Jamieson 2005 Colonialism, Social Archaeology and Lo Andino. Historical Archaeology in the Andes

-

Upload

pomeenriquez -

Category

Documents

-

view

16 -

download

0

Transcript of Jamieson 2005 Colonialism, Social Archaeology and Lo Andino. Historical Archaeology in the Andes

-

This article was downloaded by:[University College London]On: 8 November 2007Access Details: [subscription number 731858869]Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

World ArchaeologyPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713699333

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino:historical archaeology in the AndesRoss W. Jamieson aa Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia

Online Publication Date: 01 September 2005To cite this Article: Jamieson, Ross W. (2005) 'Colonialism, social archaeology andlo Andino: historical archaeology in the Andes', World Archaeology, 37:3, 352 - 372To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/00438240500168384URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00438240500168384

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expresslyforbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will becomplete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should beindependently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with orarising out of the use of this material.

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Colonialism, social archaeology andlo Andino: historical archaeology inthe Andes

Ross W. Jamieson

Abstract

The rich prehistoric archaeological record in Andean South America has obscured the importance ofpost-conquest historic sites in the region. Archaeologists researching the former Spanish colonieshave long turned to the US Borderlands and the Caribbean for models dening the archaeology of

Spanish colonialism. Recently, however, Andean archaeologists have begun to create new emphaseson the archaeology of colonialism and archaeologies of the later Andean republics. This region was acore area of Spanish overseas expansion in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with much of the

precious metal wealth of the empire produced in Andean mines. Today archaeologists in the Andeanrepublics of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina, and the foreignresearchers who also work in the region, are overcoming geographic, nancial and linguistic barriers

to create a unied Andean historical archaeology.

Keywords

Andes; South America; historical archaeology; colonialism; Spanish.

The Andes

Scholars have classied the Andean region as unique in its prehistory and culture, with its

stunning geographical contrasts and human adaptations to distinct elevations and

environmental challenges. The geographic limits of the Inka Empire have dened a

particular research zone for prehistorians and anthropologists that has unied Andeanists

into a strongly interactive group of researchers around the globe (Isbell and Silverman

2002; Salman and Zoomers 2003). Historians of the colonial period have also found the

Andes a convenient geographical and administrative region to build contacts around,

creating an Andean colonial history focused on the similarities and contrasts between

World Archaeology Vol. 37(3): 352372 Historical Archaeology

2005 Taylor & Francis ISSN 0043-8243 print/1470-1375 onlineDOI: 10.1080/00438240500168384

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Spanish colonialism in the Andes and that of other regions of the globe (Andrien 2001;

Larson and Harris 1995).

Much of this work is organized around the principle that Andean culture is somehow

unique, united in something often referred to as lo Andino, a catchphrase for things

culturally Andean. These include the concepts of ecological complementarity (Masuda

et al. 1985), apocalyptic visions of Andean cultural history (Allen 1988), the

organization of villages into moiety divisions, bilateral kinship and reciprocity networks

(Skar 1982) and the personication of mountains as deities with familial relationships

(Bastien 1978). These and other concepts, packaged into the broad concept of lo Andino,

create a picture of highland Andean peasants as unsullied bearers of cultural practices

continued from pre-Hispanic times. Such a perspective can help researchers recognize,

and focus on, the continuities in Andean culture, and yet it also implies an essentialism

and timelessness that removes Andean peoples from the ow of history (Starn 1991;

Weismantel 1991).

It is interesting, therefore, that archaeologists of the Spanish colonies have not yet

created any sort of uniquely Andean brand of historical archaeology. Part of this may be

due to the heavy investment in idealizing the pre-Columbian past as a model for national

identity (Acuto and Zarankin 1999: 8; Guthertz Lizarraga 1999). The enormous impact of

Spanish colonialism on Andean cultural practices can be seen to be minimized both by

scholars intent on showing Andean cultural continuity and by those intent on celebrating

nationalism in the Andean republics. The practice of historical archaeology in the Andes is

on the rise, however, and is coming into its own as an area of interest to historical

archaeologists globally.

This practice has not been accompanied by any unity of theoretical approaches. A

tradition of social archaeology, applying Marxist social thought to archaeological

questions, has been explicitly present in Peru and Venezuela since the beginning of the

1970s (Patterson 1994), and has also had inuence in Ecuador (Benavides 2001).

Taking as its roots the work of Luis Lumbreras in Peru (1974) and Mario Sanoja and

Iraida Vargas in Venezuela (1978), social archaeology was dened by its dialectical

method, focus on modes of production and other concerns closely related to Marxist

social science. Sanoja and Vargas have been particularly important voices, as they were

pioneers both in social archaeology and in historical archaeology in Venezuela. Social

archaeology as a paradigm has held great appeal for some Andean historical

archaeologists, particularly when a major focus of their work is on the exploitation

of subaltern peoples during Spanish colonization (Sanoja Obediente and Vargas Arenas

2002; Funari and Zarankin 2003). Marxist social theory goes well beyond ivory tower

debate in the Andes, where socialist and communist political movements are

intertwined in complex ways with indigenous identities and realities, and where

political and racial debate has resulted in violent, and ongoing, confrontations as well

as creative accommodations (Colloredo-Mansfeld 1998; Gorriti Ellenbogen 1999;

Trawick 2003). Andean social upheaval is accompanied by debate in the current

archaeological literature, where advocates of Latin American social archaeology

(Benavides 2001; Fournier Garcia 1999; Patterson 1994; Vargas Arenas and Sanoja

Obediente 1993) are vehemently opposed by many other archaeologists (Oyuela-

Caycedo et al. 1997; Politis 2003; Valdez 2004). The boundary between politics and

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 353

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

archaeology in the Andes is permeable, to the point that in some South American

countries social archaeology was actively quashed by military governments in the 1970s

and 1980s (Politis 1995).

The majority of historical archaeologists in the region are, however, not actively

involved in this debate. Many could be classied as cultural historians, or as nationalist

archaeologists, seeking to commemorate the colonial past, often through projects whose

main goal is the restoration of colonial buildings as monuments. Other approaches to the

past have also recently gained inuence, particularly post-processual, or contextual,

approaches, with invocations of Foucault (Gomez Romero 2002), hybridity (Therrien

2002a) and theories of consumption (Therrien et al. 2002: 12) appearing with some

regularity in recent work.

A healthy diversity of theoretical approaches has thus emerged in Andean historical

archaeology in the last ten years. This diversity is strongest in the Southern Cone. A series

of regional conferences, many of them focused on the ties between Brazilian, Uruguayan

and Argentinean researchers (Funari 1996), have recently brought historical archaeolo-

gists working in various regions of South America together in Argentina (Santa Fe, 1995;

Mendoza, 2000; Tierra del Fuego, 2003), Chile (Santiago, 2001; Americanists Conference

Santiago, 2003) and Panama (2001). Conferences such as these have allowed a range of

researchers who have formed a new focus on the historical archaeology of South America

to exchange ideas, and, in at least the Mendoza case, the conference results have been

published (Congreso Nacional de Arqueologa Historica 2002). This is an excellent start to

creating international interchange on the many issues that historical archaeologists

working in the Andean nations hold in common.

The beginnings

In the Andes historical archaeology is a subject that has emerged as a coordinated research

eort only over the last twenty years, although its origins run back to the early part of the

twentieth century. It was in the mid to late 1960s that colonial archaeological remains

began to be treated more seriously, whether in Venezuela (Sanoja Obediente 1968), Peru

(Cardenas Martn 1970; Arrieta Alvarez 1975) or Chile (Berdichewsky Scher and Calvo de

Guzman 1972). From the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s we see a twenty-year period in which

eorts were made to develop various research projects, although these suered from the

isolation of the researchers from academic interchange and from the fact that many of

these studies continued to be undertaken only because of chance nds of colonial remains

during prehistoric projects (Beck et al. 1983; Munizaga et al. 1975; Sanhueza Tapia and

Olmos Figueroa 1981).

