INIZIO PARTE ANDREA - Statistiska centralbyrån (SCB) · Web viewperformance and potentialities by...

Transcript of INIZIO PARTE ANDREA - Statistiska centralbyrån (SCB) · Web viewperformance and potentialities by...

Inbound tourism in Italian regions:

performance and potentialities

by Giovanni Giuseppe Ortolani, Andrea Alivernini and Luca Buldorini

2004

v. 1.0

INBOUND TOURISM IN ITALIAN REGIONS: PERFORMANCE AND POTENTIALITIES

by Giovanni Giuseppe Ortolani, Andrea Alivernini and Luca Buldorini *

Abstract

Tourism is one of the traditionally 'strong' sectors of Italy’s economy. Nevertheless, the position in the ‘life-cycle’ of the various destinations, considered as tourism products offered to visitors, is significantly differentiated among regions. Some regions appear to be touristically ‘mature’, whereas others seem to be at earlier stages of tourism development. The study identifies the geographical areas with the highest growth potential, i.e. the regions that in principle should be focused on by policy-makers. At the same time, the research provides hints on the potential development that an optimal exploitation of tourist resources could generate, taking into account the constraint of the availability of local human resources.

The study makes use of data produced by UIC and national statistical office (ISTAT). In the paper, three main methodological tools are applied. The estimation procedure to make up for the lack of official statistics on domestic tourism expenditure can be considered an original contribution. Whereas, the methodologies to assess the regional tourist ‘attractiveness’ and to calculate the impact of internal tourism expenditure in terms of value added and employment are largely derived from previous studies of TCI (Touring Club Italiano) and CISET (Centro Internazionale di Studi e Ricerche sull'Economia Turistica).

* Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi, Statistics Department

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not involve the responsibility of the Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi.

2

Table of Contents

1. Introduction....................................................................................................................................4

2. Estimation of Italy's internal tourism expenditure.........................................................................6

3. Main features of Italy's internal tourism expenditure patterns....................................................10

4. Tourism attractiveness of Italian regions.....................................................................................14

5. Tourism and regional development.............................................................................................19

6. Concluding remarks.....................................................................................................................21

7. References....................................................................................................................................23

3

1. Introduction1

Traditionally, international travel plays a remarkable role in balance of payments (b.o.p.) statistics, as the

associated expenditure represents an important component of the current account balance (in the Travel item,

part of Services) of an economy. For this reason, special attention has been constantly devoted, in the b.o.p.

domain, in measuring travellers'2 expenditure. Moreover, in tourism statistics there is a growing interest in

isolating and studying the economic impact of tourism activities, both international and domestic. This has

eventually led, in recent years, to the definition of a new set of statistics, the Tourism Satellite Account3

(TSA), which considers tourism activities as a specific and peculiar type of demand, generating a certain

level of consumption (expenditure)4 of goods and services supplied by a diversified range of economic

sectors. Thanks to the TSA, production, employment and income generation in the various sectors of the

economy can be analysed as directly or indirectly triggered by travellers.

This study attempts to combine the b.o.p. and tourism statistics concepts and sources in order to reach a

twofold objective:

1) to assess the potential tourist attractiveness of Italian regions and their present capability to exploit this

potential in order to 'capture' tourism expenditure and

2) to provide hints on the possible economic development that Italian regions could gain from the

improvement of the exploitation of their tourist attractiveness, taking into account the possible constraint

of the availability of local labour force.

The first objective requires the quantification of the present level of Italy's internal, i.e. both inbound and

domestic, tourism expenditure. Similarly to most countries, Italy's inbound tourism expenditure is quite

1 Although the overall responsibility for the paper is shared by the three authors, Giovanni Giuseppe Ortolani wrote paragraphs 1 and 6, Andrea Alivernini wrote paragraph 3 and Luca Buldorini wrote paragraphs 2, 4 and 5. The authors are especially grateful to Antonello Biagioli and Pietro Mascelloni, of UIC's Statistics Department for useful discussions and comments at different stages of the research.2 In this paper, following the definitions of the International Monetary Fund on balance of payments statistics [International Monetary Fund (1993), Balance of Payments Manual - Fifth Edition, Washington DC - BPM5 in the following], the 'statistical unit' considered is the traveller. It should be noted that the concept of traveller adopted here broadly corresponds with the concept of visitor used in tourism statistics. In the following, the terms 'traveller' and 'visitor' are used as synonyms, both in the international and domestic tourism contexts.3 The conceptual reference of the TSA was set in European Commission, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, World Tourism Organization, United Nations (2001), Tourism Satellite Accounts: Recommended Methodological Framework. Luxembourg - Paris - Madrid - New York. Guidelines for the implementation of TSA in the European Union Member States can be found in Eurostat, European Implementation Manual on Tourism Satellite Accounts, 2002, Luxembourg.4 This paper uses consumption and expenditure as synonyms.

accurately covered by current official sources, whereas domestic expenditure is not5. Therefore, a substantial

part of the study concerns the development of an original methodology to estimate the approximate

magnitude of the expenditure originating from trips of residents within the Italian territory, broken down by

Italian destination region.

This study builds on a previous analysis carried out some years ago6, whose focus was the substantial

underdevelopment of inbound tourism in Italy's southern regions. To this end, a set of attractiveness

indicators was designed, on the basis of a comprehensive inventory of cultural, environmental and social

assets of each region. The potential increase of inbound tourism expenditure in the South of the country that

an 'ideal' exploitation of tourist resources could promote was subsequently estimated. Finally, the expansion

of inbound expenditure was translated, trough an input-output model, into the expected growth of valued

added and employment in those regions.

Differently from the earlier analysis, this study does not concentrate on southern Italy, as it considers all

regions. This enlargement of the scope of the investigation aims at assessing the level of tourist efficiency

and the general economic feasibility of its improvement in each local context, through a more open,

exploratory approach.

The present analysis is meant to prompt the discussion on the topics presented, rather than to provide

'conclusive' findings, as several weaknesses of the study have to be recognised. Among the most relevant we

point out three aspects. First, the approximation of the model adopted to estimate, because of the mentioned

lack of relevant official statistics, Italy's domestic tourism expenditure. Second, the substantial fuzziness of

the concept of tourism attractiveness of the regions and the difficulties for its quantification. Third, the

simplified modelling of the potential economic impact of an ideal tourism development. All these aspects

can be significantly improved through further efforts.

