Interlingual Interference among Bilinguals

Transcript of Interlingual Interference among Bilinguals

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

The Impact of Interlingual Interference on Bilingual Brain: Slowdown in Word Processing in Hebrew as

a Result of Auditory Similarity to Russian

Research Seminar on Visual Imagery Course (10547)

Student Name: Igor Greenblat Student ID Number: 308896638 Directed By: Dr. Avner Caspi

1

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Contents

ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................4

INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................................5

Attention ........................................................................................................................................................................ 5

Focused and Divided Attention .................................................................................................................................... 5

Task Automatization, Spatial orientation and Stroop Color-Word Task ................................................................ 6

Stroop Color-Word Test and its linkage to Attention flexibility ............................................................................... 6

Stroop Effect – General Research Review (McLeod, 1991)....................................................................................... 7

Emotional Stroop Effect (ESE) – a dispute regarding the nature of phenomena mechanism. Is ESE actually a Stroop task? The "Absence of Interference" argument by Daniel Algom (2005).................................................... 8

The Role of Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) in emotional and cognitive processing – a physiological support to the distinction between the Classic and Emotional Stroop Effects ....................................................................... 9

Bilingual Lexical Organization, Dependency/Interdependency between L1 and L2............................................. 10

Linking Bilinguality and Attention............................................................................................................................ 11

The Bilingual brain - Processing Levels and Cross-Lingual Interference.............................................................. 11

Taboo words as ESE stimuli....................................................................................................................................... 12

Emotional expressiveness of bilinguals in L1 and L2: Processing figurative language by bilinguals .................. 13

Dual Coding as an aggravating factor in Stroop task .............................................................................................. 13

Rationale of the current study.................................................................................................................................... 14

Independent Variables ................................................................................................................................................ 15

Dependent variable ..................................................................................................................................................... 15

Hypotheses ................................................................................................................................................................... 15

METHOD.......................................................................................................................................................17

Participants.................................................................................................................................................................. 17

Procedure ..................................................................................................................................................................... 17

Materials ...................................................................................................................................................................... 18

2

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

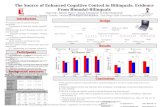

RESULTS .....................................................................................................................................................19

Data Preliminary Analysis.......................................................................................................................................... 19

ANOVA ........................................................................................................................................................................ 19

Descriptive Data .......................................................................................................................................................... 19

DISCUSSION................................................................................................................................................21

Interpreting Findings.................................................................................................................................................. 21

Revising the Phenomenon of Interlingual Interference ........................................................................................... 21

Drawbacks and Artifacts of the Current Study; Suggestions for the Future Research ........................................ 23

REFERENCES..............................................................................................................................................27

APPENDIXES ...............................................................................................................................................34

Appendix I: Research group classification............................................................................................................... 34

Appendix II: Test stimuli sample (1x1 scaled) .......................................................................................................... 34

Appendix III: Task words list classification to groups............................................................................................. 35

Appendix IV: ANOVA Summary Table ................................................................................................................... 37

Appendix V: Group Means ........................................................................................................................................ 37

Appendix VI: Tukey HSD Test Values...................................................................................................................... 37

Appendix VII: Eta-Squared Data .............................................................................................................................. 37

3

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Abstract

The impact of Reverse Interlingual Interference Effect (RI – word processing inhibition that

occurs during translation from L2 to L1) on Russian-Hebrew bilingual's performance in

Emotional Stroop task was examined. The difference in performance between bilinguals and

monolinguals was tested with exactly the same sets of stimuli; when the stimuli was neutral

(no auditory coherency between the word in Hebrew and any word in Russian lexicon) the

difference in time responses was hypothesized to be a result of language "utilization

seniority". Moreover, it was argued, that additionally to standard Stroop interference,

bilingual participants' color naming is inhibited by unaware subliminal activation of semantic

networks in Russian language (whether dominant or not) and to between-language

competition due to auditory alikeness between the Stroop stimuli in Hebrew and words from

Russian lexicon, rather than being an artifact of stimulus selection or experimental design.

The hypotheses of the present study derive from theories and ascertainments in a field of

cognitive psychology, such as Disturbed Feature Model (De Groot, 1992), Dual-Coding

theory (Paivio, 1971), taboo words emotional impact on word processing (Siegrist, 1995),

second language processing interference (Francis, 1999) and others. The findings suggest that

auditory interference rooted in the similarity of the stimuli in L1 with obscene, concrete or

abstract word is significantly incapable of activating alternative stimuli processing route and

thus interfering with the cognitive processes involved in color-naming task. However, the

observation of group means allows a certain level of speculation regarding the revealed

tendencies.

4

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Introduction

Attention

The world we live in is full of sensory stimuli. If human brain had to process all the input

entering the central nervous system, it probably would have collapsed under such an

unbearable cognitive burden. Human brain data processing capabilities are much wider than

animal's (Evans et al., 2005), although not infinite. In every given moment the cerebrum

absorbs enormous amounts of data: sunlight, clock ticking, room temperature level and so on;

different signals are processed differently due to various signal features as sharpness and

intensity (Kutas & Federmeier, 1998). It is likely that monotonic serene chirp of a cricket

will not interrupt our sleep thanks to habituation of our auditory system; in contrary a loud

police siren noise will arouse us immediately (Condon & Weinberger, 1991). Is the way we

respond to certain stimulus intentional and the decision to respond or to ignore various

ambient occurrences is always taken consciously? More likely, the responses are extracted by

our brain autonomously, without wasting our precious cognitive resources. Apparently, we

owe our proper functioning to very complicated network of cognitive schemes "wise" enough

to decide which of the concurrent input signals deserve high-level processing above the

others. The cognitive mechanism responsible for input data filtering is Attention. Neisser

(1974) defines it as "The assignation of the mechanisms of analysis to a limited part of the

perceptual field".

Focused and Divided Attention

William James (1890) writes, "…Attention is taking possession by the mind, in clear and

vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of

thought". The quote focuses in on the necessity of humans to take possession of only one

object with their mind despite the several options present. The limited capacity of the human

information processing system requires individuals to select the information they deem most

important to attend to. Usually we focus and divide our limited attention resources according

to the number of tasks we have to perform and the importance of those tasks (Kahneman,

1973; Navon & Gopher, 1979; Wickens, 1984). It is much easier to divide the attention

voluntary between reading and chewing gum than between driving a car and speaking on a

cell phone; in the last case we direct most of the attention resources to the speaking task and

avert the attention from driving, which might cause an accident (Strayer et al., 2003). The

5

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

"neglected" tasks are sometimes performed automatically, without squandering attention

resources. Automatization of a cognitive task requires experiencing; avoiding the route flags

on the way down might be a routine task for an experienced skier, but not for an amateur.

Attention can be attracted involuntarily, as if a lamp in a dark room suddenly lights up or

voluntary, as if we want to observe "what will happen next", glazing at the traffic light. An

"attention-drawing" stimulus is more salient than others; among those unique attributes are

content subjective significance, such as hearing your own name (the "cocktail party effect",

Cherry, 1953), background/foreground separation (white flower in a green field, Spieth,

1954; Webster, 1954) or emotional distinctiveness (snake in the grass; Anderson, 2005).

Recent cognitive theories (Bunting & Cowans, 2005; Gopher, Greenshpan & Armoni, 1996)

perceive the attention as a flexible resource, allocated accordingly to task requirements; we

are able to focus the attention on relevant stimulus or divide it to various stimuli, if necessary.

