Hartz Companion Animal - (S)-Methoprene: Chemical Properties and Applications for Effective Flea...

-

Upload

the-hartz-mountain-corporation -

Category

Lifestyle

-

view

1.075 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Hartz Companion Animal - (S)-Methoprene: Chemical Properties and Applications for Effective Flea...

Successful control of both pet andenvironmental flea infestations continuesto challenge the most conscientious ofveterinarians and pet owners. Not onlyare newer flea-control agents moreeffective and much safer than traditionalagents, they are often available inconvenient formulations. Althougheffective products are the basis ofsuccessful flea programs, other factors,such as pet–owner compliance, climate,rates of environmental contamination andflea challenge, pet-owner perceptions ofthe severity of the flea problem, andperhaps resistance, can affect our abilityto eliminate fleas from pets and theirenvironments successfully.

The developmental cycle of fleas(including Ctenocephalides felis, thecommon flea of cats and dogs)comprises several distinct stages

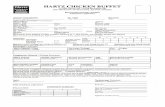

IN THIS ISSUE:(S)-Methoprene: Chemical Properties and Applications for Effective Flea Control........... 1The American Kennel ClubWelcomes the Glen of Imaal Terrier .............................. 5Ask the Vet ................................ 7Humanitarian Named “Veterinarian of the Year”by Hartz..................................... 8

pets are given flea-control agents before alarge flea population can develop and thencontinually throughout the potential fleaseason is most likely to succeed. Insectgrowth regulators (IGRs) are particularlyeffective for this type of preventionstrategy.

M A R C H 2 0 0 5 V O L U M E 3 , N U M B E R 1

A NEWSLETTER OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE FOR VETERINARY PROFESSIONALSA NEWSLETTER OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE FOR VETERINARY PROFESSIONALS

(Figures 1 and 2). Eggs are laid on the host but quickly drop into theenvironment. Larvae hatch from eggswithin a few days and develop throughthree larval stages. The third larvalstage spins a silk-like cocoon anddevelops to a fully formed adult within.Adult fleas emerge from cocoons whenstimulated by host and environmentalfactors. The entire developmental cyclecan proceed in as little as 2 weeks inwarm, humid climates, whereas longerdevelopmental cycles are seen in cooler,drier climates.

It is important to remember thatapproximately 95% of the total fleapopulation (eggs, larvae, and pupae) residesin the pet’s environment (Figure 2E). Thiscan lead to continued pet infestations forseveral weeks after starting treatment. Forthis reason, a prevention strategy in which

(S)-Methoprene: ChemicalProperties and Applications for Effective Flea ControlByron L. BlagburnDistinguished University ProfessorDepartment of PathobiologyCollege of Veterinary MedicineAuburn University

2 HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • MARCH 2005 • VOL. 3, NO. 1

Consulting EditorsAlbert Ahn, DVM

Vice President of CorporateCommunications and VeterinaryOperationsThe Hartz Mountain Corporation

Bruce TrumanDivisional Vice President Animal Health and NutritionThe Hartz Mountain Corporation

HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM

is produced for The Hartz Mountain Corporation by Veterinary Learning Systems, 780 Township Line Rd.,Yardley, PA 19067.

Copyright © 2005 The Hartz Mountain Corporation. All rights reserved.

Hartz® and other marks are owned byThe Hartz Mountain Corporation.

Printed in U.S.A. No part of thispublication may be reproduced in anyform without the express writtenpermission of the publisher.

For more information on The HartzMountain Corporation, visitwww.hartz.com.

M A R C H 2 0 0 5 V O L U M E 3 , N U M B E R 1

A NEWSLETTER OF PRACTICAL MEDICINE FOR VETERINARY PROFESSIONALS

(S)-methoprene and other IGRs arebeing used with increasing frequencyfor flea control. Because of their safetyin both humans and animals and theirselectivity for insects, they are oftentermed biorational insecticides. IGRstarget developmental mechanismspresent in the eggs and larvae of insectssuch as fleas but not in pets and people.This unique feature can be exploited foreffective flea control because theimmature stages are not problematic forpets. Continued use of IGRs onanimals or in the environment willeffectively eliminate environmental eggs and larvae. This interrupts the flea life cycle and results in dramaticreductions in problematic adult fleapopulations. (S)-methoprene and otherIGRs are often combined withadulticides to achieve more rapid andeffective flea control.

