Illuminate No 24 June 2015

-

Upload

pinkanbobo -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

2

Transcript of Illuminate No 24 June 2015

-

Institute researchers have discovered the protein MCL-1 is critical for keeping milk-producing breast cells alive and sustaining milk production in the breast.

Scientists Dr Nai Yang Fu, Professor Geoff Lindeman and Professor Jane Visvader found that MCL-1, a critical cell survival protein that has also been implicated in cancer development, plays an essential role in normal breast development.

Unlocking cancer secretsThe research team showed that MCL-1 levels

increased dramatically in the breast within 12 hours of giving birth, determining that stem cells and luminal cells were the breast cells that most critically rely on MCL-1.

A number of recent studies at the institute have shown MCL-1 is important for the survival of certain immune cells, as well as the survival and growth of cancers such as leukaemias andlymphomas.

Our team has previously implicated both stem cells and luminal cells in some types of breast cancer, Professor Visvader said. Our research raises the question of whether MCL-1 is an important target for developing anti-cancer drugs for breast cancer.

Integral for cell survivalProfessor Visvader said MCL-1 was one of the

key survival factors in the mammary gland.MCL-1 is important for all stages of breast

development, from puberty to pregnancy and lactation, she said. Based on this discovery, it is reasonable to believe that every mammal requires MCL-1 for milk production and, ultimately, the survival of their offspring.

Professor Lindeman, Professor Visvader and their breast cancer research team have spent the past 15 years unravelling the secrets of normal breast development in a bid to improve our understanding, and ultimately treatment, of breastcancer.

This is an exciting time for our research team, Professor Visvader said. Some of the discoveries we have made regarding breast development and how it goes awry in cancer have helped to identify potential targets for therapy, leading to preclinical studies and clinical trials aimed at breast cancer treatment or prevention.

2

3

4

56

7

8

In this issue

Follow us

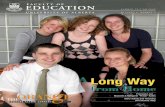

Professor Geoff Lindeman, Professor Jane Visvader and Dr Nai Yang Fu (L-R) discovered the survival protein MCL-1 is critical for breast milk production.

From the directorProfessor Doug Hilton on the institutes new strategic plan and inaugural Metcalfscholars.

NHMRC funds malaria vaccine search$11.6M funding to translate malaria discoveries into treatments.

Drug-like molecule could treatMSAnti-inflammatory molecule suppresses inflammation in MS models.

Editing out cancerNew genome editing technology developed to kill blood cancers.

Recognising research excellenceFour institute researchers inducted into the Australian Academy of Health and MedicalSciences.

Staff profilesPostdoctoral researcher Dr Fansuo Geng PhD student Ms Melanie Williams

Dying to surviveCould new treatments for chronic infectious diseases lie in controlling celldeath?

Anti-cancer drug could affect blood cellrecoveryPromising target for cancer therapy found to be crucial for blood cell production.

Gene architects guide embryo developmentTwo proteins identified that ensure embryonic growth follows the plan.

Investing in the next generation through Centenary FellowshipsGenerous donations fund our first 10Centenary fellows.

$40k for research into childhood coeliac diseaseCoeliac Victoria and Tasmania support leading coeliac disease studies.

Centenary update

Coming events This is an exciting

time for our researchteam.

Milk protein couldunlock breast cancersecrets

I L L U M I N A T EIssue Number 24 | June 2015

S U P P O R T O U R R E S E A R C H w w w . w e h i . e d u . a u

www.wehi.edu.au WEHIresearch WEHIalumni @WEHI_research WEHImovies Walter and Eliza Hall Institute

-

$11.6M to search for malaria vaccineThe institutes quest to develop a vaccine for malaria received an $11.6 million boost in the recent National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funding round.

Aiding the Asia-PacificInstitute researchers Professor Alan Cowman

and Professor Ivo Mueller, together with colleagues at the Burnet Institute and The University of Melbourne, were awarded $10.9 million over five years to progress the development of novel malaria treatments.

Professor Cowman said the program would focus on the malaria strain Plasmodium vivax. Plasmodium vivax is a significant cause of disease in Asia and the Pacific, with up to 2.5 billion people at risk, he said.

This grant will be used to enable the translation of our teams discoveries into potential new vaccines and antimalarial drugs that can be progressed to clinical trials.

A vaccine for all malaria?Professor Louis Schofield said malaria

eradication was the ultimate goal for any malaria vaccine approach.

