Greek statuary: Archaic to Early & High Classical

-

Upload

lorna-gray -

Category

Education

-

view

2.351 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Greek statuary: Archaic to Early & High Classical

With his ‘Vitruvian man’, Da Vinci explored the ideal proportions of the human body. Photoshop is used to create idealised, ‘perfect’ images in mass-media.Polykleitos, a Greek sculptor (c. 450-440 B.C.E.) also wanted to investigate these ideal proportions with his Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) or Canon.

Look at the images & think for 1 minute what the essential idea of today’s lesson is.

Greek statuary: from Archaic to Early & High Classical

Beauty consists in the proportions, not of the elements, but of the parts, that is to say, of finger

to finger, and of all the fingers to the palm and the wrist, and of these to the forearm, and of the

forearm to the upper arm, and of all the other parts to each other.

– Galen, writing in the 2nd century AD, summarising Polykleitos’s idea of relating beauty

to ratio.

BIG PICTURE

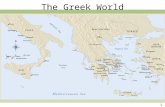

Starting point - 8th century BCE: the poleis of Classical Greece began to take shape; the Greeks broke out of their isolation and once again began to trade with cities both in the east and the west (including Egypt); Homer’s epic poems were recorded in written form; the Olympic Games were established.

Archaic periodMonumental statuary returns. Not naturalistic, influence of Egypt still noticeable.The Archaic smile indicates life, not humour.

480 BCE Classical period beginsEarly, High (Late)Monumental statuary is more naturalistic and seeks to find the ideal depiction of motion.Perfection. Proportion. Balance. Counter-balance.

Archaic

Kouros, ca. 600 bce. Marble. ca. 6’ tall. Metropolitan Museumof Art, New York.

Funerary statue. Known as the ‘New York Kouros’.

Egyptian influence: rigidly frontal, left foot slightly advanced; arms held beside the body, fists clenched, thumbs forward; hips are V-shaped ridges; triangular shape of head & hair; eyes, nose, mouth in the front of the face, ears on the side (carved from a block of marble according to Egyptian technique.

Greek innovation: the figure is liberated from the marble block. The artist was not interested in timeless permanence, but in finding ways to realistically depicting motion.

Archaic

Calf bearer, dedicated by Rhonbos on the Acropolis, Athens,Greece, ca. 560 BCE. Marble, Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Votive statue: the Calf bearer or moschophoros (found in fragments on the Athenian Acropolis). Its inscribed base (not visible in the photograph) states that a man named Rhonbos dedicated the statue to Athena, most probably the calf bearer himself. Left foot advanced, but he has a beard (not a young man). The figure wears a thin cloak but is otherwise nude. (The sculptor adhered to the artistic convention of male nudity, attributing to the calf bearer the noble perfection that nudity suggests, while also indicating that this mature gentleman is clothed, as any respectable citizen would be in this context.) Archaic love of pattern is seen in the way man and animal are represented together. The calf ’s legs and the calf bearer’s arms form a definite X that unites the two bodies both physically and formally. The calf bearer’s face differs a lot from those of earlier Greek statues (and those of Egypt) in one notable way. The man smiles, or at least seems to. From this time on, Archaic Greek statues always smile, even in the most inappropriate contexts (when dying for example). This so-called Archaic smile seems to be the Archaic sculptor’s way of indicating that the person portrayed is alive. By adopting this convention, the Greek artist signaled a very different intention to any Egyptian counterpart.

Archaic

Kroisos, from Anavysos, Greece, ca. 530 BCE. Marble, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

The Anavysos Kouros, funerary statue for a young man who died in battle in ca 530 BCE. Archaic smile.Originally, sclupture was painted. Without rejecting the Egyptian stance, the artist has tried to render the human body in a more naturalistic manner: the head is not too large for the body, the face is more rounded, with swelling cheeks replacing the flat planes of the earlier New York Kouros. The hair falls naturally over the back. Rounded hips replace the V-shaped ridges of the New York Kouros.

The Archaic smile Dying warrior, from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina, Greece, ca. 490 BCE. Marble, Glyptothek, Munich. The statues of the west pediment of the early-fifth-century BCE temple at Aegina exhibit Archaic features. This fallen, dying warrior still has an Archaic smile on his face.

Art historians mark the beginning of the Classical Greek age from a historicalevent: the defeat in 480 BCE of the Persian invaders of Greece by the alliedHellenic city-states. Shortly after the Persians occupied and sacked Athens in 480 BCE , the Greeks won a decisive naval victory over the Persians at Salamis.

Early Classical sculptors were also the first to break away from the rigid and unnatural Egyptian-inspired pose of the Archaic kouroi.

From Archaic to the Early Classical

From Archaic to Early & High Classical (1 of 3)

Kritios Boy, from the Acropolis, Athens, Greece, c. 480 BCE. Marble. Acropolis Museum,Athens.

