Investingin BRAZIL · BrasilAgro, a subsidiary of Cre-sud of Argentina; Radar Proprie-dades...

Transcript of Investingin BRAZIL · BrasilAgro, a subsidiary of Cre-sud of Argentina; Radar Proprie-dades...

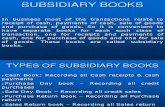

BRAZILInvesting inFINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Thursday May 17 2012

www.ft.com/reports/investing-brazil-2012 | twitter.com/ftreports

T here is an old saying inBrazil – para inglês ver,or “for the English tosee”. It essentially

means to do something for showand the joke is that this idiom –which dates back to the 19thcentury when the countryofficially banned slavery just toplease imperial Britain but con-tinued the trade in secret – isdefunct.

In 2011, Brazil surpassed theUnited Kingdom as the world’ssixth-largest economy so it nolonger matters what the Englishthink (if it ever did), or so thejoke goes.

This milestone was one morestep in what Jean-Marc Etlin,chief executive officer of ItaúBBA Investment Bank, calls“the tail-end of a long process ofnormalisation” of Brazil’s oncecrisis-wracked economy.

This remarkable period ofreform, which began in 1994with the introduction of thepresent currency, the real, andblossomed in the past decadewhen the country enjoyed aperiod of remarkable prosperity,has put it on the world map asan investment destination.

“When investors have savingsto be invested on a global basis,they are saying there is no harmhaving some of it exposed toBrazil. That has been a bigchange,” says Mr Etlin from hisheadquarters in Faria Lima, theSão Paulo avenue that is hometo Brazil’s investment banks.

In the second decade of the21st century there seems to be

no limit to what Brazil mightachieve next. Already an agri-cultural power, the country hasbecome an important destina-tion for global consumer compa-nies keen to tap its growingmiddle class. With the FifaWorld Cup and the OlympicGames taking place in the nextfour years, infrastructure com-panies are gathering. The inter-national oil industry is also

shifting to Rio de Janeiro to jointhe rush to tap giant offshorereserves of crude.

But while Brazil, the mostwesternised of the so-called“Brics”, which also include Rus-sia, India and China, remains afavourite among investors, thenext few years promise to bemore challenging.

With the world economy slow-ing, many argue Brazil needs a

fresh spark to keep it growing.Policy makers are under pres-sure to consider a second gener-ation of reforms in areas suchas taxation, infrastructure andeducation to make the countryglobally competitive.

“It looks good relative to thepast, but the opportunities areeven greater,” says Loy Pires,country manager of Brazil forthe International Finance Cor-

poration, the private sectorinvestment arm of the WorldBank. “If they were to tacklesome of these structural issuesthe number of investors wouldquadruple.”

Fuelled by expansive govern-ment lending, the economypeaked in 2010, when it grew at7.5 per cent, the fastest in dec-ades. Investors flocked to thecountry, eager to invest in this

Latin American giant whoserate of growth resembled that ofan Asian tiger.

The excitement turned tohype. Entrepreneurs listed theircompanies en masse and mem-bers of the new middle class,many of whom were usingcredit for the first time, boughtfridges and televisions, encour-aged by the president at thetime, the charismatic metal-worker-turned-statesman LuizInácio Lula da Silva. Propertyprices more than doubled.

Arminio Fraga, a former cen-tral bank governor and founderof Gávea Investimentos, anasset management company,says: “While Brazil is growingmore than 4 per cent on aver-age, which is good, the bottomhalf of our population is grow-ing faster. So the story aboutthe consumer base is for real.”

But in 2011 reality threatenedto disrupt the party, as the gov-ernment stimulus spurred infla-tion, which eventually exceededthe central bank’s target of 4.5per cent plus or minus 2 per-centage points.

In August of that year signsemerged of a big slowdown inindustry. After tightening mone-tary policy sharply the centralbank suddenly began cuttingrates.

By the end of the year theeconomy had virtually stalled,clocking growth for the full 12months of 2.7 per cent, but infact contracting slightly in thethird quarter compared with theprevious three months.

Since then the economy hasbeen running at two speeds.

The first is for domestic indus-try, which has been shrinkingon the back of a strongerreal against the dollar and alack of competitiveness againstcheaper imports.

Inside this issueManaging land paysdividendsFarming isadvancingwithoutdestroyingthe naturalenvironmentPage 2

Growth to continueA wealth of naturalresources, a governmentinvesting seriously ininfrastructure and apopulation of consumersmean the party is far fromover, writes Richard LapperPage 2

Property The rapid growthof the middle classes andthe expansion of themortgage market are two ofthe main factors behind thereal estate boom Page 3

Oil & GasBG’sportfolio ofcovetedexplorationblocksneeds hugeinvestment– at least

$42bn to develop its 6bnbarrels of oil reservesPage 4

Manufacturing Eventhough the auto sector isone of the country’s largestindustries, expansion bycarmakers is a on acollision course withpoliticians’ protectionistpolicies Page 4

Wealth managementRising incomes mean thebusiness is booming as

the country hasbecome oneof the world’stop producersof millionairesPage 4

Spark needed to ignite economyAlthough growth hasslowed, the country isstill a good investmentbut stability requireslong-term reform,reports Joseph Leahy

Continued on Page 3

Generating business: a worker at the largest hydropower manufacturing plant in the world – being built at Taubate, in São Paulo state Getty

2 ★ FINANCIAL TIMES THURSDAY MAY 17 2012

Investing in Brazil

A t an FT conference onsustainable agriculturein Brazil held inLondon at the end of

March, you could almost hearthe hackles rising around thehall as John Clarke, EuropeanCommission internationalaffairs director for agriculture,explained his concerns aboutthe social and environmentalimpact of Brazilian farming.

