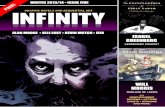

Infinity and Accident: Strategies of Enfoldment in Islamic Art and Computer Art

Transcript of Infinity and Accident: Strategies of Enfoldment in Islamic Art and Computer Art

An aniconic turn is stirring the contemporaryvisual and media arts. Less and less is present to perception;more and more is latent, in quiet surfaces that seem to be “hid-ing something in the image” [1]. The latent image waits to be“unfolded,” either subjectively, by the viewer, or by the forceof its interior logic. Figural images are increasingly being sub-ordinated to information, performativity, communication andother relatively nonvisual contents. This contemporary an-iconic tendency, which is a general movement in the arts of in-formation societies, occurs particularly with computer-basedart. One of the origins of this aniconic tendency in contem-porary art is the influence of Islamic art and thought on West-ern modernism.

Fascinating subject though it is, the Islamic genealogy ofWestern modernism is not my focus in the present essay. Itdoes, however, inform my claim here that the parallels betweentendencies in contemporary computer art and tendencies inclassical Islamic art are not happenstance but the manifesta-tion of historical connections. In turn, this Islamic genealogyof Western modernism should make it possible to examinecontemporary computer-based art in light of the impressivevariety of philosophical questions and aesthetic solutions foundin the varied works of Islamic art of past centuries. Without sug-gesting that Islamic art is a monolith, I want to apply histori-cal findings on Islamic art to questions about contemporaryvisual and media arts [2]. I intend to reveal a genealogical con-nection that has lain more or less latent since the wave of trans-mission of Islamic knowledge to Europe in the 12th century.

Invention, refinement and lively debate characterize the in-tellectual golden age of Islam, which may be dated from theestablishment of the Abbasid caliphate in what is now Iraq (forconvenience, I will continue to refer to the region as Iraq inthis paper) in 750 to the Mongol invasion in 1258. In the newcapital of Baghdad, the caliph Al Ma’mun (reign 813–833)founded the Beit al-hikmeh (House of Wisdom), a massive li-brary and center for translation and scholarship. Especially in the first two centuries of this period, philosophers and theologians intensely argued such issues as the nature of mat-ter, the relationship between cause and effect, and the com-prehensibility of the will of God. Their arguments, whileultimately subject to the political interests of the states theyserved, are literally set in stone in the great Islamic monumentsof their time and later eras—works that raise questions aboutimage and latency.

Contemporary aniconic art isbuilt not around the image, noreven the rejection of the image (itis not iconoclastic), but around animplicit set of information (for ex-ample, the database and the algo-rithm). The image is a selectiveunfolding of implicit information,and information is in turn a selec-tive unfolding of implicit experi-ence [3]. By the latter I mean thatall information is a selective actu-alization of historical events—statistics reflect a selectivearrangement of material experience; software reflects the la-

©2006 ISAST LEONARDO, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 37–42, 2006 37

T H E O R E T I C A L P E R S P E C T I V E

Infinity and Accident: Strategies of Enfoldment in Islamic Art and Computer Art

Laura U. Marks

Laura U. Marks (educator), School for the Contemporary Arts, Simon Fraser University,Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada. E-mail: <[email protected]>.

A B S T R A C T

Computer art and Islamic art, the two largest bodies ofaniconic art, share a surprisingnumber of formal properties,two of which are explored here.The common properties ofcomputer art and classicalIslamic art can be understood in light of moments in the historyof Islamic philosophy. In thesetwo cases, Islamic Neoplaton-ism and Mu’tazili atomism areshown to parallel, respectively,the logic of relations betweenone and infinity, and the basicpixel structure, that inform somehistorical monuments of Islamicart as well as some contempo-rary works of computer art. It issuggested that these parallelsare in part a result of Islamicinfluences on Western mod-ernism and thus that the geneal-ogy of computer art includesclassical Islamic art and thephilosophies that informed it.

Fig. 1. Mihrab, Mosque of Sultan Hassan, Cairo. (Photo © Alfred Molon)

bor of programmers; the evening newson television is a selective presentationof certain events; even poetry is the ac-tualization in words of a swath of mate-rial and psychic experience, the rest ofwhich remains virtual. It may be addedthat what is unfolded into information orimage can be considered actual, whilewhat remains enfolded remains virtual[4]. Enfoldment-unfoldment implies thatthe relation between two elements, suchas soul and matter, particle and wave, im-age and information, or information andexperience, is one not of dichotomy butof implicit relation [5].

In computer art, the image is the mereskin of an artwork whose underlyingstructure and raison d’être lie elsewhere: in its algorithm and database. Similarlyin Islamic aesthetics, generally speaking,the visual image is an expression of a di-vine “logic” that may or may not be madeperceptible. Both are characterized bytheir variety of strategies for unfoldingthe perceptible image from the imper-ceptible elements that drive it [6].