However the complexity of the parasites biology and lifecycle make it extremely difficult for a single vaccine to be universally effective, Professor Schofield said.

His team was awarded more than $750,000 by the NHMRC to progress a vaccine that could potentially be effective against all species, stages and strains of the malaria parasite.

Excitingly, we have found a part of the malaria parasite that is conserved across all species and has been able to kill all the main stages of malaria in models. This funding will help us progress our vaccine to the point of human clinical trials, hopefully within three years, Professor Schofield said.

maintaining a sustainable organisation that provides the funding and services necessary for our research to prosper.

I would like to thank our supporters who contributed to the development of the plan, making the next era of research discoveries possible at the institute.

Inaugural Metcalf scholarsA key pillar of our strategic plan focuses on

the role of supporting the institutes staff and students for our future success. It was with great pride that we announced the recipients of the inaugural Metcalf Scholarships, made possible by generous donations from many in the institute community in memory of Professor Don Metcalf. These contributions have formed a fund that will support young scientists into the future. Our first Metcalf scholars Kimberley Callaghan, Adam Lipszyc and Madeleine Dawson are undergraduate students with enormous potential and will work on projects in cancer and infectious diseases. Tax-deductible donations can be directed to the Metcalf Scholarship Fund.

Thank you to the Coolah Lady Golfers

Medical research advances can take years and even decades, so we are very grateful to our supporters who have stuck with us over the long term. A wonderful example is the Coolah Lady Golfers, who have been raising funds for our research for 40 years. Since 1975, this New South Wales group has contributed more than $80,000, providing our researchers with encouragement and inspiration. We are proud that we have been able to reward the Coolah Lady Golfers dedication and perseverance with research outcomes that have improved the lives of people living with cancer, immune disorders and infectious diseases.

Very best wishes, Doug

May was a noteworthy month both for the institute and for the Australian medical research sector. It was pleasing that the Australian Government laid out a clear timetable for the establishment of the Medical Research Future Fund, and how the fund will be fully capitalised to $20 billion by 2020. I am very excited about how this game-changing fund will bolster Australias medical research sector to meet its current and futurechallenges.

Closer to home, I was delighted to welcome many of our supporters and alumni to the institutes recent Annual General Meeting (AGM). In our centenary year, the AGM showcased exciting developments that will underpin the institutes success into the future.

A plan for shared successAn important part of our AGM was the launch

of the institutes Strategic Plan 2015-2020. This plan provides a clear direction for the institutes ongoing operations and was developed around the themes of: doing great science, with a focus on our core

strengths of cancer, immune disorders and infectious diseases;

attracting and developing exceptional people; securing the support we need; and

Associate Professor Mike Lawrence

Members of the institutes malaria research team

From the director

$20M microscopy facility to visualise molecular world

Melbourne scientists now have access to an unparalleled view of the molecular world thanks to Australias first advanced structural cryo-electron microscopy centre.

The Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Centre for Structural Cryo-Electron Microscopy was launched earlier this year, and is located at Monash University, Clayton.

Associate Professor Mike Lawrence will coordinate the institutes role as a foundation partner in the centre. The centre features a $5 million Titan Krios cryo-electron microscope, which is powerful enough to resolve three-dimensional molecular shapes and structures with detailed precision, creating exquisite models of important biological molecules.

Investigating insulins actionAssociate Professor Lawrence said the centre

would help in his quest to better visualise how insulin binds to its receptor, which was crucial to understanding how diabetes developed.

The structure of insulin has been known for many decades, however we have only recently determined how insulin binds to its receptor, he said. This new technology will enable us to create three-dimensional structures of the whole insulin receptor, vastly improving our understanding of this critical molecule.

The Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Centre for Structural Cryo-Electron Microscopy is jointly funded by the Ramaciotti Foundations, Australian Research Council, Monash University, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, La Trobe University and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

S U P P O R T O U R R E S E A R C H w w w . w e h i . e d u . a uP a g e 2

Around the institute

-

Genome editing technology to aid blood cancer treatmentInstitute researchers have developed a new genome editing technology that can target and kill blood cancer cells with high accuracy.

Dr Brandon Aubrey, Dr Gemma Kelly and Dr Marco Herold used the technology to kill human lymphoma cells by locating and deleting an essential gene for cancer cell survival. The research provides a proof of concept for using the technology as a direct treatment for human diseases arising from genetic errors.

