HAZEL F. GABBARD - ASCD · 2005-11-29 · HAZEL F. GABBARD In this article Hazel F. Gabbard,...

Transcript of HAZEL F. GABBARD - ASCD · 2005-11-29 · HAZEL F. GABBARD In this article Hazel F. Gabbard,...

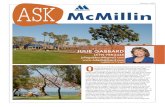

HAZEL F. GABBARD

In this article Hazel F. Gabbard, specialist for Extended School Serv-ices in the U. S. Office of Education, deals with two aspects of what isconceived to be a program of desirable living and learning for children-provision of time for play and planning for (what we so glibly term)"out-of-school" hours. In her account of what two communities are do-ing, Miss Gabbard indicates how all communities may move forwardin providing for more adequate learning experiences for children andyouth.

WHAT DO TWENTY MILLION chil-dren between six and fourteen years ofage do in their out-of-school hours-inthe afternoons, on Saturdays, and allday in summer? How many of thesechildren live in crowded homes orneighborhoods where little or no spaceis provided? What constructive playexperiences are they having in learningto get along with other children? Areschools--and communities-aware ofthe needs of these children who, be-cause of circumstances over which theyhave no control, are often deprived ofa normal childhood? These are ques-tions which concern every school andcommunity of the nation.

Leisure Time Bears Varied FruitGuidance in the use of leisure time

has long been recognized as one of themajor purposes of education. The boysand girls in our elementary schoolscomprise one-third of the population.Their leisure time occupies forty tofifty percent of their waking hours.This large block of time may bringeither tragedy or blessings to the na-tion depending on how it is spent.

Leisure spent wholly in idle amuse-ment may deteriorate mental efficiency

March 1948

and impair health. Leisure spent in self-improvement, in developing specialtalents, and in satisfying worthwhileinterests will enrich life and bring newpowers of enjoyment. Promotion ofrecreation and leisure-time activitiesfor children and youth is, for these rea-sons, assuming new importance as theresponsibility of the schools and of thecommunity.

Play for All YoungstersPlay, as the child's normal avenue for

learning, is receiving wider acceptanceas a method in modern educationalpractice. Under the stern Puritan doc-trines, which have so markedly in-fluenced American education, play wasfrowned upon and formal techniquessupplanted the play method of learningabout the world.

For very young children, play, as away of life, has been supported by re-search. Findings have been applied inthe educational methods used by nurs-ery schools and kindergartens. Beyondthese years children have usually nothad opportunities for self-expression,and formal education has taken its placein the long hours of the older elemen-tary school child.

379

Fortunately there are more schoolswhich are asking: "What is a good en-vironment for children's learning?"More educators concede that olderchildren need similar materials and spaceas planned for kindergarten children.More children are allowed the motiontheir bodies require, the outlets formuscles in running, jumping, building;and the natural play activities to openup the many avenues of information.

Play, an Avenue for LearningThrough play experiences the child's

education goes forward. For example,the intense interest today's childrenhave in airplanes helps them to accu-mulate data which is often beyond theiryears. They study minutely a toy planewith which they play. They discoverinaccuracies in pictures. They analyzephotographs of real planes. They imi-tate the sound of motors, learn to iden-tify planes by silhouettes. Gatheringand using information is a part of playand is needed to round out the experi-ence satisfactorily.

Play activities are widely used inthe modern school because they moti-vate the learning process. They arouseand sustain the child's interest, stimu-late his imagination, induce whole-hearted concentration, and yield directsatisfactions to the child. The modernschool program is built on the basicneeds of children and the understand-ing that he acquires knowledge abouthimself and others, as well as his en-vironment, through play experiences.

Not only is the point of view chang-ing as to how children learn, but alsobarriers are being lifted so educationcan go on within and without theschool's walls. Many forward-looking

380

school systems are now providing pro-grams for both children and youthafter school, on Saturdays, and duringthe summer months. The magnet whichdraws children to these extended schoolservices is a broad educational and rec-reational program consisting of a widerange of program offerings.

