Helvetica Typography Booklet

-

Upload

rachel-herring -

Category

Documents

-

view

230 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Helvetica Typography Booklet

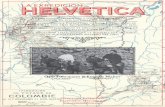

Helvetica

Assignment: This project is the final in Typographics GDES 2220 spring 2014, at Auburn University. Design and produce in InDesign CS5 a 12-page booklet that introduces basic typographic information to a general audience. Choose one serif or sans-serif family (to be approved by the instructor). The design emphasis should be on concept development and the structural organization of content.The conceptual approach to each booklet will be to develope an aesthetic that expresses the attitude, feel, and personality of the type designer, the typeface itself, or the historical context of the typeface. The aesthetic should emerge from a defined visual vocabulary and should appeal to a contemporary audience.Paper: 80 pound cover stock.Production: Printed at Kemp and Son’s Printing.

Typeface: Helvetica Neue LT Std-Thin Italic, Ultra Light, Light Condensed, Light Italic, Ultra Light Italic, Light, Roman, Italic, Medium, Bold, Black.Word count: 1,803.Sources: Helvetica, http://gds.parkland.edu/gds/!lectures/history/1950/swiss.html, http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/mar/04/helvetica-one-font-to-rule-them-all, http://www.stthomas.edu/facethenation/transced_neutralityswiss.html.Created By: Rachel Herring

T he “InternatIonal typographIc Style” (1945-1985) IS a label preferred by hIStorI-anS. Designers refer to this style as “Swiss Typography” because of its origins. The Swiss typographic style was a major force in graphic design, and it still holds much

power today, especially in the area of corporate identity.The modernist push for universal letters that characterized German type design after World War I had a reprise in Swiss type design after World War II. Switzerland became a center for cutting-edge graphic design in the 1950s, and by the end of the decade, two new sans-serif types had become associated with that milieu: Helvetica, designed by Max Miedinger, and Univers, by Adrian Frutiger.These represented the latest attempt to make letters with no sense of place—indeed, that anonymity helps to account for their remarkably widespread use—and yet they were seen paradoxically as distinctly Swiss. The “neutrality” of these types seemed to belong to Swit-zerland with its traditions of political neutrality.The very names of the most successful of the Swiss sans-serifs demonstrate this paradox: “Univers” emphasizes the design’s universality (and hence internationality), while Helvetica plays off the Latin name for Switzerland, “Confoederatio Helvetica.”

In their different ways, Helvetica and Univ-ers both responded to the call for new, universal, and international sans-serif types in the mid twentieth century. Despite their international success, the prevalent use of these types in the influential Swiss graphic design movement inextricably linked them with Switzerland. In this way, the two types simultaneously express a graphic meaning of internationalism and universality while being intimately connected to the history of Swiss Typographical Design.

The SwISS’S attItude toward deSIgn is to make socially useful, universal, and sci-

entific design. Communication is improved by reducing the elements of the communi-cation to a necessary minimum. Achieving objective clarity and order is the ideal. The visual result is extreme abstraction, often based on pure geometry. Hallmarks of the style are asymmetric layouts, use of a grid, sans-serif typefaces like Helvetica, and flush left, ragged right text. The style is also associated with a preference for photog-raphy in place of illustrations or drawings. Many of the early International Typographic Style works featured typography as a primary design element in addition to its use in text.

“There are people that think type should be expressive. They have a different point of view from mine.” —Massimo Vignelli

Helvetica

Helvetica was developed in 1957 at the Haas Type Foundry of Münchenstein, Switzerland. Haas Type Foundry set

out to design a new sans-serif typeface that could compete with the successful Akzidenz-Grotesk in the Swiss market. Originally Helvetica was called Neue Haas Grotesk. Its design was based on Schelter-Grotesk and Haas’ Normal Grotesk. The aim of the new design was to create a neutral typeface that had great clarity, no intrinsic meaning in its form, and could be used on a wide variety of signage.

In 1960, the typeface’s name was changed by Haas Type Foundry’s German parent-company from Stempel to Helvetica in order to make it more marketable interna-tionally. ‘Helvetica’ is derived from the term Confoederatio Helvetica, the Latin name for Switzerland.

Characteristics• tall x-height• narrow t and f• square-looking s• bracketed top serif of 1• rounded off square tail of R

• two-storied ‘a’ with curved stem

In 1960s America, the new discipline of cor-porate identity used Helvetica like a high-pressure hose, blasting away the preceding decades of cursive scripts, pictorial logos, excitable exclamation marks and general typographical chaos. Leaving in its place a

world of cool, factual understatement. The typeface itself said as much as what was written in it—which, pretty soon, became everything.

Why do governments and corporations love Helvetica? On one hand, it makes them seem neutral and efficient, but on the other hand the smoothness of the letters makes them seem almost human. They’re always fighting the image that they’re authoritarian, bureaucratic, they’re oppressive. By using Helvetica, they can come off seeming more accessible, transparent, and accountable, which are all the buzzwords for what gov-ernments and corporations are supposed to be today. They don’t have to be acces-sible, transparent, and accountable, if they look that way.