He noted there had beenprogress on issues such as childlabour and slave labour butthey still needed attention. Ille-gal logging continued to destroyBrazil’s rainforests. And, ofcourse, the country’s giant com-modity crops such as soya andsugarcane were displacingranchers and pushing them intothe Amazon basin.

Few things are more exasper-ating for farmers and officials inBrazil – where vast areas ofnative ecosystems still survivein spite of generations ofdestruction – than being lec-tured at by Europeans whoseancestors long since choppeddown almost all their primevalforests. No amount of persua-sion, it seems, will convince out-siders that the majority of Bra-zilian agriculture takes placetens, hundreds and even thou-sands of kilometres from theAmazon forest.

The figures most often pro-duced to support the Braziliancase concern land use and pro-ductivity. In the 1990-91 harvestyear, there were 9.7m hectaresof land under cultivation inBrazil producing 15.4m tonnesof grains. In 2010-11, land undercultivation was two and a halftimes bigger, at 24.2m hectares.Production, meanwhile, hadgrown almost fivefold, to 72.2mtonnes of grains.

Productivity had almost dou-bled, from 1.58 tonnes a hectareto 3 tonnes a hectare, accordingto government statistics.

What is more, the farm minis-try will tell you, the majority ofnew land under cultivation hadbeen taken from “degraded”land – often, areas that hadbeen cleared by early settlers,used for low-density ranchinguntil the soil’s nutrients were

gone, and then abandoned. Offi-cials insist there is ample landof this type available for freshcultivation without touching astick of the Amazon forest.

Nevertheless, sensitivities arehigh and illegal logging andranching are far from eradi-cated, which means that manyinvestors in Brazilian agribusi-ness want to be doubly suretheir produce will reach domes-tic and export markets withoutthe risk of contributing to envi-ronmental damage.

This has been a spur to betterstandards of land managementand social responsibility. How-ever, new investment in Brazil-

ian farming also has to offer anattractive return.

Over the past generation,farmers have been migratingfrom southern Brazil – wherethe deep-red topsoil is amongthe most naturally fertile in theworld – to what were the barrenlands of central Brazil south ofthe Amazon basin.

By the use of lime and othernutrients, farmers have madethis, too, some of the most pro-ductive farmland in the world.

In the western state of MatoGrosso, where farms cover tensof thousands of hectares ofmostly flat land criss-crossed bywaterways, land prices are now

among the highest in thecountry.

Recent investment has turnedto Brazil’s newest agriculturalfrontier in the north-easternstates of Maranhão, Piauí,Tocantins and Bahia.

Native vegetation here ismostly savannah-like cerrado –woodland that is tall and densearound rivers and sparse andscrubby in between. Environ-mentalists involved in preserv-ing the cerrado say Brazil is oncourse to achieve its aim ofleaving at least 35 per cent ofthe natural land cover intact.

In western Bahia, around thetown of Luis Eduardo Magal-

hães – little more than a fillingstation a decade ago and now athriving municipality – landprices have rocketed.

About five years ago landcould be bought for aboutR$2,000 to R$3,000 a hectare(about $1,000 to $1,500). Today,uncultivated land there sells forR$5,000 to R$6,000 and landalready under cultivation fortwice that amount.

“In the past five years, [theincrease in land prices] hasbecome almost a self-fulfillingprophecy,” says André Pessôa, afarming consultant. “It hascome true because a lot of peo-ple believe the same thing. But

it’s not a bubble. It has beenwell leveraged. The priceincludes the belief that this areawill consolidate as a big pro-ducer [of soya and cotton] andthat better logistics will arrive.”

One of the pioneer investorsin this part of Brazil is SLCAgrícola, one of the few agribus-iness companies listed on theSão Paulo stock exchange. Itsbusiness model – to buydegraded land and make it pro-ductive – has made it one of thebiggest landowners in Brazil.

A recent arrival is AgrifirmaBrasil Agropecuária (ABA),created last September in a jointventure between BRZ Investi-mentos, a Brazilian privateequity group, and Genagro, aUK land development companypreviously known as AgrifirmaBrazil.

A survey of agribusiness inBahia published in February byBrazil Confidential – an FTresearch and analysis service –identified investments in Bahia,in addition to those by SLC andABA, by Calyx Agro, an invest-ment vehicle launched in 2007by Louis Dreyfus Commodities;Los Grobo Ceagro, an Argen-tine-Brazilian joint venture thatrecently sold a 20 per cent staketo Mitsubishi of Japan for $46m;BrasilAgro, a subsidiary of Cre-sud of Argentina; Radar Proprie-dades Agricolas, a subsidiary ofCosan, the Brazilian sugar andethanol group; and Multigrain,acquired by Mitsui of Japan lastyear.

