ill - NAU jan.ucc.nau.edu web serverjan.ucc.nau.edu/~rtt/pdf format pubs/Trotter 2000 pdf...

Transcript of ill - NAU jan.ucc.nau.edu web serverjan.ucc.nau.edu/~rtt/pdf format pubs/Trotter 2000 pdf...

I

ill

ROBERTA D. BAER, SUSAN C. WELLER, JAVIER GARCIA DE ALBA GARCIA,

MARK GLAZER, ROBERT TROTTER, LEE PACHTER, AND ROBERT E. KLEIN

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF THE FOLKILLNESS NERVIOS

ABSTRACT. To systematically study and document regional variations in descriptions ofnervios, we undertook a multisite comparative study of the illness among Puerto Ricans,Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Guatemalans. We also conducted a parallel study onsusto (Weller et al. 2002, CUlture, Medicine and Psychiatry 26(4): 449-472), which allowsfor a systematic comparison of these illnesses across sites. The focus of this paper isinter- and intracultural variations in descriptions in four Latino populations of the causes,symptoms, and treatments of nervios, as well as similarities and differences between nerviosand susto in these same commulrities. We found agreement among all four samples on a coredescription of nervios, as well as some overlap in aspects of nervios and susto. However,nervios is a much broader illness, related more to continual stresses. In contrast, susto seemsto be related to a single stressful event.

KEYWORDS: Latino folk illnesses, nervios, susto

~

INTRODUCTION

~I

Altliough there have been detailed descriptions of nervios from case reports andfrom specific regions, few attempts have been made to compare descriptions ofthe illness across cultures. Nervios is often glossed as "nervousness" or "anxiety"(Trotter 1982), althOUgh~t is not synonymous with formal definitions of anxiety,nor is it generally recognized by bio~edical practitioners. Low (1985) attempted tocompare published descriptions of nervios in di,fferent populations, but found thatmethodological differences in how individual studies were conducted made gen-eralizations difficult. She suggested. however, that the similarity between nerviosand susto (a folk illness glossed as frigbt or shock) might mean that they wereboth expressions of distress, but labeled differently by different segments of thepopulation. As such. unresolved issues include whether the term nervios meansthe same thing in different cultural contexts, and the extent to which nervios and

susto represent similar or distinct illness entities.Not simply part of the exotica of different cultures, folk illnesses have been

linked to morbidity and mortality. Susto is associated with an increased risk of co-morbidities and a higher mortality rate (Baer and Bustillo 1993; Baer and Penzell1993; Rubel et al. 1984) and nervios is now noted in the DSM-IV (AmericanPsychiatric Association 1994: Appendix 1). The study of these folk illnesses inrelation to physiological symptoms has not been for the purpose of reducing the

Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 27: 315-337, 2003.

@ 2003 Kluwer Academic Publishers.

316 ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

folk illnesses to their biomedical equivalents, but rather to understand the meaningof these ethnomedical diagnoses for increasing risk of morbidity andmortaIiiy.Since susto has been linked with increased morbidity (Baer and Penzell1993) and

mortality (Rubel et al. 1984), if nervios and susto are really just different ngmesfor the same problem, nervios sufferers may similarly be at increased health risk.

This paper explores inter- and intracultural variations in descriptions of thefolk illness nervios. Four diverse Latino populations are studied: Puerto Ricansin Hartford Connecticut, Mexican Americans in South Texas, Mexicans in

Guadalajara, Mexico, and Guatemalans in rural Guatemala. Since a first step is tounderstand an illness in its cultural context (Guarnaccia and RogIer 1999:1322)and then analyze its relationship to co-morbidity, this study first describes nervioswithin each of the fQur populations. One aim is to see if there is a distinct descriptionof nervios that is shared by culture members-a community explanatory modelof the causes, symptoms, and treatments for nervios. A second aim is to compare

descriptions across the four diverse sites to see the extent to which de;scriptions aresimilar and different in different cultural contexts. Finally, we compare detailedfindings for nervios with those for susto in order to determine if these two folkillnesses are synonymous or distinct.

BACKGROUND

One problem in our understanding of nervios is that studies have used a varietyof terms for the problem, including "nerves" (Finkler 1989; Krieger 1989; Sluka

1989), "nervousness" (Camino 1989; Koss-Chioino 1989), and "nervios" (Barnett1989; Finerman 1989; Kay and Portillo 1989; Low 1989). The literature indicatesthat the label "nervios" covers a broad range of problems in the mental health

realm, from depression to schizophrenia (Jenkins 1988). In some cultures, the termnervios may be preferred over the term "mental illness," and may be interpretedmuch more broadly (Baer 1996). The similarity between nervios and susto suggeststhat they may both be expressions of distress or stress, but the two different labelsmay be used in different contexts (Low 1989).

Nervios has been studied in a variety of locations (including Latin America, theMediterranean, northern Europe, and the United States) (Davis and Low 1989).But among some cultural groups, scholarship about nervios is less well developedthan for many of the other folk illnesses. This is particularly true for Mexicanand Mexican American populations (Trotter 1982). This pattern is curious, in thatTrotter (1982) found that in the lower Rio Grande Valley, nervios was the thirdmost frequent ailment reported (stomach ache and cough were first and second),and the most frequent folk illness.

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF ]HE FOLK ll.LIirnss NERVIOS 317

The folk illness nervios is so widely reported across many contrasting regional,linguistic, and demographic barriers that it defies description as a "culture-bound

syndrome" (Guarnaccia 1993). Nervios is consistently. described as a culturallyapproved reaction to overwhelmingly stressful experiences, especially concerninggrief, threat, and family conflict. However, it has been suggested that the waythe illness is experienced and conceptualized may vary across cultural groups

(Guarnaccia 1993).Guarnaccia et al' (2003) have found that Puerto Ricans differentiate between

categories and experiences of nervios. SeT nervioso (being a nervous person) isa result of traumatic experiences of suffering, and usually begins in childhood;

the condition lasts the rest of the person's life and results in more life problems~Symptoms include unusual amounts of crying, headaches, stomach aches, andincreased anger and violence, particularly in men. Herbal teas and the help offamily members, priests and ministers, and psychologists and psychiatrists werethe recommended treatments. Padecer de [os nervios (suffering from nerves) ismore of an illness, and is associated with depression, although the body is alsoaffected. Life problems, including marital difficulties, are seen as the cause, and itusually develops in adulthood. This condition is considered to bea form of mentalillness, and the help of physicians, psychologists and psychiatrists is recommended.Ataques de nervios {nervous attacks) occur as the result of a stressful event, oftenin the family setting. Those who are nervous or suffer from nerves are more likelyto suffer from nervous attacks. Due to an event such as the news of the death of afamily member, the person becomes hysterical and "out of control" (Guarnacciaet al. 2003). This problem is more common in women, although it can occur inmen as well.

