Independent Review into the Future Security of the ...€¦ · Web viewTraffic and transport: The...

Transcript of Independent Review into the Future Security of the ...€¦ · Web viewTraffic and transport: The...

THE CASE TO REDUCE THE REGULATORY BURDEN ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF UTILITY-SCALE SOLAR PROJECTS

A Submission to the Independent Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity

Market

Dr. Turlough F. Guerin GAICD

Sunbury, Victoria

Email: [email protected]

Terms of Reference

The following consultation questions appeared in the original discussion briefing and on

page 24 of the Independent Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity

Market - Preliminary Report (December 2016).

The world is acting to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Australia has a target to reduce

emissions by 26 to 28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. The electricity sector has an

important role to play in achieving Australia’s emissions reduction targets. Not only is it

Australia’s largest source of emissions, but also a large source of opportunity for abatement

and innovation. This will require stable and effective emissions reduction policies to support

the necessary investment in long-lived generation and network assets while maintaining

security and reliability.

3.3 What are the barriers to investment in the electricity sector?

3.4 What are the key elements of an emissions reduction policy to support investor confidence and a transition to a low emissions system?

This submission provides a perspective on this section of the original discussion paper and

is a response to consultation Questions 3.3 & 3.4 only.

Page 1 of 22

Highlights

The renewable energy sector in Australia is highly regulated and NSW in particular,

reflected in the extensive approval and consent conditions and their cost impacts.

This submissions highlights observations from a case study into the regulation of a

utility-scale solar energy (USSE) PV construction project in Central NSW.

The Environmental Impact Statement and Assessment (EIS) process verified some

of the expected project risks, however, the overall approvals process and the

impacts of compliance were material to adding unnecessary burdens to the project,

and therefore acting as a barrier to further future investment.

The actual risks observed during construction and post-construction (into operations

and maintenance), were effectively managed through a mix of black letter law, co-

regulation and self-regulatory mechanisms.

We need to reduce the regulatory burden in constructing new clean generation.

A reduced regulatory burden, balanced by more self- and co-regulation, will help

incentivise further investment into the renewable energy sector in Australia.

Executive Summary

A review of legislation in Australia’s most populous and most regulated construction

environment was undertaken in the jurisdiction of New South Wales (NSW). Logistics,

fauna, biodiversity, noise, general administration, infrastructure and camp establishment

issues, and the construction and operational environmental management plans, have the

most planning approval requirements. A case study on the construction of a USSE PV plant

is described highlighting how a range of identified (expected) environmental and community

risks (totalling 296) were not experienced in the field during construction, and those risks

that did eventuate were managed effectively. It is argued that a paradigm shift is needed in

the current statutory planning processes such that new renewable energy generation is

considered in a fundamentally different way to which new non-renewable generation is

evaluated. This should include a holistic view of the role of the community in the design,

and gaining access to, such new renewable energy generation so there is comprehensive

buy-in from these critical stakeholders. There is a need to reduce regulatory red tape to

encourage investment to help reach the state’s (and ultimately the country’s) target for

renewable energy installations, while at the same time protecting communities, the

environment, human health and safety. This submission argues and provides support for a

reduction in the environmental and community related regulatory burden for new renewable

energy projects, presenting evidence for low actual impacts compared to those identified as

expected during the planning and approval stages. This will help improve Australia’s

attractiveness as a target for investment in renewable energy.

Page 2 of 22

INTRODUCTION

Large-scale Solar PV (defined as greater than 5 MW) remains in its infancy in Australia. At

the end of 2015, Australia had 19 operational solar projects larger than 1 MW in size,

including 17 solar farms which use solar photovoltaic (SPV) technology and two solar

thermal plants – a total of 217 MW of potential generating power. When the projects

currently under construction are complete, installed capacity of large-scale PV will total 262

MW [1]. However, 2017 is expected to represent a “transformational” year for large scale

solar development in Australia, with over 20 projects likely to reach financial close. While

the 12 ARENA supported projects are likely to be the first to lock in funding, an additional

pipeline of projects is set to attract overseas and domestic investors. This is still well behind

the installed capacity of comparable international markets. The cost trajectory of USSE

Solar PV is expected to see the technology become competitive without additional support

within the medium term.

