecting walls, developed in previous designs, resembling Italian architect

Pier Luigi Nervi’s work.5

1958 saw his third phase, a more mature style, focusing more on utilizing space than its

context. He continued to develop his Brutalist concrete structuring alongside other concepts,

diverging from euro-modernism and Le Corbusier’s school of thought. He even challenged

the Swiss’ solution for merging residential and commercial areas together within mass

housing units, preferring a more organic arrangement of space; 6 an idea which was further

debated as part of the Metabolists’ founding principles.

8 | P a g e

CHAPTER 2:

URBAN PLANNING, METABOLISM AND POST-ECONOMIC MIRACLE

(1958-1996)

The 1960s was a period of growth and change within Japan, with Tange able to explore his

utopian ideas for urban regeneration alongside architects of similar disposition. After vast

amounts of experimentation and theoretical work, Tange and the group’s work culminated at

the 1970 World Exhibition in Osaka, before parting ways. Tange continued to practice

Modernist and Metabolist architecture until his death in 2005.

With his premier foray into urban planning, Tange produced the Tokyo Plan 1960: a first

attempt to reorganise a metropolis, 10 million inhabitants strong. The design had been

developing throughout his previous works, many of which fit into it, with Tange proposing

Figure 2.1

Conceptual Diagram of Kenzo

Tange’s 1960 Tokyo Plan

9 | P a g e

the conversion from radial plan to a central axis, expanding into the underdeveloped bay,

functioning much like the corridors in residential architecture imported to Japan in the 19th

century.1 The city would be organised using the ‘open building’ approach on a large scale,

allowing the city to develop itself without the need for complete renewal. It is also apparent

that Tange’s references to tradition were becoming more conceptual, with the concept of

‘impermanence’ being rethought and repurposed to a modern era. Tange’s plan also bared

resemblance to Le Corbusier’s Paris Voisin (1925), but elected to connect key

megastructures via elevated pathways, opposed to the individualistic isolation of the Swiss’

proposal.

By the World Design Conference 1960 in Tokyo, Tange had long been part of the

international community, unlike other Japanese architects, placing him uniquely to help

define Japan’s place within it. The conference saw Tange introduce several of Japan’s current

most famous designers, some of whom he’d taught. The most famous of his students were

those who formed the Metabolists, based on Tange’s utopian principals of creating organic

cities able to transform with the times.2 They would debate the fundamental requirements of

Japanese architecture, including the development of a unique national identity and the

appropriation of the western megastructure typology. Selling their manifesto, Metabolism

1960: Proposals for a New Urbanism, at the event, Tange himself had no work published

within it. His later work, however, very much reflected the theories of the group, in the

development of a true international style, devoid of history and site context.3

The architecture of the Olympic Stadiums (Figure 2.2), highly praised for their atypical

structuralism, were primary examples of Tange’s own Metabolist designs. The mechanistic

dynamic layout and engineering of reinforced concrete walls bore influence from Eero

Saarinen’s curvilinear architectural language, adapted for a Metabolist style, whilst also

appearing similar to older temple architecture. The occasion of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics

allowed Tange’s bid to establish a Japanese architectural language, having readjusted western

architectural techniques and technology, such as the suspension of the roofs by cable, for the

world stage, laying the foundations upon which his students would build. Also addressing

concerns of maximum utilization of used land via multipurpose space,4 the stadiums were set

along a North-South axis to conform to Tange’s own 1960 Tokyo Plan, which itself was

partially realised in the 1965 regeneration of Skopje, Macedonia.

10 | P a g e

The Metabolists created primarily theoretical concepts until their climax in the form of the

1970 World Exposition, master planned by Tange, who invited them to design a number of

the pavilions used for the event.. Tange himself designed a highly organic layout,

highlighting Osaka’s topography, using a central axis to efficiently organize communications.

