iSimangaliso Wetland Park: ‘The goal is to end the...

Transcript of iSimangaliso Wetland Park: ‘The goal is to end the...

**** 5International Herald Tribune | ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT | Tuesday, December 16, 2008

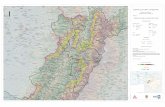

T here are so many different things tosee and do in the iSimangaliso Wet-land Park that few risk going home

disappointed. Centered around Lake St. Lu-cia, the park contains Africa’s largest estu-ary system and its southernmost coralreefs. The variety of natural beauty andabundant wildlife draw about one million vis-itors every year.

Formerly known as the Greater St. LuciaWetland Park (after the name given by Por-tuguese sailors in 1576), it received its newAfrican name in November 2007 — iSi-mangaliso, or ‘‘Miracle.’’ The name is apt.Former South African President NelsonMandela describes it this way: ‘‘The WetlandPark must be the only place on the globewhere the world’s oldest land mammal (therhinoceros) and the world’s biggest terrestri-al mammal (the elephant) share an ecosys-tem with the world’s oldest fish (the coel-acanth) and the world’s biggest marinemammal (the whale).’’

A collection of protected areas, iSi-mangaliso has game reserves, marine re-serves, freshwater reserves, state forestsand most of South Africa’s remainingswamp forests. Numerous organized toursand excursions are geared around almostevery living thing on its land, waters or skies.On land, feline fanciers can take a close look

at Africa’s endangered cheetahs and wild-cats at the African Wildcat Center. Reptileenthusiasts can visit a crocodile and snakecenter. The Web site of Go2Africa, an inde-pendent safari travel service, says: ‘‘Prob-ably the most rewarding experience is aboat trip on the lake, which provides en-counters with waterfowl, hippos, Nile cro-codiles as well as the beautiful fish eagle.’’

Photographers can go on game reservetours and snap buffalo, rhinos, lions and leo-pards. Night drives offer sightings of porcu-pine, aardvark, elephant and antelope.Those who prefer a slower pace might enjoya wilderness walk. There are 196 species ofbutterflies, and bird-watchers can identifymore than 500 species on the hiking trails.iSimangaliso is also a refuge for water birds,and flocks of flamingoes and pelicans canbe found feeding along the coast.

The park’s marine system includes 220kilometers (about 140 miles) of coastlinefacing the Indian Ocean’s warm waters andtropical reefs. Lovers of sea creatures cango whale-watching from June to November,or take a marine mammal tour for dolphinsand sharks from December to May. Thereare even midnight turtle tours. From Novem-ber to January, visitors can watch turtles layeggs — a spectacle available in very fewcountries. Swimmers can snorkel and divein the shallow reef, and there is good fishingat Cape Vidal. Visitors can also explore thewetlands on horseback. Other activities in-clude golf, kayaking, camping and caravan-ning — there is a wide range of recreationalopportunities in the park.

iSimangaliso’s wealth of animal life isdue to its unique diversity of ecosystems. Arare combination of coastline and gamepark, the site includes reefs, lakes, lagoons,thickets and woodlands, dry sand forest,bushland, beaches, grasslands andmarshes. iSimangaliso also boasts Africa’shighest forested sand dunes. Monkeys,squirrels and reptiles live here. The visitorcan enjoy guided tours or stroll alone.

The site is as rich in culture as it is in nat-ural beauty and biodiversity. Visitors can seeZulu and Thonga arts and crafts; receive alesson on local history, traditions, marriagerites and religion; watch tribal dancers andmusicians; and even visit a witch doctor.[

Unesco’s 1972 ConventionConcerning the Protection of theWorld Cultural and Natural Heritagestates that the following shall beconsidered as natural heritage:natural features of physical andbiological formations, or groups offormations, of outstanding universalvalue from the aesthetic orscientific point of view; geologicalformations and delineated areasthat constitute the habitat ofthreatened species of animals andplants of outstanding universalvalue from the point of view ofscience or conservation; and naturalsites or delineated natural areas ofoutstanding universal value fromthe point of view of science,conservation or natural beauty.Visit http://whc.unesco.org

Sports enthusiasts — particularlydivers, who expose their watches tounique shocks and pressures —need a more resistant, andtherefore larger, timepiece. Ideally,divers should also know how longthey’ve been underwater andexactly how deep they are.

