Intensity of female preference quantified through playback setpoints: call frequency versus call...

-

Upload

rafael-marquez -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

3

Transcript of Intensity of female preference quantified through playback setpoints: call frequency versus call...

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2008, 75, 159e166doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.05.003

Intensity of female preference quantified through playback

setpoints: call frequency versus call rate in midwife toads

RAFAEL MARQUEZ, JAIME BOSCH & XAVIER EEKHOUT

Fonoteca Zoologica, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biologıa Evolutiva,

Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC

(Received 21 July 2006; initial acceptance 20 October 2006;

final acceptance 11 May 2007; published online 17 October 2007; MS. number: 9053)

We quantify and compare female preference for two different acoustic parameters of the male advertise-ment call in two species of midwife toads where females select mates based on call characteristics. The pa-rameters compared were: call repetition rate, a highly variable parameter associated with maleemalecompetition, and call dominant frequency, a parameter with low variability related to male size. Wealso tested whether intensity of female preference was similar when the alternate choices were perceivedat high overall intensities (close range) or lower overall intensities (long range). We use ‘Playback setpoints’a new experimental protocol based on two-speaker playback tests with the female placed in a ferret wheel(treadmill) that keeps her equidistant from the two speakers. The protocol measures preference as a trade-off with perceived call intensity: the ‘a priori’ preferred parameter is not broadcast initially, and the femaleinitially walks towards the speaker emitting the inferior parameter. When the female walks towards thisspeaker the intensity of the opposite speaker is gradually increased until the female turns around and startsher approach towards the ‘a priori’ preferred parameter. At this point the differences in sound intensitybetween the speakers are measured, and the difference is considered to be a measure of female preference.Our results show that female preference for call repetition rate is significantly more intense than that fordominant frequency. Similarly, we find that female preference intensity is higher when stimuli are broad-cast at higher overall intensity indicating that females are more selective at close range.

� 2007 The Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Alytes obstetricans; A. cisternasii; call repetition rate; dominant frequency; female preferences; playbacksetpoints

In anurans, female preference for male advertisement callparameters has been extensively studied in the context ofsexual selection (see reviews in Ryan 2001; Gerhardt &Huber 2002). The intensity of female preference, andmore specifically, the differences in intensity of preferencesfor different call parameters or the differences in intensityof preferences for the same call parameters in differentspecies, have not been sufficiently quantified.

The methodology more commonly used is a two-speakerplayback test (or phonotaxis test), where a sexually re-ceptive female is presented an option of two alternativeacoustical stimuli emitted by two loudspeakers located atopposite sides of an arena. The female expresses her choice

Correspondence: X. Eekhout, Fonoteca Zoologica, Departamentode Biodiversidad y Biolog ıa Evolutiva, Museo Nacional deCiencias Naturales, Jose Gutierrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain(email: [email protected]).

150003e3472/08/$30.00/0 � 2007 The Association for the S

by walking or jumping towards one of the emitted sounds.Although a number of additional measurements have beenconsidered (see Wagner 1998; Bosch et al. 2000, 2003; Bushet al. 2002; Schul & Bush 2002), the more generally ac-cepted measurement of female preference has been to scorewhich was the approached speaker and the more commonapproach to quantifying female preference was to calculatethe proportion of females approaching one speaker versusthe other (Gerhardt 1992). Regardless of the number offemales tested, the proportion of females approachingone option versus the alternative provide a single valueper test: the ratio of females approaching one of the two op-tions (and the complementary value) thus making it onlypossible to compare statistically the results of different teststhrough complex comparisons of limited statistical powerand involving a large number of individual tests involvingmany individuals and repetitions (see Gerhardt 1991,2001; Gerhardt & Huber 2002; Bosch & Marquez 2005).

9tudy of Animal Behaviour. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 75, 1160

We present a new methodology ‘playback setpoints’ thatallows the quantification of intensity of female preferencethus allowing the quantitative comparison of preferencesbetween different types of calling parameters. We use thismethodology to compare intensity of preferences for twoparameters for which previous two-speaker phonotaxistests showed directional selection. The results of an addi-tional set of experiments comparing intensity of femalepreference for traits for which there is no ‘a priori’ informa-tion on the existence of directional selection will bepublished in a forthcoming paper.

We used two continental species of midwife toads(genus Alytes) because their mating calls are properly de-scribed (Heinzmann 1970; Crespo et al. 1989; Marquez& Verrell 1991), and quantitative information about call-ing parameters of the males is available for several popula-tions (Marquez & Bosch 1995). Furthermore, femalepreferences for low frequencies and faster calling rateshave been shown in several previous studies (Marquez &Bosch 1995, 1997a, b, 2003).