In Guatemala, nervios is conceived of and treated as an illness rather than asymptom, and, according to Low, "is associated with experiencing strong emo-tions, particularly anger and grief or sorrow, and with problems related to repro-duction and child rearing" (Low 1989:24). Women are significantly more likely toreport nervios than men, which suggests tllat the illness is related to gender-basedconcerns in general, and socially manifested expressions of strong emotions inparticular (Low 1989:24). There is also an ethnic dimension in the recognitionand reporting of nervios; most studies have focused on nonindigenous Spanish-speaking populations (ladinos). Causality of nervios is attributed to anger, grief,birth control pills, other illnesses, the birth of a child, anxiety, problems, susto, andother stressful occurrences (LQW 1989:31). Reported symptoms include headaches,despair, facial pain, trembling, and anger (Low 1989:29). Treatment most com-monly comes in the form of "nerve pills" bought in local stores or alternative homeremedies (Low 1989: 24). Further, Low suggested that nervios might be the termused by more urban/ladino populations for what rural/indigenous people call susto

318 ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

-r:';"

(Low 1985) and may reaffinn an "urban, upwardly mobile Ladino identity" (Low

1989:133).In Mexico, as in Guatemala, there is a higher prevalence of nervios among fe-

males; this is attributed to their inferior social position (Finkler 1991:43). Thisis further illu~trated by reports that nervios is associ~ted with stressed, harassed,

abused, and/or neglected women in rural Mexico (Davis and Low 1989; Salgadode Snyder et al. 2000). In Mexican populations, nervios is simultaneously an ex-planation of illness, a symptom of illness, and a state of illness. However, thosesuffering from the symptoms of nervios report a wide variety of symptoms, in-cluding feelings of desperation, headaches, chest pains, abdominal pains, high andlow blood pressure, and various familial, social, political, and economic concerns

(Finkler 1989; Salgado de Snyder et al. 2000). Patterns of treatment in Mexico in-clude home remedies, especially herbal teas, frequently used in combination with

physician-prescribed medications (Finkler 1989).Among Mexican Americans, Jenkins (1988) found that the tenn nervios is used

to cover everyday problems causing distress, serious family conflict, as well asschizophrenia. Symptoms associated with nervios included irritability, hopeless-ness, nervousness, depression, physical effects, and difficulty in functioning insocial or occupational roles. For Mexican and Mexican American farm workers inFlorida, nervios was the label that covered many conditions considered biomedi-cally to be mental illnesses. However, nervios was not considered to be a mentalillness by the farm worker~ (Baer 1996). Causes of nervios included money, foodand work problems, and accidents; treatments suggested were talking to some-one about the problems or getting medical or psychiatric help. Among MexicanAmericans, nervios has been reported as being more common in women (Jenkins1988). In a study qf widows, Kay and Portillo (1989) found that the more bi-cultural a woman was, the less she was troubled by nervios. Both somatic andnonsomatic symptoms were reported, but it was primarily the nonsomatic symp-toms (fear, worry, anguish, anger, separation sorrow, loneliness, disorientation,_,feeling empty, confusion, and a feeling of being in the way) that distinguishednervios.

Although these findings suggest similarities among these populations in theirdefinitions of nervios, each study used a somewhat different approach and re-search instrument that limits our ability to tell how similar nervios is amongdiverse Latino populations. To systematically study and document regional vari-ations in descriptions of nervios, we undertook a multisite comparative study ofnervios. Using four distinct geographic and cultural locations, we examined de-scriptions of nervios to see the degree to which individuals within a communityreported similar causes, symptoms, and treatments for nervios, and then compareddescriptions across sites. We also conducted a parallel study on susto (Weller

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF THE FOLK ILLNESS NERVIOS 319

et at. 2002), which allowed for a systematic comparison of these illnesses acrosssites.

MElliODS

Data collection

Four Latino populations were sampled. In the United States, people were i.nter-viewed in the Mexican American community ofEdinburg, Texas, and the mainlandPuerto Rican community in Hartford, Connecticut. The other two research loca-tions were the rural ladino community of Esquintla, Guatemala, and the urbanMexican community of Guadalajara.

The Mexican American interviews were conducted in the lower Rio Grande

Valley community ofEdinburg, Texas. This region is among the poorest metropoli-tan areas in the United States. Located 15 miles from the US-Mexico border, the

area, although a mixture of urban and rural, is predominantly agricultural. Thepopulation is 80% Mexican American. Hartford, Connecticut, is a medium-sizedcity in the northeast United States. While only about one-third of the city's pop-ulation is Hispanic, children of Puerto Rican descent make up 47% of those inthe public school system. The interviews for this study were conducted in thetwo census tracts that have the majority of the Puerto Rican population. TheGuatemalan interviews were conducted in the department of Esquintla, locatedon the Pacific coast. This area is agricultural; primarily cotton and sugar caneare grown. The population sample was Spanish-speaking ladinos in four rural

villages, each of which had a population of about five hundred. The Mexicansample was drawn from the modern industrial city Guadalajara, which has apopulation of approximately three million. Predominantly mestizo, residents ofGuadalajara are from both rural and urban backgrounds. In order to capture thevariation present in the city, three neighborhoods were sampled, one middle class,one working class, and one poor; all of those interviewed were Spanish-speaking

mestizos.To ensure representative samples in each community, a two-stage random sam-

pling design was employed. First, a village, neighborhood, or census tract waschosen, and then blocks and households were selected. The inclusion criteria werethat the respondent be an adult and recognize nervios as an illness entity (respon-dents were asked simply if they 'had heard of nervios'). Additionally, in Edinburg,respondents had to self-identify as being of Mexican descent, and in Connecticutthey had to self-identify as being of Puerto Rican descent. The preferred respon-dent in each household was the female head of household, since we assumed'that women have more responsibility for health. Interviews were conducted by

320 ROBERTA D. BAERET AL.

bilingual research assistants in the language preferred by the interviewee (English,Spanish, or a combination).

Questionnaire development

Ten to twenty initial key infonnant interviews at each of the four Latino siteswere used to develop the questionnaire. We focused on the tenn nervios, whichis recognized in all of the cultures studied, as opposed to the more extensive

variants of the condition seen among Puerto Ricans (Guarnaccia et al. 2003). Using

open-ended interviews and free listing techniques (Weller and Romney 1988),qualitative data were gathered on the explanatory model of nervios, including

perceived causes, symptoms, and treatments of nervios (Table I).In Mexico, respondents were also asked about similarities and differences be-

tween nervios and susto. On the basis of the open-ended interviews (any responsementioned by at least 10% of the sample), symptoms from the Cornell MedicalIndex, and the anthropological literature, a true-false questionnaire was developed.The final questionnaire I contained 125 items addressing the causes, symptoms,

and treatments for nervios. The questionnaire also included basic demographicdata on the respondent, as well as questions about experiences with nervios. Fi-nally the questionnaire was translated into the fonn of Spanish (or English) spokenat each particular site being studied.

