The Life of Jesus (30) Teachings Concerning Judgment The Lord’s Return (1) Matthew 24:36-25:13.

In but not of the World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning ...

Transcript of In but not of the World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning ...

In but not of the World:

The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

By J. Bruce Long

ABSTRACT

Traditionally, the academic study of Buddhism in the West, has focused primarily on the exploration of textual and monastic Buddhism, with significantly less emphasis on the study of the Buddhist view of the life of the laity, and in particular, the world of business and economics.

All of that has begun to change. With the maturation of the field of Buddhist Studies in all its aspects and the expansion of the influence of Buddhism nationally, an interest in the exploration of the more "this-worldly" aspects of Buddhist beliefs and practices is on the rise.

The aim of this paper is to explore those aspects of The Buddha 's teachings that instruct the layman on proper and efficacious ways of establishing a socially-responsible and successful livelihood in this world, by promoting a morally upright and comfortable lifestyle as a householder, serving as a responsible and productive citizen of his community and hopefully, at the end of his lifetime, realizing a good and blissful destiny in the world beyond.

In an attempt to illuminate the Buddha 's approach to the economic life, in general, this paper will include brief discussions of the following topics: ( 1) the dual focus of The Buddha's teachings, (2) two types of desire, (3) the role of ethics in the economic life, (4) .

the ethic of the householder, (5) three distinctive character traits of the monk and the layperson, (6) the centrality of human action in determining the acquisition of success and wealth, and (7) profitable possessions for the advancement of life in this world and in the world beyond.

This paper attempts to provide a comprehensive overview of the attitude toward life in this world and the economic aspect of that life, in particular, revealed in the teachings of Gotama, The Buddha, as recorded in the four primary volumes of the Discourses of the Buddha (Nikayas) . Our objective is to derive a general perspective on the Buddha's view of the moral and profession life of the lay person as a contribution toward the attempt to clarify a rational understanding of Buddhist Economics.

The paper will traverse a broad scholarly terrain that is quite well-known to all students of "early Buddhism." But, it is my intention, here, to cast these familiar materials into a slightly different perspective than they customarily are observed, namely, within the context of the more general topic of Buddhist Ethics and Buddhist Economics.

The main title of this paper, "In but not of the World," is a phrase borrowed from the writings of St. Paul, universally recognized as the first Christian missionary and the creator of the fundamentals of Christian theology and of the Church, itself. But it is an extremely useful phrase within the field of the History

In but not Qf the World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

of Religions, more generally, because of its applicability to all so-called "salvation religions." I refer here specifically to the distinction between two different ways of "being in the world," i.e., the way of the unbeliever vs the believer, the path of purity vs impurity, the way of righteousness vs unrighteousness, etc. The archetypal statement for this need to separate oneself from the world of the unclean, the impure, the false, etc. is St. Paul's call for all believers to" ... come out from among them and be separate, says the Lord and touch nothing un-clean ... " (II Corinthians 6: 17) The words could have just as readily come from the mouth of The Buddha, minus, of course, the reference to

"The Lord." With regard to each of the, so-called, Great Religions, the Founder calls for his devotes to consciously and intentionally remove themselves from all forms of compliance with and participation in the world of the impure, the untrue, the unrighteous, etc., of unenlightened persons and to commit themselves, unreservedly, to the way of purity, truth and righteousness.

The Dual Focus of the Buddha's Teachings

The Buddha and his earliest disciples 'went forth' from the world of the householder (grhasta), with all its encumbering responsibilities and enabling rights, to take up a life of renunciation (sannyasa) or 'wandering homelessness' in order to freely and whole-heartedly pursue the goal of moral and spiritual advancement in this world (samsara) and to achieve the goal of perfect spiritual equanimity or extinction (nirvana) beyond this world. This segment of The Buddha's teachings (dharma) pertains to the "not of this world " in the title of the paper. But this is only one aspect of The Buddha's vision.

While the central emphasis of The Buddha's teachings seems to have been on an ascetical renunciation of all involvement with and commitment to the

"world of sentient beings," this did not form the totality of his message. The central thrust of his message amounted to far more than providing a method of escaping the rap of death and rebirth. It was also His intention to shape, influence and elevate both the internal and external (that is, the moral and spiritual) lives of all human beings within the phenomenal world. 1

As A.K. Warder states the matter: " ... sramanas such as the Buddha hoped from their vantage point outside society to exercise some influence inside it." He goes on to state that, "There is a general underlying assumption that beyond the immediate aim of individual peace of mind, or more probably in essential connection with it, lies the objective of the happiness of the whole of human society and the still higher objective of the happiness of all living beings."2 This aspect of the teachings and training promoted by The Buddha pertains to the "in . . . the world," portion of the paper title.

Thus, a close reading of The Buddha's teachings reveals the fact that he maintained a dual heuristic focus, a position that combined a concern for the quality of life in this world and a concern for the ultimate liberation of all human beings from ignorance, death and rebirth.