Truly pioneering eorts were made, however, in two particular cases. Mario Sanoja

(1978) expanded his work in Venezuela, undertaking the excavation of a seventeenth-

century Spanish fortress in the Orinoco region, and Omar Ortiz-Troncoso (1976)

excavated a sixteenth-century Spanish harbour in the Straits of Magellan. Neither of these

projects was geographically Andean, but both represent early eorts to design and

implement archaeological research on historic sites in the Andean countries, beyond

chance nds related to prehistoric excavations.

354 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

It is in the 1980s that historical archaeology really got its start in the Andean countries.

In Argentina the beginnings of the professionalization of historical archaeology date to the

period immediately following the end of military rule in 1984, when Argentinean

archaeologists were able to begin working in relative freedom on historic projects (Funari

1997: 194). One of the most important gures in Argentinean historical archaeology has

been Daniel Schavelzon, whose work on the urban archaeology of Buenos Aires

introduced many other Argentine researchers to a globally informed methodology in the

archaeology of both colonial and republican period sites in the Rio de la Plata (Schavelzon

1992, 1998, 2000a). In Peru, an important early project was the 1985 to 1990 Moquegua

Valley Project (Fig. 1), run by Prudence Rice (1995, 1996). This was an eort which started

the careers of several US scholars in the area, including Greg Smith (1997), Susan

DeFrance (1996, 2003) and Mary Van Buren (1996, 1999). Finally, two extensive urban

studies have been key ongoing, large-scale projects that have moved urban archaeology in

the Andes forward immensely. These are Iraida Vargas Arenas and Mario Sanojas years

of research in urban Caracas, Venezuela, beginning in 1986 (Sanoja Obediente and Vargas

Arenas 2002), and J. Roberto Barcena and Daniel Schavelzons extensive work in

Mendoza, Argentina, which began in earnest in 1989 (Barcena 1993; Schavelzon 1998).

Both ongoing projects are funded by their respective municipalities and government

cultural agencies, and both have produced extensive published results on various urban

archaeological issues. The focus has been on mitigation work when urban renewal schemes

are proposed and integrating archaeology into the commemorative aspects of municipal

urban renewal. Although, in both cases, sites are not chosen nor goals created based on

purely research questions, both projects take advantage of Andean urban realities to

conduct exemplary salvage and restoration archaeology of important sites in historic

urban cores. The fact that the results of these projects have been extensively published,

rather than languishing as reports to government agencies, is particularly encouraging.

Continuity in mortuary practices

The earliest historical archaeology in the Andes is that of contact-period cemeteries.

Baltasar Jaime Martnez Companon, Bishop of Trujillo, Peru, can be credited with

undertaking the rst historical archaeology in the region, in the 1780s. Martnez

Companon took part in the excavation of several burials within the ruins of the

abandoned desert city of Chan Chan, just outside Trujillo. He sent many of the recovered

archaeological objects to Spain, and eventually published a description of his

archaeological ndings as the ninth and nal volume of his natural history of the Trujillo

region (Martnez Companon 1991). He assumed these were prehistoric, but several of

them were the burials of the sixteenth-century indigenous Chimu lords of this region,

buried in a mix of Spanish and indigenous clothing and grave goods (Cabello Carro 2003).

Martnez Companon was the rst to encounter, although unknown to him, the continuity

of burial practices on pre-Hispanic sacred sites into the early colonial period. Cabello

(2003: 96) suggests that before 1610 the campaign to end idolatry on the part of Andean

indigenous people was scattered and incomplete, and only after 1610 was there a thorough

clampdown on burial in non-Catholic cemeteries with traditional grave goods and, in

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 355

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

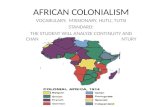

Figure 1 Map of South America with places mentioned in the text.

356 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

some cases, mummication practices. Colonial burial oerings at Chan Chan included

interesting metal objects (Rovira 1995) and glazed ceramic stirrup-spouted jars (Bushnell

1967 [1959]), both of which provide tantalizing clues as to the technological interchanges

between Spanish and early colonial Chimu artisans.

From Martnez Companon onwards, those who have excavated pre-Hispanic

cemeteries in the Andean region have often been confronted with sixteenth-century

colonial burials that resulted from ongoing use of these sacred places into the early

colonial period by indigenous groups. The discovery of post-contact mortuary remains

has increased in pace since the rst decades of the twentieth century, including contact-

period cemeteries in Argentina (Boman 1920; Duran and Novellino 2002; Novellino et

al. 2003; Reed 1918), Peru (Menzel 1967: 224), Colombia (Therrien 1996: 93) and Chile

(Berdichewsky Scher and Calvo de Guzman 1972). On the eastern slopes of the Andes

in Peru and Colombia mummication practices continued into the colonial period, in

one case as late as the eighteenth century (Cardenas Arroyo 1989, 1990; von Hagen

2002). These discoveries pale by comparison to the newly discovered cemetery at the

Puruchuco burial grounds, outside Lima, Peru. To date over 2000 mummies have been

recovered. Most are Inka (Late Horizon) in date, although a signicant number include

imported European goods, showing them in fact to be early colonial. Although not yet

published, the research eort of Guillermo Cock and team will provide a signicant

new data set on this incredibly rich example of early colonial Peruvian burial practices

(Cock Carrasco 2002; Murphy 2003). These colonial mummied remains have been

used in studies of pre-Columbian and historic genetics, from studies of blood types

thirty years ago (Allison et al. 1976, 1978) to recent work on Colombian historic

mummies by geneticists to look at DNA haplotypes from the region (Monsalve et al.

1996).

That pre-Hispanic cemeteries were eventually put out of use by Catholic authorities and

cultural change is clear, but archaeological excavation of later Catholic cemeteries is very

rare. Only Alberta Zucchi (1995, 1997) has undertaken a serious study of the development

of con and burial chamber styles throughout the colonial period, excavating a series of

cemeteries on San Carlos Island on the north coast of Venezuela.

Shifting rural landscapes

Spanish colonists in the Andes entered a landscape already heavily occupied by indigenous

peoples relying on farming economies, and tied to both village and urban lives. We can see

in the Andes an initial contact-period focus on Spanish settlement in places already

occupied by indigenous people. Some of these locations grew to be large colonial centres,

but others became abandoned as colonial economies and resettlement programs changed

the way people were distributed on the Andean landscape.

A few early Spanish domestic sites that were located on top of pre-Hispanic

occupations, and then quickly abandoned as more permanent settlements emerged, have

been excavated by archaeologists. These provide snapshots of early colonial life in the

region. In Peru, early Spanish colonial occupation levels were analysed from the top of

prehistoric mound sites outside Lima (Arrieta Alvarez 1975; Cardenas Martn 1970, 1971,

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 357

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

1973), including the amazing discovery of preserved documents and playing cards

(Cogorno Ventura 1970).

Colonial policies of reduccion throughout the Andes meant that rural villages were

relocated the better to control indigenous populations after the conquest. These

seventeenth- and eighteenth-century policies meant the abandonment of many early

colonial rural villages, a situation that has left early colonial village ruins scattered across

the landscape. One of the rst investigations of such a village was Styg Rydens work in

the Desaguadero Basin in Bolivia, where he excavated Inka period villages, but also came

across one early colonial village (Ryden 1947). Marion and Harry Tschopik excavated a

similar site on the western shores of Lake Titicaca (Tschopik 1950), while prehistorians

working on the south coast of Peru excavated two early colonial churches, one in the Acari

Valley (Menzel and Riddell 1986) and one at Sama (Trimborn 1981). In other regions the

continuity from pre-Hispanic through colonial landscapes has been emphasized, such as in

Neyla Castillos (1988) work in Antioquia, Colombia. Mary Van Burens (1996, 1997)

excavations at Torata Alta, in the Moquegua Valley of Peru, emphasized the early colonial

exchange of goods between villages at higher and lower elevations, and the relationship of

this to the Andean concept of vertical archipelagos. Karen Stotherts (Stothert et al. 1997)

work on rural farmsteads in the Santa Elena Peninsula of Ecuador is one of the only

studies to approach the rural transition from late colonial to early Republican Period

landscapes seriously from an archaeological perspective.

