Incontinence-associated Dermatitis · J WOCN Volume 34/Number 1 Gray et al 47 TABLE 1. Instruments...

Transcript of Incontinence-associated Dermatitis · J WOCN Volume 34/Number 1 Gray et al 47 TABLE 1. Instruments...

Copyright © 2007 by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society J WOCN ■ January/February 2007 45

WOUND CARE

Incontinence-associated DermatitisA Consensus

Mikel Gray � Donna Z. Bliss � Dorothy B. Doughty � JoAnn Ermer-SeltunKaren L. Kennedy-Evans � Mary H. Palmer

Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) is an inflammation ofthe skin that occurs when urine or stool comes into contact withperineal or perigenital skin. Little research has focused on IAD,resulting in significant gaps in our understanding of its epidemi-ology, natural history, etiology, and pathophysiology. A grow-ing number of studies have examined clinical and economicoutcomes associated with prevention strategies, but less researchexists concerning the efficacy of various treatments. In the clini-cal and research settings, IAD is often combined with skin dam-age caused by pressure and shear or related factors, sometimesleading to confusion among clinicians concerning its etiologyand diagnosis. This article reviews existing literature related toIAD, outlines strategies for assessing, preventing, and treatingIAD, and provides suggestions for additional research needed toenhance our understanding and management of this commonbut under-reported and understudied skin disorder.

Even though incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) iswidely recognized as a frequent complication of urinary

and fecal incontinence, surprisingly little is known about itsepidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, or manage-ment. To focus greater attention on this problem and to de-fine the existing research and the gaps in clinical evidence,a panel of experts met in Chicago in July 2005. This review,authored by all the panel members, summarizes currentknowledge concerning incontinence-associated skin prob-lems in adults and points out some of the many questionsand issues that require further investigation.

■ Methods

MEDLINE and CINAHL databases were searched using the following key terms: diaper rash, moisture macerationinjury, perineal dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, contact der-matitis, intertrigo, and heat rash. Articles cited were limitedto any published reference that specifically focused on der-matitis associated with fecal and/or urinary incontinence.Thirty-six review, theory-based, and research articles wereidentified and all were included in our review.

■ Definition

A variety of terms have been used to describe incontinence-associated skin problems, but a search of the MEDLINEand CINAHL databases reveals no predominant name forthis disorder. When applied to infants, diaper rash is theprincipal term, and diaper rash is listed as an establishedkeyword in both MEDLINE and CINAHL databases with414 and 119 references published between January 1966and February 2006, respectively. However, this term is notpreferred when describing skin problems in adults for a va-riety of reasons including (1) differences in barrier functionof the skin in adults vs neonates or infants, (2) differencesin products used to contain urine or fecal materials, and(3) the pejorative connotations of the word diaper whenapplied to adults with urinary or fecal incontinence.

Therefore, a number of alternative terms were identifiedthat have been applied to adults, including moisture mac-eration injury, perineal dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, con-tact dermatitis, intertrigo, or heat rash. However, a searchof MEDLINE and CINAHL databases reveals that no singleterm predominates and none adequately describes skinproblems associated with urinary and fecal incontinence.

J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2007;34(1):45-54.Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

� Mikel Gray, PhD, CUNP, CCCN, FAAN, Professor and NursePractitioner, Department of Urology, University of Virginia,Charlottesville.� Donna Z. Bliss, PhD, RN, CCRN, Professor, University ofMinnesota, School of Nursing, Minneapolis.� Dorothy B. Doughty, MN, RN, CWOCN, FAAN, Director of theWound, Ostomy Continence Nursing Education Center, EmoryUniversity, Atlanta, Ga.� JoAnn Ermer-Seltun, RN, MS, ARNP, CWOCN, Mercy MedicalCenter North Iowa, Women’s Health Center—Continence Clinic,Forest Park Building, Mason City, Iowa.� Karen L. Kennedy-Evans, RN, CS, FNP, K. L. Kennedy Inc., Tucson, Ariz.� Mary H. Palmer, PhD, RN, FAAN, Helen W. & Thomas L. UmphletDistinguished Professor in Aging, University of North Carolina atChapel Hill School of Nursing, Chapel Hill, NC.Corresponding author: Mikel Gray, PhD, CUNP, CCCN, FAAN,Department of Urology, University of Virginia, PO Box 800422,Charlottesville, VA 22908 (e-mail: [email protected]).

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 45

46 Gray et al J WOCN ■ January/February 2007

For example, a search using the term perineal dermatitisrevealed only 19 articles published between January 1966and February 2006 in MEDLINE and 14 published duringa similar period in CINAHL. The terms heat rash and mois-ture maceration injury were associated with even fewer ar-ticles, and most of them did not mention incontinence asa causative factor. Irritant dermatitis, contact dermatitis,and intertrigo are established key words with multiple as-sociated articles (more than 10,000 combined), but theyare not specific to skin problems associated with urinary orfecal incontinence.

Among the existing terms, perineal dermatitis pro-duced the highest number of articles specifically associ-ated with incontinence-associated skin problems (19articles listed in the MEDLINE database and 14 in CINAHLbetween 1966 and 2006). However, the perineum is de-fined as the area of skin between the vulva and anus inwomen and the scrotum and anus in men,1 an area muchsmaller than that affected by incontinence-related skinproblems. Therefore, we elected to describe this conditionas Incontinence-associated Dermatitis (IAD). This term waschosen because it adequately describes the response of theskin to chronic exposure to urine or fecal materials (inflam-mation and erythema with or without erosion or denuda-tion), specifically identifies the source of the irritant (urineor fecal incontinence), and acknowledges that a larger areaof the skin than the perineum is commonly affected.

