Hartz Companion Animal - Wolbachia and Heartworm Disease

-

Upload

the-hartz-mountain-corporation -

Category

Lifestyle

-

view

616 -

download

7

description

Transcript of Hartz Companion Animal - Wolbachia and Heartworm Disease

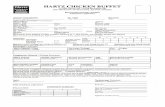

Dirofilaria immitis is the causative agentof canine and feline heartworm disease.Adult worms live in the pulmonaryarteries, and females produce first-stagelarvae (microfilariae), which are taken upby mosquitoes that then transmit theinfection to other animals. In dogs, anuntreated infection leads to congestiveheart failure (Figures 1 and 2). D. immitis,like most filarial worms studied to date,harbor bacteria called Wolbachia, which arethought to play an essential role in thebiology and reproductive functions of theirfilarial hosts. Wolbachia pipientis, the onlyspecies thus far identified in the genus,are gram-negative bacteria belonging to the order Rickettsiales (just like Ehrlichiaspp and Anaplasma spp).1 In adult D.immitis, Wolbachia is predominantly foundthroughout cells in the hypodermis, whichis directly under the worm’s cuticle (Figure3). In female D. immitis, Wolbachia is alsopresent in the ovaries, oocytes, and

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE:

Deworming Demystified............ 4

Wolbachia increases its own fitness byincreasing the fitness of the hostinvolved in its transmission.

� Removal of Wolbachia (via antibioticsor radiation) leads to sterility of femaleworms and eventual death of adults.

It is still unclear, however, exactly whatWolbachia does to make it so importantfor its filarial host. It has been suggestedthat, while the filarial worm likely suppliesthe bacteria with amino acids necessaryfor growth and replication, Wolbachia mayproduce several important molecules thatare essential for heartworms, such asglutathione and heme.2 It is indeed a “onehand washing the other” situation that

S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 6 V O L U M E 4 , N U M B E R 3

developing embryonic stages within theuteri. This suggests that the bacterium isvertically transmitted through thecytoplasm of the egg.1

ROLE OF WOLBACHIA IN ITS FILARIAL HOST

Human research has revealed severalreasons why the presence of Wolbachia isthought to be essential for a filarialworm’s survival:

� In those species of filarial worms thathave been identified as harboringWolbachia, all of the individuals areinfected (i.e., 100% prevalence).

� The evolution of the bacteria matchesthat of the filarial worms, andphylogenic studies have shown thatthe two organisms have been “walkinghand-in-hand” for millions of years.

� The bacteria are transmitted fromfemale to offspring and, in this way,

Wolbachia andHeartworm DiseaseLaura H. Kramer, DVM, PhD, DEVPCCollege of Veterinary MedicineUniversity of Parma, Parma, Italy

A NEWSLETTER OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE FOR VETERINARY PROFESSIONALSA NEWSLETTER OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE FOR VETERINARY PROFESSIONALS

2 HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • SEPTEMBER 2006 • VOL. 4, NO. 3

Consulting EditorsAlbert Ahn, DVM

Vice President of CorporateCommunications and ConsumerRelationsThe Hartz Mountain Corporation

Bruce TrumanSenior DirectorAnimal Health and NutritionThe Hartz Mountain Corporation

Associate EditorsJill A. Richardson, DVM

DirectorConsumer RelationsThe Hartz Mountain Corporation

David LevyAssistant ManagerAnimal Health and NutritionThe Hartz Mountain Corporation

HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM

is produced for The Hartz Mountain Corporation by Veterinary Learning Systems, 780 Township Line Rd.,Yardley, PA 19067.

Copyright © 2006 The Hartz Mountain Corporation. All rights reserved.

Hartz® and other marks are owned byThe Hartz Mountain Corporation.

Printed in U.S.A. No part of thispublication may be reproduced in anyform without the express writtenpermission of the publisher.

For more information on The HartzMountain Corporation, visitwww.hartz.com.

S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 6 V O L U M E 4 , N U M B E R 3

A NEWSLETTER OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE FOR VETERINARY PROFESSIONALS

may, however, be the key to novelstrategies for the control/treatment offilarial infection, including canine andfeline heartworm disease.