Colonial economic changes meant that in many rural villages the population remained

in place, but the subsistence economy underwent large changes. Several projects devoted

to faunal analysis of prehistoric domestic contexts have also analysed early historic faunal

assemblages, allowing us a glimpse into subsistence changes on sites occupied both before

and after the conquest. The earliest study of this type was Mario Sanojas (1968) work at

sixteenth-century indigenous village sites in the Quibor Valley of the northern Venezuelan

Andes, where faunal remains showed heavy reliance on hunted species and considerable

continuity between late prehistoric and early historic faunal assemblages. Susan DeFrance

(1996) analysed the fauna from the Torata Alta village in Bolivia, a later village site where

reliance on European domesticates was much greater than in similar contexts in the

Caribbean or Florida. We should not leap to the conclusion, however, that indigenous

domestic animals were quickly overwhelmed by Iberian replacements. At Lukurmata,

Bolivia, Karen Wise (1993) has found that late prehistoric shing economies were replaced

in the early colonial period by a heavier reliance on Andean camelids, showing that

colonial subsistence dynamics were locally and historically situated, and could shift

toward, rather than away from, Andean domesticates.

Large-scale agricultural production at haciendas, plantations and other rural facilities

has almost entirely escaped the attention of archaeologists. Despite the importance of such

facilities in the development of the colonial Andean economies, archaeologists have not

studied the large-scale landholding operations of colonial individuals and entities such as

the religious orders. The only exception has been the Moquegua Bodegas Project, directed

by Prudence Rice, which studied the system of colonial wineries in the Moquegua Valley

of south coastal Peru. The project began as an oshoot of the Osmore Drainage prehistory

project (Stanish and Rice 1989), which involved both North American and Peruvian

archaeologists. From 1985 to 1990 the Moquegua Bodegas participants tested a whole

358 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

series of wineries in the valley, and extensively excavated four of them (Rice 1995, 1996;

Smith 1997). Associated with these were kiln facilities for the production of large, coarse

earthenware storage and production vessels. The project excavated two of these ceramic

manufacturing centres (Rice and Van Beck 1993; Rice 1994). This was an exemplary

project, resulting in a multitude of publications on the well-analysed remains of the

wineries. Subsistence, trade and identity issues were all parts of the research agenda, which

should serve as a model for other studies of plantation agricultural sites throughout the

region.

Extractive industries

The Spanish Andean colonies were built on the mining industry. Historians of the colonial

Andes recognize the central role of the mining economy in the region (Craig and West

1994), and yet in the Andes colonial mines have received minimal archaeological attention.

Iain Mackay (1995) undertook surface survey of colonial gold-processing equipment at the

abandoned village of Maukallaqta, on the eastern Andean slopes of Bolivia, east of Lake

Titicaca. The excavation of nineteenth-century nitrate extraction sites in the Atacama

Desert of Northern Chile was undertaken by Gerda Alcaide and Bente Bittman (1984).

Karen Stothert (1994) has studied natural tar pits on the ground surface on the Santa

Elena Peninsula of Ecuador, the tar having been used since pre-Hispanic times as a sealant

and continuing in use up until the origins of the modern oil industry in the area in the early

twentieth century.

Conditions in the mines for the indigenous labourers were horrifying, and drew labour

from across huge sections of the rural Andes during the colonial period (Bakewell 1984).

This is poignantly demonstrated in the analysis of mummied colonial remains. Allison

(1979) studied sixty-seven mummies from a 1580 to 1650 cemetery near Ica, Peru, nding a

signicant decrease in lifespan compared to local pre-Hispanic demographics and a strong

absence of adult males, no doubt reecting the forced labour of the highland mines.

Fractures were 500 times more common than in prehistoric samples, presumably from

abuse and labour accidents. In a slightly earlier cemetery studied by the same team

(Munizaga et al. 1975), from Pica, in the northern Chilean desert, autopsies showed

incredibly high mercury levels, from patio processing of metals in mines, and

pneumoconiosis with emphysema, or black lung, in twelve of nineteen adults, due to

metal particles in the lungs. Such bodies are a sad reminder of the health impacts of forced

mine labour on indigenous colonial peoples.

Ceramic manufacturing

The manufacture of ceramics in the Andes was of very minor economic importance, but is

of the utmost importance to historical archaeologists, in order to source the materials

found in their excavations. Despite the urgency of research questions about colonial

ceramic manufacturing (Jamieson and Hancock 2004; Rovira 2001; Schavelzon 2000b;

Therrien et al. 2002), only a very few kiln sites have been excavated.

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 359

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

The Jesuit hacienda of Tierrabomba, outside Cartagena, was the site of a tile and

ceramic tableware manufacturing centre which was producing glazed wares by 1650 and

survived the Jesuit expulsion of 1767. This has had some preliminary excavation

conducted, but this has never been published (Therrien et al. 2002: 278). In Bogota the

excavation of a rened white earthenware factory (Therrien 2002b), which opened in the

1830s with British equipment and technicians and closed in the early 1900s, is a unique

example of archaeological investigation of rened ceramic production in the Andes.

Unglazed colonial coarse earthenwares are one of the least understood categories of

ceramics in the colonial Andes, produced largely in rural villages. Jaime Miasta Gutierrez

(1985) undertook a unique study of these wares in the excavation of ceramic waster dumps

in three villages that supplied Lima, Peru, with coarse earthenwares throughout the

colonial period. Ease of access to these types of sites is very dierent from in large urban

centres such as Lima, where Juan Mogrovejo (1996: 34) came across waster dumps from

colonial majolica production in construction backdirt in central Lima.

Andean colonial cities

Many Andean cities have retained their colonial street layouts, and extensive pieces of

religious, civil, military and domestic architecture. Despite the preservation of colonial

architecture in Andean cities, and recognition of these places as historically signicant,

urban archaeology is quite underdeveloped. Largely through historical accident, and often

related to the personal interests of a single local researcher, urban archaeology in the

Andes has been focused on Caracas in Venezuela (Sanoja Obediente and Vargas Arenas

2002), Cartagena and Bogota in Colombia (Therrien et al. 2002), Quito and Cuenca in

Ecuador (Buys 1997, Jamieson 2000b), Lima, Peru (Mogrovejo Rosales 1996) and

Mendoza, Argentina (Barcena 1993; Schavelzon 1998). The city of Buenos Aires must also

be mentioned, because, although it is not an Andean city geographically, the extensive

historical archaeology carried out there has been a strong inuence on the development of

historical archaeology in the Andes (Funari and Zarankin 2003; Schavelzon 1992, 2000a).

Much of the historical archaeology accomplished to date has been the result of the

restoration of impressive architecture in urban contexts. This has meant a focus on large-

scale projects of the colonial church and state. One of the more innovative studies has been

Emanuele Amodio et al.s (1997) survey of the road from the Caribbean port of La Guaira

up to the city of Caracas, Venezuela. The scale of the research was unusual, focusing on a

linear feature traversing a range of elevations. Archaeological excavation at several

roadside military and way stations explored the material culture of these facilities, and

extensive historical research resulted in comprehensive publication of the results of this

work, helping to illustrate the massive changes that the eighteenth-century Bourbon

Reforms brought to public and defense planning in the Andean colonies. The only work in

any way comparable to this is Colleen Beck et al.s (1983) excavation of a colonial

roadside way station in north coastal Peru, which was a much smaller project as part of

prehistoric work in the area.