All data in the present study refer to the situation in the year 2002, i.e. the more recent year for which

complete official statistics on all relevant dimensions were available at the time the paper was written.

The paper is structured as follows. Paragraph 2 illustrates the methodology used to obtain an as much as

possible complete picture of total Italy's internal tourism expenditure, with details on the approach used to

the estimate the domestic part. Paragraph 3 contains a brief description of the main characteristics of the

country's internal tourism demands, analysing both the physical and monetary variables, broken down by the

most significant classification attributes (type of accommodation used and country of origin). Paragraph 4

introduces the concept of tourism attractiveness of a region and its operationalization. Paragraph 5 depicts

5 Non-official statistics on the regional distribution of Italy's domestic tourism expenditure are regularly jointly elaborated by IRPET (Istituto Regionale per la Programmazione Economica della Toscana) and CISET; see Manente, M., "Il turismo nell'economia italiana" in Becheri, E. et al. (2003), XII Rapporto sul turismo italiano, Firenze. Nevertheless, this source does not provide the data details (type of accommodation , purpose of travel, visitors' country of origin) needed for part of the analysis conducted in the present study.6 See Touring Club Italiano - Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1998), Turismo estero al Sud: una occasione di sviluppo, Roma and Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1998), The Geography of International Tourism Demand in Italy, Roma.

5

the ideal scenario of tourist and economic development for each region, taking into account the constraint of

the locally available human resources. Paragraph 6 reports the conclusive considerations.

2. Estimation of Italy's internal tourism expenditure

Despite the economic importance of the tourism sector, several difficulties hinder the possibility to derive a

fully comprehensive picture of visitors' expenditure in Italy from the currently available sources. In the first

place, the definition of the reference population, namely of the individuals to be concretely addressed when

trying to measure the phenomenon, poses major difficulties. People travel for many different reasons and,

depending on the purpose of their travelling, not all travellers are considered equally relevant. As an

example, tourism statistics do not consider "commuting trips" (individuals moving to reach their usual

working location) as part of tourism activity; this involves the need to identify such travellers within the

larger population of travellers, in order to exclude their expenses from tourism analysis. Also problematic is

the definition of the concept of "usual environment", which delimits the area beyond which an individual in

movement is considered a visitor. This concept is somewhat intrinsically vague, especially in relation to

domestic tourism, and, partly as a consequence of this, an accepted international standard defining it with

sufficient precision has not yet been developed.

In Italy there are two main sources addressing tourism from the demand side. The first is a survey on

international travellers (foreigners in Italy and Italians abroad) conducted by the Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi

(UIC), carried out at the Italian borders through face to face interviews 7. Being the main purpose of the

survey the estimation of the Travel item of the balance of payments, expenditure is its target variable. The

survey definition of travellers refers to any individual resident8 in a given country moving to another country,

irrespective of the purpose of the trip and the length of the stay. Hence, any traveller physically crossing the

national borders is covered by the survey (i.e. travellers crossing the borders commuting to reach their usual

work location are also included). The expenditures measured in this survey are all those performed by the

traveller while visiting the foreign country, provided that they are carried out to acquire goods and services

for personal use.

7 For further details on the survey methodology see: Biagioli, A. (1997), “Sample Survey on Italian International Tourism”, in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Third International Forum on Tourism Statistics, Paris; Eurostat (2000), Technical Group Travel Report. Revision of the Collection Systems for the Travel item of the Balance of Payments of EU Member States Following Stage Three of the EMU , Luxembourg; Mirto, A. P. and Ortolani, G. G. (1998), Methodology for The Collection of Statistics on Tourist Movements at Land Frontiers, Seminar “Frontier Statistics in European Countries” (World Tourism Organization), Madrid; Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1996), Indagine campionaria sul turismo internazionale dell’Italia. Luglio. Agosto, Settembre 1995, Roma; World Tourism Organisation (1999), Seminar on Frontier Statistics in European Countries (Surveys on Inbound & Outbound Tourism), Madrid and UIC's web site at http://www.uic.it.8 The concept of 'residence' of an individual is also defined in BPM5. It broadly identifies the country (economy) in which that individual has his/her 'centre of economic interest'; in most cases, it is the country where the individual normally lives.

6

The second source is a household telephone survey conducted by ISTAT9 on "Trips and vacations" ("Viaggi

e Vacanze") of Italians. This survey provides figures on the number of trips and the number of night stays of

Italians, but it does not provide data on expenditure. The scope of the ISTAT survey is more restricted than

that of the UIC survey, as the former only covers tourists (i.e. the visitors who spent at least one night outside

the usual environment). In addition, consistently with tourism statistics definitions, travellers commuting to

reach their usual work location are excluded.

In this study an attempt has been made to estimate the inbound and domestic expenditure in Italy, or total

internal tourism expenditure, disaggregated by region, merging the two sources described above. To this

end, a certain degree of approximation in the compliance to definitions was unavoidable, given the current

data availability. Travellers, in this note, are defined as those spending at least one night outside their usual

residence, therefore excluding all the so called same-day visitors or excursionists (those starting and ending

the trip in the same day), which, in principle should have been also included. The limitation of the population

of travellers to tourists might seem quite restrictive, as same-day visitors can sometimes generate an

important part of tourist expenditure. However, it should be also considered that excursionists, although very

numerous, are normally far less important in terms of per capita expenditure. According to the UIC data

(referring only to foreign travellers) in the border regions of Northern Italy the share of same-day travellers

on total travellers is 44%, but their expenditure represents only 7.5% of the total10. This suggests that the

impact of this exclusion should not substantially bias the results of this study.

It is also underlined that a concept of "consumption during the trip" is used here. Only goods and services

acquired by the traveller during the stay are considered11. Goods and services acquired at home are excluded,

even when the acquisition is clearly related to the trip (i.e. the suitcase bought before the journey). The

reason for the adoption of this approach comes from the fact that expenditure data are only derived from the

UIC survey, which strictly applies this concept, in line with b.o.p. rules.

The quantification of the expenditure of resident visitors within Italy's territory (domestic tourism

expenditure) poses serious problems due to the unavailability of official statistics directly addressing this

area. However, from the ISTAT survey on "Trips and vacations" it is possible to derive a comprehensive

assessment on the number of night stays that Italians spent outside their usual residence. Table 2.1 shows the

survey results on the year 2002, with figures broken down by destination region, type of accommodation

(hotel, rented dwelling, accommodation offered by friends or relatives, other) and purpose of travel

(personal, business).

