Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

-

Upload

paijo-tengkleng -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

1/11

Incorporating community objectives in improved wetland management:the use of the analytic hierarchy process

Gamini Herath*

School of Business, La Trobe University, Albury/Wodonga Campus, Wodonga, Vic. 3690, Australia

Received 7 May 2003; revised 3 November 2003; accepted 9 December 2003

Abstract

Wetlands in Australia provide considerable ecological, economic, environmental and social benefits. However, the use of wetlands has

been indiscriminate and significant damage to many Australian wetlands has occurred. During the last 150 years one third of the wetlands in

Victoria have been lost. A conspicuous problem in wetland management is the paucity of involvement by stakeholders. This paper uses the

Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to incorporate stakeholder objectives in the Wonga Wetlands on the Murray River. The study shows that

the AHP can explicitly incorporate stakeholder preferences and multiple objectives to evaluate management options. The AHP also provides

several approaches for policy makers to arrive at policy decisions.

q 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Wonga wetlands; Analytic hierarchy process; Stakeholder; Community; Management

1. Introduction

Wetlands provide important ecological, economic, and

social benefits such as improved water quality, flood

control, reduced nutrient pollution and habitat for a diversity

of plants and animals and recreational opportunities and

economic benefits to rural communities. However, many

wetlands in Australia have been destroyed or degraded due

to unsustainable use patterns. Not a single wetland in the

Murray region is in its natural condition (Lugg, 1993).

During the last 150 years, one-third of the wetlands in

Victoria were lost and in the Murray River, over 35% ofseasonally inundated wetlands are now degraded (Pressey,

1986; Bennett, 2000).

The major constraints to proper management of wetlands

are (a) excessive focus on technological approaches that

alter the environment (b) lack of knowledge of different

stakeholders (e.g. farmers, conservationists, recreationists,

etc.) and their values and attitudes (c) conflicting multiple

objectives of stakeholders and (d) difficulties in quantifying

economic, environmental and recreational values. All these

problems reflect the non-involvement of stakeholders

in decision-making. An inclusive process that reflects

community interests and provides them with a key role in

influencing planning and management decisions will have a

greater chance of success.

Community involvement would provide policy alterna-

tives that are more acceptable to the community. If

stakeholders are adequately represented in decision-making

allowing them to cooperate in an honest and open exchange

of views, it is possible to reach agreed positions and

minimise conflicts, provide in-built controls and incentives

for conservation and sustainable use, help reduce negative

environmental effects and increase the sustainability of

wetlands (Wright, 1997). Participation enhances the legiti-macy of the process and conveys to the public the

complexities of policy making and the limits of government

capacity to respond to public needs and demands.

Yet, community participation in wetland management in

Australia has been limited to discussions with community

leaders or comments on plans prepared elsewhere and

stakeholders have little role in identifying issues, develop-

ing alternative management options and prioritising

choices. Hence, wetland management in Australia is in a

state of flux. The existing institutions are becoming strained

and less able to perform their historical function of

mediating competing demands of wetland services. Today,

stakeholders such as recreational users, anglers, logging

interests, environmentalists all compete among themselves

0301-4797/$ - see front matter q 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2003.12.011

Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273www.elsevier.com/locate/jenvman

* Tel.: 260583837; fax: 260583833.

E-mail address: [email protected] (G. Herath).

http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jenvmanhttp://www.elsevier.com/locate/jenvman -

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

2/11

for the stressed wetland systems. The key to successful

wetland management is gaining a thorough understanding

of the people and ecological processes unique to wetland

systems and using this understanding in the design and

implementation of appropriate management strategies.

The realisation that traditional technocratic approaches

may be incurring unnecessary costs and may not be

optimising the benefits of wetland management has opened

the door for the application of new concepts. By investing

up front in understanding the wetland systems, costly

mistakes and restoration measures may be avoided in the

future. Wetland management is evolving into a multi

objective management approach. Technical issues will not

dominate decision-making but will provide inputs to a more

democratic process of negotiations among various stake-

holders. No single group such as irrigators, anglers,indigenous users control the agenda and the management

agencies. The diffusion of power among a multitude of

stakeholders means that agencies have increasingly less

power to resolve conflicts by imposing a solution. An

approach that can provide explicit information about

community objectives, their tradeoffs and attitudes means

that the conflicts can be better understood (Turner et al.,

2000). Several participatory methods including question-

naire surveys, telephone surveys, community workshops,

public meetings, public comment opportunities have been

used but have been criticised as inadequate. Most of theseexercises have been information gathering exercises rather

than explicit involvement in decision-making.The main difficulty in implementing participatory

approaches is the lack of tested methods, which could

facilitate stakeholder negotiations and allow greater ana-

lytical rigour. New techniques of multi-criteria decision

analysis (MCDA) have been found to be particularly useful

for improved wetland management. MCDA can simplify

and structure the wetland management problem, facilitate

explicit incorporation of multiple values and preferences of

stakeholders in decision-making (RAC, 1992). A number of

applications of MCDA have been reported in Australia.

