Hansen Ljubljana

-

Upload

ivan-visnjic -

Category

Documents

-

view

28 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Hansen Ljubljana

1

Documenta Praehistorica XXXVIII (2011)

Figurines in Pietrele>Copper age ideology

Svend HansenThe German Archaeological Institute (DAI), Eurasia Department, Berlin, DE

Introduction

Figurines are among the characteristic features ofthe South-East European, Anatolian and Near East-ern Neolithic and Copper Age, and have been attra-cting attention since the 19th century. They belongto the most thoroughly published class of objects,but the quality of illustrations remains a major pro-blem in discussing their details. Elisabeth Ruttkaywas one of the few researchers who had dealt withthis problem, and in several articles explained howto recognise the details of figurines (Ruttkay 1972;1992; 2001; 2005). In one of her outstanding stud-ies, she showed the inter-regional connections of acertain symbol in the South East European Neolithicand Copper Age which she had found on a spoon(Ruttkay 1999). Figurines were used in settlementsof local communities, and modelled according to aregional style (of different ’cultures’), but their ge-neral features were rooted in a long tradition andwere supra-regional (Hansen 2007).

During the tenth millennium BC, a major shift in fi-gurine production took place. The whole posture ofthe figurines’ bodies changed (Fig. 1). The upperpart of their body is now slightly leaned back; thehead is laid a little in the neck; their gaze is turnedtoward the sky. In comparison to Palaeolithic statu-

ettes, which cannot stand on their bent-in legs andhold their head bowed down, Neolithic figurinesconstitute something basically new. In the Early Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, new types of representa-tion and formal means of expression were invented;now we find both standing and seated figurines.There is an evident break between Palaeolithic andNeolithic sculpture.

Figurines belong to the Neolithic package whichcame to the Balkans via Anatolia. They seem to beclosely connected with painted pottery. There is asharp division between the Balkans and WesternEurope, where figurines are completely absent fromcontexts of impresso or cardial ceramics.

After an Early Neolithic horizon of the late seventhand early sixth millennium with similar figurinesfrom Turkish Thrace to the Middle Tisza region, al-ready in the second half of the sixth millennium weobserve regional variations in figurine style and qua-lity, in the number of different types and in thenumber of figurines found in settlements. In thefifth millennium, these variations between differentregions became more and more obvious. In Thessaly,the style of the figurines changed profoundly and

ABSTRACT – Major trends in figurine production of the copper age settlement of Pietrele (Romania)are discussed. The bone figurines are seen as an ideological innovation of the Early Copper Agesystem in the eastern Balkans.

IZVLE∞EK –

KEY WORDS – Copper Age; Romania; Pietrele; figurines; ideology

Svend Hansen

2

their numbers decreased. In the Central Balkans,figurine production ended with the Vin≠a culture,around 4650 calBC according to the new radiocar-bon dates (Bori≤ 2009). The same is true for theTisza culture in Eastern Hungary.

In most regions, figurine production came to an endin the middle of the fifth millennium. The apparen-tly sudden end of the figurines was interpreted asthe result of profound changes in spiritual life, andwas seen in connection with migrations (Gimbutas1994). But a closer look at the material shows thatthe causes were more complex. In this respect, it isworth looking back from the West to the Near East.It is surprising that also in the Near East, figurineproduction ceased in the fifth millennium. One ofthe latest examples comes from the Ubaid culture.In the cemeteries of Eridu and Ur, mostly female fi-gurines, but also some male figurines were found(Parrot 1981.96, Figs. 92, 93, 98). The rhythm of fi-gurine production in the Near East and South-EastEurope seems to have been similar.

