How can we reach reluctant parents in childcare programmes?

Transcript of How can we reach reluctant parents in childcare programmes?

This article was downloaded by: [Northeastern University]On: 28 November 2014, At: 11:20Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Early Child Development and CarePublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gecd20

How can we reach reluctant parents inchildcare programmes?A. Mercedes Nalls a , Ronald L. Mullis a , Thomas A. Cornille a ,Ann K. Mullis a & Nari Jeter aa Florida State University , Tallahassee, USAPublished online: 02 Jul 2009.

To cite this article: A. Mercedes Nalls , Ronald L. Mullis , Thomas A. Cornille , Ann K. Mullis &Nari Jeter (2010) How can we reach reluctant parents in childcare programmes?, Early ChildDevelopment and Care, 180:8, 1053-1064, DOI: 10.1080/03004430902726040

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004430902726040

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoeveror howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to orarising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Early Child Development and CareVol. 180, No. 8, September 2010, 1053–1064

ISSN 0300-4430 print/ISSN 1476-8275 online© 2010 Taylor & FrancisDOI: 10.1080/03004430902726040http://www.informaworld.com

How can we reach reluctant parents in childcare programmes?

A. Mercedes Nalls*, Ronald L. Mullis, Thomas A. Cornille, Ann K. Mullis and Nari Jeter

Florida State University, Tallahassee, USATaylor and Francis LtdGECD_A_372774.sgm(Received October 2008; final version received April 2009)10.1080/03004430902726040Early Childhood Development and Care0300-4430 (print)/1476-8275 (online)Original Article2009Taylor & [email protected]

Young children benefit most from their experiences in childcare centres whentheir parents are actively involved in centre activities. However, childcareprofessionals sometimes face obstacles in engaging and maintaining cooperativeworking relationships with families. This is especially true for families that arehard to reach or families that are reluctant to develop or maintain such arelationship. This article provides childcare professionals with a framework forunderstanding various factors – both external and internal to families – whichmight impede the development of such a relationship. Further, the article describestechniques for working with different types of family patterns in ways thatincrease the likelihood of centres and families providing a nurturing environmentfor their children.

Keywords: childcare; parent involvement; parent–teacher relationship; familypatterns

How do we build strong parent–teacher relationships?

Children’s success in educational settings depends a great deal on family backgroundand parent involvement in the educational setting (Cohen, Ablow, Johnson, &Measelle, 2005; Epstein & Sanders, 2002). Honig (2002) noted that family back-ground works the way it does because of the things parents choose to do with theirchild and with the process of educating their child. For example, Endsley and Minish(1991) noted that communication between parents of children in childcareprogrammes and their caregivers were often adversarial and strained. They observedparent–staff communications over an extended period of time in childcare settings andfound that these communications lasted on an average about 12 seconds and werehighly perfunctory. In this case, parents were not engaged in connecting with theprogramme staff about their child nor were they taking the opportunity to participatefully in the educational experiences of their child.

There are many ways parents might become involved in their children’s education.Frequently, the form – parent involvement takes – is shaped by resources and oppor-tunities available to the parent (including those provided by the childcare programme),the relationship between the parent and the child, and the interest parents have in theeducation of their child. Families vary considerably in their resources and motivationsto become involved in their child’s early education. Some families served by childcare

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

1054 A.M. Nalls et al.

programmes are often overwhelmed by their own circumstances – whether economicor social – that may prevent them from participating in their child’s education experi-ences (Epstein & Sanders, 2002). In this case, childcare services that are oftenintended to ameliorate stressful life circumstances or at the least, offer professionalexpertise and developmentally appropriate childcare programming are less effective.Although most childcare providers report that they try to engage and work with theirparents they often find that their efforts do not result in parents becoming activelyinvolved in their children’s care and education (Epstein & Sanders, 2002; Hoover-Dempsey, Walker, Jones, & Reed, 2002; Mullis, Mullis, & Cornille, 2005; Weiss,Kreider, Lopez, & Chapman, 2005). Cornille et al. (2005) noted that childcareprofessionals do not have effective strategies for identifying characteristics of hardto reach and reluctant families served by childcare programmes, nor do they haveeffective models for helping parents become more involved in fully utilising childcareservices. This initial stage of recognition could then provide a framework forintervention strategies to reduce families’ reluctance and enhance collaborative rela-tionships between the families and childcare professionals. This article provides asynthesis of responses of childcare professionals regarding issues related to engaginghard to reach families, a typology for understanding patterns of family disconnectionfrom services and a model for recognising and intervening with various types offamilies.

