Greek Architecture 0028j Shaw0029

-

Upload

alexarcheologia -

Category

Documents

-

view

11 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Greek Architecture 0028j Shaw0029

-

N.B. Not on syllabus, but useful in anydiscussion of the origins of the Doricorder.

DESCRIPTION

Column plan 15 5, very long cellaopen at front, with thresholds for gatesbetween the antae and a column inbetween; 10 columns down the centre ofthe cella and two more in theopisthodomos (of which this is the earli-est example) to assist the mud-brickwalls in supporting the roof. The pen-tastyle (5 column) faade is thereforelogical, the positions of the five corre-sponding to the lines of the cella walls,the central colonnade, and the flankcolumns. The intercolumniations arehuge in comparison with the columndiameters (because wooden architrave isstrong but light) and no angle contrac-tion is present. Only the isolated columnfootings were made of stone, thecolumns and entablature being wooden.Terracotta was used for much of the dec-oration, including triglyphs and metopes;the triglyphs do not survive (thoughsome smaller ones from a nearby templedo), but some metopes are intact and

show they were painted. In the sixthcentury the temple seems to have beenrenovated; probably there was a pedi-

ment only at thefront earlier, andthe rebuildingreplaced a hip roofat the rear with asecond pediment.In the Hellenisticperiod the col-umn footingswere connected toform a stylobate,and the columnsgradually replacedin stone.

SIGNIFICANCE

Interesting as the earliest example of aDoric temple, yet it has all the majorfeatures of the developed order: thetriglyph frieze, mutular cornice, guttaeetc. According to Vitruvius these fea-tures reflect the origins of the Doricorder in a wooden architecture, and theirpresence at Thermon in a basicallywooden temple serves to lend credibilityto this theory. In any case it is moststriking that the decorative detailsof the Doric ordercome into

beingovernight andwith

very few exceptionsare reproducedfaithfully on every Doric temple.

DATE: c. 630 B.C. ORDER: DORIC

1. (a) plan (b) elevation

-

DESCRIPTION

Column plan 16 6, stereobateonly has two steps, and wideintercolumniations which suggesta wooden architrave. Thecolumns were probably all wood-en at first; the present stonecolumns display a wide variety ofshape and width (e.g. two adja-cent ones have diameters of 3' 3"and 4' 2"); some are monolithic,others not, and the echinus dis-plays all profiles from the archaicbulge to the classical near-straightline, and even theRoman/Hellenistic quar-ter-circle.Conclusion: thecolumns werereplaced gradual-ly in stone over aperiod of about800 years as andwhen fundsbecame available.Cuttings in thestylobate, nowhidden by thestone columns,reveal that thewooden columnshad a base diame-ter of only 3' 2".Since the heightwas obviously thesame, the newstone columns(perversely, as faras structuralstrength is con-cerned) werestouter than theirwooden forbears.

There is no trace of a stone entab-lature. The wide intercolumnia-tions show that architrave andentablature were wooden; anglecontraction demonstrates thepresence of a triglyph frieze. Verythick cella walls (upper part madeof mud-brick) were protected upto 3" on the outside byorthostates. The ends of thepronaos and opisthodomos wallswere encased in timber for addedstrength, thus providing a proto-type for antae. The interiorcolumns were arranged in two

rows of eight, aligned with theouter columns (so roof beamscould receive support from outerand inner columns); they dividethe width of the temple into three,so the cella walls were not neces-sary to support the roof. Alternatecolumns were originally attachedto the cella walls by spur-walls togive the latter extra strength; laterthese spurs were cut away. TheOlympia Museum still has thecircular terracotta acroteria whichhad a diameter of 7' 7".

SIGNIFICANCE

The most notable of allthe early Doric peripteraltemples; it has plenty ofinstances of the woodenarchitecture that charac-terises the origins of theDoric order. Being somuch earlier than thegreat temple of Zeuswhose temple jointlywith Hera this originallywasit occupies a moreancient holy spot than thelater temple. The way inwhich the columns werereplaced in stone is alsointeresting; it shows thatit was regarded as a desir-able programme, but noturgent, and there is noheritage view of archi-tecture requiring the newcolumns to conform tooutmoded designs.

2

DATE: c. 600 B.C. ORDER: DORIC

3. (a) plan (b) elevation

-

DESCRIPTION

In the sixth centuryCorinth was a flourishingcommercial centre. Atemple of Apollo wasbuilt in the lower city;seven of its limestonecolumns remain standing,and much of the stylobateis still visible. It has beenpossible to establish theoriginal layout as being 6x 15 columns; these long propor-tions are explained by the factthat it has a double cella, withone room facing east and theother west. Another unusual fea-ture is that the column shafts aremonoliths, not made up not ofseparate drums; they also lackentasisi.e. vertical curvature orswellingso that their basic

shape is that of a truncated cone.The capitals are carved from sep-arate blocks, and the echinus is

less bulbous than on some earliertemples. In accordance with usualpractice on the mainland, theintercolumniations and columndiameters are smaller on theflanks than on the faades (seediagram 36b). Angle contractionis also present on both flanks andfaades, but even so the corner

metopes must have been sometwo inches wider than the rest.The internal roof was supported

by two rows of columns.

The stylobate was curvedupwards. This is some-times referred to as anoptical refinement but isquite likely to have beenintended as a way of shed-ding rainwater.

SIGNIFICANCE

One of the oldest surviving tem-ples in Greece. The long propor-tions, shape of the echinus andarrangement of columns are typi-cal of the mid-sixth century BC;the use of monolithic columnshafts is almost unique on a tem-ple of this size.

3

DATE: 650 B.C. ORDER: DORIC

4. Corinth, temple of Apollo

-

4DESCRIPTION

Column plan: 18 9, with 8columns down the centre, oneinternal intercolumniation beingwider than the rest; the pronaos istristyle in-antis, the rear having aclosed adyton instead of anopisthodomos. Very wide pteronmakes this temple almost pseudo-dipteral. There is no angle con-traction, and the flanks showwider spacing than the faades

(the opposite of the normal archa-ic practice of having wider inter-columniations on the faades).The internal columns are thesame height as the external ones,though the inner columns weresurrounded at the base by slabsfor a raised cella floor to a heightof 1' 8 ", which was never fluted.

The decorative treatment of thecapitals in this and the nearbytemple of Athene surpasses anyother known examples. The flut-ing terminates in Ionic semi-cir-cles below a fillet; the nine capi-tals on the west front (i.e. therear) have at least seven differentdesigns applied in relief to theunderside of the echinus, includ-ing half-rounds, rosette-and-lotus,guilloche, lotus-and-palmette etc.The antae are also highly unusual,with what are effectively capitals,

flaring widely and carrying tinycylinders reminiscent of proto-Ionic forms.

Above the architrave, elaborateIonic mouldings are found inplace of Doric regulae & guttae:an ovolo surmounted by a con-cave range of drooping petals.There was probably a triglyph

frieze above this as normal.Notice also the pronounced enta-sis and exaggerated diminution ofthe upper column diameters giv-ing a strongly cigar-shaped col-umn profile.

SIGNIFICANCE

Paestum was a Greek city in Italy(Magna Graecia). Its variationson the normally rigid Doric canonhave been described as 'barbaric'

or 'provincial'; however bear inmind that this is still early yearsfor the Doric order, and the latertemple of Hera at Paestum con-forms fully to the 'proper' order.The peculiarities here can there-fore be seen as deriving at least asmuch from free-wheeling experi-mentation as from ignorance.

DATE: c. 550-500 BC ORDER: DORIC

5.