(S)-methoprene and other IGRsfunction by mimicking the effects ofendogenous insect developmentalhormones (Figure 3). One of thesehormones, known as juvenile hormone( JH), is important in the regulation offlea development. JH functions tomaintain the embryonic or larval stage ofthe flea and thus prevents its maturationto pupa and adulthood. Developmentproceeds only after JH is enzymaticallydestroyed by esterases in the flea’scirculatory system. Decreasedconcentration of JH is the signal for the

flea to continue its development.(S)-methoprene and other IGRs mimicJH. Because of the similarity of JH and (S)-methoprene (Figure 4), the (S)-methoprene molecule cansuccessfully bind to the JH receptor inthe developing flea. This falsely signalsthe flea to remain in its present stage.Since (S)-methoprene differs slightly instructure from JH, it is resistant todegradation by endogenous enzymes.The inability of the flea to develop tosubsequent stages results in its death.

Research has shown that (S)-methoprene and other IGRs alsoaffect the development of embryos inflea eggs (embryogenesis) and thelarva’s ability to escape from the egg(eclosion or hatching) and may disruptfunction in a portion of the flea’sdigestive system. Other IGRs used tocontrol flea infestation includepyriproxyfen (Table 1) and fenoxycarb,which is not currently marketed in theUnited States.

Another class of flea-control agentscalled insect development inhibitors(IDIs) is also used to control egg andlarval flea stages. IDIs function byinterfering with the assembly of theflea’s chitinous external skeleton.Lufenuron is the only IDI currentlymarketed for flea control in the UnitedStates (Table 1).

(S)-methoprene, a terpenoidcompound, was the first of the IGRs to

gain regulatory approval in the UnitedStates and to be widely used. Efficacies of (S)-methoprene against immaturestages of C. felis are well documented.Studies include those targeting flea eggsand larvae in the laboratory and fleainfestations on animals and in theenvironment. Studies also include the use of (S)-methoprene alone and incombination with adulticidal fleacompounds. Applying (S)-methoprene to the hair of dogs and cats at rates of

Adult flea (first

generation)

Egg Larva Adult flea(second

generation)

Pupa

(S) - methoprene and other IGRs inhibit fleaembryonic development, egg hatch,

and/or larval molt

Figure 1— The flea life cycle.

HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • MARCH 2005 • VOL. 3, NO. 1 3

A2 to 10 mg/kg inhibited subsequentdevelopment of C. felis eggs to adult fleas.In vitro studies of (S)-methopreneincorporated into flea-rearing media atconcentrations of 0.01 to 0.03 ppm(0.001–0.003 mg/g of media) prohibited99% of 3.5-day-old flea larvae fromdeveloping to adult fleas. These samestudies also demonstrated that (S)-methoprene interfered with flealarvae’s ability to successfully spin acocoon. (S)-methoprene is marketed innumerous formulations designed forapplication on dogs and cats (Table 2).

Because of their unique mechanismof action, (S)-methoprene and otherIGRs are among the safest insecticidesknown. An oral dose of up to 34,600mg/kg in rats did not result in adversereactions. In dogs, the amount necessaryto cause serious toxicity and death isbetween 5,000 and 10,000 mg/kg, a dose that would be impossible to achieve using currently availableproducts. Similar safety profiles for (S)-methoprene were reported in swine,sheep, cattle, rabbits, hamsters, andguinea pigs. Safety studies also indicatedthat pure (S)-methoprene was notirritating when applied to the skin oreyes. However, it is important toremember that topical formulations of(S)-methoprene and other flea-controlagents may contain other componentscapable of causing dermal irritation orsensitivity.

Because topically applied (S)-methoprene may be ingested throughgrooming by dogs and cats, it isnecessary to explain the fate of orallyingested (S)-methoprene in animals.Radiolabeled (S)-methopreneadministered orally to cows appeared to

be metabolized to simple acetates thatwere subsequently incorporated into fatty acids, lactose, and cholesterol.(S)-methoprene metabolites did notaccumulate in tissue. Unmetabolized (S)-methoprene was excreted in feces(80%) and urine (20%).

Another indication of the safety of(S)-methoprene is its approval by theWorld Health Organization (WHO) forincorporation into drinking water formosquito control. WHO contends that(S)-methoprene poses no risk to humans,animals, or the environment. Since (S)-methoprene is metabolized ordegraded to simple products in theanimal’s body and the environment, it isunlikely to accumulate in plant andanimal food products.

(S)-methoprene provides severaldistinct advantages when combined withflea adulticides:

• (S)-methoprene kills eggs produced byadult fleas that survive betweenapplications of adulticidal agents.

