H'IIhwa~, oo~e

Transcript of H'IIhwa~, oo~e

REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form ApprovedOMS No, 0704-0188

TM pu~l", r"JlO<''''II tlurdo" lor l~i. co~"""on 01 iofonn..i"" i' ".,Imated t. av"rol/O 1 ""'" p.r r."po".., 'r><:luding tM ''''''' for """"""9 ""UlI<t,,,,,,,. ,oorolbng ••io"ng d..o OOUfoe"gothe,,"lI ond """'O'n11'1g the do'o n..dod,...,d comple,,"lI and re.iowi"ll the collec""" of .,formotlon, Send commen" regarding ,til, ....d..., ."t,m.,.".. Iny other ",ooct of th,,, collection of.,formoti"". ,ncIYd,"lI .uW."""" lor roduc,"lI tho bur""", to Deportment of Del..,... Wo,h"'ll1Of1 Heod""o"e,. ServICeo, D....to..t" for fnl.",....,,,,, ",,",a"on, and R,,1XI"0 ID704·Q1861.'215 Jelt",,,,,.., Dav" H'IIhwa~, Sulto 1204. A,hng'<>n. VA 22202·4302. lIe.pOndo".. 'hould be awar. thot notwlth",and.,g any O'ho' pro.,.oon of law, no oorso" ,holl be .vbj...,t to onyoo"""v f'" foil;"'g to comply wi'h 0 oo~e<tOO" of ""f"'mot'".., jf" d".. not dlSplav a ou"e"tly .alid OMS 0""'''01 num~",.

PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS.1. REPORT DATE IDD-MM-YYYY! I' REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - ToJ

29-07-2009 Journal Article 2008 - 20094. TiTlE AND SUBTiTlE 5•. CONTRACT NUMBER

Iron Deficiency and Obesity: The Contribution of Inflammation andDiminished [ron Absorption 5b. GRANT NUMBER

5,. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER

,. AUTHOR(Sl Sd. PROJECT NUMBERJames P. McClung and James P. Karl

5•. TASK NUMBER

Sf. WORK UNIT NUMBER

7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) ,. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION

U.S. AmlY Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, MA 01760-5007REPORT NUMBER

MISC09-04

,. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAMEIS) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSOR/MONITOR'S ACRONYM(S)

U.S Army Medical Research and Material CommandFort DetrickFrederick, MD 21702-5012 ". SPONSOR/MONITOR'S REPORT

NUMBER(S)

1Z. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Approved for public release.Distribution is unlimitcd,

13. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES

14. ABSTRACT

Poor iron status alTects billions of people worldwide. The prcvalence of obesity continues to rise in both developed and developingnations. An association between iron status and obesity has been described in children and adults. The mechanism explaining thisrelationship remains unknown; however, findings from recent reports suggest that body mass index and inflammation predict ironabsorption and affect the response to iron fortification. The relationship between inflammation and iron absorption may be mediatedby hepcidin, although further studies will be required to confinn this potential physiological explanation for the increasedprevalence of iron deficiency in the obese.

15. SUBJECT TERMS

Hepcidin, inflammation, iron, obesity

LIMITATION OF 18. NUMBER16. SECURITY CLASSIFICATtON OF: 17. 19a. NAME OF RESPONSIBLE PERSON.. REPORT b. ABSTRACT c. THIS PAGE ABSTRACT OF Douglas DauphineePAGES

Unclassified Unclassified Unclassi tied UL 19b. TELEPHONE NUMBER (Include area code)4 508-233-4859

Standard Form 298 IRev. 8/98)Pro.o,il>o<l by ANSI Std. Z39.18

Emerging Science

Iron deficiency and obesity: the contribution of inflammationand diminished iron absorption

James P McClung and J Philip Karl

Poor iron status affects billions of people worldwide. The prevalence of obesitycontinues to rise in both developed and developing nations. An association betweeniron status and obesity has been described in children and adults. The mechanismexplaining this relationship remains unknown; however, findings from recentreports suggest thot bodymass index and inflammation predict iron absorption andaffect the response to iron fortification. The relationship between inflammation andiron absorption may be mediated by hepcidin, although further studies will berequired to confirm this potential physiological explanation for the increasedprevalence of iron deficiency in the obese.02009 Internalionallife Sciences Institute