In contrast to the decline of figurine production inthese regions, figurines became very popular in theEastern Balkans. In the middle of the fifth millen-nium, when the KGK VI complex emerged betweenthe Aegean and the Danube, figurine production wasintensified and the number of types increased. It isnoteworthy that some types were still in the tradi-tion of Neolithic figurine production, like the largesitting figurine from Pazard∫ik (Fig. 2), but new typesalso appeared. One of the most remarkable changesis the introduction of bone figurines. Since the tenthmillennium, anthropomorphic figurines had neverbeen made of bone. Because the material and mea-ning of the figurines were closely related, the intro-duction of a new material can not only be seen asan innovation, but also as an ideological change.The same is true for the first metal figurines.

Pietrele at the Lower Danube

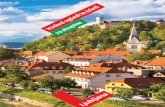

Before discussing some aspects of the figurines fromPietrele and their social significance, it is necessaryto give a short general introduction to the Pietreleexcavation. The Eurasia Department of the DAI, theRomanian Institute of Archaeology, and FrankfurtUniversity, have been excavating in Pietrele since2004 (Hansen et al. 2010 with bibliography of ear-lier reports). The ‘Magura Gorgana’ settlement moundis slightly oval, with a diameter of 97m in the east-western direction and 90m in the north-southern di-rection (Figs. 3–4). The tell is 9m high and the cul-

tural layer is probably of the same depth. The Cop-per Age settlement ends around 4250 BC. We havereached layers which could be dated to around 4500calBC. After the Copper Age, the mound has neverbeen settled again (Berciu 1956).

Pietrele is situated on the left bank of the Danube,around 170km from the Black Sea coast. It was partof a system of settlement mounds along the lowerDanube and in North Eastern Bulgaria, most of whichwere probably erected at the same time before 4600BC. It is worth noting that these mounds were thefirst settlements of this type in these regions: thelatest tell settlements in South-East Europe.

Pietrele is part of the so-called Gumelnita culture,which is considered part of the Kod∫adermen-Gu-melnita-Karanovo VI (KGK VI) complex. Karanovoin Bulgarian Thrace is still the fixed point of East-ern Balkan chronology, even if its stratigraphy forthe KGK VI period is quite low (less than 4 metres)compared to the Pietrele sequence with 7m and fourhouses.

The background of our excavation is the enigma ofVarna (Fol and Lichardus 1988). The idea was toexcavate at Pietrele to contribute to a better under-

Fig. 1. Paleolithic and Neolithic body orientationof figurines (after Hansen 2007).

Figurines in Pietrele> Copper age ideology

3

standing of the increasing social inequality whichis displayed in the graves in Varna. How was it pos-sible that some persons, like the man in grave 43,were buried with an abundance of prestigious itemslike spondylus, gold, and copper? The question is im-portant, since Varna is not a single case, but part ofa widespread tendency (Demoule 2007). In South-East Europe this social inequality was a part and theresult of a new system. Several elements characteri-sed this system. First, the new copper weapons werethe starting-point for the relatively rapid develop-ment of weapon technology in the next 700 years.The need for weapons was the engine of coppermining. A second major point was the new represen-tation of power, not only in graves, but also in tellsettlements. Tells were built to draw distinctions be-tween people. Before 2008, no radiocarbon datesfrom Varna cemetery were available. By stylisticcomparisons, Varna was dated to the end of the KGKVI sequence. With new radiocarbon evidence it be-came clear that the rich graves in the cemetery hadto be dated between 4560 and 4450 calBC (Highamet al. 2007). Varna stands at the beginning of KGKVI development, not at the end. Our excavation inPietrele does not tell the story of development upto Varna, but from Varna on.

One of the results of the geophysics in the 2004campaign in Pietrele was a plan of the settlement atthe mound, which consisted of four rows of houses(Fig. 5). The second result was evidence of a muchlarger settlement around the mound. Since then, acompletely new dimension of Copper Age settlementhas required (Lazarovici and Lazarovici 2007). Itdiffers from the small settlements which were recon-structed after the excavations in Bulgaria and Roma-nia, and accords with similar large scale Late Neoli-thic settlements in Bosnia (Hofmann et al. 2007)and Hungary (Raczky and Anders 2006). We haveto excavate larger areas to discover if the settlementaround the tell is earlier or contemporaneous. But itseems clear that living on the settlement mound dif-fered from living around the tell, which could ex-plain the wealth of finds on the settlement mound.