We initially address question 1: are female preferencesfor faster calling rate (a highly variable call characteristic,involved in maleemale competition and presumably re-lated to energetic expenditure and or increased risk) moreintense than preferences for lower frequency calls (a callcharacteristic with low intraindividual variation and cor-related with male size)? In addition, we address question 2:are female preferences more intense at higher overall callpressure levels (males located at close range) or at lowercall pressure levels (males located at longer distances)?

METHODS

Test Animals

Gravid common midwife toad females, Alytes obstetri-cans, were collected from the population of Lago de laCueva (Parque Natural de Somiedo, Asturias, Spain,43�0302300N, 6�601000W) between the 28 May and 17 June2003 and gravid female Iberian midwife toads, Alytes cister-nasii, were collected from 30 September to 6 October 2003in Navas del Berrocal, Almaden de la Plata, (Sevilla, Spain,37�4702900N, 6�403000W) and near the city of Merida(Extremadura, Spain, 38�590N, 31�240W). Females were keptin captivity for 1e2 weeks under controlled conditions:housed individually in plastic boxes (29 � 19 � 7 cm,3800 ml approx.) with holes in the cover to allow

ventilation. Unbleached, paper towels moistened withdechlorinated water were used as substrate to maintain hu-midity and to allow the animals to hide. Females were fedad libitum with fly larvae. The boxes were checked everyday to ensure that food was available and that the papertowels remained moist. The boxes were cleaned, and thepaper towels changed at least every other day or as needed.As the experiments were carried near the capture area, theboxes were kept with natural daylight cycle and tempera-ture. All females were released in their original capture sitesupon completion of the tests.

Synthetic Stimuli

Synthetic calls were synthesized at a sampling rate of44.1 kHz and 16-bit resolution with Sound Maker 1.0.4software (RicciSoft, Torino, Italy). A digital tone generatorproduced a pure tone sinusoid with a specific spectral fre-quency. The amplitude envelope was then adjusted toa typical envelope of the population, with the averagevalues of rise time (10 ms for A. obstetricans and15 ms forA. cisternasii) and fall time (90 ms for A. obstetricans and160 ms for A. cisternasii). The values used for frequencyof the stimuli were the mean, þ and � 1.5 standard devi-ation (SD) of the distribution of the male advertisementcalls in nature obtained in previous studies in two naturalpopulations: Merida for A. cisternasii (Marquez & Bosch1995) and Penalara (Madrid) from A. obstetricans (seeTable 1). Data from Penalara were selected because it wasthe nearest population of common midwife toads (A.obstetricans boscai, Arntzen & Garcıa-Parıs 1995) for whichwe had a sufficiently large sample of advertisement callsanalysed (Marquez & Bosch 1995).

Playback Set-up

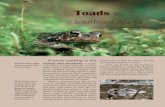

Playback tests were performed in indoor facilities nearboth sites (Navas del Berrocal and Pola de Somiedo). Asummary of the set-up is depicted in Fig. 1. Two Bose X-Treme 1 Control loudspeakers were placed behind a blackcloth wall opposing sides of an arena measuring 1.80 �1.80 m. The speakers were connected to a 12-V batterypowered custom-made sound amplifier with a coarse andfine volume regulation for each channel (Toad Whisperer).Stimuli were played back directly from an Apple Power-book G3 portable computer. Females were placed in a steelferret wheel (23 cm diameter, 9-cm width, 72 cm

Table 1. Values of intensity (settings: LCPeakMax) and distance (mean and standard deviation)

F vs S 63 dB F vs S 75 dB L vs H 75 dB

Fast Slow Fast Slow Low High

Ao Intensity (dB) 57.2 (3.1) 63.0 (0) 68.7 (3.6) 75.0 (0) 74.4 (1.1) 71.3 (4.5)Distance (m) 8.1 (3.0) 3.9 (0) 2.2 (0.9) 1.0 (0) 1.1 (0.2) 1.7 (1.2)

Ac Intensity (dB) 56.6 (3.4) 63.0 (0) 64.5 (6.3) 75.0 (0) 73.3 (4.1) 69.0 (7.0)Distance (m) 12.6 (4.7) 5.6 (0) 6.3 (5.7) 1.4 (0) 2.0 (1.4) 4.4 (6.7)

Values measured at the point where the female ceased to approach the least preferred choice and advanced towards the most preferred choicefor the two alternatives and the three different experiments. Ao stands for Alytes obstetricans and Ac for Alytes cisternasii.