INTRODUCTION

Iron is a nutritionally essential trace clement that is critical for optimal physical and cognitive performance.Despite advances in the nutritional sciences and thedevelopment of worldwide economies, iron defICiency

continues to be the most prevalent single micronutrientdeficiency disease in the world, affecting billions ofpeople.l The development of iron deficiency occurs instages, beginning with the depletion of iron stores,followed by diminished iron transport, and finally thedepletion of iron-containing proteins and enzymes,including hemoglobin, which results in iron deficiencyanemia. The consequences of iron deficiency anemiaare well described and include fatigue and diminishedwork capacity?·) The consequences of iron deficiencywithout anemia are not as well described, but likelyinclude diminished cognitive function and exerciseperformance.H In developed nations, iron defICiency andiron defICicncy anemia tcnd to affect premenopausalwomcn/ mainly through suboptimal iron intake andmenstrual iron losses. In contrast, in developing nations,poor iron status occurs in most all population demographics, typically due to the lack of foods containingbioavailable iron.

Until recently, few studies had considered bodyweight or body composition as factors related to irondeficiency. Interestingly, a recent study, using data fromthe third National Health and Nutrition ExaminationSurvey (NHANES III), determined that overweightAmerican children were twice as likely to be iron deficient than normal-weight children,S and similar findingshave since been reported in adults. 9 The associationbetween iron status and obesity is one that should beexplored further, as obesity and iron deficiency arc diseases that continue to evolve worldwide, and both havesignificant public health implications.

THE OBESITY EPIDEMIC

Obesity is a disease defined by an excess accumulation ofbody fat to the extent that health is adversely affected. Ie

Within only a few decades, obesity has become a globalpublic health concern. In the United States (US), thecountry for which the most comprchensive data is available, the prevalence of obesity has doubled over the pastthree decades;ll data from 2005-2006 indicate thatapproximately 34% of US adults are obese.12 The obesityepidemic is not limited to the United States; the

Affiliations: iP McClung and iP Karl are with the Military Nutrition Division, U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine(USARIEM), Natick, Massachussetts. USA.

Correspondence: lP MC(/lIng, Military Nlitrition Division, U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine (USARIEM), Natick,Massachussetts, MA 01760, USA. E-mail: James,[email protected], Phone: +1-508-233-4979, Fax: +1-508-233-4869.

Key words: hepcidin, inflammation. iron, obesity

doi, 10.1111/j.17S3-4887.2008,(l(114S.x100 Nutrition Reviews- Vol. 67(2):100~ 104

prevalence of obesity is increasing in all regions of theworld. 'o in 2005, an estimated 400 million adults worldwide were obese. lJ Furthermore, the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity is increasing, with theworldwide prevalence having doubled or tripled in industrialized countries over the past few decades.'~ The sametrends have been observed in developing countries. Forexample, the prevalence of adolescent and childhoodovenveight and obesity in children living in Egypt, Brazil,and Mexico has reached levels comparable to those seenin industrialized nations. H By 2010 an estimated one inseven children in the Americas and one in ten in theEastern Mediterranean and European regions arc predicted to be obese.1<

With approximately one half of ovenveight adolescents and one third of children carrying excess weightinto adulthood, IS the global epidemic of obesity will continue to worsen. The public health implications of theobesity epidemic are staggering; obesity is associated withincreased mortality from cardiovascular disease, diabetes,kidney disease, and some cancers. 16 In the United Statesalone, obesity was associated with 117 billion dollars indirect and indirect healthcare costs in 2000, and was thesecond leading cause of preventable death. '7

MAKING THE CONNECTiON

The first reports of a potential connection between ironstatus and obesity appeared over 40 years ago. IS

