Hummingbird Conservation in Mexico: The Natural Protected...

Transcript of Hummingbird Conservation in Mexico: The Natural Protected...

BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, researchlibraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research.

Hummingbird Conservation in Mexico: The Natural Protected Areas SystemAuthor(s): M.C. Arizmendi, H. Berlanga, C. Rodríguez-Flores, V. Vargas-Canales, L. Montes-Leyva andR. LiraSource: Natural Areas Journal, 36(4):366-376.Published By: Natural Areas AssociationDOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3375/043.036.0404URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3375/043.036.0404

BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, andenvironmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books publishedby nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses.

Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance ofBioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use.

Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiriesor rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder.

366 Natural Areas Journal Volume 36 (4), 2016

ABSTRACT: Hummingbirds represent an avian family restricted to the Americas that feeds mainly on nectar obtained from ornithophilous plants. In North America (Mexico-USA-Canada), 58 species have been reported out of the 330 total hummingbird species, all of them occurring in Mexico. In this work we analyzed the distribution of hummingbirds in relation to the coverage of the natural protected area system in Mexico using a complementarity analysis to assess the minimum set of areas needed to protect all species. We focused our search mainly to biosphere reserves, as these areas have complete bird lists. Six biosphere reserves included 93% of the hummingbird species. Four species were not included in any biosphere reserve or other natural protected area. To preserve those species, three important bird areas (AICAs as they are known in Spanish) are needed. With these nine areas, all hummingbird species are included. Hummingbird distributions can be classified in six groups that distribute following the major biogeographic regions described for Mexico, including groups using; (1) the main mountain ranges, (2) the Pacific tropical dry forests, (3) the Gulf of Mexico slopes with tropical dry forest, (4) the humid tropical forest in southern Mexico, and both (5) Yucatan and (6) Baja California peninsulas.

Index terms: AICA, biosphere reserves, endemic species, hummingbird conservation, Mexico

INTRODUCTION

Hummingbirds represent a New World bird family comprising approximately 330 species. They are small birds (2.5–24 g) that feed on nectar obtained from flowers using long bills and protrusible tongues and also feed to some extent on insects (Arizmendi and Berlanga 2014). Hummingbirds visit a large number of wildflowers and pollinate many of them (Arizmendi and Rodriguez Flores 2012). They also pollinate some cultivated plants that are important both ecologically and economically for humans, such as pineapples (Cabral et al. 2000; Carlier et al. 2007). For some plant species, such as some Heliconia, Datura, Fuchsia species, hummingbirds are the exclusive pollinators, being the only ones responsible for their sexual reproduction (i.e., Altshuler and Clark 2003). For others, they repre-sent part of a wider array of pollinators (Arizmendi and Rodríguez-Flores 2012). However, for other plants, hummingbirds may not represent a benefit as pollinators; in some cases, they can rob nectar without contacting plant reproductive structures (i.e., Arizmendi et al. 1996; Arizmendi 2001). In addition to their ecological importance, hummingbirds have always been important to human culture (i.e., Mazariegos 2010), representing gods, soul carriers, and fecundity among prehispanic societies, as well as good luck, love, and wellness, even in modern societies.

In Mexico, 58 species have been described (Arbelaez and Navarro 2014; Arizmendi and Berlanga 2014) representing all the

hummingbird fauna of North America. From these nine are Neotropical migrants that breed in the United States and Canada and have their wintering grounds in Mex-ico, including, for example, Selasphorus rufus Gmelin, JF, S. platycercus Swainson, and Archilochus colubris L. Tropical spe-cies, such as hermits (Phaethornis spp.) and mangos (Colibri thalassinus Swain-son, Anthracotorax prevostii Lesson) are distributed mainly in Mexican southern tropical forests. Endemic species com-prise an important group with species of very small distribution, such as Lophornis brachylophus Moore, RT, distributed only in 50 km2 of temperate forests at Guerrero, or Eupherusa polyocerca Elliot and Eu-pherusa cyanophrys Rowley & Orr with 4000 and 4100 km2 in Guerrero and Oaxaca México (del Hoyo et al. 2014). Of the 58 species represented in Mexico, six are considered endangered at the global level (IUCN 2015)—all of them endemics with a restricted range (Berlanga et al. 2008). The main threat for Mexican hummingbirds is habitat loss and fragmentation (Arizmendi and Berlanga 2014).

Mexico has a national Natural Protected Areas System that includes biosphere reserves, national monuments, national parks, as well as other state protected areas (SINAP www.conanp.gob.mx). The whole system comprises 177 areas and 25,628,239 ha of the country’s territory.

The purpose of this work was to analyze the opportunities and threats to humming-bird conservation in México considering protection provided by the Mexican Natural

Natural Areas Journal 36:366–376

3 Corresponding author: [email protected]; 521-5556237002

•

Hummingbird Conservation in

Mexico: The Natural Protected Areas

System

M.C. Arizmendi1,3

1Unidad de Biología Tecnologíay Prototipos

FES Iztacala, UNAM. Av. De losBarrios 1

Los Reyes Iztacala México 54090México

H. Berlanga2

C. Rodríguez-Flores1

V. Vargas-Canales2

L. Montes-Leyva1

R. Lira1

2NABCI CONABIOLiga Periférico - Insurgentes Sur

Núm. 4903Col. Parques del PedregalDelegación Tlalpan, 14010

México, D.F.