The Regulatory Landscape

For large scale developments in New South Wales (Australia), the range of legal

requirements are identified in the EIS/EIA stage of the developments. The applicable laws

range from those addressing climate, planning, to operational environmental issues [2].

There is a tension between the needs for the development of any new sector, balanced

with that of black letter law and industry self-regulation. Self-regulation has been shown to

be ineffective in some sectors, becoming a “tick and flick” exercise, and particularly when it

comes to safety and environmental performance [3, 4]. However, self-regulation is an

important part of the toolkit to regulate industry [5], particularly in the clean energy sector as

it struggles to establish itself in Australia.

Improving environmental performance requires regulatory mechanisms that stimulate

industry’s development, and transfer and adoption of technologies that protect and

enhance the environment [6]. Traditional, direct environmental regulation will always be

required to motivate laggards who are the slowest to adopt the most appropriate course of

action. Proactive companies (innovators and leaders) on the other hand in any industry,

will respond to the opportunities and incentives that self-regulation offers to improve

environmental and community performance.

An excessive reliance on black letter law to regulate the renewable energy sector in

Australia may only serve to further stifle innovation and ultimately growth, and at the same

time, discounting the long term environmental and social benefits such technological

advancements (in clean energy) can bring.

Page 3 of 22

An Overview of Solar PV Developments

A solar PV facility typically comprises a series of PV panel arrays and inverters, mounts,

trackers (if used), cabling, monitoring equipment, substation and access tracks. The

amount of electricity generated by a PV facility will be dependent on a number of factors

including the type, location of the installation, positioning of the panels, and whether

trackers are used. In essence, USSE developments conform to construction methodologies

common to earthworks, civil and structural, trenching, and electrical work scopes.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this submission is to demonstrate how the current statutory laws were

complied to through the application of a case study. These laws relate to approval (consent

conditions), access to land suitable for solar PV installations, impacts on the community,

and operationally-focused laws governing direct environmental impacts from the project.

A case study is described and presents the environmental legal background to the project

and illustrates the relatively low negative impact a USSE project had on the local

environment and community.

The submission intends to provide support to the concept that care should be taken by

planning regulatory authorities in Australia not to over-regulate the development and

construction of new renewable energy generation to the point where investment becomes

unattractive.

METHODS

Case Study Site Location, Description and Construction Process

The site is located in Central NSW, Australia, approximately 10 km west of the nearest

township. The USSE power plant (now completed and in operations and maintenance

stage), has an installed capacity in excess of 100 MW, the largest plant of its kind in

Australia at the time of this submission (March 2017). The project was constructed

on entirely rural land and was located on one land parcel. Approximately 250 ha

of land was required for the plant. Along with the solar plant, the development included the

installation and operation of a 132 kV transmission line, approximately 4 km long x 40 m

(wide) to the main network interconnection. The solar plant consists of more than one

million photovoltaic (PV) modules. The modules were mounted on steel post and rail (table)

support structures up to 2 m in total height. Supporting infrastructure includes the

installation of above and underground electrical conduits, construction of a substation, site

Page 4 of 22

office and maintenance building, provision of perimeter fencing, unsealed access road and

the transmission line.

Regulatory Review

A review of the relevant laws and a comprehensive planning application and EIS (EIA)

review process was conducted prior to the construction stage. The proposed solar plant

described in the case study was declared to be a State Significant Development for the

purposes of the NSW Environmental Planning and Assessment (EP&A) Act (1979). The

commonwealth and state legislation used to develop the approval documentation, and

which formed the basis of the controls used in the construction, are discussed in the results

and discussion section. Specific legislative requirements manifested in a series of consent

conditions for the project. The project was also constructed under the following self-

regulatory mechanisms including an ISO 14001 based environmental management system,

International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) for community consultation and to

an extent, AS4801 for safety management, though their relative contribution was minimal

compared to the black letter law of the consent conditions (and other legislation in addition

to the consent conditions).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Environmental and Community Impacts from Case Study

During the construction stage of the case study project, various environmental and

community management plans were developed as part of the approval conditions and

implemented. Table 1 presents all of the impact areas that were measured during the

construction stage.

A high-level summary of the groupings of consent conditions for the case study project

development have been prepared from the 296 individual consent conditions in the

approval documentation, along with their expected and actual impacts during the

construction process (Table 2). These groupings included logistics impacts, fauna,

biodiversity and flora management, visual impact, fire, soil, water and dust management

and waste management and resource use impacts, and were all identified in the EIS.