•19 These

reports described lower serum iron concentrations inobese as compared to normal-weight adolescents. Veryfew studies pursued the reported connection betweeniron status and obesity until recently, when a series ofinvestigations described an increased prevalence of irondeficiency in overweight and obese populations. The firstof these, a cross-sectional study published in 2003,described a greater prevalence of iron defiCiency, as indicated by serum iron levels <8IlmoI/L, in overweight andobese Israeli children and adolescents. lO Subsequently, alarge study using data from the National Health andExamination Survey (NHANES III) confirmed thosefindings using multivariate regression analyses to demonstrate that ovenveight American children were twice aslikely to be iron deficient than nonnal-weight controlchildren.' In this study, iron deficiency was determinedusing a three-variable model, including cui-off values fortransferrin saturation, free erythrocyte protoporphyrin,and serum ferritin.

The observations of a connection between ironstatus and obesity have since been extended to adults.Lecube et al. 9 reported that obese postmenopausalwomen had higher levels of soluble transferrin receptor(sTiR) than non-obese matched controls, and that bodymass index (BMIl was positively associated with sTfR.

Nurririon RevieW<;- Vol. 67(2):100-104

Recent studies have utilized sTfR as an indicator of ironstatus because this assay is not affected by the acute-phaseresponse, as are other indicators of iron status, includingserum ferritin.l \ Elevated sTiR levels arc indicative of irondeficiency because erythrocytes in the bone marrowincrease the presentation of membrane transferrin receptor in the presence of low levels of iron.ll In anotherrecent study, Menzie et al.lJ found signifICantly lowerlevels of serum iron and transferrin saturation (the ratioof serum iron to total iron binding capacity) in obese ascompared to non-obese adult volunteers, and fat masswas shown to be a Significant negative predictor of serumiron concentration. In a third study, using cut-off valuesfor serum iron and sTfR, Yanoff et al.l '! confirmed anincreased prevalence of iron deficiency in obese as compared to non-obese adults; in that study, serum iron wassignificantly lower and sTiR was significantly higher inthe obese individuals. Similar to the Lecube et aP andMenzie et al. lJ studies, this study uncovered significantcorrelations between serum iron, sTfR, fat mass, and BMIin adults. Collectively, these reports suggest that excessadiposity may negatively affect iron status.

INFLAMMATION AND IRON ABSORPTION

Zimmermann et a1. l5 recently studied unique populationsto test the hypothesis that obesity may affect iron absorption through an inflammatory mediated mechanism. Inthese studies, women and children from transition countries, including 'lbailand, Morocco, and India, were utilized to investigate the relationship bctween 8MI andiron absorption. Volunteers from transition countrieswere selected because these countries are undergoingrapid socioeconomic changes that have resulted in bothmalnutrition and ovcrweight. For example, in Bangkok,Thailand, nearly 33% of women are ovenveight, and 24%arc anemic.l5·l~ Zimmermann et al. l5 refer to this circumstance as the "double burden" of the nutrition transition.

In the first experiment, 67 apparently healthy premenopausal Thai women were recruited to consumeiron· isotope-labeled test meals and 25 women wererecruited to serve as healthy controls. In this study, 22% ofthe women were considered overweight and 20% wereiron deficient. The test meals, which consisted of foodstypical to the Thai diet, contained approximately 4 mgof isotopically labeled fortification iron as [57Fe/~'Fel_

ferrous sulfate. Prior to the meal, blood was analyzed foriron status indicators, including hemoglobin and serumferritin. Inflammation was assessed using C-reactiveprotein. Fourteen days after the test meal a second bloodsample was collected for the determination of isotopcconcentration and the calculation of iron absorptionusing mass spectrometry. The major fInding was thatafter correcting for differences in initial iron status, mulli-

101

variate regression indicated that fractional iron absorption was negatively correlated with C-n'active proteinand BM!.