This contention is richly evidenced, throughout all of the Pali Suttas. Mention will be made here of some of the primary pieces of evidence. It should

131

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism

be noted, first of all, that, in addition to the institution of the monks (bhikkhu-s) and nuns (bhikkhuni-s), The Buddha also provided a place for the lay men (upasaka-s) and lay women (upasakaa-s), who were all enjoined, without exception, to take refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamrna and the Sangha.

Secondly, The Buddha and his disciples continually interacted with a wide assortment of types of 'worldlings': peasants, merchants, princes, kings, court ministers, soldiers, artisans and a variety of other types of householders. The Buddha himself is often seen dialoguing with them, advising and counseling them, soliciting food and other forms of support from them and, in particular, instructing them on the one true and certain way to achieve moral rectitude and, in the end, spiritual liberation. It is also noteworthy that he and his followers frequented a number of different types of public venues that included cities, villages and pleasure parks, in addition to their chosen mountain and forest retreats.

Another indication of The Buddha's interest in public affairs is a remarkable passage in the Mahaaparinibbana Sutta, regarding, what we now refer to as, each person's "social responsibility." 3 This discourse gives a detailed account of the most important events during The Buddha's final days on earth. One would assume, given the central topic of this discourse, that it would be one of the more spiritually-oriented of all The Buddha's discourses. Interestingly enough, it represents him as presenting to a number of teachers concerning certain topics that are distinctly "the world-oriented" in nature: seven principles of representative government and policies that had enabled the Vajjians to maintain a strong and safe realm, intermixed with teachings on spiritual liberation, final instructions to his disciples and his own final and complete transition into

. . 4 panmrvana.

Many of his public discourses focused on the social obligations and spiritual precepts meant to enhance the life of the laity (upaasakas). Most notable in this regard is the Sigalaka Sutta, or "Advice to the Lay People," the 31st dialogue in the Diigha-Nikaya. In what is, perhaps, The Buddha's most authoritative and comprehensive single declaration of moral principles to undergird and direct the life of non-monastics, he covers such socially-relevant topics as "the four defilements of human action (i.e., killing, stealing, sexual misconduct and lying), "the six ways of wasting one's personal resources" (i.e. intoxication, slothfulness, loitering in public, attending fairs, being addicted to gambling, keeping bad company and leading an idle existence), the distinctions between good, trustworthy advisors and fraudulent ones, true friends and false friends and most importantly, each person's moral obligations to their primary relationships (i.e., parents, teachers, spouses, friends and companions, masters, ascetics and brahmins) - all of these instructions meant to upgrade and ennoble a person's life in this world.

Another piece of evidence that confirms the Buddha's commitment to include the life of the householder and the professional in his community, is his emphasis on considering all people of every conceivable walk-of-life to be of equal importance and value. Both the monks (bhikkhu-s, bhikkshu-s) and the laity (upasaka-s and upasakaa-s) are instructed to extend compassion,

132

!n but not .Qfthe World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

benevolence and sympathetic joy into all of their social interactions and even in the state of meditation, to cultivate those states of mind that would overcome stupidity, greed, sloth, lassitude, doubt and all forms of selfishness and to extend those charitable states-of-mind to all creatures everywhere.

Given the fact that the disciples of the Buddha (including the arhants who were believed to have achieved the ultimate goal of nirvana), continued to live in the body while still inhabitants of the life-world (samsara) and given the inherently social nature of the Sangha as a corporate institution, some attention had to be paid to the area of human activity that is currently referred to as "economics." Once the Sangha became a relatively sedentary institution, with the monks remaining in one venue for at least three months out of each year, the Sangha required the possession of such goods as land to be occupied by the community, structures to house the monks, physical support (in the form of food, clothing and other appurtenances), and in time, financial support for the production of stupas, temples, other types of holy sites, accommodations for pilgrims to these holy sites, and, of course, a diverse array of visual representations of The Buddha, etc. This institutionalization of the Dhamma, with its concomitant variety of activities and needs, necessitated the creation of a corporate infrastructure, a central part of which involved the organization and management of the economic life of the institution.5

Two Tvpes of Desire6

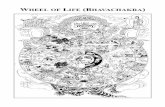

According to the doctrine of the Four Noble Truths, Suffering (duhkha, dukkha), which pervades the whole of creaturely existence in the world of samsara is the offspring of human desire, craving and greed (tanha, trsna). Through the complete eradication of desire and covetousness, one is liberated from the bonds of ignorance, death and rebirth, and, ultimately, the achieves of state of total extinction (nirvana).

But, if an interpreter, whether devotee or scholar, were to take The Buddha's words about desire at face-value, they would, more than likely, derive an excessively narrow, and hence, erroneous interpretation of The Buddha's intended meaning. The question arises: "does The Buddha mean that all human desires, of whatever nature or intentionality, have to be extinguished in order to realize a happy and peaceful life in this world and liberation unto the next world?" Viewing this question within the context of The Buddha's doctrine of the Middle Way, the answer would have to be 'no'. Based on the doctrine of the Middle Way, an intermediate position between egoistic desires and concupiscence, on the one hand, and complete self-denial, on the other, should be identified. And, this is the objective of discussion that follows.