ROLE OF WOLBACHIA IN THE INFLAMMATORY ANDIMMUNE RESPONSE IN D.IMMITIS–INFECTED ANIMALS

As gram-negative bacteria, Wolbachiahave the potential to play an important rolein the pathogenesis and immune responseto filarial infection. The possibleconsequences of the massive release ofWolbachia in the filaria-infected host havebeen evaluated. Wolbachia are released bothby living worms and after worm deaththrough natural attrition, microfilarialturnover, and pharmacologic intervention.3

In human and murine models of infection,the release of bacteria has been shown tobe associated with the up-regulation ofproinflammatory cytokines, neutrophilrecruitment, and an increase in specificimmunoglobulins. Ongoing studies in dogswith heartworm disease may shed light onwhat happens when infected animals comeinto contact with the bacteria. For example,my colleagues and I recently tested thehypothesis that D. immitis–infected dogscome into contact with Wolbachia eitherthrough microfilarial turnover or naturaldeath of adult worms.4 In our study,positive staining for Wolbachia wasobserved in various tissues from dogs thathad died because of natural heartworm

disease. Bacteria were observed in the lungs and particularly in organs wheremicrofilariae normally circulate, such as thekidney and liver. Furthermore, when welooked at specific antibody responses toWolbachia, we observed a stronger responsein dogs with circulating microfilariaecompared with dogs with occult infection,supporting the hypothesis that microfilarialturnover is an important source ofWolbachia in dogs with heartworm disease.Furthermore, Wolbachia from D. immitishave been shown to provoke chemokinesisand proinflammatory cytokine productionin canine neutrophils. Cats withheartworm disease also produce antibodiesto Wolbachia. Interestingly, it has recentlybeen reported that the development of astrong antibody response against D. immitisoccurs after 1 to 2 months of infection,which has important implications for earlydiagnosis.5

Areas of future research should includethe possible diagnostic use of specificimmune responses to Wolbachia, itspotential immunomodulatory activity(prevention), and the effects of antibiotictreatment in infected animals.

EFFECT OF ANTIBIOTICTREATMENT ON FILARIALWORMS

Wolbachia can be eliminated fromfilarial worms through antibiotic therapyof the infected host. Numerous studieshave shown that various treatmentprotocols and dosages (tetracycline and

synthetic derivatives appear to be themost effective) are able to drasticallyreduce if not completely remove theendosymbiont from the worm host. Suchdepletion of Wolbachia is then followed byclear antifilarial effects, including:

� Inhibition of larval development:It has been shown that antibiotictreatment of filaria-infected hosts can

Figure 1. A 6-year-old Great Danewith chronic heartworm disease. Note theweight loss (apparent by the noticeablespine and rib cage) and dilated abdomen(due to ascites). (Photo by Dr. Luigi Venco)

Figure 2. Radiograph of the dog in Figure 1. Note the enlarged cardiacchambers (white arrows), thickenedpulmonary arteries (yellow arrow), andinterstitial inflammation. (Photo by Dr. LuigiVenco)

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR ADULTICIDETHERAPY—WOLBACHIA

Most filarial nematodes, including D. immitis, harbor obligate, intracellular, gram-negative bacteria belonging to the genus Wolbachia (Rickettsiales). In infections with otherfilarial parasites, treatment with tetracyclines during the first month of infection was lethalto some Wolbachia-harboring filariae but not to a filariae that did not harbor Wolbachia,and treatment of Wolbachia-harboring filariae suppressed microfilaremia. Similarprophylaxis studies with D. immitis have not been reported, but in one study, tetracyclinetreatment of heartworm-infected dogs resulted in infertility in the female worms. Thesebacteria also have been implicated in the pathogenesis of filarial diseases, possibly throughtheir endotoxins. Recent studies have shown that a major surface protein of Wolbachia(WSP) induces a specific IgG response in hosts infected by D. immitis. It is hypothesizedthat Wolbachia contribute to pulmonary and renal inflammation through the surfaceprotein WSP independent of its endotoxin component. Studies to determine the effects of suppressing Wolbachia populations with doxycyline prior to adulticide therapy will berequired to determine the clinical utility of this therapeutic approach.