-

5DESCRIPTION

This temple replaced its predeces-sor, which burnt down in 548 BC.The site is particularly difficult tobuild on, being a sheer mountain-side. The northern flank restsdirectly on the bedrock, but thesouthern side required to beraised on a terrace some 200 feetlong and 1015 feet high. Workwas begun at the west end (i.e.the rear) and proceeded usingporos limestone even for the ped-imental sculptures in high relief.After the military defeat of thedemocrats in Athens in 513 BC,their leader Cleisthenes came toDelphi and took over the work,completing the east end in Parian

marble. This he did in an attemptto win the support of the Delphicpriests, who had previously puthim and his family (theAlcmaeonids) under a curse forimpiety (this being the reasonfor his exile from Athens). Thistemple was destroyed by a land-slide in 373 BC and subsequentlyrebuilt on almost exactly thesame plan; it is the remains of thefourth century building, in hardgrey limestone, that can now beseen on the site. The column plan,as at Corinth, is 6 x 15, the lengthhere being explained by the intro-duction of an adyton into theplan; this is an inner chamber,here underground, where thePythian priestess sat on the tripodand delivered her oracle.

SIGNIFICANCE

Very little survives of the decora-tion that was so admired in antiq-uity. The significance of this tem-ple resides not so much in itsarchitectural design as in the factthat it was built at all on such adifficult site. The awe in which itwas held by the ancient Greeks iswell illustrated by the myths thatgrew up around it, including thestory told by Pausanias that itspredecessors were temples builtof laurel, beeswax, and bronze.

DATE: c. 536505 B.C. ORDER: DORIC

6. Delphi, temple of Apollo, east elevation (reconstruction)

-

6DESCRIPTION

Column plan: 13 6 externalcolonnade (very conventional),but has highly unconventionalprostyle portico in the Ionicorder; there is no opisthodomos atrear (temple too small, perhaps).Regular column spacing all

round, and no angle contraction.Highly decorative Doric capitalsas on the First Paestum Temple ofHera: above the semi-circularflute-tops there is an astragalcarved in bead-and-reel; the neck-ing has a deep scotia filled withdrooping petals, two or three toeach flute; again relief mouldingsappear on the undersides of theechinus. The Ionic order of theprostyle portico had 28 flutes butarrises instead of fillets; the baseshave a circular disc below a atorus. The sandstone capitals areelongated in the archaic manner

with a single bordering astragal;unusually the inner part of thevolute is replaced by a large con-vex eye; the ovolo below iscarved in archaic egg-and-dart;above, a pronounced abacus.

Above the architrave, in place ofthe Doric regulae and guttae,there is an ovolo in egg-and-dart;

the triglyph frieze is unusual inthat the triglyphs are all of sand-stone with the prismatic facesslightly concave to give greatersharpness at the edges, and theseare simply inlaid into the lime-stone frieze blocks, the gapsbetween serving as metopes. Thelack of angle contraction meansextra-wide metopes at the cor-ners.

The most unusual feature of thistemple is the cornice. Directly onthe triglyph frieze rest two cours-es of sandstone, the lower carvedin a serpentine pattern, the upper

with egg-and-dart; these go allround the temple and form theonly cornice below the pedi-ments. But on the flanks, insteadof the normal cornice withmutules, there are overhangingeaves of limestone, the soffit cof-fered in the manner of wood-work; on the faades the eavesare bent and carried up the slopes,though the bend appears only inthe soffit and does not affect theupper outline. The panel of eachsoffit was filled with a sandstoneplaque carved with a star in relief.The crowning sima is the earliestknown example of a cyma recta(wave) moulding being used inthis position; this is of sandstoneand has anthemion (lotus-and-pal-mette) in relief.

SIGNIFICANCE

Like the First Temple of Hera,represents early, provincial exper-imentation with the Orders, whichseem not to have become sostrictly prescribed in their detailsaway from mainland Greece.Note that there is no reason forthe preference of Ionic features incertain locations on the temples;for example, the Ionic prostyleportico is not exploited for itstaller, slenderer proportions;moreover it is not even separatedfrom the Doric exterior order andwould have been clearly visiblealongside it. The designers appearnot to have been worried by acontradiction which might havegiven a mainland Greek architectpalpitations!

DATE: c. 500 B.C. ORDER: DORIC

7. The three temples at Paestum: elevations: (a), (b), (c), (d), as in fig. 4, with the firsttemple of Hera restored above architrave level on the basis of the temple of Athene.

-

DESCRIPTION

This is a particularly well-pre-served temple. It was built oflocal limestone covered in a thinlayer of stucco, and its pedimentfigures were made of Parian mar-

ble. The column plan is 6 x 12and seems to incorporate an earlyattempt at systematic proportions,with the columns diameters being3 Doric feet and the intercolumni-ations (on the fronts at any rate) 8Doric feet. The corner columnsare thickened slightly, possibly ascompensation for the fact that the

columns of the faade are of thesame diameter as those of theflanks. As at Corinth, the shaftsare monolithic, with the exceptionof three adjacent columns of thenorth flank, which were presum-ably left out to allow easieraccess to the interior while build-

ing proceeded, then slotted inafterwards in the usual manner ofdrums.

The interior roof was supportedby two rows of two-tiered Doriccolumns. The taper of thecolumns is continuous from thebottom to the top, so that thelower diameter of the upper row

in less than the upper diameter ofthe lower, because of the interrup-tion of the intervening architrave.The architrave was decoratedwith regulae and guttae eventhough there is no correspondingtriglyph frieze; unusually, it alsosupported a gallery, accessed byladders. Note on the plan theslight irregularity of the off-centredoorway between cella andopisthodomos, which was clearlyan afterthought, as it cuts throughthe lower courses of the interven-ing wall.

SIGNIFICANCE

Dinsmoor calls this the most per-fectly developed of the late archa-ic temples in European Hellas.This judgment is probably basedon the temples simple but har-monious proportions; the fact thatthe pediment sculpture also sur-vives and is widely admired forits quality is also an importantfactor.

7

DATE: completed c. 490 B.C. ORDER: DORIC

8. The temple of Aphaia, Aegina

-

8DESCRIPTION

Column plan: 13 6 columns.One of the largest Doric templesconstructed on the mainland.Built of local limestone (poorquality) covered with stucco;Parian marble was imported forthe sculptured metopes and pedi-ment figures; acroteria were ofbronze. The plan shows anapproach ramp. The archaic prac-tice of varying the intercolumnia-tions on the flank and frontcolonnades is scrapped in favourof equal spacings all round(except for angle contractions),but is echoed by a peculiarity ofthe column diameters, which are1" wider on the fronts.

The architect, Libon, seems tohave been interested in creating asystem of ideal proportions,since the column height has been

established as 32Doric feet, whichequals two interco-lumniations of 16feet, and the abacuswidth was 8 feet.There were sixsculpted metopesover the columns ofthe porches. Foldinggates between thepronaos columns ledtowards an impres-sive central door,which gave access toa cella with a doubletwo-tier Doriccolonnade of sevencolumns. A stonescreen across the cella at the sec-ond column in restricted access tothe cult statue. The screen contin-ued between the second and fifthcolumns at the sides, and carriedon as a bronze grille from thefifth to the seventh column.

Either side of the greatdoor, steps led up to agallery which wasaligned at the height ofthe architrave betweenthe two tiers of the inter-nal colonnade.

The cult statue of Zeuswas installed by Pheidiasabout 448 B.C. andinvolved making alter-ations to the building inorder to accommodate itsbulk. Even then, itspedestal came up flushagainst the internalcolonnade. It came to becelebrated as one of theseven wonders of theworld.