A summary of the targets and actual environmental and community outcomes during

construction of the case study project is given in Table 3. A key finding is that the observed

risks did not correlate with the expected environmental and community risks that were

ascertained when the consent conditions were developed. These results are discussed in

further detail in another publication [7].

Page 5 of 22

A Greater Role for Self-Regulation?

Self-regulation, including codes of practice and standards, are developed by industry for

many diverse reasons, including as a means of showing social responsibility, and a desire

by industry to reclaim the agenda-setting of their industry from other stakeholders [8]. EMS

standards (ISO 14001) was an important step in the development of modern environmental

regulation [5].

Self-regulatory mechanisms, including the ISO 14000 series and community engagement

processes, accept the legislative regulations as a minimum standard that industry must

achieve. Self-regulation implies (to a large extent) no legal requirement to comply, though it

is generally considered to be effective when it operates within a range of regulatory

mechanisms [9-11]. Therefore some other type of incentive for organisations to adopt such

mechanisms is required. The major initial incentive for organisations to adopt self-

regulation, including ISO 14001, is provided by the market. That is, organisations adopting

them will, it is commonly claimed by advocates, be more efficient & competitive, gaining a

long term marketing advantage.

With continuous additions and changes to regulations, it is often difficult to determine where

any particular regulator or regulation fits. One way of understanding the situation is through

the concept of a seamless web of regulation. A seamless web implies an integrated set of

regulations, regulators and incentives. Regulations involve a mix of traditional regulation

(black letter law), market mechanisms, co-regulation and self-regulation. Regulators in this

context include federal, state and local government regulators, NGO’s, peers, other

companies along the supply chain, service providers, investors, standard setting

organisations, local communities and consumers. Incentives for improved environmental

performance range from lower costs to increased market share and long term resource

access, with sanctions ranging across incarceration of directors, license withdrawal, fines,

falling profits (or surpluses), loss of market share, falling investor confidence, impacts on

reputation, social licence to operate and loss of resource access [12].

The literature suggests that greater use of multi-sectoral stakeholder forums for the

governance of complex environmental and community impacts can bolster the legitimacy of

both the industry and its regulatory regime, including those aspects handled through self-

regulation [13]. Where there are combinations of government regulation, industry self-

regulation, and regulation by multi-sectoral networks of stakeholders, self-regulation tends

to be most effective, which has been demonstrated in the Eastern Australian context [13].

Penalising companies in emerging business sectors by enforcing black letter law more

appropriate for previous generations (of an industry) is not a viable situation. Self-

Page 6 of 22

regulation, on the other hand, when demonstrated as effective, and that can be relied upon,

can assist a new industry such as renewable (or clean) energy, to establish itself without

incurring the unnecessary burden of over-regulation. This case is further argued in detail

elsewhere [14].

CONCLUSIONS

Impacts from the case study development were primarily short term in nature including

dust, obtaining a balance between weeds and bare ground, fauna impacts, transportation

and logistics relating to getting materials to the site, managing the potential for fire and

managing the end of life packaging materials (EOLPMs). Interestingly noise and visual

impacts were not found to be issues at the case study site even though the planning stages

clearly identified these as high risk areas for the project’s development. The community

consultation and related processes including complaints and incident management, were

effective under the regime used in the case study. Overall there were high levels of

regulation on the case study project though the actual impacts were relatively low.

In the case study, 296 consent conditions were placed on the construction of the USSE

Solar PV development, the majority of these relating to infrastructure and camp issues,

environmental controls during construction, and community consultation. This is relatively

high particularly as LNG plant developments, generating orders of magnitude more energy,

were regulated by approximately 550 consent conditions in Western Australia [15]. Other

solar PV sites also have a similar number and types of consent conditions to the current

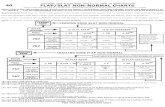

case study project [16]. Figure 1 illustrates these differences showing a proposed shift

needed in regulatory intensity in relation to new clean energy generation development and

construction.

While regulatory controls for any industry is important, the submission author makes the

point here that the setting of a project as a State Significant Development (because of its

capital investment requirement of $AUD 30 million or greater) does not necessarily mean

that the same intensity of controls should be placed upon renewable energy developments

as a new fossil fuel electricity generating plant.