•

Volume 36 (4), 2016 Natural Areas Journal 367

Protected Areas System, and in the context of both national and international laws.

METHODS

Conservation status both at the national and international level for hummingbird species was assessed using available information at avesmx (Berlanga et al. 2008). For the 58 Mexican species, the distributional status (endemic, quasiendemic, resident, or migrant) was determined using literature (Howell and Webb 1995; Arizmendi and Berlanga 2014), distributional databases (averAves, eBird), and personal data. Bio-sphere reserves and Important Bird Areas were included as they have complete bird lists. Complementarity analysis for com-pletion of the minimum set of protected areas needed to achieve all hummingbird conservation was carried out. We used the method proposed by Possingham et al. (1993) and performed by other authors for different plant groups from Mexico (i.e., Lira et al. 2002; Villaseñor et al. 1998). A data matrix was prepared with presence/absence data of the 58 humming-bird species in the 51 protected areas (41 biosphere reserves and 10 Important Bird Areas (AICAs in Mexico)); the comple-mentarity algorithm was performed using the tool SOLVER (Excel® 2010, Microsoft Corp., 2010). Finally, distribution was an-alyzed using a cluster ordination method (JMP SAS Inc.) in order to find groups of hummingbirds with common conservation needs based on their distribution.

RESULTS

From the 58 hummingbird species reported for Mexico, six (10.3%) are listed in the IUCN red list of threatened species (two Almost Threatened, two Vulnerable, one Endangered, and one Critically Endan-gered), and 17 within Mexican law (six under Special Protection, nine Threatened, two Endangered) (Table 1). All of six glob-ally threatened species are also Mexican endemics with restricted distributions in the country, while seven of the 17 species listed in Mexican laws are also endemics (Table 1). There are another six endemic species that, in spite of having a restricted distributional range, are not listed as en-

dangered, such as Atthis eliotti Ridgway, mainly because they can be considered locally abundant. Ten species are migrants (17.2%), of which five are long distance migrants that breed in the northern United States and Canada and spend the winter in Mexico and Central America.

Hummingbirds are widely distributed in the country, being reported in 146 (out of the 171) Natural Protected Areas, includ-ing all the biosphere reserves (41). Of the 58 species, only three are not included in any biosphere reserve or natural protected area: Lophornis brachylophus, Eupherusa cyanophrys, and Eupherusa poliocerca. These three species are highly restricted (Figure 1) and, therefore, threatened by habitat destruction and fragmentation. They are included in two declared Important Bird Areas: Sierra de Atoyac (Lophornis brachylophus and Eupherusa poliocerca), and Sierra de Miahuatlán (Eupherusa cyanophrys).

Complementarity analysis showed that it is enough to preserve six biosphere reserves and three Mexican IBAs (AICAs) to have all hummingbird species (58 species) at least represented in one area. These ar-eas are Selva el Ocote (32 hummingbird species), Manantlán (23), Montes Azules (22), Sian Ka´an (10), Sierra La Laguna (4), Tehuacán-Cuicatlán (18), and the IBAs are Cozumel (4), Sierra de Atoyac (25), and Sierra de Miahuatlan (23) (Table 2). There were species represented only in one area (18 species, Table 3), in two areas (11 species), in three areas (10 species), and between four and eight areas (19 species). From the endemic species (13), two were not represented in any area, eight were represented in one area, two in two areas, and one in three areas (Table 3). From the nine areas detected as the minimum set for hummingbird conservation, only Montes Azules did not represent any endemic species (Figure 2).

Two protected areas hold 81% of the Mexi-can hummingbird species—Selva el Ocote, with 32 species, and Sierra de Manantlán with 15 more—for a total of 47 out of the 58 found in Mexico (Figure 2). The remaining seven areas contributed either one or two species to complete the entire set (Figure

2). Selva el Ocote is a big area situated in Central Chiapas in southern Mexico. It is an area with an altitudinal range from 180 to 1500 m and with 10 vegetation types represented, mainly Tropical Deciduous Forest, Tropical Semi-deciduous Forest, Humid Forest, Oak and Pine-Oak Forests, and Cloud Forest (SEMARNAT/CONANP 2001). Its hummingbird fauna reflects this habitat variation. Species present include the tropical humid forest related species such as Campylopterus excellens Wetmore, C. rufus Lesson, Lamprolaima rhami Lesson, Abeillia abeillei Lesson & Delattre, and Florisuga mellivora L., sub-humid and dry forest species such as Heliomaster constantii Delattre or Amazilia yucatanensis Cabot, but also species typical of the temperate forests (Pine-oak, Pine and Cloud forests) such as Amazilia be-ryllina Deppe, Eugenes fulgens Swainson, Hylocharis leucotis Vieillot, and Colibri thalassinus. In this area it is possible to find 55% of all the species found in Mexico. The next area chosen by the complementarity analysis is Sierra de Manantlán, which contributed 15 additional species. Sierra de Manantlán is a biosphere reserve sit-uated in western Mexico in the mountain ranges that go from north to south along the Pacific slope (Sierra Madre Occiden-tal) and is covered mainly with temperate forests (Pine-oak, Oak, and Cloud), with dry and sub-humid forests in the lowlands (SEMARNAT/CONANP 2000) (Figure 2). This area contributes species typical of mountain ranges such as Atthis heloisa Lesson & Delattre, Amazilia violiceps Gould, Lampornis clemenciae Lesson, and long distance migrants as Selaspho-rus rufus, S. platycercus, and Archilochus alexandri Bourcier & Mulsant. Montes Azules, an area covered by humid tropical forest situated in south central Chiapas, contributed two tropical species, Heliothryx barroti Bourcier and Phaeochroa cuvierii Delattre & Bourcier, at their northernmost distribution. Sierra de Atoyac, an area cov-ered by temperate forests (Pine-oak, Oak, and Cloud forest) and dry to semi-humid forests in the lower parts in the southern state of Guerrero, contributed two more restricted endemic species, Eupherusa poliocerca and Lophornis brachylophus. Tehuacán-Cuicatlán biosphere reserve is an area representing a dry central desert cov-