SIGNIFICANCE

The best example of a canonicalDoric temple. In every way itembodies the severity and gravityof Doric architecture; this is rein-forced by the sculpturesnosculpted metopes on the outside,and the East pediment with itsvertical composition closelyechoes the columns of the faade.Only the West pediment and thesculpted metopes of the porchesslightly soften the predominanceof verticals and horizontals. Thelocation of this temple provides anew focus for the Altis, leavingthe old temple sidelined; laterbuildings, such as stoae, clearlylook to the temple of Zeus as theprincipal building of the precinct.

DATE: c. 468-460 BC ORDER: DORIC

9. (a) Temple of Zeus at Olympia and (b) Parthenon atAthens; plans at a uniform scale

10. (a) Temple of Zeus at Olympia and (b) Parthenonat Athens; sections at a uniform scale

-

9DESCRIPTION

Column plan 14 6, with anglecontraction on the flanks as wellas the fronts. Pronaos andopisthodomos are present, eachdistyle in-antis; the cella has adouble two-tiered Doric colon-nade of seven columns; the uppercolumns rest upon an architravewhich has a continuous crowningmoulding in place of the usualregulae and guttae. The lowerdiameter of the upper columns isconsiderably less than the upperdiameter of the lower ones, sothat the diminution from bottomto top is continuous. The columnsof the external order are unusualin having 24 flutes; furthermorethe lower range of internal

columns has 20 and the upper 16.There are two recesses betweenthe pronaos and cella, one ofwhich had a staircase, which musthave led to the roof since there isno trace of a gallery.

SIGNIFICANCE

One of the best preserved ofGreek temples, it illustrates by itsrelative conformity the end ofWest Greek experimentation withthe orders, just before the archi-tects of the mainland begin toachieve new successes by virtueof similar, but rational andrestrained, hybridisation of theorders. Also note how the oldertemple of Hera is not demol-ished, but its replacement is sim-

ply built alongside.

DATE: c. 460 BC ORDER: DORIC

11. The three temples atPaestum: sections: (a), (b), (c),

(d) as in fig. 4, with the firsttemple of Hera restored as in

fig. 5

-

10

DESCRIPTION

Designed and begun apparentlyby Iktinos shortly before theParthenon took him away toAthens, so causing work to dragon far longer than intended.Situated in a remote spot in themountains, the temple was com-missioned in the wake of a plagueby the local Phigalians in fulfil-ment of a vow to ApolloEpikourios (the Healer). A brittlegrey local limestone was used forthe building with marble fordetails.

This temple is very unusual inseveral respects. It is alignednorth-south instead of the normaleast-west (possibly because of the

awkward local terrain), and has avery long 15 6 column plan,which accommodates an addition-al room (adyton) behind the cella,entered from the flank colonnadeby an east-facing door. The exter-nal order is Doric; the northfaade has heavier-proportionedcolumns than the other threesides. The flank intercolumnia-tions are slightly shorter, in accor-dance with archaic practice; alsoarchaic are the triple incisionsbelow the necking of the capitals.

Yet there are refinements too,such as the little sunken panels atthe bottom of each riser in thestereobate. There were six sculpt-ed metopes at each end, as atOlympia, and pedimental figures,which have disappeared.

It is the interior which is mostinteresting. A continuous Ionicfrieze (depicting Greeks vs.Amazons, Lapiths vs. Centaurs)ran around all four walls (so that,unlike at the Parthenon, the wholefrieze could be taken in at once),supported on an internal Ionicorder of four columns either side,aligned not with the axes of theexternal columns but with themid-points of the intercolumnia-tions, so that the north pair arecuriously close to the main door-way.These Ionic columns are reallyhalf-columns, attached to thecella walls by short spur-walls (asoriginally at the OlympiaHeraion). At the southern end thespur-walls are angled, and a free-standing Corinthian column stoodbetween them (the earliest record-ed example). The intercolumnia-tions provided niches for offer-ings, and the main part of thefloor was slightly sunk, so thatthe Ionic columns appeared to beraised on their own stylobate.

The design of the Ionic orderused here is unique. The bases arewidely flared, and quite unlikeany others: perhaps the designproved impractical. The capitalshave volutes connected by anupwardly-curved astragal; this,and the curious fact that the axisof each capital is some 2" furtherback than the axis of the column

DATE: c. 450-425 BC ORDER: DORIC

12. Temple of Apollo at Bassai: plan

13. Temple of Apollo at Bassai: restored perspective of cella

-

itself, can perhaps be explained asan attempt to compensate for theforeshortening caused by thesteep angle of view. (An unusedcapital was recovered nearby,with a conventional flat linecon-necting the volute tops.) There isno abacus above, and instead ofthe egg-and-dart echinus there isjust a cyma reversa (wave)moulding.

Also notable is the fact that eachcapital consists of one full voluteface adjoined by two half-volutes,angled outwards in the manner ofthe usual angle capital. Clearlythe volute had to face towards thecentre, as otherwise it would notbe parallel with the line of thearchitrave; the preference for thevolute at the side over the usualbaluster is possibly due to thedifficulty of grafting a half-balus-ter onto a spur-wall. In any casethe resulting design is againunique, and shows that the archi-tect was not afraid to make inno-vations to deal with particularproblems.

As the viewer approached theend pair of columns, the angle

would conceal the spurs and pres-ent the appearance of two free-standing columns. This woulddiminish the otherwise odd singu-larity of the central column,though its unique capital designreinforced it. This was the earliestknown instance of a Corinthiancapital on a building; not ofcourse in its most developedform, but it has the essentials, i.e.a square abacus with concavesides, the corners supported byfour volutes which scroll upwardsfrom the base of an inverted bell,

which is girdled by acanthusleaves and topped on each of thefour sides by a palmette. It isgenerally accepted that the twoflanking columns also had thesame Corinthian capital, eventhough their bases are the sameas all the others, whereas thebase of the central column is dif-ferent. Probably the architect haddifficulty designing a variant ofhis Ionic capital for the diagonalspur-wall that would presentfaces parallel to the line of thearchitrave, so improvised a newdesign which was then applied tothe central column as well.

SIGNIFICANCE

Note the implications for theprocess of commissioning a tem-ple: a small, relatively unimpor-tant town is able to commissionan Athenian architect to come andwork for them; he in turn seemsprepared to work with somestrange guidelines (whether theywere dictated by local topogra-phy, cultic requirements, or otherunknown factors) giving rise toseveral unique features, for whatmay have been an interestingchallenge; but after a few yearshe leaves Bassai in order to takeon a far more important and chal-lenging project. The probable linkwith Iktinos is also interesting forthe meaningful comparisons thatcan be made between Bassai and,e.g., the Parthenon.

The origin of the Corinthian orderis also, of course, most signifi-cant, and can be seen as theresponse to a particular designproblem concerned with angles ofview in an interior space.

