Hermeneutics as Comparative-Historical Method

description

Transcript of Hermeneutics as Comparative-Historical Method

北京师范大学北京师范大学教育研究方法讲座系列教育研究方法讲座系列

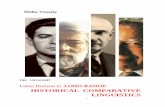

Lecture 8Approach to Comparative-Historical Method (5):

Critical Hermeneutic Perspective

2

Hermeneutics as Comparative-Historical Method

1. The meanings of hermeneutics: a. Marin Jay points out that hermeneutics “originally a

Greek term, it referred to the god Hermes. The sayer or announcer of divine messages ― often, to be sure in oracular and ambiguous form. Hermeneutics retained its early emphasis on saying as it accumulated other meanings, such as interpreting, translating, and explaining.” (Jay, 1982, P. 90)

3

Hermeneutics as Comparative-Historical Method

1. The meanings of hermeneutics: b. Paul Ricoeur’s provides a working definition of

hermeneutics as follow:

“Hermeneutics is the theory of the operations of understanding in the relation to the interpretation of texts.” (Ricoeur, 1981a, p.43)

4

Hermeneutics as Comparative-Historical Method

1. The meanings of hermeneutics: b. "What is hermeneutics? Any meaningful expression—be it an

utterance, verbal or nonverbal, or an artifact of any kind, such as tool, an institution, or a written document—can be identified from a double perspective, both as an observable event and as an understandable objectification of meaning. We can describe, explain, or predict a noise equivalent to the sounds of a spoken sentence without having the slight idea what this utterance means. To grasp (and state) its meaning, one has to participate in some (actual or imagined) communicative action in the course of which the sentence in question is used in such a way that it is intelligible to speakers, hearers, and bystanders belonging to the same speech community." (Habermas, 1996, p. 23-24)

5

Hermeneutics as Comparative-Historical Method

2. Levels of hermeneutic inquiriesa. Hermeneutics at literal level: Decoding the authentic

meanings embedded in literal texts or in utterances in dialogues

b. Hermeneutics at ontological level: ① Encoding and decoding meanings from the ontological condition of

the author

② Encoding and decoding meanings from the ontological condition of the world referred in the text

6

Hermeneutics as Comparative-Historical Method

2. Levels of hermeneutic inquiriesc. Hermeneutics at historical and cultural level: Encoding and

decoding meanings from the historical and cultural context within which the text was produced

d. Hermeneutics at the ontological/existential level: ① Hermeneutic experience as “the corrective by means of which

thinking reason escapes the prison of language." (Gadamer, 1975, Quoted in Habermas, 1988, p. 144)

② Hermeneutics as the “fusion of horizons” of that of the author and reader

7

Paul Ricoeur’s Literal Hermeneutics as Bridging of the Distanciations in the text

(See Explications in Lecture 7)

8

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

1. Existential understanding of language:a. Following the teaching of his teacher Heidegger, Gadamer

see that “all human reality is determined by its linguisticality. …Because human beings are thrown into a world already linguistically permeated, they do not invent language as a tool for their own purposes. It is not a technological instrument of manipulation. Rather, language is prior to humanity and speaks through it. Our infinite as human beings is encompassed by infinity of language.” (Jay, 1982, P. 94)

1900-2002

10

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

1. Existential understanding of language:b. Accordingly, human existence is a linguistically encoded

existence, which is made up of all the preconceptions or what Gadamer called “prejudices” accumulated and sustained in a particular cultural-linguistic “tradition”. Hence, as human agents speak and act, they are speaking and acting within a prison house of language.

11

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

2. The conception of hermeneutic experience: In order to liberate oneself from such a prison of language, Gadamer suggests that human agents have to undertake the hermeneutic experience.

12

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

"Hermeneutic experience is the corrective by means of which thinking reason escapes the prison of language, and it is itself constituted linguistically …. Certainly the variety of languages presents us with a problem. But this problem is simply how every language, despite its difference form other languages, is able to say everything it wants. …We then ask how, amid the variety of forms of utterance, there is still the same unity of thought and speech, so that everything that has been transmitted in writing can be understood." (Gadamer, 1975, Quoted in Habermas, 1988, p. 144)

13

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

3. Gadamer’s redefinition of hermeneutic inquiry: a. Within Gadamer’s framework of existential linguistics,

hermeneutics is no longer simply an act of empathetic bridging other distanciations within the text, particularly historical text, revealing what actually happened in the past, as Ranke advocated; but to “fuse” the horizons of the reader and the author. This is what Gadamer calls “fusion of horizons”.