According to The Buddha's instructions, there are two types of desire that lead to different qualities of satisfaction. The first type of desire, tanha, is the longing for objects of pleasure that, at best, yield only incomplete and temporary satisfaction. This form of desire is unacceptable in that it is a by-product of ignorance and blind feelings, desires and cravings, driven by ego-centered pandering to self-interests, often with little or no thought for the impact of any given action upon oneself or others.

133

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism

The second type of desire, chanda, designates a yearning for the general well-being of all sentient creatures and issues from intelligent insight into the nature of things and spiritual wisdom. As such, chanda, is a legitimate part of the pragmatic problem-solving process in everyday life. This type of desire will lead to the realization of well-being, if it is based upon clear-minded intelligence and moral decision-making. Whenever thought and action are motivated by intelligent choices, personal and social well-being, normally, will result. But when motivated by tanha, which is morally blind and transgressive of the basic moral precepts, such action will, inevitably, produce injurious effects upon both the actor and others.

A dramatic contemporary example of this principle would be as follows: the American print and television media have recently reported a disturbing tendency, nationwide, of many corporate CEO's demanding humungous annual salaries and investment benefits or enormous severance packages, often in the tens-of-millions of dollars. This action is often taken at the direct expense of the companies they oversee. In addition, these CEO's often manipulate the financial mechanics of the company in such a way that the shareholders are required to pay the taxes on the CEO's income.. This procedure, ultimately, hurts everyone involved, including the CEO, in terms of due consideration to natural moral retribution or karmic return, or in contemporary parlance, the acknowledgement that "whatever goes around, comes around."

Hence, according to The Buddha, all human endeavor should be a means to elevate and ennoble the life of all sentient beings. Production, consumption and all other forms of economic behavior should be ends in themselves and not means to ulterior, ego-centered goals. These legitimate goals should be developed to promote general well-being within the individual, the community and the environment and the world-at-large.

Hence, as the foregoing discussion clearly indicates, the Buddhist ethic is by no means focused exclusively on the renunciate. The Buddha himself recognized that the acquisition of a reasonable amount of wealth is necessary to the maintenance of a humane mode of life and is, therefore, one of the fundamental rights and privileges of one's birth as a human being. And, as we noted earlier, The Buddha presented many teachings on the proper ways of acquiring wealth. But he always stressed that the purpose of wealth is to facilitate the development of the highest level of human potential, without bringing harm in any form to other creatures.

Viewing the Dharma in its broadest framework, a person is justified in concluding that reasonable material comfort and economic security are only a foundation for seeking two loftier goals: mental equanimity and spiritual freedom. The "bottom line" of this matter, to invoke a contemporary corporate "sacred cow," is that the essence of the Buddhist approach to the economic life rests in ensuring that all economic endeavors, of whatever magnitude and nature, should serve to enhance the quality of human life, in all its diverse dimensions.

134

1.n but not .Qf the World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

The Role of Ethics in the Buddhist Economic Life

If one were to interpret, at face-value, the ethic and the ethos of the predominant consumer ethic that is currently spreading over much of the globe, the resulting life principle would be that "the good life" is defined as the acquisition of desired goods that, ostensibly, are believed to be capable of bringing momentary pleasure, if not long-term happiness. Hence, according to this life-ethic, happiness comes primarily, if not exclusively, from the acquisition and possession of material goods. By implication, this social posture ignores a deeper moral and spiritual principle that a person might expect to experience an even greater degree of happiness by giving up something, with no promise of receiving anything in return of comparable or superior value. In contrast to the ethic of acquisition and possession, this is the ethic of personal sacrifice and selfdenial. For example satisfaction by giving up something on behalf of their loved-one(s), rather than by acquiring a desired commodity, whether of a physical, moral or emotional nature.

Another factor that modem economists and business people view as decisive in the production, distribution and consumption of goods, is the principle of supply and demand. There are some, no doubt, who see demand as the single overriding determining factor in the production, pricing and selling of goods and this, to the exclusion of any and all ethical considerations. In his work entitled, Buddhist Economics. A Middle Way for the Marketplace,7 Ven. R. A. Payutto asserts that the principal of demand is of relative importance and only then, under certain social and economic conditions. He illustrates the irrational application of the principle of demand by the story of two men shipwrecked on a desert island. One has a sack of rice and the other a hundred gold necklaces. Under normal circumstances, a single gold necklace would be enough, more than enough, to buy a whole sack of rice. But now the two men find themselves stranded on the island with no tangible means of escape and no guarantee of rescue. The value of the two types of goods changes. Now the person with the rice is in a position to demand all one-hundred gold necklaces for a mere portion of rice, or he might refuse to make the exchange at all.