The Theme Space’s 3 level plan, parodying that of Tange’s Tokyo Plan, showed off the

spatial organization, but further exploration was limited, and the World Exposition is

considered to be the end of Metabolists as a group, with members taking different approaches

to developing the theory. The event also seemed to bring to an end the movement’s influence,

as the Metabolist designs were largely passed over by mainstream media, who were more

interested in the promotion of Japan’s advancing technology,5 although Team 10, as well as

British group, Archigram, were notably persuaded by the concepts and theories on show.

After this, Tange took on international projects, never faltering from Metabolism, rejecting

Post-Modernism.6 For instance, his urban planning pursuits saw him propose a lateral axis

through Paris in 1985. However, Tange continued to take commissions within Japan from

various sources. The Fuji-Sankei Communications Group Headquarters Building (Figure

Figure 2.2

The Yoyogi National

Gymnasium complex

11 | P a g e

2.3), completed in 1996, intrinsically linked three buildings, organising them organically

around the required communications, leaving voids in space to suggest the possibility of

future growth,7 showing he was never strayed far from Metabolist theory.

Figure 2.3

Fuji-Sankei Communications

Group Headquarters Building

12 | P a g e

CONCLUSION

Kenzo Tange’s architectural legacy can be measured by how well he fulfilled his goals and

the influence he had on the development of Japanese architecture. On one hand, his works

and urban planning were unable to emulate the urban and cultural growth of 1930s. On the

other hand, his buildings, many of which have since become iconic landmarks, have

undoubtedly been influential, succeeding in adapting international developments. The next

generation were thoroughly invested in the merits of its application both within Japan and

internationally, effectively modernising Japanese architecture through Tange’s metabolic

cycle of constant development and innovation. He has found solutions to various post-war

issues, many of which Japanese architects still debate, including the usage of multifunctional,

open space and reducing the amount wasted.7 His role in moving away from traditional

architecture can also be felt in the modern Japanese disregard for set style, shape or size.8

Finally, Tange’s influence on Japanese architecture can be felt through the architects he

inspired, who have derived their own styles, and continue to enhance and bring Japan to the

forefront of architectural consciousness.

13 | P a g e

APPENDIX

In addition to the content already discussed, it is worth briefly reviewing a few of the

architectural careers Tange has influenced. For this, I have decided to focus on two of the

more famous examples, whose works have been recognised internationally in the form of the

Pritzker Prize: Fumihiko Maki (1993 Laurette) and Tadao Ando (1995 Laurette).

Fumihiko Maki, one of Tange’s University of Tokyo students, embraced a fairly similar

worldview to that of Tange, as can be seen in the similarities between their buildings, such as

the use of raw concrete walls and courtyards. One of the more notable aspects of his career is

his exploration of the unification of western and Japanese architecture: a concept which is in

high demand currently and one that Tange had also tackled.

Figure 3.1

Keio University Shonan

Fujisawa Campus Courtyard

14 | P a g e

Unlike Maki, Tadao Ando did not study directly under Kenzo Tange, although, in interviews,

it is evident that Ando harbours a great deal of respect for Tange. Ando’s works, much like

that of Tange and Maki, often bare large concrete facades, with Ando’s mastery of using

natural light allowing him to manipulate and express the materiality of his structures, in a

similar way as Tange did with the projecting walls of the town hall in Imabari.

We see in both examples similarities between the younger generation and Tange, showing

that Tange’s works were very much forerunners of modern Japanese architecture.

I also strongly believe it is worth noting recent events, in the case of the 2020 Summer

Olympics, set to be held in Tokyo. Tange’s influence can be seen in the organisation of the

planned construction and its parallels with the 1960 Tokyo Plan. Tange’s design for mass

residential areas are comparable with the plans for the Olympic Village, and have even been

located close to the harbour, an area which Tange believed needed regeneration and

reclamation from the defunct factories it bore through the mid-20th century (as can be seen in

Figure 2.1). Alternatively, and perhaps controversially, Tokyo had planned to retrofit

Tange’s existing Olympic Stadiums from 1964, with Zaha Hadid Architects poised to be the

designers. However, as of July 2015, the UK-based architectural practice were removed from

their position amid protest from various Japanese architects, including Fumihiko Maki, over

the concept of changing Tange’s design: a testament to the respect that Tange and his

Olympic Stadiums have gained.