All of us are prompted in subliminal ways. Helvetica has almost the perfect bal-

ance of push and pull in its letters and that perfect balance is saying to us, “Don’t worry, any of the problems you’re having, problems of the world, problems getting through the subway, or finding a bath-room—all those problems aren’t gonna spill over. They’ll be contained. And in fact, maybe they don’t even exist.”

In a way, Helvetica is a kind of club. It’s a mark of membership. It’s a badge that says we’re part of modern society. We share the same ideals. We want the information in the quickest most unbiased fashion which is Helvetica.

“There are people that think type should be expressive. They have a different point of view from mine.”

The aim of the new design was to create a neutral typeface that had great clarity.

“If you used Helvetica, it meant that you were in favor of the VIETNAM WAR. So how could you use it?”

helvetIca came out of IdealISm, but by the 1970s there was a need for

change. No grid, no left aligned, ragged right text, or unexpressive type. It seemed

as if there was only one trick in town though, which was, “What can designers use in-

stead of Helvetica.” Helvetica was used and overused so much and associated with so

many kind of big, faceless things that it had lost all its capacity to even look nice. There

was a need for change. People shouldn’t confuse legibility with

communication. Just because something is legible (like Helvetica) doesn’t mean it

communicates. More importantly, it doesn’t mean it communicates the right thing and vice versa. Type being difficult to initially

read may be sending a completely different message that is valid for its usage. It may

require a little more time or involvement of the reader, but it almost seems stronger that

way—if there is a very important message, that is said in a very boring nondescript way,

the message can be lost. In the 1970s, the young generation was

doing psychedelic type and all the exciting, illegible type they could find. In the 1980s,

with their minds completely confused by the disease called “post-modernism,” people

were just going around like chickens without their heads using all kinds of typefaces that

had come around, that said “not modern” in a sense.

“If you used Helvetica, it meant that you were in favor of the VIETNAM WAR. So how could you use it?” —Paula Scher

Helvetica

CAFFEINATED? This does NOT say, “caffeinated!”

“The human heart is a strange vessel. Love and hatred can exist side by side.”

The rISe of grunge typography be-came an all-consuming aesthetic for three to five years. The trend worked

its way down from the masters who origi-nally created it to anyone who already had a tendency to make mistakes and found that they looked good now instead of incompe-tent. It seemed like the barbarians were not only at the gate, but they’d stormed through and taken over.Typography was so broken by the end of the grunge period, just lying there in a twisted heap, all rules and grids cast aside. It seemed there was no way forward, that all designers could do by the end of the late 1990s was to go back, to return to an earlier way of designing—but with a new set of theories to support it.Modernism does have a more subversive side. The whole image of modernism as something that is primarily concerned with commercialism and utilitarianism is some-thing that emerged much later. The early modernism movements all had a subversive side, they were against something. It’s not that experimentation is a bad thing, but everybody was always just hunting for the next typeface all the time trying to be original. It took a lot of energy. “I can still remember a lot of students who were really disappointed because they wanted to use a certain typeface and then saw that someone else had used it and then they couldn’t use

it because they wanted to be original,” said Erwin Brinkers. That is not designing. That is creating for the sake of novelty not com-munication. Design is not the art of original-ity. It is the art of thought and process. With Helvetica this whole problem is nonexistent because everybody is using Helvetica.

But IS ItS reIgn drawIng to a cloSe? Hel-vetica is now so ubiquitous, it barely

says anything any more. Besides, many of the qualities Helvetica was once associated with aren’t quite as enthralling as they were: corporate dominance, machine-like indiffer-ence, bland conformity, American Apparel ads. It has all been seen. Talk to a graphic designer today and they will often admit an intense dislike of Helvetica. Purists have sought to reinstate the original Neue Haas Grotesk, restoring almost imperceptible details lost in Helvetica’s digital format. Oth-ers seeking an anti-Helvetica have settled on the childish Comic Sans. Profession-als love Comic Sans like a vampire loves garlic, which could explain why it’s become the default type for goofy internet memes. There’s been a noticeable growth in Avenir-typefaces in new London stores—possibly influenced by the Keep Calm And Carry On poster. Even Wes Anderson has ditched his beloved Futura in favour of busier, pre-mod-ernist typefaces like Archer Bold.To veterans like Mike Parker, though, who appreciated the nuances of type in ways

“The human heart is a strange vessel. Love and hatred can exist side by side.”

—Scott Westerfeld

HELNOVETICA

HELYEAVETICA

few people can fathom, Helvetica was an all-time classic. “What it’s all about is the interrelationship of the negative shape—the figure-ground relationship, the shapes between characters and within characters,” Parker explained in Helvetica. Its letters live “in a powerful matrix of surrounding space,” Parker continued, almost at a loss for words. “It’s…Oh, it’s brilliant when it’s done well.” But the historical relevance and contentiousness of its design is what makes Helvetica the classic it is.