One surprising point was the high quantity of morethan 60% of wild animals in the settlement. Therewere large-scale hunting and fishing activities. Thedistribution of artefacts enables the identification ofspecialised households. The occupants of the housesin trench F were mainly engaged in fishing and hun-ting. Almost all our hunting weapons/tools camefrom these houses. Two unburnt looms and severalloom weights from the burnt houses show that wea-

ving was one of the main activities of the occupantsof the houses in trench B. The specialised crafts-manship of the Early Copper Age is visible in seve-ral products in the settlement mound, such as thecopper artefacts. The specialists did not necessarilywork in this settlement. Specialised and experien-ced craft workers were also needed to produce longblades of up to 30cm.

In the flat settlement around the mound, we ope-ned several trenches in the last two campaigns, withsurprising results. In trench J, the Copper Age lay-ers came to light at a depth of 170cm (Fig. 6). Thepreservation was not so bad. We found an oven andan installation for grinding. In the western part, anumber of large sherds came to light which origi-nally belonged to a pot standing on a clay bench nextto the oven. Beneath one house, we were able tounearth a second, older house. This is the first timethat such a sequence has been observed in a flat set-tlement.

Related to pottery processing, a large pithos with aheight of 130cm and a capacity of 400 litres couldbe restored (Fig. 7). It is quite clear that the makingof this pithos required specialised craftsmanship aswell. The distinction between potters producing ’nor-mal’ pottery and potters making large pots has beenshown by ethnographic studies. Such large vesselsare not unknown from other Neolithic sites: a remar-kable piece was found at Toptepe in Turkish Thrace(Fig. 8). But pithoi larger than one metre seem tohave been produced only in certain Neolithic Cul-tures.

Pietrele was a central place in a much larger econo-mic and political system with a clear division of la-bour and social differentiation on the Lower Da-nube and in Northern Bulgaria.

Figurines in Pietrele

The use and working of metal since the Pre-potteryNeolithic has been established for Eastern Anatolia,but metal was not in the Neolithic Package in whichmost of the innovative techniques came to Europe atthe end of the 7th millennium and beginning of the6th millennium. All in all, it was around 1000 yearsbefore people began to look for metals, to collectsurface material, began mining and process the cop-per. In the first half of the 5th millennium, coppercasting was established in the Central Balkans. Inthe middle of the 5th millennium copper and goldwere used in large parts of South Eastern Europe. It

Svend Hansen

4

must have been a fascinating time. A new materialappeared; its qualities were different from most ofwhat was known at that time. It was hard and soft;it was not easy to break it; it had special colours andwas shiny. But the most important quality was thatit was never destroyed. The dynamic and special at-tractiveness of metal lay in the fact that it could bemelted. Every broken axe could be melted downand a new axe recast. Alternatively, a broken axecould be melted down in order to cast an object indemand, such as a bracelet or a chisel. Thus, two re-markable features were united in metal that wereabsent from other materials: reparability (that is, re-newal) and convertibility.

With the possibility of re-melting an object and pro-ducing a new object, a new quality appeared: na-mely, the material remained (almost) whole; it wasnot used up. Once exploited in the mine and proces-sed, metal could be used repeatedly to produce newobjects. Thus unlike broken stone axes, it was sensi-ble to accumulate metal for use when needed. Allmetal objects could, and usually were, reused. Tosummarise, the enormous technical and social pos-sibilities offered by metal were a challenge to exist-ing ways of thinking.