From: Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Prevention and Management of Heartworm (Dirofilaria immi-tis) Infection in Dogs; reprinted with permission of the American Heartworm Society. Availableat www.heartwormsociety.org; accessed August 2006.

inhibit molting, an essential processin the maturation of worms fromlarvae to adult.

� Female worm sterility: Antibiotictreatment leads first to a reductionand then to the complete andsustained absence of microfilariae.Researchers at the University ofMilan, Italy, have reported that D.immitis adults taken from naturallyinfected dogs that had been treatedwith doxycycline at 20 mg/kg/day for 30 days showed morphologicalterations of uterine content with adramatic decrease in the number ofmature microfilariae, indicating thatbacteriostatic antibiotic treatment was able to block embryogenesis.6

� Adulticide effects: This is a particularlyintriguing aspect of antibiotic treatmentof the filarial worm–infected host andone that merits strict attention. Clinicaltrials in human filariasis have reportedextremely promising results: A recentplacebo-controlled trial in humansinfected with Wuchereria bancrofti hasdemonstrated a clear macrofilaricidal(i.e., adulticidal) effect of doxycycline.7

When administered for 8 weeks at 200mg/day, doxycycline treatment resultedin complete amicrofilaremia in 28 of 32patients assessed and a lack of wormnests in the scrotum (where adultworms reside) at 14 months aftertreatment, as determined by

ultrasonography in 21 of 27 patients.In the other patients, the number ofscrotal worm nests declined. This wassignificantly different from placebopatients in which lack of worm nestswas only observed in three of 27patients. This is the first report ofantibiotic-induced adulticide activity in a human filarial worm. Couldantibiotic treatment have the sameeffect on D. immitis? Several researchgroups, including our laboratory, arecurently attempting to answer this veryimportant question.

EFFECTS OF ANTIBIOTICTREATMENT ON THE FILARIALWORM–INFECTED HOST

It is very likely that antibiotic treatmentwill have some beneficial effects on subjectswith filariasis. First, the effects on theworm (described above) will themselveslead to improved clinical presentation,such as a reduction in the circulatingmicrofilariae that have been implicated inimmune complex formation duringinfections.4 However, if Wolbachia isconsidered a potential cause ofinflammation in the course of filarialdisease, depletion of the bacteria may bebeneficial independent of its effect on the

worm. There are little data concerning theeffects of antibiotic treatment in dogs withnatural heartworm disease; what is known,however, is that such treatment drasticallyreduces Wolbachia loads in D. immitis.Preliminary trials8 in naturally infecteddogs have shown that doxycycline treatmentbefore adulticide therapy with melarsominemay help reduce proinflammatory reactionsdue to the death of adult worms (as seenby lower antibody levels against Wolbachiaand lower levels of interleukin-8, aninflammatory cytokine involved inneutrophil recruitment). These results haveencouraged our laboratory to continue toevaluate the clinical benefits of antibiotictreatment in naturally infected dogs.

Given the recent and very promisingdevelopments in the use of tetracyclinesfor micro- and macrofilaricidal therapy inhuman filariasis, it is hoped that similarattention will be given to canine andfeline heartworm disease, which couldgreatly benefit from alternativetherapeutic strategies.

REFERENCES1. Bandi C, Trees AJ, Brattig NW: Wolbachia in filarial

nematodes: Evolutionary aspects and implications forthe pathogenesis and treatment of filarial diseases. VetParasitol 98:215–238, 2001.

2. Foster J, Ganatra M, Kamal I, et al: The Wolbachiagenome of Brugia malayi: Endosymbiont evolution

(continues on page 8)

Figure 3. Cross–section of an adultfemale Dirofilaria immitis stained with apolyclonal antibody against the Wolbachiasurface protein. Note the numerousbacteria (arrows) that almost entirely fillthe cell of the lateral hypodermal cord.(Original magnification x40)

HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • SEPTEMBER 2006 • VOL. 4, NO. 3 3