The submission author recommends that:

(1) the renewable energy sector seek more favourable approval conditions such as pre-

approval for selected potential impact areas, to reduce the regulatory burden on the

sector and to encourage the adoption of further self-regulation; and

Page 7 of 22

(2) that Australian governments at all levels, including the NSW State Government,

actively engage with the renewable energy sector to reduce the regulatory burden

experienced in renewable energy infrastructure development.

While only part of the overall challenge and constraint to the adoption of clean energy

technology in Australia, the environmental and community regulatory burden is

nevertheless an area that can be improved to assist in the uptake of renewable energy and

investment in the sector.

Page 8 of 22

Table 1. Planning and Approvals (Consent Conditions) on the Case Study Construction Project and Their Ownership

General Approval Conditions

Specific Groupings of Approval Conditions No. Conditions

General Administrative conditions

Obligation to minimise harm to environment; Staging of project; Structural adequacy (of buildings); Compliance awareness (of staff, contractors, visitors); Dispute resolution

19

Environmental Performance

Health, safety and facility (infrastructure) placement issues; Camp management issues (i.e. offsite)1

32

Fire and bushfire management 2

Dangerous goods, chemical and spill management 3

Dust and air quality2 1

Water quality 2

Soil and water management3 9

Waste management & resource use 11

Utilities including powerline installation 1

Flora management including groundcover and weed management5 2

Fauna management including snake capture and relocation 1

Visual amenity protection (tree planting) 8

Noise management including controls 20

Traffic and transport management eg onsite vehicle speeds, loading routes for logistics, modification to site entry4

42

Aboriginal and European heritage management 9

Perimeter fencing including bird strike prevention 1

Environmental management and reporting

Environmental Representative (statutory role on state significant developments in planning jurisdiction)

7

Page 9 of 22

General Approval Conditions

Specific Groupings of Approval Conditions No. Conditions

Construction environmental management plan (CEMP) 36

Operational environmental management plan (OEMP) 15

Biodiversity Offset Management Plan (BOMP) 35

Traffic management plan for offsite roads 12

Incident reporting 1

Regular reporting (including project updates, community consultation reports)

1

Community Consultation 11

Complaints6

10

Compliance tracking6

6

Cumulative effects 1

Notes:

1. Camp management: A camp located in the nearest township provided housing 10 km away from construction site in local community. Housed up to 250 personnel during peak construction. Health and safety was in relation to the camp setting and environment.

2. Dust: Compliance to approval conditions required daily carting of water from source to work front. There were two events where the dust levels were so high on site, works had to be shut down resulting in downtime and costs for the EPC. The soil type was a red clay loam. Actual tests undertaken on soil from the site revealed that the fine fraction of <1 mm represented 44% of the soil fraction, revealing a high susceptibility to wind-blown dust generation. The broader issue of air quality i.e. vehicle emissions, was considered and evaluated as a “low” risk. The “very high” ranking for non-conformances was due to the dust interfering with workers on the work front.

3. Soil and water management: Though there were no significant risks in meeting the compliance requirements for soil management, compliance to water management was extensive, requiring the purchasing and recording of all water usage and of water transport from local licence holder. Earthworks valuing $250,000 were undertaken even though the actual flood risks were relatively low and equivalent to 1:100 to 1:200 year flood risk. Erosion and sediment control was expected to be an important risk at the site however this was not found to be the case during construction.

4. Traffic and transport: The majority of the costs (approximately $240K) were associated with making the entrance to the site safe with respect to main road traffic interactions. The relatively high non conformances were primarily due excessive speed of vehicles travelling on the site.

5. Flora: The majority of costs were those associated with application of knock-down herbicide, slashing and mowing of grass within the construction footprint (under and immediately around the Solar PV arrays). These costs will vary according to climate and soil type. Spreading of weeds was not identified as an issue until 12 months into the construction stage.

6. Observed non-conformances: It is noted that non-conformances are self-reported as observed during daily, weekly and monthly inspection and hazard reports from site personnel. Low = <10 reports; M= 10-100 reports; H= 100-200 reports; VH = >200 reports.