Task Automatization, Spatial orientation and Stroop Color-Word Task

When a certain behavior is performed frequently and does not require intentional attention

resources, it becomes automatic or "procedural" (Anderson, 1983). We perform automatic

behaviors quickly, precisely and effortlessly, often involuntary, "it just happens". In order to

explore the modus operandi of procedural behavior, psychological researchers simulate

situations, where intentional and automatic responses conflict, the interference allows them to

examine the latent features of the automatic behavior by testing their influence on observable

behaviors. Such an influence perfectly outlined by Stroop Color-Word Test. In visual

orientation, preattentive processes provide a spatial mapping of physical locations and allow

us to target attention resources and to distinct the target from the background noise (Lamers

& Roelofs, 2007). However, selecting a spatial location does not separate the target and the

distractor in the Stroop task, since the word meaning and the color are spatially integrated or

concentrated in a common part of a spatial field. Therefore, when attending the ink color of a

Stroop-word stimulus, the meaning of a word receives attention resources as well and

"sneaks" into our cognitive system.

Stroop Color-Word Test and its linkage to Attention flexibility

Stroop Effect, a "part of the limited golden fund of psychodiagnostic tools", as Emil Siska

(2002) defines it, firstly presented in an article "Studies of Interference Serial Verbal

6

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Reactions", published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology in 1935. The effect is

named after its inventor, John Ridley Stroop, who discovered it working on his PhD thesis in

George Peabody College (today part of Vanderbilt University) and introduced the results to

professional practice. When implementing the classic form of the Stroop color-word test, the

subject is initially required to read words representing names of some basic colors, and

quickly to name the ink color of these words, disregarding the actual meaning of the words.

The phenomenon of interference, characterizing all the existing variations of Stroop test is

caused by the competing phonological route of the graphical representation of the word

(Tanenhaus, Flanihan and Seidenberg, 1980) and the actual color of the ink when the later is

incongruent with the meaning of a word; this process is not intentional and unavoidable. The

conflicting tasks involve focal attention to the critical element of the task which must be

selected in competition with a dominant, semantic (phonologic) element. However, word

naming is not affected by the color of the ink (MacLeod, 1991) due to the prevalence of

phonology over physical characteristics of the stimuli.

In order to perform in Stroop Task, the participant should obtain some flexibility implicating

attention resources; neuroimaging of adults who suffer from Attention Deficit Disorder

(ADD), unlike the normal controls show no activation of the Anterior Cingulated area of the

cortex, involved in regulation of cognitive activity (Bush et al., 1998). Instead, they show

greater activity on incompatible trials in the Anterior Insula (Bush et al., 1999). As was

suggested in the study of word association, the Insula represents a more automatic pathway

than the Anterior Cingulate, ADD patients having difficulties to dissipate attention efficiently

and let it be attracted subliminally, instead of targeting intentionally.

Stroop Effect – General Research Review (McLeod, 1991)

In his monumental taxonomy "Half a Century of Research in Stroop Effect, an Integrative

Review", Colin M. MacLeod (1991) covered the history of the attempt to combine the word

and color stimuli in a potentially conflicting situation. Since the original experiment by J. R.

Stroop, the number of published articles on issue exceeded 700, probably the investigators

were appealed by the simplicity and the reliability of the experiment. Various versions of the

task appeared, including the picture-word interference task (Dyer, 1973), auditory task

(Hamers, 1973), sorting and matching task (Tesse & Happ, 1964).

7

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Emotional Stroop Effect (ESE) – a dispute regarding the nature of phenomena mechanism. Is

ESE actually a Stroop task? The "Absence of Interference" argument by Daniel Algom

(2005)

It has been shown that emotion is an important element in directing attention in the working

memory processes (Mather et al., 1995). In "Emotional Stroop Paradigm" participants are

asked to name the color of a printed words partly loaded with emotional connotation.

Apparently, naming a color of an unpleasant word such as "grief", "fear" or "death" takes

more time comparatively to neutral words (Williams, Mathews & MacLeod, 1996; Sharma &

McKenna, 2001; Whalen et al., 1998). The "Emotional Stroop Paradigm" is a very popular

tool not solely in the cognitive research area, but in clinical-psychopathological area as well

(investigating eating disorders - Dobson & Dozois, 2001; alcohol dependency – Flannery et

al., 2007; PTSD patients – Emilien et al., 2000; schizophrenia - Henik et al., 2002; and also

Constatntine, McNally & Hornig, 2001; Kindt & Brosschot, 1997; Lavy & van der Hout,

1993; Watts, McKenna, Sharrock & Tresize, 1986). The classic approach to the explanation

of the phenomenon is that additional attention resources required while processing

emotionally negative stimuli since the usual color naming response interferes with the

subliminal processing of the emotional stimuli (Freyd, 1996; Williams, Mathews & McLeod,

1996). However, not all the researchers agree that ESE is an attention (or lack of attention)

phenomenon. A group of psychologists from Tel-Aviv university claims, that emotionally

loaded stimuli is processed slower because of the activation of "general-purpose defense

mechanism" that responds to a threat by "temporarily slowing down or even freezing all the

ongoing activity" (Lev, 2002; Algom, Ben David & Levy, 2003). Since a major slowdown

for emotional words has been found in studies of lexical decision and reading aloud as well,

the researchers reject the claim that ESE caused by cognitive overload or incapability of the

selective attention mechanism; furthermore, Algom even rejects the argument that ESE is a

subcategory of Stroop tests array. He claims that ESE lacks the essential features of a Stroop

task – the Item-Specific Interference and Congruent Conditions. For the color Stroop the

interference can be calculated at the level of the item and not at the level of the whole list, as

it is in the ESE. Moreover, there's no congruent condition in ESE. The semantic conflict (in

the incongruent condition) and agreement (in congruent condition) that forms the basis of the

color Stroop effect is absent from the ESE phenomenon. In this sense, the Emotional Stroop

task is not really a Stroop task at all.

8

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

A group of University of California researchers (Mackay et al., 2004) reject the classic

"attention-related" perception as well, defining the described inhibition phenomena as an

"Inhibitory mechanism preventing awareness of taboo words" and explaining it by

"enhancement of the explicit memory during encoding".

Klauer (2003) proposes an additional explanation to ESE phenomenon – "Automatic

Vigilance", an unaware evolutional readiness to give more attention to processing of

threatening stimuli. Automatic vigilance occurs when a negatively valence target stimulus (an

image of a COCKROACH) is categorized more accurately when it is preceded by a

threatening prime stimulus (e.g., the word DISEASE) than a neutral prime stimulus

(Hermans, DeHouwer, & Eelen, 2001). Similarly to a reflex, it happens without our

awareness or effort, and runs to completion without conscious monitoring. The effects may

be far-reaching, especially when automatic vigilance impacts on cognitive resources such as

attention and memory. However, the Automatic Vigilance Theory supporters can't explain the

inhibition in ESE when there's no priming condition; ESE researches show extended response

times even when the participant processes the emotional stimuli in the first time, without any

preliminary priming.

All recent hypotheses concentrate on mechanisms that differ from the classic theory: the

evolutionary coping explanation (Algom et al. version), memory phenomena (in Mackay et

al. research) and Automatic Vigilance version (Klauer et al.) considered to be in the focus of

ESE, and not the attention.

