Hepatic Pathology

-

Upload

api-3700579 -

Category

Documents

-

view

140 -

download

6

Transcript of Hepatic Pathology

HEPATIC PATHOLOGY

Normal

Normal liver in situ

This is an in-situ photograph of the chest and abdominal contents. As can be seen, the liver is the largest

parenchymal organ, lying just below the diaphragm. The right lobe (at the left in the photograph) is larger than the left lobe. The falciform ligament is the rough dividing line

between the two lobes.

Normal liver – find hepatic artery

The color is brown and the surface is smooth. A normal liver is about 1200 to 1600 grams. The cut surface of a normal liver has a brown color. Near the

hilum here, note the portal vein (PV) carrying blood to the liver, which branches at center left, with accompanying hepatic artery and bile ducts

(BD). At the lower right is a branch of hepatic vein (HV) draining blood from the liver to the inferior vena cava.

PVBD

HV

Normal liver zones

Liver is divided histologically into lobules. The center of the lobule is the central vein (black arrow). At the periphery of the lobule are portal triads

(red arrow). Functionally, the liver can be divided into three zones, based upon oxygen supply. Zone 1 encircles the portal tracts where the oxygenated blood from hepatic arteries enters. Zone 3 is located around central veins, where oxygenation is poor. Zone 2 is located in between.

Steatosis

Fatty metamorphosis of liver (a) This liver is slightly enlarged and has a pale

yellow appearance, seen both on the capsule and cut surface. This uniform change is consistent with fatty metamorphosis (fatty change).

(b) The lipid accumulates in the hepatocytes as vacuoles. These vacuoles have a clear appearance with H&E staining. The most common cause of fatty change in developed nations is alcoholism. In developing nations, kwashiorkor in children is another cause. Diabetes mellitus, obesity, and severe gastrointestinal malabsorption are additional causes.

(c) Here are seen the lipid vacuoles within hepatocytes. The lipid accumulates when lipoprotein transport is disrupted and/or when fatty acids accumulate. Alcohol, the most common cause, is a hepatotoxin that interferes with mitochondrial and microsomal function in hepatocytes, leading to an accumulation of lipid.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis of liver

Microscopically with cirrhosis, the regenerative nodules of hepatocytes are surrounded by fibrous connective tissue that bridges between portal tracts. Within this collagenous tissue are scattered lymphocytes as well as a proliferation of bile

ducts.

Macronodular cirrhosis of liver

• LEFT: Ongoing liver damage with liver cell necrosis followed by fibrosis and hepatocyte regeneration results in cirrhosis. This produces a nodular,

firm liver. The nodules seen here are larger than 3 mm and, hence, this is an example of "macronodular" cirrhosis.

• RIGHT: Here is another example of macronodular cirrhosis. Viral hepatitis (B or C) is the most common cause for macronodular cirrhosis. Wilson's disease and alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency also can produce a macronodular cirrhosis.

Micronodular cirrhosis of liver

• LEFT: The regenerative nodules are quite small, averaging less than 3 mm in size. The most common cause for this is chronic alcoholism. The process of cirrhosis develops over many years.

• RIGHT: This magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen in transverse view demonstrates a small, nodular liver with cirrhosis (L). The spleen (S) is enlarged from portal hypertension.

L

S

Micronodular cirrhosis and fatty change of liver

(a) The regenerative nodules are quite small, averaging less than 3 mm in size. The most common cause for this is chronic alcoholism. The process of cirrhosis develops over many years.

(b) Here is another example of micronodular cirrhosis. Note that the liver also has a yellowish hue, indicating that fatty change (also caused by alcoholism) is present.

(c) This magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen in transverse view demonstrates a small, nodular liver (L) with cirrhosis. The spleen (S) is enlarged from portal hypertension.

(a) (b)

(c)

L

S

Micronodular cirrhosis and fatty change of liver

Micronodular cirrhosis is seen along with moderate fatty change. Note the regenerative nodule surrounded by

fibrous connective tissue extending between portal regions.

Mallory's hyaline, liver

At high magnification can be seen globular red hyaline (arrow) material within hepatocytes. This is Mallory's hyaline, also known as "alcoholic"

hyaline because it is most often seen in conjunction with chronic alcoholism. The globules are aggregates of intermediate filaments in the cytoplasm

resulting from hepatocyte injury.

Alcoholic hepatitis

Mallory's hyaline is seen here, but there are also neutrophils, necrosis of hepatocytes, collagen deposition, and fatty change. These findings are typical for acute alcoholic hepatitis. Such inflammation can occur in a

person with a history of alcoholism who goes on a drinking "binge" and consumes large quantities of alcohol over a short time.