Page 10 of 22

Table 2. Observed Versus Expected Planning and Approvals Risks

General Approval Conditions

Specific Groupings of Approval Conditions

No. of Conditions

Owner vs EPC Responsible

Risk Profile2

Cost Estimate1

Expected Risk (HAZID Process)

Observed Risk9

Complexity of Integrationof controls

Observed Non-conformances8

General Administrative conditions

Obligation to minimise harm to environment; Staging of project; Structural adequacy (of buildings); Compliance awareness (of staff, contractors, visitors); Dispute resolution

19 Owner L L M-H M-H L

Environmental Performance

Health, safety and facility (infrastructure) placement issues; Camp management3 issues (i.e. offsite)

32 EPC L M-L H H H

Fire and bushfire management 2 EPC L M VH L-M H

Dangerous goods, chemical and spill management

3 EPC L M M-L L M

Dust and air quality4 1 EPC L H VH VH VH

Page 11 of 22

General Approval Conditions

Specific Groupings of Approval Conditions

No. of Conditions

Owner vs EPC Responsible

Risk Profile2

Cost Estimate1

Expected Risk (HAZID Process)

Observed Risk9

Complexity of Integrationof controls

Observed Non-conformances8

Water quality 2 EPC L M VL VL VL

Soil and water management5 9 EPC H M H H H

Waste management & resource use 11 EPC H L VH H-VH VH

Utilities including powerline installation

1 Owner L M M L L

Flora management including groundcover and weed management7

2 EPC L M VH H VH

Fauna management including snake capture and relocation

1 EPC L M VH M-H M

Visual amenity protection (tree planting)

8 Owner L L VL VL VL

Noise management including controls

20 EPC L M-H L M M-L

Page 12 of 22

General Approval Conditions

Specific Groupings of Approval Conditions

No. of Conditions

Owner vs EPC Responsible

Risk Profile2

Cost Estimate1

Expected Risk (HAZID Process)

Observed Risk9

Complexity of Integrationof controls

Observed Non-conformances8

Traffic and transport management eg onsite vehicle speeds, loading routes for logistics, modification to site entry6

42 EPC H M M-H H H

Aboriginal and European heritage management

9 EPC L M VL VL L

Perimeter fencing including bird strike prevention

1 EPC L M L L L

Environmental management and reporting

Environmental Representative (statutory role on state significant developments in planning jurisdiction)

7 EPC/Owner L H H L L

Construction environmental management plan (CEMP)

36 EPC/Owner L M H M L

Page 13 of 22

General Approval Conditions

Specific Groupings of Approval Conditions

No. of Conditions

Owner vs EPC Responsible

Risk Profile2

Cost Estimate1

Expected Risk (HAZID Process)

Observed Risk9

Complexity of Integrationof controls

Observed Non-conformances8

Operational environmental management plan (OEMP)

15 EPC L H H H L

Biodiversity Offset Management Plan (BOMP)

35 Owner/EPC L M L M L

Traffic management plan for offsite roads

12 Owner/EPC L M VL VL L

Incident reporting 1 EPC/Owner L M L M-H L

Regular reporting (including project updates, community consultation reports)

1 EPC/Owner L L L M L

Community Consultation 11 Owner/EPC L M L M L

Complaints 10 Owner/EPC L H M L L

Compliance tracking 6 EPC L H VH M M

Page 14 of 22

General Approval Conditions

Specific Groupings of Approval Conditions

No. of Conditions

Owner vs EPC Responsible

Risk Profile2

Cost Estimate1

Expected Risk (HAZID Process)

Observed Risk9

Complexity of Integrationof controls

Observed Non-conformances8

Cumulative effects 1 EPC/Owner L L VL L L

Notes:

1. Costs: These are those in excess to preparation of planning documents. High = $250k+; Low = <$250k. These are based on estimates of time input and expenses associated with the full compliance with each of the approval conditions including the production of approval documentation to comply with conditions, time and resources used during the construction phase. It excludes any costs associated with the operations and maintenance phase of the project. Single largest spend item was due to compliance to waste and resource re-use requirements.

2. Expected/unexpected priority: Groupings of approval conditions were classified according to the expected versus actual risk presented to the project, before and after the construction stages, respectively. The risk profile was calculated using the risk assessment matrix used across the project during a HAZID meeting 12 months prior to construction. Of the 27 specific condition categories, only 12 were identified during the HAZID. This is at least partly due to the fact that some of the categories were a requirement of the approval conditions and not a result of HAZID process. The risk assessment process followed the protocol described in the ISO 31000 on Risk management.