Ven. Payutto continues: "However the question of ethics does not come up within the context of the story. Economists may assert that economics concerns itself with demand, not its ethical quality, but in fact ethical considerations do affect demand. In the example of the two shipwrecked men, there are other possibilities besides trade. The mail with the gold necklaces might steal some of the rice while the owner is not watching, or he might just kill him in order to get the whole sack. On the other hand, the two men might become friends and help each other out, sharing the rice until it's all gone, so that there is no need for any buying or selling at all. 8

In The Buddha's view, no questions concerning any aspect of economics are, exclusively, economic in nature, altogether devoid of historical, social and moral implications. Stated positively, the planning and management of all commercial ventures, of whatever size and nature, must include a consideration of all pertinent ethical factors, if any given venture is to produce moral and humane

135

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism

results. And this principle holds true with regard to both short-term and longterm consequences.

The Ethic of the Householder

While a major portion of the Buddha's teaching are directed toward his monastic followers, there is no sign that he was concerned exclusively with them or that he wished for all people to become monks and nuns. All indications are that he established the Sangha as an independent community that would exist as an embodiment of the dhammma, and an institution that would nourish society with the teachings of the dhamma and thereby, serve as a moral and spiritual model which would serve as the ethical basis for non-monastics.

The Suttas contain significant blocks of materials in which The Buddha instructs various types of people in a diverse array of life-situations on how to comport themselves according to the requirements of the Dhamma and on the appropriate bases for the acquisition and enjoyment of wealth.9

Concerning the acquisition of wealth, he declares that all forrhs of exploitation and the abusive treatments of others should be avoided, such that wealth is acquired and managed in a morally upright manner. The intelligent and righteous merchant should take proper measures to protect his possessions against loss or theft, on behalf of the long-term development of his business and as a protection against any kind of misfortune. Any excess wealth, over and above the provision of life's necessities, should be contributed toward the support of general social welfare. And, finally, with regard to one's mental attitude toward personal and familial wealth, one should, under all circumstances, maintain a balanced and equitable frame of mind, never becoming anxious or obsessive about the acquisition, increase or retention of one's possessions.

The Buddha held in high regard only those persons who obtained their wealth by means of their own honest ingenuity and who used it wisely, and toward beneficial ends. "That is, the Buddha praised the quality of goodness and benefit more than wealth itself."10

Moreover, the moral person should maintain a high and steady sense of duty in both household or business affairs. It is recognized in the tradition that such a person can expect, through cogent planning and conscientious efforts, to be successful and happy in all ventures they choose to pursue.

The Buddha presented reasons why a moral person should strive for and acquire personal and familial wealth -- by means of diligent effort and clearheaded effort: (1) he should be able to bring happiness to himself, his family, his servants and his workers, (2) he should be able to gladden the hearts of his friends, colleagues and companions, (3) he should be able to protect his property from destruction by fire, theft, water, enemies and greedy heirs, (4) he should be in a position to make efficacious offerings to his relatives, guests, ancestors (pretas), kings and devas, and (5) he should be in a position to present offerings to ascetics, monastics, and other types of recluses who have dedicated themselves completely to the cultivation and propagation of all dharmic principles and to the achievement of complete perfection.11

136

1n but notQfthe World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

Whether he does or does not, in fact, achieve a high degree of wealth and success, the person who pursues all business ventures with noble and purehearted intentions, can rest in the assurance that the means employed toward his goals were honorable and that he gave the pursuit his best effort. Further, a personal knowledge of the implications of the Dhamma for life, will include an understanding that certain, perhaps, unknown cosmic (i.e., karmic) forces are always in the mix, causal factors created not only in the present lifetime, but in previous lifetimes, as well. If he does realize an appreciable amount of wealth and success by respectable and honorable means and by his own conscientious efforts, he is encouraged to enjoy ownership of his possessions, freedom from indebtedness, a sense of general well-being and blamelessness.12 Socially, all persons with whom he has dealings (including family, servants, workers, as well as, recluses and priests) will look upon him as an honorable and upstanding man, a virtuous supporter of his extended family and a responsible member of the community. And, he can expect, thereby, to live a long and happy life and by means of his wealth, enjoy a consideration amount of success and social standing and, thereby, avoid falling victim to life's fortuitous circumstances.13

However, there are a number of forms of livelihood that the householder should avoid pursuing because of their lack of conformity with the fifth step of the Noble Eight-fold Path (i.e., Right Livelihood)14 and the Five Precepts.15

These forbidden profess-ions include the manufacture of weaponry, the sale of human beings, the slaughtering and selling of animal flesh, and the distribution of intoxicants and poisons.16 (Were The Buddha to be present in the current world in an embodied form, his list of forbidden types of livelihood might also include all forms of international terrorism and many forms of international corporate acquisitions and takeovers, as well as, the exploitation of cheap labor.) A business person should always be alert, knowledgeable in his business and honest in all of his dealings. Provision is also made on behalf of those of modest means, to start a small business and to do everything in their power to grow it into a larger enterprise. According to the Cullasetthi Jataka, "By means of the accumulation of small money, the wise man establishes himself, even as by skillful application, small particles are fanned into a fire."17