■ Clinical Manifestations and Classification

Researchers and clinicians consistently describe IAD ascharacterized by inflammation of the surface of the skinwith redness, edema, and in some cases bullae (vesicles)containing clear exudate.2-8 Erosion or denudation of super-ficial layers also has been described and is generally asso-ciated with more advanced or severe cases. Nevertheless,several researchers and clinicians point out that IADshould be distinguished from wounds caused by differingetiologies, such as full-thickness wounds (caused by pres-sure and shear) or linear lesions (caused by a skin tear).4,5,9

Kennedy and Lutz3 noted that areas of redness may bepatchy or consolidated, and Gray and colleagues6 observedthat IAD associated with urinary incontinence tends tooccur in the folds of the labia majora in women or the scro-tum in men, whereas IAD associated with fecal inconti-nence tends to originate in the perianal area. Candidiasis,with its characteristic maculopapular rash and satellite le-sions, is identified as a common complication of IAD.3,6

Other potential complications, such as erythrasma, a bac-terial infection of the skin caused by Corynebacterium,have also been observed, but no research was found iden-tifying how often these conditions occur among patientswith IAD.

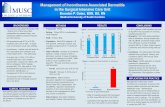

Three instruments have been developed that are specif-ically designed to evaluate IAD2,3,7 (Table 1). The PerinealAssessment Tool2 evaluates IAD risk based on (1) the typeof irritant, (2) the duration of contact, (3) the condition of

the perineal skin, and (4) the total number of contributingfactors. The Perineal Dermatitis Grading Scale is an ex-pansion of the Perineal Assessment Tool7 that incorporateselements of the conceptual framework proposed by Brownand Sears.8 It is designed to assess the scope and severity ofIAD and measure changes in these factors as the result ofnursing interventions. Kennedy and Lutz3 developed theIAD Skin Condition Assessment Tool that generates a cu-mulative severity score based on area of skin affected, degreeof redness, and depth of erosion.

Despite the presence of these tools specifically de-signed for the assessment of IAD, the most common in-strument used for moisture-related skin damage in theperineum and groin is the staging system promulgatedby the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP).10

Under this system, a stage 1 wound is defined as a changein skin temperature, tissue consistency, or sensation in thepresence of intact skin and a stage 2 wound indicates par-tial thickness skin loss involving epidermis, dermis, orboth. Whether stage 1 and stage 2 wounds are intended todescribe lesions caused by irritants acting at the surface ofthe skin (top-down injury) or pressure acting on deep tis-sues (bottom-up damage) remains unclear. Higher stages(3 and 4) indicate full-thickness wounds, but they areclearly associated with deep tissue injury and subsequentpressure ulceration.

Since the NPUAP staging system was designed to mea-sure the extent of tissue destruction caused by pressure in-jury, we do not recommend its use for the classification ofIAD. The Perineal Assessment Tool has undergone contentvalidation by WOC nurses and may be used to assess IADrisk.2 Inter-rater reliability was reported as 87%. The PerinealDermatitis Grading Scale was described by Brown in 1993,7

but a review of MEDLINE and CINAHL databases did notreveal any reports of validity or reliability testing, or sub-sequent studies using the tool. Because none of these in-struments has been used extensively in research or clinicalsettings, we recommend that they be combined with reg-ular, descriptive assessments of skin folds within the per-ineum, the lower abdomen, between the buttocks andadjacent skin folds of the inner thighs, scrotum, or labiamajora when assessing an individual patient.

■ Epidemiology

A limited number of studies were identified that reportprevalence or incidence of IAD. Reported prevalence ratesvary from 5.6% to 50%.11-18 Incidence rates, usually reportedover a period of 4 weeks, vary from 3.4% to 25%.13,15 Moststudies were conducted in long-term care settings andwere based on small samples in single institutions, al-though two studies15,16 were drawn from multiple nursinghomes in the United States representing a sample size of1918 residents, and a single acute care based study18 wasbased on a sample of 976 subjects. Although data fromthese studies provide some estimate of the prevalence and

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 46

J WOCN ■ Volume 34/Number 1 Gray et al 47

TABLE 1.

Instruments for Evaluating Incontinence-associated Dermatitis (IAD)

Reference (Instrument Name) Factors Scoring

Nix2 (Perineal Assessment Tool)

Brown,7 Brown and Sears8 (Perirectal Skin Assessment Tool)

Kennedy and Lutz3

(IAD Skin Condition Assessment Tool)

I. Type and intensity of irritant0. Formed stool and/or urine1. Soft stool with or without urine2. Liquid stool with or without urine

II. Duration of irritant0. Linen/pad change at least every 2 hours or less1. Linen/pad change at least every 4 hours or less2. Linen/pad change at least every 8 hours or less

III. Perineal skin condition0. Clear and intact1. Erythema/dermatitis with or without candidiasis2. Denuded/eroded skin with or without dermatitis

IV. Contributing factors (low albumin, antibiotics, tube feeding,Clostridium difficile)0. 0 to 1 contributing factor1. 2 contributing factors2. 3 or more contributing factors