4 HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • SEPTEMBER 2006 • VOL. 4, NO. 3

Parasites are important causes ofdisease in dogs and cats of all ages (Table1) but can be particularly important inpuppies and kittens because of their smallsize, developing immunity, and otherstresses associated with growth andmaturation. Young pets are often exposedto and acquire parasites differently thanolder pets. Because of their increasedexposure and susceptibility, they oftenharbor greater numbers of parasites thanmature animals. Heavier parasite burdensplace puppies and kittens at greater risk ofdisease and also lead to higher sheddingrates of fecal stages into the environment.Increased environmental contaminationalso increases the risk of human exposureto zoonotic roundworms and hookworms.This article reviews strategies fordeworming dogs and cats. Availableparasiticides now allow importantparasites to be eliminated safely and pets to be maintained free of parasitesthroughout their lives.

SOME DEWORMINGDEFINITIONS

Several terms have been used to definethe various approaches to internal parasitecontrol and the available parasiticides.Deworming terms include “strategic,”“discretionary,” “targeted,” and “interval,”and parasite control products are identifiedas single entity (one active ingredient),combination (more than one activeingredient), narrow spectrum (products thatare capable of removing one or twoparasites), and broad spectrum (products

Deworming Demystified:Update on Deworming ProtocolsByron L. Blagburn, MS, PhDDistinguished University ProfessorDepartment of PathobiologyCollege of Veterinary MedicineAuburn University

Discretionary DewormingDiscretionary deworming is based on a

perceived need to deworm, such as resultsof fecal examination or other diagnostictests (e.g., elevated eosinophil count,radiographic evidence of pulmonaryparasitism). As the name implies,discretionary deworming is performed atthe discretion of the veterinarian. In myview, discretionary deworming should beperformed only based on knowledgegained from history or presenting signs,appropriate diagnostic procedures, orother information sufficient to warrantthe use of parasiticides.

Targeted DewormingTargeted deworming, in my opinion,

is just another term for strategicdeworming. The intent is to “target”particular time points based on criteriamentioned above for strategic deworming(i.e., age, environment, history of priorparasitism or exposure to parasites, andgeographic region).

Interval DewormingInterval deworming is deworming

pets at specific intervals. The approach is similar to strategic or targeteddeworming, but with less attention givento specific reasons for selecting timepoints. Interval deworming is usuallyintended to provide a “safety net,” basedon the presumption that pets are likely to be exposed to parasites but withoutspecific knowledge of when that exposureis likely to occur.

that can eliminate many parasites, oftenincluding both internal and externalparasites) (Table 2). The language becomeseven more confusing when one considersthat some single-entity products havebroad-spectrum activity (e.g., pyrantelpamoate, milbemycin oxime) and thatcombining products may or may notincrease the spectrum of internal parasiteseliminated (e.g., ivermectin–pyrantelpamoate versus milbemycin oxime–lufenuron).

Strategic DewormingStrategic deworming is the application

of a specific parasite-control strategybased on an individual pet’s age,environment, and likelihood of exposureto parasites, prevalence of the parasite inquestion, and geographic region. Anexample of strategic deworming would bedeworming puppies at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks of age to control migrating stagesof roundworms and hookworms(discussed below). Additional examplesinclude strategically placed intervalsbetween dewormings throughout the year,such as every 6 months or every 3 monthsfor pets with a seasonal likelihood ofexposure to parasites or if control of aspecific parasite, such as whipworm, isneeded. Strategic deworming may alsoinclude a strategy of monthly, year-round,broad-spectrum internal parasite controlto improve compliance and takeadvantage of heartworm preventives or flea-control products with activityagainst important internal parasites.

puppies and kittens requires a strategy toeliminate parasites as they mature. Boththe Companion Animal Parasite Council(CAPC; www.capcvet.org) and the Centersfor Disease Control and Prevention (CDC;www.cdc.gov) recommend dewormingpuppies beginning at 2 weeks of age andcontinuing every 2 weeks through 8 weeksof age; thereafter, puppies can be placedon monthly broad-spectrum agents thatinclude heartworm and/or flea control andalso possess activity against roundworms