9 ISTAT (2002), I viaggi in Italia e all'estero nel 2001, Roma; available at http://www.istat.it.10 This percentage exclude the expenditure of same-day travellers for shopping reasons as this is a quite peculiar phenomenon mainly due to Slovenian and Croatian residents shopping in the Friuli region.11 Those goods and services are included irrespective of the fact that the are paid before, during or after the trip. For example, aggregates presented in this paper include accommodation services both paid directly at the hotel and paid in advance through a travel agency.

7

The quantity of nights spent outside the usual environment is certainly highly correlated with the level of

travellers' expenditure. Indeed, total expenditure can be defined as the product between the number of nights

and the average per night expenditure or average daily per capita expenditure. Information on the latter

quantity is at present not available in Italy's official statistics. In this study an attempt is made to estimate it,

with an acceptable approximation, using the results of the UIC survey on the expenditure of foreign

travellers.

In order to improve the comparability of average expenditure between Italian and foreign travellers, only

visitors from other euro area countries have been considered in the second group; this allowed, for example,

to exclude foreign tourists from certain countries (i.e. the US and Japan) that most likely are characterised by

an expenditure behaviour significantly different from that of Italians. Euro area travellers have been further

classified according to the region visited, the purpose of travel (personal, business) and the type of

accommodation used (hotel, other accommodation), since these three variables show a clear correlation with

the average expenditure per night.

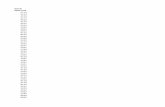

Table 2.1 - Domestic tourism. Night stays. Thousands. 2002.(1)

Personal Business TOTALOf which

hotelOf which

hotelPIEMONTE 14,243 3,355 1,505 903 15,748VALLE D'AOSTA 6,693 2,419 124 74 6,817LIGURIA 36,002 8,730 736 442 36,738LOMBARDIA 36,039 5,123 5,557 3,334 41,596TRENTINO ALTO ADIGE 24,127 12,012 760 456 24,887VENETO 30,405 7,287 3,619 2,171 34,024FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA 6,923 1,153 1,384 830 8,307EMILIA ROMAGNA 40,422 21,850 4,061 2,437 44,483TOSCANA 41,207 9,020 2,500 1,500 43,707UMBRIA 7,607 3,284 560 336 8,167MARCHE 18,292 1,737 2,610 1,566 20,902LAZIO 33,457 4,010 6,551 3,931 40,008ABRUZZI 15,630 4,896 908 545 16,538MOLISE 2,604 575 301 181 2,905CAMPANIA 31,131 5,631 944 566 32,075PUGLIA 42,693 3,966 1,892 1,135 44,585BASILICATA 4,943 756 389 233 5,332CALABRIA 39,352 2,073 1,135 681 40,487SICILIA 46,063 5,203 2,518 1,511 48,581SARDEGNA 37,156 5,558 2,755 1,653 39,911

ITALY 514,989 108,638 40,809 24,485 555,798

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON ISTAT DATA(1) The table shows the crossing of three variables: destination region, type of accommodation and purpose of travel. Istat provided regional data broken down by type of accommodation and, separately, by purpose of travel, and national data jointly crossed by accommodation and purpose. In order to cross the mentioned three variables, a national average share of the night stays of business travellers spent in hotels on total night stays in hotels has been estimated (60%). This percentage has been applied to the night stays in hotels in each region, in order to estimate the hotel share for the business segment. The nights spent in hotel by personal travellers have been calculated as the difference between total night stays in hotels and night stays in hotels of business travellers previously estimated.

8

Despite the remarkable dimension of the sample (35,202 interviews), the crossing of these three variables

produced a few cells with a rather small sample dimension. For cells with less than 30 underlying interviews,

the sample values have been substituted by the global average. In order to improve the robustness of the

estimated averages, an outlier detection and correction phase has been subsequently performed. The results

of this elaboration are shown in Table 2.2.

The resulting average expenditure per night, although referred to foreign travellers, contains elements of

homogeneity that make it, in our opinion, a good proxy of the expenditure of the Italians travelling

domestically. It seems in fact reasonable that an inbound visitor from the euro area and a domestic visitor

that visit the same Italian region, in a similar type of accommodation and for similar purposes might have

spent, on average, a comparably similar amount of money per day. In practice, the number of nights spent

outside the usual environment by each category of Italian travellers (Table 2.1) has been multiplied by the

average expenditure of the corresponding category (Table 2.2), providing an estimation of the total domestic

expenditure of Italian travellers.

Table 2.2 - Inbound tourism. Average expenditure per night of euro area travellers(1)(2). Euro. 2002.

Personal Business

HotelOther

accommodation HotelOther

accommodationPIEMONTE 121 45 159 31VALLE D'AOSTA 149 37 226 57LIGURIA 86 38 121 57LOMBARDIA 113 38 188 57TRENTINO ALTO ADIGE 77 36 116 28VENETO 101 41 158 52FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA 111 46 127 90EMILIA ROMAGNA 77 32 148 54TOSCANA 100 52 142 42UMBRIA 104 36 166 43MARCHE 76 26 140 67LAZIO 135 39 238 46ABRUZZI 85 30 186 36MOLISE 45 18 77 20CAMPANIA 106 38 159 46PUGLIA 95 32 153 64BASILICATA 81 32 138 35CALABRIA 81 29 135 34SICILIA 103 44 150 45SARDEGNA 99 35 153 39

ITALY 99 40 168 43

SOURCE: UIC(1) Excluding same-day visitors.(2) Grey cells indicate imputed values.

Data on non resident visitors' expenditure in Italy (inbound tourism expenditure) have been derived directly

from the UIC survey on international tourism. Differently from the concepts used by the UIC for b.o.p.

purposes, the definition of traveller considered in this paper is more restrictive, as all "same-day travellers"

have been excluded as well as commuting travellers. The latter have been identified on the basis of the

residence of the employer: individuals moving to the location of the employer have been considered as

9

commuting travellers12. As far as the expenditure is concerned, consistently with b.o.p. practices, only the

"consumption during the trip" is considered (see above).