I. Skin color0. No erythema1. Mild erythema2. Moderate erythema3. Severe erythema

II. Skin integrity0. Intact1. Slight swelling with raised areas2. Swollen raised areas3. Bullae or vesicles4. Open or macerated areas5. Crusted or scaling areas

III. SizeMeasured in centimeters, reporting both length and width, first for theright side then for the left side

IV. Patient symptoms0. None1. Tingling2. Itching3. Burning4. Pain

I. Area of skin breakdown0. None1. Small area (<20 cm2)2. Moderate area (20-50 cm2)3. Large area (>50 cm2)

II. Skin redness0. No redness1. Mild redness (blotchy and nonuniform in appearance)2. Moderate redness (severe in spots but not uniform in appearance)3. Severe redness (uniformly severe in appearance)

III. Erosion0. None1. Mild erosion involving epidermis only2. Moderate erosion involving epidermis and dermis with no or little

exudate3. Severe erosion of epidermis with moderate involvement of dermis

(low volume or no exudate)4. Extreme erosion of epidermis and dermis with moderate volume

(persistent exudate)

Cumulative score calculated, higherscore indicates higher risk for IAD

Descriptive instrument, no cumulativescore is calculated, clinicians areencouraged to include additionaldescriptors to describe IAD whenindicated

Cumulative score calculated withhigher numbers indicating moresevere IAD

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 47

48 Gray et al J WOCN ■ January/February 2007

incidence of IAD in the acute and long-term care settings,further research is urgently needed to determine its occur-rence in critical care units, in acute care, and in the com-munity and homecare settings.

Only one study was identified that reported the preva-lence of associated fungal infections. Junkin and associates18

found that 18% of a group of 198 patients with urinary,fecal, or double incontinence had evidence of fungal infec-tion of the skin in the perineum, perianal, or groin area.Diagnosis was based on visual inspection, and no reliabilitytesting of diagnosis was reported.

Little research exists focusing on the natural history ofIAD, including the time to onset, spontaneous remission,and recurrence rates. Additional research is needed to elu-cidate these factors because this knowledge is essential inorder to identify risk factors.

■ Pathophysiology

Given the paucity of data on the epidemiology of IAD, itis not surprising that relatively little is known about its eti-ology and pathophysiology. Nevertheless, a number offactors have been identified that are likely to interact, pro-ducing the characteristic skin damage of IAD (Figure 1).Brown19 designed a conceptual framework for factorscontributing to IAD based on an integrative review of 16 articles. Brown19 hypothesized a multifactorial etiologyand identified 3 principal areas contributing to IAD: (1) tis-sue tolerance, (2) perineal environment, and (3) toiletingability. Critical elements determining tissue tolerance in-clude the patient’s age, health status, nutritional status,oxygenation, perfusion, and core body temperature. Theperineal environment is affected by the character of incon-tinence (urinary, fecal or double urinary and fecal inconti-nence), the volume and frequency of incontinence,mechanical chafing, inducing agents such as irritants or al-lergens, and factors that compromise the skin’s barrier func-tion such as hydration, pH, fecal enzymes, and fungal orbacterial pathogens. Toileting ability is conceptualized asmobility, sensory perception, and cognitive awareness.Brown19 subsequently completed a validation study of thisframework with a group of 166 patients being treated in anacute care facility. Among the factors identified in the con-ceptual framework, fecal incontinence, frequency of incon-tinence, poor skin condition, pain, poor skin oxygenation,fever, and compromised mobility were statistically signif-icantly correlated with IAD.

Bliss and associates17 extended the application ofBrown’s model19 to elderly nursing home residents. Theyoperationally defined the model’s variables using items onthe Minimum Data Set (MDS), a standardized computer-ized instrument used for the comprehensive assessment ofthe cognitive, physical, and social function, and clinicalstatus of nursing home residents. Unlike Brown,19 Blissand associates17 were able to analyze cognitive status andadd restraint use and double incontinence to their analy-

sis given the scope of the MDS and their large data set.Perineal dermatitis was defined using clinician’s orders inthe medical record. The final data set contained 59,558MDS records and 2,883,049 practitioner orders for residentsin 555 nursing homes in 31 states. Data from 2 subsam-ples, each with the records of 10,215 older nursing homeresidents, were analyzed using logistic regression to iden-tify the significant factors associated with perineal der-matitis.

Of note among the findings of Bliss and associates17

was that having fecal incontinence only held the strongestrelationship to perineal dermatitis; there was no signifi-cant association between perineal dermatitis and havingurinary incontinence only. Other significant factors forperineal dermatitis in the perineal environment categorywere having double incontinence and more MDS items as-sociated with mechanical chafing. Impairments of tissuetolerance category (ie, more health problems, presence offever, requiring nutrition support, and having more prob-lems of diminished perfusion or oxygenation) and alteredtoileting ability from daily use of restraints were other sig-nificant factors.