Assim and Hill (1997) applied MCDA techniques to

evaluate alternative water management plans in the

Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area and Districts. They foundMCDA to be useful in resolving tradeoffs between

economic and environmental goals. Deng et al. (2002)

used the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to evaluate

tourism attributes in Victorian Parks in Australia. They

ranked 36 selected state and national parks in Victoria into

four levels, ranging from Grade 1 to Grade 4. Qureshi and

Harrison (2000) used AHP to evaluate four riparian

vegetation options for the Johnston River Catchment in

North Queensland with five stakeholder groups. The use of

prompt cards for pairwise comparisons is an innovative

feature of this study. Proctor (2000) applied AHP to regional

forest planning in Australia. The study focused on

the Southern New South Wales forest region. Proctors(2000) study revealed that the two extreme forest use

optionsthe conservation option and the timber industry

option are preferred over the middle ground options.

The specific objectives of this paper are to:

Identify different stakeholder groups in the Wonga

wetlands in the Murray River;

Identify stakeholder objectives in wetland use;

evaluate the relative importance of these objectivesamong stakeholders using the AHP and

incorporate these public values into wetland manage-

ment options to develop better management strategies.

2. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA)

MCDA refers to a suite of techniques in which multiplevalues reflecting different objectives are quantified and used

to provide a decision outcome, which reflects objectives

broader than just economic objectives (Gregory, 2000). The

important advantage of MCDA is that it can account for

multiple criteria of assessment rather than a single criterion

such as dollar values. The emphasis on MCDA alters

wetland management from one that is dependent on

hardware to one that depends on information. MCDA is a

rational decision-making framework, which explicitly

incorporates multiple objectives of decisions makers.

MCDA improves communication and understanding

among multiple decision makers and facilitate ways of

reaching policy compromises. MCDA is concerned withsolving problems where there is a set of proposed options

and several conflicting objectives. It allows the decision

makers to rank objectives, resolve conflicts and identify

areas of importance. It can be applied to a variety of

environmental problems characterised by multiple goals.

MCDA is a promising framework for evaluation sincethey have the potential to take into account conflicting,

multidimensional, incommensurable and uncertain effects

of decisions explicitly (Carbone et al., 2000; Munda, 2000;

Omann, 2000). The most widely used multi-criteria

methods include the AHP, Multi-attribute Utility Theory

(MAUT), Multi-criteria Value Functions (MCVF), out-

ranking theory and goal programming. The MAUT hasshortcomings. Russell et al. (2001) found mixed empirical

evidence about whether MAUT improved the internal

consistency of preference surveys. MAUT also assumes

that decision alternatives follow a known probability

distribution. The AHP has been widely applied for

preference analysis in complex, multi-attribute problems

(Varis, 1989).

2.1. The analytic hierarchy process

The AHP, developed by Saaty (1980) is a mathematical

method for analysing complex decisions. It is a general

theory of ratio scale measurement based on mathematicaland psychological foundations (Kangas, 1993). The AHP is

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273264

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

3/11

not grounded on any specific theoretical basis such as neo-

Paretian welfare theory. What it does is to aggregate the

separate performance indicators into an integrated perform-

ance indicator (Bouma et al., 2000). The AHP facilitates a

rigorous definition of priorities and preferences of decision

makers and is useful in analysing decisions involving many

stakeholders and multiple objectives (Saaty, 1980).

In the case of wetlands, the overall goal is to achieve

sustainable management. Criteria are then defined by which

each option should be considered in meeting the objectives.

Each criterion can have sub-criteria. Many options can be

constructed each containing different levels of criteria that

contributes to the overall objective. The AHP is based upon

the construction of a series of pairwise comparison

matrices, which compares criteria to one another. Selected

stakeholders are asked to carry out the pairwise comparisonsof the identified criteria and sub-criteria. Each cell reveals

the relative importance of an attribute compared to another.

The quantitative weights for criteria are based on the

decision makers qualitative comparison of all pairs of

criteria. This provides a ranking or weighting of each of the

criteria that describes the importance of each criterion to the

overall objective. Weights to these sub-attributes are

assessed using pairwise comparisons. The method is

interactive where a stakeholder or a group of stakeholders

indicate their preferences to the analyst. In this approach,

the objectives of stakeholders are identified (e.g. biodiver-

sity conservation, recreation, economic activities etc.)

which may be further subdivided into a number of sub-

criteria, and the pairwise comparison is repeated for each

level of the hierarchy.

In AHP data are obtained from the decision makers

through pairwise comparisons among the elements at one

level of the hierarchy with respect to an element in the next

higher level. In making the comparisons, it is a question of

which of the two attributes is more important and how much

more important. The decision maker has the option of

expressing his or her intensity of preference on a nine-point

scale (Table 1). If two criteria are of equal importance, a

value of 1 is given in the comparison, while 9 indicates the

absolute importance of one criterion over the other. Withineach hierarchy there are three types of comparisons:

(a) major categories are compared with each other, (b)

criteria within these categories are compared to each other

with respect to the categories, and (c) alternatives are

compared to each other with respect to each criterion. The

overall weights for each alternative are computed from the

priority vectors of individual comparison matrices. AHP can

deal with qualitative attributes as well as quantitative

attributes. When applying AHP, a hierarchical decision

schema is constructed by decomposing the decision

problem into its decision elements. Numerical techniques

are used to derive quantitative values from verbal

comparisons (Kurttila et al., 2000).