Jaeger-LeCoultre’s new line, theMaster Compressor Diving series,offers three models that aredesigned with both professional andnonprofessional divers in mind; theyprovide unique precision, reliabilityand resistance, essential whendiving. The Master CompressorDiving Pro Geographic is larger thanprevious models — 46.3 millimeters(1.8 inches) in diameter — foreasier readability below the waves.Its casing of grade-five titanium iswaterproof down to 300 meters(about 980 feet). A steel membraneinside the case expands and

contracts according to the waterpressure. These movements aretransmitted to a hand in the middleof the dial that shows how deep thediver is, from zero to 80 meters.Since no water can enter themembrane, the gauge is 100-percent reliable.

These new additions make the in-house, hand-decorated Diving ProGeographic the showpiece forJaeger-LeCoultre’s state-of-the-arttechnique. Chief Executive OfficerJérôme Lambert says, ‘‘Jaeger-LeCoultre can produce, from A to Z,inside and out, from case tomovement, anything needed in adiving watch today.’’ This expertiseis built on 175 years ofwatchmaking, Lambert adds.‘‘Generation after generation,’’ hesays, ‘‘we have grown more capableof leading the new dimension ofsports watches.’’

SPOTLIGHT | Rejuvenation and national pride

iSimangaliso Wetland Park: ‘The goal is to end the paradox of poverty amidst the bounty of nature’

The Master Compressor Diving watch: A gift for divers

EXPLORING | Earth, water and culture

From tropical reefs to Africa’s highest forested dunes

What is natural heritage?

Courtship display of the African Jacana.

South Africa’s iSimangaliso Wetland Park,a Unesco World Heritage marine site,

aims to balance conservation anddevelopment, protecting its biodioversity

while empowering the area’shistorically disadvantaged communities

T he story of iSimangaliso Wetland Park— the first South African site to be in-scribed on Unesco’s World Heritage

List — is tied to South Africa’s recentpostdemocratic evolution. It is a tale of reju-venation and national pride. The story be-gins in the park’s coastal dunes. The park isa marine site with terrestrial components,and its dunes, formed over the past 25,000years, rise up to 170 meters (560 feet). Butwhat matters is underneath them: thedunes contain mineralwealth, including titani-um, ilmenite, rutile andzircon.

In the late 1980s andearly ’90s, the site faceda menace from miners. That the dunes heldore was not a new discovery. There is evi-dence of the use and trade of iron tools inthe area from early times. But a mining com-pany wanted to look for minerals in a bigway, and revealed plans to bulldoze thedunes along the eastern shore of Lake St.Lucia, the heart of the park.

Opposition from conservationists and apublic outcry over what was understood tobe a looming ecological disaster promptedhalf-a-million citizens — including then-Pres-ident Nelson Mandela — to sign a no-miningpetition. This led in 1996 to a governmentban on industrial development in the area. Italso led to the nomination of the park as a

World Heritage site. But the battle was iSi-mangaliso’s defining moment. Thrust intothe spotlight, it became emblematic of thenew nation and the focus of an emphasis onstrategic nature tourism as a spur to eco-nomic growth in the country as a whole.

After outlawing mining in the park, thegovernment went further, outlining in 1999 astrategy of development initiatives for theentire region. Together with the govern-ments of neighboring Swaziland and

Mozambique, it begana drive to promote em-ployment in the area,with iSimangaliso asthe core. Focusing ontourism and agricul-

ture, initiatives included the creation of4,500 temporary jobs a year for local com-munity members. Today, initiatives supportlocal entrepreneurs; build skills in tourism,conservation and hospitality; train chefs andtour guides; provide opportunities for localcontractors; and put people to work on con-struction and maintenance of park roads.Specialized initiatives, such as craft and cul-tural performance programs, target womenand young people.

Guy Debonnet, chief of Unesco’s SpecialProjects Unit, notes: ‘‘Instead of going forlarge-scale economic development basedon resource extraction, the government de-cided to stimulate a more sustainable local

development, directly benefiting the localcommunities.’’ These communities areamong the nation’s poorest. World Heritagestatus, authorities believed, would help pro-duce momentum to generate opportunitiesfor them. So great was this belief that SouthAfrica became one of only two countries(Australia is the other) to incorporate theWorld Heritage Convention into national law.The World Heritage Convention Act of 1999ensures that the country complies with thecommitment it made to Unesco when pro-posing iSimangaliso as a World Heritagesite. It created a special Wetland Park Au-thority to manage iSimangaliso and — per-haps its most important function — over-see the betterment of the social andeconomic conditions of local people.