Caput medusae of skin with portal hypertension

Portal hypertension results from the abnormal blood flow pattern in liver created by cirrhosis. The increased pressure is transmitted to collateral venous channels. Sometimes these venous collaterals are dilated. Seen

here is "caput medusae" which consists of dilated veins seen on the abdomen of a patient with cirrhosis of the liver.

Esophageal varices with portal hypertension

A much more serious problem produced by portal hypertension results when submucosal veins in the esophagus become dilated. These are

known as esophageal varices. Varices are seen here in the lower esophagus as linear blue dilated veins. There is hemorrhage around one

of them. Such varices are easily eroded, leading to massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Splenomegaly with portal hypertension

One of the most common findings with portal hypertension is splenomegaly, as seen here. The spleen is enlarged from the normal 300 grams or less to between 500 and 1000 gm. Another finding here is the irregular pale tan plaques of collagen over the purple capsule known as "sugar icing" or "hyaline perisplenitis" which follows the

splenomegaly and/or multiple episodes of peritonitis that are a common accompaniment to cirrhosis of the liver.

Pigmentary Disorders

Hemosiderosis of liver

The hepatocytes and Kupffer cells here are full of granular

brown deposits of hemosiderin from accumulation of excess

iron in the liver. The term "hemosiderosis" is used to denote a relatively benign

accumulation of iron. The term "hemochromatosis" is used

when organ dysfunction occurs. The iron accumulation may lead to a micronodular cirrhosis (so

called "pigment" cirrhosis).

A Prussian blue iron stain demonstrates the blue granules of hemosiderin in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells.

Hemochromatosis can be primary (the cause is probably an autosomal

recessive genetic disease) or secondary (excess iron intake or absorption, liver disease, or numerous transfusions). Hemochromatosis leads to bronze

pigmentation of skin, diabetes mellitus (from pancreatic involvement), and

cardiac arrhythmias (from myocardial involvement).

Hemochromatosis of liver

The dark brown color of the liver, as well as the pancreas (bottom center) and lymph nodes (bottom right) on sectioning is due to extensive iron deposition in a middle-aged man with hereditary hemochromatosis

(HHC). HHC results from a mutation involving the hemochromatosis gene

(HFE) that leads to increased iron absorption from the gut.

LPO

The Prussian blue iron stain reveals extensive hepatic hemosiderin

deposition microscopically in this case of hereditary hemochromatosis (HH). Note that there is also cirrhosis. Excessive iron deposition in persons with HH can affect many organs, but heart (congestive failure), pancreas (diabetes mellitus), liver (cirrhosis

and hepatic failure), and joints (arthritis) are the most severely

affected.

Lipochrome (lipofuscin) pigment in liver

The pale golden brown finely granular pigment seen here in nearly all hepatocytes is lipchrome (lipofuscin). One such deposit within a

hepatocyte is marked by the arrow. This is a "wear and tear" pigment from the accumulation of autophagolysosomes over time. This pigment

is of no real pathologic importance.

Cholestasis of liver

The yellowish-green accumulations of pigment seen here are bile. Most often this is due to extrahepatic biliary tract obstruction. However, bile may also accumulate in liver

(called cholestasis) when there is hepatocyte injury.

Intrahepatic lithiasis, liver

Here is an example of intrahepatic obstruction with a small stone in an intrahepatic bile duct. This could produce a localized cholestasis, but the serum bilirubin would not be increased, because there is plenty of non-

obstructed liver to clear the bilirubin from the blood. However, the serum alkaline phosphatase is increased with biliary tract obstruction at any level.

Neoplasms

Hepatic adenoma

(a) At the upper right is a well-circumscribed neoplasm that is arising in liver.

(b) The cut surface of the liver reveals the hepatic adenoma. Note how well circumscribed it is. The remaining liver is a pale yellow brown because of fatty change from chronic alcoholism.

(c) Normal liver tissue with a portal tract is seen on the left. The hepatic adenoma is on the right and is composed of cells that closely resemble normal hepatocytes, but the neoplastic liver tissue is disorganized hepatocyte cords and does not contain a normal lobular architecture.

Hepatocellular carcinoma The neoplasm is large and bulky and has a greenish cast because it contains bile. To the right of the main mass are smaller satellite nodules.

Here is another hepatocellular carcinoma with a greenish yellow hue. One clue to the presence of such a neoplasm is an elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein. Such masses may also focally obstruct the biliary tract and lead to an elevated alkaline phosphatase.