Julio Bestani, chief executiveof ABA, told Brazil Confidential:“We see three types of return:operational returns from farm-ing, land appreciation over time,and the value that can be addedto land by transforming it andmaking it productive.”

Mr Pessôa notes that inves-tors are counting not only onproductivity gains but also onimproved logistics.

Farmers in western Bahia willtell you they are among themost efficient in the world, butthat they lose out to competitorsin Argentina and the USbecause of the high cost of get-ting their produce to exportmarkets.

The region’s farmers shouldget a boost from a railway lineunder construction to link west-ern Bahia to the port of Ilhéus.

There is no guarantee of lowerprices, however. Other farmersin Brazil recently served by raillinks have found that operatorsprice their services to competewith costly road transport butnot undercut it.

Better land management pays dividendsAgricultureFarming is expandingwithout destroying theenvironment, writesJonathan Wheatley

Brazil is on courseto achieve its aimof leaving at least35 per cent of naturalland cover intact

Rich harvest: land prices in the western state of Mato Grosso, where farms cover tens of thousands of hectares, are now among the highest in the country Reuters

New York and Londontrading rooms do not havemany people with anythinggood to say about Brazil.

Flavour of the month onfinancial markets not so longago, the country is nowdismissed, even disdained.

“Most investors think theparty is over,” the head ofone equity sales desk toldme last week, before goingon to list negatives,including dependence on rawmaterials and China,overvalued shares andseveral messy episodes ofgovernment interference.

But talk to theinternational companiesploughing record amounts ofcapital into the country andyou get a very differentimpression.

True, they say, the webs ofred tape surroundingbusiness are as annoying asever and Brazil will struggleto grow at the 7.5 per centrate achieved in 2010.

But there areoverwhelming strategicpositives. First, there is therange and scale of Brazil’scomparative advantages innatural resources. It is theonly one of the so-calledBrics (the group of countriesthat includes China, India,South Africa and Russia)that is self-sufficient inwater, energy and food.

Its comparative advantageas a producer of soya andiron ore is the pivot aroundwhich its relationship withChina, its biggest tradingpartner, revolves.

Its offshore “pre-salt” oilreserves stand out as one ofthe most attractive frontiersfor the oil industry, withreserves conservativelyestimated at 50bn barrels.

Second, after two decadesor more of neglect, thegovernment is finallybeginning to invest ininfrastructure, developingthe roads, ports and airportsthat should help fosterregional integration andreduce business costs.

External pressures linkedto the 2014 World Cup and2016 Olympic Games willconcentrate official minds,accelerating advances thatmight otherwise progress ata painfully slow pace.

Third, the enthusiasm ofBrazilians to consume isturning into a considerablemacroeconomic advantage,sucking in direct investment($66.7bn in 2011 and aforecast £56.7bn this year)helping cover a current

account deficit andcompensate for still very lowdomestic savings rates.

In spite of the slowdown inthe economy towards theend of last year sales ofeverything, from razorblades, chocolate, shampooand lipstick to luxurywatches, perfumes, carsand televisions, are growingat near double-digitpercentage rates or evenhigher.

In some sectors – such ascosmetics or personal care –where, for cultural reasons,

Brazilians spend a muchhigher proportion of incomethan North Americans orEuropeans, the local marketis poised to become thebiggest in the world.

Regular on-the-groundsurveys on these markets byBrazil Confidential, aresearch organisation set upby the Financial Times inFebruary 2011, confirm thisenthusiasm.

In our most recent report,on shampoo, toothpaste andother personal care items,we found that people on lowincomes were especially keento spend on more upmarketbrands.

Our survey of 1,000Brazilians in late Marchshowed prestige brands suchas TREsemmé, a shampoomanufactured by Unilever,and Oral B and Sensodyne,toothpastes made by Procter& Gamble and GSKrespectively, are flying offthe shelves (see box, right).

In case studies conductedin Diadema, a lower-classsuburb to the south of SãoPaulo, we found womenwhose households hadincome of only about R$1,000($555) a month wereprepared to spend up toR$130 ($72) a month onbeauty and personal careproducts.

Interviewees oftenpreferred to stretch theirbudgets to buy qualitybranded items.

On the markets, investorsworry the boom in creditand job creation that fuelledthis rise in consumptionbetween 2005 and 2010 is

running out of steam. Lastyear, indeed, there was sometalk of a Brazilian subprimecrisis.

It is certainly true that –because bank lending ratesare shockingly high – someborrowers are overstretched,paying significant amountsof their income in servicingtheir debts.

But several trends areeasing the burden. Interestrates have been cut –overnight rates have fallenby 300 basis points since lastAugust – and banks areunder intense pressure topass the benefits toconsumers.

Unemployment is at recordlows but, as thousands ofpeople continue to move outof the informal sector, thenumber of job applicants iscontinuing to rise.

Likewise, hundreds ofthousands of informal

traders, shop owners,hairdressers and other one-person businesses are joiningthe formal economy.

Sebrae, a small andmedium-sized businessadvisory group, has said that4,500 such operations werebecoming fully legal eachday.

That will mean suchbusinesses will now have topay tax, but it will alsomake it easier for theirowners to claim socialbenefits, open bank accountsand obtain loans.