3. Camp management: A camp located in the nearest township provided housing 10 km away from construction site in local community. Housed up to 250 personnel during peak construction. Health and safety was in relation to the camp setting and environment.

4. Dust: Compliance to approval conditions required daily carting of water from source to work front. There were two events where the dust levels were so high on site, works had to be shut down resulting in downtime and costs for the EPC. The soil type was a red clay loam. Actual tests undertaken on soil from the site revealed that the fine fraction of <1 mm represented 44% of the soil fraction, revealing a high susceptibility to wind-blown dust generation. The broader issue of air quality i.e. vehicle emissions, was considered and evaluated as a “low” risk. The “very high” ranking for non-conformances was due to the dust interfering with workers on the work front.

5. Soil and water management: Though there were no significant risks in meeting the compliance requirements for soil management, compliance to water management was extensive, requiring the purchasing and recording of all water usage and of water transport from local licence holder. Earthworks valuing $250,000 were undertaken even though the actual flood risks were relatively low and equivalent to 1:100 to 1:200 year flood risk.

6. Traffic and transport: The majority of the costs (approximately $240K) were associated with making the entrance to the site safe with respect to main road traffic interactions. The relatively high non conformances were primarily due excessive speed of vehicles travelling on the site.

7. Flora: The majority of costs were those associated with application of knock-down herbicide, slashing and mowing of grass within the construction footprint (under and immediately around the SPV arrays). These costs will vary according to climate and soil type. Spreading of weeds was not identified as an issue until 12 months into the construction stage.

Page 15 of 22

8. Observed non-conformances: It is noted that non-conformances are self-reported as observed during daily, weekly and monthly inspection and hazard reports from site personnel. Low = <10 reports; M= 10-100 reports; H= 100-200 reports; VH = >200 reports

9. It is noted that the observed risks, where these were higher than medium, were reduced to medium or lower during the project.

Page 16 of 22

Table 3. Outcomes, Measures and Targets Related to Environmental Impacts from the Project

Impact Area Measure Description Target Actual Actual Measure/Quantity

Power generation/export

Rehabilitation of impacted areas during transmission line installation (%)

Land was cleared of native vegetation for array and transmission line installation

100% 100% 10 ha

Installed capacity Planned installation: 102 MW 100% 100% 102 MW±4 MW

Power generation Design power output: 233,000 MWhr 100% 100% 233,000 MWhr

Total construction footprint Area was formerly dryland cropping and sheep grazing 100% 100% 250 ha

No of posts installed Approximately 300,000 steel posts were installed 100% 100% 300,000

No of panels (modules) installed

Modules were installed on above ground posts/tables. 100% 100% 1.36 million + 3000 replacement panels

Planning and environment Objectives

Staff awareness All staff to be aware of their environmental obligations 100% 100% 800 visitors, contractors, staff

Trenching inspected Trenching was prepared for installation of AC and DC cabling 100% 100% 110 km of trenching was open in total

No of fauna deaths Fauna deaths were due to machine-fauna interactions. 0 20 1 injury was sustained by a bird (not a death)

Page 17 of 22

Impact Area Measure Description Target Actual Actual Measure/Quantity

No of Noise complaints Emanating from construction activities on the site and at the residential camp

0 0 No formal complaints received (re project)

No environmental related incidents

Zero reportable incidents. This data was extracted from the HSE incident register.

0 3 Note: numerous environmental issues were raised as hazard observations

No of non-conformances Prior to practical completion, an independent audit was conducted against approval conditions

0 5 Non-conformances were raised in audit

Community consultation meetings

All planned meetings to occur. 100% 100%

Community complaints Complaints related to any aspect of the project construction stage

0 2 Complaints related to off-site issues

Compliance to complaint response time frames

Close out process for individual complaints 100% 100% All completed

Environmental Representative (ER) inspections

These were scheduled on a monthly basis 100% 100% ER worked independently to project

Number of Hollow Bearing Trees (HBT) protected

Hollow bearing trees (HBTs) were expected to be disturbed during the construction stage.