Several formal and structural proper-ties common to both classical Islamic artand computer art can be identified. Fun-damental to them all is:

1. A logic of enfoldment and unfold-ment. From it follow, though notalways obviously,

2. Aniconism: a tendency against priv-ileging the representational image.

3. Latency: a tendency for the work’sunderlying structure to remain in-visible or latent, perhaps to be man-ifested over time or to be teased outby the attention of observers.

4. Algorithmic structure: a structurebased on a series of instructionsthat manipulate information to pro-duce actions or images.

5. An emphasis on performativityrather than representation: thework of art plays out in time, un-folding image from informationand information from experience,

folds from information, such as the flori-ated Kufic writing of the Sh’ite Fatimidsof 12th-century Egypt [7]. On the otherhand, a belief that the relationship be-tween the worldly and the Divine can-not be understood rationally but can beapprehended mystically may give rise tofantastical figurative painting, as in thecourts of 16th-century Persia, with theirSufi-inflected Sunni orthodoxy [8].

In the intellectual hotbed of the Ab-basid caliphate in 8th- to 10th-centuryIraq, several radically different philoso-phies clashed and interwove, with impli-cations for the entire subsequent historyof Islam. These include, among others,the Greek-influenced Neoplatonism ofthe falasifa and the atomism sharply de-bated between the Mu’tazili rationalistsand the Ash’ari dogmatists (known assuch after the Mu’tazili reformer Abu’lHassan al-Ash’ari, d. 935) [9]. All thesetendencies variously struggled and throvein the intellectual climate of translation,synthesis and Islamization of receivedknowledge that was vigorously cultivatedby the Abbasid caliphs. These argumentshad direct implications for politics andwere inherited, institutionalized andtransformed by later thinkers and the po-litical powers behind them.

Islamic art does not exhibit a uni-fied discourse; its styles reflect historicalchanges, both gradual and abrupt, in pol-itics, theology and technology.Therefore,the examples I use cannot be taken as em-blematic of all Islamic art, nor of directcorrespondences between belief and ma-terial form. Some Islamic monumentsclearly index the theological and philo-sophical leanings to which their patronsor society adhered. For example, the Al-mohads of 12th-century North Africa,whose name derived from al-muwahhidun,“confessors of the unity of God,” viewedthe suggestion that God has attributes asblasphemous. This theological view wasreflected in their austere and (rare in Is-lamic history) iconoclastic art and archi-tecture. Almohad art tends to prune awayall attributes in order to approach the(unattainable) Divine Essence. Ibn Tu-mart (reign 1080–1130), the Almohads’ascetic and bellicose leader, adopted asevere version of Ash’ari theology, ledmilitary campaigns in Spain and NorthAfrica and cracked down on all forms of sensual pleasure. The Almohads de-stroyed the ornaments with which theirpredecessors had decorated their mosquesand whitewashed their polychrome dec-oration. The Great Mosque in Ibn Tu-mart’s birthplace of Tinmal, Morocco(1035), is a fortress-like structure whoseonly ornament, other than the mihrab

in the carrying out of algorithmsand/or the attentive recognition ofobservers.

6. An ease of translation among me-dia. Because the perceptible imageis animated by underlying informa-tion, the image may show up in a va-riety of media (e.g. in Islamic art:stone, wood or paper; in computerart: 2D images, sound or commandsto motors).

7. An emphasis, in seeming contrastto the logic of enfoldment and un-foldment, on the discreteness anddiscontinuity of information: Worksthat emphasize their own image orother manifest qualities may dis-avow awareness of the informationsource of these qualities.

Not all these properties can coexist.Nor are all the beliefs that underlie themcompatible.

MULTIPLICITYENFOLDED IN UNITYA basic premise of Islam, shared by all be-lievers, is Tawhid, or the absolute unity ofGod. The world’s multiplicity exists onlyas a function of the One. This basic doc-trine is stated in the Qur’an and was ini-tially developed by Islamic philosophersin a synthesis with Greek, Syriac andByzantine thought.

How can art indicate this relationshipbetween the unknowable Infinite and themultiplicity of the palpable world? I be-lieve it can be demonstrated that each of the various theological tendencies inIslam holds a different position on theform of mediation between the unifiedand unknowable God and God’s percep-tible creation; and that to each of thesepositions in turn corresponds a differentpractice of Islamic art, which is in turnhistorically variable. For example, a be-lief that one may rationally inquire intothe nature of God may be reflected in art-works that emphasize the way image un-

38 Marks, Infinity and Accident

Fig. 2. External mihrab,Mosque of Sultan Hassan,Cairo. (Photo © SamirahAlkassim)

(the prayer niche on the qibla wall, thewall facing Mecca) consists in the pointedarches in the outer courtyard and multi-lobed arches in front of the qibla wall.The absence of visual or tactile diversionseases the visitor into a contemplativestate.