Finally, combining domestic and inbound tourism expenditure, a comprehensive picture of total internal

tourism expenditure in Italian regions has been produced. Table 2.3 shows the results, with a split between

personal and business purposes. The subsequent paragraph provides a more detailed analysis of the

characteristics of Italy's internal tourism, as derived from the estimation procedure explained above.

Table 2.3 - Domestic, inbound and total (internal) tourism expenditure(1). Euro millions. 2002.

Domestic expenditure Inbound expenditure Internal expenditurePersonal purpose

Business purpose

Total Personal purpose

Business purpose

Total Personal purpose

Business purpose

Total

PIEMONTE 892 163 1,055 648 338 986 1,540 501 2,041VALLE D'AOSTA 522 20 541 115 9 125 637 29 666LIGURIA 1,799 70 1,869 700 128 828 2,499 198 2,697LOMBARDIA 1,757 754 2,511 1,916 1,770 3,686 3,673 2,524 6,197TRENTINO ALTO ADIGE 1,352 61 1,413 994 119 1,113 2,346 180 2,526VENETO 1,678 417 2,096 3,747 505 4,252 5,426 922 6,348FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA 393 155 548 702 107 809 1,095 263 1,358EMILIA ROMAGNA 2,276 449 2,725 1,057 414 1,471 3,334 863 4,196TOSCANA 2,572 255 2,828 3,278 453 3,731 5,851 708 6,559UMBRIA 496 65 561 299 38 337 794 103 898MARCHE 568 288 856 227 48 275 795 336 1,131LAZIO 1,684 1,057 2,741 2,570 1,120 3,690 4,254 2,177 6,431ABRUZZI 731 115 845 173 43 215 903 157 1,061MOLISE 63 16 79 14 6 20 77 22 99CAMPANIA 1,566 108 1,673 1,095 185 1,280 2,661 293 2,953PUGLIA 1,613 223 1,836 367 43 410 1,981 266 2,246BASILICATA 197 38 234 49 9 58 246 46 292CALABRIA 1,241 108 1,349 238 11 249 1,479 118 1,597SICILIA 2,348 273 2,621 718 60 778 3,066 333 3,399SARDEGNA 1,650 296 1,946 400 54 455 2,050 351 2,401ITALY 25,397 4,931 30,327 19,310 5,458 24,768 44,706 10,389 55,095

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON UIC AND ISTAT DATA

(1) Excluding same-day visitors.

3. Main features of Italy's internal tourism expenditure patterns

The estimation method previously described allowed to derive a data set on Italy's internal tourism, based on

UIC's survey results for the inbound side and on estimates - original contribute of this paper - on ISTAT data

for the domestic side. This paragraph analyses this data set in order to attempt to outline the main

characteristics of Italian regions' total tourism demand, both from the physical (number of night stays) and

monetary (expenditure) standpoint, highlighting its geographic variability. Italy's regional tourism data are

broken down by the main tourism classification variables, in order to shed light on features that could remain

hidden if only a global perspective was adopted.

12 In this way, commuting travellers are distinguished from 'standard' business travellers, as the latter travel to a location which is different from the location of the employer.

10

In 2002, € 55,095 millions were spent by travellers, in trips consisting of about 887 millions of night stays.

The phenomenon is not uniformly distributed in Italian areas or region. As it can be seen in Table 3.1, the

Centre is the area with the highest total expenditure (15,018 € millions), whereas the South is at the top by

number of night stays (about 288 millions).

Table 3.1 - Domestic, inbound and total (internal) tourism expenditure (Euro millions) and night stays (thousands) by Italian region visited. Excluding same-day visitors. 2002.

DOMESTIC INBOUND TOTALexpenditure night stays expenditure night stays expenditure night stays

PIEMONTE 1,055 15,748 986 14,883 2,041 30,631VALLE D'AOSTA 541 6,817 125 1,605 666 8,422LIGURIA 1,869 36,738 828 12,950 2,697 49,688LOMBARDIA 2,511 41,596 3,686 39,302 6,197 80,898

NORTH-WEST 5,976 100,899 5,625 68,740 11,602 169,639TRENTINO ALTO ADIGE 1,413 24,887 1,113 18,956 2,526 43,843VENETO 2,096 34,024 4,252 56,820 6,348 90,844FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA 548 8,307 809 12,113 1,358 20,420EMILIA ROMAGNA 2,725 44,483 1,471 23,178 4,196 67,661

NORTH-EAST 6,781 111,701 7,646 111,067 14,427 222,768TOSCANA 2,828 43,707 3,731 46,597 6,559 90,304UMBRIA 561 8,167 337 5,495 898 13,662MARCHE 856 20,902 275 5,918 1,131 26,820LAZIO 2,741 40,008 3,690 36,671 6,431 76,679

CENTRE 6,986 112,784 8,032 94,680 15,018 207,464ABRUZZI 845 16,538 215 4,486 1,061 21,024MOLISE 79 2,905 20 586 99 3,491CAMPANIA 1,673 32,075 1,280 15,718 2,953 47,793PUGLIA 1,836 44,585 410 9,808 2,246 54,393BASILICATA 234 5,332 58 909 292 6,241CALABRIA 1,349 40,487 249 6,088 1,597 46,575SICILIA 2,621 48,581 778 10,809 3,399 59,390SARDEGNA 1,946 39,911 455 9,065 2,401 48,976

SOUTH AND ISLES 10,584 230,414 3,464 57,469 14,048 287,883ITALY 30,327 555,798 24,768 331,956 55,095 887,754

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON UIC AND ISTAT DATA

These data reflect different behaviours as for the composition of the flows: domestic tourism is mainly

addressed to southern regions, while international tourism tends to be concentrated in the central and north-

eastern part of the country. Since international tourism is a segment richer than domestic tourism, southern

regions present a lower daily average expenditure. In the following an attempt is made to provide some

suggestions about the main factors that could describe the specificities of the various regions.

As regards the purpose of trip, Figure 3.1 shows that in Italy 91% of night stays is made by leisure tourists

and 9% by business tourists, whereas the composition of total expenditure in Italy shows a significantly

different concentration: only 81% is spent by tourists travelling for personal purposes and 19% by business

tourists.

The different composition between night stays and expenditure implies a different daily per-capita

expenditure for the two segments: as shown in Figure 3.2, the value for the whole country is 126 € for

11

business travellers and 56 € for personal purposes. This quite large difference seems to depend on the

relative importance of business tourism inside the regions.