Other researchers and clinicians have focused on top-ical factors influencing the skin’s barrier function.6,13,20 Ina review of the pathophysiology of contact dermatitis thatwas not specific to IAD, Ghadially21 defined the skin’s barrier function as a 2-component system comprising amultilayered plate of hydrophobic lipids (sometimes described as mortar) filling the intercellular spaces be-tween lipid-depleted keratinocytes. These lipids are com-posed of ceramides, free fatty acids, and cholesterol, aswell as hydrolytic enzymes that optimize the efficiency ofthe skin barrier. Disruption of this barrier leads to releaseof cytokines and localized inflammation characterized byan increased production of cholesterol, ceramides, andfatty acids, and inhibition in enzyme function reducingthe normal cycle of lipid breakdown until the skin’s bar-rier function is fully restored. In addition, cytokine releaseand inflammation provoke DNA synthesis and epidermalhyperplasia, in an attempt to restore the “bricks” of theskin’s barrier, the keratinocytes of the stratum corneum.Given an isolated injury to the skin’s barrier function suchas tape stripping, the body is able to complete repairs withina period of a few days to several weeks. However, when theskin is exposed to an irritant over a prolonged period or isexposed multiple times before it can fully repair itself, a vi-cious cycle is established characterized by incomplete repairand increasing inflammation and damage. Aging skin hasbeen shown to have lower baseline function and recoverytime following an acute insult and is particularly vulnera-ble to damage from long-term exposure to surface irritantssuch as urine or stool.21

The use of absorptive or occlusive containment deviceshas also been identified as a contributing factor. In onestudy of incontinent patients in acute care facilities, 93%of a group of 198 patients with urinary and/or fecal in-

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 48

J WOCN ■ Volume 34/Number 1 Gray et al 49

continence and IAD were managed with absorptive prod-ucts, compared to 7% who were not.18 Prolonged occlu-sion of the skin under an absorptive incontinence productfor 5 days has been shown to cause an increased sweat pro-duction and compromised barrier function, resulting inelevated transepidermal water loss, CO2 emission, andpH.22-23 In addition, the microflora of the skin undergoes amarked increase in coagulase-negative staphylococci. Zhaiand Maibach24 demonstrated that application of a conti-nence containment device to normal skin produces hyper-hydration that is proportional to exposure time. Warner

and coworkers25 demonstrated that saline, or water alone,acts as an irritant leading to contact dermatitis in the pres-ence of an occlusive device that does not effectively wickmoisture away from the surface of the skin.

Incontinence-associated dermatitis has also been associ-ated with an alkaline pH of the surface of the skin. Berg andcoworkers26 combined data from 4 clinical trials to deter-mine the influence of moisture and pH on IAD risk in in-fants. Consistent with the results of Aly’s group,23 theyfound that skin covered by a diaper had a higher pH com-pared to skin that was left open to air. Although moisture

FIGURE 1. Reproduced with permission from Sage, copyright 2006.

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 49

50 Gray et al J WOCN ■ January/February 2007

emerged as the principal factor associated with IAD, an al-kaline pH was also associated with an increased likelihoodof developing IAD. Burgoon and colleagues27 hypothesizedthat microflora from fecal incontinence might convert ureafrom urinary leakage to ammonia, but Leyden and associ-ates28 did not support this assertion. However, Berg andcoworkers26 did demonstrate that an alkaline pH in personswith double fecal and urinary incontinence activates fecalenzymes, increasing the likelihood of damage when exposedto intact skin.

Urinary leakage is postulated to contribute to the riskof IAD by hyperhydrating exposed skin, by increasing itspH, and possibly by interacting with stool to activate fecalenzymes.28 In addition, urine may diminish the tissue tol-erance of the perineal and perigenital skin. In a study ofhealthy adult volunteers, Mayrovitz and Sims29 demon-strated that skin wetted with synthetic urine exhibited asignificant decrease in skin hardness, temperature, andblood flow during pressure load when compared to drysites. Fader and associates30 demonstrated that absorbentproducts actually increased tissue interface pressures whensoaked, even when used in conjunction with pressure-reducing or relieving support surfaces.

When multiple factors are entered into a multivariatestatistical analysis, fecal incontinence tends to emerge aseven more strongly associated with IAD than use of an ab-sorptive containment device or urinary incontinencealone.5,8 Several elements of stool may contribute to thisassociation, including fecal enzymes, intestinal flora, andmoisture if the stool is liquid in nature. Nix2 differentiatesliquid stool from solid stool in her instrument, based onclinical experience and the expert opinion of others thatliquid stool tends to be richer in digestive enzymes, which,when combined with its elevated water content, is partic-ularly damaging to the skin.

■ Prevention

Literature review reveals 5 studies that evaluated the efficacyof a routine skin care protocol for the prevention or treat-ment of IAD.13,16,31-33 Although the protocols for skin carevaried in product choice or number of steps, each includedcleansing with soap and water or a perineal skin cleanser,with or without application of a moisturizer and/or a skinprotectant. Soap is made from a mixture of alkalis and fattyacids. Its ability to cleanse the skin requires decompositionin water releasing free alkali and insoluble acid salts that re-move dirt and irritating substances from the skin.34 Perinealskin cleansers combine detergents and surfactant ingredi-ents to loosen and remove dirt or irritants; many also con-tain emollients, moisturizers, or humectants to restore orpreserve optimal barrier function. Because they contain al-kalis, the pH of soap tends to be higher than that of nor-mal skin. In contrast, many perineal skin cleansers are “pHbalanced” in order to ensure that their pH is closer to thatof healthy skin (5.0-5.9).35 A skin protectant is a product

that isolates exposed skin from harmful or annoying sub-stances. In the context of a skin care regimen for IAD, skinprotectants are capable of isolating the skin from excessivemoisture, urine, or stool.

Lyder and colleagues13 enrolled 15 patients who werefree of IAD at baseline and compared 2 skin care regimensover a 10-week period. During a 4-week period, subjectswere managed by an unstructured perineal skin care regi-men. During a subsequent 4-week period, subjects weremanaged by a structured regimen, described as applicationof a cleanser, moisturizer, and moisture repellant to theperineal skin after each incontinent episode (specific prod-ucts used in the structured program were not specified).The incidence of IAD over a 4-week period was 23%; it wasidentical in the two groups.