Recreation's Place in a Six-Day Program

In the public schools of a mid-west-ern community where nearly one-thirdof the school population attends schoolvoluntarily six days a week, a recrea-tion program is conducted and fi-nanced as an integral part of the schoolprogram. There are quite definite andspecific purposes around which theservice is organized:

- Development of physical fitnessthrough expanded opportunities forparticipation in vigorous sports andgames

N Supervised recreational care for chil-dren of working mothers

0 Enrichment of life through the pro-vision of opportunities for every childto make the most satisfying use pos-sible of his leisure

- Growth and development of the crea-tive ability of the child through suchforms of expression as music, drama,and crafts

D Provision of a program of activitiessufficiently broad and of such nature asto provide many of the basic satisfac-tions that children must have to beemotionally stable, mentally adaptable,and socially effective

D Development of a sense of achieve-ment and individual worth by pro-viding numerous and varied oppor-tunities for the attainment of successin recreational activities and bestow-ing the recognition which such suc-cess merits

Educational Leadership

D Development of such qualities as co-operation, courtesy, respect for au-thority, fair play, respect for the rightsof others, and willingness to accept re-sponsibility as one of a social group.

Commenting on these objectives, thedirector of the program says, "It is notenough to provide activities for youthwithout regard to what happens tothem while they are participating. Wecannot afford to evaluate our programson the basis of numbers taking part.We must be concerned with the qualityof recreational experience and its effectupon the behavior of those who experi-ence it.

"No attempt is made to standardizethe programs in the various centers.They grow out of the needs of chil-dren and represent the interests andcharacter of the different neighbor-hoods from which the children come.The recreation leader for these pro-grams is chosen carefully, to assureguidance and leadership in keeping withthe philosophy underlying the objec-tives."

A Community Uses What It HasIn an east coast community, parent

and school staff, recognizing the facili-ties which the schools had to offer,asked that these facilities be utilizedduring the summer months for the chil-dren. A day camp program was putinto operation, using school buildingswhich were located in neighborhoodswhich offered no parks, swimmingpools, or even limited recreational fa-cilities. These areas were found to beneighborhoods in which both parents,in many cases, were employed and chil-dren were left with too much leisureand little guidance and supervision.

March 1948

Unlimited Activity PossibilitiesThe summer program involved co-

operative planning on the part of par-ents, teachers, principals, and adminis-trative staff from the beginning. Ameeting was called to explore the needand to discuss the desirability of theschools offering a vacation programfor children. The Board of Educationwas requested to grant funds for a sum-mer day camp program. Brief sketchesfrom the program report suggest thevaried and worthwhile learning experi-ences which the summer camp centersprovided:0 At Camp #zz a playground was

planned, constructed, maintained,and enjoyed by the children and thecommunity. A dump adjoining thecamp was cleared. Several tons ofcement donated by the Board ofEducation was leveled for a smoothsurface. Flower boxes were madeand filled to decorate the plot. Ashower and sand box were givenby the Board of Education.

I Camp newspapers at two centersproved a successful medium forcreative writing and served to builda feeling of solidarity among themembers of the centers.

P Trips were an outstanding featureof the summer activities. Each cen-ter moved abroad in the communityas interest and facility dictated.Among the places visited were thezoo, art center, a splash party at the"Y," straw ride to a farm, a boattrip, a weiner roast, and an over-night camp at the director's farm.

P Children love to pretend! A room,a box of costumes, a group of undis-turbed children resulted in somefine dramatic plays in the Little

381

Theater. These productions were

often planned and staged by the

children without parts to be learnedor formal rehearsals.

0 The children made equipment such

as blocks, drums, dolls, a trip book,sketch book, badges to wear on trips

for identification, camp signs, toys,

stage properties, hobby horses, and

airplane models.