Figure 3.1 - Internal tourism. Composition of night stays and expenditure in Italy, by purpose of the trip. Excluding same-day visitors. 2002.

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON UIC AND ISTAT DATA

Figure 3.2 - Internal tourism. Daily per-capita expenditure (euro) by region and purpose of the trip. Excluding same-day visitors. 2002.

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON UIC AND ISTAT DATA

Actually, the difference is particularly high in Lombardia and Lazio, where business tourism represents

nearly 20% of the night stays while it is very limited in regions presenting a structure of tourism with

prevalence of personal purposes.

The purpose of the trip seems to be the classification attribute that better explains the differences among the

travellers' behaviours. In other words, a series of attributes is usually associated to each specific trip purpose

12

(e.g. business travellers prefer to stay in hotel, usually they go to particular regions and come from particular

countries, etc.).

Another important - but often associated to the purpose of the trip - source of variability for travellers'

behaviour in the Italian regions is the type of accommodation chosen. As it is evident in Table 3.2 below, the

higher is the share of travellers staying in hotels, the higher will be their average expenses. Non-hotel

hospitality is largely used (76% of the night stays), with peaks in the southern regions (Calabria 93%, Puglia

89%), while the north-eastern regions Emilia Romagna and Trentino Alto Adige present the lowest values

(respectively 45% and 50%). Molise presents the lowest daily expenditure (only 27 € per-capita); Valle

d'Aosta, with 79 €, is on the other side, especially because of quite high expenditure at hotels (152 €).

Table 3.2 - Internal tourism. Daily per-capita expenditure (euro) and night stays (percentage on the total) by region and type of accommodation. Excluding same-day visitors. 2002.

Daily per-capita expenditure Night staysHotel Other Global Hotel Other

PIEMONTE 129 44 67 27.0% 73.0%VALLE D'AOSTA 152 38 79 36.6% 63.4%LIGURIA 88 39 51 25.0% 75.0%LOMBARDIA 142 39 60 20.3% 79.7%

NORTH-WEST 121 40 59 24.2% 75.8%TRENTINO ALTO ADIGE 78 35 57 50.1% 49.9%VENETO 114 41 62 27.8% 72.2%FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA 118 50 66 23.9% 76.1%EMILIA ROMAGNA 84 34 61 54.6% 45.4%

NORTH-EAST 90 39 61 43.1% 56.9%TOSCANA 106 52 65 24.1% 75.9%UMBRIA 110 36 68 44.3% 55.7%MARCHE 106 29 41 15.8% 84.2%LAZIO 186 39 68 19.8% 80.2%

CENTRE 131 42 62 22.5% 77.5%ABRUZZI 95 30 51 32.9% 67.1%MOLISE 53 18 27 26.0% 74.0%CAMPANIA 111 38 52 19.3% 80.7%PUGLIA 108 33 41 11.4% 88.6%BASILICATA 94 32 44 18.5% 81.5%CALABRIA 94 29 33 6.8% 93.2%SICILIA 113 44 54 13.8% 86.2%SARDEGNA 111 35 49 18.1% 81.9%

SOUTH AND ISLES 106 35 46 15.3% 84.7%ITALY 107 38 55 24.0% 76.0%

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON UIC AND ISTAT DATA

Data are rather variable and indicate that the level of expenditure is strictly correlated with the

accommodation chosen. In this sub-analysis, the overnight stay in hotel is representative of a sort of "upper-

class" tourism - often associated with business tourism - opposed to the tourism of the travellers staying in

alternative accommodation. As for the latter, the use of "second homes" for Italian travellers is particularly

important for most of the Italian regions. Travellers adopting this type of accommodation usually yield a

limited economic impact on the visited regions accompanied by a relevant (increasing) negative effect on

their environment, causing in some case problems of "tourism sustainability".

13

The country of origin of the travellers heavily influences their behavioural pattern. Several factors, such as

the socio-economic profile of travellers, the purpose of the trip and the distance from the Italian region

visited, seem to affect the length of the stay and the expenditure pattern. Table 3.3 below shows how

geographical factors affect the daily per-capita expenditure. The average daily per-capita expenditure is 75 €,

but there is a strong variability depending on the region visited and the country of residence of the traveller:

Centre regions present the highest daily per-capita expenditure (85 €), followed by North-West (82), North-

East (69) and South and Isles (60). Again, the role of business tourism appears to be fundamental: the highest

share of business travellers is concentrated - as it was already mentioned - in Centre and North-West regions.

Looking at the tourists' country of origin, the Japanese are the top daily per-capita spenders (160 €), followed

by the travellers from the United States, Russia and the United Kingdom. On the opposite side, Germans,

Italians and Greeks showed the lowest level of expenditure - respectively 60, 59 and 37 euro. In general,

compared to international tourism, domestic tourism is characterised by a lower daily per capita expenditure.

Table 3.3 - Internal tourism. Daily per capita expenditure (euro) by destination area and country of residence. Excluding same-day visitors. 2002.

North-West North-East Centre South And Isles TotalITALY 59 61 62 46 59JAPAN 213 141 148 146 163UNITED STATES 169 136 131 131 139RUSSIA 154 137 96 101 119UNITED KINGDOM 111 101 117 107 110CROATIA 109 78 117 141 90AUSTRIA 85 75 75 63 74FRANCE 68 83 81 55 73SWITZERLAND 70 74 85 59 71SPAIN 70 73 66 69 69THE NETHERLANDS 80 51 73 66 66BELGIUM 91 55 82 43 65GERMANY 63 58 63 50 60GREECE 67 47 45 29 37OTHER-EUROPEAN 60 52 66 66 60OTHER-NON EUROPEAN 99 97 104 96 101TOTAL 82 69 85 60 75

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON UIC AND ISTAT DATA

4. Tourism attractiveness of Italian regions

In paragraph 2 the total internal tourism expenditure in each Italian region has been determined. We will try

now to answer the question on whether the amount of this expenditure is adequate in relation to certain

'quality' aspects of the tourist supply, summarised by an indicator that is defined as attractiveness of the

region. In defining the concept of attractiveness, the presence of tourist infrastructure (i.e. hotels, airports,

highways, etc.) has been deliberately excluded, as we aim at defining a concept of pure tourist potentiality, in

order to highlight to which extent regions manage to exploit their tourist resources. In other words, making a

14

parallel with a commercial product, there can be qualities that are intrinsic to the product, while other

qualities, such as accessibility and name (standing, reputation, etc.), are the effect of promotion activities and

other investments aiming at the product valorisation. The objective of this analysis is to try to 'quantify' the

former type of qualities, i.e. the intrinsic ones, for each Italian region.