I note that similar radical aniconismcharacterizes some works of computer art that abjure the graphical interface infavor of a visually ultra-minimal indexpage. One example is a program pro-duced by the artist-hacker organization0100101110101101.org, known for intro-ducing a benign computer virus as a workof art at the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001.Their recent project, life_sharing, makesthe artists’ entire hard drive, from textsto private e-mail, open to any on-line vis-itor. Using a free Linux-based operatingsystem and a list of directories, but with-out a single image interface, the visitorenters the guts of 0100’s computer. Thisproject attempts to strip away all inter-faces in order to confront the user withthe infinitely extensive plane of digitalmemory.

Other examples of Islamic art can begiven in which ideology and aestheticsare closely aligned. Yet in most Islamicworks of art, historical styles commingle,serving local political purposes yet notnecessarily evincing a single unalloyedtheological view. Neoplatonism and atom-ism, though in principle opposed, his-torically coexisted. Similarly, Islamic artoften evinces qualities corresponding si-multaneously to both of these, and in-deed other, philosophies, as do the twolate and well-known monuments of clas-sical Islamic architecture that furnish mycentral examples. The effect is admittedlysomewhat ahistorical. The first is themihrab of the Sultan Hassan Mosque,from 14th-century Mamluk Cairo; thesecond, the dome of the Hall of the TwoSisters from the Alhambra in Granada of14th-century Nasrid Andalusia.

ISLAMIC NEOPLATONISM: ∞ IS ENFOLDED IN 1Absolute unity is also a Neoplatonist doc-trine, associated especially with Plotinus,who argued that the One generates theuniverse through emanation of the lightof reason. Abu Yusuf Ya’qub al-Kindi (d.866), Islam’s first systematic philosopher,adapted Plotinian thought to monothe-ism by replacing the principle of emana-tion with divine creation ex nihilo, inwhich God is outside time but creation isfinite [10]. Abu Nasr al-Farabi (d. 950),by contrast, developed an emanationisttheory of the structure of being, whereby

of prayer in that direction. Mats spreadfor prayers at home act as needles drawntoward the magnetic presence of God.Prayer in Islam, in short, performs thepresence of the One Infinite God as thebeckoning absence that directs prayer inphysical, temporal, directional space.

The mihrab of the much-admired Sul-tan Hassan mosque in Cairo, completedin 1356, spectacularly enacts the rela-tionship between that unknowable, infi-nite One and the multiplicity that strivestoward it (Figs 1–3). At the base of thespandrel supporting the dome of theniche, a very modest “Allah” is inscribedin black letters. From this vanishing pointradiate rays of colored marble, black,white, green, red and yellow. As their dis-tance from the word “God” increases,these marble stripes metamorphose frac-tally, the border of each tangling with the adjacent one. It is a virtuosic render-ing of a typical application of Mamlukmarble encrustation. At the edge of themihrab the rays resolve into an exceed-ingly ornate pattern of oblongs androundels of precious marble and in-scriptions in gold. As from the decep-tively simple word for God at the centerspring ever-more elaborate forms, theSultan Hassan mihrab performs the rela-tionship between 1 and infinity. The infi-nite multiplicity of the world unfoldsfrom the infinite unity of God, and, as a viewer’s eye travels back to the navel of the niche, unity re-enfolds multiplic-ity. The pleasure, both spiritual and aes-thetic, of contemplating it lies in themarvelous inventiveness by which multi-plicity is shown to spring from unity.

It must be said that patronage as muchas theological inspiration informs thedazzling effects of the decoration of theSultan Hassan mosque. In Mamluk Cairo,as Yasser Tabbaa writes, skilled stone-masons (often from Syria) competedwith one another to achieve ever-more-dazzling effects with polychrome inlay,and the effect would have been to glorify

God, the First Being, by thinking aboutHimself, gives rise to a Second Being andFirst Intellect, which in turn generates a third, until a tenth, Active Intellect me-diates between the celestial and earthlyrealms [11]. A logic whereby the multi-plicity of creation unfolds from the infi-nite unity of God also characterizes thethought of the Ikhwan al-Safa (Brethrenof Purity), a Neopythagorean secret so-ciety in 10th-century Basra that authoreda popular pamphlet. In the mathemati-cal universe of the Brethren of Purity,God is the First Principle of all things just as 1 is the first principle of all num-bers. Thus the relationship God:Universeequals the relationship of 1 (indivisibleunity) to other numbers (multiplicity).