It was once thought that therewere pedimental sculptures, but ithas more recently been shownthat the gables were left empty. 11

14. Temple of Apollo at Bassai: Ionic and Corinthian orders from cella: (a) plan look -ing up; (b) elevation; (c), (d) Ionic angle capital (elevation) from the temple by the

Ilissos in Athens (c. 450 B.C.); (e) normal Corinthian capital (Roman)

15. Bassai: Ionic and Corinthian orders

-

12

DATE: begun c. 449 BC ORDER: DORIC

DESCRIPTION

This temple was begun shortlybefore the Parthenon but maywell have been completed after-wards, as the interior looks as if ithas been redesigned in the lightof the larger temple. Two cultstatues by Alkamenes stood with-in: it was dedicated jointly toAthene and Hephaistos (aspatrons of craftsmen; hence thesiting of the temple in the agoranear where the bronze-castersworked). Column plan 13 6.There is an attempt at creating asystem of ideal proportions, but itdoes not work as successfully asin the Parthenon. The columnsare too thin compared with theheavy entablature, though thetemple stands on a low hill over-looking the agora, and the effectis diminished when seen frombelow; indeed it may have beenintended to design the templewith this one particular viewpointin mind. The temple is builtentirely of Pentelic marble,except for wooden roof beams,terracotta roof tiles, and the bot-tom step of the stereobate whichis of a darker-coloured limestoneand blends in with the ground,effectively 'disappearing'. Thetemple has a wealth of opticalrefinements, surpassing even theParthenon in this respect, thoughthe result is not as satisfactory.

The original intention appears tohave been to create a cella thatwas longer and narrower than theone that was eventually provided;the walls were covered in plaster

ready to receive mural paintings.Possibly under the influence ofIktinos it was decided instead tohave an internal two-tier colon-nade (quite unnecessary for sup-porting the roof) with a return ofone central column to form ahorseshoe-shaped space for thedisplay of the statuesa minia-ture version of the internalarrangement used in theParthenon. In such a reducedspace, however, the result israther different: the columns areonly about a foot from the walls,effectively creating niches (as atBassai) rather than an ambulatory.There are several ideas takenfrom the Ionic order. Along theexternal base of the cella wallthere is an Ionic moulding, anidea possibly borrowed from theOlder Parthenon. Most interest-ingly there is a continuous Ionicfrieze running above the archi-traves of the porcheslike theParthenon, except that here itdoes not run down the sides ofthe cella as well. It even has anIonic moulding crowning thearchitrave below, where theParthenon retains the Doric regu-lae and guttae. At the rear thefrieze runs just between the antae;but (and here note that thepronaos antae and columns arealigned exactly with the third col-umn in on the flanks) the frieze inthe pronaos is extended across thewidth of the north and south peri-styles to join with the inner faceof the outer entablature, thusdefining the area enclosed by theouter columns in front of thepronaos as a new space, at least at

the height ofthe frieze.This internaldefinition isreinforced onthe outsideby virtue ofthe fact thatthe onlycarvedmetopes, ofwhich thereare 18, arethose whichenclose thisarea; theyalso facetowards theagora and theintended view-point.

The pediments were providedwith sculpture, which has largelydisappeared, as have the cult stat-ues, although copies in relief ofthe latter, along with blocks of thepedestal of Eleusinian stone, havebeen found.

SIGNIFICANCE

Although the colonnade wasremoved when the building wasconverted to a church, thisremains the best preserved of allGreek temples. It is interesting asa counterpart to the Parthenonand shows the influence ofIktinos in its replanning. It showsthat the refinements and Ionicdetails of the Parthenon were farfrom unprecedented, indeed weresomewhat restrained in compari-son.

16. Hephaisteion, Athens:plan

-

13

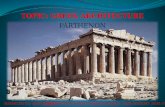

BACKGROUND

After the First Persian War andthe single-handed Athenian victo-ry at Marathon in 490, a large-scale rebuilding of the Acropoliswas initiated, using marble fromthe newly-opened quarry at near-by Mount Pentelikon. In using thefinest quality building materialthroughout, the proj-ect aimed at a richnessunrivalled in the Greekworld. A new templewas begun on the siteof the later Parthenon.It was to be hexastyleDoric but with Ionicfeatures and tetrastyleprostyle porches; theplatform on which itwould be built itselfwas a massive project,252' 103' of solidlimestone, at one cor-ner reaching a heightof 35' above bedrock.In the Second PersianWar the Persiansinvaded Greece anddestroyed templeswherever they went.The Older Parthenonwas ruined eventhough it had onlyattained a height oftwo to four columndrums (5'10'). The site was leftderelict for thirty years in accor-dance which the oath which theGreeks all swore after the victoryof Plataia in 479 B.C. not torebuild the sanctuaries sacked bythe Persians 'as memorials to theimpiety of the barbarians'. Duringthose thirty years Athens' fortunesprospered as head of the DelianLeague, and when peace was

finally negotiated between theleague and the Persians in 449B.C., Perikles annulled the oathand instigated a new buildingprogramme on the Acropoliswhich would reflect by its mag-nificence the new supremacy ofAthens, and thank the city'spatron goddess for her favourwith unstinting richness.

NAME

The temple was known officiallyas the temple of Athene Polias,but since this was also the nameof the temple on the north side ofthe acropolis which contained thesacred xoanon (later theErechtheion), it was usuallycalled the Hecatompedon

(Hundred-footer), a nameapplied not only to the OlderParthenon, but to its oldPeisistratid ancestor too. Thename Parthenon originallyreferred only to the back room,but was applied to the wholebuilding after about a century.

DESCRIPTION

The plan is more sump-tuous than any othermainland temple. Theexisting base of theOlder Parthenon wasextended to the northresulting in a stylobate228' 1" 101' 4" (i.e.wider but shorter than itsunfinished predecessor)to accommodate a col-umn plan of 17 8. Thewide dimension wasplanned to give a widernaos and improve thesetting of the great statuewithin. The exact dimen-sions of the stylobatewere determined by theperistyle elements (num-ber, spacing and diameterof columns), and thegreatest considerationhere was given toeconomising by judiciousre-use of those parts of

the old temple which were stillserviceable. Hence the basic col-umn diameter of 6' 3", inheritedfrom the Older Parthenon. Theintercolumniation related to thisin the ratio of 9:4 (except at theexcessively-contracted corners).The 9:4 ratio is also seen in thelength width of the stylobate,and also the stylobate widthheight of the order.

DATE: 447-438 BC ORDER: DORIC

17. (a) Temple of Zeus at Olympia and (b) Parthenon at Athens;elevations at a uniform scale

-

The columns are nearly 5 lowerdiameters high, and the curve ofthe echinus is barely perceptible.The triglyph frieze on the faadesshows continuous gradation in thewidths of the metopes with thewidest at the centre, so that notriglyph on either faade is exact-ly centred over a column. Thefasciae above the triglyphs andmetopes have a beaded astragalas extra decoration, The tympa-num was recessed 8" behind theplane of the frieze to give moreroom for the pediment sculptures.The raking sima has a special'Periclean' profile; the roof tileswere made of marble and narrow-er than the usual terracotta ones,so that on the flanks, the antefixesare unusual in that only everyother is a true antefix, the otheractually concealing two rows ofcover-tiles. The acroteria werehuge openwork marble creations9' high, consisting of stems, ten-drils, acanthus and great crown-ing palmettes.

Within the peristyle, the twohexastyle porticoes were raisedon two steps. The West porch re-used the corresponding columnsfrom the Older Parthenon, thoughit needed six of that templeseight, and when it came to theEast porch it was decided not tomake another six of the same 5'7" diameter but to create a newset only 5' 4" wide, making thesecolumns over 6 lower diametershigh.

The architrave above the columnsof the porches was surmountedby the continuous Ionic frieze,which ran around the sides of thebuilding as well. Above thecolumns of the porches, thearchitrave is crowned with theusual Doric regulae and guttaeeven though there were no

triglyphs above; however on theflanks there were no columnseither, so that triglyphs becameproblematical in that position.Here the frieze runs upon a sim-ple band of the height of a com-bined taenia and regula. Abovethis highly innovative frieze anextremely decorative cornice,mirrored on the inner face of themain entablature, formed a transi-tion to the marble ceiling.