Contrary to theconventional market view,but like the direct investors,we reckon that Brazil’sconsumer-driven growth isset to continue for sometime.

The writer is the principal ofBrazil Confidential, the FT’sBrazil research service

Cosmetics Products gel with lower income workers

For Cosmo Barros, a 37-year-oldbartender who works in the down-at-heel neighbourhood of Brás in centralSão Paulo, finding ways to save moneyfor his family of six, which survives onR$2,000 ($1,038) a month, is vital,writes Luke McLeod-Roberts.“We can’t be more than five minutes

in the shower. To save water andelectricity, I have to turn the showeron, get wet, then turn it off, soapmyself, then turn it on again,” he says.Despite this seemingly frugal attitude

Mr Barros still likes to splash out onthe occasional luxury. He once spentR$300 on Carolina Herrera 212 eau decologne and aftershave balm, forexample, after managing to persuadethe shop owner, who is a friend, togive him a discount.Mr Barros’s love of international

brands – and his use of socialnetworks to acquire such products –is typical of Brazil’s growing andincreasingly self-confident lower middleclass.Marlene Torreno, a 62-year-old

retired nurse, who is waiting to haveher hair done at a beauty salon inDiadema in the south of the city, saysshe always uses L’Oréal Paris Imédiahair dye.“It’s the most expensive, about R$32

a bottle, but R$5 bottles, such asMaxtone, are not worth it; they dry thehair a lot,” she says.Ms Torreno has a pension of

R$1,200 a month, but neverthelessspends more than 10 per cent of herincome on hair dye and other beautyproducts.According to on-the-ground

interviews in São Paulo and an onlinesurvey with 1,000 consumersnationwide, carried out by the FinancialTimes’ Brazil research service BrazilConfidential, spending this kind ofproportion of monthly wages onbeauty and personal care products isthe norm among lower-incomeconsumers, who value both brandimage and quality.Unilever’s shampoo and conditioner

line TREsemmé, sold in the kind ofblack plastic bottles associated withexpensive salons, is a case in point.TREsemmé had an estimated market

share of just 0.4 per cent following itsBrazilian launch in the second half oflast year, but nearly 10 per cent of the500 women interviewed online inMarch had bought a bottle in the firstquarter of this 2012 and 17 per centplanned to do so in the next threemonths.Toothpaste is also a sector where

consumers are buying upmarket.Although Colgate is the market leader,our survey showed that up to a fifth ofrespondents planned to buy the much

more expensive Oral-B and Sensodynebrands over the next three months,percentages that exceed their 2011respective market shares.Part of the reason for this

attachment to more expensive brandsamong lower income groups is thesense of aspiration that accompaniesrising income levels.Falling unemployment and

government income distributionprogrammes have seen 40m join theranks of the so-called “C class”, asocioeconomic band that denotesthose with monthly household incomesof a little over R$1,000 a month tojust over R$4,000. And it is thisgrouping that has become a big targetof foreign direct investment in theretail and consumer sectors.But this patronage of trendy brands

is also related to the particularlyBrazilian love of looking and feelinggood. There is no better example forhow ingrained this tendency is in localculture than the candour with whichconsumers speak about their desire forplastic surgery, in contrast to thesense of discretion associated with itin Britain.In the city of Diadema, 41-year-old

administrative assistant Celia Alvessays she is planning on having breastimplants inserted this year.“It costs R$10,000, plus the hospital

costs, but my husband will pay for it.Women are luxury items. If a manwants to have a woman, he has topay,” she says.Pensioner Ms Torreno would also

like to go under the knife but needs tosave up first.She says: “There’s a clinic here and

I have friends who have been there,the aesthetician has a very goodreputation. I would like to save moneyto get my eyes lifted.”

Luke McLeod-Roberts is a São Paulo-based senior researcher for FT BrazilConfidential

Consumptionand resourcesare central todevelopment

Smile: low-income Brazilians are especially keen to spend on upmarket personal care goods

Brazil

Source: BCB, IBGE, Brazil Confidential

GDP, retail sales and lending (%)

-5

0

5

10

15

2000 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

Credit growth (lending to individuals, % of GDP)Retail sales growth (annual % change)GDP growth (annual % change)

Brazil is the onlyBric group memberthat is self-sufficientin water, energyand food

Personal grooming in Diadema

Richard LapperBRAZIL CONFIDENTIAL

FINANCIAL TIMES THURSDAY MAY 17 2012 ★ 3

Investing in Brazil

Industrial production inMarch this year was down3.9 per cent on a year ear-lier. However, the marketfor services and consump-tion is buoyant, thanks topay increases and recordlow unemployment.

“Activity data have beenmixed in Brazil, as firmingdemand contrasts withstruggling manufacturing,”Itaú BBA said in a researchnote.

The government’s re-sponse has been to criticiseadvanced economies, whoseloose monetary policy hasunleashed what DilmaRousseff, the president,calls a “tsunami” of liquid-ity into global markets.

This has artificiallystrengthened the real andmade local industry uncom-petitive, the governmentsays.

Ms Rousseff’s governmentis seeking to use the globalslowdown to reduce interestrates, which are among theworld’s highest for a largeeconomy.