Experiences of childcare providers

Mullis et al. (2005) surveyed childcare professionals about their duties and responsi-bilities within the childcare setting. These responses included a range of duties andresponsibilities, including programme administration, professional and programmedevelopment, staff supervision, budgeting, grant writing, programme meetings,community outreach, advocacy and phone and in-person contact with clients. Theseprofessionals also detailed characteristics of families they had experienced as being atrisk (Schlee, Shriner, Byno, Berarducci, & Mullis, 2005). These risk factors includedpoverty and financial stresses, physical and social isolation, cultural and languagebarriers, feelings of frustration, shame and embarrassment, unrealistic expectations ofresources, family crises and special needs of the children or family. The respondentsalso were asked to detail strategies they utilised in response to perceived reluctancefrom families. The childcare professionals indicated that they used several strategiesor techniques to engage reluctant families in the referral process; including offeringinformation, mailings, telephone calls, encouraging relationship building with andactively listening to clients, assessing family needs, making referrals to relevantresource agencies, being understanding of family crises and implementing culturallysensitive techniques or strategies.

Childcare professionals have often been encouraged to identify parent involve-ment models to assist them in developing and articulating useful strategies forworking with hard to reach and reluctant families (Cohen et al., 2005; Schneider &Coleman, 1993). For example, Cornille et al. (2005) observed that parents in a varietyof community settings benefited from quality childcare services when individual andcontextual barriers hindering families from fully utilising childcare services werereduced. This initial stage of recognition could then provide a framework for interven-tion strategies to reduce families’ reluctance and enhance collaborative relationshipsbetween the families and childcare professionals. This article provides a model for

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

Early Child Development and Care 1055

recognising and intervening with various types of families and a typology for under-standing patterns of family disconnection from services in their communities.

Contextual focus of parent involvement

Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) suggest that children develop in a complexnetwork of interacting systems, which can include families, neighbourhoods, schools,work, or childcare programmes to name a few. None of these systems have sole influ-ence on the child and as anyone who cares for children knows, the child influences thelarger system as well. Families develop patterns of living in the context of their largersystems and they provide the context for the child’s primary experience of the world.Similarly, childcare centres provide another context for the child. In the family’s inter-actions with centre staff, a process unfolds that addresses the fit between those twocontexts’ patterns and how well they support the child’s development.

The relationship between parents and childcare professionals can enhance theresilience of the family. There is growing recognition that resilience is multi-determined and multi-dimensional and it must be considered within the context ofmultiple system levels over time (Walsh, 1996, 2006). As part of this understanding,negative and positive characteristics of the individual, family and community can beidentified (Walsh, 2002). These factors have been classified as risk and protectivefactors, respectively. Risk and protective factors may be biological, psychological,social, economical, spiritual, cultural and environmental (Waller, 2001). Risk andprotective factors are not rigid, but dynamically changing (Hawley & DeHaan, 1996).Furthermore, what may be recognised as a risk factor in one crisis may be labelled aprotective factor in another situation (Hawley & DeHaan, 1996; Waller, 2001) Also,the relative strength of a risk or protective factor may vary according to the eco-systemic context and the nature of the crisis. Given the complexity of risk and protec-tive factors, the eco-systemic context and the relevance of time and developmentalfactors, no one coping strategy or mechanism is more effective or successful thananother (Walsh, 1996, 2006).

A good childcare centre, where strong relationships are built between childcareprofessionals and families can serve as an important protective factor. This relation-ship can serve as a buffer against many of the risk factors found in the multiplecontexts within which families live and work. In this case, childcare professionals andfamilies who discover the shared goal of nurturing and educating children and developways of working together toward this goal benefit children directly.