14

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

3. Gadamer’s redefinition of hermeneutic inquiry: b. By horizon, Gadamer defines it as “the range of vision that

includes everything that can be seen from a particular vantage point.” (Gadamer, 1975, Quoted in Jay, P. 95) However, individual horizons are partial and incomplete. Furthermore, they “are open, and shift; we wander into them and they in turn move with us.” (Habermas, 1988, P. 147)

15

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

4. Varieties of hermeneutic experiences and inquiries: Accordingly, such a fusion of horizons may take varieties of formsa. Hermeneutic experiences of the translator striving to bridge

two languages

b. Hermeneutic experience of the historian attempting to bridge two epochs

c. Hermeneutic experience of the anthropologist trying to bridge two cultures

16

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

4. Varieties of hermeneutic experiences and inquiries: …d. Hermeneutic experience of the sociologist trying to bridge

two classes, status groups and political parties

e. Hermeneutic experience of the comparative-historical researcher striving of bridge big structures, large process and great communities across times and spaces

17

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

5. Gadamer’s concepts of authority and tradition: a. The notion of “legitimate prejudice”: According to

Gadamer, human agents could only approach the world with preconceptions or “prejudices” of accumulated and sustained in a particular cultural-linguistic community. However, in hermeneutic experiences and inquiries, the fusion of horizons may not be smooth and harmonious but in contradictions or even conflicts. As a result, prejudices and their constituent horizons must be justified in situations where encounters and fusions of horizons take place. That brings about Gadamer’s the concept of authority and the issue of “legitimate prejudice”.

18

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

5. Gadamer’s concepts of authority and tradition:… b. Gadamer contends that the legitimacy of individual horizons

and its prejudices are gained in daily-life practices of speech acts, discourse and understanding within a prevailing cultural-linguistic community. While the legitimate “prejudices” at social level can also establish their authority in dialogues, social interactions and institutional practices. Therefore, Gadamer contends that “authority, properly understood, has nothing to do with blind obedience to a command. Indeed, authority has nothing to do with obedience, it rests on recognition.” (Gadamer, 1975, Quoted in Ricoeur, 1991, P. 279) …

19

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

5. Gadamer’s concepts of authority and tradition:… b. … By recognition, Gadamer refers to “that the other is

superior to oneself in judgment and insight and that for this reason his judgment takes precedence, i.e. it has priority over one’s own.” (Gadamer, 1975, Quoted in Ricoeur P. 278) “This is the essence of the authority, claimed by the teachers, the superior, the expert.” (Gadamer, 1975, Quoted in Ricoeur 991, P. 279)

20

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Existential Hermeneutics as Fusion of Horizons

5. Gadamer’s concepts of authority and tradition:… c. As these “legitimate prejudices” sustained and spread their

authority within a linguistic community, they establish what Gadamer calls their “effective-historical” status and become the “tradition”. “This is precisely what we call tradition: the ground of their validity…. tradition has a justification that is outside the arguments of reason and in large measure determines our attitudes and behavior.” (Gadamer, 1975, Quoted in Ricoeur, 1991, P. 279)

21

Jurgen Habermas’ Critical Hermeneutics

1. The focus of contention between on Gadamer and Habermas is exactly on the difference in the authority of prejudice and conception of tradition. Habermas disagrees to Gadamer’s treatment of the tradition and its authority of prejudices in a given cultural-linguistic community as normative imperatives derived out of practical speech acts, discourses and fusions of horizons. Instead Habermas underlines the power and domination that are at work in all human relationships including linguistic communications. …

22

Jurgen Habermas’ Critical Hermeneutics

1. …In Habermas own words, “This metainstitution of language as tradition is evidently dependent in turn on social processes that are not in normative relationship. Language is also medium of domination and social power.” (Habermas, 1977, Quoted in Jay, 1982, P. 99)

23

Jurgen Habermas’ Critical Hermeneutics

2. From the stance of the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School as well as of Marxism, Habermas criticizes Gadamer of neglecting the frozen ideology, hypostatized power, and systemic distortion that may have been prevailed in cultural-linguistic traditions as well as in its supporting institutions.