In a breakthrough move,the government haschanged the terms on popu-lar poupança savingsaccounts, whose generousguaranteed tax-free returnswere blamed for putting afloor under rates.

The central bank ispoised to lower its bench-mark Selic rate in late May,from 9 to 8.5 per cent,which would be a 15-yearlow.

Still, investment flowsremain solid, if more selec-tive than in 2010. Brazildrew record foreign directinvestment last year at$66.7bn and is expected toreceive a healthy $56.7bn in2012.

Private equity groupsattracted record funds forthe country last year andbond market inflows werealso strong, although theyhave since softened on gov-ernment efforts to deterspeculative investors.

In April, the equity mar-ket hosted its first signifi-

cant initial public offeringsince last July, that of BTGPactual, the homegrownLatin American investmentbank. But the $2bn listingwas not expected to spark awholesale revival of equityofferings amid adverse glo-bal risk appetite for emerg-ing-market stocks.

While Brazil’s investmentstory is solid, it needssupport. While efforts toreduce rates are laudable,many economists and busi-nessmen are calling formore fundamental reformsto improve infrastructureand education, reduce taxa-tion and lift productivity soindustry can compete with-out heavy-handed govern-ment protection.

Luciano Coutinho, presi-dent of Brazil’s biggestlong-term lender, thenational development bank,

BNDES, says: “There isonly one way to combineprice stability, higher prof-its and higher wages, whichis higher sustainable pro-ductivity gains.” He addsthat productivity has beenrising at only a sluggish1.8-1.9 per cent a year.

In the end, economistssay, the onus is on the gov-ernment, which spends toomuch too unproductively,leaving little room in theeconomy for the increasedsavings needed for invest-ment.

Mr Etlin of Itaú BBAsays: “The main point Iwould like to see as a Bra-zilian is to have a reallyprofound discussion onwhat is needed to create theconditions for this countryto be really competitiveover the long run.

“Otherwise, if we do notaddress it, that is some-thing that will lead us to hitthe wall at some stage.”

Spark needed toignite economyContinued from Page 1

Sustainableproductivitymustincrease,says LucianoCoutinho

In Rio de Janeiro’s big-gest slums – or favelas– many of which wererecently invaded by

paramilitary police to driveout gangs of drugtraffickers, there is onething everyone complainsabout: the high rents.

In Santa Marta, forinstance, it now costs aboutR$400-R$500 ($207-$259) amonth to rent a smallmakeshift bedsit half wayup the mountainside, resi-dents say.

The price is even higherfurther down near theentrance to the favela,where electricity cables aremore plentiful and there isless chance of your homeslipping in a mudslide.

“It’s getting crazy,” saysRicardo de Souza, a 31-year-old salesman who was bornin Santa Marta. “Even justfinding somewhere that isvacant is difficult.”

It not just in the favelasthat real estate prices havesoared. Over the 12 monthsto April, the average priceper square metre of residen-tial real estate rose 21.8 percent, according to the Fiperesearch foundation, whichtracks prices every monthin the country’s biggestseven cities.

The price per squaremetre for one-bedroom

apartments rose more than30 per cent over the year toR$8,141.

The rapid growth of themiddle classes and theexpansion of the country’smortgage market are two ofthe main factors behind thereal estate boom.

After nearly 20 years ofeconomic stability, theproperty market has alsobecome a hot target fordomestic and foreign inves-tors.

For some, however, theboom is no more than abubble. Analysts at CapitalEconomics published areport last month titled“Why Brazil’s propertyboom looks like a bubble”,arguing the market is over-valued by as much as 50 percent.

“House prices haveincreased out of all propor-tion to the rise in householdincomes and the spread ofmortgage finance,” wroteNeil Shearing at the consul-tancy. “As a result, Brazil-ian housing now looksexpensive relative to bothincomes and rents, as wellas property in other [emerg-ing markets]”.

Some have even dedicatedwebsites to the bubble the-ory such as bolhaimobili-aria.com (literally “proper-tybubble.com”), setting outto prove that Brazil is fac-ing a US-style housing mar-ket crash.

However, the majority ofanalysts and professionalsbelieve that the country’shousing market has little incommon with those ofcountries such as the US orSpain.

“I don’t believe there is abubble,” says FábioMaceira, head of the Brazil-ian unit of Jones LangLaSalle, the property con-sultancy.

He adds: “The mortgagemarket is very small here.Yes, it’s growing, but it’sstill very small.”

Mortgage lending iscurrently only 5.2 per centof gross domestic productaccording to the country’scentral bank, comparedwith about 64 per cent inSpain, 77 per cent in the USand 85 per cent in the UK.

With 60 per cent of thenation’s population forecastto be in the middle classesby 2018, demand is likely toremain strong in both resi-dential and commercialproperty, says Mr Maceira.

“Brazil’s north-easternregion is an excellent mar-ket – in fact, anywherewhere you have an emerg-ing population with grow-ing disposable income,” hesays.

“They have more to spendon food, appliances, andmore consumption means

more shops and distributioncentres.”

Efforts by policy makersto bring down Brazil’s tradi-tionally high benchmarkinterest rate, which at 9 percent is now just 25 basispoints off a 15-year low, arealso expected to boost realestate values.