Urban administrative buildings are obvious targets for restoration and alteration in

Andean cities. In Mendoza, Argentina, the citys layout was changed after the 1861

360 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

earthquake. The colonial cabildo, or city council, became a municipal slaughterhouse, then

an open market, and was abandoned in 1989. Urban renewal led to restoration, and

Roberto Barcena and Daniel Schavelzon undertook excavation to reveal the construction

history and material remains of the colonial cabildo buildings of that city (Barcena and

Schavelzon 1991). Colonial domestic sites in the Andes have not received anywhere near

the attention of large public architecture. The excavation of the Osambela House in Lima,

Peru, in the late 1970s was exemplary work for its time, with publication of faunal and

ceramic analyses (Flores Espinosa et al. 1981). In Bogota, Colombia, the Casa de los

Comuneros has been used as an example in Monica Therriens ongoing work on social

relations in colonial Colombia (Therrien 1999). In Caracas the house of independence

leader Juan Bautista Arismendi has been excavated and the results published as part of the

restoration of a church and music school built on the site (Sanoja Obediente et al. 1998).

Finally, in Cuenca, Ecuador, my own work has emphasized the relationship between

domestic material culture and the shifting nature of colonial identities (Jamieson 2000b).

Country houses

Urban elites in the colonial Andes desired rural escape as much as elites in other cities of

the period. Such properties, built largely for pleasure and relaxation, have survived

disproportionately in the archaeological record because of their rural locations. Most

thoroughly studied has been the Tarapaya hot springs, outside Potos, Bolivia. In the

seventeenth century Francisco de la Rocha owned an inn and country house here, visited

by the elite of the Potos mining community. Excavation by Mary Van Buren and analysis

of the recovered remains, including fauna, show that, although ceramics and other

household goods at this place of relaxation were largely locally made products, the

wealthy who visited here dined on Old World domesticates, showing the extent of the

market for traditional Spanish foodstus even in this high-elevation mining community

(DeFrance 2003; Van Buren 1999).

The hot springs at Tarapaya attracted people from Potos throughout the colonial

period, but country houses for relaxation, as opposed to agricultural production, became

much more common for wealthy urbanites after 1780. The Quinta de Bolivar outside

Bogota is a good example, founded in 1800 as a rural casa de recreo, and given to Simon

Bolvar in 1820. It remained his house until converted to industrial purposes in the late

nineteenth century. Now a museum, restoration eorts led to excavation in the late 1990s

that remain unpublished (Therrien et al. 2002: 30). The nineteenth-century home of Jose

Ozamis outside Mendoza, Argentina, was a comparable study of a rural quinta as part of

its conversion into a local museum (Abal et al. 1996).

The Catholic Church

The Catholic Church was a key religious and political institution in the Spanish

administration of the Andean colonies. The preservation of church architecture from the

colonial period has been a serious concern for cultural resource managers in the region,

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 361

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

with several cities designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites largely on the basis of

surviving colonial religious architecture. This has also been a major emphasis for historical

archaeologists in the region. Much of the earliest, and most extensive, historical

archaeology done in Andean cities was the direct result of eorts to restore, stabilize

and research the history of churches, monasteries and convents in colonial Andean cities.

This is an ongoing eort that continues with projects operating today, to the extent that

such research could be said to be one of the core areas of Andean historical archaeology.

Large urban church facilities are the jewels of many urban historic districts in the

region. The rst cathedral in Bogota was the subject of Monika Therriens (1995) above-

ground archaeology when it underwent recent restoration. In Caracas the rst church in

the city, dating to the 1560s to 1650s, has been located and excavated (Sanoja Obediente et

al. 1998). One of the largest projects on an Andean monastery has been that on the Jesuit

property called the San Francisco site in Mendoza, Argentina. This property was the

Jesuit Colegio de la Inmaculada Concepcion and Loreto Church from 1608 until the Jesuit

expulsion in 1767, when it became a Franciscan monastery. Destroyed in the 1861

earthquake, the site became an early twentieth-century municipal park, with picturesque

ruins, gardens and an articial lake. Mid-1990s restoration of the park brought about an

extensive archaeological project, which has been well-reported, and includes faunal

analysis, which is a step rarely achieved in Andean projects to date (Schavelzon 1998;

Silveira 1998).

Unfortunately, the urgency of architectural restoration of many urban church

properties has led to extensive archaeological excavation without the publication of

research results. In Venezuela the sixteenth-century Franciscan monastery in Caracas was

excavated, but published research results are minimal (Sanoja Obediente and Vargas

Arenas 1996, 2002: 137). The hospital of San Pablo, in a peripheral neighbourhood of

Caracas, was in operation by 1602, and continued to operate as a twelve-bed facility until

expansion in the Bourbon period, and then its eventual closure in the mid-nineteenth

century. Restoration of a theatre currently located on the property led to large-scale

excavation of the facilities, including the discovery of re-deposited human remains from

the heavily damaged hospital cemetery (Vargas Arenas et al. 1998).

Monasteries in Cartagena, Bogota, and Leiva, Colombia (Therrien 1996; Therrien et al.

2002: 2531), and in Quito, Ecuador, have had extensive archaeological work carried out,

but without (to date) the nal step of publication (Buys 1997). The faunal remains from

the Franciscan and Dominican monasteries in Quito have, however, received thorough

treatment (Gutierrez Usillos and Iglesias Aliaga 1996). The situation in Peru is similar,

with the monasteries of Santo Domingo, the Jesuit Compana de Jesus, and the

Mercedarian la Merced monasteries in Cuzco all excavated in the 1980s and 1990s, with no

publication of the results, and even the loss of the government reports on these important

facilities (Mogrovejo Rosales 1996: 1516).

In contrast to Mesoamerica and North America (Graham 1998), extensive urban

archaeology on convents and monasteries is not paralleled in the Andes by work on rural

missions. Only on the eastern slopes of the Andes, where Amazonian peoples underwent

centuries of missionization by various Catholic orders (Merino and Newson 1994), have

archaeologists studied this type of contact site (Raymond 1976; Myers 1990). Myers study

of the late colonial/early Republican period Franciscan mission in the Upper Ucayali

362 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

River system shows how little imported material culture came down the eastern slopes of

the Andes until quite late in the nineteenth century.

Death in the cloisters

Excavation in urban Andean monasteries and churches has inevitably led to the discovery

of large-scale mortuary features. Burial in colonial cities took place under church oors, in

cloisters and other parts of monasteries, from the sixteenth century until the passage of

burial reform in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Remains may be

primary burials of single individuals, secondary reburials in bundles or, frequently,

common ossuaries where the remains of many individuals are mixed. The analysis of these

remains requires the work of a qualied physical anthropologist, an ideal which is not

always met when large-scale mortuary contexts are uncovered in the Andes.

Perhaps the largest, and an exemplary, study of this kind is the work of Douglas

Ubelaker in Quito. After decades of work on prehistoric Ecuadorian burial samples, the

excavation of the San Francisco Monastery in Quito in 198793 provided Ubelaker the

opportunity to study a large colonial burial population. The excavation results from the

monastery remain unpublished, but Ubelaker (1994b; Ubelaker and Ripley 1999) has

published detailed studies of the human remains recovered. These date to the colonial

Franciscan occupation of the site, and number over 200 individuals. Combined with

samples from the Dominican monastery and the Bethlemite colonial hospital in the same

city (Ubelaker and Rousseau 1993), Ubelaker has used this colonial Quito population in

comparative research on the craniometry of NewWorld samples, and comparisons between

prehistoric and historic disease and demography in Ecuador (Ross et al. 2002; Ubelaker

1994a, 1995; Ubelaker and Newson 2002). Much of the archaeology from these sites in

Quito remains unpublished, yet the human remains have been comprehensively analysed.

The opposite is true of the Jesuit Monastery in Mendoza, Argentina, where the

archaeological materials have been thoroughly analysed (Schavelzon 1998), but the large

ossuary under the church oor (Cortegoso et al. 1998) has not been analysed by a physical

anthropologist.