Family patterns

Before exploring the range of styles that families exhibit when interacting withchildcare professionals, it is useful to first recognise that there are families who viewthemselves as active participants in partnership with the childcare centre. These fami-lies, as we will discuss later, can be a challenge to work with because they bring theirown set of values and goals for their children that may not readily fit with the predict-able patterns of childcare centres. These families are not hard to reach or reluctant.Instead they will actively seek out opportunities to be involved with their children andtheir children’s providers. However, this does not mean that these families will simplycomply with the routines that are set up by the centre. As we will review in the‘Family Distress and Outreach models’ (Cornille & Boroto, 1992), these actively

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

1056 A.M. Nalls et al.

engaged families require the same level of skill on the part of the childcareprofessional as do families that are hard to reach or reluctant.

Hard to reach families are described as families that find interacting with othersocial systems challenging because of social or demographic issues other than familypatterns (Cornille et al., 2005). These families are contending with many of theindividual, family and community risk factors previously discussed. Generally, hardto reach families are those who want and/or need assistance that does not readily fitwithin the design of childcare service programmes. Social barriers can exist for hardto reach families for a number of reasons. For example, time constraints due to workschedules, geographical access to the centres because of limitations of public orprivate transportation and language barriers can all interfere with families being ableto participate fully in the family aspects of a childcare programme, such as open-houses or other programmes that are meant to bring families together.

For example, families that have migrated to the USA can find the structure andpatterns of social agencies and schools to be confusing and daunting, regardless ofwhether English is the first language. If English is not the first language, the issues ofunderstanding either written or spoken communications can potentially complicate thedifferences across cultures. The solution for one school was for a volunteer to translatewritten communications, such as newsletters and academic calendars into the nativelanguage of the family (Her, 2004).

Reluctant families are those families whose patterns of dealing with outsidesystems are influenced by how they handle existing problems or crises in the family(Cornille et al., 2005). Hard to reach families are difficult families for childcareprofessionals because of specific social or demographic barriers, just as the name indi-cates. On the other hand, reluctant families are difficult families because of how theyperceive outside help while they are resolving problems and maintaining equilibrium.This will be discussed in more depth later in the article. The next section will describetwo kinds of professional roles in working with families and the five kinds of familypatterns (one of which is a reluctant pattern) and ways that those patterns can affecthow the childcare programme can successfully engage such families.

Professional roles

Before working through the Family Distress and Outreach models, we want to firstexplain how the two types of professional roles influence conversations betweenfamilies and professionals. Directive relationships are based on the premise that theprofessional brings expertise to the relationship, evaluates the needs and issues facedby the family, prescribes a course of action to be followed and the family (if cooper-ative) makes successful adaptation of the previous patterns to a new mode of acting.A good example is when a childcare professional finds that a child is showing signsof a developmental delay. As an expert in the development of young children, thechildcare professional advises the family to take the child to their primary careprovider or specialist for a diagnosis. In this case the childcare professional is actingin a directive manner.

Families that work with a professional who is using a collaborative approachexperience a different style of relating. The professional works with the family toexplore and discuss the current situation, helping them to become aware of theirgoals and options and then the family decides which course to take. For instance, if achild is having a difficult time adjusting to a centre (e.g. becoming inconsolable after

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

Early Child Development and Care 1057

being left by the parent), using a collaborative approach, the childcare professionalasks the family what they think are some possible solutions. Depending on the goalsor flexibility of the family’s schedule, various alternatives may be a possibility, suchas having a parent spend part of the day with the child at the centre or seeing ifthe child would respond better to being cared for by a relative. The childcare profes-sional helps the family to explore potential solutions and supports the family’sdecisions.

Both approaches have value and in fact we believe that when families are met withan approach that does not match with what they want and need, the results will be lessthan helpful. In the next section, we will describe how child care professionals canmatch the style of relating to the family with the phase that the family is experiencingto better serve the family and increase the likelihood that the professional will have apositive experience.

The Family Distress and Outreach models

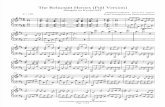

The Family Distress Model (see Figure 1) is a theoretical framework that promotesunderstanding families patterns in their relationships with school systems (Cornille &Boroto, 1992; Cornille, Boroto, Barnes, & Hall, 1996). The Family Distress Modelexplores from a non-pathology based perspective the ways that families may deal withdaily living and problems. The model is primarily based upon research of familypatterns of predictability (Reiss, Gonzalez, & Kramer, 1986; Steinglass, Bennett,Wolin, & Reiss, 1987) and social support (House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988). TheFamily Distress Model identifies five phases in family dynamics that childcareprofessionals can identify in order to more clearly determine how to interact with suchfamilies.Figure 1 The Family Distress Model.When childcare professionals apply the Family Distress Model (see Figure 1) totheir interactions with a family, there are five questions to answer in determining howto best help the family: (1) In what stage is this family? (2) What does this family want(not need) from the professional? (3) Which style of professional relationship(directive or collaborative) will best support what the family wants? (4) What is thegoal for the overall relationship? (5) What tools might I use presently to facilitatemovement toward that goal? The questions and possible tools for each stage areprovided in the Family Outreach Model (See Table 1).