The malignant cells of this hepatocellular carcinoma (seen mostly on the right) are well differentiated and interdigitate with normal, larger hepatocytes (seen mostly at the left).

Note that this hepatocellular carcinoma is composed of liver cords that are much wider than the normal liver plate that is two cells thick. There is no discernable normal lobular architecture, though vascular structures are present.

Hepatocellular carcinoma with satellite nodules

The satellite nodules of this hepatocellular carcinoma represent either intrahepatic spread of

the tumor or multicentric origin of the tumor.

Cholangiocarcinoma, liver

The carcinoma at the left has a glandular appearance that is most consistent with a cholangiocarcinoma. A liver cancer may have both

hepatocellular as well as cholangiolar differentiation. Cholangiocarcinomas do not make bile, but the cells do make mucin,

and they can be almost impossible to distinguish from metastatic adenocarcinoma on biopsy or fine needle aspirate.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma, liver

• LEFT: Note the numerous mass lesions that are of variable size. Some of the larger ones demonstrate central necrosis. The masses are metastases to the liver. The obstruction from such masses generally elevates alkaline phosphatase, but not all bile ducts are obstructed, so hyperbilirubinemia is typically not present. Also, the transaminases are usually not greatly elevated.

• RIGHT: This computed tomographic (CT) scan without contrast of the abdomen in transverse view demonstrates multiple mass lesions resulting in a markedly enlarged liver extending from right to nearly the left side of the upper abdomen. These are metastases from a colonic adenocarcinoma. A normal sized spleen is seen at the lower left.

L

S

Metastatic adenocarcinoma, liver

• LEFT: Here are liver metastases from an adenocarcinoma primary in the colon, one of the most common primary sites for metastatic adenocarcinoma to the liver.

• RIGHT: This computed tomographic (CT) scan with contrast of the abdomen in transverse view demonstrates multiple mass lesions representing metastases from a colonic adenocarcinoma. A normal spleen appears at the lower right in the image (on the patient's left).

Metastatic adenocarcinoma, liver

Microscopically, metastatic infiltrating ductal carcinoma from breast is seen on the right, with normal liver

parenchyma on the left.

Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis, liver

• LEFT: Grossly, there are areas of necrosis and collapse of liver lobules seen here as ill-defined areas that are pale yellow. Such necrosis occurs with hepatitis.

• RIGHT: The necrosis and lobular collapse is seen here as areas of hemorrhage and irregular furrows and granularity on the cut surface of the liver.

Viral hepatitis B

• LPO: Viral hepatitis leads to liver cell destruction. A mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate extends from portal areas and disrupts the limiting plate of hepatocytes which are undergoing necrosis, the so-called "piecemeal" necrosis of chronic active hepatitis.

In this case, the hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg) and hepatitis B core antibody (HbcAb) were positive.

• HPO: Individual hepatocytes are affected by viral hepatitis. Viral hepatitis A rarely leads to signficant necrosis, but hepatitis B can result in a fulminant hepatitis with extensive necrosis. A large pink cell undergoing "ballooning degeneration" is seen below the

right arrow. At a later stage, a dying hepatocyte is seen shrinking down to form an eosinophilic "councilman body" below the arrow on the left.

LPO HPO

Viral hepatitis C

• LPO: This is a case of viral hepatitis C which is at a high stage with extensive fibrosis and progression to macronodular cirrhosis, as evidenced by the large regenerative

nodule at the center right. At present, the sole laboratory test for identification of this form of viral hepatitis is the hepatitis C antibody test. Hepatitis C accounts for most (but not all) cases formerly called "non-A, non-B hepatitis".

• HPO: This is a case of viral hepatitis C, which in half of cases leads to chronic liver disease. The extent of chronic hepatitis can be graded by the degree of activity (necrosis and inflammation) and staged by the degree of fibrosis. In this case, necrosis and inflammation are prominent, and there is some steatosis as well. Regardless of the grade or stage, the etiology of the hepatitis must be sought, for the treatment may depend upon knowing the cause, and chronic liver diseases of different etiologies may appear microscopically and grossly similar.

LPOHPO

Viral hepatitis with collapse, liver

This trichrome stain demonstrates the collapse of the liver parenchyma with viral hepatitis. The blue-staining areas are the connective tissue of many portal tracts that have collapsed together.

Miscellaneous Parenchymal Diseases

Chronic passive congestion (nutmeg liver)

Note the dark red congested regions that represent

accumulation of RBC's in centrilobular regions.