Such demographic studies of mass graves can be contrasted with work in Lima, where a

cult of sorts appears to surround the identication of the famous in the human remains

encountered in colonial crypts. The uncontested recovery and analysis of the remains of a

seventeenth-century viceroy in the Lima Cathedral crypt (Guillen Oneeglio 1993) stand in

sharp contrast to the debate which erupted over the supposed identication of the remains

of Francisco Pizarro from the crypts of the same church in 1977 (Mogrovejo Rosales 1996:

19; San Cristobal Sebastian and Guillen Guillen 1986). The search continues for the

mummies of the last Inka rulers, brought to the San Andres Hospital in Lima in the 1560s,

and presumably placed in the crypts beneath the hospital. Jose de la Riva-Aguero

attempted to excavate these crypts in 1937 in order to recover the mummies, but quickly

gave up (Mogrovejo Rosales 1996: 12; Riva-Aguero 1966 [1938]), and now a new team of

historians and archaeologists has undertaken a ground-penetrating radar survey of the

hospital property in an initial step toward opening crypts to look for these long-sought

personages (McCaa et al. 2004).

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 363

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Conclusions

Historical archaeology in the Andes has emerged as a sub-discipline over the past twenty

years. Many types of sites, and many research questions, have now been addressed by

professional archaeologists. There are, however, many areas left untouched. Recent

surveys of African Diaspora archaeology note the extension of research to Brazilian sites

(Orser and Funari 2001; Weik 1997) and to Buenos Aires (Schavelzon 2003). The presence

of large numbers of enslaved and free African peoples in the Andes throughout the

colonial period and beyond has not yet been translated into archaeological research on the

African Diaspora anywhere in the region. In a similar fashion, gendered approaches, and

studies of sexuality, have become an important focus in historical archaeology on a global

scale (McEwan 1991; Schmidt and Voss 2000), and yet in the Andes such a research focus

has yet to be tried in any serious fashion (but cf. Jamieson 2000a).

One of the greatest lacunae in the literature is in regard to the scientic analysis of

recovered collections. Flotation and palynology seem non-existent in colonial archaeology

in the Andes, despite excellent studies of these remains in prehistoric contexts in the region

(Hastorf 1993; Piperno and Pearsall 1998). The analysis of faunal remains from colonial

sites has shown excellent results, and it is hoped that in the near future macrobotanical and

palynological analyses of colonial contexts will become the norm in the region, although a

lack of trained specialists in these analyses is an obvious hindrance to them becoming

standard practices.

More important than addressing particular themes or methods is the simple need for

better communication among researchers. Many researchers rarely, if ever, cite work

accomplished on similar themes in the other Andean nations. The parochialism of working

within a national context, with little chance for international exchange of ideas, may be a

problem for some. In the case of foreign projects, a lack of any sincere attempt to gain

control of local literatures in the Spanish language may be at fault, as has been pointed out

for Latin America more generally by Jack Williams and Patricia Fournier (1996). What

emerges most glaringly, however, is the scattered nature of publication of Andean

historical archaeology. Without any journals or newsletters devoted to the topic, Andean

historical archaeologists publish in English-language journals in North America, or in

journals of limited circulation published in the various Andean nations. None of these

venues is inherently bad, but the scattering of publications on the topic does little to

improve the fractured nature of the sub-discipline. The only exception has been Stanley

Souths Historical Archaeology in Latin America series, which has allowed a variety of

researchers to publish results of research expeditiously in an aordable, multilingual

venue. It is dicult to say whether Andean historical archaeology, as with other

archaeologies (Kohl and Fawcett 1995; Schmidt and Patterson 1995), suers from

nationalism or benets by it. National pride has created much of the historical

archaeology that has taken place in the region, and yet the lack of citation of other

Andean researchers material in various studies may go beyond issues of lack of access to

bibliographic material and enter the realm of parochialism.

On a more positive note, the entire research eort in Andean historical archaeology is

maintained by no more than fteen principal investigators, yet these individuals make

huge dierences in their own countries, and international interchange between them is

364 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

occurring at an ever-increasing pace. A decade ago Richard Schaedel (1992) could lament

the almost complete lack of published Andean historical archaeology. This is no longer the

case. Although the situation still appears underdeveloped, the reality is that single

researchers have made huge dierences regionally, and over the next decade these eorts

are sure to coalesce into an increasingly dynamic, well-published and internationalized

eort to understand the colonial period in the Andes from an archaeological perspective.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Meridith Sayre, Gina Michaels and Michael St. Denis for their help with

the research. As always, I want to thank Laurie Beckwith for her unagging support. The

interlibrary loan sta at the Bennett Library, Simon Fraser University, was a great help in

retrieving much of the material used here. My own research is conducted with nancing

from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, British Columbia

E-mail: [email protected]

References

Abal, C., Chiavazza, H., Contreras, O., Puebla, L. and Zorilla, V. 1996. Arqueologa historica, derescate, etc.: la casa solarieg de Don Jose A. Ozamis, depto. de Maipu, prov. de Mendoza,Argentina. Historical Archaeology in Latin America, 16: 95102.

Acuto, F. A. and Zarankin, A. 1999. Introduccion: aun sedientos. In Sed non satiata: teora social enla arqueologa Latinoamericana contemporanea (eds A. Zarankin and F. A. Acuto). Buenos Aires:Ediciones del Tridente, pp. 715.

Alcaide, G. and Bittmann, B. 1984. Historical archaeology in abandoned nitrate ocinas innorthern Chile: a preliminary report. Historical Archaeology, 18: 5275.

Allen, C. J. 1988. The Hold Life Has: Coca and Cultural Identity in an Andean Community.Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Allison, M. J. 1979. Paleopathology in Peru. Natural History, 88: 7482.

Allison, M. J., Hossaini, A. A., Castro, N., Munizaga, J. and Pezzia, A. 1976. ABO blood groups in

Peruvian mummies, I: an evaluation of techniques. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 44:5561.

Allison, M. J., Hossaini, A. A., Munizaga, J. and Fung, R. 1978. ABO blood groups in Chilean andPeruvian mummies, II: results of agglutination-inhibition technique. American Journal of PhysicalAnthropology, 49: 13942.

Amodio, E., Navarrete Sanchez, R. and Rodrguez Yilo, A. C. 1997. El Camino de los Espanoles:aproximaciones historicas y arqueologicas al Camino Real Caracas-La Guaira en la epoca colonial.Caracas, Venezuela: Instituto del Patrimonio Cultural.

Andrien, K. J. 2001. Andean Worlds: Indigenous History, Culture, and Consciousness under SpanishRule, 15321825. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 365

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Arrieta Alvarez, A. 1975. Primeros Hallazgos en Huaca Casa Rosada (Loza, Vidrio, Ceramica

Vidriada). Boletn del Seminario de Arqueologa [Ponticia Univ. Catolica del Peru, Lima], 1516:15966.

Bakewell, P. J. 1984. Miners of the Red Mountain: Indian Labor in Potos, 15451650. Albuquerque,NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Barcena, J. R. 1993. Las investigaciones arqueologicas e historicas y las posibilidades economicas del

rescate y valorizacion del patrimonio cultural. Revista de la Bolsa de Comercio de Mendoza[Mendoza, Argentina], 351: 34.

Barcena, J. R. and Schavelzon, D. 1991. El cabildo de Mendoza: arqueologa e historia para surecuperacion. Mendoza, Argentina: Municipalidad de Mendoza.

Bastien, J. W. 1978.Mountain of the Condor: Metaphor and Ritual in an Andean Ayllu. St. Paul, MN:West.

Beck, C. M., Deeds, E. E., Pozorski, S. and Pozorski, T. 1983. Pajatambo: an 18th century roadside

structure in Peru. Historical Archaeology, 17: 5468.

Benavides, H. O. 2001. Returning to the source: social archaeology as Latin American philosophy.

Latin American Antiquity, 12: 355 70.

Berdichewsky Scher, B. and Calvo de Guzman, M. 1972. Excavaciones en cementerios indgenas de

la region de Calagquen. In Congreso de Arqueologa Chilena, VI, Arica, Chile, 1971. Actas. Santiago,Chile: Editorial Universitaria, pp. 52958.

Boman, E. 1920. Cementerio indgena de Viluco (Mendoza) posterior a la Conquista. Anales del

Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Buenos Aires, 30: 50162.