368 Natural Areas Journal Volume 36 (4), 2016

Tab

le 1

. End

emic

hum

min

gbir

d sp

ecie

s co

nsid

ered

in

dang

er i

n M

exic

an l

aws

(NO

M-0

59),

at

the

glob

al l

evel

(IU

CN

), a

nd n

umbe

r of

are

as o

f th

e m

inim

um s

et f

ound

in

this

ana

lysi

s w

here

the

y ca

n be

fou

nd.

Spec

ies

Com

mon

Nam

e N

OM

-059

IUC

ND

istr

ibut

ion

Num

ber

of A

reas

W

here

Can

Be

Foun

dA

reas

of t

he M

inim

um S

et

Abei

llia

abei

llei

Emer

ald-

chin

ned

Hum

min

gbird

(C

olib

rí Pi

co C

orto

)U

nder

Spe

cial

Pr

otec

tion

Leas

t C

once

rn6

El O

cote

, Mon

tes A

zule

s

Amaz

ilia

viri

difr

ons

Gre

en F

ront

ed H

umm

ingb

ird

(Col

ibrí

Fren

te V

erde

)Th

reat

ened

Leas

t C

once

rnEn

dem

ic8

El O

cote

, Ato

yac,

Mia

huat

lán

Atth

is e

lliot

iW

ine-

thro

ated

Hum

min

gbird

(Z

umba

dor G

uate

mal

teco

)Th

reat

ened

Leas

t C

once

rn5

El O

cote

, Mon

tes A

zule

s

Atth

is h

eloi

saB

umbl

ebee

Hum

min

gbird

(Z

umba

dor M

exic

ano)

Leas

t C

once

rnEn

dem

ic10

Man

antlá

n, A

toya

c, T

ehua

cán,

M

iahu

atlá

n

Cal

otho

rax

luci

fer

Luci

fer H

umm

ingb

ird (C

olib

rí Lu

cife

r)Le

ast

Con

cern

8M

anan

tlán,

Teh

uacá

n,

Mia

huat

lán

Cal

otho

rax

pulc

her

Bea

utifu

l Hum

min

gbird

(Col

ibrí

Oax

aque

ño)

Leas

t C

once

rnEn

dem

ic2

Tehu

acán

-Cui

catlá

n

Cam

pylo

pter

us e

xcel

lens

Long

Tai

led

Sabr

ewin

g (F

anda

ngue

ro C

ola

Larg

a)U

nder

Spe

cial

Pr

otec

tion

Alm

ost

thre

aten

edEn

dem

ic &

re

stric

ted

2El

Oco

te

Cam

pylo

pter

us ru

fus

Ruf

ous S

abre

win

g (F

anda

ngue

ro

Can

elo)

Und

er S

peci

al

Prot

ectio

nLe

ast

Con

cern

5El

Oco

te

Chl

oros

tilbo

n au

rice

psG

olde

n C

row

ned

Emer

ald

(Esm

eral

da M

exic

ana)

Leas

t C

once

rnEn

dem

ic3

Man

antlá

n, A

toya

c,

Mia

huat

lán

Chl

oros

tilbo

n fo

rfic

atus

Esm

eral

da d

e C

ozum

el (C

ozum

el

Emer

ald)

Leas

t C

once

rnEn

dem

ic &

re

stric

ted

1C

ozum

el

Cyn

anth

us so

rdid

usD

usky

Hum

min

gbird

(Col

ibrí

Osc

uro)

Leas

t C

once

rnEn

dem

ic2

Tehu

acán

-Cui

catlá

n

Dor

icha

eliz

a M

exic

an S

hear

tail

(Col

ibrí

Col

a H

endi

da)

Enda

nger

edA

lmos

t th

reat

ened

Ende

mic

&

rest

ricte

d4

Sian

Ka´

an

Dor

icha

eni

cura

Slen

der S

hear

tail

(Col

ibrí

Tije

reta

Gua

tem

alte

co)

Thre

aten

edLe

ast

Con

cern

2Si

an K

a´an

Euph

erus

a cy

anop

hrys

Blu

e C

appe

d H

umm

ingb

ird

(Col

ibrí

Oax

aque

ño)

Thre

aten

edEn

dang

ered

Ende

mic

&

rest

ricte

d1

Mia

huat

lán

Euph

erus

a po

lioce

rca

Whi

te T

aile

d H

umm

ingb

ird

(Col

ibrí

Col

a B

lanc

a)Th

reat

ened

Vul

nera

ble

Ende

mic

&

rest

ricte

d1

Ato

yac

Hel

iom

aste

r lon

giro

stri

sLo

ng-b

illed

Sta

rthro

at (C

olib

rí pi

cudo

gar

gant

a az

ul)