• (S)-methoprene exerts its effects insuch small concentrations, its residualactivity exceeds that of topicaladulticides. When pet owners stopusing flea products because they nolonger see any fleas, (S)-methoprene incombination products provides someresidual protection against eggs.

• (S)-methoprene’s mechanism of actiondiffers from that of adulticides, so it isunlikely that fleas could becomeresistant to the effects of both agentsin combination products.

In summary, because of their potentactivity, unique mode of action, and

B

C

D

E

Figure 2—(A) Flea eggs (Ctenocephalides felis). (B) Flea larva (C. felis). Thelife cycle of fleas includes three larval stages. (C) Flea pupae (C. felis). This stage,also known as a cocoon, contains preemerged adult fleas. (D) Adult female flea(C. felis). Note the comb-like structures below the eyes and behind the head. (E) Eggs, larvae, and pupae of C. felis at the base of an indoor carpet. Ninety-five percent of the flea life stages live off the host.

(text continues on page 5)

Juvenile Hormone (JH)

Inhibition ofInhibition ofdevelopmentdevelopmentEgg or larvaEgg or larva

JHreceptor

Egg or larvaEgg or larva Egg/larvalEgg/larvaldevelopmentdevelopment

JHreceptor

Juvenile Hormone (JH) (S)-methoprene

Mechanism of action of (S)-methoprene and other IGRs

Enzymesremove JH

Enzymescannot remove(S)-methoprene

Fleas not exposed to ( S)- methoprene Fleas exposed to (S) -methoprene

Figure 3— Mechanism of action of (S)-methoprene and other IGRs.

4 HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • MARCH 2005 • VOL. 3, NO. 1

TABLE 1: Insect Growth Regulators (IGRs) and Insect Development Inhibitors (IDIs) Effective Against Fleas onCompanion Animals

IGR or IDI Product Names Formulation(s) Target Stage

Lufenuron (IDI) Program, Sentinel (NovartisAnimal Health)

Flavored tablet, oral suspension,injectable suspension

Eggs

Pyriproxyfen (IGR) Many, including Bio Spot andScratchex (Farnam Companies),KnockOUT (Virbac), EctoKyl(DVM Pharmaceuticals), andPreTect (Sergeant’s Pet CareProducts)

Spot-on, spray, shampoo, collar Adultsa, eggs, larvae

(S)-Methoprene (IGR) Many (see Table 2) Spot-on, spray, shampoo, collar Adultsa, eggs, larvae

aProducts effective against adult fleas also contain adulticides.

TABLE 2: Examples of Flea Control Products that Contain (S)-Methoprene

Product Name (Manufacturer) Host Species Formulation Ingredients Target Parasites

Frontline Plus (Merial) Dogs, cats Topical spottreatment

Fipronil, (S)-methoprene Fleas (adults, eggs, larvae)

Ticks (all stages)

Hartz® ADVANCED CARE®

4 in 1 Plus+ (The HartzMountain Corporation

Dogs, cats Topical spottreatment

Phenothrin, (S)-methoprene Fleas (adults, eggs, larvae)

Ticks (adults)Mosquitoes (adults)

Sergeant’s Double Duty Flea& Tick Collar (Sergeant’s PetCare Products)

Dogs, cats Collar Propoxur, (S)-methoprene Fleas (adults, eggs, larvae)

Ticks (all stages)

Vet-Kem Ovitrol Plus Flea &Tick Shampoo (WellmarkInternational)

Dogs, cats Shampoo Pyrethrin, piperonyl butoxide,(S)-methoprene

Fleas (adults, eggs, larvae)

Ticks (all stages)

HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • MARCH 2005 • VOL. 3, NO. 1 5

enhanced activity against fleadevelopmental stages when combinedwith adulticidal agents, (S)-methopreneand other IGRs or IDIs can contributesignificantly to the successful control offleas and flea-induced diseases. A flea-control strategy that combines adulticideswith IGRs and/or IDIs will likely achieveboth faster and longer-lasting fleacontrol.

SUGGESTED READINGBlagburn BL, Clekis T, Dryden MW, et al: Integrated

flea control: Effective strategies to minimizeresistance. Lenexa, KS, Veterinary HealthcareCommunications, 2002.

Blagburn BL: Advances in ectoparasite control: Insectgrowth regulators and insect development inhibitors.Vet Med 91:9–14, 1996.