Bushnell, G. 1967 [1959]. Some Post-Columbian whistling jars from Peru. In Peruvian Archaeology:

Selected Readings (eds J. H. Rowe and D. Menzel). Palo Alto, CA: Peek Publications, pp. 2437.

Buys, J. 1997. Monumentos y fragmentos: arqueologa historica en el Ecuador. In Approaches to the

Historical Archaeology of Mexico, Central and South America (eds J. L. Gasco, G. C. Smith and P.Fournier Garca). Los Angeles: The Institute of Archaeology, University of California, pp. 11120.

Cabello Carro, P. 2003. Mestizaje y ritos funerarios en Trujillo, Peru, segun las antiguas colecciones

Reales Espanolas. In Iberoamerica Mestiza: encuentro de pueblos y culturas. Madrid: Seacex, pp. 85102.

Cardenas Arroyo, F. 1989. La momicacion indgena en Colombia. Boletin del Museo del Oro, 25:1203.

Cardenas Arroyo, F. 1990. La momia de Pisba. Boletn del Museo del Oro, 27: 213.

Cardenas Martn, M. 1970. Ocupacion espanola de una huaca del valle de Lima: casa en laplataforma superior de la Huaca Tres Palos. Boletn del Seminario de Arqueologa [Lima], 5: 409.

Cardenas Martn, M. 1971. Huaca Palomino, Valle del Rmac: fragmentera vidriada na condecoracion en colores. Boletn del Seminario de Arqueologa [Lima], 10: 617.

Cardenas Martn, M. 1973. Ceramica de transicion: Huaca Palomino, Valle del Rimac. Boletn delSeminario de Arqueologa [Lima], 14: 304.

Castillo E. N. 1988. Complejos arqueologicos y grupos etnicos del siglo XVI en el occidente deAntioquia. Boletn del Museo del Oro, 20: 1634.

Cock Carrasco, G. 2002. Inca rescue. National Geographic, May: 7891.

Cogorno Ventura, G. 1970. Documentos y naipes hallados en las excavaciones de la Huaca Tres

Palos, Pando, Lima. Boletn del Seminario de Arqueologa [Lima], 5: 139.

Colloredo-Mansfeld, R. 1998. Dirty Indians, radical Indgenas, and the political economy of social

dierence in modern Ecuador. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 17: 185205.

366 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Congreso Nacional de Arqueologa Historica (ed.) 2002. Arqueologa Historica Argentina: Actas del

1er Congreso Nacional de Arqueologa Historica. Buenos Aires: Corregidor.

Cortegoso, V., Chiavazza, H. and Pelagatti, O. 1998. Muerte, muertos y huesos en las ruinas. In Las

Ruinas de San Francisco (ed. D. Schavelzon). Mendoza, Argentina: Municipalidad de Mendoza, pp.27594.

Craig, A. K. and West, R. C. 1994. In Quest of Mineral Wealth: Aboriginal and Colonial Mining and

Metallurgy in Spanish America. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University.

DeFrance, S. D. 1996. Iberian foodways in the Moquegua and Torata Valleys of Southern Peru.

Historical Archaeology, 30: 2048.

DeFrance, S. D. 2003. Diet and provisioning in the High Andes: a Spanish colonial settlement on the

outskirts of Potos, Bolivia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 7: 99125.

Duran, V. and Novellino, P. 2002. Vida y muerte en la frontera del imperio espanol: estudiosarqueologicos y bio-antropologicos en un cementerio indgena post-contacto del centro-oeste de

Argentina. Anales de Arqueologa y Etnologa [Argentina], 545.

Flores Espinosa, I., Garca Soto, R. and Huertas V. L. 1981. Investigacion arqueologica-historica de

la Casa Osambela (o de Oquendo), Lima. Lima, Peru: Instituto Nacional de Cultura.

Fournier Garca, P. 1999. La arqueologa social Latinoamericana: caracterizacion de una posicion

teorica marxista. In Sed non satiata: teora social en la arqueologa Latinoamericana contemporanea(eds A. Zarankin and F. A. Acuto). Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Tridente, pp. 1732.

Funari, P. P. A. 1996. Historical archaeology in Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina. World

Archaeological Bulletin, 7: 5162.

Funari, P. P. A. 1997. Archaeology, history, and historical archaeology in South America.

International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 1: 189206.

Funari, P. P. A. and Zarankin, A. 2003. Social archaeology of housing from a Latin American

perspective. Journal of Social Archaeology, 3: 2345.

Gomez Romero, F. 2002. Philosophy and historical archaeology: Foucault and a singulartechnology of power development at the borderlands of nineteenth-century Argentina. Journal of

Social Archaeology, 2: 40229.

Gorriti Ellenbogen, G. 1999. The Shining Path: A History of the Millenarian War in Peru. Chapel

Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Graham, E. 1998. Mission archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 27: 2562.

Guillen Oneeglio, S. 1993. Identicacion y estudio de los restos del virrey Conde de la Monclova enla cripta arqobispal de la Catedral de Lima. Sequilao: Revista de arte, historia y sociedad [Lima], 2:715.

Guthertz Lizarraga, K. 1999. From social archaeology to national archaeology: up fromdomination. American Antiquity, 64: 3638.

Gutierrez Usillos, A. and Iglesias Aliaga, J. R. 1996. Identicacion y analisis de los restos de faunarecuperados en los conventos de San Francisco y Santo Domingo de Quito (siglos XVIXIX).

Revista Espanola de Antropologa Americana, 26: 77100.

Hastorf, C. A. 1993. Agriculture and the Onset of Political Inequality before the Inka. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Isbell, W. H. and Silverman, H. (eds) 2002. Andean Archaeology, 2 vols. New York: KluwerAcademic/Plenum.

Jamieson, R. W. 2000a. Dona Luisa and her two houses. In Lines that Divide: HistoricalArchaeologies of Race, Class, and Gender (eds J. A. Delle, S. A. Mrozowski and R. Paynter).

Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, pp. 14267.

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 367

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Jamieson, R. W. 2000b. Domestic Architecture and Power: The Historical Archaeology of Colonial

Ecuador. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Jamieson, R. W. and Hancock, R. G. V. 2004. Neutron activation analysis of colonial ceramics from

Southern Highland Ecuador. Archaeometry, 46: 56983.

Kohl, P. L. and Fawcett, C. P. (eds) 1995. Nationalism, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Larson, B. and Harris, O. (eds) 1995. Ethnicity, Markets and Migration in the Andes: At theCrossroads of History and Anthropology. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Lumbreras, L. G. 1974. La arqueologa como ciencia social. Lima, Peru: Ediciones Histar.

McCaa, R., Nimlos, A. and Hampe Martnez, T. 2004. Why blame smallpox? The death of the IncaHuayna Capac and the demographic destruction of Tawantinsuyu (ancient Peru). Conference paper,American Historical Association, Washington, DC, 2004.

McEwan, B. G. 1991. The archaeology of women in the Spanish New World. HistoricalArchaeology, 25: 3341.

Mackay, W. I. 1995. Gold extraction equipment at Maukallqta [sic]: the merging of indigenous andSpanish colonial technologies. In Trade and Discovery: The Scientic Study of Artefacts from Post-Medieval Europe and Beyond (eds D. R. Hook and D. R. M. Gaimster). London: British Museum

Press, pp. 15970.

Martnez Companon, B. J. 1991. Trujillo del Peru en el siglo XVIII, 9 vol. facsimile edition. Madrid:Ediciones de Cultura Hispanica.

Masuda, Y., Shimada, I. and Morris, C. 1985. Andean Ecology and Civilization: An InterdisciplinaryPerspective on Andean Ecological Complementarity. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Menzel, D. 1967. The Inca occupation of the south coast of Peru. In Peruvian Archaeology: SelectedReadings (eds J. H. Rowe and D. Menzel). Palo Alto, CA: Peek Publications, pp. 21734.