Most Muslim thinkers did not advocatetrying to come face to face with the Di-vine. Rather they held that beauty is en-gendered in the sophisticated, dialecticalrelationship between unity and multi-plicity. The Baghdadi literary theoristAbu Bakr ‘Abd al-Qahir al-Jurjani (d.1078) wrote that in all arts and crafts, “themore widely differed the shape and ap-pearance of their parts are and then themore perfect the harmony achieved be-tween these parts is,” the more “fascinat-ing” and praiseworthy the resulting workwill be [12]. The best art invites a medi-tation upon the subtle relationships be-tween unity and multiplicity. For art, asfor philosophy, by this criterion there is no compulsion to collapse the infin-ity of forms to 1 but rather a desire todemonstrate the sophisticated relation-ship between them. The influence ofNeoplatonism on some Islamic monu-ments has been noted by Gülrü Neci-poglu in her authoritative work TheTopkapi Scroll and also by Asli Gocer [13].

In Islam, God is not represented by anicon but indicated through a trajectory.The holiest place in a mosque is themihrab. It functions both like a compass,indicating the direction of divine pres-ence, and like a lens, focusing the energy

Marks, Infinity and Accident 39

Fig. 3. Close-up, externalmihrab, Mosque of SultanHassan, Cairo. (Photo © Samirah Alkassim)

the sultan, as well as the Divine, in theeyes of worshippers [14]. Moreover, bythis time Egypt was under the sway ofSunni religious beliefs, which includedthe outright denunciation of the princi-ple of emanation as polytheistic (as, if allBeing is an emanation of God, this im-plies that God is somehow plural) [15].Nevertheless, given the popularization ofNeoplatonist thinking and its inextrica-ble admixture with more orthodox the-ology, the Sultan Hassan mosque bothmystifies and reflects the relationship ofthe Divine with the world.

Good computer art, by the Neopla-tonist criterion I am proposing here,similarly exploits the complexity ofunfolding-enfolding relations. It does notimmediately collapse the perceptible im-age to its numeric basis in database andalgorithm. Nor, of course, does it remainstatically at the level of image. Rather itinvites the perceiver to marvel at the rich-ness with which the perceptible imageunfolds from the numeric base. John Si-mon’s web work Unfolding Object [16](Color Plate H) initially presents a faceas impassive as Malevich’s black square orthe name of God in the Sultan Hassanmihrab. Its initial page shows a coloredsquare on a colored background. Theuser clicks the square to “unfold” succes-sive “pages,” which are simply animatedto appear to open in three dimensions.Darker color and creases (suggested bylines across the page) indicate that pre-vious visitors have unfolded these pages.Those never altered unfold into a brightnew page. The process creates an in-creasingly complex, impossibly dimen-sional object, looking sometimes like a mauled chrysanthemum, sometimes like the kinky-pipes screensaver of vin-tage PCs.

Interestingly, the infinite iterations ofthe book that are enfolded in UnfoldingObject’s software must be unfolded so-cially, by the people who engage with thework on-line. Simon writes, “To realizethis object in software was a great joy forme because all the potential for the ob-ject is contained in a very few lines of writ-ing. When the code is activated—thereare more ways to unfold it than we havetime in our lives to explore” [17]. It is notnecessary for users to be on-line at thesame time: The Object encodes actions car-ried out upon it in a rudimentary formof communal memory. Unfolding Object’spotential is contained in its source codeand unfolded by the user. The longer oneengages with it, the more complexity, log-ical depth and social extension the sim-ple shape reveals. The work’s title refersto quantum physicist David Bohm’s the-

cabulary of virtuality surrounding newmedia. This approach was derived fromthe Qur’an’s distinction between the perceptible (shahada) and the unseen(ghayb), which includes not only divinebeing but also all that is in the past or thefuture [19]. The Mu’tazili of Basra main-tained that nonexistent objects (ma’dum)are “things” and thus objects of knowl-edge. For those things that do exist, theMu’tazili developed a complex realism in which all things that have acquiredexistence (unlike God, who has always ex-isted) can be categorized as either atomsor “accidents”: indivisible particles ofmatter, or the qualities, such as color andmovement, that accrue to them. Accord-ing to the Basrian Mu’tazili, atoms occupyspace, form larger units additively, meas-ure space by occupying it, and preventother atoms from occupying the samespace [20].

The Mu’tazili passionately debated re-lationships between atom and accident.In a radical version of Mu’tazili atomism,absolute occasionalism, Ibrahim al-Naz-zam (d. 845) of the Basrian school ar-gued that both motions and bodies lastonly a moment and are continually re-created (or not) by God. Things exist be-cause God commands, Kun! (“Continueto exist!”) [21]. The opposite of contin-ued existence is fana’, ceasing to exist.Only by God’s grace do we continue toexist at every moment.

In some cases, and ultimately, the ra-tionalism of the Mu’tazili atomists gaveway to mysticism, a reluctance to ascribecausality to the unknowable ways of God.Al-Ash’ari insisted that it was dualistic toinquire how God’s attributes inhered inGod, and polytheist to claim that humanshad free will, that is, were the authors of their own actions. While the rationaltradition struggled against rising conser-vative religious pressure [22], Ash’ariMu’tazili thought gained power. It wasmodified by conservative anti-rationalistthinkers, chiefly al-Ghazali (d. 1111).Humility and awe in the face of the om-nipotent were called for.