Mimicking blood cancerThe team adapted the technology, called CRISPR,

to specifically mimic and study blood cancers.Dr Aubrey, who is also a haematologist at The

Royal Melbourne Hospital, said the team used the CRISPR technology to target and directly

manipulate genes in blood cancer cells, showing for the first time its potential in cancer therapy.

Using preclinical models, we were able to kill human Burkitt lymphoma cells by deleting MCL1, a gene that has been shown to keep cancer cells alive, he said. Our study showed that the CRISPR technology can directly kill cancer cells by targeting factors that are essential for their survival and growth. As a clinician, it is very exciting to see the prospect of new technology that could in the future provide new treatment options for cancer patients.

The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute has one of the most advanced CRISPR laboratories in Australia, established and led by Dr Herold. The technology has many advantages over existing tools, allowing us to speed up discoveries that could be translated to better diagnostics and treatments for the community, Dr Herold said.

Walter and Eliza Hall Institute scientists have developed a new drug-like molecule that can halt inflammation and has shown promise in preventing the progression of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory disease that damages the central nervous system including the brain, spinal cord and optic nerves. There is no cure and there is a desperate need for new and better treatments.

Dr Ueli Nachbur, Associate Professor John Silke, Associate Professor Guillaume Lessene, Professor Andrew Lew and colleagues developed the molecule to inhibit a key signal that triggers inflammation.

Reducing collateral damageInflammatory diseases such as MS were

triggered by an over-active immune system, Dr Nachbur said. Inflammation results when our immune cells release hormones called cytokines, which is a normal response to disease, he said.

However when too many cytokines are produced,

inflammation can get out of control and damage our own body, which is a hallmark of immune or inflammatory diseases.

To apply the brakes on this runaway immune response, institute researchers developed a small drug-like molecule called WEHI-345 that binds to and inhibits a key immune signalling protein called RIPK2. This prevents the release of inflammatory cytokines that attack and damage tissues in autoimmune diseases.

Professor Lew said the team examined WEHI-345s potential to treat MS in experimental models of the disease.

We treated preclinical models with WEHI-345 after symptoms of disease first appeared, and found WEHI-345 could prevent further progression of MS in 50 per cent of cases, he said. These results are extremely important, as there are currently no good preventive treatments for MS.

Developing new treatmentsAssociate Professor Lessene, who developed

the molecule with colleagues in the institutes ACRF Chemical Biology division, said WEHI-345 had potential as an anti-inflammatory agent.

This molecule will be a great starting point for a drug-discovery program that may one day lead to new treatments for MS and other inflammatory diseases, Associate Professor Lessene said.

Dr Nachbur said institute scientists would use WEHI-345 to develop a better, stronger inhibitor of RIPK2 for treating inflammatory disease. Not only is this a potential new treatment, it is a great tool to unravel this signalling pathway and identify other important proteins that control inflammation that could be a drug target, Dr Nachbur said.

Associate Professor Guillaume Lessene, Professor Andrew Lew, Dr Ueli Nachbur (L-R) and colleagues developed a new drug-like molecule that halts progression of multiple sclerosis.

Dr Gemma Kelly, Dr Brandon Aubrey and Dr Marco Herold (L-R)

[We] found WEHI-345 could prevent further progression of MS in 50 per cent of cases.

Anti-inflammatory molecule could treat MS

S U P P O R T O U R R E S E A R C H w w w . w e h i . e d u . a u P a g e 3

Rese

arch

new

s

-

Dr Fansuo Geng Postdoctoral scientistDescribe your job I work on understanding the genes responsible for intestinal development. We think these genes are likely to play a role in bowel cancer development as well.

If you werent doing your job, what would you be doing? As a kid, I wanted to be a mathematician. When I was in high school, I was obsessed with solving math problems.

Best aspect of your job? There are many scientists with diverse expertise working here. It is great to be able to pick their brains!

Worst aspect of your job? That I cannot be the administrator of my computer at work!

Whats one thing most people would be surprised to know about you? Despite having a massive vocabulary, I am a non-native English speaker. My hobby is learning new words from books and newspapers every single day!

Whats the smartest thing youve been told? Iread somewhere that you can place a dollar sign in front of every additional word you learn. Iam hoping that with each new word I master, Iwill get a salary increase of $1!

Best things about living in Melbourne? Walking to work and the numerous parks scattered around the city.

Your favourite overseas destination? Fiji. I like the feeling that its in the middle of nowhere.