M �ARQUEZ ET AL.: INTENSITY OF FEMALE PREFERENCES 161

L

(a)

(b)

(c) (c)

(d)

(e)

(f)R

Figure 1. Each female was placed in the ferret wheel or treadmill (a), at the centre of an arena 1.80 � 1.80 m (b) between two opposing loud-

speakers placed behind the walls of the arena (light cloth) at the same distance from the wheel (c). The speakers were connected to the audio-

out of a portable Macintosh computer (d), with a custom-made amplifier (e) that allowed the control the volume of each of the speakers in-dependently. Finally, Bruel & Kjaer microphone capsule, connected with a 10-m cable to a Bruel & Kjaer Sound Level Meter (f), was placed

below the midpoint of the wheel. See text for more details.

perimeter) lined with plastic mesh that allowed them towalk inside the wheel while stimulated via either of thespeakers while remaining at the exact same distance be-tween the speakers. On the ground below the midpointof the wheel, a Bruel & Kjaer (DK-2850 Nærum, Denmark)4188 microphone capsule was placed connected througha 10-m cable to a Bruel & Kjaer 2238 Sound Level Meter.To eliminate any potential positional bias, sound channelswere connected randomly to the sound outputs of thecomputer before every night of tests, and channels wereswitched between different test sessions. Prior to the be-ginning of the tests both stimuli were calibrated so thatthey reached the centre of the arena at a maximum of75-dB peak sound pressure level (SPL), or at 63-dB peakSPL depending on the test. Fast versus slow call rate testswere repeated at two different intensities to determinewhether the intensity of female preference was basedsolely on the difference in intensity between the choices(dB difference) or if females also considered the absolutevalue of the intensity of the stimuli (difference in distancefrom the source).

Playback Procedure

The a priori least preferred option was emitted at regularintervals from one of the speakers until the female walked

inside the wheel in that direction. The other speakerremained silent. Figure 2 shows a schematic oscillogram ofthe sequence of call intensities in the different channels.The a priori least preferred option (high frequency orslow rate) was emitted at 75 dB (63 dB in test 3, see below)until the female approached this option turning the wheelat least a whole turn towards the active speaker (the otherspeaker remained silent). Then the test was considered tostart, and, throughout the first 5 min of the test the a priorileast preferred option (high frequency or slow rate) wasemitted at constant intensity, in the last 5 min the inten-sity was decreased gradually from 100% to 0% (see lowerchannel in figure). The a priori preferred option (upperchannel in figure) started increasing its intensity from0% to 100 % linearly, so that at upon completing half ofthe test time (5 min) the intensities of both stimuli wereequalized at 100% amplitude. At this point, the intensityof the a priori preferred option (low frequency or high call-ing rate) remained stable at 100% (75 or 63 dB) until theend of the test while the intensity of the nonpreferredoption decreased linearly.

Thus, all females started the test by approaching thea priori least preferred option and the test was stoppedwhen they reversed their choice by stopping and advanc-ing at least half a wheel towards the a priori most attractivestimulus. This was considered to be the ‘playback setpoint’.At this point the intensity of the stimuli emitted by each

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 75, 1162

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 min

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Low frequency vs high frequency

Fast calling rate vs low calling rate

min

Figure 2. Oscillograms of the alternate stimuli of the tests. Intervals between calls in the figure are increased in the figure to allow a visual

comparison between channels. Note that prior to the beginning of the test, the a priori least preferred alternative (the channel representedbelow in each case) was emitted continuously until the female approached it. The 10-min test began only after the female had completed

one turn inside the wheel walking towards the only speaker that was initially active. (a) Low- versus high-frequency test. The upper oscillogram

is the low-frequency stimulus which increases steadily in intensity over the first half of the test (5 min) the lower oscillogram is the high-

frequency stimulus which decreases linearly in intensity over the second half of the test (5 min). (b) Fast versus slow calling rate. The upperoscillogram is the stimulus emitted at a fast calling rate which increases steadily in intensity over the first half of the test (5 min) the lower

oscillogram is the stimulus emitted at a slow calling rate which decreases linearly in intensity over the second half of the test (5 min).

channel was measured with the Bruel & Kjaer 2238 SPLmeter (Settings: LCPeakMax).

If a female did not move consistently for 2 min at thebeginning of the test or if she did not change directionat any point in the test, the test was considered nil, andthe female was retested for that particular discriminationon a different night. Females that consistently did not ap-pear to approach the source of advertisement calls in thesetests and in other unpublished tests that were performedconcomitantly were thus eliminated from the study.

Tests

Test 1 (L versus H, 75 dB)Females were exposed to a choice between alternating

stimuli of average duration and calling rate reaching thecentre of the arena at 75 dB differing in the dominantfrequency of the call, the choices being: low frequency(�1.5 SD) and high frequency (þ1.5 SD).