“I see Brazil as clearly inthe early stages of a cyclein real estate for a couple ofreasons,” says ArminioFraga, a former Braziliancentral bank president.

“One, there is demand,there is income growth, par-ticularly at the bottom, andthen there is also a slow butvisible downward trend ininterest rates, which is veryimportant for real estatebecause you can get financ-ing at a decent cost.”

Rather than being a bub-ble about to burst, the prop-erty market has recentlyshown signs of slowing.

For example, while theaverage price for a squaremetre of Brazilian residen-tial real estate rose 1.2 percent in April from theprevious month, last April

the market registered amonthly variation of 2.7 percent, according to Fipe.

Construction companieshave particularly struggledduring this slowdown, rush-ing to shift away from theirambitious growth plans at atime of soaring costs.

Shares in Gafisa, one ofthe biggest housebuilders,have more than halved invalue over the past year.

Mr Maceira also believesthe commercial real estatemarket may also be begin-ning to stabilise, withrental prices even nearingtheir peak as new officespace becomes available.

“A lot of new product willcome to the market, mainlyoffice space, calming themarket in both São Pauloand Rio. In two years, weshould see a rise of about 50per cent in supply,” MrMaceira says.

“Currently, we have alandlord market, where thelandlord can push up rentalprices because of the lack ofspace. But in two years, weshould finally see a morestable market.”

Real estatebecomestarget forinvestorsPropertyA rapidly growingmiddle class hasboosted prices, saysSamantha Pearson

Rooms with a view: the slums of Santa Marta, where rents have risen despite the poor standards of housing Getty

ContributorsJoseph LeahyBrazil Bureau Chief

Samantha PearsonBrazil Correspondent

John ReedMotor IndustryCorrespondent

Richard LapperPrincipal, Brazil Confidential

Luke Macleod RobertsSenior Researcher, BrazilConfidential

Adam JezardCommissioning Editor

Steven BirdDesigner

For commercial informationregarding Latin Americacontact:John Moncure+1 212 642 [email protected] orAlejandra Mejia+1 212 641 [email protected]

4 ★ FINANCIAL TIMES THURSDAY MAY 17 2012

Investing in Brazil

When asked what he mostloves about Brazil, theanswer from Nelson Silva,head of BG’s operations inthe country, is very simple:BM-S-9, BM-S-10, BM-S-11,BM-S-50, BM-S-52.

The series of codes,known as the “big five”, arethe names of some of themost coveted oil and gasexploration blocks inBrazil’s Santos basin. Bur-ied deep beneath the oceanfloor off the south-east

coast, these reserves are setto produce nearly as muchas the entire UK North Seawithin a decade, helpingcatapult Brazil into theranks of the world’s top fiveoil producers.

For Mr Silva, they arealso crucial to the com-pany’s future.

The UK-based oil and gasgroup is the only foreigncompany to hold stakes inall five blocks – an offshoreportfolio that promises toturn BG into the secondbiggest oil and gas group inBrazil after state-run Petro-bras, but also one that willrequire potentially cripplinglevels of investment.

The company has indi-cated it would need toinvest at least $42bn indeveloping its 6bn barrels ofoil reserves, more than the

entire gross domestic prod-uct of neighbouring Para-guay. Some analysts fearBG has become overexposedto the Brazilian market,with assets in the countryworth about $45bn.

BG’s position is largelythe result of it being one ofthe first foreign groups totake an interest in thecountry, entering in 1994 tohelp build a $2bn gas pipe-line to Bolivia.

At that time, the countrywas an economic basketcase in the eyes of theworld, having changed itscurrency five times in 10years and having sufferedinflation rates of more than2,000 per cent.

But following almost twodecades of economic stabil-ity and the discovery of thecountry’s vast so-called

“pre-salt” oil in 2007, Brazilhas now attracted at least36 foreign companies to itsupstream market, accordingto Ernst & Young.

Mr Silva says: “In 1994BG made a strategic deci-sion to invest in the coun-try and then, after the dis-covery of the Lula field,Brazil became even moreattractive,” .

The Lula field, whichranked as the biggestdiscovery in the Americasfor three decades and holdsan estimated 8bn barrels,lies in the BM-S-11 block,where BG owns 25 per centof the concession.

BG also has a 30 per centstake in the BM-S-9 blockthat holds the Carioca field,25 per cent of BM-S-10, 20per cent of BM-S-50 and 40per cent of BM-S-52, which

it operated during theexploratory phase.

However, the companyis facing increasing compe-tition in the Brazilian mar-ket, which is expected toaccount for more than a

third of the group’s totalvolumes by 2020.

Sinopec, the Chinese oiland petrochemical group,has been moving particu-larly fast, buying 30 percent of the Brazilian assetsof Portugal’s Galp Energia

for $5.2bn last year. Thestate-owned group hadalready paid $7.1bn for a 40per cent stake in the Brazil-ian assets of Repsol, theSpanish group, in 2010.

In the neighbouringCampos basin, Norway’sStatoil not only holds 60 percent of the BM-C-7 blockthat contains the Peregrinofield but it is also operatorof the area.