Central to the Family Outreach Model is the recognition that the patterns of work-ing relationships contribute powerfully to the outcome of those relationships.Research on the working relationship or therapeutical relationships has documentedthat the quality of that relationship is predictive of outcomes across a wide range ofhelping relationships (Bachelor & Horvath, 1999). In addition to the quality of thehelping relationship contributing to outcomes, the style of that relationship contrib-utes to overall quality and therefore needs to utilise intentionally (Gutkin, 1999).Directive relationships are grounded in an expert stance where the role of the profes-sional is responsible for evaluating the situation and prescribing a course of actionand the role of the client/patient is to adapt their actions to comply with the prescrip-tion. On the other extreme, the role of a professional in a collaborative relationship isto assist the client/patient with a description of the situation, support the developmentof awareness of alternatives and the primary role of the client is make informedchoices about the course of action to take (Cornille, Meyer, Mullis, Mullis, & Boroto,2008).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

1058 A.M. Nalls et al.

Phase 1

Families in Phase 1 organise their lives around beliefs and values that they believeaffect the family’s well-being. From those beliefs and values, families developpredictable patterns and strategies for coping with problems that can be recognised

Figure 1 The Family Distress Model.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

Early Child Development and Care 1059

Tabl

e 1.

The

Fam

ily O

utre

ach

Mod

el i

n ch

ildc

are

sett

ings

.

Que

stio

ns a

nd

stra

tegi

esP

hase

1P

hase

2P

hase

3P

hase

4P

hase

5

In w

hat

Pha

se i

s th

e fa

mil

y?T

he f

amil

y ha

s es

tabl

ishe

d pr

edic

tabl

e pa

tter

ns

and

thes

e pa

tter

ns a

re

supp

orti

ng t

he

fam

ily’

s vi

sion

of

itse

lf a

nd i

ts g

oals

.

The

fam

ily

is d

eali

ng

wit

h a

disr

upti

on i

n pr

edic

tabl

e pa

tter

ns

and

is m

anag

ing

the

upse

t usi

ng th

e to

ols

it

has

sele

cted

.

The

fam

ily

is d

eali

ng

wit

h a

maj

or

disr

upti

on t

hat

the

fam

ily

is u

nabl

e to

re

solv

e us

ing

its

typi

cal

stra

tegi

es.

The

fam

ily

has

deal

t w

ith

a cr

isis

and

not

so

lved

it

and

now

is

aski

ng f

or o

utsi

de

help

.

The

fam

ily

is o

rgan

ized

ar

ound

an

earl

ier

cris

is.

The

pat

tern

s be

ing

used

no

w a

re m

eant

to

keep

is

sues

and

out

side

rs

unde

r co

ntro

l.

Wha

t do

es t

he

fam

ily

wan

t?T

he f

amil

y se

eks

cont

acts

wit

h ot

her

syst

ems

to s

uppo

rt i

ts

patt

erns

and

goa

ls,

e.g.

a c

hild

care

cen

tre

who

se s

ched

ule

fits

th

at o

f th

e fa

mil

y.

The

fam

ily

mig

ht b

e se

ekin

g so

luti

ons

or

info

rmat

ion

from

ou

tsid

ers,

e.g

. wan

ting

in

form

atio

n ab

out

chil

dcar

e in

a n

ew

com

mun

ity.

The

fam

ily

feel

s ov

erw

helm

ed a

nd

need

s so

meo

ne e

lse

to p

rovi

de d

irec

tion

ou

t of

the

cri

sis,

he

lp t

o ge

t aw

ay

from

hur

rica

ne.

The

fam

ily

is f

acin

g ag

ain

the

cris

is a

nd is

as

king

for

ass

ista

nce

to r

esol

ve i

t, ho

w t

o he

lp a

chi

ld r

e-en

ter

a ce

ntre

aft

er a

lif

e-th

reat

enin

g in

jury

.