Data analysis

Our goal was to determine the descriptions of nervios in the four Latino groupsas well as the degree of similarity and difference among the groups. This wasaccomplished with a type of data analysis called consensus analysis. Given a set ofrelated, closed-ended questions, a consensus analysis accomplishes three things.First, it provides an assessment of the agreement among respondents to see ifthere is sufficient agreement to warrant aggregating responses. Then, if there issufficient agreement, it provides estimates of how well each person's responsescorrespond to the "group ideas." Third, it provides estimates of the answers to theset of questions.

A consensus analysis is an analytic tool that allows one to determine whetherthere is group agreement--or consensus-in responses to structured questions.Identifying or creating a reliable description of community explanatory modelsincludes an assessment of variability of ideas. If variability is high-that is, ifrespondents do not agree with one another and do not seem to have similar ideas-then it does not make sense nor is it accurate to create a unitary, simple aggrega-tion of responses. If, however, informants report similar or identical information,then one is justified in pooling the information to create an overall description of

-.,~ "E~ Q)~ z

A CROSS

OJ:c'ROJu'"~

rI)

,~0

~

~~u

e~~r'1

'"cOJe'iUeF"'

6'N

II.::.-'"'(U

~~::sO.'!J '"tU'3"'~] ~ :8 0;'::soF'C~~-\ONI1J

'"0

'0

tIS ~ "2N- '"G)G) 0~=tIS- §u e a c "-G)O)u5 ~'O'OG)'" c 'O.£",c~&

oo ootlS.c",--0 e "= u e G)00- oC '"Q Q ,Q. Q C "C "~ ,9<-o ~~F-' --OO\C~,,",NN

TO nIB STUDY OF nIB FOLK ll..LNESS NERVIOS 321

'2=00) .-

-u'" = 0

~ ~£ ~ ~.~ Q, =:a 0) 0):= ~.g= 'Q",,!!;.-8 '" = 0 == = u 8 .-:=-- 0

~ S u .c: .-'" = .-0 ',;3 '" ~= 0 0» -00-8 0) 'Q "'=-~~ u 0)= -0) """'Q"'.~=8-== ".00.-

"8 .0' ~ ~ S 0) .-U ="=O)=:(U=~"'=Q,O)Q,u...£t:S= 'v ..,.0000000_0-~~~~~~~~

'0'0\1")"""",('1('1('1

'0---oUB oU~C g ee ,cO)-oU'E~ ':0)., 0) oU~ u-

~~ oU ~se-c C oU'- ...~ 0Oc U 0) 0)oU .-'C oU oU ...oU ~ ::s '0 Q.

.s !:! 'C S e .9 ~ '0 ~ e g eoU~Q.~~uu~~O)Q.O)U c~ oU~~,~~O~ 0) 0)

.., Q ~~

--.tNN-OO\O-.tN-NN

"'Q)

:aQ) -Q) e 'E"' ~Q) Q)

Lii '" 5 ~~Q)ou:E'"ia§g~i:;.U:I:O",,~~0\r-.10~

,-.. '" '"0 ., VN'::: '" ~.&} OS 0II .-~.-'" 0 ur:fi... ~ ~'-""£ osV"Ol:3o",u "'POos",u OS OS os "0 .-.- e ~ u V V "0>< V"O ~

~ is ~ "0 &. ~ .~~ "0 '" .-'" '".v '" os-os to

e 00 ~ 0 .-e 0 = =to OS "0 0 0.= -= .-"3 0 0 '" '"os""~-= 3 -""" ~ ~V.- vv

"Ooo<z <~~§-V)V)VNNNM~

~° ~

:~ o.=-~ == °~ uou °~'8Poou;ou .~ 0)Po-~~ ~~ou

~ .sPoPo.-= ; ou~ == ou-~~ ~ ~~.s0... ~ 0. ;.-0) >U '" O~O)OU OU OU="'-Po e ~ O- ~ ~ -

= O)O)UO)l:I>-g .9 :E O(;' ~ U ", ",0)"' ° ...",0).-0...=...OO»"O:~

g..cng..U:%:<l:OU.=~~\O,,",NN

0-05 -.-=e .~~ ebO .-~ 0 g

N -a==.2, ",00= ~ -0 '" .-

00 '" ="'~-0 .~ "'"' 0 -0 =' ~ '" ~ -0 .-~ ~.~ '" 0 oJ:: '" -0 -S !§"~ g .E .os ~ :a ~

u ~ "' ~ 0 .;: 5 t "'

ONZ~~C:>CI)~~-""""~~~NNN

0/)c'l:J

E;;'~0 t:~ G);,; ~., ..

~~=.,boG)..C PoCoj.,00/)-"- C .-., >C "l:J G)

~ 'Q) Cr-.~<-N-

e...Q)0"0-Cue -0 =' '"

"Ou~0 ..-0 ><0 -(1j

0 -Q""Q)_o~-r--r--

~.~

>,i1

S'~= -, 5

::i;. .~"O.-~'" '" -~ -~",",0

~~:uE -bO ~ ~§ .-'" .-.c

.-'""0 0 2.E"' e ."' bO

~ ~.S~~N""~-r-1r)

6' ~N '"

Q)

II .s ~~ -Q)'-" 0 aII) ."'" C 0~ =.Q

~Q)~~.§ ~ ~

~>->-'"::s COO.g<-~~OOIn~

-~~ ~

~ ~

~!

322

'"c

~~

~au

~is.e;.,

C/)

Q)

;§~u'"=

(/)

.~0

~

~~~=0u

~~0

i0)

"Q.~~("I

~.~ ~N ...C >, U~ t:l. 0e ~ "0'-'~ e~-'" 0O)";J .t::'"-00 CO)~ CON

.p ;:=...;) 0) ~ .-0) '" '" u ='

'-=C =' ~ C" .=' '" u C~ 0:::: 0 ~

~U~Z~~on~~('1('1N

/)Q

.5

'] Q)...

Q) Q)

-oS~ '0

~ oS ~~ e Q)~ 0 !U ~Q)Q) '" u ~n""...:::: ~ ~ -.;:Q.:a=' oS ~8.'" u" '" .Q Q.8 .-£ Q. /)Q .Q ~ ~:c ~ e 8 .5 '" ~ ~ ~.Q~8.-;noS~e"'~"2/)Q tU '" Q) '" 0 '" = ..

::E~~~~~c/).3~~-q-C'")MNMMNNNN

ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

'" '"~ e.-v--

0.-0V -5 P.

=.s:.,-. .--0 .--'" ~II ~ 8-~ '" 0

'-' ,...u-0 0= u 0 v.;j --=

u cu.oV

V .s:.cue= ...== V .-= 00 = ~ V'~u~OV[a>-.o-a~'"S.o=0 ~ 0 .s:. .cd

.g<~~~~[aC'1N- -:I:

---s='" = 0Q) Q)o ~ e =' .-Q) Q)OO>-= 0.. .s ::::'" 0 e '". e .-Q) (UU= ..~ 8-0 ~ U '"

~ >-Q)",Q)'-' :a.E"'='CIo"'0 u~ij~~ .~] ~ ~ '"0 00 '" "'=' .~u .= ~ ~ ~.2 "'='~ -.Qu Q)0 000 00='" =_0=0'" Q) .-" .~ Q)j o..>--'" eu "'. 0 -

fJ)UZ~~Or'I- -'"---rn

rn SS .2Q) .g

.0 Co0Co Q) .~

-5~ -5.~ -5 Q)." .-~Q) " ...800 ~ rn-= -'"~Q)~ ,,~

o.c:~ Q»-Q).~ ~ ~ = -s:. -;n :c;g ~ rn .~ 0 g 8= 0 8 rn >- Q) 'c Co0 ., rn ...Co Q) .

00-Q)Q),:,d rnU = :c = rn rn0 Co ~ Q) 0 Q)