Yasser Tabbaa correlates the develop-ment of a uniquely Islamic architecturalform with Mu’tazili atomistic theory, es-pecially the moderate occasionalism ofIbn al-Baqillani (d. 1013) [23]. This form is the muqarnas dome, which seemsto have first appeared on mausoleums in Iraq and Upper Egypt in the 11thcentury. Built from thousands of tiny,repeated cells called muqarnas, it em-phasizes not underlying unity but infini-tesimal parts—like the atoms of theMu’tazili. In most of its iterations, themuqarnas dome disavows the rational re-

ory of the implicate order, or an imper-ceptible latent order by which apparentlydisparate perceptible events are con-nected [18]. The similarity to Neopla-tonist Islamic thought is evident.

What I find most interesting about thecomparison between the Sultan Hassanmihrab and Unfolding Object, however, isthat infinity is already there in the object,waiting to be discovered by users. The twoworks of art evoke the difference betweena fathomable infinity—that encoded inSimon’s software—and an unfathomableinfinity, that of the Deity to whose un-knowable presence the mihrab points. Itis here that the parallels between a sacredand a secular work diverge. A work suchas Unfolding Object invites a wonder beforethe infinite that ultimately converges onthe material (the experience of the pro-grammer) or the conceptual (the cre-ative speculation to which the work givesrise), but not the divine.

MU’TAZILI ATOMISM: INDEPENDENCE OF PIXELSThe Neoplatonist understanding ofTawhid or divine unity emphasizes the in-terconnectedness of the universe as amanifestation of the One God. Anothercurrent in the intellectual debates of Ab-basid Iraq places less emphasis on God’sinconceivable unity and more on God’sinconceivable power. This is the thoughtof the Mu’tazili atomists. While the Neo-platonist universe is highly structured,the atomist universe is held together by the will of God alone. It is striking that, while the falasifa emphasized thatmatter is an emanation from God, thecontemporaneous atomist movementemphasized the complexity and ultimateunknowability of the relationship be-tween God and matter.

The Mu’tazili were Islamic theologianswho, like the falasifa, were devoted to vig-orous rational debate, but they relied lessupon Greek philosophy than did thefalasifa and more upon Qur’anic sources.For a brief period in the 9th century,their argument that humans could use ra-tionality to understand God’s justice wasofficial doctrine in the Abbasid caliphate;it then fell precipitously from favor.

In their attempt to explain God’s rea-soning, the Mu’tazili developed a so-phisticated ontology that would permitunderstandings of the causal relations be-tween invisible and visible, divine andearthly. Using logic rather than mysti-cism, they cultivated a notion of virtual-ity that makes it possible to contemplatethings that do not exist—which seemsstrikingly similar to the contemporary vo-

40 Marks, Infinity and Accident

lationship between parts and concealsthe structure of the dome, making it lookinsubstantial. A famous example is themuqarnas dome in the Hall of the TwoSisters at the Alhambra, that late flowerof Umayyad princely architecture (Fig.4). Subdivided into thousands of stalac-tite-like forms, admitting myriad pointsof sunlight, the dome is a dizzying danceof light and shade. If the concentric dec-oration of the Sultan Hassan mihrabinvites contemplation of the relation-ship between God and the created uni-verse, the muqarnas dome argues that wecannot know what that relationship is.(Again, historical conscience requires meto caution that the Alhambra is by nomeans a “typical” atomist monument.)

A hypothetical Mu’tazili atomist cin-ema is described by Jalal Toufic, who sug-gests that film’s frame-by-frame structuresupports an aesthetic of appearance-dis-appearance [24]. What really “sutures”the viewer into a film, Toufic provoca-tively suggests, is not the image but thejump cut, which “alerts him or her to hisor her substitution by another, similar en-tity, and his or her annihilation into theone and only Subject.” Subsumption intoa larger entity and incomprehension ofone’s relation to that powerful other ex-cept through submission: these describeboth the Ash’arite philosophy and a cer-tain relationship to mechanical image-making media.

Atomism emphasizes the level of in-formation while not presuming to knowhow it is related to (unfolded from) thelevel of experience. It demands faith. Incomputer-based art, the expression ofimage by information is even more arbi-trary than in cinema. The universe ofcomputers is composed of units of infor-mation. There is no necessary relation-ship between the “friendly” interface, askin of myriad pixels, and the underly-ing software and hardware. Thus manyusers approach computers with an atti-tude not of understanding (of how thevisible part relates to the concealed cal-culations) but of wonder, mystificationand sometimes fear.