SPECIFICRECOMMENDATIONSPuppies and Kittens

Parasite control in puppies and kittenspresents several unique challenges; someare the result of parasite behavior, whereasothers are the result of host factors andparasiticidal efficacy. Roundworms andhookworms, the most common parasitesof young pets, are acquired throughseveral routes: embryonated eggs, milk orcolostrum, via the uterus and placenta,

and by ingestion of paratenic (transport)hosts (Table 1). Both roundworms andhookworms may undergo multisystemmigrations in puppies and kittens.Continual infection via multiple routesand multisystemic migration lead to thepresence of parasites in different stages indifferent organ systems during theirmigrations. Because current parasiticidesare most effective in eliminating the adultstages of roundworms and hookworms inthe intestine, control of these parasites in

HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • SEPTEMBER 2006 • VOL. 4, NO. 3 5

TABLE 1: Common Nematode Parasites of Dogs and Cats

Parasite(Common Name) Host(s)

Prevalence/Geographic

Location

Site ofDevelopment(Adult Worms) Life Cycle

DevelopmentalPeriod

Diagnostic Procedure/Stage in Feces

ZoonoticPotential

Toxocara canis(canineroundworm)

Dogs High/throughout

the US

Smallintestine

Infection by embryonated eggsand transplacental transmission;larvae undergo liver–lungmigration; rodents may serve astransport hosts; transmammarytransmission is uncommon

28–35 days Fecal flotation/non-embryonated eggs are 90 × 75 µm,subglobular, withthick pitted shells

Veryhigh

Toxocara cati(felineroundworm)

Cats High/throughout

the US

Smallintestine

Direct infection by embyronatedeggs and transmammarytransmission; rodents may serveas transport hosts; larvae mayundergo liver–lung migration;transplacental transmissionapparently does not occur

38–56 days Fecal flotation/non-embryonated eggs

are 65–75 µm;similar to T. caniseggs but smaller

Veryhigh

Toxascarisleonina(nonmigratoryroundworm)

Dogsandcats

Low/throughout

the US;distribution

spotty

Smallintestine

Direct infection by embryonatedeggs; rodents may serve astransport hosts; development isrestricted to small intestine; noextraintestinal, transplacental, ortransmammary transmission

74 days Fecal flotation/non-embryonated eggs are 80 × 70 µm,

slightly oval with asmooth shell

None

Ancylostomacaninum (caninehookworm)

Dogs High/throughout

the US; morecommon in

warmerclimates

Smallintestine

Direct infection by ingestion orskin penetration; may undergolung migration; ingested larvaemay mature without lungmigration; rodents may serve astransport hosts; the principal routeof infection is transmammary

15–18 days Fecal flotation/non-embryonated eggsare 70 × 40 µm

High

Ancylostomatubaeforme(felinehookworm)

Cats High/throughout

the US; morecommon in

warmerclimates

Middle smallintestine

Direct infection by ingestion orskin penetration; larvae mayundergo lung migration; rodentsmay serve as transport hosts; notransmammary or transplacentaltransmission

16–25 days Fecal flotation/non-embryonated eggs are 61 × 40 µm

Low

Ancylostomabraziliense(subtropicalhookworm)

Dogsandcats

High in tropicaland subtropicalregions/limitedto Florida and

Golf Coast

Anteriorsmall

intestine

Direct infection by ingestion orskin penetration; larvae mayundergo lung migration; rodentsmay serve as transport hosts; noinformation on transmammaryor transplacental transmission

14–27 days Fecal flotation/non-embryonated eggs

are 55 × 34 µm; noteasily differentiatedfrom A. tubaeforme

High

Trichuris vulpis(whipworm)

Dogs High/throughout

the US

Cecum Direct infection by ingestion ofembryonated eggs

77–84 days Fecal flotation/non-embryonated eggs

are brownish, bipolar,and 80 × 30 µm

Notthoughtto be

zoonotic

6 HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • SEPTEMBER 2006 • VOL. 4, NO. 3

and hookworms (Table 2). This monthlystrategy serves two purposes—it helpsimprove pet owner compliance andprovides continuous roundworm andhookworm control. It should be notedthat only pyrantel pamoate can be used in puppies as young as 2 weeks; otheravailable agents can be used in puppiesand kittens starting at 3 to 4 weeks of age.