100% 100% Approximately 50 habitats were impacted. These were offset by 166 nest boxes and hollows

Page 18 of 22

Impact Area Measure Description Target Actual Actual Measure/Quantity

Waste to landfill Waste generated from office activity including food scraps 0 15-20 t No local council recycling services provided

% panels/modules returned to manufacturer

1.36 million solar PV panels/modules were installed 100% 100% 3000 disused modules returned to manufacturer

Compliance to audit timeframes

Inspections and completion of corrective actions 100% 80% Audits and inspections were conducted weekly, monthly and at 6-12 month (external)

Fauna relocations and release

Snakes and reptiles were to be relocated to less hazardous i.e. non-work areas

100% 95% Approximately 20 snake releases occurred

Nest sites of the Grey-crowned babbler (GCB) protected

These were the only endangered species identified as living in the construction area

100% 100% 3 potential nests (of GCBs) were identified and relocated

Number of nest box types (species targeted)

Five different bird species (including the GCB) were identified as living in the construction area

100% 80% 4 out of 5 types of recommended nest boxes were constructed and placed in adjacent off set area

Page 19 of 22

Notes:

1. It was noted that the two complaints were not project related.2. Only 20 t of office waste and 100 t of construction wastes (mainly used concrete), totaling 120 t out of a larger 2000 t from EOLPM, were sent to landfill.3. A relatively small number (3000) of modules were identified as broken during construction and immediately after practical completion of the construction

stage (due to cracking from excessive pressure on installation and or physical damage).4. A total of 296 approval conditions were applicable to the site during the construction stage of the development.

Page 20 of 22

Page 21 of 22

Figure 1. A proposed shift in regulatory intensity for clean energy projects

REFERENCES

1. Anonymous. Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA). 2016 [cited 2016 7 October 2016]; Available from: http://arena.gov.au.

2. Lyster, R., et al., Environmental and Planning Law in New South Wales. 2012, Sydney, New South Wales: The Federation Press.

3. Steinzor, R.I., Reinventing Environmental Regulation: The Dangerous Journey from Command to Self-Control. Harv Environ Law Rev, 1998. 22(1): p. 103.

4. Neale, A., Organising Environmental Self-Regulation: Liberal Governmentality and the Pursuit of Ecological Modernisation in Europe. Environ Politics, 1997. 6(4): p. 1.

5. Altham, W.J. and T.F. Guerin, Where does ISO 14001 fit into the environmental regulatory framework? Australian Journal of Environmental Management, 1999. 6(2): p. 86-98.

6. Gunningham, N., Environment, Self-Regulation, and the Chemical Industry: Assessing Responsible Care. Law & Policy, 1995. 17(1): p. 57-109.

7. Guerin, T.F., A case study identifying and mitigating the environmental and community impacts from construction of a utility-scale solar photovoltaic power plant in eastern Australia. Solar Energy, 2017a. 146: p. 94-104.

8. Campbell, J.L., Business Associations and Industrial Self-Regulation: When Do Corporations Organize Collectively? Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP). 1988.

9. Aalders, M., Regulation and In-Company Environmental Management in the Netherlands. Law & Policy, 1993. 15(2): p. 75-94.

10. Bomsel, O., et al., Is There Room for Environmental Self Regulation in the Mining Sector? Resources Policy, 1996. 22(1-2): p. 79-86.

11. Rehbinder, E., Environmental Agreements-a New Instrument of Environmental Policy. Environ Policy Law Aug, 1997. 27(4): p. 258.

12. Altham, W.J. and T.F. Guerin, Environmental self-regulation and sustainable economic growth : The seamless web framework. Eco-Management and Audit - Journal of Corporate Environmental Management, 1999. 6(2): p. 61-75.

13. Boutilier, R.G. and L. Black, Legitimizing industry and multi-sectoral regulation of cumulative impacts: A comparison of mining and energy development in Athabasca, Canada and the Hunter Valley, Australia. Resources Policy, 2013. 38(4): p. 696-703.

14. Guerin, T.F., Evaluating expected and comparing with observed risks on a large-scale solar photovoltaic construction project: A case for reducing the regulatory burden. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017b. 74: p. 333-348.

15. Guerin, T.F., Best Practise Matters. Ethical Investor, 2012. April(99): p. 21.16. Anonymous. NSW Planning 2016; Available from: http://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/.

Page 22 of 22