However, while BG facesgrowing competition fromnewcomers in the industry,its biggest challenge isdeveloping the reserves italready has.

Mr Silva explains: “Weare entering a new phase,where growth will increasea lot and so, naturally,investments will also accel-erate from now on.”

After investing just over

$5bn in Brazil since 1994,BG’s chief executive hasindicated the company willpour more than $42bn intoits Brazilian operationsover the next decade, say-ing it would cost about $7 abarrel to develop the com-pany’s 6bn barrels ofreserves.

Mr Silva told the Finan-cial Times last month thatthe group also plans tospend an extra $2bn onresearch and developmentin an attempt to address awidespread shortage oftrained professionals in theindustry.

Part of BG’s projectedinvestments is likely tocome from the proceeds of aglobal asset sale, which thecompany announced lastmonth would include thesale of a 60 per cent stake in

Brazil’s largest gas distribu-tor Comgás that it boughtin 1999.

Analysts at banks such asNomura have also advisedBG to sell part of its inter-est in its oil blocks to allowthe company to invest morein other regions, but thecompany has so far shownno signs of backing downfrom its core business inthe country.

“BG announced in Febru-ary this year that it will sellsome assets, worth in totalabout $5bn,” says Mr Silva.“But the company is veryfirmly established here inBrazil. We are very happywith the relationship withPetrobras, the government,BNDES [Brazil’s statebank].

“Our focus has been oninvesting more and more.”

BG has five big reasons why country is key to its futureOil & GasGroup is sitting onvaluable discoveriesbut developmentcosts are huge, saysSamantha Pearson

If boom and bust are the recur-ring themes in Brazil’s recenteconomic history, carmakersdoing business there have been

having a typically manic time.Nearly all the big automakers have

been expanding plants or buildingnew ones to take advantage of risingnumbers of drivers, reflectingresource-led economic growth and theexpansion of the middle class.

But now they face slowing car salesand a volatile regulatory climate.

Sales fell by 11 per cent in April, asa slower economy and a creditsqueeze deterred consumers.

Brazil’s government, in protection-ist mood because of the stronger real,has been jiggling the levers of tradeand tax policy to persuade automak-ers to build locally rather thanimport. The changes have unsettledcarmakers, some of which, includingBMW, are revisiting their businessplans.

Ian Robertson, the Munich car-maker’s sales boss, told the FinancialTimes in April that the company hadbeen “delayed” in its decision onwhether and where to build whatwould be South America’s first green-field premium car plant.

“We are looking to build a plant inBrazil, but I don’t know what size it

should be. If I had done my exercisebefore December, it would have beenX, but now it’s X-minus.”

The auto sector is one of Brazil’slargest industries, accounting for 6 to8 per cent of gross domestic productand about 25 per cent of manufactur-ing. Like other nations, Brazil valuesthe sector because it generates skilledemployment and jobs at suppliers.

However, as government policymakers seek to shape a globalised sec-tor to the needs of a national agenda,analysts and auto making executivessay Brazil must tread carefully or riskforgoing new jobs.

Just two years ago, Brazil’s carindustry was firmly in “boom” mode,as producers clamoured to enter amarket on course to overtake Japanas the world’s third-largest by 2011.

At the time just four big manufac-turers held dominant positions – Fiat,Volkswagen, General Motors, andFord Motor – and commanded healthyprofit margins to match.

Since then South Korea’s Hyundai,Japan’s Nissan, Fiat, Toyota, andChina’s Chery Automobile and JAChave all begun building plants. Ford,VW and PSA Peugeot Citroën areexpanding existing ones.

IHS Automotive, an industry ana-lyst, projects that in 2011-16 Brazil willsee about $25bn of investments at car-makers alone, not including suppliers.

“Any existing player is definitelypumping money in and you have thenew players as well,” says Guido Vil-dozo, IHS’s Latin America expert.

Last September the governmentraised the taxes on imported cars by30 percentage points, to between 37and 55 per cent, in response to surg-

ing imports. The rise, which tookeffect in December, hit producers suchas Hyundai and BMW that do not yetproduce locally, while leaving carsmade in Mexico and Mercosur eligibleto enter the country duty-free.

Car imports from Mexico soared asbuyers switched to cheaper vehicles,prompting Brasília to impose a three-year quota regime, rising from $1.4bnthis year to $1.6bn in the third year.

The move angered Mexico andobstructed the plans of some carmak-ers who do business in both countries.

Nissan, Mexico’s largest carmaker –which is building a R$2.6bn plant inRio de Janeiro – said the clampdownon Mexican-built cars could damageits dealer network in Brazil.

Speaking to the FT in March, JoseMunoz, president of Nissan Mexicana,said the quotas could also backfire onBrazilian suppliers of “flex-fuel” sys-tems, which Nissan had planned toimport into Mexico to fit into carsbuilt there for export to Brazil.

Even longstanding investors havehad a tough time in a slowing market.Since 2011, GM and Ford have bothreplaced regional managing directorsafter reporting financial losses intheir South American units.

Grace Lieblein, president of GM inBrazil says it is “one of the most com-petitive markets I have seen”. Sheadds: “The cost structure here is high

and it’s increasing, whether you aretalking about labour, logistics ormaterial. This is a tough place to dobusiness from a cost perspective.”