Und

er sp

ecia

l pr

otec

tion

Leas

t C

once

rn9

Mon

tes A

zule

s, El

Oco

te,

Ato

yac,

Mia

huat

lán

Con

tinue

d

Volume 36 (4), 2016 Natural Areas Journal 369

ered with dry shrubs and columnar cacti, and dry forest, mainly with short Pine-Oak forests in the higher parts. It contributed two typical dryland species, Calothorax pulcher and Cynanthus sordidus. Sierra de la Laguna, situated in the Baja Cali-fornia peninsula, represents a mountain range surrounded by a dry desert. This is the habitat of an endemic hummingbird, Hylocharis xanthusii Lawrence, found in these lands. In its low dry shrub lands and in the oak land, Calypte anna Lesson can be found. Two more areas contributed one species each: Cozumel with the endemic species Chlorostilbon forficatus Ridgway, and Sierra de Miahuatlán with Eupherusa cyanophrys.

Analyzing the distribution of humming-birds using a Cluster Analysis (Figure 3), six different groups were formed. From the bottom, a group formed by the more widespread species, all from the tropical dry forests that cover the Pacific and Gulf slopes of Mexico, such as Amazilia rutila Delattre. Another one formed by the spe-cies that are distributed in the Gulf slope extending to the Yucatan Peninsula, such as Amazilia candida Bourcier & Mulsant and A. yucatanensis. Another group com-prised species of the dry lands of western Mexico, such as Calypte anna. Another big group contained species that distrib-ute along mountain ranges of the Sierra Madre Oriental and Occidental extending to Sierra Madre del Sur, such as Amazilia beryllina and Hylocharis leucotis. Next, another big group was composed of re-stricted range species represented only in one area, such as Lophornis brachylophus, or species that were more widespread but represented here in only one area, such as Phaethonis mexicanus Hartert, E. Finally, at the top, are tropical species that follow the distribution of the tropical humid for-ests in Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Veracruz to southern Tamaulipas, such as Lamprolaima rhami Lesson. Long distance migrants were clustered with similar residents that share distribution with them, except for Selasphorus sasin Lesson, which clustered with species with restricted distribution. This is a result of deficient data regarding its winter distribution derived mainly from identification problems that, in many cases, lead to its misidentification as S. rufous.T

able

1.

(Con

tinu

ed)

End

emic

hum

min

gbir

d sp

ecie

s co

nsid

ered

in

dang

er i

n M

exic

an l

aws

(NO

M-0

59),

at

the

glob

al l

evel

(IU

CN

), a

nd n

umbe

r of

are

as o

f th

e m

inim

um s

et f

ound

in

this

an

alys

is w

here

the

y ca

n be

fou

nd.

Spec

ies

Com

mon

Nam

e N

OM

-059

IUC

ND

istr

ibut

ion

Num

ber

of A

reas

W

here

Can

Be

Foun

dA

reas

of t

he M

inim

um S

et

Hel

ioth

ryx

barr

oti

Purp

le-c

row

ned

Fairy

(Col

ibrí

Had

a En

mas

cara

da)

Thre

aten

edLe

ast

Con

cern

1M

onte

s Azu

les

Hyl

ocha

ris x

antu

sii

Xan

tus’

s Hum

min

gbird

(Zaf

iro

de X

antu

s)Le

ast

Con

cern

Ende

mic

2La

Lag

una

Lam

porn

is c

lem

enci

aeB

lue-

thro

ated

Hum

min

gbird

Leas

t C

once

rn14

Man

antlá

n, T

ehua

cán,

Ato

yac,

M

iahu

atlá

n

Lam

porn

is v

irid

ipal

lens

Gre

en-th

roat

ed M

outa

in-g

em

(Col

ibrí

garg

anta

ver

de)

Und

er sp

ecia

l pr

otec

tion

Leas

t C

once

rn5

Mon

tes A

zule

s, El

Oco

te

Lam

prol

aim

a rh

ami

Gar

net-t

hroa

ted

Hum

mig

bird

(C

olib

rí m

ultic

olor

)Th

reat

ened

Leas

t C

once

rn6

El O

cote

, Teh

uacá

n, A

toya

c,

Mia

huat

lán

Loph

orni

s bra

chyl

ophu

sSh

ort C

rest

ed C

oque

tte (C

oque

ta

Cre

sta

Cor

ta)

Enda

nger

edC

ritic

ally

En

dang

ered

Ende

mic

&

rest

ricte

d1

Ato

yac

Loph

orni

s hel

enae

Bla

ck C

rest

ed C

oque

tte (C

oque

ta

Cre

sta

Neg

ra)

Thre

aten

edLe

ast

Con

cern

6M

onte

s Azu

les,

El O

cote

Phae

thor

nis m

exic

anus

Leas

t C

once

rnEn

dem

ic4

Man

antlá

n, A

toya

c,

Mia

huat

lán

Thal

uran

ia ri

dgw

ayi

Mex

ican

Woo

dnym

ph (N

infa

M

exic

ana)

Und

er sp

ecia

l pr

otec

tion

Vul

nera

ble

Ende

mic

&

rest

ricte

d2

Man

antlá

n

Tilm

atur

a du

pont

iiSp

arkl

ing-

taile

d W

oods

tar

(Col

ibrí

Col

a Pi

nta)

Thre

aten

edLe

ast

Con

cern

12

Mon

tes A

zule

s, El

Oco

te,

Man

antlá

n, T

ehua

cán,

Ato

yac,

M

iahu

atlá

n

370 Natural Areas Journal Volume 36 (4), 2016

Figure 1. Distribution of the endemic species of hummingbirds found in Mexico, including (a) restricted range species, and (b) more widespread ones. Note that Phaethornis mexicanus is not included as more work is needed in this recently recognized species.