Test 2 (F versus S, 75 dB)Females were exposed to a choice between stimuli with

average frequency and duration reaching the centre of thearena at 75 dB differing in the call rate, the choices beinghigh calling rate (þ1.5 SD) versus low calling rate (�1.5 SD).

Test 3 (F versus S, 63 dB)Females were exposed to a choice between stimuli with

average frequency and duration reaching the centre of thearena at 63 dB differing in the repetition rate of the call,

the choices being high calling rate (þ1.5 SD) versus lowcalling rate (�1.5 SD).

To address the first question, the values for ‘playbacksetpoints’ of tests 1 and 2 were compared. To address thesecond question, the values for ‘playback setpoints’ oftests 2 and 3 were compared.

The intensities of the stimuli at the ‘playback setpoint’were used to infer the hypothetical distances betweensources of the stimuli and female position. To calculatethese values, we used two mathematical equations: A.cisternasii, Distance ¼ (4517.9 � exp (�0.116735 � SPL)):A. obstetricans, Distance ¼ (8607.04 � exp (�0.116735 �SPL)) built with intensity data of source levels (SPL indBpeak) of advertisement calls obtained in the field (A. cis-ternasii, mean C peak 83.9 dB; A. obstetricans, mean C peak80.8 dB; Marquez et al. 2006). Therefore, for every ‘playbacksetpoint’ we calculated the inferred distance betweenfemale position and the sources of the stimuli, assumingthat the stimuli were emitted by two males calling with anaverage source level (standard intensity) and assuming noexcess attenuation (6 dB increase per doubling of the dis-tance). Then, we calculated the ratio between the distancefrom the female position to the a priori most attractivestimulus, and the distance from the female position to thea priori less attractive stimulus. We used the ratio betweendistances instead of the difference between distancesbecause initial distances between speakers differed betweenspecies when corrected by their species-specific averagesource levels.

The ratios of the distances at the ‘playback setpoint’between species and tests were analysed by using a two-way analysis of variance with Statistica 6.0 software

M �ARQUEZ ET AL.: INTENSITY OF FEMALE PREFERENCES 163

(Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, U.S.A.). The factor ‘test’ took intoaccount the variation on the ratio of the distancesbetween alternatives among the different three performedtests, while the variation originated in the species-specificresponse was assessed with the factor ‘species’, includingtwo levels (A. cisternasii and A. obstetricans). When theanalysis detected significant differences for one of the fac-tors in the model, we used a posteriori comparisons toidentify which experiments were significantly differentfrom each other (Tukey tests).

RESULTS

Twenty-two A. obstetricans females and 18 A. cisternasii fe-males responded to the three tests. The ‘set points’, or thevalues of the difference in intensity at the point where thefemale ceased to approach the a priori least preferredchoice and advanced towards the most preferred choicefor the three different tests are shown in Table 1. Thevalues for the high option in the test ‘L versus H 75 dB’were not exactly 75 because most females of both species(15 of 18 for A. cisternasii and 16 of 22 in A. obstetricans)only changed the direction of their approach in the sec-ond half of the experiment when the low-frequency callwas higher in intensity than the high-frequency call.

Ratios between distances were greater for A. cisternasiithan for A. obstetricans (F1,38 ¼ 6.1, P ¼ 0.0185), and dif-fered among the three performed tests (F2,76 ¼ 21.9,P < 0.001). Ratios between distances were greater for thetest 2 (F versus S 75 dB), and weaker for the test 1 (L versusH 75 dB, Fig. 3); this suggests that females reversed theirchoice when differences in sound intensity were greaterin test 1 than in test 2, further suggesting that female pref-erence intensity was higher when choosing (F versus S 75dB), than when choosing (L versus H 75 dB). The fact thatthe values of ratios between distances for test 1 were closeto 1 indicates that female preference in this test waschanged very close to the point of equal intensity betweenthe stimuli.

Additionally, the effects of species identity and kind oftests were not mutually independent, as the species*testinteraction was significant. There was no significant

6

5

4

3

2

1

0L vs H 75dB F vs S 75dB F vs S 63dB

Dis

tan

ce t

o m

ost

attr

acti

veal

tern

ativ

e/d

ista

nce

to

less

attr

acti

ve a

lter

nat

ive

Figure 3. Results of the comparison of the ratio of the distances at

the ‘playback setpoint’ between species and tests obtained from

a general linear model with Statistica 6.0 software. Open squaresrepresent female Alytes obstetricans and solid circles, female Alytes

cisternasii.

change in the responsiveness related to sound pressurein A. obstetricans but the change was significant in A. cister-nasii (Fig. 3).