Byers’ group31 and Lewis-Byers and Thayer33 comparedsoap and water to no-rinse perineal cleansing products in10 elderly women without IAD over a period of 3 weeks.They compared 4 skin care regimens: (1) cleansing withsoap and water alone, (2) cleansing with a no-rinse skincleanser alone, (3) cleansing with soap and water followedby application of a skin protectant, and (4) cleansing witha no-rinse skin cleanser plus a moisturizer. Erythema,transepidermal water loss, and altered skin pH were mostsevere among women managed by soap and water aloneand least severe for women managed by the regimen thatcombined the lower pH cleanser with a moisturizer.Although these indirect outcomes favored use of a no-rinse skin cleanser with a pH similar to that of healthyskin, the study was not adequately powered, and data col-lection did not occur over a sufficient period of time tomeasure whether these outcomes reflected differences inthe occurrence of IAD in the various treatment groups.

Lewis-Byers and Thayer33 randomly assigned 32 nursinghome residents to 1 of the 2 skin care regimens: (1) cleans-ing with soap and water after each incontinence episode, followed by application of a moisturizing lotion or (2)cleansing with a no-rinse skin cleanser after each episode,followed by application of a barrier cream after the first in-continence episode of each shift. After 3 weeks of data col-lection, no statistically significant difference in maintenanceof skin integrity between the groups was detected (69% vs72%). However, use of the no-rinse cleanser did significantlyreduce the amount of staff time required to perform perinealskin care (mean time reduction = 79 minutes per day).

Bliss and coworkers16 compared the efficacy of 4 skincare regimens to prevent IAD in nursing home residents in a multisite, nationwide study. The skin care regimens included (1) an acrylate polymer-based barrier film applied3 times per week, (2) a 43% petrolatum ointment appliedafter each incontinent episode, (3) a combination of 12%zinc oxide-1% dimethicone cream applied after each in-continence episode, and (4) a 98% petrolatum-containingointment that was applied after each incontinence episode.Of the 1918 nursing home residents who were screened forenrollment, 51% (n = 981) had urinary and/or fecal incon-

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 50

J WOCN ■ Volume 34/Number 1 Gray et al 51

tinence and were free from perineal skin damage qualify-ing for a 6-week prospective surveillance of the occurrenceof IAD. There was no significant difference in the develop-ment of new cases of IAD in any of the regimens. The over-all incidence of IAD among the nursing home residents was3.4% and the incidence of any perineal skin damage (eg, in-cluding pressure ulcers) was 4.6%. The results suggest thatuse of a defined skin care regimen and quality skin careproducts is associated with a low incidence of IAD in a high-risk population.

One study was identified that focused on the efficacyof a thick, disposable washcloth that combined a no-rinsecleanser, a moisturizer, and a skin protectant (3% dimethi-cone).32 During a 12-week preintervention observationperiod, 5 of 34 subjects with fecal or urinary incontinence(15%) developed what were described as stage 1 or stage 2wounds. No subject developed a stage 1 or stage 2 woundduring the 12-week intervention phase, a statistically sig-nificant difference.

In addition to these studies, 3 research reports wereidentified that examined the effects of “structured perinealskin care regimens” in patients with a variety of skin prob-lems including IAD, skin tears, and/or pressure ulcers.5,14,32

They are not included in considerations of the efficacy ofa structured skin care regimen for the prevention of IADbecause they enrolled subjects who were continent atbaseline, and outcomes were based on any form of skinbreakdown rather than the development of IAD specifi-cally. Nevertheless, each of these studies did find that in-stitution of a structured skin care regimen over a 12-weekperiod resulted in a statistically significant reduction inthe incidence of perineal and/or sacral skin breakdown.

Based on these findings and clinical experience, reviewarticles tend to recommend a routine perineal skin careprogram that includes cleansing with a product whose pHrange approximates that of normal skin (Table 2). Careproviders were counseled that the skin should be cleansedgently, being careful to avoid rigorous scrubbing or fric-tion in order to minimize the risk of further compromis-ing the skin’s barrier function.4,6,35 Moisturization of theskin was also recommended for all patients. A variety ofover-the-counter products containing humectants or emol-lients may be applied in a second step, or a moisturizermay be incorporated into a specially designed cleanser orcleansing system. Finally, routine use of a skin protectantis recommended for patients considered at risk of IAD,including those experiencing high volume or frequentincontinence or double urinary and fecal incontinence.Multiple products that act as skin protectants are advo-cated; most of them are applied as an ointment containingpetrolatum, dimethicone, or zinc oxide. However, clini-cians also advocate application of products that incorpo-rate a skin protectant into a 1-step cleansing solution orsystem, thus reducing the time required to adequatelycleanse and protect the perineal and perigenital skin in per-sons with urinary or fecal incontinence.

■ Treatment

An extensive literature review revealed only one studythat specifically evaluated a treatment protocol for exist-ing IAD. Warshaw and colleagues36 examined the effec-tiveness of a cleanser containing a skin protectant in anopen label uncontrolled study of 19 elderly patients withIAD characterized by erythema of the skin and associatedpain but without denudation. Following 7 days of treat-ment in which subjects averaged 2.3 care episodes perday, both the severity of erythema and pain were signifi-cantly reduced.