To keep automakers investing – andincreasing the amount of regionalcontent they put in their cars – Brazilis fashioning a policy for the sector,dubbed “Brasil Maior” (Bigger Brazil).

Described as an “automotive incen-tive plan”, it is couched in the lan-guage of carrots rather than sticks.

Longstanding carmakers and newinvestors will be induced to spendmore on research and developmentand innovation in the country, inexchange for incentives such as man-ufacturing tax breaks.

Analysts say that, if drawncorrectly, the policy could help Bra-zil’s domestic-focused car industryraise its game and begin exportingagain. “With all the installed capacityin Brazil, they do need to go back toexporting,” says IHS’s Mr Vildozo.“They need to bring the industry upto par in order to do that.

Governmenterects barriersto automakers’drive for growthManufacturingExpansion by carmakerscollides with effects ofpoliticians’ protectionistpolicies says John Reed

Gearing up: a worker checks an engine at a Chevrolet assembly line in the General Motors do Brasil plant in São José dos Compas Bloomberg

Wealth management Rising incomes mean the business is booming

“Oh how adooooorable! It’sso good to do a little bit ofshopping, isn’t it!,”screeches Val Marchiori asshe steps inside a private jetfor sale in São Paulo with aglass of champagne in hand.“For me, it’s the same

thing as buying a new top,you know.”The scene is from

Mulheres Ricas (RichWomen) – Brazil’s firstreality television show tofollow the lives of thecountry’s superwealthy.From spontaneous

shopping sprees in Paris tobathing in mineral water, theextravagances of the fivefemale millionaires featuredin the recently airedprogramme offer a glimpse– albeit exaggerated – intoan emerging class.While rising income among

the country’s poorest hascaptured the attention ofinvestors around the world,Brazil’s upper classes havealso been enjoying their ownboom, as they reap therewards of a growingdomestic economy.The so-called A and B

classes – those earningmore than R$7,475($3,873) a month – areset to more than doubleby 2014 on the 2003figure, to more than 29mpeople. Brazil has alsobecome one of thetop producersof millionaires,creating onaverage 22 a

day in 2010, while thecountry’s billionaires are nowovertaking their rivals indeveloped countries.Eike Batista, the Rio de

Janeiro-based tycoon, iscurrently ranked by Forbesas the world’s seventhwealthiest person with afortune of about $30bn.This growing legion of

super-rich is a welcomeboost to luxury brands fromFerrari to Veuve Clicquot,but has also allowed thecountry’s wealthmanagement industry toflourish.Data from Brazil’s

Financial and CapitalMarkets Association(ANBIMA) show that therewas R$434.4bn undermanagement in thecountry’s private bankingsector in December 2011, anincrease of 21.6 per cent onthe previous year.The most popular options

are investment funds, whichat the end of last year

accounted for 43per cent of

privatebankingassets,and fixedincome,whichmade up36.7 percent.

While growth in thenumber of new privatebanking clients slowed in2011, to 5.9 per cent, theaverage value of assets heldby each person increasedfrom R$7.5m to R$8.6m.Maria Eugênia López,

director of Banco SantanderBrasil’s private banking unit,says: “The private bankingsector continues to grow.The Brazilian economy isrelatively stable comparedwith Europe and the US, andwe continue to see activecapital markets.“Because the Brazilian

economy is performing well,you also have moredividends paid bycompanies, which naturallymeans these resources endup in the pockets ofinvestors,” she adds.This new wave of

prosperity is not justconfined to São Paulo andRio de Janeiro. For example,in Rio Grande do Sul,Brazil’s most southerly statenext to the Uruguayanborder, most wealthyfamilies used to make theirfortunes in agriculture.But as more factories are

established in the region tomeet growing demand forconsumer goods, as well asto produce machinery forthe offshore oil and gasindustry, a secondgeneration of millionaires

is emerging.Silas Caldana is

director of OsloPatrimômio, a wealthmanagement businessin the state that looksafter clients with morethan R$50m inassets.

He comments: “There is alot of repressed demand inthe south, where manypeople have huge amountsof money sitting in retailbanks and don’t know whatto do with it.”However, Brazil’s current

monetary easing cycle couldslow the growth of theprivate banking industry,given that a big chunk ofassets are kept in Brazil’shigh-yielding fixed incomemarket.Economists expect the

central bank to cut thebenchmark Selic interestrate again later this monthto 8.5 per cent, bringing itdown to the lowest level inmore than 15 years.President Dilma Rousseff

this month also paved theway for further cuts byreducing the guaranteedreturn on tax-free savingsaccounts, which hadthreatened to lure investorsaway from government andcompany bonds if the Selicfell any lower.While this should come as

good news for Brazil’spoorest, who typically buyeverything from televisionsto socks on credit, thecountry’s wealthy may soonfind that the days of easyreturns on their investmentsare coming to an end.Santander’s Ms López

says: “Last year, we had amaximum interest rate of12.5 per cent, but now wehave something in theregion of 9 per cent so the[private banking] market willgrow, but not at the rate itdid last year”.

Samantha Pearson

TheRio-basedtycoonEike Batista

‘We are enteringa phase wheregrowth will increaseand so investmentswill also accelerate’