The interior of the main cella hada two-tier Doric colonnade of tencolumns, forming a return fivecolumns wide across the back,thus defining a U-shaped spacefor the statue; bronze barriersfixed between the columnsrestricted access to the rear. Theportion of the floor enclosed bythe colonnade is sunk 1!/2" (as atBassae), and there was a shallowpool to contain water immediate-ly in front of the statue. The rearroom (or "Parthenon" proper) hadfour Ionic columns, since singleDoric columns would have beenwasteful of space and overpower-ing, and a two-tier colonnadewould have been absurd in such asmall space. This is another ideawhich had been tried out atBassae and would be repeated inthe Propylaia.

REFINEMENTS

According to Vitruvius these wereintended to counteract opticalillusions; it is doubtful whetherany of these illusions would actu-ally have occurred, but it is plainthat the Greeks went to consider-able trouble to eliminate most ofthe straight lines of the temple infavour of subtle curves. Perhaps itis an impression of elasticity orvitality springing from these bare-ly-perceived curves and inclina-tions that seems to endow thebuilding, even in its ruined form,

with such liveliness.

Angle contraction was originallya solution to the triglyph friezeproblem, but seems to havebecome appreciated as a refine-ment in its own right, giving theend of the colonnade a feeling ofstability and rest. The Parthenonhas twice as much contraction asnormal, but this was to help offsetthe widening effect of theoctastyle faade.

Corner columns are thicker on theouter peristyle (as in the OlderParthenon): according toVitruvius, because these columnswould be seen against the light(and indeed the inner porches areuniform). Inward inclination ofverticals, chiefly the column axes(a line produced through themwould meet about 1 !/2 milesabove the temple), giving thetemple an air of repose, solidityand strength. This had been doneon the Older Parthenon; on cer-tain Peloponnesian templesincluding Zeus at Olympia onlythe flank colonnades inclined; thecella walls similarly sometimesincline inwards, as at Bassaewhere the inner surfaces are verti-cal. Here all the walls lean insympathy with the columns,except cross-walls containingdoors, which are always strictlyvertical.

Convex stylobate, seen on muchearlier temples (e.g. Apollo atCorinth, and again the OlderParthenon), probably originallyintended as a device for sheddingrainwater. The maximum rise onthe faades is 2" and just over 4"on the flanks, the latter curvecorresponding to a circle ofradius 3!/2 miles, though the arc isin fact parabolic. The columns areof course all of uniform height, sothat the curve of the stylobate is14

-

transmitted directly to the entab-lature; the triangle of the pedi-ments is likewise constructed ofthree upward curves.

Entasis represents the only curva-ture applied to vertical lines inthe Parthenon, but here it is ofcourse the slightness of the curva-ture which is notable; earlier tem-ples such as those at Paestum hademphatically cigar-shapedcolumns. Note that some templesavoided entasis altogether, e.g.the East porch of the Erechtheion,the temple of Nike. Entasis con-veys an impression of elasticityand strength; according toVitruvius it is to offset the illu-sion which would make straight-sided columns appear concave.

PAINTING

In general the most importantparts of a temple were left free ofcolour; the Doric peristyle con-tained no colour below the capi-tals. The necking incision waspainted blue, annulets red or blue;triglyphs were always blue, thusgiving the key, since the regulaebelow and the mutules abovewere also blue, with the interven-ing members (i.e. taenia, viaebetween mutules) were red.

On the Parthenon, the red taeniahad a gold meander patternapplied to it, and the regulae agold anthemion on the blueground. Guttae were white, buthad little circles painted on thebottom. The metopes were leftwhite apart from the sculpted andpainted figures. The continuousfrieze had a blue background, ason the Nike parapet; cf. the use ofblue-black Eleusinian stone onthe Erechtheion. A cornice alwayshad an appropriate design paintedon it, e.g. the Doric hawksbeakalways bore a leaf pattern; ceiling

coffers had successive tiers ofpainted egg-and-dart, with aneight-pointed star at the centre,though the Parthenon had floraldesigns on a blue ground. TheParthenon's sima had a delicateanthemion painted on, the ante-fixes were red and blue, and thesquare area of the cornice soffit ateach corner was also decorated.

SIGNIFICANCE

The most celebrated Greek tem-ple of all, until the eighteenthcentury also the best preserved,and revered by the Romans, alongwith the other buildings of theAcropolis, as a text-book ofarchitecture. Hence many featuresof Periklean architecture arereproduced in massive quantitiesall over the Roman empire, andform the basis of Classical archi-tecture which was then rediscov-ered in the Renaissance.

The Parthenon marks the begin-ning of the process by which theold orders cross-fertilise eachother in a meaningful and func-tional way. Ionic elements areintroduced for various reasons:

F Athens had been using Ionicforms in its buildings since thesixth century, when the tyrantPeisistratos had exploited his con-nections with other Ionian tyrantsto gain Ionian building materialsand workmen;

F Athens was now proclaimingherself the "metropolis" (mother-city) of the Ionians by virtue ofher leadership of the DelianLeague;

F the flexibility and decorative-ness of the Ionic order made itespecially suitable to produce

buildings of extravagant richnessand visual appeal;

F in at least one place, theParthenon proper, the slenderIonic columns were a practicalsolution to a difficult problem.

At the same time the whole Doricorder of the Parthenon is attenuat-ed towards the proportions of theIonic, with slenderer columnsthan usual, because of theoctastyle faade. This reduces thecontradiction between the squat,severe Doric and the graceful anddecorative Ionic.

15

-

16

DESCRIPTION

Once incorrectly known as theTemple of Wingless Victory, theTemple of Athene Victory (Nike)was built on a site that hadalready been encroached upon bythe massive and ambitiousPropylaia, so its original plans,drawn up by Kallikrates at thestart of the Periklean programme,were altered to fit. Kallikrates haddesigned the temple to consist ofa cella with a pronaos distyle in-antis, and two four-columnprostyle porches front and rear(tetrastyle amphiprostyle), similarto (and apparently with its dimen-sions copied from) his earliertemple on the Ilissos.

The reduced space available forbuilding meant that this plan wastelescoped, with the pronaosbeing absorbed into the cella, andits two columns replaced by nar-row rectangular piers which alsoserved as the entrance to thecella, bronze grilles being placedbetween the piers and the antaeinstead of walls. The proportions

of the Ionic order are exceptional-ly stocky, the columns less than 8lower diameters high. This mayhave been because it was thoughtthe usual proportions would beout of keeping with the squatnessof the bastion on which the tem-ple stood, or an accommodationtowards the Doric order of thePropylaia which bordered it. Thecolumn bases have the Attic pro-file (though the lower torus iscompressed); the end columnshave specially designed versionsof the corner capital with inter-secting volutes, despite the factthat there is no flank colonnadefor them to fit in with, showingperhaps that this Ionic feature hadcome to be appreciated in its ownright. The architrave was the firstin Athens to be subdivided intothree fasciae (though the practicewas common in Asia).

Sculptural ornamentation waslavish: the frieze depicted theBattle of Plataia; there were alsopedimental groups, and as acrote-ria, golden winged figures ofNike. Later the famous parapetwith its relief Nikai was addedaround the edge of the precinct.