Menzel, D. and Riddell, F. A. 1986. Archaeological Excavations at Tambo Viejo, Acari Valley, Peru,1954. Sacramento, CA: California Institute for Peruvian Studies.

Merino, O. and Newson, L. A. 1994. Jesuit missions in Spanish America: the aftermath of theexpulsion. Revista de Historia de America, 118: 732.

Miasta Gutierrez, J. 1985. Arqueologa historica en Huarochiri: Santo Domingo de los Olleros, SanJose de Los Chorrillos y San Lorenzo de Quinti. Lima, Peru: Universidad Nacional Mayor de SanMarcos.

Mogrovejo Rosales, J. D. 1996. Arqueologa urbana de evidencias coloniales en la ciudad de Lima.Lima, Peru: Instituto Riva-Aguero.

Monsalve, M. V., Cardenas Arroyo, F., Guhl, F., Delaney, A. D. and Devine, D. V. 1996.Phylogenetic analysis of mtDNA lineages in South American mummies. Annals of Human Genetics,60: 293303.

Munizaga, J., Allison, M. J., Gerszten, E. and Klurfeld, D. M. 1975. Pneumoconiosis in Chileanminers of the 16th century. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 51: 128193.

Murphy, M. 2003. From bare bones to mummied: insights from an Inca cemetery. Expedition, 45:57.

Myers, T. P. 1990. Sarayacu: Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Investigations of a Nineteenth-Century Franciscan Mission in the Peruvian Montana. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Novellino, P., Duran, V. and Prieto, C. 2003. Capiz Alto: aspectos bioarqueologicos y arqueologicosdel cementerio indgena de epoca post-contacto (provincia de Mendoza, Argentina). Paleopatologa,1: 116.

368 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Orser, C. E. Jr. and Funari, P. P. A. 2001. Archaeology and slave resistance and rebellion. World

Archaeology, 33: 6172.

Ortiz-Troncoso, O. R. 1976. A 16th century Hispanic harbour in the Strait of Magellan, South

America. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration, 5: 1769.

Oyuela-Caycedo, A., Anaya, A. A., Elera, C. G. and Valdez, L. M. 1997. Social archaeology in LatinAmerica? Comments to T. C. Patterson. American Antiquity, 62: 36574.

Patterson, T. C. 1994. Social archaeology in Latin America: an appreciation. American Antiquity, 53:17.

Piperno, D. R. and Pearsall, D. M. 1998. The Origins of Agriculture in the Lowland Neotropics. SanDiego, CA: Academic Press.

Politis, G. G. 1995. The socio-politics of the development of archaeology in Hispanic SouthAmerica. In Theory in Archaeology: A World Perspective (ed. P. J. Ucko). London: Routledge, pp.197235.

Politis, G. G. 2003. The theoretical landscape and the methodological development of archaeologyin Latin America. American Antiquity, 68: 24572.

Raymond, J. S. 1976. Late prehistoric and historic settlements in the upper montana of Peru. InUniversity of Calgary Archaeological Association Annual Conference Proceedings No. 6. Calgary, AB:

Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary, pp. 20514.

Reed, C. 1918. Cementerio indgena postcolombiano de Viluco, provincia de Mendoza (comunica-cion preliminar presentada por Eric Boman). Physis [Buenos Aires], 4: 946.

Rice, P. 1994. The Kilns of Moquegua, Peru: technology, excavations, and functions. Journal ofField Archaeology, 21: 32544.

Rice, P. 1995. Wine and local Catholicism in colonial Moquegua, Peru. Colonial Latin AmericanHistorical Review, 4: 369404.

Rice, P. 1996. The archaeology of wine: the wine and brandy haciendas of Moquegua, Peru. Journalof Field Archaeology, 23: 187204.

Rice, P. and Van Beck, S. 1993. The Spanish colonial kiln tradition of Moquegua, Peru. HistoricalArchaeology, 27: 6581.

Riva-Aguero, J. d. l. 1966 [1938]. Sobre las momias de los Incas. In Estudios de la historia Peruana:las civilizaciones primitivas y el Imperio Incaico, Vol. 5 (ed. C. Pacheco Velez). Lima, Peru: PonticiaUniversidad Catolica del Peru, pp. 393400.

Ross, A. H., Ubelaker, D. H. and Falsetti, A. B. 2002. Craniometric variation in the Americas.Human Biology, 74: 80718.

Rovira, B. E. 2001. Presencia de mayolicas Panamenas en el mundo colonial: algunasconsideraciones acerca de su distribucion y cronologa. Latin American Antiquity, 12: 291303.

Rovira, S. 1995. New native metallurgical technology after Hispanic contact in Peru. In Trade andDiscovery: The Scientic Study of Artefacts from Post-Medieval Europe and Beyond (eds D. R. Hookand D. R. M. Gaimster). London: British Museum Press, pp. 299308.

Ryden, S. 1947. Archaeological Researches in the Highlands of Bolivia. Goteborg, Sweden: ElandersBoktryckeri Aktiebolog.

Salman, T. and Zoomers, E. B. (eds) 2003. Imaging the Andes: Shifting Margins of a Marginal World.Amsterdam: Aksant.

San Cristobal Sebastian, A. and Guillen Guillen, E. 1986. La ccion del esqueleto de Pizarro. Lima,Peru: Universidad Ricardo Palma.

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 369

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Sanhueza Tapia, J. A. and Olmos Figueroa, O. G. 1981. Usamaya I: cementerio indgena en Isluga,

altiplano de Iquique, 1 Region, Chile. Chungara, 8: 16987.

Sanoja Obediente, M. 1968. Ethnohistorical evaluation of zoological remains from two archeological

sites in Western Venezuela. In International Congress for the Study of Pre-Columbian Cultures in theLesser Antilles, II, Barbados, July 2428, 1967: Proceedings, pp. 10814.

Sanoja Obediente, M. 1978. Proyecto Orinoco: excavacion en el sitio arqueologico de los Castillos de

Guyana, Territorio Federal Delta Amacuro, Venezuela. In International Congress for the Study ofPre-Columbian Cultures of the Lesser Antilles, VII, Montreal, Canada, 1978: Proceedings, Montreal,Quebec: Universite de Montreal, Centre de Recherches Carabes, pp. 15768.

Sanoja Obediente, M. and Vargas Arenas, I. 1978. Antiguas formaciones y modos de produccionvenezolanos. Caracas, Venezuela: Monte Avila Editores.

Sanoja Obediente, M. and Vargas Arenas, I. 1996. Tendencias del proceso urbano en las provinciasde Caracas y Guayana, siglos XVIXIX: el modo de vida colonial venezolano. Revista deArqueologa Americana, 11: 5777.

Sanoja Obediente, M. and Vargas Arenas, I. 2002. El agua y el poder: Caracas y la formacion delestado colonial Caraqueno, 15671700. Caracas, Venezuela: Banco Central de Venezuela.

Sanoja Obediente, M., Vargas Arenas, I., Alvarado, G. and Montilla, M. 1998. Arqueologa deCaracas, tomo 1, Escuela de Musica Jose Angel Lamas. Caracas, Venezuela: Academia Nacional de

la Historia.

Schaedel, R. P. 1992. The archaeology of the Spanish colonial experience in South America.Antiquity, 66: 21642.

Schavelzon, D. (ed.) 1992. La arqueologa urbana en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor deAmerica Latina.

Schavelzon, D. (ed.) 1998. Las ruinas de San Francisco: arqueologa e historia. Mendoza, Argentina:Municipalidad de Mendoza, Editorial Tintar.

Schavelzon, D. 2000a. The Historical Archaeology of Buenos Aires: A City at the End of the World.New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Schavelzon, D. 2000b. Historias del comer y del beber en Buenos Aires: arqueologa historica de laVajilla de Mesa. Buenos Aires: Aguilar Argentina.

Schavelzon, D. 2003. Buenos Aires negra: arqueologa historica de una ciudad silenciada. BuenosAires: Emece Editores.