The Role of Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) in emotional and cognitive processing – a

physiological support to the distinction between the Classic and Emotional Stroop Effects

The dissociation between the classical Stroop task and ESE was proven empirically in both

lab experiments (Algom, Chajut & Lev, 2004) and clinical experience of abused Post-

Traumatic Stress Disorder patients, who's symptoms were dramatically facilitated during ESE

performing and remained almost unaffected during the classical Stroop (Bremner et al.,

2004). Recent theoretical and experimental work (Botvinick at al., 2001; Drevets and Raichle

1998, Bush et al, 2000) has shown that Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) may be divided into

two parts, each half exclusively responsible for different type of mental processing. When

strong emotions are involved in a Stroop test or any other task, the dorsal area of ACC is less

active than at rest, while cognitive conflict tasks, such as the classic Stroop task suppress

9

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

activity in the ventral ACC. fMRI evidence from a variety of tasks indicates that two parts

might be mutually inhibitory – cognitive tasks knocking down the emotional activity in ACC

and vice versa. According to the presented findings, emotional words amplify mental activity

in the emotional "half" of the ACC and depress the processing in the second "half" which

controls the cognitive processing. Research of the emotional Stroop involving both control

(George et al., 1994; Whalen et al., 1998) and clinical (Rauch et al., 1994; Rauch et al., 1996)

population have shown high levels of activation in both ventral and dorsal ACC, when

traditional Stroop studies (Bush et al., 1998; Carter, Mintun & Cohen, 1995) have shown

activities in caudal part of ACC. The described neuropsychological dissociation is leading to

the conclusion that two tasks (the classical Stroop and ESE) are distinct since the anatomical

modules being activated during the tasks are different and even mutually inhibitory.

On the other hand, the notion that emotion and cognition are functionally interdependent is

supported at both the behavioral and neuroanatomical level. When faced with stimuli or

situations that elicit negative affect (ESE, for example), people rely on regulatory processes

mainly involved in attention (Rothbart, Posner & Hershey, 1995). PET and MRI studies have

linked both the traditional and emotional Stroop to a network of neural systems critical for

the expression and self-regulation of emotion (van Honk et al., 2000; West & Alain, 2000).

Those observations do not contradict the previous statement concerning the distinction of the

Classic and the Emotional Stroop tasks, but only emphasize the complexity of the human

mind and the interdependence of its processes.

Bilingual Lexical Organization, Dependency/Interdependency between L1 and L2

Over fifty percents of world population speaks at least two languages. Posing unique

challenges to the human brain, multilingualism requires simultaneous activation of two or

more sets of rules, sometimes very different ones. A bilingual individual, in order to escape

the curse of Babel, has to juggle between two languages performing code switching (a rapid

switching from one language to another, Dehaene, 1999); avoiding the cross-talk apparently

requires operating of sophisticated mechanisms of segregation and coordination (Dehaene,

1999). In one of the physiological researches (Price at al., 1999) scientists used Positron

Emission Tomography techniques (PET) in order to clarify the "modus operandi" of a

bilingual brain. Unsurprisingly, switching between two or more languages and translating

from one language to another requires activation of additional language brain areas

10

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

additionally to the "classical" ones (such as Broca's Area). Seems, that bilingual brain, at least

among highly proficient bilinguals, addresses the problems of lexical data processing by

operating with a unique plasticity; the pattern of bilingual cerebral activation is different for

each language and some brain regions are activated in one language but not in other (Perani

et al., 1998).

Do bilinguals use two languages independently, alternating between them, or keep both

languages activated simultaneously and process every stimulus in two parallel lexical routes?

This question is investigated widely in psychocognitive research, the interaction of lexical

processing between the first (L1) and the second languages (L2) argued to be independent or

interdependent. A traditional language switch hypotheses (Gerard & Scarborough, 1989;

MacNamara & Kushnir, 1971) assume independent selective activation and deactivation of

the languages, while parallel activation theories (Grainger & Dijkstra, 1992; Chen & Ho,

1986; Cummins, 2000) challenge the traditional ones, claiming that robust competition exist

between and within language effects in both languages.

Linking Bilinguality and Attention

As one item is selected to be attended to, the individual must inhibit the competing items.

Inhibition is therefore a critical feature of attentional control. Both deal with the concept that

many tasks require fixed attention to certain aspects of the problem while ignoring the other.

Inhibition is used daily, for example, when choosing groceries in the supermarket. A variety

of milk cartons are available and one must inhibit the motor act of ignoring the undesired

cartons on the shelf so that the chosen carton can be simply picked. Bilinguals are constantly

required to use this skill when speaking and listening to one language and ignoring the other.

The Bilingual brain - Processing Levels and Cross-Lingual Interference

How do speakers of more than one language represent and process the words in each

language? Kroll and Stewart (1994) claim that word forms associated with the dominant and

non-dominant languages are "located" in two independent "word banks", the Revised

Hierarchical Model (RHM) proposes distinct lexical word form representations in each

language, but a common conceptual system. A similar "Bilingual Production" model

presented by international group of researchers (Costa, Colome & Caramazza, 2000; Illes et

al., 1999) claims that a common single semantic representation level for both L1 and L2 co-

11

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

exists in parallel with distinct lexical representations for each language. Some studies have

reported evidence suggesting that both alternatives are possible (Champagnol, 1975; Dyer,

1971; Durgunoglu & Roediger III, 1987; Kolers, 1963; Preston & Lambert, 1969), implying

that the issue of single versus dual memory storage in bilinguals may be a matter of

interpretation.

How do two distinct lexicons co-exist and interact in bilingual brain? La Heij et al. (1996)

claim, that the semantic context has a more powerful effect on the processing in the backward

direction than in the forward direction (L2-L1 versus L1-L2 translation). Ambiguous words

or words with multiple translations are processed differently and more slowly comparatively

to concrete words. De Groot (1992) explains in Disturbed Feature Model that concrete words

share the same representational distribution across languages, they are more likely to overlap

in meaning and therefore being translated more quickly. In this model, semantic concepts are

not represented by single nodes, but by a bundle of feature nodes. Each word activates a

pattern of features in both languages. Most of the researchers share the agreement that

processing within the language always interferes with the processing between the languages.

When a bilingual participant tries to name the color of the word in L2, the Stroop interference

(top-down processes superiority) causes a subliminal processing of the word, even though the

later is not required and slowing down the response time (Francis, 1999).

Taboo words as ESE stimuli

Since obscene words are taboo in the modern society, they appear as "emotionally loaded"

stimuli and therefore fit the definition of the Emotional Stroop task stimuli. Word forms can

directly activate emotions: when people name the color of randomly intermixed taboo and

neutral words, color naming times are longer for taboo than for neutral words (Siegrist,

1995); this suggestion presents a theoretical base for the hypothesis of the current research.

For monolingual speakers, recall and recognition tests are influenced similarly by

emotionality, with emotion words showing an advantage compared to neutral words (Rubin

& Friendly, 1986). Jay (2000) defines obscene words as "super emotion" in terms of the

diversity and strength of associated contexts and emotions. When scientists measured the

electrodermal activity (EDA) of participants exposed to swear and neutral words (Bowels &

Pleydell-Pearce, 2004), autonomic response to swear words was indubitably longer than to

neutral stimuli. Taboo words activate the amygdala (LaBar & Phelps, 1998), known to be a

12

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

key subcortical structure for threat-detection. MacKay et al. (2002) argued that the superiority

of recall for taboo words occurs because emotional reactions during encoding facilitate

binding of the taboo word to its context.