Pairwise comparison data can be analysed using either

regression methods or the eigenvalue technique. In the

eigenvalue technique, the reciprocal matrices of pairwise

comparisons are constructed. Using these pair wisecomparisons, the parameters can be estimated. The right

eigenvector of the largest eigenvalue of matrix A constitutes

the estimation of relative importance of attributes (Eq. (1)),

where bi is the importance or desirability of decision

element i: In the AHP approach, the eigenvector is scaled to

add up to 1 to obtain the weights.

A aij

1 b1=b2 b1=bn

b2=b1 1 b2=bn

bn=b1 bn=b2 1

0BBBBBBBBB@

1CCCCCCCCCA

1

Based on properties of reciprocal matrices, a consistency

ratio (CR) can be calculated. Saaty (1977) has shown that

the largest eigenvalue, gmax; of a reciprocal matrix A is

always greater than or equal to n (number of rows or

columns). If the pairwise comparisons do not include any

inconsistencies, gmax n: The more consistent the com-

parisons are, the closer the value of computed gmax to n: A

consistency index CI, which measures the inconsistencies of

pairwise comparisons is given in Eq. (2).

CI gmax 2 n=n2 1 2

A consistency ratio (CR), given in Eq. (3), measures thecoherence of the pairwise comparisons.

CR 100CI=ACI 3

where ACI is the average consistency index of the randomly

generated comparisons. As a rule of thumb, a CR value of

10% or less is considered as acceptable.

The AHP offers a methodology to compare the

publics relative values for conservation, recreation and

business attributes of wetlands. The methodology has

been extended to enable the use of AHP in group

decision-making where the single decision maker is

actually a group of people. AHP is an easier technique

com pared t o M AUT and t he r es pons es are l essdemanding.

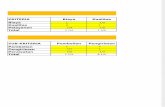

Table 1

Measurement scale of AHP

Intensity of relative importance Definition

1 Equal importance

3 Weak importance of one over the other

5 Essential or strong importance

7 Demonstrated importance

9 Absolute importance

2, 4, 6 and 8 Intermediate values between

two adjacent judgements

Source: Saaty (1977).

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273 265

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

4/11

Duke (2002) used AHP to examine public preferences for

the environmental and agricultural attributes of farmland.

There exist relatively few applications of AHP to environ-

mental or natural resource problems. AHP is not a

statistically based procedure and theoretically a sample

size of one is enough to implement the AHP. Many studies

used small number of experts or professionals. Peterson et al.

(1994) used five respondents. Mawapanga and Debertin

(1996) used 18 participants. This paper uses a large sample

of stakeholders to investigate the preferences for wetland

attributes and rank alternative management options.

3. Application of AHP

The practical application of AHP involves (a) structuringthe decision problem (b) identifying management options

(c) identifying criteria (d) identifying the stakeholders and

(e) developing the weighting schemes and ranking manage-

ment options. These are briefly discussed in the sections

below.

3.1. Identifying stakeholders

Stakeholders share a common interest or stake in the

wetland. Stakeholders include policy makers, planners,

administrators and others. The process of selection of

stakeholders has to be open and transparent (Buchy

and Hoverman, 2000). Grimble and Chan (1995) suggestthat stakeholders be initially identified through reputation,

focus groups or demographic analysis. Harrison and Quershi

(2000) suggest that the selection process should not be

one-shot approach, but rather an iterative approach, where

discussions with pre-identified stakeholders reveal other,

previously unknown stakeholders. They also question the

relevance of probability sampling in multicriteria analysis,

where a greater recognition is given to qualitative aspects of

the decision problem. A very large number of stakeholder

groups however, make the elicitation exercise difficult

(Harrison and Qureshi, 2000).

3.2. Structuring the decision problem

Identifying the stakeholders and structuring stakeholder

objectives in wetland management require careful empirical

investigation. Focus must be both on fundamental objec-

tives, which are the attributes that stakeholders genuinely

care about, and means objectives, which are ways to

accomplish the fundamental objectives (Keeney, 1992).

Objective hierarchies can be constructed using thisclassification.

3.3. Identifying management options and criteria

Management options are the available alternative actionsthat achieve some or all of the objectives of the decision

problem. Often they are represented as discrete choices for

easy evaluation. They can be identified from the policy

documents or constructed to represent the stakeholder

values (Keeney, 1992). Identifying a set of criteria or

attributes is critical to evaluate preferences and alternative

management plans. The criteria need to be reduced to a few

key criteria, representing the major tradeoffs involved in any

empirical application of the model. Participatory tools such

as In-depth Groups (De Marchi et al., 1998), Negotiation

Forums (Eastman et al., 1998), Focus Groups (Keeney et al.,

1990; McDaniels and Roessler, 1998), and Citizens Juries

(Crosby, 1996) can be effectively employed to elicit the

most important criteria for a particular wetland. The main

criteria could be aesthetic, environmental conservation,

recreation, economic, social and cultural values.