Who do you most admire? Bruce Lee.What do you want to be remembered for? Mycontribution to science.

Ms Melanie Williams PhD studentDescribe your job I research parasites that cause disease in humans. I try to understand how they invade our cells so we can find ways to prevent it.

If you werent doing your job, what would you be doing? When I was a child I wanted to be an astronaut or an explorer. Now I see that theres a common theme with research they all involve exploring the unknown.

Whats the smartest thing youve been told? My mum always told me that I could do anything in life that I wanted to and I believed her.

Best aspect of your job? The moment when I discover something new and it takes me one step closer to answering a question.

Worst aspect of your job? When experiments dont work and progress is slow.

Whats one thing most people would be surprised to know about you? Before I was a scientist I was a restaurant manager. A really good one!

Best things about living in Melbourne? Caf breakfasts on the weekend.

Your favourite overseas destination? I love going anywhere tropical. I think all future medical research institutes should be built in tropical climates and next to a beach.

Who do you most admire? Activist for girls rights to education, Malala Yousafzai.

What do you want to be remembered for? Something remarkable that I havent done yet.

Professor Andrew Roberts was one of four institute scientists elected as fellows of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences.

Four institute scientists have been elected as fellows of the newly established Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences.

Institute clinician-scientists Professor Andrew Roberts, Professor Len Harrison and Professor Geoff Lindeman, and institute director Professor Doug Hilton, were among 116 eminent Australians appointed as inaugural fellows of the academy.

Australian Minister for Health, the Hon Sussan Ley MP, launched the academy in March in Canberra. Fellows were elected in recognition of their excellence and leadership in health and medical research.

Enabling clinical translationProfessor Andrew Roberts is head of the

institutes Clinical Translation Centre and is leading world-first clinical trials of new anti-cancer agents to treat blood cancers such as leukaemia.

Professor Roberts said the academy had identified mentoring the next generation of clinician-scientists as a priority. This has the potential to provide an enormous boost to Australias translational research capacity, ensuring our brightest clinicians can combine clinical and research careers to improve healthcare, he said.

Celebrating leadership inscience

Professor Hiltons research into blood cell development and function has provided new insights into how cells communicate in health and disease. As director of the institute and president of the Association of Australian Medical Research Institutes (AAMRI) he has championed improvements in government support of health and medical research.

Professor Len Harrisons election to the academy recognises his role in leading translational diabetes research aimed at preventing type 1 diabetes in at-risk people. Professor Geoff Lindeman is a breast cancer specialist whose research team was the first to identify breast stem cells, from which normal and cancerous breast tissue can develop.

This has the potential to provide an enormous boost to Australias translational

research capacity.

Four institute researchers elected to new science academy

S U P P O R T O U R R E S E A R C H w w w . w e h i . e d u . a uP a g e 4

Staff p

rofiles

-

Hepatitis B, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis are chronic infectious diseases, collectively responsible for the deaths of more than 3.5 million people each year.

In the case of people infected with hepatitis B, the infection will go largely unnoticed. Their immune system suppresses the virus and they dont display symptoms. Some are infected at birth or during childhood, and may not even know they carry the virus.

But for some, the virus continues to silently cause damage. Abdominal pain could trigger a visit to a doctor, where scans might reveal the previously unseen impact of the virus: cirrhosis (scarring) of the liver or, worse, liver cancer.

There is no cure for the two billion people living with hepatitis B and, though there is an effective vaccine, it can only prevent not cure infection. Current drugs prevent the virus from multiplying but do not eliminate it.

The story for people infected with HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other chronic infectious diseases is much the same. Is the approach of targeting the virus the best strategy to tackle infectious diseases, or is there a better way?

Kill the cell, kill the virusDr Marc Pellegrini joined the institute as a PhD

student in 2000 to work with scientists who were undertaking innovative research into cell signalling and cell death (apoptosis).

Their vision was to exploit the signals that trigger apoptosis as a way of treating cancer, he said. I wanted to know if we could use this same technique to cure infectious diseases by killing the cells they call home.

After 15 years of research, Dr Pellegrini and his colleagues have found a strategy that might prove to be the first effective cure for hepatitis B.

Our team has painstakingly analysed the hepatitis B virus to find out exactly how it prevents its host cell from dying, Dr Pellegrini said. We discovered that the hepatitis B virus alters signalling inside liver cells so that they are more sensitive to the molecular messages that tell the cell not to die.