We will first discuss the first human representationin metal. In 2009, we found a gold pendant togetherwith a large number of spondylus beads in one ofthe burnt houses on the mound (Fig. 9). Such goldenamulets are often interpreted as human figurines.Three main distribution areas are known: Greece,where they were mostly found in caves; the EasternBalkans, where they were predominantly found insettlement mounds (Chohadziev 2009) and in thecemetery of Varna; and in the Carpathian basin,where they were used as grave goods. In some ca-ses, they were included in votive depositions. Thecase of the golden amulet also sheds some light onthe practice of deposition. Its weight is half of theamount of the gold found in the richest grave inVarna. This shows that the accumulation of wealthwas possible in different regions in South East Eu-rope at the same time. The use of gold for amuletsor animal figurines, or even representations of cer-tain bones, was supposed to transfer the qualities ofthe material to the representation.

Bone figurines are very common in KGK VI groupsettlements. They are quite numerous, and do notvary much in quality. Some still have their originalcopper ornaments. In Pietrele, we were able to showfor the first time that clay beads were also used as

ornaments. As already mentioned, bone figurinesdid not appear before the Copper Age. In the EarlyCopper Age, flat bone figurines were very commonand widespread, and produced in large numbers.The close connection between human figurines andclay was not accidental – it was supposed to expresssome common qualities of human beings and clay asa material on a metaphorical level. Using animalbone to represent human beings must have openeda new horizon of thought. Animal bone was used forrepresentations of women and men (Fig. 11).

The male figurines are clearly phallic. This is theonly type of figurine which occurs in settlements aswell as in graves. Figurines were normally not usedas grave goods. Therefore, it is the only figurinegroup in the European Neolithic which allows a com-parison between settlement and grave. In Varna,these phallic representations are known in the wel-lequipped graves, such as grave 36. An outstandingexample of the male representations is a marble fi-gurine (Fig. 10) from Grave 3 – one of the so-calledmask graves in the centre of the graveyard – whichwas decorated with several golden tutuli. It is theonly example of a copy of a bone figurine in marble.

Bone figurines are known from 20 graves in Varna,14 kenotaphs and 6 burials. All of these were com-bined with metal and/or spondylus. All graves con-taining figurines belong to the small high statusgroup. On the other hand, in grave 43, the richestone, no phallic figurine was found.

In Pietrele, we found six figurines on the settlementmound. A further three figurines have come fromexcavations of Dumitru Bercius in the 1940’s. All fi-gurines were found in houses; not a single one camefrom open areas street and courtyards.

In comparison with other settlement mounds, thenumber of figurines is relatively high in Pietrele(Fig. 12). Eight figurines were found in Ruse, andnine in Karanovo. In Goljamo Del≠evo, four figuri-nes were found. We have to consider that in all theseplaces, a much larger part of the settlement moundwas excavated than in Pietrele. In general, the highnumber of such figurines is an argument for the so-cial significance of the settlement and the high sta-tus of its inhabitants. An interesting detail is the com-plete absence of these figurines in the Kod∫adermentells in North Eastern Bulgaria.

The bone figurines are representations of male ge-nitals. As Hans-Peter Duerr has argued by using eth-

Figurines in Pietrele> Copper age ideology

5

nographical and historical evidence, the demonstra-tion of the penis is an aggressive demonstration ofmale power. In the case of Gumelnita, it is under-lined by their size. The social exclusivity which canbe seen in the Varna graves shows that male domi-nance was expanding in the Early Copper Age at thesame time as social differentiation was increasing.

In the Pietrele settlement mound the number ofclay anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines isquite high. 391 anthropomorphic and 66 zoomor-phic figurines were found on the mound where weexcavated approximately 940m3. In the flat settle-ment, their number is much smaller, but it is tooearly for a precise comparison. The quality of the fi-gurines is different, which is obvious in the model-ling of the heads. There are very simple forms ofheads, heads with holes in which copper ornamentswere fixed, and figurines with plastic modelling (Figs.13–14).

The Gumelnita figurines rely on the Late Neolithicfigurine types of the Tisza and Lengyel cultures muchmore than on the older tradition of Hamangia in theEast, or the Boian in Southern Romania. One groupconsisted of standing figurines with outstretchedarms, a position found among figurines in the sec-ond half of the 5th millennium in wider parts of Eu-rope, as can be seen in the figurine from Zauschwitzin Saxony from Stroke Linear Pottery culture, a Len-gyel site at Falkenstein-Schanzboden, and a KGK VIsite at Krivodol (Figs. 15–17).