3.4. Weighting schemes

Once the decision schema and stakeholder groups are

chosen, the weights and preferences of different stakeholder

groups should be determined. Two scenarios can bedeveloped (a) equal weights for all stakeholders or (b)

unequal weights for stakeholders. In the case of unequal

weights, the weights can be obtained from stakeholder

groups themselves (self-assessed weights) or they can be

determined by the government authority in charge of

wetland management or assumed values used in combi-

nation with sensitivity analysis.

In group decision-making, Aczel and Saaty (1983)proved that the geometric mean is consistent with conditions

for synthesis of judgments. If we have m individuals, acomposite judgment of their weights is the geometric mean.

Using geometric means, a set of numerical values can be

calculated to represent the relative degree of importance

among the decision attributes. Also a set of numerical values

can be computed to represent the relative importance of

several individual judgments.

4. Application of AHP to Wonga wetlands

4.1. The Wonga wetlands

The Wonga wetlands on the Murray River in Australia is

a relatively small wetland but significant for its specific

features. It has 108 ha including 80 ha of lagoons and

diverse range of flora and fauna and limited recreational

opportunities. The River Red Gum is a significant feature of

the Wonga wetlands. In year 2000, nearly 110 bird species

were sighted in the wetlands. During winter the Wonga

wetland fills, from both the natural catchment but primarily

from the wastewater treatment plant in Albury (which is a

unique feature of the Wonga wetland). Many vertebrate

species breed in the ephemeral areas, but in summer the

wetland dries out which is important for waterbird breeding.In winter, the wetlands act as a reservoir to ensure that no

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273266

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

5/11

water is discharged into the Murray River. Visits to the

wetlands are presently restricted for educational institutions

and registered interest groups such as bird observers, field

naturalists, photography/bushwalking groups (Wonga Wet-

lands, 2001). These groups have availed themselves of this

opportunity to experience a unique ecological laboratory in

the area.

Plans are underway for some nature-based investments inthe Wonga wetlands such as nature trails around the lagoon

boardwalks, reception centre, bird hides, aboriginal camp-

sites, and an interpretive centre. The proposed investments

will cost several million dollars. Funds are being sought

from the business community in Albury/Wodonga for these

investments. The aim of these investments is to increase

tourism flows and enhance nature-based experiences. They

are also expected to generate an ecologically sustainablewetland. However, the dilemma the planners are facing can

be easily understood from the following: A critical issue is

to consider how to make this facility available to all those in

the community who want to share the experience of a

reconstituted riverine wetland, whilst minimising disturb-

ance to the flora and fauna and any other adverse effects of

these investments. (Wonga Wetlands, 2001). This state-

ment reflects that the wetland management problem is a

classic multi-attribute problem that can benefit from

MCDA.

4.2. Formulating the decision problem

Many wetland management options can be developed

which are different combinations of the criteria, whichcontribute to the attainment of the objectives of stake-

holders. The existing option can be used as the base case to

assess the other alternative options. The existing option is

where no investments have been made as yet and 100% of

the conservation value of the wetland is preserved and 2000

recreation visitor days are available.

The decision problem was cast as one involving the

choice of the best wetland management plan for Wonga

wetlands that optimally satisfies the stakeholders. Focus

group interviews were conducted to obtain preliminary

information on (a) different types of stakeholders (b) majorattributes of importance to stakeholders (c) wetland

management options and (d) criteria to assess these

alternative options. The focus groups revealed conservation,

economic (any commercial advantages arising from adver-

tising due to contributions made towards the investments

referred to above) and recreational benefits by actually using

the wetlands for visiting, walking etc. to be the three major

objectives of stakeholders. The conservation objective

reflects the desire to protect the wetland ecology. The

investment objective reflects the desire of some to obtain

any commercial potential that may be there in the

redesigned wetland in terms of advertisements, business

promotion etc. The recreation objective would capture theexperiential dimension and learning arising from the visits

to the wetland. Each of these objectives can be reflected in

several sub-attributes as shown in Table 2. For example the

environmental attribute can be reflected in terms of the

number of species of birds or the presence of the River Red

Gum trees.

Table 2 presents a useful objective hierarchy for the

Wonga wetlands developed by examining relevant docu-

ments, consultation with officials in the Albury City council

and the focus group interviews. A decision model for the

problem is given in Fig. 1. The model contains four levels:

the most general objective of wetland management and

planning is considered as maximising overall utility at level

1. Level 2 consists of stakeholder groups. Three main

stakeholder groups namely the conservation group (main

objective is conservation of the wetland), and recreational

user group (would like to maximise the recreational benefitsfrom the wetland) and small business groups (would like to

benefit by providing investment funds to the City Council)

are considered the most relevant for this analysis. Level 3

gives the attributes of the decision problem. The attributes

can be further subdivided into more detailed decision

attributes. For example, the decision attribute wetland

conservation could be decomposed into the extent of old

River Red Gum reserved and/or the number of bird species

protected. Level 4 consists of alternative wetland manage-

ment options, which are different combinations of the three

decision attributes.