When both species were considered together, the a pos-teriori Tukey tests indicated that the outcome of F versus S75 dB was different from all the other experiments(P < 0.05 in all cases). On the other hand, when differencesbetween species and experiments were considerer together,the a posteriori Tukey tests indicated that ratios betweendistances differed only in 5 of 15 comparisons (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The significance of the observed difference between tests 1and 2 provides the answer to question 1: for A. cisternasii,female preference for call rate is significantly more intensethan for call dominant frequency, as shown in Bosch &Marquez (2005). While A. cisternasii females could notchoose to cover an additional distance (ratio between dis-tances: 1.02) to reach the most attractive male when com-petitor’s quality differs in dominant frequency, they couldchoose to cover up to 4.5 times the distance to reach themale calling at faster rate. This result is also in agreementwith the observations of Gerhardt (2001) based on manytests performed with North American species of Hylaand with the general idea that sexual selection operatesmostly on proximate, highly variable characters or ‘perfor-mance’ (sensu Arnold 1983) related to issues such as ener-getic expenditure, hormonal state or stamina, thanselection on other characters such as size or longevity,which are less dynamic variables, and thus less prone tobeing involved in maleemale competition (although per-haps more reliable potential indicators of ‘good genes’).The significance of the effect ‘species’ indicates that theobserved responses differ between both species at the‘playback setpoint’. Alytes cisternasii presents greater ratiosbetween distances for test 2; therefore females of this spe-cies are willing to cover longer distances to reach the mostattractive male (4.5 times larger in A. cisternasii versus 2.2times larger in A. obstetricans). The fact that the matingseason of A. cisternasii is substantially shorter than thatof A. obstetricans (Marquez 1992) makes this an additionalexample of a case where sexual selection is more intensein the more explosive breeder than in the more prolongedbreeder (sensu Wells 1977).

Table 2. Tukey test

Ao

L vs H

75 dB

Ao

F vs S

75 dB

Ao

F vs S

63 dB

Ac

L vs H

75 dB

Ac

F vs S

75 dB

Ao L vs H 75 dB dAo F vs S 75 dB ns dAo F vs S 63 dB ns ns dAc L vs H 75 dB ns ns ns dAc F vs S 75 dB *** ** *** *** dAc F vs S 63 dB ns ns ns ns **

Results of a posteriori tests to identify experiments which were signif-icantly different from each other (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01; ns, notsignificant).

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 75, 1164

The observed difference between tests 2 and 3 respondsto question 2: for A. cisternasii, the intensity of femalepreference is not independent of the absolute sound levelreaching the female. At the higher SPL values females ap-peared to have higher preference intensities. Our result isin agreement with Gerhardt’s observations for NorthAmerican Hylas that led him to conclude that ‘preferencesare likely to depend on both absolute and relative differ-ences in amplitude’ Gerhardt 2001, p. 125). If we considerthat call intensity is strongly determined by distance be-tween caller and receiver, we could further conclude thatfemale preference for call rate is more intense at closerange (higher SPL) than it is at longer range (lower SPL).This observation is consistent with the expected patternof approach of female anurans to male calling aggrega-tions, where distant calls perceived at low intensity pro-vide information for the general attraction to thebreeding grounds, and choice occurs when the female iswithin short range of male callers, when the calls reachher with high SPL values (Gerhardt 2001). Alternatively,and given that the difference in distance represented bythe same difference in SPL values is higher when SPLvalues are low, this result would support the idea that fe-males are less prone to change their preference when thedifference in distance between options is higher (i.e.when they would have to travel a longer extra distanceto reach the preferred option). A similar result was re-ported by Gerhardt et al. (1996) in a behavioural studyof female preference in two species of grey treefrogs thatshowed that preferences were stronger when intensitywas higher (closer speaker distance). The better discrimi-nation of A. cisternasii at high intensity levels is consistentwith the results in green treefrogs, Hyla cinerea (Gerhardt1987; Gerhardt & Huber 2002) where it was hypothesizedthat the result reflected differences in the absolute sensi-tivity of the two auditory organs: amphibian papilla (lowthreshold) and basilar papilla (high threshold) especiallyconsidering that the frequencies of midwife toad callsmatch the sensitivity of their basilar papillae (Bosch &Wilczynski 2003). The observed results are, however,against those expected considering the neuroethologicalobservations of Schwartz & Gerhardt (1998), that foundin spring peepers, Pseudacris crucifer, that the normalizedisointensity profiles of midbrain recordings were less flatat high intensities (close range). If the neuroethologicalstudies of A. cisternasii reveal a similar trend, the explana-tion may suggest the existence of preference mechanismbeyond the level of the midbrain. In A. obstetricans, how-ever, the difference observed between tests 2 and 3 wasnot significant. This result suggests that for this species, fe-male preference intensity does not change significantlywhether females are listening to males at close range or fur-ther away. The setpoints observed are above the hearingthresholds in the frequency range of the conspecific calls,which are about 52- and 46-dB peak SPL for A. cisternasiiand A. obstetricans, respectively (J. Bosch et al., unpub-lished data). If A. obstetricans is endowed with a better au-ditory sensitivity relative to A. cisternasii, as indicated bythis difference. The lack of difference between tests 2 and3 for A. obstetricans is congruent with a better auditory sen-sitivity. Detection of the stimulus delivered with steps of