Even though it is not life-size, this marble statue known as the Kritios Boy (so titled because it was once thought the sculptor Kritios carved it) is one of the most important works of Greek sculpture: it is the first statue to show how a person naturally stands. The sculptor depicted the shifting of weight from one leg to the other (contrapposto). Real people do not stand in the stiff-legged pose of the kouroi and korai or their Egyptian predecessors. Humans shift their weight and the position of the main body parts around the vertical but flexible axis of the spine. When humans move, the body’s elastic musculoskeletal structure dictates a harmonious, smooth motion of all its elements. The sculptor of the KritiosBoy was among the first to understand this fact and to represent it in statuary. The youth has a slight dip to the right hip, indicating the shifting of weight onto his left leg. His right leg is bent, at ease. The headalso turns slightly to the right and tilts, breaking the unwritten ruleof frontality dictating the form of almost all earlier statues.

This weight shift, which art historians describe as contrapposto (counterbalance), separates Classical from Archaic Greek statuary.

The Archaic smile is gone.

From Archaic to Early & High Classical (2 of 3)

Warrior, from the sea offRiace, Italy, c. 460–450 BCE.Bronze, Museo ArcheologicoNazionale, Reggio Calabria.

The Riace Bronzes: the innovations of the Kritios Boy were carried even further in the bronze statue of a warrior found in the sea near Riace at the “toe” of the Italian “boot.” The weight shift (contrapposto) is more pronounced (noticeable) than in the Kritios Boy. The warrior’s head turns more forcefully to the right, his shoulders tilt, his hips swing more markedly, and his arms have been freed from the body.

Natural motion in space has replaced Archaic frontality and rigidity.

This is one of a pair of statues divers accidentally discovered in the cargo of a ship that sank in antiquity on its way from Greece probably to Rome, where Greek sculpture was much admired. Known as the Riace Bronzes, they had to undergo several years of cleaning and restoration after nearly two millennia of submersion in salt water, but they are nearly intact. The statue shown here lacks only its shield, spear, and helmet. It is a masterpiece of ‘hollow-casting’ with inlaid eyes, silver teeth and eyelashes, and copper lips & nipples.

From Archaic to Early & High Classical (3 of 3)

Zeus (or Poseidon?), from the sea off Cape Artemision, Greece, ca. 460–450 BCE. Bronze.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

The Artemision Zeus: the male human form in motion is the subject of another Early Classical bronze statue , which, like the Riace warrior, divers found in an ancient shipwreck, this time off the coast of Greece itself at Cape Artemision.

Both arms are boldly extended, and the right heel is raised off the ground, emphasising thelightness and stability of the statue.

Who is it?The bearded god once hurled a weapon held in his right hand, probably a thunderbolt, in which case he is Zeus. A less likely suggestion is that this is Poseidon with his trident. The pose could be employed equally well for a javelin thrower.

http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/classical-greek.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=EAR9RAMg9NY&noredirect=1

Watch, listen and then answer the question:

What did ‘perfection’ mean for the Ancient (Early & High Classical) Greeks?

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear Bearer). Roman marblecopy from Pompeii, Italy, after a bronze original of ca. 450–440 bce, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.

Polykleitos sought to portray the perfect man and to imposeorder on human movement. He achieved his goals by employing harmonic proportions and a system of cross balance for all parts of the body.

Mathematical precision in the proportions of the human body; mathematical relationship of each part of the body to each other, and to the whole; harmony through ratio.

The Doryphoros by Polykleitos One of the most frequently copied Greek statues was the Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) by the sculptor Polykleitos, whose work epitomizes the intellectual rigour of Classical Greek art. The best marble replica stood in a palaestra at Pompeii, where it served as a model for Roman athletes.The Doryphoros was the embodiment of Polykleitos’s vision of the ideal statue of a nude male athlete or warrior. In fact, the sculptor made it as a demonstration piece to accompany a treatise on the subject. ‘Spear Bearer’ is a modern descriptive title for the statue. The name Polykleitos assigned to it was Canon.The Doryphoros is the culmination of the evolution in Greek statuary from the Archaic kouros to the Kritios Boy to the Riace warrior.The contrapposto is more pronounced than ever before in a standing statue, but Polykleitos was not content with simply rendering a figure that stood naturally. His aim was to impose order on human movement, to make it “beautiful,” to “perfect” it. He achieved this through a system of cross balance. What appears at first to be a casually natural pose is, in fact, the result of an extremely complex and subtle organization of the figure’s various parts. Note, for instance, how the statue’s straight-hanging arm echoes the rigid supporting leg, providing the figure’s right side with the columnar stability needed to anchor the left side’s dynamically flexed limbs. If read anatomically, however, the tensed and relaxed limbs may be seen to oppose each other diagonally—the right arm and the left leg are relaxed, and the tensed supporting leg opposes the flexed arm, which held a spear. Similarly, the head turns to the right while the hips twist slightly to the left. And although the Doryphoros seems to take a step forward, the figure does not move. This dynamic asymmetrical balance, this motion while at rest, and the resulting harmony of opposites are the essence of the Polykleitan style.

Sources and extra information:

Gardner’s Art through the Ages

http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org

http://www.essential-humanities.net

http://www.ancient-greece.org/resources/timeline.html