When there are a large number of indicators, pairwise

comparisons may become tedious to the respondent andhence only the three most important attributes are

considered. Hence only three indicators, one for each

attribute was used for the options in order to keep the

respondents task manageable. The attributes chosen for the

conservation attribute was the percent of bird species. Only

three management options were constructed for evaluation

although theoretically many options can be developed.

These were constructed taking into account the status quo as

the base case (Option 1). The second option involved

reducing the conservation objective and adding the business

and recreation objectives as well. Some subjectivity is

involved here and this was due to the non-availability of anyinformation on the trade offs involved among the three

attributes. Thus a linear relationship is assumed among

Table 2

An objective hierarchy for the Wonga Wetlands

Aim Goals Criteria

Sustainable

management

of wetlands

Economic goals Investment (returns from advertising

and promotional effects)

Conservation goals Ecosystem conservation protection

of fauna and flora species

Water qualityRecreational goals Visits educational values

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273 267

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

6/11

the three attributes. Any business investment is considered

to lead to a decline in the bird population and increase in

visitor numbers and many respondents concurred with this

observation. Changes were made to the base plan to obtain

the other two options.1 A million dollar investment isconsidered 100% investment. An arbitrary 100% increment

in investment was made in option 2 and this was assumed yo

cause a 25% decline in the conservation value but will

increase the number of visits to 5000. This is because

business investment will produce other attractions as well

and also will remove any limitations currently imposed on

visitor numbers. While the direction of change in the

attribute levels is logical, the extents are not since not much

information is available to use a more objective approach.

These can however be refined as and when more

information is available.

The number of bird species reflected conservation value,

recreation is measured using recreation visitor days and

investment is measured in terms of dollars but the indicator

was the percent investment (one million dollars investment

is considered 100% investment). Table 3 summarises the

wetland management options hypothesised for the Wonga

wetlands.

4.3. Survey procedure

Two hundred and sixty residents of Albury/Wodonga

selected on a stratified random basis (stratified according to

particular interest) were interviewed to reveal theircollective preferences for the Wonga wetlands using a

pre-tested questionnaire. The pairwise questions were

presented as follows:

Preserving bird species is 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

more important than business investment

Business investment is 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

more important than preserving bird species

4

The respondent is asked to choose the attribute that

should be given more importance (or priority) and then to

circle the appropriate strength of preference (either on the

first or the second line) after referring to either the verbal or

numerical preference scale. Then the attribute levels of the

three hypothetical options were compared pair wise with

respect to one attribute at a time. For example, the pairwise

comparison of option 1 (OPT 1) and option 2 (OPT 2) with

Fig. 1. A decision model to evaluate wetland use options.

Table 3

Wonga Wetlands management options

Indicators Option 1 Option 2 Option 3

Conservation value 100% 75% 90%

Business investment ($ million) Nil $1.0 0.5

Recreation visitor days 2000 5000 3500

Extent of river red gum (percent area) 100% 75% 90%No. of bird species 110 82% 99%

1

Alternative management strategies can be based on simulation andoptimising models (Kangas et al. 2000) and they should take technical

feasibility and national reserve criteria into account.

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273268

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

7/11

respect to conservation is as follows:

OPT 1 is 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 more important than OPT 2 or

OPT 2 is 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 more important than OPT 1

5

The above procedure is repeated for the other two

attributes. An impact table or effects table, which details the

consequences associated with the chosen level of decision

attributes, is often used when making pairwise comparisons

(Proctor, 2000). However, in this study development of a

comprehensive impact table was not feasible mainly due to

lack of data on critical inter-relationships.

A total of 221 usable questionnaires were analysed. Some

of the questionnaires wereremoved from the analysis because

of interviewer perceptions that they were not satisfactory orthatthey areincomplete. Theconservation-orientedgroup was

the largest with a total of 120 respondents; the business group

came second with 65 respondents. The recreation group had a

total of 36 respondents. The selection was made using the

telephone directory for Albury/Wodonga. Each respondent

was asked to classify himself into an appropriate group and

this was used as the basis to allocate a given respondent into a

particular group. Many of the respondents knew the Wonga

wetlands and were aware of wetland functions. The survey

also revealed that the investment plan of the city council was

known by around 40% and the rest were unaware of the

proposal. Most respondents found it easy to grasp the

objectives of the survey because it is a small wetland andalmost everyone knew about it and its various features. Some

respondents had difficulties in trading-off these attributes and

qualities. Some of these difficulties are normal and often arise

because some goods have public goods characteristics. After

explaining the procedure the respondents were asked to make

pair wise comparisons and rank the intensity of their

preferences.

4.4. The results

The information on attributes and options were used to

examine the preferences and goals among the population.

The analysis revealed what sort of management optionswould be acceptable to the majority and is sustainable and

how policy decisions could be modified to better suit theparticular wetland region.