Volume 36 (4), 2016 Natural Areas Journal 371

DISCUSSION

Hummingbirds represent an American family of birds that depend on nectar offered by plants to survive (Schuchmann 1999; Arizmendi and Berlanga 2014). In Mexico, a diverse array of hummingbird species can be found, including tropical species that reach their northern distri-butional range (some Hermits, Mangos, Topazes, and Coquettes), and a diverse and numerous variety of classical species of North America, including the Mountain gems, Emeralds, and Bees of McGuire et al. (2009). Hummingbirds move both lati-tudinally and attitudinally following floral resources that experience huge seasonal variations (Johnsgard 1997; Schuchmann 1999). This can explain the big contri-bution of reserves such as El Ocote and Manantlán in preserving hummingbird diversity, where long gradients of altitude and vegetation cover may support large arrays of hummingbirds—81% of all hummingbird species between the two areas. However, to achieve representation of the 11 remaining species, the model added seven more areas. Four of these were biosphere reserves, added to include species of specific habitats, such as desert enclaves (Tehuacán-Cuicatlán), or specific habitat in peninsular ecosystems (Sierra la Laguna and Sian Ka´an), or habitat for tropical species not included in a tropical humid forest of El Ocote, (Montes Azules). Nevertheless, despite adding these areas,

four endemic, restricted, and endangered species were still not covered. In order to fulfill this goal, AICAs (Important Bird Areas) were included in the analysis. These areas are not protected areas, but are recognized as areas important and needed for bird conservation (Arizmendi and Márquez Valdelamar 2000; Aguirre et al. 2006; Berlanga et al. 2008). The four species not included in areas of the Natural Protected Areas system are in urgent need of protection. First, Chlorostilbon forficatus is endemic to Cozumel Island, which has been declared a national park (Arrecifes de Cozumel) that includes coastal vegetation and is an Important Bird Area (Arizmendi et al. 2013b). This species uses the dry tropical forest and its edges to forage. Breeding biology and foraging ecology of this species are not known, and no further details on its abundance are known as far as considering it locally abundant (Arizmendi et al. 2013b). Eupherusa cy-anophrys is an endemic species of Sierra de Miahuatlán, Oaxaca, in an altitudinal range between 700 and 2600 m (Collar et al. 1992; Howell and Webb 1995). It is considered a species at greatest risk of extinction by Partners in Flight (Berlanga et al. 2010), and based on determinations of habitat loss, Berlanga et al. (2010) estimated that 15–49% of its population has been lost during the last century. The main risk associated with this decline is habitat loss (Arizmendi et al. 2013a). No protected area is within its distributional

range. The Sierra de Miahuatlán must be protected if conservation of this endemic species is a priority. Two more species, distributed only at the Sierra de Atoyac, Guerrero, México, are not included in any other protected area (Navarro 1992). One of them is Eupherusa poliocerca, an endemic species of the humid temperate forests (Pine, pine-oak, and cloud) of the Sierra de Atoyac, Guerrero. So far, only one nest was described in 1894, and ap-parently, breeding time is from February to May and from September to October (Arizmendi et al. 2013c). It is also consid-ered a highly vulnerable species by Partners in Flight (Berlanga et al. 2010). Based on determinations of habitat loss, Berlanga et al. (2010) estimated that 15–49% of its population has been lost during the last century. Population declines are mainly due to habitat loss, making it very important to formally protect its distributional area. The second species is Lophornis brachylophus, a critically endangered species because it is only known from a 25-km transect between Paraiso and Nueva Delhi at the Sierra de Atoyac mountain range (Arizmendi et al. 2010). Very little is known about its feeding ecology and breeding biology. The protection of Sierra de Atoyac is urgent, as these two endemic and restricted species depend on it for their preservation. Hummingbird distributions seem to follow closely the biogeographical regionalization proposed by Morrone (2005). There is

Table 2. Minimum set of areas needed to preserve at least one site of occurrence for each species of Mexican hummingbird.

Protected Area Area (ha) Bird Species Hummingbird SpeciesMontes Azules 331,200 464 22El Ocote 101,288 353 32Sian Ka´an 528,148 385 10Manantlán 139,577 341 23Sierra La Laguna 112,437 110 4Tehuacán-Cuicatlán 490,187 144 18AICA Cozumel 17,565 271 4AICA Sierra de Atoyac 171,673 347 25AICA Sierra de Miahuatlán 248,802 297 23Total Area 2,140,877

372 Natural Areas Journal Volume 36 (4), 2016

Table 3. Presence of hummingbirds in the minimum area set to preserve Mexican hummingbird species.