Dr Pellegrinis team found that blocking a protein that prevents apoptosis could flip the signals in the cell so that, instead of preventing apoptosis, it was triggered and the infected liver cell died.

Excitingly, a drug had already been developed that targeted this protein, and was in clinical trials as an anti-cancer treatment, Dr Pellegrini said.

We demonstrated in our models that this same drug could have the potential to cure hepatitis B for the first time.

A new approachDr Pellegrini said many chronic infectious

diseases could not be cured effectively with current treatment strategies. Our current drugs for treating diseases such as hepatitis B, HIV and tuberculosis arent up to the task, he said.

Antiviral drugs suppress the virus but dont eliminate it. Tuberculosis can only be cured after a long and exhaustive course of antibiotics, and the number of cases of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is rising and is very concerning because there is very little we can do for thosepatients.

As a clinician treating infectious diseases, Dr Pellegrini could find common elements between different conditions. Human infections with HIV, hepatitis and tuberculosis all result from bacteria or viruses invading and living within a human cell, he said. Targeting the cells that host the infection could hold the key to beating these diseases.

Attacking the homeControlling cell death could potentially be used

to treat other chronic infections that promote the survival of infected cells, including HIV and tuberculosis, Dr Pellegrini said.

If the treatment strategy we are using to cure hepatitis B is shown to work in humans, it could potentially work against any virus or bacteria that invades and lives within cells in our body, he said.

We have great hope that this strategy for tackling infectious diseases will be successful. Targeting the host cell means the virus or bacteria cannot develop resistance, and gives us a real opportunity to win the fight against chronic infectious diseases once and for all.

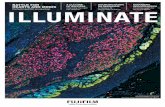

Institute scientists are searching for new ways to tackle infectious diseases by triggering infected cells (green) to die without affecting healthy cells. (animation: WEHI.TV)

Dr Marc Pellegrini

Dying to surviveCould a cure for hepatitis, HIV and tuberculosis be found by controlling cell death?

We have great hope that this strategy for tackling infectious diseases will be successful.

Targeting the cells that host the infection could hold the key to

beating these diseases.

S U P P O R T O U R R E S E A R C H w w w . w e h i . e d u . a u P a g e 5

Rese

arch

new

s

-

Gene architects guide embryo developmentInstitute researchers have identified two key proteins that act as genetic

architects, creating the blueprint needed by embryos during the earliest stages of their development.

Previous work by the research team showed that the protein MOZ relayed external messages to the developing embryo, revealing a mechanism for how the environment could affect development in very early pregnancy.

Dr Bilal Sheikh, Associate Professor Tim Thomas, Associate Professor Anne Voss and colleagues have now discovered that MOZ and the protein BMI1 play opposing roles in giving developing embryos the set of instructions needed

to ensure that body segments including the spine, nerves and blood vessels develop correctly and in the right place.

Reading the blueprintAssociate Professor Voss said the study

revealed that the two proteins tightly regulated Hox gene expression in early embryonic development. When the embryo is still just a cluster of dividing cells, it must become organised so that the body tissues and organs develop correctly, with everything in its right place, Associate Professor Voss said.

We showed that the proteins MOZ and BMI1

were important for initiating activation of the Hox genes, providing the blueprint the developing organism needs for proper development.

Importantly, MOZ and BMI1 could provide a mechanism to transmit signals from the environment to the developing embryo, with potentially devastating consequences.

We know that Hox genes can be directly affected by too much vitamin A, which can cause severe deformities in the embryo, Associate Professor Voss said. Substances or environmental challenges that impact MOZ or BMI1 expression could affect when and where Hox genes are expressed, causing defects in the developing embryo.

Blocking key survival proteins is a promising tactic for treating cancer. However new research from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute suggests care should be taken as these proteins are also vital for emergency blood cell production.

Dr Alex Delbridge, Dr Stephanie Grabow and Professor Andreas Strasser discovered that blood cell production after massive blood cell loss was fatally compromised when the cell survival protein MCL-1 was depleted.

Critical survival proteinDr Delbridge said MCL-1 was critical for the

survival of many cancer cells, and was being investigated as an anti-cancer drug target. Our previous research has shown that targeting MCL-1 could be used with great success for treating certain blood cancers, he said.

However the new research found that MCL-1 also plays an important role in normal blood cell production. We have now shown that MCL-1 is critical for emergency recovery of the blood cell system after cancer therapy-induced blood cell loss, Dr Delbridge said.