Because of the lack of research focusing on the manage-ment of existing IAD in adults, recommendations for treat-ment must be based on clinical experience and expertopinion (Table 2). Recommendations for treatment of mild-to-moderate IAD (characterized by erythema and tender-ness of intact skin) consist of a structured skin care regimensimilar to those recommended for prevention with the ad-dition of a skin protectant.4,6,35 Structured skin care shouldbe provided following each major incontinence episode,particularly if fecal matter is present. This regimen shouldinclude a cleanser that is no-rinse and “pH balanced” (for-mulated with a pH range similar to that of healthy skin),and a skin protectant should be applied at least daily. Themoisture protectant should be applied more frequently inpatients with high-volume or frequent episodes of inconti-nence.3 Combination products are usually encouraged,because they reduce several steps into a single interven-tion, maximizing time efficiency and encouraging ad-herence to a structured skin care regimen. Combinationproducts include moisturizing cleansers, moisturizer-skinprotectant creams, and disposable washcloths that incor-porate cleansers, moisturizers, and skin protectants into asingle product. Staff should be educated about principles ofperineal skin care, including the need to avoid vigorousscrubbing that may damage already compromised skin.

Complementary interventions include active measuresto minimize urinary or fecal incontinence including a sched-uled toileting program when feasible, use of a polymer-basedabsorptive product to wick urine or liquid stool away fromthe skin, or consideration of a containment device such asa condom catheter or anal pouch that reduces the area ofskin exposed to stool or urine. Maximizing hydration andensuring adequate nutritional support to meet the needsfor wound healing are also recommended.

Recommendations for treatment of patients with moresevere IAD associated with denudation of the skin varysomewhat. Limited clinical evidence pertaining to the pre-vention of IAD and multifactorial perineal skin breakdownprevention programs suggest that a structured skin care pro-gram combined with regular application of a skin protec-tant product may provide adequate protection to promotehealing in some patients,5,14,32 particularly when combinedwith complementary interventions designed to reduce thefrequency of incontinent episodes. Other interventions

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 51

52 Gray et al J WOCN ■ January/February 2007

TABLE 2.

Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment of Incontinence-associated Dermatitis (IAD)

Condition of Skin Treatment Goals Interventions

Intact skin in person with urinary or fecal incontinence

Mild-to-moderate IAD (skin remains intact but erythema present, with or without candidiasis)

Prevent IADMinimize contact with irritants

(urine, stool, and excessivemoisture)

Maintain skin protectionReduce barriers to appropriate care

Minimize contact with irritants(urine, stool, and excessivemoisture)

Maintain skin protection

Eradicate cutaneous candidiasis

Begin a structured skin care regimen(1) Cleanse perineal skin daily and after each major incontinence

episode using a no-rinse cleanser(2) Avoid scrubbing the skin; use a soft or disposable washcloth(3) Apply an appropriate moisturizer (often a cream product

containing humectant and emollient)(4) Apply a skin protectant to minimize contact between urine

and/or stool [ointment containing petrolatum, zinc oxide,dimethicone, or combination of these products, or apply acopolymer film product (skin sealant) in patients judged to be athigh risk for developing IAD (high-volume/high-frequencyurinary or fecal incontinence, double fecal and urinaryincontinence, and fecal incontinence with liquid stool)]

(5) Combine steps using a product containing a cleanser plus amoisturizer with or without a skin protectant

(6) Educate caregivers to apply structured skin regimen and routinelyassess for IAD

(7) Begin aggressive treatment program for underlying incontinence

(1) Combine a structured skin care program with active treatmentof IAD

(2) Routinely cleanse and moisturize the skin using the steps notedabove

(3) Routinely apply a skin protectant, options include:(a) an ointment containing petrolatum, zinc oxide,

dimethicone, or combination of these products(b) a copolymer film product (skin sealant)(c) skin protectant ointment with active ingredients designed to

promote wound healing [Balsam-Peru, castor oil, andtrypsin (BCT) ointment or BCT gel]

(4) Treat cutaneous candidiasis when present(5) Apply moisturizer or moisture-barrier combination product with

antifungal agent (azole or allylamine)(6) Educate caregivers to apply structured skin regimen and

routinely assess for resolution or progression of IAD(7) Evaluate or begin management program for underlying

incontinence

include application of a skin paste made of zinc oxide andan absorptive powder. Evidence also supports the use of aprescriptive ointment containing Balsam-Peru, castor oil,and trypsin (BCT ointment). BCT ointment has been shownto promote healing of partial thickness wounds in both lab-oratory and clinical settings.37-39 This formulation is hy-pothesized to be beneficial for the treatment of IAD becauseit contains ingredients that promote wound healing in anointment that protects the skin against further moisture-related skin damage.