~~~~<~B~..., -

c0

p; ~tuOJ O).c0 Po~

"0 N>. O)~

.0 -50)"0 P; 0"00) OJ C~.0"'0 ~=

c"8 ~ "0 P; ~.9 '" ;.:= ~ bI) bI)~ 0).- 0 >. bI) c -,~ = Po C ~ -.~ Po 0" bI) ~.- ~"O",gc""~ C0) == ~ 'c ] ~ 0) .-=

~:C::E'"'~E'"'~r5Z:QMMM

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF THE FOLK ILLNESS NERVIOS 323

ideas in a group. Consistency among respondents' answers is indicative of shared

knowledge.Consensus analysis is conducted in a fashion somewhat analogous to factor

analysis. In factor analysis, the structure among a set of variables is described by

classifying items into groups or factors. A single factor solution indicates that allof the items are "related" in some underlying way. Consensus analysis can be con-

ceptually thought of as a factor analysis of individuals in a sample, much like howstandard factor analysis groups individual items in a questionnaire. A single fact(jrsolution indicates homogeneous responses among a single group of respondents,

i.e., consensus. In this study, consensus analysis is used to determine whether the

aggregate responses to the yes/no questions on the nervios questionnaire indicate

underlying group agreement (consensus) at each site and between sites regardingthe domain of study (nervios susceptibility, causes, symptoms, and treatments).

Consensus analysis also provides an estimate of each respondent's concordancevis-a.-vis the group (their cultural knowledge or "competency" score). The analysisalso provides a best estimate of the group's answers to the questionnaire items,using a Bayesian posterior probability approach wherein the responses of individ-uals are weighted based on their relative knowledge vis-a.-vis other respondents inthe group. In this study a conservative Bayesian classification rule was used. Itemswere classified at the p ~ 0.999 confidence level.

As with most sample size requirements, sample size determination is a functionof variability. In consensus analysis, the variation is the amount of agreement

among the respondents. For dichotomous response data, using a moderate level of

cottlpetency or agreement (0.50), a high confidence level for classifying items as"true" or "false" (0.999), and a high accuracy for questions to be correctly classified(0.95), a minimum number of 29 respondents per site are required (Romney et al.1986; Weller and Romney 1988). To be sure that we had sufficient individuals for

comparative purposes within samples, a sample size of about 40 was obtained ateach site.

RESULTS

The sample

The final sample consisted of 40 respondents in Connecticut, 41 in Texas, 38 in

Mexico, and 40 in Guatemala, Respondents were primarily women (100% in theMexican and Texas samples, 90% in Guatemala, and 87% in Connecticut). Allof the informants in the Mexican sample were born in Mexico, and all of the

informants in the Guatemalan sample were born in Guatemala. In the Connecticutsample, 90% were born in Puerto Rico; 70% of the interviews were conductedi~ Spanish, 3% in English, and 28% in combined English and Spanish. In the

324 ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

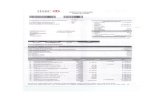

TABLE II

Sample Demographics

Guatemala Mexico Texas Connecticut

4090

42.9 (17-83)6.3 (0-14)5.4 (1-9)1.8 (0-9)

95%88%65%

38100

38.5 (20-85)4.4 (0-16)5.7 (I-Ii)5.5 (0-13)

82%74%63%

40100

42.2 (18-81)2.8 (1-7)3.8 (2-9)

11.2 (0-16)90%71%46%

4087

37.1 (20-58)2.8 (0-12)4.1 (1-8)

10.3 (0-15)90%80%52%

Sample size% femaleAge in years (range)Total children (range)Household size (range)Education in years (range)Knows someone with nerviosFamily member had nerviosRespondent had/has nervios

Texas sample, 95% of the respondents were born in the U.S., and 66% of theinterviews were in English, 7% in Spanish, and 27% in combined English and

Spanish. Respondents' educational levels varied significantly between samples,reflecting normative rates for each region: 1.8 years in Guatemala, 5.5 years inMexico, 11.2 years in Texas, and 10.3 years in Connecticut (Table II).

Actual experience with nervios varied somewhat by community. Most respon-dents knew someone with nervios (95% in Guatemala, 90% in Connecticut andTexas, and 82% in Mexico) and had experienced it in their family (88% Guatemala,80% Connecticut, 74% Mexico, and 71 % Texas). Of our respondents, about two-thirds of those in Guatemala and Mexico had experienced nervios themselves;46% of those in Texas and 52% of those in Connecticut also reported it.

Descriptions of nervios

Analysis of responses to the 125 items concerning the causes, symptoms, andtreatments for nervios revealed that a single, shared system of knowledge aboutnervios exists for each sample of respondents. The cultural consensus model fits theresponse data (the eigenvalue ratios all exceeded the recommended 3: 1 ratio: 9.85in Connecticut, 8.81 in Texas, 6.51 in Mexico, and 5.48 in Guatemala). Responseswere the most homogeneous in the Texas and Connecticut samples, resulting inthe highest levels of sharing (the average cultural knowledge scores were 0.73in Texas and 0.62 in Connecticut). The Mexican and Guatemalan samples alsoexhibited shared ideas, although at a somewhat lower level (0.?2 in Mexico and0.43 in Guatemala). Analysis with all four samples together indicated that theyshare a single description of nervios, with about 52% of ideas in common (culturalknowledge level = 0.52, eigenvalue ratio 6.45). A comparison of knowledge lev-

els across samples indicated that there was a greater degree of shared responsesin Texas than in Connecticut, significantly greater sharing in Connecticut than

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF THE FOLK ll..LNESS NERVIOS 325

Mexico, and significantly greater sharing in Mexico than Guatemala (ANOVA

p ~ 0.00005; Scheffe comparison p ~ 0.005).The distribution of cultural knowledge within each sample was more strongly

related to demographic characteristics than to personal experience. In Mexico,those with fewer children (r = -0.37, p = 0.02), fewer people in the household(r = -0.32, p = 0.05), and a higher educational level (r = +0.29, p = 0.09)

knew more about nervios. Similarly, in Texas, households with fewer people inthem were associated with greater knowledge about nervios (r = -0.42, p =