4.4.1. Pairwise comparisons

Since the problem has been structured as a hierarchy, the

relations between elements in succeeding levels are

obtained by making pairwise comparisons The Expert

Choice Computer Model was used to analyse the pairwise

comparison. By using the eigenvalue technique in the AHP

(Section 2), the weights, describing the importance of each

attribute for a given stakeholder can be computed. These

values are not presented in the paper due to spaceconsiderations. The values for a particular group are then

summed and averaged over the sample to obtain the weights

given in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that overall for the business group, the

weight of the investment attribute is 0.4847 compared to

0.2544 for the visits attribute indicating that investment is

almost twice as important as the recreation objective. A

given attribute can also be compared across the differentstakeholder groups. For example, the environmental con-

servation attribute has weights of 0.2604, 0.3520 and 0.6333

for the business, recreation tourism and conservation

groups, respectively. The AHP ranks the options based

upon the pair wise comparisons. Table 5 provides the group

analysis (where combined pair wise comparison of the

groups is used) commonly referred to as the local priorities.

The local priorities and ranking of the three management

options in Table 5 show that for the business group, option 2

and option 3 are ranked first and second, respectively. For

the conservation group, option 1 and option 3 are ranked

first and second, respectively. The recreation group rankedoption 3 and option 1 as the first and the second,

respectively.

Table 4

Weights of decision objectives by Stakeholder Groups

Weights

Conservation Visits Investment

Business group 0.2604 0.2544 0.4847

Recreation group 0.3520 0.4060 0.2421

Conservation group 0.6333 0.2088 0.1578

Table 5

Local priorities and ranking for wetland alternatives by Stakeholder Groups

Alternative/group Business group Recreation

group

Conservation

group

Priority Rank Priority Rank Priority Rank

Option 1 0.2520 3 0.3110 2 0.4040 1

Option 2 0.3880 1 0.2690 3 0.2130 3

Option 3 0.3600 2 0.4200 1 0.3820 2

Fig. 2. Most preferred wetland options by groups.

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273 269

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

8/11

The ranking of wetland management options by the three

groups is given in Fig. 2. Fig. 2 gives the results of the

individual analysis where the individual pairwise compari-

sons are analysed and the results are then used to examine

the distribution of the rankings. Fig. 2 shows that for the

conservation group, close to 30% preferred option 1, 10%

preferred option 2 and 12% preferred option 3. For the

business group, 18% preferred option 2, 3% preferred

option 1 and 4% preferred option 3. In the recreation group,

9% preferred option 2, 2% option 1 and 1% option 3. When

all groups are considered together, as shown in the fourth

part ofFig. 2, 37% preferred option 1, 42% preferred option

2 and 19% preferred option 3. These results show that the

preferences for the options differ for the three groups. For

the conservation groups, the predominant choice is option 1where no investment is made and 100% of the conservation

value of the wetland is maintained. For the business group,

the most preferred choice is option 2 where the maximum

investment is made.

The ranking of the options for the total sample is shown

in Fig. 3 and Table 6. It shows that 26% of the conservation

group preferred option 1 to option 2 and 3. In the business

group, 16% preferred option 2 to option 3 and 1. Eight

percent of the recreation group preferred option 2 to option

1 and 3. When the total sample is considered 35% preferred

option 2 over option 1 and 3.

These results have important policy implications. Policy

makers can strike a better balance between competing

stakeholder interests thereby minimising conflicts. It is

interesting to note that conservation of the wetlands was

considered an overriding priority. Policy makers should

give careful consideration to the conservation effort by

further evaluating the extent of the conservation values that

must be preserved. This is particularly so because of the

small sized nature of the wetland. The business attribute was

fairly important but the recreation attribute was the least

important. This may be because alternative venues for

recreation are easily available. The research indicates that

the stakeholders should be closely involved as partners in

decision-making and incorporating their preferences

enhance the City Councils capacity to formulate better

plans. The present study should provide a useful starting

point for comparing the options for wetlands in a mean-

ingful, systematic and stakeholder-focused way.

4.4.2. Policy options

The above scenarios do not provide the policy maker the

final policy option AHP can be used to resolve such

difficulties. Here the policy makers can impose their own

preferences in obtaining the final option. In this case policy

makers can use their own relative weights for the three

stakeholder groups. These global priorities can be calculated

on the basis of these weighting schema for the stakeholder

Fig. 3. Ranking of wetland options by group.

Table 7

Global ranking of wetland options using different weighting schemes

Weighting scheme Option Rank 836

(i) Equal weighting (B:C:T) (0.33:0.33:0.33) Option 1 2

Option 2 3

Option 3 1

(ii) (0.40:0.30:0.30) Option 1 2

Option 2 3

Option 3 1

(iii) (0.53:0.23:0.23) Option 1 3

Option 2 2

Option 3 1

(iv) (0.88:0.6:0.6) Option 1 3

Option 2 1

Option 3 2

(v) (0.086:0. 828:0.086) Option 1 1

Option 2 3Option 3 2

Table 6

Ranking of wetland management options by group

Ranking Conservation

group

Business

group

Recreation

group

Total

sample

1 . 2 . 3 4 1 2 5

1 . 3 . 2 26 2 3 32

2 . 1 . 3 2 2 2 5

2 . 3 . 1 8 16 8 35

3 . 2 . 1 4 4 1 12

3.

1.