increasing intensity will be detected earlier at the low-level(63 dB) experiment by females of A. obstetricans as com-pared with A. cisternasii. However, the higher setpointsmeasured for this species relative to A. cisternasii suggestthat female preference may be a different process thanmere improved call detection (in both species all of theset points measured in individual females occur whenthe stimulus with the lowest intensity is well above hear-ing threshold). It is possible, however, that a discriminationtask with an alternative stimulus at a fixed level is harderfor animals having lower auditory thresholds, since thesystem is closer to the upper limits of the dynamic range.

The methodology of ‘acoustic setpoints’ used in ourstudy is an approach for measuring female preference,which is intermediate to the measurements of ‘absolute’and ‘relative preference functions’ discussed by Wagner(1998). Although our approach does not reveal preferencefunction shape, by using population landmarks (þ and �1.5 SD) in both effects it allows quantitative comparisonsbetween tests of different traits probably in a more efficientfashion than attempting to measure the amount of move-ment towards sequentially presented stimuli (Doherty &Pires 1987; Wagner et al. 1995). Similarly, it is not necessaryto assess a complete behavioural repertoire to quantify pref-erence (Bosch et al. 2003).

The methodology of ‘acoustic setpoints’ is a techniquethat can be applied to other walking, running and jumpingfrogs (and perhaps climbing frogs). It is similar in inceptionbut simpler than the approach described in Gerhardt et al.(2000) where the preference of females Hyla versicolor forlonger calls was tested repeatedly with increasing call inten-sity differences at steps of 3 dB. It is also faster than that ofMurphy & Gerhardt (2000) who tested female Hyla gratiosamultiple times with each stimulus set (of two alternativechoices) to determine ‘to some extent’ the strength of fe-male preference for each alternative. Similarly, this method-ology would have allowed the quantitative comparison ofthe effect of absolute SPL on the high- and low-frequencyspectral peaks of H. cinerea (see Fig.7 of Gerhardt 2001). Itis also faster than other studies where female preferenceswere repeated at different intensities (such as Gerhardtet al. 1996; Gerhardt 2005).

The methodology of ‘acoustic setpoints’ does not allowfor the quantification of individual repeatability, but mostattempts at measuring this variable with anuran femalechoice in playback tests have shown that repeatability isgenerally low (Howard & Young 1998; Kime et al. 1998;Murphy & Gerhardt 2000, but see also Jennions & Petrie1997; Gerhardt et al. 2000).

Although ‘acoustic setpoint’ methodology does not pro-vide an estimate of the shape of the female preferencefunction over the distribution of male, it is also a fasteralternative to compare intensities of preferences betweentraits than that provided by the set of six two-speaker testsused by Bosch & Marquez (2005) for A. cisternasii, to approx-imate the shape of the female function. Their results in thecomparison of preferences for call rate versus dominantfrequency are consistent with the quantitative results ob-tained by us with the ‘acoustic setpoints’. It is also techni-cally less complex than the multispeaker playback testsused by Schwartz (1993) and by Marquez & Bosch (1997a).

M �ARQUEZ ET AL.: INTENSITY OF FEMALE PREFERENCES 165

Moreover, ‘acoustic setpoint’ playback tests are also simplerto perform than the experimental approach used by Bushet al. (2002), because it does not require multiple tests toobtain a test score from each female.

Adaptations of this methodology to other study animalscould also be envisioned: for example, use in phonotaxisplayback tests with insects only requires the design ofa suitable device to maintain a walking insect in a stationarylocation. Similarly, visual stimuli could also be compared,for instance by changing the perceived distance of a stim-ulus by increasing or decreasing the size of a displayinganimal in a test of alternative choices. Such a set-up couldbe applicable to studies of fish behaviour, or for otherspecies with visual displays. Additional uses of this meth-odology to quantify intensity of female preferences inanurans are in progress.