Emotional expressiveness of bilinguals in L1 and L2: Processing figurative language by

bilinguals

Diverse studies support the idea that the first language is bilingual's choice for expressing

emotions (Javier, Barroso & Munos, 2003; Sechrst, Flores & Arellano, 1968; Anooshian &

Hertel, 1994; Bloom & Beckwith, 1989). If the first language is linked to emotional

expressiveness, the second language may be the language of emotional indifference: people

discuss taboo issues (Bong & Lai, 1986), tend to reveal more secrets (Gonzales & Reigosa,

1976) and report less anxiety to obscene and taboo words (Gonzales & Reigosa, 1976) in L2.

There are few studies focusing on the figurative aspect of language comprehension and

production (Francis, 1996; Souto Silva, 2000), but even fewer studies covered the obscene

language aspects. However, an existing wide research base of the emotional aspect of

bilingual cognition allows us to predict certain response patterns of bilingual participants to

taboo (obscene) stimuli in L1 or auditory similar stimuli in L2 which activates the obscene

network in L1. I hypothesize, that neutral word in L2 auditory similar to obscene language

stimuli (swear is a part of a figurative language) in L1 will interfere the usual processing of

the word in L2 among bilinguals. Actually, any auditory similarity between the target word in

L2 and any word in L1 should interfere the usual processing in L2 as was hypothesized

before, but additionally to the auditory similarity the obscene word as a taboo-emotionally-

loaded stimuli might cause an additional inhibition in mental processing.

Dual Coding as an aggravating factor in Stroop task

Cognition according to Dual-Coding Theory (DCT, proposed by Allan Paivio in 1971 and

developed in 1986) involves the activity of two different subsystems; a verbal system

specialized for dealing with language and imagery system, dedicated to pictorial processing.

Both systems are involved in language processing and the interplay between them depends on

the developmental level and on the nature of the stimuli – difficult to image abstract words

will be processed mainly verbally and concrete words both verbally and visually. A concrete

word that can be imagined as a pictorial representation of its semantic meaning is easier to

13

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

process; the coding into Long Term Memory is performed on the double basis - verbal and

visual. Memory footprints of concrete words are therefore stronger comparatively to abstract

words, the coding and the decoding (recollection) of the word is faster and easier. The

expected additive memory benefit of dual code has been confirmed in numerous experiments

(Paivio, 1975; Paivio & Lambert, 1981).

In 1986 Paivio presented the Bilingual Dual-Coding Theory (BDCT). The BDCT proposes an

architecture in which a common imagery system is connected to two verbal systems which

are linked to each other via associative connections. The interconnection between the three

systems explains the interdependent functional behavior. Keeping in mind the reinforced

coding of the "imaginable" word, I hypothesize that Bilinguals will process Stroop Task

words in L2 (Hebrew) auditory similar to concrete words in L1 (Russian) longer than the

abstract words, the color naming response will be inhibited because of the subliminal

processing of the pictorial representation (an image) additionally to concept processing of the

printed word. For example, a word "soroka" ("crow" in Russian), according to Dual-Coding

Theory, will activate both pictorial and verbal networks while processing the auditory similar

Hebrew word "sruka" (the Hebrew alphabet allows both words' similar typing), participant's

imagination will draw a picture of a craw, additionally to the verbal stimuli. However,

processing the Hebrew word "ot" ("from" in Russian) will activate the verbal network of the

coherent word solely, since abstract words are impossible to visualize. Words in Hebrew with

an auditory similarity to concrete words in Russian will not have any effect on Monolingual

Hebrew speakers since no semantic networks will be activated.

Rationale of the current study

Bilinguals seem always to activate L1 while processing words, but the results about whether

bilinguals activate L2 when they are attending to L1 are conflicting (Marian, Spivey, &

Hirsch, 2003; Xue et al., 2004). In order to cause bilinguals parallel activation of both

languages while processing a stimuli word in Stroop color task, the presented words should

be unique (attention-drawing, based on Cocktail party effect, Cherry, 1953). Three "unique"

auditory connections of the presented stimuli were chosen for the current work; it was either

concrete, obscene (taboo) or abstract.

Each of sixty participants, partly Israeli-born without any knowledge in Russian language,

partly bilingual immigrants whose primary language (L1) is Russian and secondary (L2)

14

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Hebrew or vice versa (L1- Hebrew and L2-Russian) was asked to name as quickly and

precisely as possible the color of printed words in Hebrew presented on the screen of

notebook computer. The response times were recorded using Direct RT software and

processed. Hebrew words selected for the task were classified into four groups: neutral (no

particular auditory linkage to any word in Russian), auditory coherent to abstract, concrete

and obscene words in Russian. None of the auditory Hebrew-Russian similar word categories

was predicted to affect the response times of monolingual participants above the average

response time for a neutral stimuli.

Independent Variables

Group type – three values were defined for this variable: Monolingual, Bilingual (speaking

both Hebrew and Russian) with Hebrew as a dominant language and Russian-dominant

Bilingual.

Stroop Stimuli type or Reverse Interference type – there were four conditions: the neutral

condition – no auditory overlap between the Hebrew stimuli and any word in Russian, an

auditory coherence with a abstract word (Top-Down Interference only), an auditory

coherence with a concrete word (Top-Down Interference + Dual Coding impact) and an

auditory coherence with a obscene word (Top-Down Interference + Emotional taboo-related

effect) in Russian.

Dependent variable

Response Time – since it is usually impossible to monitor cognitive processes directly, a

collateral way of dependent variable monitoring – the "footprints inquiry" will be utilized.

Using response times measurement as an indicator to the complexity of a cognitive process is

a usual technique in the field of cognitive psychology. It's more than reasonable to assume,

that longer response time represents more complex mental process.

Hypotheses

The current research consists of 3x4 array; three groups (one control group of monolinguals

and two test groups comprised of bilinguals with Hebrew or Russian as dominant language)

participated in an experiment, while three lexical interference conditions were applied (no

15

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

interference means that the Hebrew stimuli is neutral, that is to say that it's not auditory

coherent with any word in Russian, abstract, concrete, or obscene stimuli). For the

monolingual group the response times (color naming times) are not expected to vary

accordingly to auditory similarity of any kind between task words in Hebrew (their native

language. It was hypothesized, that the performance of both test groups will be influenced by

interference caused by auditory coherence of the processed word in Hebrew to abstract,

concrete or obscene word in Russian language. Since the coherency to concrete words

supposedly is influenced by Dual Coding and the color naming is inhibited by Reverse

Interference, both semantically and visually, the color naming slowdown in this case is

hypothesized to be stronger (longer response times) relatively to abstract words condition. It

was also expected, that moderate slowdown among Hebrew-Dominant Bilinguals in all the

experimental conditions comparatively to Russian-Dominant Bilinguals will occur; they lack

the theoretical-semantic aspects of language acquisition and the knowledge of obscene

lexicon. It is logical to assume that Russian-dominant bilingual subjects were quite

comfortable speaking Hebrew for most of the day, and going home and conversing with their

parents, grandparents, and siblings in Russian. However, their results are predicted to be

slower than Monolinguals' since their knowledge of Russian language is beyond zero.