Human representations are widespread, and thegreat distance between Krivodol in Bulgaria andZauschwitz in Saxony can be underlined by anothercase. In 2008, we found a pot with a flat bottom andvertical rim. The incised decoration is not very com-mon in Pietrele. On the bottom, a human being isincised with raised arms and spread legs (Fig. 18).Similar pictures are known from several Stroke pot-tery pots in Saxony and Bohemia (Fig. 19), wherethey were interpreted as people at prayer. But Iwould prefer an interpretation which takes into con-sideration the sexual dimension of these pictures.

The striking characteristics of all these clay figurinesare the variety of types and their large number. Ad-ditionally, many other clay models exist, especiallyminiature furniture and small clay houses. Severalhouse models came to light during the excavationcampaigns in Pietrele. Lids with handles in the formof houses were also quite popular (Reingruber2008). Jan Trenner (2010) could show that the oc-

currence of house models has a chronological andregional focus. They are very common in the ‘Kod∫a-dermen-Gumelnita-Karanovo VI-complex’, an earlierdistribution centre is Thessaly and Macedonia. Thelarge number of house models in Pietrele is not sur-prising compared to other settlements in the EasternBalkans.

A large clay house was found in the Gumelnita set-tlement of Malul Rosu near Sultana, com. Mânasti-rea, jud. Calarasi (Halcescu 1995). In the walls andthe roof, seventeen holes with diameters of 4.5–5.0cm can be found (Hansen 2007.Taf. 438). Themodel house is 32cm long, 27.5cm wide, and 21cmhigh. Under the broken house, the excavators found11 gold objects which were probably originally ‘sto-red’ in the clay house (Fig. 20).

Several fragments of a very large house (Fig. 21)were found in 2010 under the living level of thehouse where the gold pendant (Fig. 9) was found in2009. The preserved length is 55cm and the heightis 20cm. The walls are decorated with a chess pat-tern of reddish and whitish fields. Such decorationsare known from the much older houses in Thessaly(Krannon, Larisa), as well as in Walachia (Jilava: cf.Trenner 2010).

The similarity of the pattern of younger and oldermodels in two different areas should be interpretedas an expression of a common symbolic language inthe South East European Neolithic and Copper Age,as has been shown in the masterly article by Elisa-beth Ruttkay (1999) already cited.

Svend Hansen

6

BERCIU D. 1956. Sapaturile de la Pietrele, Raionul Giur-giu 1943 si 1948. Materiale si Cercetari Arheologice 2:503–544.

BORI≥ D. 2009. Absolute Dating of Metallurgical Innova-tions in the Vin≠a Culture of the Balkans. In T. L. Kienlinand B. Roberts (eds.), Metals and society. Studies in ho-nour of Barbara S. Ottaway. Universitätsforschungen zurprähistorischen Archäologie. Habelt, Bonn 2009: 191–245.

CHOHADZIEV A. 2009. The Hotnitsa Tell – 50 years later.Eight years of new excavations – some results and perspe-ctives. In F. Drasovean, D. L. Ciobotaru, M. Maddison(eds.), Ten years after: The Neolithic of the Balkans, asUncovered by the Last Decade of Research. Proceedingsof the Conference held at the Museum of Banat on Novem-ber 9th–10th 2007. Timisoara: 67–79.

COBLENZ W. 1965. Eine Venus von Zauschwitz, Kr. Bor-na. Ausgrabungen und Funde 10: 67–69.

DEMOULE J.-P. (ed.) 2007. La révolution néolithique enFrance. La Découverte. Paris.

FOL A., LICHARDUS J. (eds.) 1988. Macht, Herrschaft undGold. Das Gräberfeld von Varna (Bulgarien) und dieAnfänge einer neuen europäischen Zivilisation. StiftungSaarländischer Kulturbesitz. Saarbrücken.