A state of awe or blissful annihilationis courted by some artworks that crashcomputers. Others wrest control of theinterface away from the user or collapseit into an enfolded state. The standard-bearer of fana’ in the digital age is Jodi.org, whose complex programming ren-ders opaque the (supposed) transpar-ency of standard graphical user interfaces[25]. Privileging the independence ofpixels juddering on the desktop, pro-grammers Joan Heemskerk and DirkPaesmans insist on the non-necessity of a

because Western intellectual historianshave disavowed Arab/Muslim links ordismissed their importance. Historians of mathematics and science, includ-ing George Saliba and Roshdi Rashed,demonstrate that Arabic scholars cri-tiqued and significantly developed Greekworks, producing a specifically Arabicbody of thought, and that these workswere known, translated and taken up byEuropean scholars. Even after the Cru-sades and the expulsion of Muslims andJews from Spain in 1492 (many stayed onand concealed their faith), Arab and Is-lamic scholars and artists were invited towork in European courts. Italian scholarstraveled to the Islamic world to study Ara-bic during the Renaissance [27]. Themassive work of translation of Arabictexts into Latin continued throughoutthe Middle Ages and as late as the 17thcentury. The Latin word algebra enfoldsthe Arabic al-jabr (restoration), from the title of Mohammad Ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi’s (d. 850) treatise on practi-cal arithmetic, Kitab al-jabr w’al-muqabala,which was translated by Robert of Kettonin the multicultural scholarly center ofToledo in the 1140s [28]. Thus did Al-Khwarizmi, mathematician and chief li-brarian of the Beit al-hikmeh, give hisname to the Latin word algorithm.

In the arts, as in philosophy, mathe-matics and science, Islamic plastic ex-pression deeply informed Europeanartistic innovation from the Renaissanceto modernism. Many of these connec-tions have also been disavowed. How-ever, especially with the rise of abstract,

correlation between perceptible formsand the software that gives rise to them.

For the Islamic atomist philosophers,the ontological separation between Godand the palpable world could either oc-casion a sophisticated inquiry into thepossible relationship between them or dis-courage rational explanation. Historicallyin Islamic philosophy there was a shiftfrom the first approach to the second.For Jodi (and similar works, such as thecontroversial m9ndfuck.com, EmmanuelLamotte’s interface art at erational.com,and Antoni Abad’s 1.000.000), what firstengenders wonder, awe or the sublimeexperience of believing that one’s fileshave been destroyed gives way to a criti-cal understanding of the relationship be-tween software and its effects. Stressingthe lack of necessary relation betweenthe interface and the underlying infor-mation, “atomist” computer artworks cri-tique the mystification of the “friendly”interface deployed by conventional com-puter media.

HISTORICAL ENFOLDMENTSHistory too exists in relations of enfold-ment. What people know of the past at a given moment is the merest surface ofenfolded events, which they have man-aged to unfold [26]. Islamic knowledgeis inextricably enfolded in Europeanphilosophy, science, technology and cul-ture. These connections are only knownselectively, and most will never be known.Some of these connections are onlyrecently coming to light in the West,

Marks, Infinity and Accident 41

Fig. 4. Muqarnas dome, Hall of the Two Sisters, Alhambra. (Photo © Hazem Ismail Sayed.Courtesy of Aga Khan Visual Archives, Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

haptic and subjectivist practices in Euro-pean art from the late 19th century, Is-lamic art had an undeniable impact onWestern artists. Undoubtedly the manytechniques of abstraction, algorithmicconstruction, tactile surface qualities,meditative repetition and other qualitiesfound in various Islamic arts influencedthe rise of Western modernism [29].

Why should scholars and artists nowtry to unfold another aspect of the his-tory of Islam? We are at a point where theIslamic heritage latent in Western mod-ernism can inform contemporary effortsto make information culture meaningfuland responsive. In this secular and multi-confessional age, the ultimate source ofexperience differs from the divine sourceto which Islamic art refers. In addition,the information unfolded in our con-temporary images tends to encode power(state information, corporate informa-tion, financial information) in a way thatrequires combative discernment morethan calm contemplation. The richness,however, with which Islamic art, in all itshistorical variants, invites a contempla-tion of the relationships between the per-ceptible and the imperceptible can pushus to make and want images whose seem-ing aniconism conceals an enfolded ex-perience that is worth seeking out.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Center for Behavioral Research at theAmerican University of Beirut for sponsoring me asa visiting scholar in 2002–2003, which gave me theinitial opportunity to develop this research. David Si-monowitz of the G.E. von Grunebaum Center forNear Eastern Studies at University of California atLos Angeles made invaluable suggestions to the man-uscript, for which I am most grateful. I also thank myanonymous reviewers for Leonardo for their consid-ered and rigorous questioning, and the editors ofLeonardo for their graceful supervision of the publi-cation process.

References and Notes

1. Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image, HughTomlinson and Robert Galeta, trans. (Minneapolis,MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1989) p. 45.

2. This essay concentrates on contemporary works ofart made with and reflecting on computer software.However, many of the principles I propose here ex-tend to other relatively aniconic arts, as well as toworks made without computers that are nonethelessinformed by the culture of information.