2 6 1 2 6Total 50 26 18 94

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273270

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

9/11

groups, the importance of objectives from the point of view

of the stakeholder groups and the relative priorities of

decision alternatives with respect to the objectives. Follow-

ing Kangas (1994), the global priority of a wetland

management option can be given as:

GPi X5j1

LPSGjX3k1

LPOkjLPMSik

" #( )6

where GPi is global priority of option i; LPSGj is local

priority of stakeholder group j; LPOkj is local priority of

objective k from the point of view of stakeholder group j;LPMSik is local priority option i with respect to objective k:

Table 7 gives policy outcomes for a range of different

weights for the stakeholder groups that policy makers can

assign which are called the global priorities.

We initiate the analysis assuming that a policy maker

considers all three stakeholder groups to be equally

important and hence assign equal weights of 0.33 for each

group. The global rankings show that with equal weights,

alternatives 1, 2 and 3, are ranked second, third and first,

respectively. Thus a policy maker should adopt option 3 as

the option that should be implemented. The weights are then

changed by increasing the weights for the business group to

0.4 and there is no change in the ranking due to this change.

The weight for the business group is then changed until a

change in the ranking occurs. This occurs when the weight

for the business group is raised to 0.88. At this point option 2

becomes the number one option. Hence if the policy maker

believes that the business group is very important and that

they would assign a weight of 0.88 or more, then option 2should be implemented. This is repeated for the conserva-

tion group. When the weight for the conservation group is

changed there is no change in the ranking until the weight is

increased to 0.82. Hence if the conservation group is very

important for the policy makers and that they like to assign a

weight of 0.82 or more, then option 1 becomes the best

option and should be implemented. With respect to

Fig. 4. Performance sensitivity of options (business group).

Fig. 5. Gradient sensitivity for conservation objective (business group).

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273 271

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

10/11

the recreation group no increase of the weight from an initial

equal weight scenario causes any change in the ranking.

4.4.3. Sensitivity analysis of options

Fig. 4 shows the response of the options with respect to

each objective as well as overall objective for the business

group. The y-axis in Fig. 4 gives each objectives priority

(based on the decision-makers paired comparisons). For

example, for the conservation and the recreation objective

the best choice is option 3 and it means that option 3 is the

most preferred only if we take one attribute say recreation or

conservation. For the business group, the best option is

option 2 if we take only the investment objective. Overall

the best choice is option 2.

Fig. 5 shows that when conservation has a weight of 0.2,

option 2 is the best choice, and option 3 becomes the secondchoice for the business group. However, if the weight for the

conservation attribute is 0.3, option 3 is the best choice and

option 2 becomes the second choice. The results show how

the different weights given to conservation attribute can

change the options chosen and hence the sensitivity. The

result shows that a minor change of the weight from 0.22 to

say to 0.3 causes a change in the options selected showing a

higher degree of sensitivity. If the weight changes to about

0.6, then option 3 is the best choice. The sensitivity analysis

can be repeated for the other stakeholder groups as well

although they are not all reported here. The implication of

high sensitivity is that the weights have to be more carefully

assessed because even small errors can cause major errors inthe results.

5. Concluding remarks

Quantifying stakeholder preferences in wetland manage-

ment is a complex task. This paper uses AHP in evaluating

the planning options for the Wonga Wetlands in the Murray.

The AHP permits explicit participation by stakeholders,which is important in dealing with situations where several

stakeholder groups are present. This study shows that the

conservation group will predominantly prefer option 1

where no investment is made and the wetland is maintainedin its pristine condition. The business group predominantly

prefers option 2 where maximum investment can be made.

The recreation group predominantly prefers option 3 where

some investment is also made. AHP can accommodate

policy maker preferences as shown in this study especially

where they have particular weights for the different

stakeholder groups. It was shown that if the policy makers

weigh heavily the concerns of the conservation group, and

that they are prepared to assign a high weight above 0.82,

then the policy maker should implement option 1 and no

investment on the wetland should be considered. The

success of the method depends on the way the decision

problem is structured and how the pair wise comparisons arecarried out. It also depends on the ability of respondents

providing credible answers to the questions posed. How-

ever, many empirical studies on AHP are needed before we

generalise its wider adoption.

References

Aczel, J., Saaty, 1983. Procedures for synthesizing ratio judgments. Journal

of Mathematical Psychology 27, 93102.

Assim, F., Hill, C., 1997. Multi-criteria analysisa tool for wetland

management decision making. Paper Presented to the 41st Annual

Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics

Society, Broadbeach, Gold Coast, Queensland.

Bennett, B., 2000. Hydrotherapy. Ecos 102, 2029.

Bouma, J., Brouwer, R., Van Ek, R., 2000. The use of integrated assessment

methods in Dutch water management: a comparison of cost-benefit and

multi-criteria analysis. Paper Presented to the Third International

Conference of the European Society for Ecological Economics, May

3 6, Vienna, Austria.

Buchy, M., Hoverman, S., 2000. Understanding public participation: a

review. Forest Policy and Economics 1, 1525.

Carbone, F., De Montis, A., De Toro, P., Stagl, S., 2000. MCDA methods

comparison: environmental policy evaluation applied to a case study in

Italy. Paper Presented to the Third International Conference of the

European Society for Ecological Economics, May 3 6, Vienna,

Austria.

Crosby, N., 1996. Creating an authentic voice of the people. Deliberation

on democratic theory and practice. Midwest Political Science

Association, Chicago.