GIMBUTAS M. 1994. Das Ende Alteuropas. Der Einfallder Steppennomaden aus Südrußland und die Indoger-manisierung Mitteleuropas. Archaeolingua Alapítvány.Budapest.

HALCESCU C. 1995. Tezaurul de la Sultana. Cultura si civi-lizatie la Dunarea de Jos 13–14: 11–18.

HANSEN S. 2007. Bilder vom Menschen der Steinzeit.Untersuchungen zur anthropomorphen Plastik derJungsteinzeit und Kupferzeit in Südosteuropa. Archäo-logie in Eurasien 21. Mainz.

HANSEN S., TODERAS M., REINGRUBER A., GATSOV I.,KAY M., NEDELCHEVA P., NOWACKI D., RÖPKE A., WAHLJ., WUNDERLICH J. 2010. Pietrele, "Magura Gorgana“. Be-richt über die Ausgrabungen und geomorphologischenUntersuchungen im Sommer 2009. Eurasia Antiqua 16:43–96.

HIGHAM T. 2007. New perspectives on the Varna ceme-tery (Bulgaria) – AMS dates and social implications. An-tiquity 81: 640–654.

HOFMANN R., KUJUNDΩI∞-VEJZAGI≥ Z., MÜLLER J., MÜL-LER-SCHEEßEL N., RASSMANN K. 2007. Prospektionen

und Ausgrabungen in Okoli∏te (Bosnien-Herzegowina):Siedlungsarchäologische Studien zum zentralbosnischenSpätneolithikum (5200–4500 v. Chr.). Bericht der Rö-misch-Germanischen Kommission 8: 41–212.

KENT S. (ed.) 1990. Domestic architecture and the useof space. An interdisciplinary cross-cultural study. NewDirections in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press,Cambridge 1990.

LAZAROVICI C. M., LAZAROVICI G. 2007. Arhitecturaneoliticului si epocii cuprului din România II. Epocacuprului. Trinitas. Iasi.

NEUGEBAUER-MARESCH C. 1995. Mittelneolithikum: DieBemaltkeramik. In E. Lenneis, C. Neugebauer-Maresch, E.Ruttkay (eds.), Jungsteinzeit im Osten Österreichs. Nie-deröst. Presse, St. Pölten-Wien: 57–107.

ÖZDOGAN M., DEDE Y. 1998. An anthropomorphic vesselfrom Topetepe, eastern Thrace. In M. Stefanovich, H. To-dorova, H. Hauptmann (eds.), James Harvey Gaul in Me-moriam. In the Steps of James Harvey Gaul. Volume 1,Sofia: 143–152.

PARROT A. 1981. Sumer. Gallimard. Paris.

RACZKY P., ANDERS A. 2006. Social Dimensions of theLate Neolithic Settlement of Polgár- Csőszhalom (EasternHungary). Acta Archaeologica Academiae ScientiarumHungaricae 57: 17–33.

REINGRUBER A. 2008. Deckel mit besonderen Griffen ausPietrele, Rumänien. In F. Falkenstein, S. Schade-Lindig, A.Zeeb-Lanz (eds.), Kumpf, Kalotte, Pfeilschaftglätter. ZweiLeben für die Archäologie. Gedenkschrift für Annema-rie Häusser und Helmut Spatz. Studia honoria 27. Ver-lag Marie Leidorf, Rahden: 217–226.

RUTTKAY E. 1973. Ein fragmentiertes Sitzidol der Leng-yel-Kultur aus Wetzleinsdorf, Niederösterreich. Mitteilun-gen der Anthropologischen Gesellschaft in Wien 103:27–39.

1992. Beiträge zur Idolplastik der Lengyel-Kultur. InA. Lippert and K. Spindler (eds.), Festschrift zum 50jährigem Bestehen des Institutes für Ur- und Frühge-schichte der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck.Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäolo-gie Band 8. In Kommission bei Dr. Rudolf HabeltGmbH, Bonn: 511–522.