3. The triadic philosophy of Charles Sanders Peirceinforms this model of implication-explication or en-folding-unfolding between three levels, Experience(or Reality), Information and Image, which I devel-oped in an attempt to analyze the status of images in

18. See David Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Or-der (New York: Routledge, 2002).

19. Tilman Nagel, The History of Islamic Theology: FromMuhammad to the Present, Thomas Thornton, trans.(Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press: MarkusWiener Publishers, 2000) pp. 115–116.

20. Alnoor Dhahani, The Physical Theory of Kalam:Atoms, Space, and Void in Basrian Mu’Tazili Cosmology(Leiden, the Netherlands; New York; and Cologne,Germany: E.J. Brill, 1994) p. 61; Yasser Tabbaa, “TheMuqarnas Dome: Its Origin and Meaning,” Muqar-nas 3 (1985) pp. 68–69.

21. Dhahani [20] p. 45.

22. The famous “closing of the doors of ijtihad,” orpronunciation that the Qur’an needed no further in-terpretation—at least among Sunni Muslims—wasmore or less achieved by the beginning of the 13thcentury.

23. Tabbaa [14] p. 69. Tabbaa argues that thearabesque, overall star patterns and the increasingsubdivision of music similarly reflect the dominantphilosophy of Ash’ari atomism.

24. Jalal Toufic, “Middle Eastern Films before theGaze Returns to Thee—in Less than 1/24 of a Sec-ond,” in Jalal Toufic, Forthcoming (Berkeley, CA: Ate-los, 1999) pp. 115–136.

25. Readers unfamiliar with Jodi may visit <www.jodi.org>. See Tilman Baumgartel, “Interview withJodi,” Rhizome (19 May 2001) <http://rhizome.org/thread.rhiz?thread=1770&text=2550#2550>.

26. This is a version of Michel Foucault’s archaeol-ogy of knowledge that understands discontinuitiesbetween discursive entities in history as deep foldsrather than ruptures. See Michel Foucault, The Ar-chaeology of Knowledge, A.M. Sheridan Smith, trans.(New York: Pantheon, 1972).

27. See, for example, Roshdi Rashed, The Developmentof Arabic Mathematics: Between Arithmetic and Algebra(Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer, 1994); GeorgeSaliba, “Rethinking the Roots of Modern Science:Arabic Scientific Manuscripts in European Li-braries,” Occasional paper (Washington, D.C.: Cen-ter for Contemporary Arabic Studies, GeorgetownUniversity, 1999).

28. María Rosa Menocal, The Ornament of the World:How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture ofTolerance in Medieval Spain (Boston: Little, Brown andCompany, 2002) pp. 179–180.

29. See, for example, Philippe Büttner, “In the Be-ginning Was the Ornament—From the Arabesqueto Modernism’s Abstract Line” (pp. 86–105) andother debates on the influence of Arabic calligraphyand the “arabesque” on European painting inMarkus Brüderlin, ed., Ornament and Abstraction: TheDialogue between Non-Western, Modern, and Contempo-rary Art (Basel: Fondation Beyeler, 2001). I explorethe relationship between the theories of perceptionof Ibn Al-Haytham (and others) and the transmis-sion of Islamic aesthetics to Europe in another pa-per, “Islamic Aesthetics, Modern Attention, and theAbstract Line,” two versions of which are forthcom-ing in the proceedings of “Sense and Sensations: Onthe Performativity of Perception” (Frei UniversitätBerlin, November 2004), and in Christina Lammer,Cathrin Pichler and Kim Sawchuk, eds., Verkörpe-rungern (Patient Embodiment).

Manuscript received 2 September 2004.

the information age. For a more detailed discussion,please see my essay “Invisible Media,” in Anna Everettand John T. Caldwell, eds., New Media: Theories andPractices of Digitextuality (London and New York: Rout-ledge, 2003). On triadic thought, see Charles SandersPeirce, “The Architecture of Theories” and “The Lawof Mind,” in Justus Buchler, ed., Philosophical Writingsof Peirce (New York: Dover, 1955) pp. 315–323,339–353.

4. Deleuze succinctly describes the relationship be-tween actual and virtual, as informed by the thoughtof Leibniz and Bergson, in Gilles Deleuze and ClaireParnet, “L’actuel et le virtuel,” in Gilles Deleuze andClaire Parnet, Dialogues (Paris: Flammarion, 1996)pp. 179–184. Deleuze’s model of what can be actual-ized in a given historical moment is informed by Fou-cault’s archaeology of knowledge; see Gilles Deleuze,Foucault, Séan Hand, trans. (Minneapolis, MN: Uni-versity of Minnesota Press, 1988).