■ Economic Considerations

Although the cost of pressure ulcer treatment has been estimated in multiple studies,32 comparatively little isknown about the economic impact of IAD. It is suspectedthat pressure ulcer treatment cost data may include someof the cost associated with misdiagnosed skin injuries that

are not pressure related but instead are skin injuries suchas dermatitis due to incontinence, fungal infections, skintears, and injuries caused from friction and shear. In orderto accurately capture the cost of prevention and treat-ment of IAD, the staff assigned to collect data in thehealthcare facility must have accurate skin care assess-ment skills to correctly differentiate pressure ulcers fromother skin injuries in order to appropriately treat and de-termine cost.40

Three studies were identified that incorporated the costof preventing or treating IAD with wounds caused by otherfactors.14,32,37 Bale and coworkers14 measured costs associ-ated with a reduction in staff time required to complete anintervention when using a no-rinse skin cleanser as com-pared to soap and water. Clever and associates32 calculateda reduced cost when a combination product was comparedto a multiple-step skin care regimen in terms of staff timeand direct product costs. Similarly, Narayanan and associ-

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 52

J WOCN ■ Volume 34/Number 1 Gray et al 53

ates37 found reduced staff time when BCT ointment wascompared to a variety of other treatment interventions forpartial thickness skin lesions in patients with urinary orfecal incontinence. These studies suggest that use of a no-rinse skin cleanser, or a skin cleanser that incorporates amoisturizer and/or skin protectant, has economic advan-tages compared to cleansing with soap and water.

Other studies examined the cost of individual productsused to treat or prevent IAD. Nix and Seltun35 studied di-rect costs of skin protectants and found an average of only$0.10 per day spent on institutionalized incontinent pa-tients, whereas the anticipated cost (based on average saleprices of barrier protectants) should be $0.23 per applica-tion. Rather than suggesting positive cost savings, the re-sults of this study suggest that prevention measures werenot routinely administered, thus increasing the risk of de-veloping IAD and the costs associated with its treatment.

In their nationwide study of IAD prevention in nurs-ing homes, Bliss and coworkers16 conducted an economicanalysis of 4 skin care regimens. As described previously,the regimens included (1) an acrylate polymer-based bar-rier film applied 3 times per week, (2) a 43% petrolatumointment applied after each incontinent episode, (3) acombination of 12% zinc oxide-1% dimethicone creamapplied after each incontinence episode, and (4) a 98%petrolatum-containing ointment that was applied aftereach incontinence episode. When total costs of the regi-mens (labor, products, and supplies) were compared, theaverage cost per treatment ranged from $0.89 per episodeof incontinence for the regimen in which the acrylatepolymer-based barrier film was applied 3 times per week to$1.74 per episode for the regimen in which petroleum(43%) ointment was applied after each episode of inconti-nence. The results suggest that the properties of the skincare products and their recommended administrationneed to be considered in cost analyses.

Two studies reported total skin care supply costs for in-continence care regimens in 3 separate long-term care fa-cilities. Lyder and associates41 reported an average cost perday of $5.19 when utilizing a no-rinse cleanser, skin mois-turizer, and barrier ointment on incontinent residentsafter each episode. Clever and colleagues32 studied the im-pact of changing the skin care protocol in a long-term carefacility to an all-in-one-step product that incorporates athick disposable washcloth, a cleanser, a moisturizer, anda skin barrier. Estimated average cost per day per inconti-nent resident dropped from $1.56 to $1.67 utilizing the old standard of care (disposable wipes and a 1.5% di-methicone barrier cream) to $1.07 to $1.15 per day withthe new regimen.

■ Summary

Incontinence-associated dermatitis is a common problemaffecting as many as half of the patients with urinary orfecal incontinence who are managed with absorptive prod-

ucts. However, a review of the literature reveals sparse ev-idence concerning its epidemiology, etiology, and patho-physiology. A small but growing body of evidence existsthat various preventive skin regimens are important, butsignificant additional research is needed in order to iden-tify and evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of variousinterventions for IAD.

■ References1. Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. 27th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott,

Williams and Wilkins; 2000.2. Nix DH. Validity and reliability of the Perineal Assessment

Tool. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2002;48(2):43-46, 48-49.3. Kennedy KL, Lutz L. Comparison of the efficacy and cost-

effectiveness of three skin protectants in the management of incontinent dermatitis. In: Proceedings of the EuropeanConference on Advances in Wound Management. Amsterdam;October 4, 1996.

4. Gray M. Preventing and managing perineal dermatitis: ashared goal for wound and continence care. J Wound OstomyContinence Nurs. 2004;31(suppl 1):S2-S9.

5. Hunter S, Anderson J, Hanson D, Thompson P, Langemo D,Klug MG. Clinical trial of a prevention and treatment protocolfor skin breakdown in two nursing homes. J Wound OstomyContinence Nurs. 2003;30(5):250-258.

6. Gray M, Ratliff C, Donovan A. Perineal skin care for the in-continent patient. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2002;15:170-179.

7. Brown DS. Perineal dermatitis: can we measure it? OstomyWound Manag. 1993;39(7):28-30, 32.

8. Brown DS, Sears M. Perineal dermatitis: a conceptual frame-work. Ostomy Wound Manag. 1993;39(7):20-22, 24-25.

9. Bryant RA, Rolstad BS. Examining threats to skin integrity.Ostomy Wound Manag. 2001;47(6):18-27.

10. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Staging Report. Avail-able at: http://www.npuap.org/archive/positn6.htm. AccessedSeptember 2005.

11. Keller PA, Sinkovic SP, Miles SJ. Skin dryness: a major factor inreducing incontinence dermatitis. Ostomy Wound Manag. 1990;30:60-64.

12. Sowell VA, Schnelle JF, Hu TW, Traughber B. A cost compari-son of five methods of managing urinary incontinence. QRBQual Rev Bull. 1987;13(12):411-414.

13. Lyder CH, Clemes-Lowrance C, Davis A, Sullivan L, Zucker A.Structured skin care regimen to prevent perineal dermatitis inthe elderly. J ET Nurs. 1992;19(1):12-16.