0.01). In Guatemala, a larger household was associated with more knowledge(r = +0.29, p = 0.07). Personal experience with nervios (knowing someone with

it or having had it) was associated with greater cultural knowledge, althoughthe associations were not significant. Greater cultural knowledge was corre-lated with knowing someone with nervios (r = +0.22, p = 0.18 in Texas, andr = +0.29, p = 0.07 in Guatemala) or with having had it (r = +0.24, p = 0.13

in Connecticut). Responses were not different (p > 0.05) between men and womenin the Guatemalan and Connecticut samples, nor were responses different by lan-

guage preference in the Texas and Connecticut samples.Although the four sites shared a common description of nervios, there was some

variability, as illustrated by a more detailed comparison between the samples. The

highest agreement occurred between the Connecticut and Texas samples with 78%identical answers, followed by 64% agreement between the Texas and Mexicansamples, and 57% agreement between the Mexican and Guatemalan samples.Tables ill-VI show the questions about nervios that were classified using consensusanalysis by one or more of the samples as having the answer "true" or "yes." Studysites are indicated with a "G" for Guatem~a, "M" for Mexico, "T" for Texas, or"C" for Connecticut. Item classification is indicated with a "Y" for "yes" or "true,"an "N" for "no" or "false," and a hyphen ("-") to indicate that the item could notbe classified as either true or false. We first discuss the findings for nervios andthen compare the findings with those for susto.

For susceptibility (Table ill, columns 4-7), there was agreement among at leastthree of the samples on 10 of the 14 questions (71 %), and among all four sampleson 6 of those questions (43%). Nervios is seen in adults and older people, andthough it can occur in anyone, it is more common in sensitive people. The foursites also agreed that nervios is not a problem among men, and does not occur onlyin families who believe in it. Three of the sites also answered that nervios was seen

mainly in women, but also occurs in older children, people with low resistance,weak people and those of weak character.

For causes of nervios (Table IV, columns 4-7), at least three samples agreed on27 out of 31 (87%) of the questions, and all four s3:ffiples agreed on 14 of those

questions (45%). All four samples reported that not eating well, drinking too much,and using drugs can cause nervios. In addition, a fright (susto) or shock (seeing

326 ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

TABLE ill

Susceptibility

Susto NerviosGMT GMTC !

,

\1Iif

yy

yNN

YYY

YYN

yyyyNN

y

yyyNyN

Y

~If,II

Adults get itOld people get itAnyone. regardless of age and gender/sexMore in sensitive peopleMainly in menOnly in families who believe in it

Mainly in womenOlder childrenMainly in weak peopleMore in people with a weak characterPeople with low resistance

In young childrenIn unborn children, if their mother has itRelatives of someone with it more susceptible

A baby if breast feeding from a mother who has it

~

someone get killed or being in an accident) can cause nervios. Also important incausality are strong emotions, anger, worry, family problems, and family fighting.Nervios is not considered to be contagious. A relationship between susto andnervios is evident, as susto was considered to be a cause of nervios. In addition,several situations that are usually cited as producing susto-seeing someone killed,seeing or being in an accident, or a surprise or shock-were also considered tobe causes of nervios. While the four sites agreed that a cause of nervios mightbe not eating well (three sites also thought hunger could cause it), food stuck inthe stomach (usually associated with the folk illness empacho) was not consideredto be a cause of nervios. Three sites also agreed on a lack of hot/cold causalityof nervios. There was also agreement among three sites that witchcraft was not acause of nervios, but that the Devil might be.

For the symptoms of nervios (Table V, columns 4-7), there was agreement acrossat least three of the samples on 62% of $e questions (24 out of 39 questions), andamong all four of the sites on 44% (17 out of 39) of the questions. Symptomsagreed upon by all four sites included depression or sadness, a feeling of no hopein life, crying, hysterical crying or crying attacks, and shaking or trembliI;lg. Othersymptoms agreed upon by all four sites were headache, a feeling of choking, coldsweat, weight loss, bad temper, insomnia, and anger caused by small things. Therewas also agreement that runny nose, fever, slow healing wounds, and a swollenstomach were not symptoms of nervios. Additional symptoms agreed upon bythree of the sites included lack of appetite, agitation, and convulsions or seizures.

~

yyyyN

yyyy

yy

yyyyNN

NYNNN

YNN

yyyyNN

yyyyN

Ny

yyyyNN

NyNNyyNN

N

yyyyNN

yyyyyyyyN

'~::"C

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF THE FOLK ILLNESS NERVIOS 327

TABLE IVCauses

SustoGMT

NerviosGMTC

NNNN-NNYNYYYYYYYYYYYY-YN

yyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyYYYY

YYNY-YYYYYNYYYNYY-YNYNNNYNNNYNNNY-NN-YNNNNNN-NNN

NNNN

N-NNNNYYN--NN-NNNNNNNYNNNNN-YNNNNN-NNNN

From not eating wellFrom drinking too much alcohol

By using drugsNervios causes susto/fright or susto causes nervios

By seeing someone get killedBy seeing or being in an accidentBy a sudden surprise or shock

By fighting (between spouses or with children)By strong emotions (good or bad)From angerBy worrying a lotFrom family problems

From living in a dirty houseFrom hungerBy the devilFrom low resistanceBy a hard, envious stareFrom cold foods (or drinks)By getting wet when you are sweatingBy being exposed to drafts/wind/air

By parasitesBy spiritsFrom food stuck in the stomachBy witchcraftBy using the utensils of someone who has it

--For treatments (Table VI, columns 4-7), at least three of the samples agreed

on 73% (30 out of 41) of the questions, and all four samples agreed on 51 % (21{jut of 41) of the questions. For all four of the sites, over the counter remedies(such as aspirin, Vicks, cod liver oil, Alka Seltzer), antibiotics, and treatmentsused for other folk illnesses (such as barrida, or sweeping with herbs, rubbingwith an egg, a spoonful of oil, pulling the skin of the body until it pops, or bindingthe waist) were not indicated for use in the treatment of nervios, nor were theservices of the folk healers, curanderos, or spiritualists. Other treatments rejectedby all groups included spearmint tea, enemas, scaring the affected person, drinkingalcohol, warm towels on the body, and drinking milk. Sedatives, praying, andtrying to relax were the only suggested treatments agreed on by all four samples.Additionally, three of the sites recommended the use of physicians and psychiatristsor psychologists, and rejected the use of holy water sprinkled on the body in theshape of a cross, as well as the use of a pharmacist, herbalist, wise old woman, orgrandmother. Three sites reported that nervios would g{j away by itself.