The

fam

ily

is f

earf

ul t

hat

outs

ider

s w

ill

be

judg

emen

tal

of t

heir

si

tuat

ion.

The

y w

ant

supp

ort

to c

onti

nue

doin

g w

hat

they

are

do

ing.

Wha

t st

yle

of

rela

tion

ship

bes

t su

ppor

ts t

he

fam

ily

gett

ing

wha

t it

wan

ts?

Col

labo

rati

ve

part

ners

hip

Col

labo

rati

ve p

artn

ersh

ipE

xper

t gu

idan

ceE

xper

t gu

idan

ce i

n a

coll

abor

ativ

e pa

rtne

rshi

p

Col

labo

rati

ve p

artn

ersh

ip

Wha

t is

the

goal

of

the

rela

tion

ship

be

yond

wha

t the

fa

mil

y w

ants

?

To

assi

st t

he f

amil

y to

m

ake

use

of

com

mun

ity

reso

urce

s th

at f

it w

ith

the

goal

s of

the

fam

ily.

To

supp

ort

the

fam

ily

in

reso

lvin

g th

e pr

oble

m

by m

akin

g us

e of

eit

her

fam

ily

or c

omm

unit

y re

sour

ces.

To

guid

e th

e fa

mil

y th

roug

h th

e cr

isis

an

d he

lp i

t to

re-

esta

blis

h pr

edic

tabl

e pa

tter

ns (

eith

er o

ld

or n

ew o

nes)

.

Gui

de t

he f

amil

y to

war

ds i

ts d

esir

ed

goal

s an

d re

linq

uish

di

rect

ion

to

coll

abor

atio

n as

soo

n as

pos

sibl

e.

To

dem

onst

rate

sup

port

for

the

fam

ily

and

rem

ind

it

that

pro

fess

iona

ls a

re

avai

labl

e to

hel

p, i

f th

e fa

mil

y w

ants

.

Wha

t to

ols

can

I us

e to

fac

ilit

ate

mov

emen

t to

war

ds t

he

goal

?

Mak

e ex

plic

it t

he g

oals

, va

lues

and

pat

tern

s th

at y

our

cent

re h

as

and

exam

ine

how

wel

l th

e go

als

and

patt

erns

of

the

cen

tre

and

fam

ily

fit

toge

ther

.

Exp

lore

wha

t th

e fa

mil

y de

fine

s as

the

prob

lem

an

d w

hat s

trat

egie

s it

is

usin

g to

sol

ve it

. Som

e fa

mil

ies

wan

t to

sha

re

dist

ress

, and

do

not

wan

t ou

tsid

e so

luti

ons.

Acc

ess

to e

mer

genc

y re

sour

ces

in t

he

com

mun

ity.

Pro

vide

li

nks

betw

een

fam

ily

and

emer

genc

y se

rvic

es,

e.g.

Red

Cro

ss.

Hel

p th

e fa

mil

y to

re

cogn

ize

how

it

is

shif

ting

fro

m c

risi

s m

ode

to s

elf-

dire

ctio

n m

ode.

Be

read

y to

giv

e up

di

rect

ion.

Ask

how

the

fam

ily

wou

ld

know

that

it is

rea

dy f

or

outs

ide

help

. Lea

rn w

hat

the

fam

ily

is d

oing

now

to

cop

e, e

.g. d

oes

the

pare

nt tr

y to

con

trol

and

pr

even

t an

y di

srup

tion

s?

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

1060 A.M. Nalls et al.

both by the family and by outsiders who come in contact with the family. The predict-able patterns can be grouped into several different themes that interact and are semi-independent of one another. These themes (The five R’s) include: roles, rules,routines, rituals and relationships with outsiders. Each of these patterns reflects thecurrent goals and values of the family. For example, a family who is committed tofamily security might select a centre that appears more secure than another thatappears to be less restrictive and more open to outsiders.

Outreach

With Phase 1 families, a collaborative relationship naturally develops as a childcareprofessional becomes acquainted with a family learning about their background,beliefs, or desires for their child’s development. The result of such consultations isthat the childcare professional will have a description of the family’s wants and needsthat the family has supplied. Likewise, the childcare professional should know andshare with the family the centre’s mission and values.