Is it possible to assess the attractiveness of a region in the terms described above? There is certainly a strong

component of subjectivity in evaluating how attractive a destination is for a traveller. In addition, previous

paragraphs have shown that people travel for different purposes (i.e. vacation or business), each

characterised by different attracting factors.

The Touring Club Italiano (TCI), in the mentioned study in which the approach was first introduced 13, has

proposed three types of attractiveness indicators for the Italian regions which can be very helpful for the

purposes of this study. The first indicator, the cultural attractiveness indicator, is based on an inventory of

cultural and art assets (such as churches, historical buildings, castles, museums, archaeological sites, etc.),

weighted by their importance. The second, the environmental attractiveness indicator, is based on a number

of indices which aim at the overall evaluation of the quality of the environment, such as percentage of parks

and protected areas, presence of natural assets (beaches, lakes, mountains, etc.), quality of the water,

pollution, opinion surveys, weighted by the dimensions of the region. The third indicator, the social

attractiveness indicator, measures the intensity of the offer of social activities and events such as religious

celebrations, historical representations, gastronomic fairs, etc.

The three indicators address three characteristics of the tourism supply (culture, nature and society) which

might be seen as strong "triggers" of travellers expenditure. Indeed, according to the 2002 answers to the

question on the main purpose of the trip in the UIC survey, about 65% of the expenditure of foreign

travellers in Italy can be connected with one of those three aspects (33% for cultural, 27% for environmental

and 5% for social reasons).

Still according to the UIC survey, the rest of the expenditure is connected with trips for visits to friends and

relatives (15%) and with business purposes (20%). For these types of travellers it has been assumed that two

simple indexes can be considered as attractiveness indicator. For visits to friends and relatives the index

chosen has been the visited regions' total population, following the neutral assumption that these trips could

be approximately proportional to the number of inhabitants. For business trips, the GDP in services of the

region is the chosen indicator, under the assumption that the level of economic activity in services is the

main trigger in this case. The underlying idea is that the dimension of the business travel market is positively

correlated with the degree of development of the destination (and also origin) economies, and, consequently,

with the size of the services sector14.

13 Touring Club Italiano - Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1998) and Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1998).14 See Littlejohn, D. (2001), "Business Travel Markets: New Paradigms, New Information Needs?" in Lennon, J. John ed., Tourism Statistics. International Perspectives and Current Issues, London.

15

The hypothesis formulated in this work is that each of the five attractiveness indicator signals the potentiality

of each region to capture tourism in each particular market segment. This allows reaching the final objective

of obtaining an overall attractiveness indicator, built as the weighted average of the five indicators. The

weights used are the shares of each type of tourism in total inbound expenditure, derived from the UIC

survey (Table 4.1). The indicators value are shown in Table 4.2.

Table 4.1 - Weights used to aggregate the attractiveness indicators. Percentages.

Personal purposesBusiness

purposesHolidays Visits to relatives

and friendsCulture Nature Society

33% 27% 5% 16% 19%

SOURCE: UIC

Table 4.2 - Attractiveness indicator by Italian region. Index (Italy = 1000).

Overall indicator

TCI culture

TCI nature(1)

TCI society

Population GDP services

PIEMONTE 56 20 80 27 74 78VALLE D'AOSTA 14 24 12 32 2 3LIGURIA 42 62 17 117 27 33LOMBARDIA 99 49 77 37 159 184TRENTINO ALTO ADIGE 26 12 51 33 17 23VENETO 74 78 58 75 80 83FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA 29 31 26 74 21 22EMILIA ROMAGNA 67 54 71 71 70 80TOSCANA 82 107 75 85 61 67UMBRIA 47 91 29 86 15 14MARCHE 40 54 33 85 26 24LAZIO 103 151 50 53 90 122ABRUZZI 28 26 41 23 22 18MOLISE 11 13 16 21 6 5CAMPANIA 75 97 44 37 100 73PUGLIA 55 46 64 43 70 48BASILICATA 17 12 36 11 10 8CALABRIA 30 13 54 27 35 25SICILIA 70 56 85 43 87 66SARDEGNA 35 7 83 21 29 23

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON TOURING CLUB ITALIANO DATA

(1) The nature indicator originally developed by TCI was a relative index, which did not take into account the dimension of the region. For this reason it has been scaled using the dimension (in km2) of the region.

The estimated internal tourism expenditure, in 2002 and the attractiveness indicator can now be put in

relation, in order to assess the degree of exploitation of the tourism potential of each region. The latter

variable is calculated as a ratio between the first two variables. Consequently, it expresses the amount of

internal tourism expenditure 'stimulated' by each point of attractiveness. Table 4.2 shows the levels of the

three variables in each region.

16

The regions with a higher expenditure per point are those in which the tourist product is well valorised, while

regions with a low value do not exploit it in an optimal way. The region with the best capability of

valorisation is Trentino Alto Adige with euro 95.4 millions for each attractiveness point, but also Veneto

(86.1) and Toscana (79.8) show a good exploitation level.

Table 4.2 - Exploitation of tourist potential. Euro millions, index, euro millions per point. 2003.

Internal tourism expenditure(1) Attractiveness Degree of exploitation

PIEMONTE 2,041 56 36.5VALLE D'AOSTA 666 14 49.0LIGURIA 2,697 42 64.9LOMBARDIA 6,197 99 62.5TRENTINO ALTO ADIGE 2,526 26 95.4VENETO 6,348 74 86.1FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA 1,358 29 47.5EMILIA ROMAGNA 4,196 67 62.7TOSCANA 6,559 82 79.8UMBRIA 898 47 19.0MARCHE 1,131 40 28.6LAZIO 6,431 103 62.2ABRUZZI 1,061 28 38.2MOLISE 99 11 8.8CAMPANIA 2,953 75 39.2PUGLIA 2,246 55 40.9BASILICATA 292 17 16.8CALABRIA 1,597 30 52.4SICILIA 3,399 70 48.6SARDEGNA 2,401 35 69.2

ITALY 55,095 1,000 55.1

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON TOURING CLUB ITALIANO DATA

(1) Excluding same-day visitors.