24

Jurgen Habermas’ Critical Hermeneutics

3. Critical hermeneutics: According to Habermas’ critique on Gadamer’s existential hermeneutics, Habermas has elevates hermeneutic inquiry yet to another level, namely critical hermeneutics. a. First of all, Habermas criticizes Gadamers’ conception of

authorities of “prejudices” and tradition of neglecting the notion of power that is supposed to be at work behind all these authority. This brings out one of the basic concept in the Critical Theory, i.e. the hypostatized power, which is at work in all human relationships and discourses.

25

Jurgen Habermas’ Critical Hermeneutics

3. Critical hermeneutics: …b. Accordingly, this hypostatized will impose systemic

distortions to human relationships and discourses.

c. One of these systemic distortions, which manifests in individual horizon, fusion of horizons, prejudices, and tradition, is the ideological elements frozen in these cultural-linguistic representations.

26

Critical Hermeneutic Analysis: An Illustration Michel Foucault’s Discourse, Genealogy and Power

27

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

1. From text and narrative to discourse: Three constituents of the linguistic turna. The task of literal hermeneutics is to ‘describes the

phenomenon from the inside’ (Dreyfus & Rabinow, 1982, p.79), that is, to retrieves the meanings embedded in the text, and to bridge the distanciation between the ‘being-in- the-world’ of the author and reader

28

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

1. From text and narrative to discourse: Three constituents of the linguistic turnb. The task of narrative study is to reveal 'forms', 'plots',

'meanings', and narratives that historians have imposed upon historical data in their writings historical storylines. That is to reveal 'the content of the form' of historians' representations.

29

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

1. From text and narrative to discourse: Three constituents of the linguistic turnc. Archaeology in Foucaultian sense look into how discourses

are formed in the history of ideas and/or truth. Foucault contends that in studying the successions of schools of thought in the history of ideas, one should look beyond the internal meanings of the school of thought under study but analyze the discursive rules in operations in a given historical and socio-cultural contexts. Furthermore, Foucault’s discourse analysis reveals the underlying “technology of power” at work in the process of discourse formation….

30

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

1. From text and narrative to discourse: Three constituents of the linguistic turnc. … “Foucault, the archaeologist looks from outside, reject the

appeal to meaning. He contends that viewed with external neutrality, the discursive practices themselves provide a meaningless space of rule-governed transformations in which statements, subjects, objects, concepts and so forth are taken by those involved to be meaningful.” (Dreyfus & Rabinow, 1982, p. 79)

31

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

1. From text and narrative to discourse: Three constituents of the linguistic turnc. … “Foucault, the archaeologist looks from outside, reject the

appeal to meaning. He contends that viewed with external neutrality, the discursive practices themselves provide a meaningless space of rule-governed transformations in which statements, subjects, objects, concepts and so forth are taken by those involved to be meaningful.” (Dreyfus & Rabinow, 1982, p. 79)

32

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

2. Statements and Discourse a. Statement “The statement is not the same kind of unit as the

sentence, the proposition, or the speech act…The statements is not …a structure (i.e. a group of relations between variable elements...).; it is a function of existence that properly belong to signs and on the basis of which one may then decide, through analysis or intuition, whether or not they ‘make sense’, according to what rule they follow one another or are juxtaposed, of what they are the sign, and what sort of act is carried out by their formulation (oral or written).” (Foucault, 1972, p. 86-87)

You are insane

You are sick

You are condemned

You are sexually, inappropriate

& immoral

34

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

2. Statements and Discourse b. A discourse “is the totality of all effectiveness statements

(whether spoken or written). ... Description of discourse is in opposition to the history of thought. There…a system of thought can be reconstituted only on the basis of a definite discursive totality. …The analysis of thought is always allegorical in relation to the discourse that it employs. Its question is unfailingly: what is being said in what was said? …what is this specific existence that emerges from what is said and nowhere else?” (Foucault, 1972, p. 27-28)

35

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

3) The Formation of Objecta. Mapping the surface of the emergence of the object

b. Describing the authorities of delimitation

c. Analyzing the grids of specification

36

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

4. The Formation of Enunciative Modalitya. Identifying who is speaking, who is accorded the right to use

this sort of language, who is qualified to do so.

b. Describing the institutional sites from which the discourse is made and form which the discourse derives its legitimate source and point of application

c. Analyzing the position of the subject, in which s/he occupies in relation to the various domains and groups of objects

37

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

5. The Formation of Concepts: the formation of the organization of the field of statements where they appeared and circulated a. Identifying the forms of succession, e.g.