SIGNIFICANCE

Noteworthy at the least for beingone of the four main new build-ings of the Periklean Acropolisproject; though the smallest, anditself copied from the temple onthe Ilissos, its designs were inturn later copied on the greatErechtheion. Elsewhere on theAcropolis we see the Doric orderbeing modified in the direction ofthe Ionic, with slenderer columns

and decorative mouldings; theNike temple shows the samething in reverse, with the Ionicorder being made to look stockierand closer to the Doric. This isnot necessarily a deliberate poli-cy, as we can understand the rea-sons why it happened in eachcase (in this case as a conse-quence of having to build on areduced site and fit in with anarchitectural environment domi-nated by the massive proportionsof Doric), but it certainly fore-shadows the convergence of theorders that followed later, andmay well have been influential inbringing this about. The way inwhich the plan was altered is atribute to the ingenuity and flexi-bility of the unknown architectwho actually built the temple.Finally, it is worth pointing outthat the subject-matter of thefrieze is, exceptionally, historicalrather than mythological, andpoints towards the theme of thevictory over the Persians thatreappears in allegorical form onthe Parthenon. (The Battle ofPlataia was the final, decisiveland-battle of the Second PersianWar, the year after Salamis, inwhich the Spartans, not theAthenians, played the most effec-tive part.)

DATE: c. 427-424 BC ORDER: IONIC

18. Athens: Athene Nike

19. Corner capital, temple of AtheneNike

-

17

BACKGROUND

The Propylaia (a plural noun,gateway complex) replaced theearlier Propylon or gatewaywhich had dated from the time ofthe Older Parthenon. This build-ing had also been ravaged by thePersians but, being secular, hadnot been covered by the oath ofPlataia and had apparently beenrebuilt. It had been a large squarebuilding, possibly faced front andrear by four columns in-antis, anddivided in two by a gate-wall. Ithad faced strongly towards thenorthern edge of the acropolis.

The new design by Mnesiklesstarts with the orientation of thebuilding, which is rotated to faceeast instead of north-east. It thusfaces directly towards the spotwhere the great bronze statue ofAthene Promachos by Pheidiasstood. It was built entirely ofPentelic marble, with the addi-tional use of blue-blackEleusinian limestone for poly-chrome effects (as dado beltcourses for walls etc.). The build-ing was left unfinished at the out-break of the Peloponnesian Warand never completed.

DESCRIPTION

Central Gate

The central part of the buildingserved the same function as itspredecessor and was designedaccordingly, with porches at eachside and a dividing wall piercedby five gates. This time theporches were hexastyle; the slope

in the ground meant that therewould be a difference of 5' 9" intheir heights, and it was clearlythought that though a split-levelbuilding was feasible, the jump inthe roof-line would be ugly; sothey tried to minimise the differ-ence by two means: firstly thewest porch stood on a stereobateof four steps, the eastern on asimple stylobate; secondly,though the columns are all of auniform diameter, those of theeastern faade are nearly a footshorter. (The effect is designed tobe less noticeable by virtue of thefact that the west columns arealways seen from below, and soforeshortened.)

The central intercolumniation wasmade wider, to accommodate therichly equipped festival proces-sions with their carriages and sac-rificial animals; normal accesswould have been through theside-entrances. (The effect of thisis seen on the metope frieze,which has three metopes between

the central columns instead of theusual two.) A great ramp 12 feetwide rises through the centre, cut-ting through the floors of thebuilding. Accordingly there is noupward curvature of the stylobate,but the entablatures are upcurvedas if there were.

The gate-wall with its five gradu-ated openings divided the interiorinto two unequal halves, beingcloser to the east (inner) porch.This meant that the roof could bespanned by a marble ceiling with-out intermediate supports, andadditionally gave greater space tothe west porch, with the advan-tage that pilgrims could gatherthere and wait on the benchesprovided for the gate to beopened. This deep western porchneeded supports for its marbleceiling; single Doric columnswould have been too bulky, and atwo-tired colonnade would havehad no logical way of terminatingits intermediate architrave againstthe open west portico.

DATE: 437-432 BC ORDER: DORIC

20. Athens, Propylaia, as proposed (light lines) and as built. The original Propylon isshown in outline at a slant

- Accordingly Ionic columns wereused, exploiting their extra height(nearly 10 lower diameters, cf.the

-

19

BACKGROUND

The Erechtheion was intended toreplace the older Peisistratid tem-ple of Athene Polias which hadbeen mostly destroyed by thePersians; the surviving part, theopisthodomos, was re-roofed andconverted into the State Treasury,while the sacred olive-woodxoanon was housed in a tempo-rary shrine slightly to the north.Hence the need to move the siteof the temple from the ideal spotoccupied by its predecessor to afar more inconvenient positionnearer the north edge of theAcropolis, where the rockslopes away awkwardly.This had not been a prob-lem for the Parthenon,where the land was ter-raced up to make a greatlevel platform; howeverhere the architects choseto live with the problemand designed a split-level,asymmetric building.

Work on the temple wasinterrupted several timesby the PeloponnesianWar. A complete set ofaccounts covering alldetails of expenditure onmaterials, transport,wages, and contractorswas found built into the precinctwall. Progress was clearlydependent on there being suffi-cient funds to pay for it, and themilitary emergency made it nec-essary to count the cost very care-fully.

The architects were Mnesikles(who also designed the

Propylaia), and possiblyKallimachos, who designed thegolden palm-tree lamp inside(and is also credited with theinvention of the Corinthian capi-tal).

DESCRIPTION

Layout

The old temple had been peripter-al Doric with strong Ionic fea-tures, with a complex internalorganisation reflecting the manydifferent cults that it housed. Theintention was clearly to re-house

all these cults within a singlereplacement building, but the newsite meant a peripteral temple wasout of the question. Possibly theoriginal intention was to have asanctuary fronted east and westby prostyle porticoes; that at theeast end was retained, but thewest end encroached too fartowards the Pandroseion (olive-

tree precinct) and the tomb ofKekrops, so that the west porticois represented only by fourengaged columns between theantae of the west wall, with(Roman?) windows in the threeintervening positions. Belowthese columns is a high basementwall, pierced by a doorway,which overlooks the Pandroseion.

The west portico is effectivelyreplaced by a north porch of sixcolumns, four wide, which over-laps the north-west corner of thecella. There was a central northdoor which gave access to thewestern half of the interior; at the

point where theporch exceeded thecella another doorled to a staircasedown to thePandroseion and thewest, basement,door. Underneath thenorth porch a subter-ranean east doorconnected the cryptbelow the porch to asnake pit under thefloor of the interior.The crypt floorshowed the marksof Poseidons tri-dent, a holy spotwhich had to beexposed to the sky,

requiring the floor and the ceilingof the north porch immediatelyabove to be pierced with shafts.

The south porch was designed asa balance to the north; it has thesame arrangement of columns,four wide with two returns,though it is much smaller and thecolumns are replaced by cary-

DATE: c. 421-405 BC ORDER: IONIC

21. Erechtheion, asbegun and as finished

-

atids. The caryatids are slightlyirregularly placed and the dimen-sions of the porch appear to havebeen squeezed, suggesting that amoment came during buildingwhen it was realised that therevised building plan would stillpush the west wall over the tombof Kekrops and would have to bepulled back a further 26". Thereis a floor-level entrance on theeast side of the caryatid porch andan L-shaped staircase leadingdown to the interior. Notice thearrangement of the figures, espe-cially the way the three westernfigures have their weight leg tothe west (and the eastern ones tothe east), presenting the viewerwith the unbroken column-likefolds from whichever side he seesit. Above this porch was a flatmarble roof which, it has beensuggested, may have been appro-priated for a ritual or ceremonialpurpose connected with thearrephoroi, whom the caryatidsmay be intended to represent.Perhaps the chief priest displayedthe new robe to the people fromthere.