Microscopically, the nutmeg pattern results from congestion around

the central veins, as seen here. This is usually due to

a "right sided" heart failure.

Centrilobular necrosis, liver

If the passive congestion is pronounced, then there can be centrilobular necrosis, because the oxygenation in zone 3 of the hepatic lobule is not great. The light brown pigment seen here in the necrotic hepatocytes around the central vein is lipochrome.

Chronic passive congestion with "cardiac cirrhosis", liver

If chronic hepatic passive congestion continues for a long time, a condition called "cardiac cirrhosis" may develop in which there is fibrosis bridging between central zonal regions, as shown below, so that the portal tracts appear to be in the center

of the reorganized lobule. This process is best termed "cardiac sclerosis" because, unlike a true cirrhosis, there is minimal nodular regeneration.

Infarction, liver

At the right are seen several infarcts of the liver. Infarcts are uncommon because the liver has two blood supplies-portal venous system and hepatic arterial system. The infarcts seen here are yellow, with geographic borders and surrounding hyperemia. About half of liver infarcts occur with arteritis,

and the remaining half are due to a variety of causes.

Necrosis with acetaminophen overdose, liver

There is extensive hepatocyte necrosis seen here in a case of acetaminophen overdose. The hepatocytes at the right are dead, and those at the left are dying. This pattern can be seen with a variety of hepatotoxins. Acute liver

failure leads to hepatic encephalopathy.

Dominant polycystic kidney disease with polycystic liver

• LEFT: Numerous cysts appear in this liver from a patient with dominant polycystic kidney disease (DPKD). Such cases occur in adults and manifest with renal failure beginning in middle age. Sometimes the liver (as seen here) can be affected as well by polycystic change. Less commonly the pancreas is involved. These patients with DPKD can also have berry aneurysms in the cerebral arteries.

• RIGHT: This transverse CT scan of the liver demonstrates multiple large cysts in the parenchyma, consistent with polycystic change in the liver of a patient with dominant polycystic kidney disease.

L

Primary biliary cirrhosis

This is a case of primary biliary cirrhosis, a rare autoimmune disease (mostly of middle-aged women) that is characterized by destruction of bile ductules within the triads of the liver. Antimitochondrial antibody can be detected in

serum. Seen here in a portal tract is an intense chronic inflammatory infiltrate with loss of bile ductules. Micronodular cirrhosis ensues.

Anti-mitochondrial antibody, immunofluorescence microscopy

This immunofluorescence pattern is positive for anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) which has an association with primary biliary cirrhosis. The tissue

substrate for this test is renal parenchyma, and the tubule cells have lots of mitochondria, which stain bright green.

Extrahepatic biliary atresia, liver

This 3 month old child died with extrahepatic biliary atresia, a disease in which there is

inflammation with stricture of hepatic or common bile ducts. This leads to marked cholestasis with intrahepatic bile duct proliferation, fibrosis, and

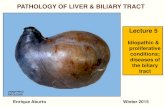

cirrhosis. This liver was rock hard. The dark green color comes from formalin acting on bile pigments in the liver from marked cholestasis,

turning bilrubin to biliverdin.

Microscopically, extrahepatic biliary atresia leads to this appearance in the liver, with

numerous brown-green bile plugs, bile duct proliferation (seen at lower center), and extensive fibrosis. If a large enough bile duct can be found to anastomose

and provide bile drainage, then surgery can be curative.

Neonatal giant cell hepatitis

Seen here is the major differential diagnosis of biliary atresia: this is neonatal giant cell hepatitis. There is lobular disarray with focal hepatocyte necrosis,

giant cell transformation, lymphocytic infiltration, Kupffer cell hyperplasia, and cholestasis (not seen here). Neonatal hepatitis may be idiopathic or of viral

origin. Many neonates recover in a couple of months.

Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, liver, PAS stain

The periportal red hyaline globules seen here with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain are characteristic for alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (a person with

homozygous pi-ZZ genotype) The globules are intrahepatic collections of alpha-1-antitrypsin that is not being excreted from the hepatocytes. This may eventually

lead to a macronodular cirrhosis. These patients are also prone to develop panlobular emphysema of lungs.

Sclerosing cholangitis, liver

• LEFT: This trichrome stain of the liver demonstrates extensive portal tract fibrosis with sclerosing cholangitis. The hepatocytes are normal.

• RIGHT: Microscopically, this bile duct in a case of sclerosing cholangitis is surrounded by marked collagenous connective tissue deposition.

Gigi - sec D – ustmed2007