Avoiding side-effectsThe team found that reducing MCL-1 levels

hindered recovery of the blood cell system after extensive destruction of mature blood cells, which is a common side effect of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

We found that reducing MCL-1 protein levels severely impaired recovery of the blood cell system following chemotherapy, Dr Delbridge said.

This exquisite dependency on MCL-1 for emergency blood cell production has important implications for potential cancer treatments involving MCL-1 inhibitors, and will aid the design of future clinical trials of these drugs.

Our findings suggest that MCL-1 inhibitors and chemotherapeutic drugs should not be used simultaneously, Dr Delbridge said.

Researchers have revealed the unique signature of critical antibody-producing immune cells, showing the cells come in a variety of flavours.

The research identified potential targets for treating diseases of antibody-producing cells, including cancers such as multiple myeloma, and immune disorders such as lupus and rheumatoidarthritis.

Immunity that lasts a lifetimeAntibody-producing cells, or plasma cells, are

specialised immune cells that produce large amounts of antibodies. Antibodies are vital for lifelong immunity to infection, such as after immunisation. Each plasma cell is capable of making one specific type of antibody against a specificdisease.

Plasma cells live in the bone marrow, where they account for only one in 1000 cells, but they are the cells that impart lifelong immunity.

Associate Professor Lynn Corcoran, Professor Stephen Nutt, Dr Wei Shi and colleagues used complex biological and mathematical techniques to map the transcriptome of plasma cells. The transcriptome reveals which genes are switched on and functioning in the cell.

Associate Professor Corcoran said the gene signature revealed that each plasma cell had its own flavour. We showed that each plasma cell has a unique pattern of activity mapped in its transcriptome, she said.

The pattern denotes its flavour, telling the story of how it was activated, where it lives in the body, and potentially what infections it fights. We were surprised to find a number of genes were active that hadnt previously been identified as important in immune cells.

This gives us a host of new genes to look at in search of potential therapeutic targets for cancers of plasma cells, such as myeloma, she said.

Professor Stephen Nutt, Dr Wei Shi and Associate Professor Lynn Corcoran (L-R)

Dr Alex Delbridge (L), Dr Stephanie Grabow and colleagues found a survival protein being targeted by anti-cancer drugs is critical for emergency blood cell production.

Reducing MCL-1 protein levels severely impaired recovery of

theblood cell system followingchemotherapy.

Immune cells come in a variety of flavours

Anti-cancer drug could affect emergency blood production

S U P P O R T O U R R E S E A R C H w w w . w e h i . e d u . a uP a g e 6

Research news

-

As the institute celebrates 100 years of discoveries for humanity, we have begun securing the best and brightest minds for the next 100 years of research.

Seven generous donors have so far contributed $5 million to establish 10 Centenary Fellowships.

Institute director Professor Doug Hilton said the fellowships would provide crucial support for young scientists.

Our hope is that we will be able to embark on the next 100 years of discoveries by supporting 100 young scientists through the early phase of their careers, Professor Hilton said.

Funding future discoveriesFour Centenary fellows have already been

appointed, thanks to donations from the Walter and Eliza Hall Trust, Dyson Bequest, L.E.W. Carty Charitable Fund and the Alfred Felton Bequest.

Over the coming months, a further six early-career scientists will receive fellowships with the generous support of CSL Ltd and institute board member Mrs Jane Hemstritch. The University of Melbourne has pledged to support two Mathison Centenary Fellowships to aid clinician-scientists, in honour of the institutes first director-designate, Dr Gordon Clunes Mackay Mathison.

Professor Hilton said the centenary gifts would aid discoveries to benefit people in Australia and across the world. It is thrilling for our early-career scientists to be able to get on with their research knowing they have the support of the community, he said.

Supporting the next generationSecuring grant funding is becoming harder for

early-career scientists, Professor Hilton said. In 2014, the success rate among scientists applying for government research grants fell to less than 15 per cent, the lowest since the turn of the century, he said.

Our early-career researchers, however talented, must compete against senior and established scientists for these limited resources, and their lack of track record in comparison is a significant barrier to success. By providing five years of funding through a Centenary Fellowship, we can give them the best chance of being competitive for grant funding.

The institute has set a target of creating 100 Centenary Fellowships over the next five years. If you would like to invest in the next generation of scientists and support a fellowship, contact the directors office on 03 9345 2552.