1999. Ein Heilszeichen aus dem 5. Jahrtausend v. Chr.in der Lengyel-Kultur. Das Altertum 45: 271–291.

REFERENCES

Figurines in Pietrele> Copper age ideology

7

2001. Über anthropomorphe Gefäße der Lengyel-Kul-tur – Der Typ Svodín. Preistoria Alpina 37: 255–272.

2005. Innovation vom Balkan – Menschengestaltige Fi-guralplastik in Kreisgrabenanlagen. In F. Daim and W.Neubauer (eds.), Zeitreise Heldenberg. Geheimnisvol-le Kreisgräben. Katalog zu NiederösterreichischenLandesausstellung 2005. Katalog des Niederösterrei-chischen Landesmuseums NF 459. Verlag Berger Horn,Wien: 194–202.

RUTTKAY E., HARRER A. 1993. Ein neuer Sitzidoltyp derLengyel-Kultur aus Winden bei Melk, Niederösterreich.Fundberichte aus sterreich 32: 543–551.

SPATZ H. 2003. Hinkelstein: Eine Sekte als Initiator desMittelneolithikums? In J. Eckert, U. Eisenhauer, A. Zim-mermann (eds.), Archäologische Perspektiven. Analysenund Interpretationen im Wandel. Festschrift für JensLüning zum 65. Geburtstag. Studia honoraria. Interna-tionale Archäologie. Vol. 20. Verlag Marie Leidorf, Rah-den: 575–587.

TODOROVA H. 1982. Kupferzeitliche Siedlungen inNordostbulgarien. Verlag C. H. Beck. München 1982.

TRENNER J. 2010. Untersuchungen zu den sogenanntenHausmodellen des Neolithikums und Chalkolithikumsin Südosteuropa. Universitätsforschung zur prähistori-schen Archäologie. Band 180. Rudolf Habelt Verlag. Bonn.

Svend Hansen

8

Fig. 4. Magura Gorgana (Model: K.Scheele).

Fig. 3. Magura Gorgana near Pietrele (Pho-to: S. Hansen).

Fig. 2. Seated figurine from Pazard∫ik (af-ter Hansen 2007).

Figurines in Pietrele> Copper age ideology

9

Fig. 5. Reconstruction of the settle-ment plan (Plan: B. Song).

Fig. 6. Pietrele; trench J with remains of the ovenand grinding installation (Photo S. Hansen).

Fig. 7. Pithos from Pietrele 1.2m high (Photo S.Hansen).

10

Fig. 10. Marble figurine from Varna (af-ter Fol and Lichardus 1988).

Fig. 9. Gold pendant from Pietrele (Photo: M. Toderass).

Fig. 11. Bone figurines from Pietrele(Photo: S. Hansen).

Fig. 8. Anthropomorphic Pithos fromToptepe (after Özdogan and Dede 1998).

11

Fig. 12. Bone figurines in South-EastEurope. Large symbols: more than 7figurines (Map: S. Hansen).

Fig. 13. Pietrele. Standing Fi-gurines (Photo: S. Hansen).

Fig. 14. Pietrele. Figurineheads (Photo S. Hansen).

Svend Hansen

12

Fig. 16. Figurine from Falkenstein- Schanzboden(after Neugebauer-Maresch 1995).

Fig. 15. Figurine from Zauschwitz (afterCoblenz 1965).

Fig. 17. Figurine from Krivodol (Photo S.Hansen).

Fig. 18. Pietrele: pot with incision on the bottom(Photo S. Hansen).

Figurines in Pietrele> Copper age ideology

13

Fig. 19. Potsherds from Saxony and Bohemia (af-ter Spatz 2003).

Fig. 20. Clay house from Sultana with gold objects(after Hansen 2007).

Fig. 21. Clay house from Pietrele (picture: D. Spânu).

.