Benefits Shared by Al

Individuals with special interests in

the arts, dramatics, dancing, music,

gymnasium, library, and crafts divided

their days among the centers. Parents

and others in the community with

special interests shared responsibilitieswith the groups at varying hours

throughout the day. The leaders provedto their satisfaction that the environ-ment influences the quality of learning.

In each center every effort was made

to make the program so attractive, so

pleasant, and so appealing as to be ir-

resistible to children.Wherever one looked there was

something to admire, something which

gave pleasure to look at, to touch, or

just absorb. Schoolrooms with their ar-

bitrary furniture and proportionsweren't always easy to handle, but they

could be modified. School furniturewas removed or stacked away in a cor-

ner. Bright sofa cushions and benches

appeared. Lovely flower arrangementsand colorful ornaments were used. Wall

hangings covered blackboards. Toys and

books were accessible. Informality,aesthetic appeals, a variety of materials,

and homelike living predominated.Teachers, children, parents, and com-

munity benefited from the summer

school camp. Children grew as socialized

382

members of a mixed society. Adultsmatured in thier knowledge of how tolive and work with children effectively.The whole community profited in theunderstanding relationships which thisenvironment fostered.

No Monopoly on OpportunityWhat these communities are doing

is also within the reach of every com-munity. The cost of operating a recrea-tional program for children during out-of-school hours is not as great as mightbe expected. Often the school with itsequipment, rooms, and grounds remainsidle too large a proportion of time.

In the summer months the buildingrequires no heat, and children can as-sume their share in keeping the schoolin order. During the winter the build-ing will be heated during most of theday. For the additional hour or morein the afternoon, some extra expensewill be involved for the longer day, orthe longer week if a Saturday programis offered. However, when the cost ismeasured in terms of the effects ofsuch a program on improving the liv-ing of children and the community,there can be no question as to the valuesof such an investment in children.

Special Leadership Qualities Required

Finally, it should be said that a schoolrecreational program will stand or fallon the quality of leadership provided.Paid leaders are essential to give stabil-ity to the program. If the program isto function on a sound education base,skillful teachers who like and under-stand children must be found to guidechildren's activities in each center.Those experienced in operating out-of-school programs for children say they

Educational Leadership

have found it necessary to select maturepersons as leaders, who have a zest forliving and who possess ingenuity andresourcefulness in developing a pro-gram.

New Emphasis in Teacher EducationAs schools move toward the establish-

ment of a year-round program for chil-dren, teacher education programs willneed to be re-examined and reshaped inthe light of the type of recreationalservices which schools offer. Fewteacher education institutions now givestudents the background and experi-ences which teachers need to work withchildren in a leisure-time program.More attention should be directed tohelping a teacher know about the play

interests of the older child, and howthe child probes his world for answersto his questions. He should also haveexperience in working with parents sothat he can accept them as partners inthe educative process both at home andat school.

Finally, the teacher should be ac-quainted with the community agencies,know what resources are available, andhow they can be utilized in a recrea-tional program. Libraries, museums,churches, and youth organizations areconcerned and interested in the con-structive use of leisure time. Theirservices and those of the schools shouldbe coordinated to strengthen and en-rich the programs for children in eachcommunity.

Aeontz Suides to

FRED V. HEIN

In our concern for providing desirable environments for children wecannot overlook aspects that make the environment a healthful one inwhich to live. Fred V. Hein, consultant in Health and Fitness, Bureauof Health Education of the American Medical Association, Chicago,points out that both physical aspects and classroom practices affect thetotal health of children.

THE GROWTH and development ofboys and girls is conditioned by the kindof school they attend as well as everyother aspect of their environment.Good physical surroundings, whiole-some teacher personalities, and under-standing administration can, together,

March 1948

create a school situation that is safe andhealthful for living and learning.

Determiners of the Learning ClimateSuitable equipment, adequate lighting

and heating, proper ventilation, and at-tractive and restful surroundings not

383

Copyright © 1948 by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. All rights reserved.