$40,000 for research into childhood coeliac diseaseCoeliac Victoria and Tasmania has donated $40,000 to the institute to support studies into the under-researched area of childhood coeliac disease.

The donation will support projects by Dr Jason Tye-Din and his team to improve diagnostics and treatments that would be effective for both children and adults with coeliac disease.

Coeliac disease is caused by an inappropriate immune response to gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, rye and oats. It affects 1 in 70 Australians, causing digestive symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain and diarrhoea, as well as fatigue, anaemia, and even an increased risk of cancer. The only treatment currently available is a lifelong gluten-free diet.

Improving patient outcomesDr Jason Tye-Din said the funding would

support several projects.

Coeliac disease remains highly under-diagnosed and poorly managed, Dr Tye-Din said.

Among our current projects are studies to better understand how gluten affects children with coeliac disease, which can be quite different to adult disease. We are also establishing the mechanism for why symptoms occur, so the disabling symptoms caused by gluten can be better managed.

Mrs Jane Davies, executive officer at Coeliac Victoria and Tasmania, said Dr Tye-Din had been an outstanding advocate for coeliac research in Australia. Jason is the chair of Coeliac Australias medical advisory committee and is actively engaged in medical and public education on coeliac disease, she said.

This donation, made possible through a bequest to Coeliac Victoria and Tasmania, enables us to actively contribute to research into coeliac disease and support new discoveries for people with coeliac disease, she said.

Centenary Fellowships: investing in the future of medical research

Inaugural Centenary fellows Dr Ian Majewski, Dr Leigh Coultas, Dr Tracy Putoczki and Dr Simon Willis (L-R).

Mrs Jane Davies (L) and Dr Jason Tye-Din

It is thrilling for our early-career scientists to be able to get on with their research knowing they have the support of the community.

S U P P O R T O U R R E S E A R C H w w w . w e h i . e d u . a u P a g e 7

Sup

port

er n

ews

-

Produced by the institutes Communications and Marketing team. If you would prefer to receive this publication via email or have any feedback, please contact: Mail 1G Royal Pde Parkville Australia 3052 | Email [email protected] | Telephone +61 3 9345 2555 | Printed on 100% recycled paper.

Our centenary year is in full swing and we have many exciting events planned for the coming months to mark this momentous occasion. Join us at public talks, discovery tours and the Science in theSquare festival to commemorate our centenary.Since February, we have hosted a number of events to celebrate 100 years of the institute. Wehave welcomed more than a thousand dignitaries, alumni, collaborators, staff and students tothe institute. Take a look at our centenary year so far.

A sweet yearWhat is a birthday without a cake? On 10 and

11 March we kicked off our centenary celebrations with our staff, students, alumni and supporters, with a spectacular cake as the centrepiece of the celebrations.

Lighting up medical research

Our Parkville building lit up on 12 March when the Prime Minister of Australia, the Hon Tony Abbott MP, officially launched our centenary and illuminated the LED light curtain. A 1914 Rolls Royce that was owned by Eliza Hall and ordered by Walter Hall before his death in 1911 also made a special appearance.

Commemorating our inauguraldirector

When the agreement was struck to establish the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute on 23 April 1915, brilliant Australian clinician and researcher Dr Gordon Clunes Mackay Mathison was chosen to be the founding director. Dr Mathison was serving in Gallipoli where he was tragically wounded. He died 10 days later on 18 May 1915, before he knew about the position waiting for him inAustralia.

On 18 May the institute unveiled a sculpture honouring Dr Gordon Clunes Mackay Mathison, marking the 100th anniversary of his death. Created by master sculptor Michael Meszaros, the sculpture was commissioned by the Dyson Bequest and generously donated to theinstitute.

Lighting up our centenary

Walter and Elizas Big Night Out 15 August 2015An entertaining and curious journey through science highlighting 100 years of Australian medical research. Join host Paul McDermott (Good News Week, Doug Anthony All-Stars), science rock band Ologism and a panel of comedians for a night of trivia, theatre, music and laughs.Licensed event, 18+ only. Tickets on sale in early July at www.wehi.edu.au/centenary.

(Clockwise from top) Our building illumination; a birthday cake fit for a centenary; Prime Minister Tony Abbott speaking at the centenary launch; the sculpture dedicated to Dr Gordon Clunes Mackay Mathison.

Silver Screen Science 20-22 August 2015Hollywood loves a good science fiction film, but where are the facts among the fiction?