After attaining a degree of success and wealth, a person should apply all of his skills to the maintenance of that status. The Buddha himself mentions four potential reasons for failure to do so: (1) negligence in seeking what has been lost (or, failure to maintain crucial business operations, effectively), (2) failure to repair what has become decayed (or, failure to keep the business in good running order), (3) eating and drinking to excess, (both of which may lead to slothfulness and poor business judgments), and (4) placing unskilled and unreliable people in places of responsibility (or, failure to exercise wise and judicious judgments in the hiring and firing of employees).18

The business person is enjoined, once he has gained and solidified his wealth, to avoid hoarding his possessions or putting them to selfish and injurious ends. It is said of the miser: "At no time whatever does he get himself clothing, food, garlands, or perfumes, nor does he give any to his relatives. He guards them, crying: 'Mine! Mine!' Then rulers, thieves, his heirs, having taken his

137

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism

wealth, go away in disgust. Yet still he cries, 'Mine! Mine!' as before. The wise man, having acquired wealth, helps his relatives and gains their respect; after

death he rejoices in a heavenly region."19

As a summation of his view of the ethic of the householder, the Buddha instructs his disciplines on the "profitability" of carefully and meticulously cultivating a life of high ideals based firmly upon solid moral principles. He

states that there are five advantages to the pursuit of a life pervaded by moral rectitude. They are as follows: (1) through careful attention to his affairs he gains

a great deal of wealth, (2) he achieves a solid reputation for morality and good conduct, (3) whatever social group he associates with, whether warriors, Brahmins, householders, or ascetics, he does so with confidence and assurance,

(4) he dies unconfused, and (5) after death, following the dissolution of the body, he arrives at a good place, a heavenly world.20

Distinguishing Character Traits of the Successful Monk and Layperson

The Buddha frequently discoursed, either separately or together, on two

distinctly diffedrent but complementery, sets of ethical principles: those of the monks and those of the layperson.

On one occasion, The Buddha drew a clear distinction between the ethical principles by the cultivation of which the monastic and the layperson achieve success in their respective areas of endeavor. He, first of all, declares that a

merchant who possesses three defining characteristics (i.e., shrewdness, maximum capability and ability to inspire confidence in others), will, in short order, attain greatness and increased his store of wealth. He, then, goes on to spell out specifically in what fashion the diligent merchant manifests these three positive traits of character: (1) shrewdness (cakkumaa), by maintaining a

masterful knowledge of his merchandise, such that he is able to predict the variances between purchase price, sale price and margin of profit, (2) maximum capability (uttama-dhuro), by becoming resourceful in his skills in buying and

selling goods, and (3) inspiring confidence in others (nissaya-sampanno), by gaining an admirable reputation among well-to-do householders that he is a "merchant . . . who is shrewd, extremely capable and resourceful, competent to

support sons and wife, such that is able, periodically, to pay interest (anuppadaatua) on money loaned. Inspired by his impressive skills as a

merchant and his high moral character, financial backers will eagerly loan him money to finance his business, was the Buddha's belief.

For his part, the monk will also, in short order, achieve greatness and a . significant increase in his "profitable states,'' by possessing the same three traits

of character (again, shrewdness, maximum capability and ability to inspire confidence in others). The monk attains the capacity for shrewdness by coming

to know, truly, the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path (i.e., the nature of

suffering, the origins of suffering, the cessation of suffering and the only effective way of escaping from suffering). He achieves maximum capability by "living firmly rooted in energy /or "vigor"/, by avoiding unprofitable states and creating profitable states, he becomes stout and strong to struggle, without avoiding

138

.ln but not Qf the World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

challenges even in good times." Finally, he is capable of inspiring confidence in others by associating with monks of broad knowledge, well-versed in the Sayings (agata-gamaa), who know the Outline thoroughly, who know the discipline (vinaya) and the summaries (matika, Skt., matrkaa-s) by heart. By continually manifesting before his teachers an inquiring mind and heart with regard to the deeper meanings of all their teachings, "These holy teachers then open up to him what had been closed, make clear what had been obscure and assist him in resolving his doubts on all manner of issues."

It is quite apparent from the foregoing, that The Buddha held in high regard the three virtues of shrewdness, maximum capability and the ability to inspire confidence in others, regardless of the nature of the course of one's life, whether lay or monastic and that he assiduously urged all of his followers to cultivate these virtues, such that, that monk or layperson who successfully acquires these three virtues, will "in short order achieve greatness and an increase in profitable states."