It is interesting to notice that a better utilisation of tourist resources seems to occur in the regions with a

stronger economic development, as to indicate a certain link between the two phenomena. This relation is

shown in Figure 4.1, where the tourist exploitation ratio has been plotted against the per-capita GDP of the

regions, taken as an indicator of economic development.

17

Figure 4.1 - Plot of Italian regions' degree of exploitation of tourism potential against economic development.

SOURCE: UIC ELABORATION ON UIC AND TOURING CLUB ITALIANO DATA

While the presence of a certain correlation is rather clear, the direction of the cause-effect link can not be

easily identified. Is the economic development of the region that determines the regions' capability to

valorise its tourism resources? Or is rather the tourist valorisation of the area that promotes economic

wealth? The first hypothesis seems to be plausible, as it can be argued that the economic development of the

region certainly creates a favourable background for the development of tourism. For instance, investments

in infrastructures for the tourism industry (accommodations, transport connections, promotion activities, etc.)

can be more easily undertaken in wealthy regions.

Nevertheless, the second hypothesis cannot be disregarded. It could be argued, for example, that a proper

valorisation of tourism in the South of Italy has always been problematic, for geographical15 and other

reasons. This is likely to have contributed, at least partially, to the economic underdevelopment of those

regions.

15 Indeed, the geographic accessibility of the regions has been disregarded in the evaluation of attractiveness, while it could play an important role: the easier, or cheaper, the region is to reach, the higher are the probability of attracting tourists.

18

5. Tourism and regional development

Following the hypothesis that tourism can provide important impulse on economic development, we try an

approximate quantification of the short-term impact of tourist consumption on regional economies, in terms

of GDP and employment. On this respect, we rely on a study of CISET16, which has developed regional

activation matrices for tourist expenditure. These matrices allow calculating the impact on GDP and

employment of aggregate tourist expenditure variations. CISET estimated that, as an average for the whole

Italian economy, each EUR million of tourist expenditure activates about 0.8 EUR million of value added

and 28 employees. These results include the so-called direct and indirect effects, where the former stem from

the economic activities directly getting in contact with the tourist, while the latter originate from the

subsequent steps of the production chain17.

The CISET matrices also estimate the regional dispersion of the value added activation. In fact, not all the

activated value added is created in the region where tourism activities actually occur, as indirect effects can

stimulate production in other regions. This dispersion effect is geographically differentiated. It is more

evident in the regions with a weaker productive structure, which, consequently, are more dependent on the

supply of other regions, as it is the case of the regions of the South of Italy.

Through this informative tool we simulate a hypothesis of increase of tourist expenditure in the regions

where some unexploited potential has been detected. It could, for instance, be assumed that all regions, in a

somewhat ideal scenario, manage to valorise their traveller attractiveness up to the national average (as

mentioned, 55.1 EUR million for each attractiveness point), as shown in Table 5.1.

It is interesting to notice that this ideal activation in some cases hits the constraint of the labour force

available in the region, under the assumption that there is no inter-regional labour mobility. Some of the

regions with a potential improvement in tourism activity are in a situation of "full employment" or very low

unemployment rate, which could clearly limit the possible development. As an example, in the region of

Marche the current unemployment rate is 3.7%. The supposed activation tourist expenditure (euro 1,047

millions for Marche) would require around 17,000 new employees, representing 2.6% of Marche's labour

force. In general, it is not plausible that the employment rate might be below a certain threshold that is

normally considered as a frictional or physiological rate. Therefore, whenever the unemployment rate of the

region is rather low, we assume that a limit exists to the development of tourist activity, given by the

availability of local human resources.

16 Manente, M., "Il turismo nell'economia italiana" in Becheri, E. et al. (2003), XII Rapporto sul turismo italiano, Firenze.17 See Costa, P. and Manente, M. (2000), Economia del turismo, Milano.

19

Table 5.1 - Activation of tourism resources.

Current situation Activation

Tourist expenditure (Euro millions)

GDP (Euro millions)

Unemployment rate (% of labour force)

New tourist expenditure

(Euro millions)

Increase in GDP

(%)

Increase in employees

(units)

Increase in employees

(% of labour force)

PIEMONTE 2,041 96,010 4.8% 1,041.6 0.5% 14,517 0.8%VALLE D'AOSTA 666 2,791 3.4% 83.0 1.8% 1,685 2.9%LIGURIA 2,697 32,899 6.0% 0.4% 4,294 0.6%LOMBARDIA 6,197 227,998 3.6% 0.3% 21,481 0.5%TRENTINO 2,526 25,345 2.5% 0.4% 3,590 0.8%VENETO 6,348 103,951 3.4% 0.3% 9,932 0.5%FRIULI GIULIA 1,358 25,393 3.8% 216.7 0.8% 7,030 1.3%EMILIA ROMAGNA 4,196 98,942 3.1% 0.4% 13,893 0.7%TOSCANA 6,559 76,153 4.7% 0.4% 10,868 0.7%UMBRIA 898 16,066 5.2% 1,700.8 3.0% 16,019 4.6%MARCHE 1,131 29,218 3.7% 1,046.8 1.8% 16,929 2.6%LAZIO 6,431 115,343 8.7% 0.4% 14,918 0.7%ABRUZZI 1,061 21,017 5.3% 470.0 1.6% 10,768 2.1%MOLISE 99 5,074 12.9% 521.4 3.8% 6,394 5.2%CAMPANIA 2,953 74,178 20.2% 1,196.2 1.2% 29,364 1.4%PUGLIA 2,246 51,918 13.8% 780.1 1.2% 21,209 1.5%BASILICATA 292 8,734 16.1% 667.0 2.1% 6,083 2.8%CALABRIA 1,597 25,040 23.5% 82.6 0.5% 4,395 0.6%SICILIA 3,399 64,816 20.1% 456.7 0.6% 13,610 0.8%SARDEGNA 2,401 23,781 16.8% 0.4% 2,919 0.4%ITALY 55,095 1,124,666 8.7% 8,262.9 0.6% 229,897 1.0%

SOURCE: UIC AND ISTAT

Taking into account the limitation of the labour factor, we modify the initial hypothesis of activation,

simulating an increase of expenditure only in those regions with both an unexploited tourism potential and a

high unemployment rate (higher than 10%), highlighted with an ellipse in figure 5.1. The regions included in

this group are exclusively in the southern part of the country. Abruzzi and Sardegna are the only two

southern regions not complying with the mentioned two criteria because of, respectively, a low

unemployment rate and a degree of exploitation of the tourism potential slightly higher than the national

average.