Species Mon

tes A

zule

s

El O

cote

Sian

Ka´

an

Man

antlá

n

Sier

ra L

a L

agun

a

Teh

uacá

n-C

uica

tlám

AIC

A C

ozum

el

AIC

A S

ierr

a de

Ato

yac

AIC

A S

ierr

a de

Mia

huat

lán

Abeillia abeillei 1 1Amazilia beryllina 1 1 1 1 1 1Amazilia candida 1 1 1Amazilia cyanocephala 1 1Amazilia cyanura 1Amazilia rutila 1 1 1 1 1Amazilia tzacatl 1 1 1 1Amazilia violiceps 1 1 1 1Amazilia viridifrons 1 1 1Amazilia yucatanensis 1 1 1Anthracothorax prevostii 1 1 1 1 1 1Archilochus alexandri 1 1Archilochus colubris 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1Atthis ellioti 1 1Atthis heloisa 1 1 1 1Calothorax lucifer 1 1 1Calothorax pulcher 1Calypte anna 1Calypte costae 1 1Campylopterus curvipennis 1 1 1Campylopterus excellens 1Campylopterus hemileucurus 1 1 1Campylopterus rufus 1Chlorostilbon auriceps 1 1 1Chlorostilbon canivetii 1 1 1Chlorostilbon forficatus 1Colibri thalassinus 1 1 1 1 1Cynanthus latirostris 1 1 1 1 1Cynanthus sordidus 1Doricha eliza 1Doricha enicura 1Eugenes fulgens 1 1 1 1 1Eupherusa cyanophrys 1Eupherusa eximia 1 1

Continued

Volume 36 (4), 2016 Natural Areas Journal 373

a group that distributes in the Montane Region comprising the Sierra Madre Occcidental, Sierra Madre Oriental, Eje Neovolcanico transversal, and Sierra Madre del Sur (also Rzedowski 1978). This region is what Cabrera and Willink (1973) proposed as the Mesoamerican montane region. Another group distributes along the tropical dry forest in the Pacific Gulf slopes. In more humid forests, such as tropical evergreen or humid forest, some

species distribute along the Gulf slope and its continuation into central Chiapas and Oaxaca, where well-preserved extensions of humid forests still persist. Species dis-tributed in the Yucatan and Baja California peninsulas form two other groups.

Hummingbirds in Mexico distribute in all vegetation types (Rzwedoski 1978). The short set of protected areas needed for their conservation reflect the representation of

those big vegetation types as well as the clustering. However, it has been shown that especially montane forests (Hernán-dez-Baños et al. 1995; Toledo-Aceves et al. 2011) and tropical forests (Quesada et al. 2009; Miles et al. 2006) represent highly threatened habitats in Mexico, with heavy rates of deforestation and fragmentation. Because 81% of the hummingbird species distribute on those threatened and frag-mented habitats, their continuity must be

Table 3 (Continued). Presence of hummingbirds in the minimum area set to preserve Mexican hummingbird species.

Species Mon

tes A

zule

s

El O

cote

Sian

Ka´

an

Man

antlá

n

Sier

ra L

a L

agun

a

Teh

uacá

n-C

uica

tlám

AIC

A C

ozum

el

AIC

A S

ierr

a de

Ato

yac

AIC

A S

ierr

a de

Mia

huat

lán

Eupherusa poliocerca 1Florisuga mellivora 1 1Heliomaster constantii 1 1 1 1Heliomaster longirostris 1 1 1 1Heliothryx barroti 1Hylocharis eliciae 1Hylocharis leucotis 1 1 1 1 1Hylocharis xantusii 1Lampornis amethystinus 1 1 1 1Lampornis clemenciae 1 1 1 1Lampornis viridipallens 1 1Lamprolaima rhami 1 1 1 1Lophornis brachylophus 1Lophornis helenae 1 1Phaeochroa cuvierii 1Phaethornis longirostris 1 1Phaethornis mexicanus 1 1 1Phaethornis striigularis 1 1 1Selasphorus calliope 1 1Selasphorus platycercus 1 1 1 1Selasphorus rufus 1 1 1 1Selasphorus sasin 1Thalurania ridgwayi 1Tilmatura dupontii 1 1 1 1 1 1

374 Natural Areas Journal Volume 36 (4), 2016

added as a national conservation priority.

The addition of three IBAs (AICAs) as natural protected areas will ensure the conservation of very restricted humming-bird endemic species. Protection of those areas is strongly needed and they should be included in the national system of protected areas.

Along with it, environmental education on the importance of bird conservation and on the benefits of community involvement in conservation is of primary importance (Berlanga et al. 2008). Hummingbirds represent a good group for this, as they are loved by people that recognize them as carriers of good feelings, which also makes their protection important. Using hummingbirds as flagship species can ensure the conservation of their habitats, which also preserves many other species.

María del Coro Arizmendi is currently a full time professor at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. She has a BS and a PhD in Ecology from Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Her research inter-ests include pollination ecology, especially hummingbirds as plant pollinators and hummingbird conservation ecology.

Humberto Berlanga is currently the Mex-ican National Coordinator of the North American Bird Conservation Initiative (NABCI), working at CONABIO. He has a BS in Biology from the Universidad Na-cional Autónoma de México. His research interests include bird conservation, bird monitoring, and community monitoring efforts, as well as international cooperation for bird conservation.

Claudia Rodriguez-Flores is currently a PhD student at Posgrado en Ciencias Bi-ológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma

de México. She has a BS from Universidad Nacional de Colombia and a MSc at Uni-versidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Her research interests include humming-bird–plant interactions and hummingbird conservation.