Centrality of Human Action in Determining the

Acquisition of Success and Wealth

A Brahmin student named Subha came to Gotama seeking instruction concerning the Dhamma. He asked specifically: ". . . what is the cause and condition why human beings are seen to be inferior and superior ? ... short-lived and long-lived ... sickly and healthy ... ugly and beautiful ... influential and uninfluential, poor and wealthy ... low-born and high-born ... stupid and wise, etc.?" Gotama responded: "Student, beings are owners of their actions, heirs of their actions; they originate from their actions, are bound to their actions, have their actions as their refuge. It is action that distinguishes beings as inferior and superior." Gotama then describes a series of persons with antithetical types of karma (one who kills vs one who refrains from killing, one who injures others vs one who refrains from injuring others, one who is envious of others vs one who is not en- vious, etc.) In each case, the producers of evil karma who do not renounce their evil ways while still in the world, are reborn in this world, in a state commensurate with the nature of their evil karma (i.e., a person who kills another returns as a person who is short-lived, a person who is angry and irritable is reborn as an ugly person, etc.). People who manage to renounce their evil ways either go to "a happy destination " (i.e., heaven ) or, if reborn, return to an improved destiny (e.g. a person who refrains from anger and irritation, "whenever they are reborn they are beautiful ").

The Buddha's most pertinent teaching.concerning the topic of wealth and success is as follows:

Here, student, some man or woman does not give food, drink, clothing carriages, garlands ... etc., to recluses or brahmins. Because of performing and undertaking such action ... he reappears in a state of deprivation ... But if instead he comes back to the human

state, then wherever he is reborn he is poor. This is the way, student, that leads to poverty, namely, one does not give food ... and lamps to recluses or brahmins.

139

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism

But here, student, some man or woman gives food . .. and lamps to

recluses or brahmins. Because of performing and undertaking such action . . . he reappears in a happy destination . .. But if instead he

comes back to the human state, then wherever he is reborn he is wealthy. This is the way, student, that leads to wealth, namely, one gives food ... and lamps to recluses or brahmins. /emphasis added/2

The implications of this passage for our understanding of The Buddha's view of the dhamma-centered acquisition of success and wealth or the failure to do so, are numerous: (1) in contrast to traditions that believe that each human being is born and dies only once, in Buddhism, it is assumed that each person has lived before and will live again, until such time as they achieve liberation into nirvana; (2) hence, a person's birth status during any given lifetime, is not,

exclusively, the result of family genetics or biological development (although those factors may be involved) but is also the result of the moral and spiritual "capital" accrued by that person in the course of all previous lifetimes; hence, (3)

a person's relative achievement of success and wealth during any given lifetime will be dependent, not only upon his current life-circumstances -- for example, his quality of birth, his level of skillfulness and ambition and the amounts of good fortune and misfortune in his life -- but also the sum-total of his karmic stock that he brings into the world from previous lifetimes.

It would be fruitful to contrast this karmic view of human life with the idealistic American notion that any person, regardless of the social circumstances into which they are born, can get ahead in life and become successful and wealthy (or, at least, reasonably comfortable), if they are sufficiently intelligent and possess sufficient stores of ambition, perseverance and the capacity for hard work. By contrast, according to The Buddha's notion of karma and rebirth, a person does not "start from scratch" at birth but brings in with him at birth a certain amount of "moral and spiritual baggage," factors that deter-mine, not only the quality of their birth but their physical characteristics, social status, moral

character and overall potential for the future acquisition of success and wealth. Hence, because of the impact of karma and rebirth in determining the nature of every life-situation, the Buddhist understanding of the pursuit of life-goals in this

world is far more complicated than the, so-called, Western view. But, based on the determinative power of the moral and spiritual quality of one's action during

any given lifetime, all people are born with the freedom and the potential capacity

��������&���������� actions.

Profitable Possessions in this World and in the World Beyond23

As we have clearly observed from the above presentation, in the eyes of The

Buddha, a lay person has every right and obligation to pursue a variety of goals that will bring him, his family, friends, employees and associates an acceptable degree of wealth, comfort and satisfaction. While only those who commit themselves full-time to the pursuit of the bliss of complete liberation from ignorance and rebirth, the worldling who patterns his life on the basis of the

140

In but not Qf the World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

Dhamma, taking refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha, committing himself to the promotion of the general well-being of himself, his family and society-atlarge, all the while obedient to the teachings of The Buddha, can expect, if not ultimate liberation, then a reasonably happy and comfortable life in this world, and in the end, a transition to heaven and a fortunate rebirth in this world, next time around. In fact, The Buddha taught that the basic physical needs must be met before genuine spiritual development, realistically, can begin. /More on this matter below. I

As one text states the matter, succinctly: "A wise man keeps the moral precepts, eager for three forms of happiness: approbation, wealth, and after death, the joy of heaven. 24

Of course, in the end, whatever possessions, wealth, social status and reputation a person may have gained during his lifetime, at the time of death, all must be left behind. The German philosopher, Martin Heidegger, observes in his masterwork, Being and Time, that it is the reality of death that defines both the possibilities and the limitations of human existence and it is also, the reality of death that gives to everything in the Life World /Lebenwelt) whatever meaning and value it possesses. This insight, I believe, is also applicable to the Buddha's worldview. In any case, the question was often put to him as to whether there was anything in the world of samsara that could produce profitable results in the World Beyond. The Buddha's response to that question put to him on one occasion by King Pasenadi, was in the form of a single word: "Vigilance" ( appamaada )25