If monthly broad-spectrum controlstrategies are not used, an alternativestrategy of biweekly deworming from 2 to 8 weeks of age followed by monthlydeworming through 6 months of age canbe employed. Because of the differences in the life cycles of canine and felineroundworms, kittens can be treatedbiweekly between 3 and 9 weeks and then placed on broad-spectrum agents or treated monthly for 6 months as

described for puppies. If pets are notmaintained on monthly broad-spectrumagents, annual or semiannual fecalexaminations using centrifugal flotationshould be performed. Appropriatetreatments should then be administeredbased on results of fecal examinations(discretionary deworming).

It is important to remember that petsare susceptible to and may harbor parasitesthat are not eliminated by broad-spectrumheartworm preventives. Examples includetapeworms, coccidia, and Giardia. Theseand other parasites drive the need foraccurate fecal examinations conducted atregular intervals. The frequency of fecal examinations (e.g., one to fourtimes/year) varies based on the age of the pet, prior infection status, andpotential exposure.

Adult Dogs and CatsSurveys indicate that dogs and

cats remain susceptible to parasitesthroughout their lives, although the riskof disease diminishes somewhat as petsage. Adult dogs and cats are also lesslikely to harbor burdens of intestinalroundworms and hookworms that are as large as is seen in puppies or kittens.A number of strategies have beenemployed to control parasitic infectionsin adult pets. Among them are continualmonthly administration of broad-spectrum heartworm preventives; annual,semiannual, or quarterly use of broad-spectrum dewormers; and discretionarydeworming based on results of fecalexaminations. The strategy ofcontinuous monthly use of broad-spectrum heartworm products is often

Chemical Name Product NameHost Species:Parasites Removed Dosage/Regimen Minimum Age

Pyrantelpamoate

Hartz® Advanced Care™ Rid Worm™Chewable Flavored Wormer Tablets;Nemex™, Nemex™-2 (Pfizer AnimalHealth); many others

Dog: TC, TL, AC, US 5 mg/kg

Discretionary treatment

No minimum age

Pyrantelpamoate–praziquantel

Drontal® (Bayer Animal Health) Cat: Tca, AT, DC, TT 5 mg/kg praziquantel and 20 mg/kg pyrantel pamoate

Discretionary treatment

4 wk and >1.5 lb

Fenbendazole Panacur® C Canine Dewormer(Intervet)

Dog: TC, TL, AC, US, TV 50 mg/kg/day for 3 days

Discretionary treatment

6 wk

Febantel–pyrantelpamoate–praziquantel

Drontal® Plus (Bayer Animal Health) Dog: TC, TL, AC, US, TV, DC, TP, EG, EM

10 mg/kg febantel, 5 mg/kgpyrantel pamoate, and 5mg/kg praziquantel

Discretionary treatment

3 wk and >2 lb

Ivermectin Heartgard® Chewables for Cats Cat: DI (L3/L4), AT, AB 24 µg/kg q30d 6 wk

Ivermectin–pyrantelpamoate

Heartgard® Plus Chewables for Dogs;Iverhart™ Plus Flavored Chewables(Virbac); Triheart® Plus ChewableTablets (Schering-Plough Animal Health)

Dog: DI (L3/L4), TC, TL, AC,AB, US

6 µg/kg ivermectin and 5 mg/kg pyrantel pamoateq30d

6 wk

Milbemycinoxime

Interceptor® Flavor Tabs® for Dogsand Cats (Novartis)