Víctor Vargas-Canales is currently a data base manager and mapping specialist at the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, CONABIO, México. He has a BS in Biology from Universidad Nacio-nal Autónoma de México. His research interests include bird conservation, bird monitoring, and community monitoring efforts, as well as international cooperation for bird conservation.

L. Montes-Leyva is currently a BS student at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, interested in the study of plant pollination, plant conservation, and eth-nobotany.

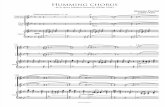

Figure 2. Minimum set of areas needed to preserve at least one site of occurrence for each species of Mexican hummingbird.

Volume 36 (4), 2016 Natural Areas Journal 375

Rafael Lira-Saade is currently a full time professor at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. He has a BS and a PhD in Sciences from Universidad Na-cional Autónoma de México. His research interests include plant pollination, plant conservation, and ethnobotany.

LITERATURE CITED

Aguirre, C., M. Altamirano, M.C. Arizmendi, H. Benitez, H. Berlanga, H. Cabral, R. Clay, J. Correa, A. Cruz, M. Cruz, M. Escobar,

E. Enkerlin, G. García-Deras, E. Gó-mez-Linares, J. González, M. González, F. González-García, M. Grosselet, O. Hinojosa, E. Iñigo, A. Jiménez, A. Lira, S. López, A. Oliveras, E. Martinez-Leyva, B. McKinnon, J. Montejo, M. Murguía, A. Navarro, R. Ortiz-Pulido, A. Panjabi, M. Pérez, O. Ro-jas-Soto, A. Rojo, I. Ruvalcaba, J. Salgado, L. Sánchez-Gonzalez, E. Santana, C. Tejeda, R. Vidal, F. Villaseñor, L. Villaseñor, R. Villegas-Patraca, C. Wood, P. Wood. 2006. Taller para la identificación de prioridades para la conservación de aves en la red de AICAS y ANP de México. Cuernavaca Morelos, 28 agosto–1 septiembre de 2006.

En: Pagina de la red de Conocimientos sobre las Aves de México (AVESMX). NABCI/CONABIO, BIRDLIFE INTL. 2008.

Altshuler, D.L., and C.J. Clark. 2003. Darwin´s Hummingbirds. Science 300:588-589.

Arbelaéz-Cortés, E., and A. Navarro-Siguenza. 2014. Molecular evidence of the taxonomic status of western Mexican populations of Phaethornis longirostris (Aves: Trochilidae). Zootaxa 3716:81-97.

Arizmendi, M.C. 2001. Multiple ecological interactions: The case of the hummingbird pollination and the nectar robber Diglossa baritula. Canadian Journal of Zoology 79:997-1006.

Arizmendi M.C., and H. Berlanga. 2014. Colibríes de México y NorteAmérica/Hum-mingbirds of Mexico and North America. CONABIO. México.

Arizmendi, M.C., C. Domínguez, and R. Dirzo. 1996. The role of an avian nectar robber and of hummingbird pollinators in the re-production of two plant species. Functional Ecology 10:119-127.

Arizmendi, M.C., and L. Márquez-Valdelamar. 2000. Areas de Importancia para la Con-servación de las Aves en México. CIPA-MEX-Fondo Mexicano para la Conservación de la Naturaleza, México.

Arizmendi M.C., and C. Rodríguez-Flores. 2012. How many plant species do hum-mingbirds visit? Ornitología Neotropical 23 (Supplement):71-77.

Arizmendi, M.C., C. Rodríguez-Flores, and C. Soberanes-González. 2010. Short-crested Coquette (Lophornis brachylophus). Neo-tropical Birds Online, T.S. Schulenberg, ed. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. <http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/portal/species/overview?p_p_spp=241691>.

Arizmendi, M.C., C. Rodríguez-Flores, C. So-beranes-González, and Thomas S. Schulen-berg. 2013a. Blue-capped Hummingbird (Eupherusa cyanophrys). T.S. Schulenberg, ed., Neotropical Birds Online, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. <http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/portal/species/overview?p_p_spp=256536>.

Arizmendi, M.C., C. Rodríguez-Flores, C. Soberanes-González, and Thomas S. Schulenberg. 2013b. Cozumel Emerald (Chlorostilbon forficatus), T.S. Schulenberg, ed., Neotropical Birds Online, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. <http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/portal/species/overview?p_p_spp=244251>.

Arizmendi, M.C., C. Rodríguez-Flores, C. So-beranes-González, and Thomas S. Schulen-berg. 2013c. White-tailed Hummingbird (Eupherusa poliocerca). T.S. Schulenberg, ed., Neotropical Birds Online, Cornell Lab

Figure 3. Cluster analysis of the distribution of Mexican hummingbirds.

376 Natural Areas Journal Volume 36 (4), 2016

of Ornithology. <http://neotropical.birds.cornell.edu/portal/species/overview?p_p_spp=256696>.

Berlanga, H., J.A. Kennedy, T.D. Rich, M.C. Arizmendi, C.J. Beardmore, P.J. Blancher, G.S. Butcher, A.R. Couturier, A.A. Dayer, D.W. Demarest, W.E. Easton, M. Gustafson, E. Iñigo-Elias, E.A. Krebs, A.O. Panjabi, V. Rodriguez Contreras, K.V. Rosenberg, J.M. Ruth, E. Santana Castellón, R. Ma. Vidal, and T.C. Will. 2010. Saving our shared birds: Partners in Flight tri-national vision for landbird conservation. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY.