Schmidt, P. R. and Patterson, T. C. (eds) 1995. Making Alternative Histories: The Practice ofArchaeology and History in Non-Western Settings. School of American Research Advanced SeminarSeries. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Schmidt, R. A. and Voss, B. L. (eds) 2000. Archaeologies of Sexuality. London: Routledge.

Silveira, M. 1998. Zooarqueologa del Templo de San Francisco. In Las Ruinas de San Francisco (ed.

D. Schavelzon). Mendoza, Argentina: Municipalidad de Mendoza, pp. 33135.

Skar, H. O. 1982. The Warm Valley People: Duality and Land Reform among the Quechua Indians of

Highland Peru. New York: Columbia University Press.

Smith, G. C. 1997. Hispanic, Andean, and African inuences in the Moquegua Valley of SouthernPeru. Historical Archaeology, 31: 7483.

Stanish, C. and Rice, D. S. 1989. The Osmore Drainage, Peru: an introduction to the work of thePrograma Contisuyu. In Ecology, Settlement and History in the Osmore Drainage, Peru (eds D. S.

Rice, C. Stanish and P. R. Scarr). Oxford: BAR International Series 545, i, pp. 114.

Starn, O. 1991. Missing the revolution: anthropologists and the war in Peru. Cultural Anthropology,

6: 6391.

370 Ross W. Jamieson

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Stothert, K. E. 1994. Early petroleum extraction and tar-boiling in coastal Ecuador. In In Quest of

Mineral Wealth: Aboriginal and Colonial Mining and Metallurgy in Spanish America (eds A. K. Craigand R. C. West). Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University.

Stothert, K. E., Gross, K., Fox, A. and Sanchez Mosquera, A. 1997. Settlements and ceramics of theTambo River, Ecuador, from the early nineteenth century. In Approaches to the HistoricalArchaeology of Mexico, Central and South America (eds J. L. Gasco, G. C. Smith and P. FournierGarca). Los Angeles, CA: The Institute of Archaeology, University of California, pp. 12132.

Therrien, M. 1995. Terremotos, movimientos sociales y patrones de comportamiento cultural:arqueologa en la cubierta de la catedral primada de Bogota. Revista Colombiana de Antropologa,

32: 14783.

Therrien, M. 1996. Persistencia de practicas indgenas durante la Colonia en el Altiplano

cundiboyacense. Boletn Museo del Oro [Bogota], 40: 8999.

Therrien, M. 1999. Bases para una nueva historia del patrimonio cultural: un estudio de caso enSantafe de Bogota. Fronteras de la Historia [Colombia], 3.

Therrien, M. 2002a. Estilos de vida en la Nueva Granada: teora y practica en la arqueologahistorica de Colombia. Arqueologa de Panama La Vieja: Avances de investigacion, 2: 1938.

Therrien, M. 2002b. Loza na para Bogota: una fabrica de loza del siglo XIX. Revista deAntropologa y Arqueologa [Bogota], 13: 199228.

Therrien, M., Uprimny, E., Lobo Guerrero, J., Salamanca, M. F., Gaitan, F. and Fandino, M. 2002.Catalogo de ceramica colonial y republicana de la Nueva Granada: produccion local y materiales foraneos(Costa Caribe, Altiplano Cundiboyacense Colombia). Bogota, Colombia: Banco de la Republica.

Trawick, P. B. 2003. The Struggle for Water in Peru: Comedy and Tragedy in the Andean Commons.Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Trimborn, H. 1981. Sama. St. Augustin, Germany: Haus Volker/Kulturen, Anthropos-Institut.

Tschopik Jr, H. 1950. An Andean ceramic tradition in historical perspective. American Antiquity, 15:196218.

Ubelaker, D. H. 1994a. The biological impact of European contact in Ecuador. In In the Wake of

Contact: Biological Responses to Conquest (eds C. S. Larsen and G. R. Milner). New York: Wiley-Liss, pp. 14760.

Ubelaker, D. H. 1994b. Biologia de los restos humanos hallados en el Convento de San Francisco deQuito, Ecuador. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Ubelaker, D. H. 1995. Osteological and archival evidence for disease in historic Quito, Ecuador. InGrave Reections: Portraying the Past through Cemetery Studies (eds S. R. Saunders and A.Herring). Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press, pp. 22339.

Ubelaker, D. H. and Newson, L. A. 2002. Patterns of health and nutrition in prehistoric and historicEcuador. In The Backbone of History, Health and Nutrition in the Western Hemisphere (eds R. H.Steckel and J. C. Rose). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 34374.

Ubelaker, D. H. and Ripley, C. E. 1999. The Ossuary of San Francisco Church, Quito, Ecuador:Human Skeletal Biology. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Ubelaker, D. H. and Rousseau, A. 1993. Human remains from Hospital San Juan de Dios, Quito,Ecuador. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 83: 18.

Valdez, L. M. 2004. La losofa de la arqueologa de America Latina. In Teora arqueologica enAmerica del Sur (eds G. G. Politis and R. Peretti). Olavarra, Argentina: Ediciones Incuapa, pp. 12910.

Van Buren, M. 1996. Rethinking the vertical archipelago: ethnicity, exchange and history in thesouth-central Andes. American Anthropologist, 98: 33851.

Colonialism, social archaeology and lo Andino 371

-

Dow

nloa

ded

By:

[Uni

vers

ity C

olle

ge L

ondo

n] A

t: 15

:47

8 N

ovem

ber 2

007

Van Buren, M. 1997. Continuity or change? Vertical archipelagos in southern Peru during the Early

Colonial Period. In Approaches to the Historical Archaeology of Mexico, Central and South America(eds J. L. Gasco, G. C. Smith and P. Fournier Garca). Los Angeles, CA: The Institute ofArchaeology, University of California, pp. 15564.

Van Buren, M. 1999. Tarapaya: an elite Spanish residence near colonial Potos in comparativeperspective. Historical Archaeology, 33: 10822.

Vargas Arenas, I. and Sanoja Obediente, M. 1993. Historia, identidad, y poder. Caracas, Venezuela:Fondo Editorial Tropykos.

Vargas Arenas, I., Sanoja Obediente, M., Alvarado, G. and Montilla, M. 1998. Arqueologa deCaracas, tomo 2, San Pablo, Teatro Municipal. Caracas, Venezuela: Academia Nacional de laHistoria.

von Hagen, A. 2002. Chachapoya iconography and society at Laguna de los Condores, Peru. InAndean Archaeology II: Art, Landscape and Society (eds H. Silverman and W. H. Isbell). New York:Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Weik, T. 1997. The archaeology of maroon societies in the Americas: resistance, cultural continuity,and transformation in the African diaspora. Historical Archaeology, 31: 8192.

Weismantel, M. J. 1991. Maize beer and Andean social transformations: drunken Indians, breadbabies, and chosen women. MLN, 106: 86179.

Williams, J. S. and Fournier Garca, P. 1996. Beyond national boundaries and regional perspectives:contrasting approaches to Spanish colonial archaeology in the Americas. World ArchaeologicalBulletin, 7: 6375.

Wise, K. 1993. Late Intermediate Period architecture of Lukurmata. In Domestic Architecture,Ethnicity, and Complementarity in the South-Central Andes (ed. M. S. Aldenderfer). Iowa City:

University of Iowa Press.

Zucchi, A. 1995. Spanish mortuary practices during the XVIIth to XIXth centuries. In Proceedings

of the XVIth International Congress for Caribbean Archaeology, Vol. 1, pp. 17686.

Zucchi, A. 1997. Tombs and testaments: mortuary practices during the seventeenth to nineteenthcenturies in the Spanish-Venezuelan Catholic tradition. Historical Archaeology, 31: 3141.

Ross W. Jamieson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Archaeology at Simon

Fraser University, in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. He has been conducting

research on the historical archaeology of highland Ecuador for more than ten years, and

has recently begun a project excavating the colonial city of Riobamba, Ecuador, destroyed

by an earthquake in 1797.

372 Ross W. Jamieson