In the k"Cond experiment, Zimmermann et a1.~ combined data from four controlled efficacy trials of ironfortification using children from Morocco and India. l1- lt

In these trials, responsiveness to iron fortification usingiron salts, including encapsulated ferrous sulfate andmicronized ferric pyrophosphate. was assessed in children and adolescents aged 5-16 years. The combinedstudy population totaled 1688 children. Iron status indicators, including hemoglobin, serum ferritin, sTIR, andwhole-blood zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP) .....ere measuredat baseline and following the 7-9-month fortificationprotocols. In these studies. the prevalence of overweightwas 6%; this was lower than the prevalence reported inthe adult study, although the prevalence of iron deficiency was higher, at 42%. The major findings indicatedthat in the combined baseline data. there was an inverserelationship between 8MI Z-score and body iron, calculated from the serum ferritin/sTIR ratio. Furthermore.8MI was a significant negative predictor of body iron anda positive predictor of sTIR and ZPP at baseline, indicating that greater 8MI was associated with degraded ironstatus. When considering the responsiveness to iron fortification, there was an inverse relationship between 8MIZ-score and change in body iron. Greater 8MI Z-scorewas a significant negative predictor of change in ironstatus, as assessed using the response of serum ferritin,s11R, and ZPP. It should be noted that the associationbetween greater 8M [ Z-score and change in serum ferritin was weaker than the relationship with the other ironstatus indicators, as serum ferritin may have been elevatedin response to adipose-related inflammation, whereasother indicators, including sTfR, are not affected byinflammation.J1 The possible elevation in serum ferritinin response to inflammation may have also affected therelationship between 8MI Z-score and body iron. Takentogether, these studies conflm1 the association of diminished iron status with obesity; they also indicate, for thefirst time, that iron absorption is directly affected byinflammation and BMI. As such, these studies are amongthe first to identify the inflammatory response to obesityand increased body fat as a major effector of iron homeostasis in children and adults.

WHAT IS THE MECHANISTIC LINK BETWEEN BODY FATAND POOR IRON STATUS?

If overweight and obese individuals are at greater risk forreduced iron absorption and iron deficiency, what is themechanistic link between body fat and iron homeostasis?A number of hypotheses have been proposed, includingincreased plasma volume in the obese. the consumption

102

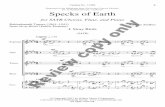

Pro-Inflammatory Diminished IronObesity _ Cytokines _ ft ~e.~,_(Il~. TN~ ,~ --.-.- Absorption

Figure 1 Proposed mec.hanistic link between obesityand poor iron status.

of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods,.lG and chronicinflammation in response to excess adiposity.14 Few ofthese hypotheses have been explored in detail. Theincreased levels of both C-reactive protein and ferritinobserved in the obese populations in the Yanoff et a1. l '

study suggest that inflammation could contribute todiminished iron status. In the obese, serum ferritin isoften elevated in response to inflammation, even in casesof iron deficiency; this highlights the utility of iron statusindicators, including sTIR, which are not affected by theacute-phase r(.'Sponse, for the identification of iron deficiency. The studies by Zimmennann et al. have providedimportant evidence that obesity influences iron absorption; however, the contribution to our understanding ofthe mechanism by which obesity affects iron status wouldhave been improved by the direct assessment of proinflammatory cytokines and hepcidin in these studies.

Is there a hepcidin-inflammation connection?

Hepcidin is an important regulator of iron homeostasis,inhibiting iron absorption at the enterocyte and sequestering iron at the macrophage;lO which could lead todecreased iron stores and hypoferremia. Obesity causeschronic inflammation,ll which is associated with theexpression and release of pro-inflammatory cylokines,including interleukin-6 01.-6) and tumor necrosisfactor-ll (TNF-a). 'Ibese prO-inflammatory cytokinesmay result in the release of hepcidin from the liver ord· . nll ·'·h fa Ipose llssue.' e potential role 0 hepcidin in the

development of iron deficiency in the obese is supportedby the discovery of elevated hepcidin levels in tissue frompatients with seVere obesity, and the positive correlationbetween adipocyte hepcidin expression and 8MI(Figure 1).J1 Even though the hcpcidin-inflammationconnection provides a succinct biological framework toexplain the association of iron defiCiency with obesity,additional research is required.