The World Heritage Convention Act givesthe iSimangaliso Wetland Park Authority amandate to deliver tangible benefits to com-munities living in and around the park. An-drew Zaloumis, chief executive officer of thepark authority, says: ‘‘Importantly, this lawlaid the foundation for a new model for pro-tected area management in South Africa, asit recognized that conservation without ac-knowledging the needs of the poor peopleliving in and around the park would ulti-mately erode its conservation status.’’

‘‘Developing to conserve’’ is iSimangal-iso’s motto, and its objective is to safeguardits ecological wealth while empowering its

historically disadvantaged communities.Adds Zaloumis: ‘‘The purpose of the devel-opment initiatives was simple but ambitious— to end the paradox of poverty amidst thebounty of nature. The park is a people'spark, balancing biodiversity protection andecosystems rehabilitation with a commit-ment to social equity and economic devel-opment.’’ The law amounts to a proud na-tional pledge for the park’s conservation.Unesco leaves countries free to make goodon their obligations to World Heritage asthey see fit, but considers the South Africanstatute an example of best practice, oftenciting it to other World Heritage Conventionsignatories.

The new model, combining a new nation-al consciousness and World Heritagestatus, has helped deal with other park is-sues. At its time of inscription in 1999, someof iSimangaliso’s landscapes had been

planted with introduced species, such as eu-calyptus. Park authorities began a drive toremove foreign flora; today the park is freeof commercial plantations. Seven thousandhectares (17,300 acres) of pine and euca-lyptus have been removed from its Easternand Western Shores area, and many zoneshave recovered their natural vegetation. Thepark is also restocking animals that havedisappeared. Three years ago, the cheetahwas reintroduced, and the park authorityhas brought back many endemic species, in-cluding elephant, buffalo, black rhino, wilddog and hyena. World Heritage status hasplayed a role here. Says Zaloumis: ‘‘The gov-ernment invested considerable resources inthe World Heritage site, due to its status andits potential to deliver economic benefits.Restoration and rehabilitation of the sitewas an important part of the overall devel-opment and conservation strategy.’’[

The fight against miningwas iSimangaliso’sdefining moment

Male hippos fighting.

NIG

EL

DE

NN

IS

NIG

EL

DE

NN

IS

�eNeM Mfj �emjN Zi �e\j�joNeMj iZO IemjZNò e[MjOIejGNp[m \ZOj e[iZO\pMeZ[ Z[�ZO]m ¯jOeMphj \pOe[j NeMjNÔGGGïefMïnZ\îMemjNZiMe\j

�emjN Zi Me\jÔ e�e\p[hp]eNZ�jM]p[m �pO^ mem [ZM e[IZ]Ij Mfj OjQZOMe[h ZOjmeMZOep] mjQpOM\j[MN Zi Mfj ®¯�ï ®M eN Mfj NeFMf Zi p NjOejN Z[ �[jNnZ’N �ZO]m¯jOeMphj \pOe[j NeMjNï �fj [jFM e[NMp]]\j[Mò Z[ Mfj �fp]j �p[nMJpOE Zi µ]�e@npe[Zò Ge]] oj QJo]eNfjm Z[ «p[ï çßï �fj NjOejN eN p QpOM[jONfeQ p\Z[h«pjhjOñ¨jºZJ]MOjò �[jNnZ’N �ZO]m ¯jOeMphj ºj[MOj p[m Mfj ®[MjO[pMeZ[p]¯jOp]m �OeoJ[jï �jFM oE «¤�¯�½ «½§�¤¨ï ³ZO e[iZO\pMeZ[ Z[ Mfj ®¯�½mIjOMeNe[h �JQQ]j\j[MN QOZhOp\Ô GGGïefMe[iZïnZ\îQphjNîpmIjOMeNe[h

![THE ISIMANGALISO WETLAND PARK AUTHORITY REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL … · 2020. 11. 20. · REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL [RFP] FOR MANAGEMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF ISIMANGALISO ENTERPRISE DEVELOPMENT](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/60915aec1e479075fe631a90/the-isimangaliso-wetland-park-authority-request-for-proposal-2020-11-20-request.jpg)