Also, a childcare professional should ascertain whether there are any potential riskfactors or social/demographic barriers that would make this family a hard to reachfamily. For instance, it would be important for a childcare professional to know thatthe child’s grandparents, who speak only Chinese, will be dropping off and picking upthe child while the parents work. Understanding the family’s barriers as well as goalswill help the childcare professional develop successful patterns in working with thefamily. Instead of trying to communicate with the child’s grandparents when theyarrive, notes or evening phone calls may have to be arranged in order to reach thechild’s parents. A childcare professional’s goal with Phase 1 families is to determinehow the centre best fits into the family’s current patterns (the five R’s).

Phase 2

Phase 2 is marked by the occurrence of a problem, which is any disruption of thefamily’s established patterns, beliefs, or values. Problems do not require that thefamily perceive the situation as a negative event. Having a child out of the childcarecentre because of a holiday or because the child is ill can trigger the same strategies(roles, rules, routines, rituals and relationships with outsiders) for re-establishingbalance in the family. When a problem or disruption occurs, families will adapt estab-lished ways of problem solving and attempt to restore predictability. Some familiesdiscuss options and make a rational decision; other families put one family member incharge of dealing with the issue, while the rest of the family carries on with life asusual. Some families will argue with one another and even outsiders as a way of clar-ifying what they want to do. Regardless of the strategy, the goal of the family is thesame; to help the family to return to a state of equilibrium. In the instance where thechild is ill or out for a holiday, the family’s prior solution to similar problems is for aparent to take a sick day from work.

Outreach

In most cases, a collaborative partnership produces the best results for both the familyand the childcare professional. In Phase 2 where the family may be seeking solutions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

Early Child Development and Care 1061

and attempting to use established patterns to resolve the problem, a collaborative part-nership would make the family aware of its options so that it can make an informeddecision. For instance, the work schedule of one of the parents may have suddenlychanged making the current childcare centre schedule inconvenient. The family mayneed to find another childcare centre that offers extended hours or an alternativesolution to the problem. A childcare professional would need to explore what thefamily defines as the problem and identify what the family wants. The goal of thecollaborative partnership in this case would be to assist the family in finding a newchildcare centre that is a better fit for the family’s schedule or to identify anotherpossible community or family resource.

In Phase 2, the family would rely on already established patterns of behaviour. Forinstance, the mother may take her lunch break to pick up the child when the childcarecentre closes or have another relative or ‘family friend’ help. The family has usedthese options before to resolve problems in the past. Therefore, at this stage, the familystill believes it can resolve its own issues and looks to the childcare professional forinformation and support. A collaborative partnership helps the family to be aware ofall of its options, where as a directive approach may alienate and isolate the childcareprofessional from the family.

Phase 3

Phase 3 occurs when strategies typically used to solve problems are exhausted and thefamily fails to resolve the disruption, causing a crisis. Within this conceptual model,problems and crises are distinguished by the availability of strategies for resolutionrather than the intensity of emotional experience or response that the family expresses.Thus, families are not viewed as being in crisis because of the external event, butrather because of how well their coping strategies fit the event.

An example of a crisis is when a child has been chronically ill throughout the yearand the parents have used all leave from work. Using sick or vacation leave to care forthe child had been the family’s routine solution to the problem. However, when thisoption is exhausted the family will experience a crisis. Obviously, families will notremain in this phase any longer than absolutely necessary and will choose to eitheraccept or reject those offering support.

Outreach

If the problem has become a crisis and the family, now in Phase 3, has attempted tohandle the crisis but is completely overwhelmed, the childcare professional shouldtake a more directive approach in supporting the family. Regarding the example withthe child who has experienced repeated illnesses, a directive approach would includethe childcare professional recommending specific services that would help the family,such as daycare or respite services that are better able to meet the family and child’sneeds.