328 ROBERTA D. BAER ET AI

TABLE V

Symptoms

SustoGMT

NerviosGMTC--

yyyyyyyyyyyy

Y-NN---YY

YYNYYNYYY

--NN-YN-YNYYNYYNNNYYY--NY-YYYN

-NN

N-YNNN

CryingHysterical crying or crying attacksDifficulty going to sleep and staying asleepFrequent shaking or temblingSadness (and depression)A feeling of no hope in lifeSmall things cause an"gerA bad temperA headacheA feeling of chokingA cold sweatWeight loss

A lack of appetite

AgitationA convulsion or seizure

Cloudy or blurred vision

Difficulty breathingStomach pain or stomachache

VomitingDiarrheaItchingPaleness

SleepinessChillsMuscle and body aches/painsLosing consciousness

Affected hearing (ringing or buzzing)Frequeru _urinationChest painAching teethFace pain

Differences between sites

TheI;e were, however, some interesting differences between the sites. OnlyGuatemalans reported eating cold foods or getting wet while sweating or drafts ascauses of nervios, and only they considered face pain to be a symptom and garlicto be a treatment. It would appear that as far as nervios causality is concerned,hot-cold explanations are more important in Guatemala than at the other sites. An-other distinctive pattern occurred in the Mexican and Guatemalan samples, whereuntreated nervios was reported to cause a person to become diabetic or the mouth

to become twisted and deformed.

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF M FOLK ILLNESS NERVIOS 329

TABLE VI

Treatments

SustoGMT

Nervios

GMTC

NYN-YYYYY

NYYNNN-YNNNNYYNY-NYN-

NYNYYN

yyyyyyyyyyyy-yyyy-yyyy-y-NNN-NNN-NNNNNNN

-YNYYYNNYYNN

N-NYY-NNYNNN-YNN-YN--YN-NNYNY-N-N-NN

NNN--NNNNN-NYYYYYNNNYYYNY-N

SedativesTrying to relax (keep calm)Praying

MassagesDoctorPsychiatrist or psychologistPharmacistHerbalistWise old woman/grandmotherCurandero

Tea of orange leaves or orange blossomIf not treated, person becomes diabeticIf not treated,mouth becomes deformed and twisted

Camomile teaVitaminsGarlicRubbing the back and chest with alcoholTreated at homeGo to churchGo away by itselfIf not treated, can one dieHoly water on body in shape of a cross

Comparisons with Susto

The next issue we address is that of similarities and_qifferences between nerviosand susto. We conducted another study similar to our investigations of nervios

exploring regional variations in beliefs about susto (Weller et al. 2002). The sustostudy was originally planned for the same four sites where nervios was studied;however susto was not found to exist as an illness among the Puerto Rican pop-ulation in Hartford, Connecticut. As a result, the discussion below compares theresults from the three sites that recognized both of these illnesses-Guatemala,Mexico, and Texas. The methodology used in both the susto and nervios studieswas the same; in fact, 85 of the questions used in the two studies were iden-tical. While the actual respondents for the nervios and susto studies were notidentical, each sample was representative of the community from which it wasdrawn.

Susceptibility is broader forsusto than for nervios (Table III). Younger and olderchildren can suffer from susto, but this is not the case for nervios which seems tobe more of an adult problem. Nervios is felt to occur mainly in women, while susto

330 ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

is not as closely linked to gender. While there is some overlap in causes of sustoand nervios (including seeing someone get killed, seeing or being in an accident,and a sudden surprise or shock), susto seems more related to a particular incidentor accident. In contrast, causes of nervios are of a continual nature in one's life,and include family problems and fighting, drugs, alcohol, worry, anger, and strong

emotions (Table IV). Note, however, that susto Gan cause nervios and that nervioscan cause susto.

A similar pattern is seen with regard to symptoms of nervios and susto, withoverlap in symptoms such as crying, shaking, and difficulty sleeping (Table V).However, there are many symptoms that are unique to each illpess. Paleness maybe more restricted to susto, while headache, a feeling of choking, cold sweat, and

weight loss are associated more with nervios. Neither illness seems to manifestsolely with somatic symptoms. While praying is recommended for both sustoand nervios, the most striking difference between the two illnesses is the useof Western versus folk treatments. While a doctor or psychologist or psychi-

atrist is recommended for nervios, they are not considered effective for susto(Table VI). In fact, home treatment and folk healers are used more often forsusto.

Patterns of regional variation similar to those found for nervios also appearfor similarities and differences between susto and nervios. Only the Mexican and

Guatemalan samples report that weak people ,and people with a weak characterare more likely to get either illness (the Texas sample did not) and that the Devilcould cause both susto and nervios. Similarly, these two sites saw diabetes as a

possible outcome of both untreated susto and untreated nervios. Guatemala wasthe only site to feel that drafts were a cause of these illnesses. Finally, only theTexas sample reported that both nervios and susto would go away by themselves.

We also compared the differences between nervios and susto which emergedfrom the analysis of the structured questionnaire data to those differences repOrtedin the initial open-ended interviews in Mexico. In those open-ended interviews,respondents were asked about the similarities and differences between nerviosand susto. We found that both sets of interviews contained similar themes: susto isconsidered to be briefer than nervios, and nervios is more chronic and is a continualstress. Susto is caused by an identifiable event-a "susto"-while nervios is caused

by persistent problems.In summary, there is an overlap in many aspects of these two illnesses. Both

tend to occur more in adults; both are caused by surprising, shocking, or disturbingoccurrences. Both present with symptoms of distress; neither presents solely withsomatic symptoms~ However, nervios is a much broader illness, related more tocontinual stresses. In contrast,susto seems to be related to a single stressful event.There are a few broadly recommended treatments for nervios, while those for sustoshow more regional variation.

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF THE FOLK ilLNESS NERVIOS 331

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The core description of nervios agreed on by all four sites supports the patterns

reported in the literature for these individual populations. Nervios is felt to oc-cur more often in women. It is caused by emotion and interpersonal problems; its

symptoms are primarily nonsomatic. Interestingly, although treatment by psychol-ogists and doctors is recommended, the most broadly recommended treatment isneither biomedical nor folk, but spiritual, i.e., praying. However, at all four sites,nervios covered a broad range of mental health conditions. It would seem of great

importance for mental health professionals working with these populations to un-derstand the way the term nervios is used and the types of conditions it covers.It should be noted, however, that the literature suggests that nervios may not be

considered a "mental illness" by these populations (Baer 1996).Almost everyone approached to be interviewed for this study considered nervios

to be an illness. Thus, there is an interesting contrast in prevalence between nerviosand other common Latino folk illnesses. We have carried out parallel studies to

those described here for susto and nervios for the folk illnesses Gaida de la mollera

(fallen fontanelle) and mal de ojo (evil eye) (Weller 1997; Weller and Baer 2001).These studies indicated that in the Mexican sample, in which 100% 9f respondentsconsidered nervios to be an illness, recognition of susto was 87%, Gaida de lamollera 85%, and for mal de ojo only 63% However, recognition of susto, mal deojo, and Gaida de la mollera varied by social class. Recognition was highest in thelower class, intermediate in the working class, and lowest in the middle class. Butunlike other folk illnesses, recognition of nervios in Mexico was not class related.Similarly, we found no meaningful variation in relevant themes for nervios bydegree of acculturation. In the Texas and Connecticut samples, a very crude indexof acculturation can be estimated by birthplace and language preference. Responsesdid not differ significantly on either of these variables.