14. Bale S, Tebble N, Jones V, Price P. The benefits of implementinga new skin care protocol in nursing homes. J Tissue Viability.2004;14(2):44-50.

15. Bliss DZ, Savik MS, Zehrer C, Thayer D, Smith G. Incontinencedermatitis in nursing home residents. In: 18th Symposium onAdvanced Wound Care. San Diego, CA; April 2005.

16. Bliss DZ, Zehrer C, Ding L, Hedblom E. An economic evalua-tion of skin damage prevention regimens among nursinghome residents with incontinence: labor costs. J Wound OstomyContinence Nurs. 2005;32(suppl 3):51.

17. Bliss DZ, Savik K, Harms S, Fan Q, Wyman JF. Prevalence andcorrelates of perineal dermatitis in nursing home residents.Nurs Res. 2006;55(4):243-251.

18. Junkin J, Moore-Lisi L, Selekof J. What we don’t know can hurtus, pilot prevalence survey of incontinence and related per-ineal skin injury in acute care [abstract]. 2005. WOCN NationalConference, Las Vegas NV, June 2005.

19. Brown DS. Perineal dermatitis risk factors: clinical validation ofa conceptual framework. Ostomy Wound Manag. 1995;41(10):46-48, 50, 52-53.

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 53

54 Gray et al J WOCN ■ January/February 2007

20. Faria DT, Shywader T, Krull EA. Perineal skin injury: extrinsicenvironmental risk factors. Ostomy Wound Manag. 1996;42(7):28-30, 32-34, 36-37.

21. Ghadially R. Aging and the epidermal permeability barrier: implications for contact dermatitis. Am J Contact Dermat.1998;9(3):162-169.

22. Ghadially R, Brown BE, Sequeira-Martin SM, Feingold KR,Elias PM. The aged epidermal permeability barrier. Structural,functional, and lipid biochemical abnormalities in humansand a senescent murine model. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(5):2281-2290.

23. Aly R, Shirley C, Cunico B, Maibach HI. Effect of prolonged oc-clusion on the microbial flora, pH, carbon dioxide and trans-epidermal water loss on human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1978;71(6):378-381.

24. Zhai H, Maibach HI. Occlusion vs. skin barrier function. SkinRes Technol. 2002;8:1-6.

25. Warner MR, Taylor JS, Leow YH. Agents causing contact ur-ticaria. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:623-635.

26. Berg RW, Milligan MC, Sarbaugh FC. Association of skin wet-ness and pH with diaper dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11(1):18-20.

27. Burgoon CF, Urbach F, Grover WD. Diaper dermatitis. PediatrClin North Am. 1961;18:835-856.

28. Leyden JJ, Katz S, Stewart S, et al. Urinary ammonia and am-monia producing microorganisms in infants with and withoutdiaper dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1997;113:1678-1680.

29. Mayrovitz HN, Sims N. Biophysical effects of water and syn-thetic urine on skin. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14(6):302-308.

30. Fader M, Bain D, Cottenden A. Effect of absorbent inconti-nence pads on pressure management mattresses. J Adv Nurs.2004;48(6):569-574.

31. Byers PH, Ryan PA, Regan MB, Shields A, Carta SG. Effects of incontinence care cleansing regimens on skin integrity. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 1995;22(4):187-192.

32. Clever K, Smith G, Browser C, Mujroe EA. Evaluating the effi-cacy of a uniquely delivered skin protectant and its effect onthe formation of sacral/buttock pressure ulcers. Ostomy WoundManag. 2002;48(12):60-62, 64-67.

33. Lewis-Byers K, Thayer D. An evaluation of two incontinenceskin care protocols in a long-term care setting. Ostomy WoundManag. 2002;48(12):44-51.

34. Nix DH. Factors to consider when selecting skin cleansing prod-ucts. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2000;27(5):260-268.

35. Nix D, Seltun J. A review of perineal skin care protocols andskin barrier product use. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2004;50(12):59-62, 64-67.

36. Warshaw E, Nix D, Kula J, Markon CE. Clinical and cost effec-tiveness of a cleanser protectant lotion for treatment of per-ineal skin breakdown in low-risk patients with incontinence.Ostomy Wound Manag. 2002;48:44-51

37. Narayanan S, Van Vleet J, Strunk B, Ross RN, Gray M. Pressureulcer treatments in long term care facilities. J Wound OstomyContinence Nurs. 2005;32(3):163-170.

38. Gray M, Jones DP. The effect of different formulations of equiv-alent active ingredients on the performance of two topicalwound treatment products. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2004;50(3):34-44.

39. Mars-Irslinger R, Hensby CN, Farley KL. Experimental methodsto demonstrate the efficacy and safety of Xenaderm ointment:a novel formulation for treatment of injured skin due to pres-sure ulceration. Wounds. 2003;15(suppl):2S-8S.

40. Robinson C, Gloeckner M, Bush S, et al Determining the effi-cacy of a pressure ulcer prevention program by collectingprevalence and incidence data: a unit based effort. OstomyWound Manag. 2003;9(5):44-51.

41. Lyder CH, Shannon R, Emplio-Frazier O, McGeHee D, WhiteC. A comprehensive program to prevent pressure ulcer in longterm care: exploring cost and outcomes. Ostomy Wound Manag.2002;48(4):52-62.

10300-08a_WJ3401-Gray.qxd 1/3/07 1:35 PM Page 54