The inner arrangement of therooms is controversial. The interi-or was clearly divided laterally intwo by a great cross-wall, withthe floor of the two halves at dif-ferent levels. Entrance to thehigher east room, dedicated toAthene and Erechtheus, was thenthrough the east porch. The otherrooms were presumably reachedvia the north porch, which gavefirst onto the west room, probablyan ante-chamber of sorts, with thecisterns of Poseidons springbelow the floor and additionaldoors to the west and south; thisis turn led to the two centralrooms. Here the cults of Botesand Hephaistos were located. Thewest and central rooms were sep-arated by walls which were only

12' 10!/2" high and so did notreach all the way to the ceiling,which was common to all threerooms.

Materials and decoration

Pentelic marble was usedthroughout except for the blue-black Eleusinian limestone usedin the frieze. Different sets ofproportions are used for each ofthe main parts of the temple: theeast front (hexastyle because thecolumns are shorter but the widthof the porch is the same as the tallnorth porch) has intercolumnia-tions of barely more than twodiameters, whereas in thetetrastyle north porch the columnsare nearly three diameters apart.

Throughout the temple, the levelof decorative detail is exception-al; everywhere one finds mould-ings not just painted but carved aswell. The Ionic bases of the twomain porches are different: theeast ones have a horizontally flut-ed upper torus, those of the northtwo guilloche designs instead.Extremely rich column capitalsboast compound spiral ribs withintermediate fillets in the volutes,and a countersunk gilt bronzestem between the convolutionsending in a group of petalsspreading out to fill the triangulargaps. The eyes of the voluteswere also gilded; above the egg-and-dart echinus was a torus inguilloche, the interstices of whichin the north porch were filledwith glass beads of four differentcolours. There are necking bandslike collars, carved withanthemion, with a beaded astragalbelow at the east end. The antacapitals are also exceptionallyrich, with a heart-and-dart cyma(wave) moulding above an egg-

and-dart ovolo separated by lay-ers of beaded astragal, and thisdesign is carried around thewhole building as a decorativeband.

The caryatid maidens supportcapitals reminiscent of the laterRoman Doric, an echinus carvedwith egg-and-dart.

Following the precedent of theNike temple, the architrave hasthree fasciae, and a cyma mould-ing above replaces dentils. Abovethe caryatid porch there is nofrieze, but the upper fascia of thearchitrave was prepared toreceive rosettes; curiously, thesewere never finished, and onlydiscs are seen. Dentils were alsofurnished for the cornice.Doorways (and, a rare feature,windows) had a mass of decora-tive detail applied to their frames;consoles are seen supporting thelintel of the east door. The porchceilings were coffered in marble,the inner ones in wood; the deepnorth porch coffers had bronzerosettes suspended from theirvaults, while those of the westinterior had wooden rosettes oftwo designs.

SIGNIFICANCE

Small, lavishly decorated inaccordance with its deep sanctity,and irregular in plan. Very inter-esting for the light it sheds on theprocess of temple designbasi-cally worked out as the buildingprogressed, normally according tosome carefully worked out rulesof thumb, but here clearly run-ning into difficulties which neces-sitated alterations to the designeven while the work was pro-ceeding. The temple hence cannotclaim to be an ideal of any typesince it is so eccentric, but itsdetails were widely copied.20

-

21

DESCRIPTION

This temple in Asia Minor wasdedicated by Alexander the Greatin 334 B.C. The plan of the archi-tect, Pythios (who also designedthe Mausoleum at Halikarnassos)consisted of a peristyle 11 6columns enclosing a pronaos andopisthodomos, and the propor-tions seem to embody an attemptat a canon: the axes of the colon-nade form a rectangle 120 60Ionic feet and the axial spacing is12 Ionic feet; the length of thecella building is 100 Ionic feet,while the interior length of thecella is 50, and so on. The Ioniccolumns of the peristyle are justunder nine lower diameters highand rest on square plinths (thisfeature only known otherwise atEphesus) which are six feet wideand six feet apart.

The design overall is very tradi-tional Ionic: there is no friezebecause dentils are present (onlyone or the other is usual on anIonic temple); the column basesare of the Asiatic type (i.e. a hori-zontally fluted torus above acomplex spira); there is the usualnumber of flutes (24) separatedby fillets; the capitals retain thesagging line between the volutes,characteristic of the best period,and show the egg-and-dart echi-nus above a beaded astragal. Theangle capitals have one continu-ous, though rather contracted,volute on the internal corner, asopposed to the usual intersectingones, and the outer corners have apalmette carved below the cantedvolute.

Moving upwards from the capital,each layer projects outwards fur-ther than the one below: after theabacus, its sides in a wave mould-ing ornamented with a leaf pat-

tern, come the three successivefasciae of the architrave; next anastragal below an egg-and-dartovolo, with the dentils above; anda further astragal and ovolotopped by the plain face of thecornice, crowned with a smallmoulding, and finished by thegutter, which itself was ornatelydecorated with a series of rainwa-ter spouts in the form of lionheads, between extravagant dis-plays based on palmettes andacanthus leaves. The placing ofthe water-spouts is interesting asthey are grouped in threes, oneover the centre of each interco-lumniation and one over each ofthe eyes of the volute; and thetheme of triplets is seen again inthe fasciae of the architrave, andthe groups of decoration above.Even the cornice itself has threelayers.

SIGNIFICANCE

Priene was a rather small templebut considered exquisitely beauti-ful, presumably for its delicatebut well-balanced proportions andfinely detailed decoration. It is an

excellent example to give of theideal of Ionic architecture; never-theless, odd details do stick outas unusual, and this together withthe late date illustrate the fact thatIonic never really reached thesame degree of rigidity as a deco-rative scheme that Doricachieved.

To see it, you might have had theimpression of a very slight entab-lature carried on tall columns(certainly a striking contrast withe.g. the Athenian Hephaisteion);however one must give the archi-tect credit for knowing his ownbusiness, especially as the propor-tions elsewhere are so carefullyworked out. Clearly he wished toavoid any impression that thecolumns were over-loaded, andthe result was surely a light,graceful and elegant building.

Note the way the stereobate ismade up of a regular grid of stonesquares, with the columns occu-pying the centre of those alongthe outside. There is no sugges-tion of widening or narrowingcolumns or intercolumniations forany reason at all. This supremelyrational approach is in sharp con-trast to the Doric method, whichhad to work out the number ofcolumns, their widths and spac-ings, according to whatevermethod was being used to dealwith the triglyph problem, andthen calculate the dimensions ofthe stylobate from that. This givesDoric temples the virtue of organ-ic wholeness as works of art, butIonic the practicality of being aserviceable decorative schemewhich can be simply reproducedad infinitum.

DATE: c. 340-334 BC ORDER: IONIC

22. Temple of Athene Polias, Priene

-

22

DESCRIPTION

This temple, designed byTheodotos, lacks anopisthodomos; the cella finishesin a blank wall in line with thepenultimate columns, and the rearpteroma is reduced to the samewidth as on the flanks. The col-umn plan is accordingly reducedto 11 6; the entrance to the cellais in line with the third column.The interior of the cella containeda colonnade which can scarcelyhave served any structural pur-pose (as the temple is quite small)so must have been decorative. Ithas not survived, but the patternin other, later, buildings atEpidauros of using Corinthiancolumns internally suggests thattreatment began here.