Watch feature films including Gattaca, Outbreak and Contagion before hearing from a panel of experts as they attempt to separate the possible from the just plain ridiculous. Free event. Registration opens in early July at www.wehi.edu.au/centenary. M15+

Art of Science exhibition 4-17 August 2015This free public exhibition will share scientific discoveries from an artistic perspective, showcasing finalists of the institutes annual

Artof Science competition.

Free event.

Talking Science: When will there be a cure for cancer?19 August 2015Hear from Melbournes cancer experts and discuss whether there will ever be a cure for cancer at this free public forum with an extended Q&A session. Free event. Registration opens in early July at www.wehi.edu.au/centenary.

To find out more about institute events, including public lectures and discovery tours, please phone 03 9345 2555 or visit

www.wehi.edu.au/events

4-22 AugustFed Square, Melbourne

S U P P O R T O U R R E S E A R C H w w w . w e h i . e d u . a uP a g e 8

Coming events

-

Support our discoveries donate today

The Walter and Eliza Hall Institutes researchers are working to understand, prevent and treat diseases including blood, breast, ovarian, bowel and lung cancers, type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, coeliac disease and malaria.We are doing this because: One in eight Australian women will be diagnosed with

breast cancer by the age of 85. Malaria kills up to 700,000 people each year. More than 120,000 Australians have type1diabetes. As many as 1 in 60 Australians havecoeliac disease. More than 100 clinical trials based on discoveries made at the institute are underway, including a new class of anti-cancer drugs and vaccines for type 1 diabetes, coeliac disease andmalaria.

The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute relies on donations from the community to continue its vital research. Donations of $2 or more are tax deductible in Australia.

w w w . w e h i . e d u . a u

-

$100

$

250

$50

0 $1

000

$25

00

My c

hoic

e $ ..

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

..

Che

que

(mad

e pay

able

to T

he W

alter

and

Eliz

a Hall

Inst

itute

of M

edica

l Res

earc

h)

Vis

a M

aste

rCar

d D

iner

s A

mer

ican

Exp

ress

Card

No

Exp

iry

date

/

Card

hold

er n

ame .

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

.. Car

dhol

der s

igna

ture

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

.....

Title

......

......

......

.....

Firs

t nam

e ...

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

.. La

st n

ame

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

.

Addr

ess

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

.....

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

.Sta

te ..

......

......

......

..Po

stco

de ..

......

......

......

......

.

Phon

e ....

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

...M

obile

.....

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

.

Emai

l .....

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

......

...

Your

supp

ort h

elps

us

impr

ove

lives

M

ailin

g ad

dres

s for

all d

onat

ions

:W

alte

r and

Eliz

a Ha

ll Ins

titut

e

of M

edic

al R

esea

rch

Rep

ly P

aid

8476

0 (n

o st

amp

requ

ired)

P

arkv

ille

Vic

305

2

To m

ake

a se

cure

onl

ine

dona

tion

visit

w

ww.

weh

i.edu

.au/

dona

teAl

tern

ative

ly, yo

u ca

n m

ake

a do

natio

n or

di

scus

s how

you

can

beco

me

invol

ved

by c

allin

g th

e in

stitu

te o

n 03

934

5 255

5.

The

inst

itute

pro

tect

s you

r priv

acy i

n ac

cord

ance

wi

th th

e In

form

atio

n Pr

ivacy

Prin

cipl

es o

f the

In

form

atio

n P

rivac

y A

ct 2

000.

The

inst

itute

s

priva

cy p

olic

y is a

vaila

ble

at w

ww.

wehi

.edu

.au.

Plea

se se

nd m

e the

in

stitu

tes

new

slet

ter b

y m

ail

or e

mail

I

would

like t

o jo

in a

disc

over

y tou

r to

see

labo

rato

ries

ina

ctio

n

Plea

se se

nd m

e inf

orm

atio

n on

mak

ing a

gift

to th

e ins

titut

e in m

y will

I ha

ve m

ade a

gift

to th

e ins

titut

e in m

y will

I wo

uld lik

e my d

onat

ion

to re

main

anon

ymou

s

The W

alter

and

Eliz

a Hall

Inst

itute

of

Med

ical R

esea

rch

ABN

12 0

04 25

1 423

Ple

ase

acce

pt m

y do

natio

n of

Illuminate June 2015

w w w . w e h i . e d u . a u