Nervios and susto are distinct entities. While it has been suggested in the liter-ature that nervios may be the "illness of choice" among ladinos (Low 1989:133)for expressing stress or distress, our data do not totally support this hypothesis.Among the ladino/mestizo populations we studied, sustois also an illness category,and it can be distinguished from nervios. The two illnesses appear to overlap, butnervios is a much broader illness and is widely recognized. People in the samecommunities recognize both illnesses, and nervios appears to transcend socialclass. Specific research would be necessary with indigenous groups to determinewhether the same pattern holds in those populations. Howeyer, in Mexico it ap-pears that the recognition of susto as an illness, Unlike that of nervios,may be class

related.Recognition of susto also varies by region. It is also important to note that

although nervios was considered to be an illness at all four sites, susto was not

332 ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

recognized as an illness by Puerto Ricans in Connecticut. During the initi_al stagesof this project (when descriptive, open ended interviews were conducted to elicit

individual explanatory models), Puerto Rican respondents indicated that they con-sidered susto to be a symptom, a feeling, but not an illness.

Finally, at least for the Mexican and Guatemalan populations, nervios (and susto;Weller et al. 2002) is implicated in the causality of diabetes. While diabetes is nota great problem at this time in Guatemala, ppssibly due to widespread malnutrition

(which reduces the prevalence of obesity), this is not the situation in Mexico. InMexico, the diabetic mortality rate for people older thano65 is several times greaterthan that in the United States (PARD 1986). Both nervios and susto need further

study exploring their possible relation to diabetes.This study demonstrates the usefulness of cross-cultural research on nervios

and of a systematic comparison with susto. We determined a core description ofnervios as well a,s similarities and differences in that definition among the fourLatino groups studied. The relationship to susto has been clarified, and a link todiabetes for at least two of the populations studied is suggested as an importantarea for further research. While the samples at each site were representative ofthe variability in each of those populations, the results cannot be generalized

to, for example, all of Mexico from the Guadalajara sample, or to all MexicanAmericans from the south Texas sample. The similarity in findings across suchdiverse samples, however, suggests that the findings would apply to many moreregions than those actually sampled. Because such strong similarities were foundin descriptions from places ranging from rural Guatemala to urban Connecticut,it is likely that those same themes would be important to Latinos in regions otherthan those sampled for this study.

Our approach also demonstrates a number of important directions for the futurestudy of these conditioI1s. First, this study of nervios demonstrates a way to studyethnomedical phenomena in their cultural contexts that also allows for cross-cultural comparisons. In this research, we used free listing to elicit the explanatorymodel (Kleinman et al. 1978) of nervios in each population being studied. Next,we developed a structured interview (a yes-no questionnaire) that incorporatedthemes from each community's explanatory model (as well as other items, someof which had biomedical origin). From this, we were able to determine whichaspects of explanatory models were shared and which were distinct. Our two-stepapproach, which incorporated themes from all sites in the interviews, allowed usto verify whether or not themes mentioned in the open-ended interviews wereimportant within a community and across communities. The advantage of thestructured interviews was that themes that were mentioned at one particular sitebut not at another could also be confirmed. Reliance on the open-ended interviewsalone may have missed some themes relevant across sites. We were also able todetermine similarities and differences between nervios and another folk illness,

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF THE FOLK ll..LNESS NERVIOS 333

susto. We therefore suggest such an approach as important and appropriate for

cross-cultural ethnomedical research.We also feel that our approach extends that of Guarnaccia and RogIer (1999).

While they emphasize the importance of describing folk illnesses within their cul-tural contexts, they particularly stress the need for anthropologists to determinehow these illnesses are related to psychiatric disorders (Guarnaccia and RogIer1999). Our work expands the relationship to include both mental and physicaldisorders. In doing so we stress the importance of questioning the mind-body di-vision of Western cultures-and of biomedicine-which discounts the relationshipbetween folk illnesses and physiological disorders. The ethnomedical systems inwhich these illnesses are embedded do not recognize a mind-body di$tinction, andindeed see a fluid relationship between the physical body and its problems, the

mind, emotions, and the spiritual. If we really want to understand folk illnesses,we need to allow for the possibility that these categorizations of symptoms maycross over the neat lines that separate the psychiatric and the physiological inthe biomedical conceptualization. In the case of nervios (and susto as previouslydemonstrated by Rubel et al. 1984 and Baer and Penzell1993), it appears that the

ethnomedicalevidence supports a relationship between nervios/susto and physio-logical as well as psychological problems. Informants' descriptions of nervios andsusto suggest a connection between nervious and susto and diabetes in two of the

populations studied. The testing of this and other reported relationships betweenfolk illnesses and biomedical diseases is clearly an important next step in our

understanding of the meaning and implicatio~s of these ethnomedical diagnoses.Biomedicine poorly understands illnesses that transcend the mind-body distinc-tion. Developing an understanding of the ethnomedical systems and diagnosesthat recognize and understand these connections may be important in augmentingthe biomedical understanding of the full dimensions and causes of human health

problems.To do so will require a broad and interdisciplinary approach. Due to the ef-

forts of Guarnaccia and colleagues, nervioshas been included in large-scale men-tal health surveys. This has allowed an estimation of the prevalence of nerviosand made possible comparisons between genders and social classes in the oc-currence of nervios. These data are critical, as they supplement the descriptivecase reports of nervios, which can only suggest possible factors related to nervios.For susto, however, there are no comparable epidemiological data. Given thatthere is considerable overlap between nervios and susto, mental health surveysof Latinos should also include susto (although it mayor may not exist as anillness category in specific ethnic groups). The addition of a few questions thatrequest information on susto would go far in providing population-based infor-mation on the prevalence of susto and its distribution across social classes and

genders.

334 ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

However, the reliance on mental health surveys for data on nervios haslimited the type of information that is available on that illness. In contrast,for susto there has been an explicit exploration by Rubel and colleagues

(1984) of the possible relation between susto and stress, depression, physio-

logical symptoms, and mortality. They found that although susto is associatedwith psychological symptoms, it is also associated with physiological out-comes. The overlap between susto and nervios suggests that more needsto be understood about the relationship between nervios and physiological

outcomes.In conclusion, we see the need for collaboration between anthropologists and

psychiatric epidemiologists in the study of nervios, susto, and other folk illnesses.Susto (and possibly other folk illnesses) needs to be included on mental health

surveys; nervios (and possibly other folk illnesses) needs to be investigated in termsof its relationship to stress, depression, physiological symptoms, and mortality. We

cannot continue to assume the separation of the health problems of the mind andthe body when the evidence suggests that such a division may just be an artifactof our own creation, which obscures rather than illuminates the reality of patternsand causality of human illnesses.

I

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the National Science Foundation grants BNS-9204555,

SBR-9727322, and BC-OI08232 to S. Weller, and SBR-9807373 and BCS-0108228 to R. Baer.

NOTES

1. The final questionnaire is available from the authors RDB or SCW upon request.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association1994 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. Washington,

DC: American Psychiatric Association.Baer, Roberta

1996 Health and Mental Health Among Mexican -American Migrant Workers: Implica-tions for Survey Research. Human Organization 55: 58-66.