The observed low intensity of female preference for calldominant frequency (reversal occurs often when calls reachthe female with similar intensities) suggests that thetraditional two-speaker playback tests may detect behav-ioural biases that are not likely to have substantial ecolog-ical or evolutionary consequences because there will be veryfew cases in which females in nature will have to selectbetween two alternative calls reaching her with identicalintensity. In the many species of acoustical animals wheresimilar trends have been described with two-speaker play-back tests, caution should be used when assuming the directconnection between significant female preferences andselective effect. In the case of the midwife toads, theobserved large-male mating advantage in the field (Reading& Clarke 1988; Marquez 1993) probably has to be explainedthrough other relationship in addition to that of male size,call dominant frequency, and female preference for largermales. Concerning the divergent results observed betweenspecies regarding the change in intensity of female prefer-ence with call sound pressure level, two general conclusionscan be reached: (1) there are relevant preference mecha-nisms that operate well above hearing threshold, and (2)these mechanisms appear to be different in related specieswith extremely similar acoustical communication systems.Furthermore, studies including the quantification of the pref-erence reversal should be addressed in different acousticalspecies to seek for more generalized patterns.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our thanks for the permits for thecapture of A. obstetricans and for the use of the SomiedoNatural Park facilities that were kindly provided by theConsejerıa de Medio Ambiente, Principado de Asturias,and the Direction of the Park (Mr Cecilio Ruano). Wealso want to thank the Delegacion Provincial de MedioAmbiente of Sevilla and specifically to Mr Javier Cobo offor providing permits for A. cisternasii and providing lodg-ing in Navas del Berrocal. We also extend our thanks to allthe personnel of P. N. Somiedo and P. N. Sierra Norte deSevilla who were always most helpful and understandingwith our nocturnal activities. Dr R. G. Bowker kindly im-ported into Spain the ferret wheel used for the tests. C.Ana, and C. Moreira, provided valuable help with the

tests. Dr M. Tejedo was most helpful with the logistics ofthe southern site. This research was funded with projectproject BMC 2000-1139 (PI: R. Marquez) Ministerio deEducacion y Cultura of Spain. The Fonoteca Zoologica ofthe Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC) inMadrid provided support for the sound analyses (Project07M/0083/02 Comunidad de Madrid). X. Eekhout wasthe recipient of a predoctoral grant from the Comunidadde Madrid. M. Penna contributed valuable comments onthe manuscript.

References

Arnold, S. J. 1983. Morphology, performance and fitness. American

Zoologist, 23, 347e361.

Arntzen, J. W. & Garcıa-Parıs, M. 1995. Morphological and allozyme

studies of midwife toads (genus Alytes), including the description oftwo new taxa from Spain. Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde, 65, 5e34.

Bosch, J. & Marquez, R. 2005. Female preference intensities on dif-

ferent call characteristics and symmetry of preference above andbelow the mean in Alytes cisternasii. Ethology, 111, 323e333.

Bosch, J. & Wilczynski, W. 2003. The auditory tuning of the Iberianmidwife toad, Alytes cisternasii. Herpetological Journal, 13, 53e57.

Bosch, J., Rand, A. S. & Ryan, M. J. 2000. Signal variation and callpreferences for the whine frequency in the tungara frog, Physalae-

mus pustulosus. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 49, 62e66.

Bosch, J., Marquez, R. & Boyero, L. 2003. Behavioural patterns,

preference, and motivation of female midwife toads during

phonotaxis tests. Journal of Ethology, 21, 61e66.

Bush, S. L., Gerhardt, H. C. & Schul, J. 2002. Pattern recognition

and call preferences in treefrogs (Anura: Hylidae): a quantitative

analysis using a no-choice paradigm. Animal Behaviour, 63, 7e14.

Crespo, E. G., Oliveira, M. E., Rosa, H. C. & Paillette, M. 1989.

Mating calls of the Iberian midwife toads Alytes obstetricans boscaiand Alytes cisternasii. Bioacoustics, 2, 1e9.

Doherty, J. A. & Pires, A. 1987. A new microcomputer-basedmethod for measuring walking phonotaxis in field crickets (Grylli-

dae). Journal of Experimental Biology, 130, 425e432.

Gerhardt, H. C. 1987. Evolutionary and neurobiological implications

of selective phonotaxis in the green treefrog, Hyla cinerea. Animal

Behaviour, 53, 1479e1489.

Gerhardt, H. C. 1991. Female mate choice in treefrogs: static and

dynamic acoustic criteria. Animal Behaviour, 42, 615e635.

Gerhardt, H. C. 1992. Conducting playback experiments and inter-

preting their results. In: Playback and Studies of Animal Communica-

tion (Ed. by P. K. McGregor), pp. 59e77. New York: Plenum.

Gerhardt, H. C. 2001. Acoustic communication in two groups of

closely related treefrogs. Advances in the Study of Behavior, 30,99e167.