Cat: DI (L3/L4), Tca, AT

Dog: DI (L3/L4), TC, TL, AC, TV

Cat: 2.0 mg/kg q30d

Dog: 0.5 mg/kg q30d

Cat: 6 wk or >1.5 lb

Dog: 4 wk or >2 lb

Milbemycinoxime–lufenuron

Sentinel® Flavor Tabs® (Novartis) Dog: DI (L3/L4), TC, TL, AC,TV, eggs of CF

0.5 mg/kg milbemycin oximeand 10 mg/kg lufenuron q30d

4 wk or >2 lb

Selamectin Revolution® (Pfizer Animal Health) Cat: DI (L3/L4), Tca, AT

Dog: DI (L3/L4), CF, SS, OC, DV

6 mg/kg q30d Cat: >8 wk

Dog: >6 wk

AB = Ancylostoma braziliense; AC = Ancylostoma caninum; AT = Ancylostoma tubaeforme; CF = Ctenocephalides felis; DC = Dipylidium caninum; DI = Dirofilaria immitis; DV =Dermacentor variabilis; EG = Echinococcus granulosus; EM = Echinococcus multilocularis; L3 = third-stage larvae; L4 = fourth-stage larvae; OC = Otodectes cynotis; SS = Sarcoptes sca-biei; TC = Toxocara canis; Tca = Toxocara cati; TL = Toxascaris leonina; TP = Taenia pisiformis; TT = Taenia taeniaeformis; TV = Trichuris vulpis; US = Uncinaria stenocephala.

TABLE 2: Selected Broad-Spectrum Canine and Feline Internal Parasiticides

IMPORTANT NEWS FROM HARTZ®

Dear Veterinarian:

This spring, The Hartz Mountain Corporation, one of the leading providers of flea and tick products in the nation, introduced

a new topical insecticide product called Hartz® UltraGuardplus™ Drops for Cats. The product is registered by the US

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for use on cats and kittens over 12 weeks of age, and it will be available in retail

stores nationally in the weeks ahead.

Our goal is the same as that of the veterinary community – to make sure that all pets are protected from harmful fleas and

ticks. We are committed to offering effective, well-tested products that can support and supplement the care provided by

veterinarians. Surveys routinely show that millions of Americans use no flea and tick protection on their pets. Hartz®

UltraGuardplus™ Drops for Cats offers an economical alternative for pet owners and may help expand the number of

companion animals that are protected from ectoparasites.

Well-tested active ingredients

Hartz® UltraGuardplus™ Drops for Cats contains an all-new formula that combines a well-tested adulticide, Etofenprox,

and an insect growth regulator (IGR), (S)-Methoprene. This product offers consumers an effective, once-a-month topical

treatment that works quickly to kill fleas, flea eggs, deer ticks, and mosquitoes.

Etofenprox has been registered by governments around the world to protect food crops from insect pests1. The insecticide

received its first EPA registration for use on pets in 2004 and is an active ingredient in another, currently available feline

topical product2. Etofenprox is a completely different insecticide from the one used in former Hartz® feline topicals

(phenothrin).

The IGR in Hartz® UltraGuardplus™ Drops for Cats is (S)-Methoprene, which has a long history of effective use.

(S)-Methoprene has been used for more than 20 years to fight infestations of fleas, mosquitoes, flies, ants, and other insects3.

In order to receive EPA registration, the Hartz® UltraGuardplus™ Drops for Cats formulation underwent the same series

of efficacy, safety, and acute toxicity tests required for all insecticidal products used on animals, including veterinary flea

and tick products. Through the acute toxicity tests, the formulation was determined to be in the EPA’s lowest acute toxicity

category (Category IV - 40 CFR 156.62).

As you know, even with excellent study results, any insecticide product can produce adverse events in sensitive felines. An

important element of our commitment to flea and tick protection is an ongoing effort to educate pet owners about these

health issues and the importance of using flea and tick products appropriately. Hartz® publicizes these important messages in

advertising, consumer brochures, our websites and other outreach efforts.

While Hartz® seeks to minimize the chance of any adverse event in pets, should they occur, we urge veterinarians to report

any incident to us. Veterinarians and pet owners can contact Hartz® Consumer Relations 24 hours a day, seven days a week

at 1-800-275-1414 for answers to their questions and other support.

Sincerely,

Jill Richardson, DVM

Director, Consumer Relations and Technical Services

1 PAN Pesticides Database. http://www.pesticideinfo.org/Detail_Chemical.jsp?Rec_Id=PC33231

2 Sergeant’s news release. Available at www.sergeants.com/news_events/press.asp?prm_id=568

3 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency fact sheet. Available at www.epa.gov/oppbppd1/biopesticides/ingredients/factsheets/factsheet_igr.htm

within a human pathogenic nematode. PLoS Biology3:e121–129, 2005.