16

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Method

Participants

The sample was comprised of sixty adult male and female participants (ages ranged from 22

to 46, with mean of 27.8 and SD of 7.6) drawn from heterogenic population – peers

(university students and friends) and colleagues. The bilingual participants were children of

immigrants from the former Soviet Union, either Israeli-born or born in USSR, all of them

acquired their Hebrew skills while being in Israel; fluent in Hebrew and at least at the basic

level in Russian (based upon self-report). The initial identification for Hebrew-dominant

bilinguals was "Russian-speakers born in Israel", however due to inability to spotter the

relevant population the criterion was "softened" : the participants who immigrated to Israel

before the age of six or reported "Poor" Russian level were classified as "Bilinguals with

Hebrew as a dominant language"; those who immigrated after the age of six and reported at

least a "Reasonable" proficiency level were classified as "Bilinguals with Russian as a

dominant language". Israeli-born participants were classified as "Monolinguals", unless

identified their Russian speaking proficiency level as "Reasonable" (two participants).

The control group was comprised of Israeli-born participants, fluent in Hebrew and

completely non-proficient in Russian.

Procedure

All the participants were asked (in Hebrew) if they wish to participate in an anonymous

research voluntary, those who agreed provided the following information:

1. Number of years speaking Russian solely before obtaining any knowledge in Hebrew

(if applicable).

2. Age when immigrated to Israel (if applicable).

3. Speaking proficiency level in Russian: Poor, Reasonable or Good (if applicable).

Upon completion of the questionnaire the participants were tested using the Emotional Stroop

Task. Subjects were tested individually in similar conditions, during their leisure time (no

pressure of any kind was observed). The participants were instructed to ignore the meaning of

the words and to respond as quickly and precisely as possible to the color of the presented

stimuli by pressing either the red button located in the left side of notepad keyboard or the

green button located in the right part, in accordance with the color of the presented word. The

17

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

participants were told that each word would be presented by the software on a black screen

and will be replaced by another word upon pressing one of the buttons. The pattern was held

constant – thirty four words were presented accordingly to pre-set list in a constant order;

words of all categories were mixed (the list is presented in "Appendix III" section). The

participants performed a "pilot" adjustment test comprised of five stimuli words before the

actual task; the results of the pilot test were not processed. Three categories contained what

was hypothesized as "potentially sensitive stimuli" - abstract, concrete or obscene words (the

"sensitive" linkage was auditory, between the target word in Hebrew and words from Russian

lexicon). One category (neutral stimuli) was selected to act as a control condition. Each word

was approximately matched for length and syllables. After completion of the task the

participants were debriefed.

The response times to all the stimuli were monitored, filed and processed. It was assumed,

that bilingual participants are familiar with the obscene Russian slang and monolinguals are

not; the assumption was verified after the completion of the test. Results of participants who

did not meet the criteria (there were six of them) were disqualified.

Materials

The test stimuli were generated using Direct RT software, the program allows response time

calculation as well. Direct RT software is designed by Empirisoft Company (the shareware

version limited to three weeks is downloadable from internet site www.empirisoft.com.) Stimuli were presented on 14" notepad PC monitor in Times New Roman font, with letter

size of 140. The colors were easily extinguished (saturated Green and Red).

18

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Results

Data Preliminary Analysis

Due to extraordinary length (more or less than two syllables), in order to sustain the

equability of the stimuli, four words were eliminated from the initial list. Wrong responses

(1.44% of overall quantity) and answers of extraordinarily long or short response times

(Mean +/- 2 Standard Deviations) were excluded from the final list as well, 343 out of overall

1800 responses were not included in the final list (19.06%). It is important to note, that 188

out of 420 responses to abstract stimuli were eliminated; the validity of "abstract stimuli-

related" results therefore is questionable.

ANOVA

A 4x3 factorial ANOVA showed a significant main effect of participant's group type on the

response time , F (2,228) =3.19, p < .05, although no significant main effect of Stimuli type

F (3,228) =0.295, p > .05. The interaction between variables was not significant,

F (6,228) =0.24, p > .05. The relevant statistical data is presented in "Appendix IV– ANOVA

Table".

Descriptive Data

Interference in Word Processing

380400420440460480500

Neutral

Concre

te

Abstra

ct

Taboo

Stimuli Type

Res

pons

e Ti

mes

(m

icro

seco

nds)

Bilinguals L1 Hebrew

Bilinguals L1 Russian

Monolinguals(Hebrew Only)

"Appendix V" presents means for the three groups in the four conditions. The partial

parallelism of the curves (no intersection) is coherent with the failure to reject the null

hypothesis for interaction test between the Group Type and the Stimuli Type.

19

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Post-hoc analysis

In average, bilinguals responded significantly slower by 8.36% than monolinguals to all

stimuli categories (demonstrating significant main effect of Group Type variable): neutral,

abstract, concrete and taboo. The response times in concrete and taboo conditions differed

significantly (11.05% and 10.53% respectively). In neutral condition the responses of

bilinguals were "delayed" by 5.72% and in abstract condition by 2.47%, both measures

insignificant.

Tukey Post-Hoc test provided no additional insights, while the minimal rejection value for

relevant Dfwithin and k levels (228 and 4 respectively, α=0.05) is 3.63, the maximal Mx vs My

Tukey's HSD test values between the means (drawn from the means table in "Appendix V")

was below 1.5 and therefore none of the differences between the test conditions (stimuli type)

was statistically significant. The HSD values are presented in "Appendix VI".

Chi-Square test revealed that more than 96% of the total variance is attributable to Error,

remaining therefore less than 4% to the main and interaction effects, while the only

significant effect (the group effect) accounts for 2.6% of the variance score only. The

following chart is representing the percentage of each effect's contribution to the total

variance. "Appendix VII" contains the relevant statistical data.

Relative Effect Sizes (Eta Squared)

Group Type, 0.026960214

Stimuli Type, 0.003740854

Group - Stimuli Interaction , 0.006176044

Error, 0.963122888

Group Type

Stimuli Type

Group - StimuliInteraction Error

20

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Discussion

Interpreting Findings

Knowing an additional language slows down the response times in Stroop Color Words task

(significant main effect of Group Type variable). However, seems like the inhibition in

processing is not caused by parallel meaning interference. Namely, neither Hebrew-dominant

nor Russian-dominant bilingual participants did not necessarily activate Russian language

lexicon when the stimuli words in Hebrew were auditory similar to concrete, abstract or

obscene words in Russian. Keeping in mind that Russian-dominant bilinguals generally

performed slower than Hebrew-dominant bilinguals and both bilingual groups performed

slower than monolinguals, appears that the difference in language proficiency is the only

meaningful reason for the inhibition (Russian-dominants have probably less experience

utilizing Hebrew than Hebrew-dominants and certainly than Hebrew monolinguals).

No significant main effects of Stimuli type and interaction were observed. However,

combining the perceivable (but not significant) disparities between group means and the

validation of significant main effect of Group Type allows to claim for a certain coherency of

the results with the hypothesized phenomena: time gaps between the responses of

monolingual-bilingual and Hebrew dominant –Russian dominant participant groups were

larger in concrete and taboo than in neutral conditions (the results of the abstract cluster are

questionable due to the multiple exclusion of responses). It can be speculated, that the

explanation of the differences lies in the hypothesized second-language interferences and not

in Hebrew proficiency level solely; we would have expected similar differences in all stimuli

categories if the their only cause was "language utilizing experience".