El-Gazzar LM, Koehler PG, Patterson RS, Milo J:Insect growth regulators: Mode of action on the catflea, Ctenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J Med Entomol 25:651–654, 1986.

Garg RC, Donahue WA: Pharmacologic profile ofmethoprene, an insect growth regulator, in cattle,dogs, and cats. JAVMA 194:410–412, 1989.

Olson A: Ovicidal effects of the cat flea, Ctenocephalidesfelis (Bouch), of treating fur of cats and dogs withmethoprene. Int Pest Control 27:10–16, 1985.

Palma KG, Meola SM, Meola RW: Mode of action ofpyriproxyfen and methoprene on eggs ofCtenocephalides felis (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae). J MedEntomol 30:421–426, 1993.

Rust MK, Dryden MD: The biology, ecology, andmanagement of the cat flea. Annu Rev Entomol42:451–473, 1997.

Siddall JB: Insect growth regulators and insect control: A critical appraisal. Environ Health Perspect14:119–126, 1976.

A O

O OCH3H

B

O

O O

Figure 4— Note the similarchemical structures of juvenile hor-mone III (A) and (S)-methoprene (B).

The Go-To Glen

(text continued from page 3)The American Kennel Club Welcomesthe Glen of Imaal Terrier

The American Kennel Club welcomes the multifunctional, even-tempered, and powerfully built Glen of Imaal Terrier, who joins his cousins, the Kerry

Blue, Soft Coated Wheaten, and Irish terriers, in the registry.

A TOUGH TERRAIN, AN EVEN TOUGHER TERRIER The Glen of Imaal Terrier is indigenous to the wild and barren place from which

he takes his name. The region’s farmers, descendents of Flemish and Hessian soldiers,developed the breed in the 17th and 18th centuries in this area located on Ireland’seastern seaboard. Surviving in this bitter locale required every resource available to thefarmer, and a dog who could not make himself useful would not last long.

Though the smallest of the four Irish terrier breeds, the Glen is exceptionallyheavy-boned and sturdy. Long and low to the ground, with powerful head and legsbowed, the breed guarded stock, hunted badger, fox, and otter, and dispatched verminof all sorts around the farmstead. The Glen was purposely developed closer to theground and stockier than other terriers. This made them optimal badger dogs—theirpunishing jaws and short-legged bodies enabled them to spar with their stronger,fiercer quarries. When digging, the bowed front legs and turned-out feet were ideal forthrowing dirt to the sides rather than back in the hole.

HAIRY AND HEALTHYThe Glen is meant to be shown with a natural coat. This double-coated breed with

a silky undercoat mixed with a wiry outercoat does not require the scissoring skillneeded for Kerries and Soft Coated Wheatens, nor is frequent stripping required. Thisdoes not mean that the Glen—a harsh-coated breed—has no grooming needs.Brushing regularly and stripping once or twice annually will prevent almost allshedding. Clippers, however, are not an option.

Most experts agree that the Glen is blessedly free of hereditary defects, though anybreed can carry recessive genes for a range of universal defects. Rare cases of thecommon genetic disorder progressive retinal atrophy have been reported. Hip dysplasiais found in most breeds, including Glens. Like all terriers, the Glen can be afflictedwith skin irritations, usually as a result of flea allergies, although there are fewerproblems than previously thanks to selective breeding.

A STUDY IN CONTRASTSOne of the charms of this “Irish Gladiator” is that he is a bit of a paradox. Even

though the Glen is known for his intensity, he is a placid, agreeable family dog whosefans claim is less excitable than some of the other members of his group.

While the Glen can be stubborn with game, he takes easily to obedience training;he is gentle with children yet will not shy away from defending himself. He is small instature, but his guttural bark and stocky body give him an appearance of might,making him an excellent little watchdog. He responds well to praise and is sensitive toscolding. Fans of the Glen warn, however, that his complex character means he is notthe perfect fit for every household.

Committed fanciers have maintained the Glen’s status as a substantial and diligentworker and a pleasing and affectionate companion. Unless, of course, you are a badger.

Albert Ahn, DVM, is Vice President of Corporate Communicationsand Veterinary Operations at The Hartz Mountain Corporation.

ASK THE VET

HARTZ® COMPANION ANIMALSM • MARCH 2005 • VOL. 3, NO. 1 7

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!• Have questions or comments? Call our Consumer Relations Department at 800-275-1414 and ask to speak to a Hartz staff

veterinarian or email us at [email protected].