3. Taylor MJ, Cross HF, Ford L: Wolbachia bacteriain filarial immunity and disease. Parasite Immunol23:401–409, 2001.

4. Kramer LH, Tamarozzi F, Morchon R, et al:Immune response to and tissue localization of theWolbachia surface protein (WSP) in dogs with naturalheartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) infection. Vet

endosymbionts Wolbachia. Int J Parasitol 29:357–364, 1999.

7. Taylor MJ, Makunde WH, McGarry HF, et al:Macrofilaricidal activity after doxycycline treatmentof Wuchereria bancrofti: A double-blind, randomisedplacebo-controlled trial. Lancet 365:2116–2121,2005.

8. Kramer L: Treating canine heartworm infection.NAVC Clin Brief May:17–18, 2006.

Immunol Immunopathol 106(3–4):303–308, 2005.5. Morchon R, Ferreira AC, Martin-Pacho J, et al:

Specific IgG antibody response against antigens ofDirofilaria immitis and its Wolbachia endosymbiontbacterium in cats with natural and experimentalinfections. Vet Parasitol 125:313–321, 2004.

6. Bandi C, McCall JW, Genchi C, et al: Effects oftetracycline on the filarial worms Brugia pahangiand Dirofilaria immitis and their bacterial

WOLBACHIA AND HEARTWORM DISEASE (continued from page 3)

Veterinary Learning Systems780 Township Line RoadYardley, PA 19067

PRST STDU.S. POSTAGE

PAIDYORK, PA

PERMIT #200

402344

implemented in regions whereheartworm prevention is necessary for allor most of the year. Veterinarians muststill conduct fecal examinations to assurethat selected parasiticides are effectivelycontrolling parasites. It is sometimesnecessary to supplement monthly broad-spectrum heartworm preventives withother control strategies using additionalparasiticides based on results of fecalexaminations.

Pregnant bitches and queens are alsomore susceptible to certain parasitesduring the periparturient period. Thesepets should either remain on broad-spectrum preventives throughoutpregnancy and lactation or they should bedewormed at the same time their offspringare dewormed during the postparturientperiod. Veterinarians can consult withacademic parasitologists regardingstrategies for eliminating tissue reservoirs

parasiticides can then be administered as necessary. Annual fecal examinationsand discretionary use of parasiticides areespecially important in senior pets that are not receiving monthly broad-spectrumagents.

SUGGESTED READINGBlagburn BL: Prevalence of canine parasites based on

fecal flotation. Compend Contin Educ Vet 18:483–509,1996.

Blagburn BL, Butler J: Optimize intestinal parasitedetection with centrifugal fecal flotation. Vet MedJuly:455–464, 2006.

Fisher M: Toxocara cati: An underestimated zoonoticagent. Trends Parasitol 19:167–170, 2003.

Kalkofen UP: Hookworms of dogs and cats. Vet ClinNorth Am Small Anim Pract 7(6):1341–1354, 1987.

Marty AM: Toxocariasis, in Meyers WM, Neafie RC,Marty AM, Wear DJ (eds): Pathology of InfectiousDiseases. Washington, DC, American Registry ofPathology, 2000, pp 411–421.

Nolan TJ, Smith G: Time series analysis of theprevalence of endoparasitic infections in cats anddogs presented to a veterinary teaching hospital. VetParasitol 59:87–96, 1995.

of ascarids and hookworms from breedingbitches. These strategies require intenseuse of available parasiticides during thegestation period and should be used onlyafter consulting with qualified experts.

Senior PetsModern parasiticides are safe and

effective for use in older pets, includingthose with other illnesses. In regionswhere heartworms remain prevalentthroughout most of the year, continuoususe of broad-spectrum agents remains a popular strategy. Periodic fecalexaminations are necessary in senior petsnot only because they remain susceptibleto parasites but also because other healthconditions may make them morevulnerable to the effects of parasites.Senior pets should be examined at leastannually using a sensitive centrifugal fecalflotation procedure. Appropriate

DEWORMING DEMYSTIFIED (continued from page 6)