Berlanga, H., V. Rodríguez-Contreras, A. Oliveras de Ita, M. Escobar, L. Rodríguez, J. Vieyra, and V.Vargas. 2008. Red de Conocimientos sobre las Aves de México (AVESMX). CONABIO.

Cabral J.R.S., G.C. d´Eeckenbragge, and A.P. deMatos. 2000. Introduction of selfing in pineapple breeding. Acta Hort 529:165-168.

Cabrera A.L., and A. Willink. 1973. Bio-geografía de América Latina. Monografía 13, Serie Biología, Organización de los Estados Americanos, Washington, DC.

Carlier J.D., G.C. d´Eeckenbrugge, and J.M. Leitao. 2007. Pineapple. Pp. 331-342 in C. Kole, ed., Fruits and Nuts, Chapter 18, Volume 4. Genome Mapping and Molecular Breeding in Plants. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Collar, N.J., L.P. Gonzaga, N. Krabbe, A. Ma-droño Nieto, L.G. Naranjo, T.A. Parker III, and D.C. Wege. 1992. Threatened Birds of the Americas. The ICBP/IUCN Red Data Book. Third edition, part 2. International Council for Bird Preservation, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

del Hoyo, J., N.J. Collar, D.A. Christie, A. El-liott, and L.D.C Fishpool. 2014. HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World. Lynx Edicions and BirdLife International, Barcelona, Spain,

and Cambridge, UK.

Hernández-Baños, B., A.T. Peterson, A. Navar-ro-Sigüenza, and P. Escalante-Pliego. 1995. Bird faunas of the humid montane forest of Mesoamerica: Biogeographic patterns and priorities for conservation. Bird Conserva-tion International 5:251-277.

Howell, S.N.G., and S. Webb 1995. A guide to the birds of Mexico and northern Central America. Oxford University Press, New York.

[IUCN] International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2015. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015-4. Avail-able from <www.iucnredlist.org>.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1997. The Hummingbirds of North America, 2nd ed. Smithsonian Insti-tution Press, Washington, DC.

Lira, R., J.L. Villaseñor, and E. Ortíz. 2002. A proposal for the conservation of the family Cucurbitaceae in Mexico. Biodiversity and Conservation 11:1699-1720.

Mazariegos, O.Ch. 2010. Of birds and insects; The hummingbird myth in ancient Meso-america. Ancient Mesoamerica. 21:45-61.

McGuire, J.A., C.C. Witt, J.V. Remsen Jr., R. Dudley, and D.L. Altshuler. 2009. A higher level taxonomy for hummingbirds. Journal of Ornithology 150:155-165.

Miles L., A.C. Newton, R.S. DeFries, C. Ravil-ious, I. May, S. Blyth, V. Kapos, and J.E. Gordon. 2006. A global overview of the conservation status of tropical dry forests. Journal of Biogeography. 33:491-505.

Morrone, J.J. 2005. Hacia una síntesis bio-geográfica de México. Revista Mexicana de la Biodiversidad 76:207-252.

Navarro, A.G. 1992. Altitudinal distribution of birds in the Sierra Madre del Sur, Guerrero, Mexico. Condor 94:29-39.

Possingham, H.P., J. Day, M. Goldfinch, and F. Salzborn. 1993. The mathematics of

designing a network of protected areas for conservation. Pp. 536–545 in D. Sutton, E. Cousins, and C. Pierce, eds. Decision Scienc-es: Tools for Today. Proceedings of the 12th Australian Operations Research Conference, Australian Society for Operations Research, Adelaide, Australia.

Quesada M.G.A., M. Sánchez-Azofeifa, K. Alvarez-Anorve, L. Stoner, J. Avila-Caba-dilla, A. Calvo-Alvarado, M.M. Castillo, M. Espíritu-Santo, G.W. Fagundes, J. Fer-nandes, M. Gamon, D. Lopezaraiza-Mikel, P. Lawrence, J. Morellato, F. Powers, V. Neves, R. Rosas-Guerrero, R. Sayago, G. Sanchez-Montoya. 2009. Succession and management of tropical dry forests in the Americas: review and new perspectives. Forest Ecology and Management 258:1014-1024.

Rzedowski, J. 1978. Vegetación de México. Limusa. México D.F.

Schuchmann, K.L. 1999. Family Trochilidae (Hummingbirds). Pp. 468-680 in J. Del Hoyo, A. Elliot, and J. Sargatal, eds. Hand-book of the Birds of the World. Volume 5: Barn-owls to Hummingbirds. Lynx Editions, Barcelona, Spain.

SEMARNAT/CONANP. 2000. Plan de Mane-jo de la Reserva de la Biósfera Sierra de Manantlán. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México.

SEMARNAT/CONANP. 2001. Plan de Manejo de la Reserva de la Biósfera El Ocote. Diario Oficial de la Federación, México.

Toledo-Aceves, T., J. Meave, M. González-Es-pinosa, N. Ramírez-Marcial. 2011. Tropical montane cloud forests: Current threats and opportunities for their conservation and sustainable management in Mexico. Journal of Environmental Management. 92:974-981.

Villaseñor J.L., G. Ibarra, and D. Ocaña. 1998. Strategies for the conservation of Aster-aceae in Mexico. Conservation Biology 12:1066-1075.