15 | P a g e

REFERENCES

CHAPTER 1

1 Seo, Kyung Wook. “Asian Architecture and Open Building”. An Introduction to

Architectural History and Theory. Northumbria University. Lipman Building,

Newcastle-upon-Tyne. 23 Feb 2017. Lecture.

2 Ishimoto, Yasuhiro and Kenzo Tange. Katsura: Tradition and Creation in Japanese

Architecture Redesigned Edition. Yale University Press Ltd., London, 1972. p. 24.

3 Shirai, Yoko Hsueh. “Haniwa Warrior (Article)”. Khanacademy.org. Khana

Academy. n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2017, 13:32

4 Kultermann, Udo and Kenzo Tange. Kenzo Tange: 1946-1969: Architecture and

Urban Design. Pall Mall Press, London, 1970. p. 88.

5 Ibid. p. 78

6 Ibid. p. 106.

CHAPTER 2

1 Seo, Kyung Wook. “Asian Architecture and Open Building”. An Introduction to

Architectural History and Theory. Northumbria University. Lipman Building,

Newcastle-upon-Tyne. 23 Feb 2017. Lecture.

2 Denison, Edward. 30 Second Architecture. Ivy Press, London, 2013. p. 114.

3 Goldhagen, Sarah Williams and Réjean Legault. Anxious Modernisms:

Experimentation in Postwar Architecture Culture. Canadian Centre for Architecture,

Montréal, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, 2000. p. 280.

16 | P a g e

4 Fazio, Michael, Marian Moffett and Lawrence Wodehouse. A World History of

Architecture Third Edition. Laurence King Publishing, London, 2013. p. 515.

5 Denison, Edward. 30 Second Architecture. Ivy Press, London, 2013. p. 114.

6 “Kenzo Tange”. architectuul.com. Architectuul. n.d. Web. 25 April 2017, 14:13

7 Cattermole, Paul. Architectural Excellence: 500 Iconic Buildings. Compendium

Publishing Ltd., London, 2008. p. 436

CONCLUSION

1 Pollock, Naomi. Jutaku: Japanese Houses. Phaidon Press Ltd., London, 2015. p. 11.

2 Ibid. p. 6.

17 | P a g e

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Fumihiko Maki: 1993 Laureate”. pritzkerprize.com. The Pritzker Architecture Prize. n.d.

Web. 7 May 2017, 20:32.

“Kenzo Tange”. architectuul.com. Architectuul. n.d. Web. 25 Apr 2017 14:13.

“Kenzo Tange”. praemiumimperiale.org. Praemium Imperiale. n.d. Web. 26 Apr 2017 15:53.

“Kenzo Tange: 1987 Laureate”. pritzkerprize.com. The Pritzker Architecture Prize. n.d. Web.

24 Apr 2017, 17:51.

“Kenzo Tange Facts”. yourdictionary.com. Your Dictionary. n.d. Web. 5 May 2017, 20:26.

“Kenzo Tange Japanese Architect”. britannica.com. Encyclopaedia Britannica. n.d. Web. 26

Apr 2017 15:21.

“Kurashiki City Hall”. greatbuildings.com. The Architecture Week. n.d. Web. 5 May 2017,

20:03

“Paris Voisin, Paris, France, 1925”. Fondationlecorbusier.fr. Fondation Le Corbusier. n.d.

Web. 25 Apr 2017 17:53.