20

Figure 5.1 - Plot of Italian regions' degree of exploitation of tourism potential against unemployment rate.

We now formulate again the hypothesis that the tourism demand is increased up to the national average

exploitation (euro 55.1 millions per attractiveness point), but only for the six regions identified as capable to

supply the local labour force that would be needed. In figure 5.2 the resulting unemployment rate reduction

is shown. The stronger benefits would be obtained by those regions with a lower current tourist expenditure

such as Molise (from 12.9% to 8.1%) and Basilicata (from 16.1% to 13.5%). Regions that presently show a

better capability of valorisation of tourism would obtain less significant benefits (i.e. Calabria and Sicilia).

Figure 5.2 - Plot of Italian regions' degree of exploitation of tourism potential against unemployment rate, present and in the ideal scenario.

21

Regions with activationpotential

6. Concluding remarks

The analysis has showed that Italian regions are clearly diversified as regards their pure tourist potential or

attractiveness, i.e. the intrinsic qualities of the product (the destination) they offer in the - increasingly

competitive - international and domestic markets.

Also different from one region to the other is the degree of exploitation of that tourist potential. Some

regions appear to be successful in adding extra-value to the 'basic' region attractiveness, by improving the

accessibility and the image of their tourist products, by means of appropriate investments or the efficient

allocation / combination of the available resources. Symmetrically, it seems that other regions have

substantially failed to exploit their potential to attract visitors. This is the case of most Italy's Southern

regions.

But the study has pointed out that the regions of the South of Italy are of the utmost relevance because of an

additional element. These destinations are characterised by a structurally large unemployment rate.

Consequently, the expansion of tourist demand that the ideal scenario would imply could be theoretically

satisfied by the local offer of unemployed labour force.

Hence, the study confirms and qualifies, in relation to the scope of internal tourism, what a previous work, in

Touring Club Italiano - Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1998), found in the more restricted area of inbound

tourism. The relevance of the policy-making issue of a strengthening of the promotion of tourism in Italy's

Mezzogiorno is then reinforced.

As mentioned in the introduction, it is not the ambition of the analysis to be conclusive, as it could be

improved in many respects. We stress here that the study would very much gain solidity from the

improvement in data sources, particularly with the substitution of the estimated figures on domestic tourism

expenditure with official data. The latter might hopefully be available in the next few years, as this

information is indispensable for the development of the country's Tourism Satellite Account.

Moreover, a possible direction for improvement would be the consideration of certain trans-regional effects

that are disregarded in this paper. The increase of tourism consumption in one region can be detrimental for

other competitor regions, as domestic tourists can be diverted from one Italian region to another. When this

occurs, the benefits tend to cancel out at a national level. A net benefit for the country as a whole can

however be achieved in many ways, as, for instance, capturing foreign international travellers from non-

Italian destinations, diverting Italian travellers from foreign to domestic destinations or prompting new

tourism demand.

Finally, it should also be considered that, even in an ideal scenario, tourism development can bring negative

effects. A strong and rapid growth of tourism, even disregarding the relevant negative implications for the

socio-cultural dimension (modifications of the destinations' system of values, life-styles, traditions, etc.), can

22

have a harmful impact for the mere economic sphere. One of the worst dangers that is usually mentioned is

the so called crowding out process, which occurs, in a given destination, when the non-tourist economic

activities tend to disappear because the tourism sector attracts all the available resources 18, with a tendency

towards a mono-sectoral economy that certainly involves problem of sustainability.

7. References

Becheri, E. et al. (2003), Rapporto sul turismo italiano, Firenze

Biagioli, A. (1997), “Sample Survey on Italian International Tourism”, in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Third International Forum on Tourism Statistics, Paris

Costa, P. and Manente, M. (2000), Economia del turismo, Milano

Eurostat (2000), Technical Group Travel Report. Revision of the Collection Systems for the Travel item of the Balance of Payments of EU Member States Following Stage Three of the EMU, Luxembourg

Eurostat, European Implementation Manual on Tourism Satellite Accounts, 2002, Luxembourg

European Commission, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, World Tourism Organization, United Nations (2001), Tourism Satellite Accounts: Recommended Methodological Framework. Luxembourg - Paris - Madrid - New York

International Monetary Fund (1993), Balance of Payments Manual - Fifth Edition, Washington DC

ISTAT (2002), I viaggi in Italia e all'estero nel 2001, Roma

Littlejohn, D. (2001), "Business Travel Markets: New Paradigms, New Information Needs?" in Lennon, J. John ed., Tourism Statistics. International Perspectives and Current Issues, London

Manente, M., "Il turismo nell'economia italiana" in Becheri, E. et al. (2003), XII Rapporto sul turismo italiano, Firenze.

Mirto, A. P. and Ortolani, G. G. (1998), Methodology for The Collection of Statistics on Tourist Movements at Land Frontiers, Seminar “Frontier Statistics in European Countries” (World Tourism Organization), Madrid

Prud'homme R. (1985), "Il futuro industriale di Venezia", in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Rapporto sulla rigenerazione industriale di Venezia, Paris.

Touring Club Italiano - Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1998), Turismo estero al Sud: una occasione di sviluppo, Roma

Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1996), Indagine campionaria sul turismo internazionale dell’Italia. Luglio. Agosto, Settembre 1995, Roma

Ufficio Italiano dei Cambi (1998), The Geography of International Tourism Demand in Italy, Roma

United Nations - World Tourism Organisation (1993), Recommendations on Tourism Statistics, Madrid - New York

World Tourism Organisation (1999), Seminar on Frontier Statistics in European Countries (Surveys on Inbound & Outbound Tourism), Madrid

18 For a formalization of the process see Prud'homme R. (1985), "Il futuro industriale di Venezia", in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Rapporto sulla rigenerazione industriale di Venezia, Paris.

23