Another good example of this would include if the family’s home was destroyedby a tornado. The family may have seen their pre-existing strategies fail, such as rely-ing on relatives or friends for support. The childcare professional should take a moredirective approach and guide the family by helping them access the emergencyresources in the community. A hard to reach family may need extra help completingforms or communicating with other service providers.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

1062 A.M. Nalls et al.

Phase 4

In Phase 4, the family becomes organised around the crisis. Often, the crisis iscontained within the family system as the family attempts to develop new predictablepatterns exclusive of relationships with outsiders. As the family believes they aremanaging the crisis adequately, distress occurs when an outsider attempts to assist thefamily in problem solving. In this isolated position, the family tries to reach a level ofequilibrium, in spite of having to contend with a situation that is beyond their strate-gies. In other words, they have already tried to use their coping strategies and they didnot solve the problem. Now they face the crisis and try to use tools from a differentphase – they try to use predictable patterns (the five Rs) to re-establish predictability.They will develop a routine to deal with the crisis, set up roles to manage the crisisand have rules that are shaped by the crisis. Unfortunately, these families are dealingwith the situation in isolation and can also be called reluctant families because of theirrefusal to seek outside help.

For instance, the family with the chronically ill child that has exhausted their sickleaves continues to attempt to solve the crisis with previous strategies and haverefused to follow any of the childcare professional recommendations. A new patternis established where one of the parents takes the child to work in order to manage thechild’s medication needs. This solution most likely is only temporary.

Outreach

Frequently a family in Phase 4 may choose to handle a crisis by withdrawing fromthose who offer support. For instance, a child in your childcare centre may have beendiagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder and needs specific developmental thera-pies. The family may be isolating itself from seemingly judgemental outsiders. Acollaborative approach is ideal with families in this phase, allowing the family todescribe their wants and possible options that would meet their wants and needs. Thechildcare professional should support the family by making them aware that supportservices are available when they need them.

Phase 5

In the fifth phase, the family begins using support to resolve the crisis. When outsidersare perceived as supportive and not judgemental, the family can maximise usage ofthe goods and services that will help them to re-connect with their core values andgoals and re-establish new predictable patterns. As families are given support andresponsibility for accessing their needed services, they will become more active in allareas of their lives (Coffey, 2004). Once families re-establish new predictable patternsor return to their old patterns, they return to Phase 1.

For instance, the family with the child who needs medical or developmental ther-apies moves into Phase 5 when they realise that they need outside support. The familycan resolve its crisis by accepting help and adapting to the suggestions of the childcareprofessional. A new pattern is created that involves this added dimension of support.

Outreach

A family in Phase 5 recognises that it needs outside help in order to resolve the crisisand will seek out the childcare professional for expert guidance. In the case of the

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

Early Child Development and Care 1063

child who has been diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, the childcareprofessional should at first direct the family to the appropriate community resourcessuch as centres that offer special education classes or support groups for the family.The childcare professional moves from a directive to a collaborative partnership. Thecollaborative relationship develops by helping the family to become more independentand self-directive in establishing new predictable patterns for handling the crisis.

Summary and conclusions

In summary, developing and maintaining working relationships with families fromdiverse backgrounds is a daily challenge that childcare professionals face. In addition,families at times are dealing with the pileup of stressful events that they deal with bywithdrawing from potential support and becoming organised around those situations.Working with either hard to reach or reluctant families requires a unique perspectiveand skills.

From a contextual perspective, the interactions in the childcare setting play animportant role in a family’s life and the children who participate there. This article hasprovided professionals with a model for understanding family responses to distressingsituations and tools for engaging and maintaining relationships with those families.Therefore, childcare professionals should endeavour to combat any potential riskfactors and become one of the protective factors in the family’s life. Much of the child-care professional’s time is reported as being spent reaching out and trying to understandthe various family situations and crises. This task would be facilitated by a better under-standing of the different types of families, the ways a family processes disruptions andthe best techniques to help families in the midst of a wide range of stressful experiences.

Notes on contributorsA. Mercedes Nalls is a doctoral student in the Department of Family and Child Sciences atFlorida State University.

Ronald L. Mullis is a professor of family and child sciences at Florida State University.

Thomas A. Cornille is an associate professor in the Department of Family and Child Sciencesat Florida State University.

Ann K. Mullis is an associate professor in the Department of Family and Child Sciences atFlorida State University.

Nari Jeter is an adjunct professor at Florida State University.

ReferencesBachelor, A., & Horvath, A. (1999). The therapeutic relationship. In M.A. Hubble, B.L.