“St Mary’s Cathedral”. Tokyo.catholic.jp. Archdiocese of Tokyo. n.d. Web. 25 Apr 2017

12:43

“Tadao Ando: 1995 Laureate”. pritzkerprize.com. The Pritzker Architecture Prize. n.d. Web.

7 May 2017, 21:01.

“The Osaka World Exhibition 1970”. site.expo2000.de. The History of World Exhibitions.

n.d. 24 Apr 2017, 14:51

Campbell-Dollaghan, Kelsey. “Tokyo’s Clever Plan to Reuse 1964 Olympic Stadiums for the

2020 Games”. gizmodo.com. Gizmodo. 9 Sept 2013. Web. 6 May 2017, 22:29.

18 | P a g e

Cattermole, Paul. Architectural Excellence: 500 Iconic Buildings. Compendium Publishing

Ltd., London, 2008.

Chong, Doryun. Tokyo: 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde. The Museum of Modern Art, New

York, 2012

Cooper, Graham. Project Japan: Architecture and Art Media Edo to Now. The Images

Publishing Group Pty Ltd, Victoria, 2009.

Crouch, Christopher. Modernism in art, design and architecture. Macmillan Press Ltd.,

London, 1999.

Denison, Edward. 30 Second Architecture. Ivy Press, London, 2013.

Fazio, Michael, Marian Moffett and Lawrence Wodehouse. A World History of Architecture

Third Edition. Laurence King Publishing, London, 2013.

Goldhagen, Sarah Williams and Réjean Legault. Anxious Modernisms: Experimentation in

Postwar Architecture Culture. Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal, Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, Cambridge, 2000.

Howarth, Dan. “Japan scraps Zaha Hadid’s Tokyo 2020 Olympic Stadium”. dezeen.com.

Dezeen. 17 July 2015. Web. 7 May 2017, 21:27.

Ishimoto, Yasuhiro and Kenzo Tange. Katsura: Tradition and Creation in Japanese

Architecture Redesigned Edition. Yale University Press Ltd., London, 1972.

Kehl, James. “Metabolism and the Unit”. jkehl.com. n.p. n.d. Web. 25 Apr 2017, 11:53.

Kultermann, Udo and Kenzo Tange. Kenzo Tange: 1946-1969: Architecture and Urban

Design. Pall Mall Press, London, 1970.

19 | P a g e

Meech, Julia. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art of Japan: The Architect’s Other Passion. Harry

N Abrams Incorporated, New York, 2001.

Nakamori, Yasafumi. Katsura Picturing Modernism in Japanese Architecture Photographs by

Ishimoto Yasuhiro. Museum Of Fine Arts, Houston, 2010.

Pollock, Naomi. Jutaku: Japanese Houses. Phaidon Press Ltd., London, 2015.

Roberts, Nate. “Communist Architecture of Skopje, Macedonia – A Brutal, Modern, Cosmic,

Era”. yomadic.com. Yomadic, 6 May 2013. Web. 26 Apr 2017 14:44.

Seo, Kyung Wook. “Asian Architecture and Open Building”. An Introduction to

Architectural History and Theory. Northumbria University. Lipman Building, Newcastle-

upon-Tyne. 23 Feb 2017. Lecture.

Schalke, Meike. “The Architecture of Metabolist. Inventing a Culture of Resilience”.

mdpi.com. Multidisciplinary Publishing Institute, 13 June 2014. Web. 25 Apr 2017, 12:04.

Schittich, Christain. In Detail: Japan: Architecture, Constructions, Ambiances. Birkhäuser,

Basel, 2002.

Shirai, Yoko Hsueh. “Haniwa Warrior (Article)”. khanacademy.org. Khana Academy. n.d.

Web. 24 Apr. 2017, 13:32

Slessor, Catherine. “The Unrealised Vision for Japan’s Future”. architectural-review.com.

The Architectural Review, 31 October 2011. Web. 25 Apr 2017, 12:07.

Watkin, David. A History of Western Architecture 4th Edition. Laurence King Publishing,

London, 2005.