Gerhardt, H. C. 2005. Advertisement-call preferences in diploid-tetraploid treefrogs, Hyla chrysoscelis implications for mate

choice and the evolution of communication systems. Evolution,

59, 395e408.

Gerhardt, H. C. & Huber, F. 2002. Acoustic Communication in Insects

and Anurans. Common Problems and Diverse Solutions. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Gerhardt, H. C., Dyson, M. L. & Tanner, S. D. 1996. Dynamic

properties of the advertisement calls of grey treefrogs: patternsof variability of female choice. Behavioral Ecology, 7, 7e18.

Gerhardt, H. C., Tanner, S. D., Corrigan, C. M. & Walton, H. C.2000. Female preference functions based on call duration in thegrey treefrog Hyla versicolor. Behavioral Ecology, 11, 663e669.

Heinzmann, U. 1970. Untersuchungen zur bio-akustik und okologieder geburtshelferkrote. Oecologia, 5, 19e55.

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 75, 1166

Howard, R. D. & Young, J. R. 1998. Individual variation of male

vocal traits and female preferences in Bufo americanus. Animal

Behaviour, 55, 1165e1179.

Jennions, M. D. & Petrie, M. 1997. Variations in mate choice and

mating preferences: a review of causes and consequences. Biolog-ical Reviews (Cambridge), 72, 283e327.

Kime, N. M., Rand, A. S., Kapfer, M. & Ryan, M. J. 1998. Consis-tency of female choice in the tungara frog: a permissive preference

for complex characters. Animal Behaviour, 55, 641e649.

Marquez, R. 1992. Terrestrial paternal care and short breeding

seasons: reproductive phenology of the midwife toads Alytes

obstetricans and A. cisternasii. Ecography, 15, 279e288.

Marquez, R. 1993. Male reproductive success in two midwife toads

(Alytes obstetricans and A. cisternasii). Behavioural Ecology and

Sociobiology, 32, 283e291.

Marquez,R. & Bosch, J.1995. Advertisement calls of the midwife toads

Alytes (Amphibia,Anura, Discoglossidae) incontinental Spain. Journalof Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research, 33, 185e192.

Marquez, R. & Bosch, J. 1997a. Female preference in complexacoustical environments in the midwife toads Alytes obstetricans

and Alytes cisternasii. Behavioral Ecology, 8 (6), 588e594.

Marquez, R. & Bosch, J. 1997b. Male advertisement call and female

preference in sympatric and allopatric midwife toads (Alytes obstet-

ricans and Alytes cisternasii). Animal Behaviour, 54, 1333e1345.

Marquez, R. & Bosch, J. 2003. Temporal encoding of information in

the advertisement call of the Iberian midwife toad (Alytes cisternasii).

The importance of rise time. Behaviour, 140, 113e123.

Marquez, R. & Verrell, P. 1991. The courtship and mating of the

Iberian midwife toad, Alytes cisternasii (Amphibia, Anura, Disco-glossidae). Journal of Zoology (London), 225, 125e139.

Marquez, R., Bosch, J. & Penna, M. 2006. Sound pressure level of

advertisement calls of Alytes cisternasii and Alytes obstetricans

(Anura, Discoglossidae). Bioacoustics, 16, 27e37.

Murphy, C. G. & Gerhardt, H. C. 2000. Mating preference func-

tions of individual female barking treefrogs, Hyla gratiosa, fortwo properties of male advertisement calls. Evolution, 54,

660e669.

Reading, C. J. & Clarke, R. T. 1988. Multiple clutches, egg mortality

and mate choice in the mid-wife toad, Alytes obstetricans. Am-

phibia-Reptilia, 9, 357e364.

Ryan, M. J. 2001. Anuran Communication. Washington and London:

Smithsonian Institution Press.

Schul, J. & Bush, S. L. 2002. Non-parallel coevolution of sender

and receiver in the acoustic communication system of tree-

frogs. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B, 269,1847e1852.

Schwartz, J. J. 1993. Male calling behavior, female discriminationand acoustic interference in the neotropical treefrog Hyla microce-

phala under realistic acoustic conditions. Behavioral Ecology and

Sociobiology, 32, 401e414.

Schwartz, J. J. & Gerhardt, H. C. 1998. The neuroethology of

frequency preferences in the spring peeper. Animal Behaviour,

56, 55e59.

Wagner, W. E., Jr. 1998. Measuring female mating preferences.

Animal Behaviour, 55, 1029e1042.

Wagner, W. E., Jr, Murray, A. M. & Cade, W. H. 1995. Phenotypic

variation in the mating preferences of female field crickets, Gryllusinteger. Animal Behaviour, 49, 1269e1281.

Wells, K. D. 1977. The social behavior of anuran amphibians. AnimalBehaviour, 25, 666e693.