He, then, adds an illuminating story26 to further illustrate the prospects of achieving profitable results in the World Beyond by means of certain courses of action taken in this world:27 On one occasion when the Buddha was staying at the market town of Kakkarapatta, he was approached by one Dighajanu who, remarking that he and other householders were absorbed in the affairs of the present world, requested that the Buddha preach the Dhamma to people like himself. He added that they "wished to know the things that would be of advantage to them in the future world." The Buddha, first all, gave them the four things that lead to happiness in the present world: attainment of energy (uttanasam-padaad), attainment of watchfulness (aarakkaha-sampadaa),

association with people of high moral standing (kalyaa-namittataa), and the leading of a balanced life (samaji-vikataa).28 By "acquisition of energy" he meant to be skillful and industrious, to develop an inquiring mind and to be conscientious in carrying out the work to be done. By "attainment of watchfulness," he meant to guard carefully one's possessions, so that they are never stolen or destroyed. By "associating with friends of high moral standing," he indicated that one should cultivate such virtues as confidence (saddhaa), morality (sila), generosity (caaga) and wisdom (panna) in one's dealings with other people. As for "leading a balanced life," one should never become either too elated or too discouraged about one's life situations and in addition, always live comfortably within one's income.

The Buddha then spoke of four virtues that might produce welfare and happiness in the World Beyond. They are: (1) confidence (vishvaasah) based on

141

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism

intelligence and exper-ience, (2) morality (sila, (3) generosity or charity (dana) and (4) wisdom (panna, prajna). The word "confidence" seems to refer to unfailing belief in the truthfulness and authenticity of the teachings of The Buddha. "Morality" results from practicing the precepts. "Generosity" and "charity" result from freeing oneself from greed and the practice of denying oneself non-essentials. Finally, "wisdom" is the byproduct of "the rise of that wisdom leading to welfare, and to the penetration of the noble way leading to the total destruction of suffering. "29

There is an illuminating story in the Dh.A. (III. 262) that illustrates the fact that basic physical hunger can be both a cause of suffering and an obstacle to spiritual progress and that the satisfaction of physical hunger can render a person receptive to instructions in the Dhamma. Quite often, in the Suttas, the Buddha is represented as providing a meal for his audience before beginning his discourse. He understood clearly how difficult it is to appreciate the Dhamma on an empty stomach. In the words of one contemporary author:

Although consumption and economic wealth are important, they are not goals in themselves, but are merely the foundations for human development and the enhancement of the quality of life. They allow us to realize the profound: after eating, the peasant listened to Dhamma and became enlightened. Buddhist economics ensures that the creation of wealth leads to a life in which people can develop their potentials and increase in goodness. Quality of life,

rather than wealth for its own sake, is the goa!.30

Most instructive for our purposes here, The Buddha closed one of his addresses with the following gaathaas:

From rising and taking action, arranging his matters with care, He who is vigilant orders his living, guards and protects his wares.

With confident understanding, moral and willing to hear, Free from the taint of the niggard, he clears a continuous road Leading to things that are excellent, things of the world beyond. By one who is named the "Truth," there are declared eight things To bring the understanding layman present joy And joy in the future worlds. For increased merit Let him be generous, happy to make a gift. 31

To Ugga, the King's chief minister, the Buddha proclaimed seven existential states that are incorruptible:

The riches of confidence, riches of morals, of shame and fear of wrong-doing, The riches of listening, of charity, and wisdom are seven. Whoever possesses these riches, or woman or man, That one is invincible either to devas or men. Because confidence, morals are brightness, the vision of Truth, Give yourselves up, wise one, to remembering

That which the Buddha has taught.32

142

In but not Qf the World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

Concluding Statement

We believe that the materials discussed in this paper, provide ample demonstra-tion that the Buddha was concerned to provide moral and spiritual

principles, not only for the achievement of spiritual liberation by the religious elite, but also for the general enhancement of the lives of the great mass of people in this world. But, these two ethics, to be properly understood, have to be viewed as interlinked constituents of a larger worldview. And, it seems equally clear that, in the Buddhist tradition, the cultivation of moral principles (sila) is a precondition for the worldly life of the layperson and, as well as, the spiritual path of the renunciate. Taken together, these two ethics provide a com-pelling exemplification of the meaning of the principle: "be in but not of the world."

Davis, Wins ton

Robertson, Roland

Saddhatissa, Hammalawa

Schopen, Gregory

Walshe, Maurice

Warder, A. K.

Payutto, R. A. n.d.

2005

2005

1977

1997

2004

1995

Bibliography

"Wealth," Encyclopedia of Religion, (2nd ed.), Lindsay Jones, ed., 9707-10.