De Marchi, B., Funtowicz, S., Gough, C., Guimaraes Pereira, A., Rota, E.,

1998. The ULYSSES Voyage: Report EUR 17760EN, The ULYSSES

Project at the Joint Research Centre, Ispra: European Commission.

Deng, J., King, B., Bauer, T., 2002. Evaluating natural attractions fortourism. Annals of Tourism Research 29, 422438.

Duke, J.M., Aull-Hyde, R., 2002. Identifying public preferences for land

preservation using the analytic hierarchy process. Ecological Econ-

omics 42, 131145.

Eastman, R.J., Jiang, H., Toledana, J., 1998. Multi-criteria and multi-

objective decision making for land allocation using GIS. In: Beinat, E.,

Nijkamp, P. (Eds.), Multicriteria Analysis for Land-Use Management,

Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht.

Gregory, R.S., 2000. Valuing environmental policy options: a case study

comparison of multiattribute and contingent valuation survey methods.

Land Economics 76, 151173.

Grimble, R., Chan, M.K., 1995. Stakeholder analysis for natural resource

management in developing countries: some practical guidelines for

making management more participatory and effective. Natural

Resources Forum 19, 113124.Harrison, S.R., Qureshi, M.E., 2000. Choice of stakeholder groups and

members in multi-criteria decision models. Natural Resources Forum

24, 1119.

Kangas, J., 1993. A multi-attribute preference model for evaluating the

reforestation chain alternatives of a forest stand. Forest Ecology and

Management 59, 271288.

Kangas, J., 1994. Incorporating risk attitudes into comparison of

reforestation alternatives. Scandinavian Journal of forest Research 9,

297304.

Keeney, R.L., 1992. Value-Focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decision

Analysis. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Keeney, R.L., Winterfeldt, D.V., Eppel, T., 1990. Eliciting public values

for complex policy decisions. Management Science 36, 10111030.

Kurttila, M., Pesonen, M., Kangas, J., Kajanus, M., 2000. Utilizing the

analytic hierarchy process (AHP) in SWOT analysisa hybrid methodand its applications to a forest certification case. Forest Policy and

Economics 1, 41 52.

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273272

-

7/28/2019 Incorporating Community Objectives in Improved Wetland Management the Use of AHP

11/11

Lugg, A., 1993. Wetland Management, Guidelines for Local Councils in

the Murray Region of NSW. Department of Natural Resources and

Management, Sydney.

Mawapanga, M.N., Debertin, D.l., 1996. Choosing between alternativefarming systems: an application of the analytic hierarchy process.

Review of Agricultural Economics 18, 385401.

McDaniels,T.L., Roessler, C., 1998. Multiattribute elicitation of wilderness

preservation benefits: a constructive approach. Ecological Economics

27, 299312.

Munda, G., 2000. Conceptualising and responding to complexity. Policy

research brief, no. 2. In: Spash, C., Carter, C. (Eds.), Environmental

Valuation in Europe, Cambridge Research for the Environment,

Cambridge.

Omann, I., 2000. How can multi-criteria decision analysis contribute to

environmental policy making? A case study on macro-sustainability in

Germany. Paper Presented to the Third International Conference of

the European Society for Ecological Economics, May 36, Vienna,

Austria.

Peterson, D.L., Silsbee, D.G., Schmoldt, D.L., 1994. A case study of

resource management planning with multiple objectives and projects.

Environmental Management 18, 729742.

Pressey, R.L., 1986. Wetlands of the River Murray below Lake Hume.

Proctor, W., 2000. Laying down the ladder: a typology of public

participation in Australian natural resource management. Australian

Journal of Environmental Management 9, 205218.

Qureshi, M.E., Harrison, S.R., 2001. A decision support process to

compare riparian revegetation options in Scheu Creekcatchment in

north Queensland. Journal of Environmental Management 62,

101113.Resource Assessment Commission, 1992. Multicriteria analysis as an

assessment tool. Research Report no. 6, Canberra, Australia.

Russell, C., Dale, V., Lee, J., Jensen, M.J., Kane, M., Gregory, R.,

2001. Experimenting with multiattribute utility survey methods in a

multi-dimensional valuation problem. Ecological Economics 36,

87108.

Saaty, T.L., 1977. A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures.

Journal of Mathematical Psychology 15, 234281.

Saaty, T.L., 1980. The Analytic Hierarchy Process. McGraw-Hill, New

York.

Turner, K.R., Jeroen, C.J.M., Soderquist, T., Barendregt, A., van Stratten,

J., Maltby, E., Van Ierland, E.C., 2000. Ecologicaleconomic analysis

of wetlands: scientific integration for management and policy.

Ecological Economics 35, 723.

Varis, O., 1989. The analysis of preferences in complex environmental

judgementsa focus on the analytic hierarchy process. Journal of

Environmental Management 28, 283294.

Wonga Wetlands., 2001. Unpublished Report, Albury City Council,

Albury.

Wright, P., 1997. Liquid gold: Australias wetland wealth. Habitat Australia

25, 1321.

G. Herath / Journal of Environmental Management 70 (2004) 263273 273