Baer, Roberta, and Martha Bustillo1993 Susto and Mal de Ojo Among Florida Farm Workers: Emic and Etic Perspectives.

Medical Anthropology Quarterly 17(1): 90-100.Baer, Roberta, and Dennis Penzell

A CROSS-CULTURAL APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF THE FOLK ILLNESS NERVIOS 335

1993 Susto and Pesticide Poisoning Among Florida Fann Workers. Culture~ Medicineand Psychiatry 17(3): 321-327.

Barnett, Elyse A.1989 Notes on Nervios: A Disorder of Menopause. In Gender, Health, and illness: The

Case Of Nerves. D.L.Davis and S.M. Low, eds., pp. 67-77. New York: HemispherePublishing Co.

Camino, Linda A.1989 Nerves, Worriation, and Black Women. In Gender, Health, and lllness: The Case

Of Nerves. D.L. Davis and S.M. Low, eds., pp. 203-222. New York: HemispherePublishing Co.

Davis, Dona L., and SethaM. Low1989 Gender, Health and illness: The Case of Nerves. New York: Hemisphere Publishing

Co.Finerman, Ruthbeth

1989 The Burden of Responsibility: Duty, Depression, and Nervios in Andean Ecuador.In Gender, Health, and illness: The Case Of Nerves. D.L. Davis and S.M. Low,eds., pp. 49-65. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Co.

Finkler, Kaja1989 The Universality of Nerves. In Gender, Health, and illness: The Case Of Nerves.

D.L. Davis and S.M. Low eds., pp.79-87. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Co.1991 Physicians at Work, Patients in Pain. Boulder: Westview Press.

Guarnaccia, Peter J.1993 Ataques de Nervios in Puerto Rico: Culture-Bound Syndrome or Popular lllness.

Medical Anthropology 15: 157-165.Guarnaccia, Peter J., Roberto Lewis-Fernandez, and Melissa Rivera Marano

2003 Toward a Puerto Rican Popular Nosology: Nervios andAtaques de Nervios. Culture,Medicine and Psychiatry 27(3): 339-366.

Guarnaccia, Peter J., and Lloyd H. RogIer1999 Research on Culture-Bound Syndromes: New Directions. The American Journal

of Psychiatry 156: 1322-1327.Jenkins, Janis H.

1988 Conceptions of Schizophrenia as a Problem of Nerves: A Cross-Cultural Compar-ison of Mexican Americans and Anglo-Americans. Social Science and Medicine

26(12): 1233-1243.Kay, Margarita, and Cannen Portillo

1989 Nervios and Dysphoria in Mexican American Widows. In Gender, Health and ill-ness: The Case Of Nerves. D.L. Davis and S.M. Low, eds.,pp.181-201.New York:Hemisphere Publishing Co.

Kleinman, Arthur, Leon Eisenberg and Byron Good1978 Culture, lllness, and Care: Clinical Lessons from Anthropologic and Cross-Cultural

Research. Annals of Internal Medicine 88: 251-258.Koss-Chioino, Joan D.

1989 Experience of Nervousness and Anxiety Disorders in Puerto Rican Women: Psychi-atric and Ethnopsychological perspectives. In Gender, Health, and illness: The CaseOf Nerves. D.L. Davis and S.M. Low, eds., pp. 153-180. New York: HemispherePublishing Co.

Krieger, Laurie1989 Nerves and Psychosomatic illness: The Case of Urn Ramadan. In Gender, Health,

and illness: The Case Of Nerves. D.L. Davis and S.M. Low,eds., pp. 89-101. NewYork: Hemisphere Publishing Co.

Low, Setha1985 Culturally Interpreted Symptoms of Culture-Bound Syndromes: A Cross-Cultural

Review of Nerves. Social Science and Medicine 21(2): 187-196.

336ROBERTA D. BAER ET AL.

1989 Gender, Emotion, and Nervios in Urban Guatemala. In Gender, Health, and ill-ness: The Case Of Nerves. D.L. Davis and S.M. Low, eds., pp. 115[23]-140[48].

New York: Hemisphere Publishing Co.Pan American Health Organization (pAHO)

1986 Health Conditions in the Americas, 1981-1984. Washington, DC: Pan American

Health Organization.Rqrnney, A. Kimball, Susan C. Weller, and William Batchelder

1986 Culture and Consensus: A Theory of Culture and Informant Accuracy. American

Anthropologist 88: 313-351.Rubel, Arthur, Carl W. O'NeIl, and Rolando Collado-Ardon

1984 Susto, a Folk illness. Berkeley: University of California Press.Salgado de Snyder, V. Nelly, Maria de Jesus Diaz-Perez, and Victoria D. Ojeda

2000 The Prevalence of Nervios and Associated Symptomatology among Inhabitants ofMexican Rural Communities. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 24(4): 453-470.

Sluka, Jeffrey A.1989 Living on their Nerves: Nervous Debility in Northern Ireland. In Gender, Health,

and illness: The Case Of Nerves: D.L. Davis and S.M. Low, eds., pp. 127-151.

New York: Hemisphere Publishing Co.

Trotter, Robert, .II1982 Susto: The Context of Community Morbidity Patterns. Ethnology 21: 215-226.

Weller, Susan

1997 Latino Beliefs about Mollera Caida. Paper presented at the meetings of the Societyfor Applied Anthropology, March, Seattle, WA.

Weller, Susan, and Roberta Baer2001 Intra- and Intercultural Variation in the Definition of Five lllnesses: AIDS, Diabetes,

the Common Cold, Empacho, and Mal de Ojo. Cross-Cultural Research 35(2): 201-226.

Weller, Susan, and A. Kimball Romney1988 Systematic Data Collection. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Weller, Susan C., Roberta D. Baer, Javier Garcia de Alba Garcia, Mark Glazer,Robert Trotter, Lee Pachter, and RobertE. Klein

2002 Regional Variation in Latino Descriptions of Susto. Culture, Medicine and Psychi-atry 26(4): 449-472.

Roberta D. Baer

Department of AnthropolotyUniversity of South FloridaTampa, FL 33620

Susan C. WellerDepartment of Preventive MedicineUniversity of Texas Medical BranchGalveston, TX 77555-1153

Mark Glazer

University of Texas Pan AmericanEdinburg, TX 78539-2997

Robert TrotterDepartment of AnthropologyNorthern Arizona UniversityFlagstaff, AZ 86011

Lee PachterDepartment of PediatricsUniversity of Connecticut School of MedicineSt. Francis Hospital and Medical Center

Hartford, CTO6105

Robert E. KleinMedica! Entomology Research Training Unit/Guatemala (MERTU/G)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

![Untitled-1 [] · 2020. 10. 9. · Thi Ill I Il Ill Olli Ill Ill 1 Ill ill Ill Il Ill ill Ill 11 Ill](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/60d272307160da1c310a85a5/untitled-1-2020-10-9-thi-ill-i-il-ill-olli-ill-ill-1-ill-ill-ill-il-ill.jpg)