Revising the Phenomenon of Interlingual Interference

Because the field of bilingualism is still relatively new, studies in the linguistics,

psycholinguistics, language development and neurolinguistics of bilingualism have often

produced conflicting results; the findings of the current work (the absence of main stimuli

type and interaction effects) were analyzed via different prisms, each representing a distinct

perception of the issue.

According to Dual-Coding Theory (Paivio & Desrochers, 1980; Paivio & Lambert, 1981), the

imagery system and the two verbal systems corresponding to each language of the bilingual

are independent although partly interconnected. The independency explains the ability of

21

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

bilinguals to encode, store and retrieve non-verbal objects (images) without any interventions

from either of the verbal systems. Seems, that stimuli type effect didn't appear because the

participants of the current research treated the presented stimuli as images, which allowed

them to avoid the activation of verbal networks upon the recognition of the color. In order to

verify the hypothesis, an alternative (auditory) form of stimuli representation might be used.

Grosjean (1999) claims, that the core issue in bilinguals' communication is the language

mode his mind is set-up. Language mode is "the state of activation of the bilingual’s

languages and language processing mechanisms at a given point in time" and it depends on

the environmental context; among bilinguals the preferred activation language of a

monolingual will be L1, while among his L2 monolinguals the focus will be on L2. Since the

test was presented in Hebrew, including the performance instructions and the language of the

application, the participants "switched" their brains to "Hebrew mode" priory to the

performance of the task and therefore did not recognize the auditory hints as Russian words.

In order to verify the assumption, an additional research with test instructions in L1 for

bilingual participants is required.

If the two languages of a bilingual share the same script, a visually presented stimulus from

either language has been found to activate words from both languages. Clear evidence of that

can be found in a research on the non-selective nature of lexical access (Altenberg and

Cairns, 1983; Dijkstra, Van Jaarsveld, & Ten Brinke, 1998; Nas, 1983). In this case, when

there is a language switch, bilinguals do not have to deactivate one lexicon and activate the

other because both lexicons are simultaneously active. In the current research, the languages

distinct orthographically and the activation of another (Russian) script is not automatic; it

might require an additional processing time. However, once the appropriate lexicon has been

activated, no extra time should be required during the verification process because the only

set of lexical representations available for examination belongs to the target language

(Kirsner et al., 1984) and therefore semantic networks in Russian remain "activated" and the

response to the color doesn’t involve additional cognitive processing of the word in a parallel

language. Since no significant time differences observed between monolinguals and

bilinguals as a response to the first word (the word "krova" was expected to be easily auditory

recognizable as a concrete word in Russian "korova" – "a cow" causing bilinguals to "switch"

the language mode from Hebrew to Russian) – apparently no "switching procedure" was

22

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

performed by Russian-speakers. Namely, they didn't notice the secondary meaning of the

presented stimuli at all, which explains the absence of the stimuli type main effect.

Recent work on the emotional Stroop paradigm (McKenna & Sharma 2004) has provided

evidence that using negatively valenced emotional words instead of color words has a

slowing effect primarily on the subsequent trial. The results of the current research did not

demonstrate a significant emotional Stroop-related slowdown since the stimuli did not

activate the relevant verbal networks in the minds of bilingual participants. The ESE

slowdown, whether it is based on attention deficit or on threatening effect (Algom, 2002) was

not observed because it was not initiated; the existence of the effect therefore remains

unclear. The current research clearly has the drawback of the way the stimuli is presented; it

fails to penetrate the automaticity of the human brain.

The significant main effect of Group Type was predicted to occur due to the phenomenon of

"Reverse" or "Inverse" translation (Brysbaert & Duyck, 2004). Bilingual participants

translate the presented stimuli from Hebrew to Russian in order to process it; therefore their

response times are slower. It is probable that the same reason of the Group Type effect

existence is "guilty" for the absence of the Stimuli Type effect: while being occupied with

reverse translation, bilinguals fail to recognize the auditory alikeness of the stimuli with

words in Russian.

Drawbacks and Artifacts of the Current Study; Suggestions for the Future Research

The phonological complexity of a word of stimuli words, if not controlled, might be an

artifact and can severely damage the reliability of the research; therefore the "word-structure"

parameter was added to the word list to cope with the problem and some of the initially

prepared words were removed from the final list. Some researchers investigated the "word-

length effect" (Baddeley et al., 1975; Schweickert & Boruff, 1986) and found, that sequences

with shorter durations were remembered better than sequences with longer durations. Longer

words probably will require longer procession times; therefore we should expect extended

response times when the stimulus is longer. In the present study equal was the only way to

control the stimuli equality, however equalizing the amount of syllables does not always even

the length of the words.

The second possible "underwater rock" that might affect the reliability of the research is the

personal language ability of the participants or, in other words, the internal variance within

the test groups or the level of "bilingual balance" (Brysbaert & Duyck, 2004). A group of

23

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Panteton University researchers (Archonti, Protopapas & Skaloumbakas, 2006) suggest, that

greater Stroop interference was observed in children diagnosed with reading disability

(dyslexia) than in unimpaired children, moreover, poorer reading skills were found to

correlate with greater Stroop interference in the general school population. The distribution of

monolingual population to test groups was not sensitive enough to the personal language

abilities, although the participants' questionnaire, including a question according his fluency

(based on self-report) in Russian might provide some valuable knowledge. The degree of

balance or fluency in bilinguals is always a delicate matter. Some researchers have concluded

that being equally proficient in both one’s languages is more of a cognitive ideal than reality

(Hakuta, Ferdman, & Diaz, 1987). Since there is no widely accepted method of assessing

bilingual proficiency, self reports are quite common in bilingual research. In the present

experiment, self reports were also used, by means of a language questionnaire that was given

to subjects.

The cases where a second language is acquired late, but comes to be the dominant language

were not inquired, this can happen when one immigrates and marries a native speaker of the

L2, and raises children whose dominant language is the L2 (Pavlenko, 2004). It also would be

interesting to test the words that the bilingual participants remembered, Corkin & Kensinger

(2003) claimed, that emotional words are more vividly remembered than the neutral, perhaps

the automatic responses prevented immediate activation of the parallel language, but were

remembered after all (McKay et al, 2004, Siegrist, 1995), although tacitly presented.

Bilinguality is influenced by many variables, such as socioeconomic status, cognitive

development (skills), personality, sociolinguistic proficiency and motivation (Romaine,

1995). None of these variables were measured in the current research. The motivation factor

is particularly important; bilinguals "switch" languages depending on social situation. A

bilingual friend, a manager in a high-tech company has told me that he doesn't speak Russian

with his Russian-speaking engineers because they simply ignore his instructions, probably

feeling that speaking the same "second" language equalizes people even in a manager-worker

conditions. While some of the Russian-speaking Israelis make efforts towards a full

integration into the Israeli society, denying any Russian roots, other separate themselves from

the Israeli culture, feeling more Russian than Israeli. The tendency towards

integration/separation should be controlled.

24

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

It was predicted that between-language competition would be observed from Russian to

Hebrew. But is the interference process symmetrical across languages? Combining a list of

stimuli in Russian with auditory coherency to Hebrew words was considered initially but

eventually turned out to be too complicated; a satisfactory amount of such corresponding

words was not found. An additional problem was locating a control group – Russian speakers

with no proficiency in Hebrew. A "reversed" experiment is required in order to conclude

about the bidirectionality of the measured effect.