• To obtain a Hartz Veterinary Catalog of products, please call 800-999-3000 x5118 or email us at [email protected].

QA

Is the ongoing use of the insect growthregulator methoprene sufficient to control fleas in a single-pet home?

Methoprene is a synthetic insect growth regulator orjuvenile hormone mimetic and is further classified asa terpenoid. Juvenile hormones maintain the larvalstage in the insect or prevent metamorphosis; whenthe level of juvenile hormone drops, pupal and adultdevelopmental stages begin. Methoprene is ovicidalwhen female fleas are exposed on the pet andlarvicidal in the environment.

Insect growth regulators are critical components inintegrated pest management for total control of fleas.They do not have a direct kill effect on adult fleas butwill help decrease the flea population by blocking fleaegg production. However, in the case of a currentflea infestation, it is best to use an insect growthregulator in combination with insecticidal treatmentsto help kill adult fleas.

Articles found in the Hartz Companion AnimalSM newsletter can be copied and distributed to your colleagues, staff, and clients.

Additional newsletters may also be obtained by contacting us at [email protected] or by phone at 800-275-1414.

QA

What natural ways can pet owners helpcontrol fleas in the environment?

The nematode Steinernema carpocapse parasitizesfleas and is sometimes used for flea control. Thenematodes enter the flea larvae and then excrete abacterial compound that breaks down the larvae’sinternal organs. Unfortunately, the nematodes cannotestablish themselves well in the environment, andthey have to be applied repeatedly (every month) toprovide effective flea control.

Other ways to help control fleas include:

• Frequent vacuuming of the pet’s environment.After vacuuming, the bag should be placed in aplastic bag and placed in an outdoor trashreceptacle. This prevents emergence of new fleasfrom the immature stages in the vacuum bag.

• Grass should be kept short by mowing frequently.Immature flea stages can be destroyed by directsunlight; so keeping the lawn short helps decreasethe number of emerging fleas.

Veterinary Learning Systems780 Township Line RoadYardley, PA 19067

PRESORTED STANDARDU.S. POSTAGE

PAIDBENSALEM, PAPERMIT #118

401227

Humanitarian Named“Veterinarian of the Year”by Hartz

Dr. Earl O. Strimple, a leader in the movement to elevatethe human condition through soothing interactions withanimals, has been named Veterinarian of the Year for 2005by The Hartz Mountain Corporation.

Over the past 25 years, Dr. Strimple has spearheaded arange of programs bringing dogs, cats, rabbits, and othercompanion animals into direct contact with hospital patients,nursing home residents, prison populations, disadvantagedchildren, hospice patients, and more. The program that heheads in Washington, DC, presently makes regular visits toWalter Reed Army Hospital in Bethesda, MD, where trainedvolunteers and their pets spend time with severely woundedsoldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Dr. Strimple’s compassionate volunteers have quietlyenriched the lives of thousands of adults and children,” saidDr. Albert Ahn, Vice President of Corporate Communicationsand Veterinary Operations at Hartz. “We salute Dr. Strimple’stireless efforts to promote the human–animal bond throughcommunity outreach, and we are proud to give this award tosuch an outstanding individual.”

Dr. Strimple, who practiced veterinary medicine for over 30years and founded the not-for-profit organization PAL(People Animals Love), will receive the grand prize of $5,000.

He was nominated for the award by Ms. Margery Yeager,whose family pets were treated by Dr. Strimple for over 20years. She has also been a PAL volunteer. “Through thisprogram, many lives are touched with the healing presence ofanimals,” she said. “Dr. Strimple does all of this work withdedication and humility. He deeply deserves to be rewarded forhis excellent practice as a veterinarian and his substantialcontributions to often overlooked populations in thecommunity.”

The runners up for 2005 were Dr. Lee Morgan of theGeorgetown Animal Hospital in Washington, DC, and Dr.Lori Civello of the Glendale Animal Hospital in GlendaleHeights, Illinois. Dr. Morgan trains service dogs for the SeeingEye Foundation and The Guide Dogs for the Blind, and hishospital provides support for a variety of rescue foundationsand animal shelters. Dr. Civello runs an adoption programthrough her hospital. She also works with many shelters andrescue groups to provide discounted care, spays, and neuters toanimals awaiting new homes. Drs. Civello and Morgan eachreceived a $2,500 award.

Dr. Earl O. Strimple, left, receives the 2005 Veterinarian of theYear award from Dr. Albert Ahn, Vice President of Corporate Communications and Veterinary Operations at Hartz.