5. I derive the term enfoldment from a reading ofDavid Bohm and Basil J. Hiley, The Undivided Uni-verse: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory(London and New York: Routledge, 1993) and GillesDeleuze, Le Pli: Leibniz et le Baroque (Paris: Minuit,1988).

6. Another scholar who is pursuing the parallel be-tween Islamic art and computer art is Simon Yuill;see his essay “Ibn al-Bawwab and the Bastard Codes”(2003) at <www.lipparosa.org>. Yuill points out thatIslamic art is a precedent for computer art in its useof notational or programmatic media, specifically inthe case of calligraphy. His observations corroboratethe shared qualities in Islamic and computer art ofalgorithmic structure and intermedial translation.

7. Gülrü Necipoglu points out that the persistenceof floriated Kufic, from whose letters spring leaves,vines, and even animals, was one of the signs of Fa-timid resistance to the Sunni revival until the 12thcentury. Gülrü Necipoglu, The Topkapi Scroll: Geome-try and Ornament in Islamic Architecture (Santa Mon-ica, CA: Getty Center for the History of Art andArchitecture in the Humanities, 1995) p. 103.

8. See Sheila R. Canby, The Rebellious Reformer: TheDrawings and Paintings of Riza-yi Abbasi of Isfahan (Lon-don: Azimuth, 1996), and Anthony Welch, “Worldlyand Otherworldly Love in Safavi Painting,” in RobertHillenbrand, ed., Persian Painting from the Mongols tothe Qajars (London: I.B. Tauris, 2000) pp. 301–317.

9. The term falasifa is borrowed from the Greek. Theterm mu’taliza, or Islamic rational philosopher, des-ignates those who withdrew (I’tizal) from factionsformed during the first Muslim civil war.

10. Majid Fakhry, Islamic Philosophy, Theology, and Mys-ticism (Oxford, U.K.: Oneworld, 1997) p. 25.

11. Oliver Leaman, An Introduction to Classical IslamicPhilosophy, 2nd Ed. (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford Univ.Press, 2002) p. 18.

12. Necipoglu [7] p. 189.

13. Necipoglu [7] pp. 185–189; Asli Gocer, “A Hy-pothesis Concerning the Character of Islamic Art,”Journal of the History of Ideas 60, No. 4 (1999) pp.683–692.

14. Yasser Tabbaa, “The Muqarnas Dome: Its Originand Meaning,” Muqarnas 3 (1985) pp. 68–69.

15. Necipoglu [7] p. 192.

16. See <unfoldingobject.guggenheim.org>.

17. John Simon, e-mail communication to the au-thor, 8 January 2003.

42 Marks, Infinity and Accident

ANNOUNCING

ISEA2006 Symposium

5–13 August 2006, San Jose, California

The ISEA2006 Symposium is being held in conjunction with the first biennial ZeroOne San Jose GlobalFestival for Art on the Edge in San Jose, California, 5–13 August 2006. The themes for the symposium andfestival are: Interactive City, Community Domain, Pacific Rim and Transvergence.

The symposium and festival will be located primarily in numerous venues in San Jose’s downtown core,including the San Jose McEnery Convention Center, the Martin Luther King Jr. Library, the Tech Museumof Innovation and the San Jose Museum of Art, which will convert its café into an interactive café withextended hours during the festival. The main exhibition will include the work of over 100 artists.

San Jose State University will host a pre-conference Pacific Rim New Media Summit and provide low-costartist housing during the festival. Plaza de Cesar E. Chavez will be a central site for open-air installationsand performances, including a “container culture” exhibition and a nomadic architecture camp. In addi-tion, there will be projects throughout the city of San Jose as part of the conference’s Interactive City andCommunity Domain themes.

See <http://isea2006.sjsu.edu/index.html> for more details.

The Pacific Rim New Media SummitA Pre-Symposium to ISEA2006

7–8 August 2006, San Jose, California

The political and economic space of the Pacific Rim represents a dynamic context for innovation and cre-ativity. Experimentation in art, science, architecture, engineering, design, literature, theater and music isresulting in the emergence of new forms of cultural production and experience unique to the region. Thecomplex relations and diversity of Pacific Rim nations are exemplified throughout the hybridized commu-nities that compose Silicon Valley.

As part of the ISEA2006 Symposium, the CADRE Laboratory for New Media at San Jose State Universitywill host a 2-day pre-symposium entitled the Pacific Rim New Media Summit, co-sponsored by Leonardo.With a purview encompassing all states and nations that border the Pacific Ocean, the summit is intendedto explore and build interpretive bridges between institutional, corporate, social and cultural enterprises,with an emphasis on the emergence of new media arts programs in seven areas: Creative Community,Curatorial, Education, Directory, Eco-Social Activism, Mobile Computing and Urbanity, and Latin Ameri-can—Pacific/Asia New Media. This trans-disciplinary event will have a specific focus on educationalmethodologies and practices.

For more information, visit <http://isea2006.sjsu.edu/prnms.html>.