The word convergence (hyperonym) problem is another possible obstacle. The meaning of a

word consists of a list of conceptual features, comparable to what one finds in a dictionary

(Levelt, 1989; Roelof, 1992, 1996). For example, the Russian word SLIL (слил) may be

represented by two conceptual features PEED or FLUSHED. If the Russian-speaking

participant wants to express a message containing the concept of the mentioned word, it is

unclear which of the conceptual features PEED or FLUSHED will be activated. The problem

is acute since the classification of the stimuli, either obscene (body excretions considered

obscene) or neutral depends on the participant's interpretation of the word, performed upon

the presentation of the Hebrew stimuli with the same sound )סליל( meaning COIL. In many

cases the underlying conceptual representation of the word is so rich and complex that it can

only be expressed by using that particular word.

The relative frequency of the stimuli in both languages was not controlled. Some of the words

might be obsolete or unfamiliar to majority of Russian-speaking audience. A careful study in

which word frequency is an independent variable may prove insightful. The gender data of the participants was not collected. Although, there is a possibility that the

gender has its effect on the responses in Emotional Stroop task, as Thomson & Platek (2007)

demonstrated, males are probably more affected by sexual jealousy priming while performed

jealousy-based Stroop task and therefore might experience higher emotional interference as a

auditory coherency of L1 stimuli to sexual-jealousy related obscene words in L2.

The co-existence of multiple languages in one brain suggests that sophisticated mechanisms

of segregation and coordination must exist in order to prevent the cross-talk between the

languages (Dehaene, 1999). By improving the comprehension of bilingual processing of

"double-lingual" stimuli, researchers might contribute to practical knowledge of brain

plasticity and critical learning processes.

25

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Is one's conceptual system is changing upon learning another languages? Namely, are

Russian-Hebrew bilinguals more "Russian" or more "Hebrew"? Wolff & Ventura (2003)

claim that Russian-English bilinguals who had learned English patterned in their condition

conceptualizing as English monolinguals, even though they did the experimental task in

Russian. Seems, like learning a second language has its consequences for the underlying

conceptual system, it can change the way one views the world.

26

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

References

Abrams, L., Dyer, J.R., MacKay, D.G., Marian, D.E., Shafto, M., & Taylor, J.K. (2004).

Relations between emotion, memory and attention: evidence from taboo stroop, lexical

decision and immediate memory tasks. Memory and Cognition 32 (3), 474-488.

Afzal, N., Bremner, J.D., Charney, D.S., Elzinga, B., Schmahl, C., Vermetten, E., &

Vythilingam. (2004). M. Neural correlates of the classic Color and Emotional Stroop in

women with Abuse-Related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 55, 612-

620.

Algom, D., Ben David, B., & Levy, L. (2003). The Emotional Stroop Effect as a generic

reaction to threat, not a selective reaction to specific semantic categories. In Berglund, B. &

Borg, E. (Eds.), Fechner Day 2003, 21-25. Stockholm: International Society for

Psychophysics.

Alvarado, J.S., Christman, J.C., Freyd, J.J., Hayes, A.E., & Martorello, S.R. (1998).

Cognitive environments and dissociative tendencies: Performance on the standard Stroop task

for high versus low dissociators. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 12, S91-S103.

Alvarez, C.J., Carreiras, M., & de Vega, M. (2000). Syllable-frequency effect in visual word

recognition: Evidence of sequential-type processing. Psicologica, 21, 341-374.

Alvarez, R.P., Grainger, J., & Holcomb, P.J. (2003). Accessing word meaning in two

languages: an event-related brain potential study of beginning bilinguals. Brain and

Language, 87, 290-304.

Anderson, J.R. (1983). The architecture of cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harward University

Press.

Archonti, A., Protopapas, A., & Skaloumbakas, C. (2006). Reading ability is negatively

related to Stroop interference. In press. (Cognitive psychology).

27

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Armoni, L., Greenshpan, Y., & Gopher, D. (1996). Switching attention between tasks:

Exploration of the components of executive control and their development with training. In

proceeding of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 40th Annual Meeting, 1060-1064.

Philadelphia: HFES.

Aycicegi, A., Gleason, J.B., & Harris, C.L. (2003). Taboo words and reprimands elicit greater

autonomic reactivity in a first language than in a second language. Applied Psycholinguistics,

24, 561-579.

Aycicegi, A., Gleason, J.B., & Harris, C.L. (2003). When is a first language more emotional?

Psychophisiological evidence from bilingual speakers. In Press.

Ayciegi, A., & Harris, C.L. (2003). Bilinguals' recall and recognition of emotion words. In

Press.

Balota, D.A., Larsen, R.J, & Mercer, K.A. (2006). Lexical characteristics of words used in

Emotional Stroop Experiment. Emotion, Vol. 6, No.1, 62-72.

Brysbaert, M., Duyck, W. What number translation studies can learn us about the lexico-

semantic organization in bilinguals? In press.

Blot, K.J., Paulus, P.B., & Zarate, M.A. (2003). Code-switching across brainstorming

sessions: Implications for the revised hierarchical model of bilingual language processing.

Vol. 50 (3), 171-183.

Bradley, B.P., & Mogg, K. (2006). Time course of attentional bias for fear-relevant pictures

in spider-fearful individuals Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1241–1250.

Bowman, H., Sharma, D., Wyble, B. Modeling the slow Emotional Stroop Effect. In press.

28

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Buchner, A., Mehl, B., & Rothermund, K. Artificially induced valence of distractor words

increases the effects of irrelevant speech on serial recall. In press.

Bunting, M.F., & Cowans, N. (2005). Working memory and flexibility in awareness and

attention. Psychological research, Vol.69, No. 5-6, 412-419.

Carlo, M.S., & Sylvester, E.S. (1996). Adult second-language reading research: How may it

inform assessment and instruction. NCAL Technical Report TR96-08.

Cherry, E. C. (1953) Some experiments on the recognition of speech, with one and with two

ears. Journal of Acoustical Society of America, 25(5), pp. 975--979.

Constantine, R., McNally, R. J., & Hornig, C.D. (2001). Snake fear and the pictorial

emotional Stroop paradigm. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25, 757–764.

Condon, C.D., & Weinberger, N.M. (1991). Habituation produces frequency-specific

plasticity of receptive fields in the auditory cortex. Behavioral Neuroscience, 105, 416-430.

Corkin, S., & Kensinger, E.A. (2003). Memory enhancement for Emotional words: Are

Emotional words more vividly remembered than neutral words? Memory and Cognition, 31

(8), 1169-1180.

Corkin, S., & Kensinger, E.A. (2003). Effect of Negative Emotional content on Working

memory and Long-Term memory. Emotion, Vol. 3, No.4, 378-393.

Costa, A., Colome, A., & Caramzza, A. (2000). Lexical access in speech production: The

bilingual case. Psicologica, 21, 403-437.

Dehaene, S. (1999). Fitting two languages into one. Brain, Vol. 122, No.12, 2207-2208

29

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Dijkstra, T., Grainger, J., & van Heuven, W.J.B. (1999). Recognition of cognates and

interlingual homographs: The neglected role of phonology. Journal of Memory and

Language, 41, 496-518.

Ekert-Centowska, A. The asymmetry in bilingual processing: Conceptual/lexical processing

route and the word type effect. In press.