Orderings of enunicative seriesTypes of dependence of the statementRhetorical schemata according to which groups of statements may be

combined

b. Identifying the forms of coexistenceField of presenceField of concomitanceField of memory

38

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

5. The Formation of Concepts: …c. Identifying the procedures of intervention that may be

legitimately applied to statements, e.g. technique of rewriting , method of transcribing, mode of translating, means of transferring, method of systematizing

39

Michel Foucault’s Conceptions of Discourse

6. The Formation of Strategies or theoretical and thematic choicea. Determining the points of diffraction of discourse

① Point of incompatibility

② Point of equivalence

③ Point of systematization

b. Analyzing the economy of the discursive constellation

c. Analyzing the other authority, e.g. functional to fields of non-discursive practice, observing the rules and processes of appropriation of discourse

40

Michel Foucault’s Conception of Power

1. Power as subjection and subjugationa. “I would like to say, first of all, what has been the goal of my

work during the last twenty years. It has not been to analyze the phenomena of power, nor to elaborate the foundations of such an analysis. My objective, instead, has been to create a history of the different mode by which, in our culture, human beings are made subjects... Thus it is not power, but the subject, which is the general them of my research.” (1982, 208-209)

41

Michel Foucault’s Conception of Power

1. Power as subjection and subjugationb. Power as objectification of subjection: The technology of

power① Objectification in transformation of human beings into subjects of

human sciences, e.g. philology, linguistics, biology, economics, …

② Objectification in turning identified human beings into subjects of “dividing practices”, e.g. the insane, the sick, the convicted, the uneducated, …

③ Objectification in turning human themselves into subjects…..

42

Michel Foucault’s Conception of Power

1. Power as subjection and subjugationb. Typology of power: Emerged from Foucault’s studies of

power, there are at least four conceptions of power ① Disciplinary power

② Biopower

③ Pastoral power

④ Sovereign power

43

Discourse, Genealogy and Power

1. From Discourse to genealogy: The methodological linka. Archaeology and genealogy as different levels interpretation:

① Archaeological level of interpretation: “Whether we are analyzing propositions physics or phrenology, we substitute for their internal intelligibility a different intelligibility, namely their place within the discursive formation. This is the task of archaeology …Archaeology is always a technique that can free us from a residual belief in our direct access to objects; in each case the ‘tyranny of the referent’ has to be overcome.” (Dreyfus & Rabinow, 1982, p. 117)

② Genealogical level of interpretation: "When we add genealogy, however, a third level of intelligibility and differentiation is introduced. After archaeology does its job, the genealogist can ask about the historical and political roles that these science play.” (Dreyfus & Rabinow, 1982, p. 117, my italic)

44

Discourse, Genealogy and Power

1. From Discourse to genealogy: The methodological linkb. Genealogy as study of Episteme and Entstehung:

① Episteme as descents of discourses

② Entstehung• ‘Entstehung designates emergence, the moment of arising.”

(Foucault, 1984, p.83)

• Emergence is always produced through a particular stage of forces. The analysis of the Entstehung must delineate this interaction, the struggle these forces wage against each other or against adverse circumstances, and the attempt to avoid degeneration and regain strength by dividing these forces against themselves.” (p.83-84)

45

Discourse, Genealogy and Power

2. The Concept of Power/Knowledge:a. ‘It is in discourse that power and knowledge are joined

together’ (Foucault, 1978, p. 100) and therefore "discourse is both instrument and effect of power." (1978, p. 101), Accordingly it is through discourse that constitutes what Foucault conceptualized the power/knowledge.

46

Discourse, Genealogy and Power

2. The Concept of Power/Knowledge:b. ‘We should admit … that power and knowledge directly imply

one another; that there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations. These power/knowledge relations are to be analyzed, therefore, not on the basis of a subject of knowledge who is or is not free in relation to the power system, but, on the contrary, the subject who knows, the objects to be known and the modalities of knowledge must be regarded as so many effects of these fundamental implications of power/knowledge and their historical transformations. …

47

Discourse, Genealogy and Power

2. The Concept of Power/Knowledge:b. … In short, it is not the activities of the subject of knowledge

that produces a corpus of knowledge, useful or resistant to power, but power/knowledge, the processes and struggles that traverse it and of which it is made up, that determines the forms and possible domains of knowledge.’ (Foucault, 1977, p. 28)

Theory

Evidence

Comparative Studies of Multiple Cases

Historical Studies of Particular Case

FunctionalEquivalence

Structural Configuration

END

Lecture 8Approach to Comparative-Historical Method (5):

Critical Hermeneutic Perspective