"Economics and Religion," Encyclopedia of Religion, (2nd ed.), Lindsay Jones, ed., 2668-2677

Buddhist Ethics. Boston: Wisdom Publications.

"The Buddha as an Owner of Property and Permanent Resident in Medieval Indian Monasteries," in Gregory Schopen, Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks. Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India. University of Hawaii Press, 258-90.

Buddhist Monks and Business Matters. Still More Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India. (Studies in the Buddhist Traditions, Series), Honolulu: University ofHawai'i Press, 2004

The Long Discourses of the Buddha. (Diigha Nikaya)

Boston: Wisdom Publications.

1995 The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha. (Majjhima Nikaya) Boston: Wisdom Publications.

2000 The Connected Discourses of the Buddha. (Samyutta

Nikaya) Boston: Wisdom Publications.

2000 Indian Buddhism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

Buddhist Economics. A Middle Way for theMarketplace. trans. by Dhammavijaya and Bruce Evans. www.geocities .

. com/Athens/Academy/9280/econ.htm.

143

Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism

References

1. Bhikkhu Bodhi has produced an immensely useful compendium of primary source material drawn from the Pali tradition, entitled, In the Buddha's Words. An Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon, with a Foreword by the Dalai Lama (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2005). To make the selected materials readily available to those students of Buddhism who do not read Pali, he has organized the materials around ten topical themes. Section IV includes a wealth of teachings of the Buddha under the heading, "The Happiness Visible in This Present Life," concerning numerous topics relating to life in this world: family ethics, right livelihood, material well-being in this life and spiritual wel fare in the world beyond, morally upright methods of acquiring, retaining and using appropriately all worldly goods, etc. 2· Warder 153

3· XVI. 1.4-5

4· Walshe 231-2

5· Concerning the topics of business affairs and economics in the early Sangha, consult an outstanding collection of papers by Gregory Schopen, Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks. Collected Papers on the Archaeology, Epigraphy, and Texts of Monastic Buddhism in India (The University of Hawaii Press, 1997) and Buddhist Monks and Business Matters. Still More Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India (The University of Hawaii Press, 2004). Notice should be taken of the fact that "economics" as an independent, scientifically-defined and specialized area of study arose only during the l 91h

century, and principally as a result of the publication of Adam Smith's magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations. It is also noteworthy, that economics arose as an intellectual specialization, concurrently with the spread of secularism and the, concomitant diminishment of the importance ofreligion as a cultural force. Concerning more details about this topic, see Roland Robertson, "Economics and Religion," Encyclopedia of Religion, Lindsay Jones, ed., 2668-77. 6· I am indebted to Ven. P.A. Payutto's excellent short work, entitled, Buddhist Economics. A Middle Way for the Market Place. (www.geocities.com/Athens/ Academy/9280/econ.htm.) for this distinction between two types of desire. 1· Payutto, Chapter V. 8· Ibid., Chapter V 9· DNIII. 188 10· Payutto, Chapter V I I. AN III. 45f. 12

· AN II 69f. 13· AN III 75-78 14· For a full discourse on the Eightfold Path, consult the Mahaacattarisaka Sutta or. "The Great Forty," (MN 117. 28-33). In the course of delivering this teaching, The Buddha elaborates on the nature ofright and wrong types oflivelihood: "And what, bhikkhus, is wrong livelihood? Scheming, talking, hinting, belittling, pursuing gain with gain: this is wrong livelihood. Right livelihood, I say, is twofold: there is right livelihood that is unaffected by taints, partaking of merit, ripening on the side of attachment; and there is right livelihood that is noble, taintless, supramundane, a factor of the path." (CXVII. 29-30) 15· The five precepts are: refrain from killing living beings, refrain from taking what is not offered, refrain from illicit sexual relations, refrain from telling falsehoods, and refrain from all consumption of alcoholic beverages. 16· AN III. 208 17· Jataka I. 122, quoted in Saddhatissa I 08 18· AN II. 249

144

ill but not .Qf the World: The Buddha's Teachings Concerning the Economic Life

19· Jataka III. 302, quoted in Saddhatissa, 108

20· Mahaaparinibbana Sutta 1. 24

21. AN III. 249

22· MN 135

23· Concerning the place of the possession of wealth in religion, generally, consult, Roland Robertson, "Economics and Religion," Encyclopedia of Religion. Lindsay Jones, ed., 2668-77 and Winston Davis, "Wealth," Ibid., 9707-10

24· Udanavarga 6. 1, cited in Strong 115

25· Samyutta Nikaya I. 87 26· Anguttara Nikaya IV. 281-85 27· I am indebted to Hammalawa Saddhatissa for his account of the materials that follow and have presented them here, largely as he presents them in his book, Buddhist Ethics, 109-111.

28 ANIV. 281-85

29· DNIII. 237, 268

30· Payutto, Chapter V 31. ANIV. 285, quoted in Saddhatissa 110

32· AV IV. 6f., quoted in Saddhatissa 111

145