CONClUSION

The independent consequences of iron deficiency andobesity have been well characterized. The recentlydescribed connection between iron deficiency andobesity is a cause for public health concern, as the combined impact of these nutritional comorbidities isunknown.l:urthennore, the prevalence of obesity contin-

NlItrition RMews- Vol 67(1}:IOO-I04

ues to climb in both developed and developing nations.

As described in this manuscript, the inflammation asso

ciated with increased adiposity seems to be a mechanistic

link between iron status and obesity. However, conclusive

experiments establishing a dir«t connection between

measured hepcidin levels. pro-inflammatory cytokines.

and adiposity have yet to appear in the literature. The

design and execution of these experiments, coupled with

the development of appropriate ceU and animal models/'

will be critical to furthering understanding of the mecha

nistic relationship between iron status and obesity. More

over, the understanding of this mechanistic relationship

may allow for the development of nutritional and/or

pharmacologic therapies that could prevent the develop

ment of iron deficiency in the obese.

Acknowledgment

The opinions or assertions contained herein arc the

private views of the authors and arc not to be construed as

official or as reflecting the views of the Army or the

Department of Defense. Any citations of commercial

organizations and trade nanles in this report do not

constitute an official Department of the Army endorse

ment of approval of the products or services of these

organizations.

REFERENCES

1. Stoltzfus RJ. Defining iroo-defKiency anemia in publk healthterms: time for reflection. J Nutt. 2oo1;131(Suppl):S565SS67.

2. Gardner GW, Edgerton VR. Senewiratne B, B.arnard RJ.Ohira Y. Physical worle. capacity and metabolic stress in subjects with iron deficiency anemia. Am J C1in Nutr.1977;30:910-917.

3. (clSin9 F, Blomstrand E, Werner B, Pihlstedt P, Ekblom B.Effects of iron deficiency on endurance and muscle enzymeactivity in man. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1986;18:156-161.

4. Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Iron treatment normalizes cognitive functioning in young women. Am J Clin Nutr.2OO7;8S:778-787.

5. Brownlie T IV, Utermohlen V, Hinton PS, Giordano C. Haas JD.Marginal iron deficierKy without anemia impairs aerobicadaptation among previously untrained women. Am J ClinNutt.2oo2;75:734-742.

6. Brownlie TlV, Utermohlen V, Hinton PS, Hoas JD. nssue irondefidency without anemia impairs adaptation in endurancecapacity after aerobic training In previously untrainedwomen. Am JOin NlSIr. 2004;79:437-443.

7. Looker A(, Cogswell ME, Gunter MT.lron deficiency - UnitedStates, 1999-2000. Morb Mortal Wldy Rep. 2002;51:897-899.

8. Nead KG, Halterman JS, Kaczorowski JM, Auinger P,We~n M. Overweight children and adolescents: a riskgroup for iron deficiency. Pediatrics. 2004;114:104-108.

9. Lecube A, Carrera A, Losada E, Hernandez C. Simo R, Mesa J.Iron deficiency in obe~ postmenopausal women. Obesity.2006;14:1724-1730.

Nutrir/on Reviews- Vol. 67(2):100-104

10. World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing ondManagingthe Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. WHOTechnical Report series 894. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

11. Ogden a... Carroll MO, Curtin LR, McDowell MAo Tabak CJ,Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in theUnited States, 1999-2004, JAMA. 2006;295:1549-1555.

12. Ogden CL. carroll MD, McDowell MAo Regal KM. Obesityamong Adu/rs in the Unit~ Stores - No Change since 20032004. NCHS data brief no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Centerfor Health Statistics; 2007.

13. World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Factsheet No. 311. 2006; Available at: hnp:JJwww.who,intlmediacentrelfaetsheetslfs311/en/index.html. Accessed 4september 2008.

14. Wang Y, lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatric Obes. 2006;1 :11-25.

15, 5erdula MK, lV{!ry 0, Coates RJ, Freedman OS, Williamson OF,Byers T. Do obes(' chHdren become obese adults? Areview ofthe literature. Prev Med. 1993;22:167-177.

16. Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson OF, Gail MH. Causespecific excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA, 2007;298:2028-2037.

17. US. Department of Health and Human Services. Tne SurgeonGeneral's (all to Action ro Prevent ond Decrease Overweighrand Obesity, Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health andHuman Services, Public Health service, Office of the SurgeonGeneral; 2001.

18. Wel'\lel BJ, Stults H8, Mayer J. Hypoferraemia in obese adolescents.l.ancet.I962;2:327-328.

19. seltzer Cc. Mayer J. serum iron and iron-binding capacity inadolesc::ents.11. Comparison of obese and nonobese subjects.Am J C1in Nutt. 1963;13:354-361.

20. Pinhas-Hamiel 0, Newfield RS, Koren I, Agmon A, LUos P,Phillip M. Greater prevalence of iron defKiency in overwei9htand obese children and adolescents. Int J Obes Relat MetabDisord.2oo3;27:416-418.

21. O'Broin 5, Kelleher B, Balfe A, McMahon C. Evaluation ofserum transferring receptor assay in a centralized iron screening service. Clin Lab Haem. 2005;27:190-194.

22. Wish lB. Assessing iron status: beyond s('rum ferritin andtransferrin saturation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;l{Suppl):54-58.

23. M('nzie CM, Yanoff LB, Oenkinger BI, ct al. Obesity-relatedhypoferremia is not explained by differences in reportedintake of heme and nonheme iron or intake of dietary factorsthat can affect iron absorption. J Am Diet Assoc.2008;108:145-148.

24. Yanoff LB, Menzie CM, Denkinger B, et at Innammation andiron deficiency in the hypoferremia of obesity. Int J Obes(Lond). 2007;31:1412-1419.

2S. Zimmermann MB, Zeder C. MlSIhayya S, et at Adiposity inwomen and children from transition countries predictsdecreased iron absorption, iron deficiency and reducedresponse to iron fortification. Int J Obes n.ond). 2008;32:109B-ll04.

26. Kantachuvessiri A. Obesity in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai.2oo5;88;5~S62.

27. Zimmermann MB, Zeder C. Chaouki N, Saad A, Torresani T,Hurrell RF. Dual fortification of sah with iodine and microencapsulated iron: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trialin Moroccan schoolchildr('n. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:425-432.

28. Zimmermann MB, Wegmueller R, Zeder C. et al. Dualfortification of salt with iodine and micronized ferric

103

pyrophosphate: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial.Am 1 C1in NUlr.2004;80:952-959.

29. Moreni 0, Zimmermann MS, Muthayya S, et al. Extruded ricefortified with miaonized groond ferric pyrophosphatereduces iron deficiency in Indian schoolchildren: a doubleblind randomized controlled trial. Am J C1in Nutr. 2006;84:822-829.

30. Knutson Mo, Oukka M. Koss LM. Aydemir F,Wessling-Resnick M. Iron release from macrophages aftererythrophagocytosis is up-rtgulated by ferroportin 1 overell:pression and down-regulated by hepcidin. Proc Natl Acad SciUSA. 2005;102:1324-1328.

'"

31. Greenberg AS, Obin M5. Obesity and the role of adiposetissue in inflammation and metabolism Am 1 Clin Nun.2006;83(5uppl):S461-S465.

32. 8ekri 5, Gual P, Anty R,. eta!. Inaeased adipose tissueell:pression of hepcidin in severe obesity is independent fromdiabetes and NASH. Gastroenteroloqy.lOO6;131:788-796.

33. Wrighting OM, Andrews NC. Interieukin-6 induces hepcidin exPf~ion through STAn. Blood. 2006;108:3204-3209.

34. McClung JP, Andersen NE, Tarr TN, Stahl CH, Young AJ.Physical activity prevents alJgmented body fat accretionin moderately iron-deficient ralS. J Nutr. 2008;138:12931297.

Nutrition Reviews· Vol. 67(2}:100-104