Duncan, & S.D. Miller (Eds.), The heart and soul of change (pp. 133–178). Washington,DC: American Psychological Association.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P.A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development.In W. Damon & R.M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoreticalmodels of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Coffey, E.P. (2004). The heart of the matter 2: Integration of eco-systemic family therapypractices with systems of care mental health services for children and families. FamilyProcess, 2, 161–173.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014

1064 A.M. Nalls et al.

Cohen, P.A., Ablow, J.C., Johnson, V.K., & Measelle, J.R. (2005). The family context ofparenting in children’s adaptation to elementary school. Mahwah, NJ: LawrenceErlbaum.

Cornille, T., & Boroto, D. (1992). The family distress model: A theoretical and clinical appli-cation of Reiss’ close families findings. Contemporary Family Therapy, 14(3), 181–198.

Cornille, T., Boroto, D., Barnes, M., & Hall, P. (1996). Dealing with family distress inschools. Families in Society, 77(7), 435–445.

Cornille, T.A., Meyer, A.S., Mullis, A.K., Mullis, R.L., & Boroto, D. (2008). Tools for engag-ing and working with families in distress. Journal of Family Social Work, 11, 185–201.

Cornille, T., Mullis, R., Mullis, A., Berarducci, N., Shriner, M., & Byno, L. (2005, Novem-ber). Engaging reluctant families in family services. Paper presented at the annual confer-ence of the National Council on Family Relations, Phoenix, AZ.

Endsley, R.C., & Minish, P.A. (1991). Parent–staff communication in day care centres duringmorning and afternoon transitions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 6, 119–135.

Epstein, J.L., & Sanders, M.G. (2002). Family, school and community partnerships. In M.H.Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 5. Practical issues in parenting (pp. 407–437). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gutkin, T.B. (1999). Collaborative versus directive/prescriptive/expert school-based consulta-tion: Reviewing and resolving a false dichotomy. Journal of School Psychology, 37(2),161–190.

Hawley, D.R., & DeHaan, L. (1996). Toward a definition of family resilience: Integratinglife-span and family perspectives. Family Process, 35(3), 283–298.

Her, L. (2004). Reaching out to Hmong families: National Network of Partnership Schools.Retrieved September 14, 2005, from http://www.csos.jhu.edu/p2000/PPP/2004/pdf/70.pdf

Honig, A.S. (2002). Choosing childcare for young children. In M.H. Bornstein (Ed.),Handbook of parenting (pp. 375–405). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hoover-Dempsey, K.V., Walker, J.M.T., Jones, K.P., & Reed, R.P. (2002). Teachings involv-ing parents (TIP): Results of an in-service teacher education program for enhancing paren-tal involvement. Teacher and Teaching Education, 18, 843–867.

House, J.S., Umberson, D., & Landis, K.R. (1988). Structures and prcesses of social support.Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 293–318.

Mullis, A.K., Mullis, R.L., & Cornille, T.A. (2005, March). Engaging reluctant and hard toreach families: Intervention research lessons. Paper presented at the annual meeting ofthe National Association of Childcare Resource and Referral Agencies. Washington, DC.

Reiss, D., Gonzalez, S., & Kramer, N. (1986). Family process, chronic illness, and death: Onweakness of strong bonds. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43, 795–804.

Schlee, B., Shriner, M., Byno, L., Berarducci, N., & Mullis, A. (2005, July). Early readingskills for pre-schoolers: How can parents and teachers make a difference? Paperpresented at the One Goal summer conference on One Goal: Building the Future Together‘Putting Families and Children First’, Tampa, FL.

Schneider, B.S., & Coleman, J.C. (1993). Parents, their children and schools. Boulder, CO:Westview Press.

Steinglass, P., Bennett, L., Wolin, S., & Reiss, D. (1987). The alcoholic family. New York:Basic Books.

Waller, M.A. (2001). Resilience in eco-systemic context: Evolution of the concept. AmericanJournal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(3), 290–297.

Walsh, F. (1996). The concept of family resilience: Crisis and challenge. Family Process,35(3), 261–281.

Walsh, F. (2002). A family resilience framework: Innovative practice applications. FamilyRelations, 51(2), 130–137.

Walsh, F. (2006). Strengthening family resilience (2nd ed.). New York: Guildford Press.Weiss, H.B., Kreider, H., Lopez, M.E., & Chapman, C. (Eds.). (2005). Preparing educators to

involve families: From theory to practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

thea

ster

n U

nive

rsity

] at

11:

20 2

8 N

ovem

ber

2014