Evans, P.D., Gilbert, S.L., Mekel-Bobrov, N., Vallender, E.J., Anderson, J.R., Vaez-Azizi,

L.M., Tishkoff, S.A., Hudson, R.R., & Lahn, B.T. (2005). Microcephalin, a gene regulating

brain size, continues to evolve adaptively in humans. Science, 309:1720.

French, R.M., & Ohnesorge, C. (1995). Using non-cognate interlexical homographs to study

Bilingual memory organization. In proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of the

Cognitive Science Society, pp.31-36.

Finkbeiner, M., & Nicol, J. (2003). Semantic category effects in second language word

learning. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 369-383.

Federmeier, K.D., Kutas, M. (1998). Minding the body. Psychophysiology, 35, 135-150.

Grosjean, F. (1998). Studying bilinguals: Methodological and conceptual issues.

Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1, 131-149.

Hariots, C., & Nelson, K. (2004). Bilingual memory: the interaction of Language and

Thought. Bilingual Research Journal, 25: 4 Fall, 417-438.

Hariots, C., & Nelson, K. (2004). Focusing on memory through a bilingual lens of

understanding. Bilingual Research Journal 28:2 Summer, 181-205.

Henik, A., Carter, C.S., Salo, R., Chaderjian, M., Kraft, L., Nordahl, T.E., & Robertson, L.C

(2002). Attentional control and word inhibition in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 110,

137-149.

30

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Kieras, D.E., Meyer, D.E., Mueller, S.T., & Seymour, T.L. (2003). Theoretical implications

of articulatory duration, phonological similarity, and phonological complexity in verbal

working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition,

Vol. 29, No.6, 1353-1380.

Kindt, M., & Brosschot, J. F. (1997). Phobia-related cognitive bias for pictorial and linguistic

stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 644–648.

ARTICLE IN PRESS Lamers, M., & Roelofs, A. (2007). Modeling the control of visual attention in Stroop-like

tasks. In press.

Lavy, E., & van den Hout, M. (1993). Selective attention evidenced by pictorial and linguistic

Stroop tasks. Behaviour Therapy, 24, 645–657.

MacLeod, C.M. (1991). Half a century of Research on the Stroop Effect: an Integrative

Review. Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 109, No. 2, 163-203.

Marian, V., & Spivey, M. (2003). Competing activation in bilingual processing: within and

between language competition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 6 (2), 97-115.

McDonald, S.A., Tamariz, M., Thomson, J. (2004). Lexical level vs. conceptual level

connections in bilingual lexicon: evidence from eye movements. In press.

Monsell, S. (2003). Task Switching. Trends in Cognitive Science, Vol. 7, No.3, 134-140.

Paivio, A. Dual-Coding theory and education. (2006). Draft chapter for the conference on

"Pathway to Literacy Achievement for High Poverty Children".

Perani, D., Paulesu, E., Galles, N.S., Dupoux, E., Dehaene, S., Bettinardi, V., Cappa, S.F.,

Fazio, F., & Mehler, J. (1998). The bilingual brain: proficiency and age of acquisition of the

second language. Brain, 121, 1841-1852.

31

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Perez-Edgar K., Fox, N.A. (2003). Individual differences in children's performance during an

Emotional Stroop task: a Behavioral and Electrophysiological study. Brain and Cognition,

52, 33-51.

Platek, S.M., Thomson, J.W. (2007). Facial resemblance exaggerates sex-specific jealousy-

based decisions. Evolutionary Psychology, ISSN 1474-7049, Volume 5(1), pp. 223-231.

Roelofs, A. (2003). Goal referenced selection of verbal action: Modeling attentional control

in the Stroop task. Psychological Review, 110, No.1, 88-125.

Roelofs, A. (2002). How do bilinguals control their use of languages? Bilingualism:

Language and Cognition, 5 (3), 214-215.

Rommetveit, R. (2003). On the role of a "psychology of the second person studies of

meaning, language and mind". Mind, Culture and Activity, 10 (3), 205-218.

Salamoura, A., Williams, J.N. Backward word translation: Lexical vs. Conceptual mediation

or "concept activation" vs. "word retrieval". In press.

Smith, C.J., The role of individual differences in processing words with multiple translations.

In press.

Strayer, D.L, Drews, F.A., & Johnston, V.A. (2003). Cell phone induced failures of visual

attention during simulated driving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 9, 23-32.

Tanenhaus, M.K., Flanigan, H.P., & Seidenberg, M.S. (1980). Orthographic and phonological

activation in auditory and visual word recognition. Memoty and Cognition, 8, 513-420.

Taura, H. (1998). Bilingual Dual-Coding in Japanese returnee students. Language, Culture

and Curriculum, Vol.11, No.1, 47-70.

32

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Ventura. T., & Wolff, P. (2003). When Russians learn English: How the meaning of causal

verbs may change. In proceedings of Twenty-Seventh Annual Boston University Conference

on Language Development, 822-833.

Williams, J.N. (2006). Incremental Interpretation in second language sentence processing.

Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 9 (1), 71-88.

Watts, F., McKenna, F. P., Sharrock, R., & Trezise, L. (1986). Colour-naming of phobia-

related words. British Journal of Psychology, 77, 97–108.

Watkins, M. J., & Peynircioglu, Z. F. (1983). On the nature of word recall: Evidence for

linguistic specificity. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 22, pp. 385–394.

33

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Appendixes

Appendix I: Research group classification

Control group M – Monolinguals (Israeli aborigines); test group BR – Bilinguals with

Russian as a dominant language; test group BH –Bilinguals, Hebrew dominant).

:הגדירי את רמת שליטתך ברוסית\אנא הגדיר.1

לא שולט כלל

שולט ברמה בסיסית

שולט ברמה בינונית

שולט ברמה גבוהה

)ד הארץאם אינך ילי(אנא ציינו את הגיל בו עלית לארץ .2

?)אם רלוונטי לגביך(במשך כמה שנים דיברת רוסית כשפה יחידה .3

Appendix II: Test stimuli sample (1x1 scaled)

34

The Open University of Israel Faculty of Social Sciences BA Psychology Program Ψ 2007–12–30 [email protected]

Appendix III: Task words list classification to groups

Stroop

word

[Hebrew]

English

Transcript

ion

Coherent

word

[Russian]

Coherent

word

meaning

Coherent

word

Type

Word

Length in

syllables

[Hebrew]

Word

Length in

syllables

[Russian] Pis-Lon Slon Elephant Concrete 2 1 פסלון Dig-Lon None None Neutral 2 NA דגלון Pis-Ga Pizda Cunt Taboo (3) 2 2 פסגה Ka-Rov Korova* Cow Concrete 2 3 קרוב Mu-Dag Mudak Looser** Taboo (2) 2 2 מודאג Le-Vad Lebed Swan Concrete 2 2 לבדמהדו Do-Me Dooma*** Thought Abstract 2 2

A-Val Oval**** Oval Concrete 2 2 אבל Da-Chooy Hooy Dick Taboo (3) 2 1 דחוי Sleel Slil Peed Taboo (1) 1 1 סליל Bil-Adi Bliadi Whores Taboo (3) 2 2 בלעדי*Tzel Tzel Target Abstract צל

****

1 1

***Kha-Rush Horosh חרוש

***

Good Abstract 2 2

***Sa-Ruk Soroka סרוק