The expense accounts for thistemple survive. The east pedi-ment contained sculptures depict-ing Greeks fighting Amazons, thewest the capture of Troy. In thecella stood a chryselephantinefigure of Asklepios.

SIGNIFICANCE

Fourth century architects workingwith the Doric order still appar-ently feel impelled to develop itfurther, despite a sort of perfec-tion having been reached the cen-tury before. Here the amputationof the opisthodomos has beencarried out without any attempt tocounteract the effect on the over-all proportions of the building,which may well have lookedrather stumpy as a result. At anyrate, the design was not repeatedin subsequent buildings, so may

have been regarded as a failure.

The internal colonnade may becompared with others such asBassai or the AthenianHephaisteion which were addedpurely for effect. The form oftemples was originally governedby their structure : for instance,internal colonnades being intro-duced to support the roofs in larg-er, wider buildings; or one mightmention the origins of the Doricorder itself in the functionalforms of a wooden type of archi-tecture. Later there is a tendencyto divorce form and structure: thetriglyph frieze appears too low onthe exterior to approximate itssupposed function of capping theceiling beams, and internal colon-nades appear which have a purelydecorative function.

OTHER TEMPLES ATEPIDAUROS

Three other temples at Epidaurosshould be mentioned. Firstly, ded-icated to Artemis, a small temple,only 27' wide, consisting of justcella and pronaos, but decoratedas lavishly as any large temple. Ithas a hexastyle prostyle front inthe Doric order (a lot of columns

in a narrow space!), with a pavedwalk and ramp connecting it tothe altar; acroteria in the form ofNikai; internally there is aCorinthian colonnade close to thewalls, so functionally redundant.A nice touch is the provision ofwater-spouts in the form of hunt-ing-dogs (Artemis was goddess ofhunting) instead of the usual lion-heads.

Two other small temples havebeen identified, possibly ofAphrodite and Themis. These hadIonic columns lining the cella onthree sides.

DATE: c. 370 BC ORDER: DORIC

23. Temple of Asclepios, Epidauros

-

23

DESCRIPTION

The earliest of the three notablefourth-century tholoi; it stood inthe precinct of Athene Pronaia(otherwise known as theMarmaria) somewhat distant fromthe main sanctuary of Apollo, andthree of its peristyle columnstogether with a correspondingsegment of the entablature havebeen re-erected on the site. It wasprobably designed by Theodorosof Phokaia, whose book about thebuilding was quoted by Vitruvius.

The building has a circular cellasurrounded by an external peri-style of 20 Doric columns stand-ing upon a stylobate less than 49'across and three feet high. Thesmallness of the buildingandtherefore also its pronounced cur-vaturemeans that the externalcolumns are rather closer togetherthan they would be on a contem-porary rectangular building. Thenumber of internal columns isrelated to the number on the out-side; but ten standing in such arestricted space (less one for thedoorway) would have been asevere inconvenience, so they areraised up onto a black limestonebench which encircles the interi-or. The floor is made of the samestone, except for a white marblecircle in the centre; the exteriorwall of the cella also had a blackbase.

The internal columns were of theCorinthian order. They stoodagainst the interior wall withoutactually being engaged to it. Theyhad 20 flutes, and capitals thatrecall those at Bassai, with two

rows of very smallleaves girdling thebase (in fact, theseleaves vary fromone column to thenext); here, howev-er, the bases of thespringing volutesare not masked bythe leaves, but forma lower spiral, cre-ating S-shapeswhich meet in akind of lyre pattern.

This tholos is to bereconstructed withtwo roofs: oneraised up on thedrum of the cellawall (which mayhave been piercedwith windows above), and anoth-er roof over the pteron slopingdown from a lower point on thewall. The gutter of the Doricentablature was richly ornament-ed and carried lion-head waterspouts. The metopes were allcarved with figures.

SIGNIFICANCE

An early experiment in applyingthe architectural scheme workedout for rectangular buildings to acircular plan. The tholos inAthens shows that there wereround buildings before, but itdoes not have the external Doriccolonnade. Later tholoi atEpidauros and Olympia take theidea further.

The purpose of the building is notknown.

DATE: c. 375 BC ORDER: DORIC

24. Tholos at Delphi: section

-

24

DESCRIPTION

Designed by Polykleitos theYounger, who also designed thetheatre here. The accounts surviveand show that building took overthirty years, proceeding as fundsbecame available. The mainbuilding material, presumably forcheapness' sake, was limestone,except where precision of carvingnecessitated marble. The buildingconsists of a circular cella, sur-rounded by a peristyle of 26Doric columns, resting upon astylobate just over 66' across. Thethree-stepped base is interruptedby an approach ramp. The entab-lature, in accordance with thefourth-century style, isslight, with a shallowarchitrave and cornice,though the frieze has itsfull emphasis, and themetopes are for the firsttime carved withrosettes in relief. Thegutter is elaboratelycarved with lion-headrain-water spouts inbetween a patternderived, like that of theCorinthian capital, fromthe acanthus plant; pal-mette antefixes appearabove, their leaves curlyrather than straight,again owing to the influence ofthe acanthus pattern.

The interior was lit by two win-dows either side of the doorway,showing off the elaborate floorwith its pattern of alternatingblack and white rhomboidal slabs,and the internal order of fourteenCorinthian columns, detached

from the wall, and with fine capi-tals which are virtually indistin-guishable from the version ofCorinthian which eventuallycame to predominate as the stan-dard: note the flower overlappingthe mid-point of each side of theabacus, and the delicacy of theacanthus ornament, the thinnessand naturalism of which are insharp contrast to the plainness ofthe stone bell; the stems of thevolutes too are carved free of thebackground. This fine ornamenta-tion was too fragile to survive thecollapse of the building, but luck-ily an unfinished and unused cap-ital of identical appearance wasfound buried nearby; it might

have been a template for the orig-inal masons to copy. Above, thereis an elaborately carved entabla-ture, with the Corinthian friezeshowing a wave moulding (anearly example of a feature thatwould be regularly seen later).The ceiling coffers again are veryrich, with ovolo and astragal bor-

ders, carved flowers set into thevaults, and acanthus ornaments inthe triangular interstices betweenthe coffers. A single conical roofrose from the outer entablatureand culminated in a great floralacroterion.

At the centre of the floor a recessled down to a crypt which con-sisted of a series of concentricwalls forming corridors connect-ed by doorways: a sort of under-ground labyrinth or maze, per-haps connected with the snake-cult of Asklepios, in which case itwould be comparable to thesnake-pit under the Erechtheion.

SIGNIFICANCE

The most splendid andbeautiful of tholoiaccording to the verdictof antiquity. It shows usthe version of theCorinthian capital thatcomes to be the norm inlater years, and con-tributes further to thedevelopment of aCorinthian order with thecyma (wave) mouldingon the frieze.

Unfortunately this build-ing does not help us with

the purpose of the tholos as anarchitectural type, since we donot know what it was for. It mayhave been a temple connectedwith the cult of Asklepios, oreven a repository for his bones.

DATE: begun c. 360 BC ORDER: DORIC

25 Tholos at Epidauros

-

25

DESCRIPTION

This is a tholos or round building,begun by Philip of Macedon as amonument to his victory atChaironea, and completed by hisson Alexander; it housed chryse-lephantine statues by Leocharesof Philip, Alexander, Amyntas,Olympias and Eurydice. It con-sists of a circular cella surround-ed by an Ionic colonnade of 18columns resting on a three-stepped stereobate. The singleconical roof (not as shown in thereconstruction) was topped by abronze finial in the form of apoppy-head, which hid the endsof the roof beams.

The details of the Ionic order areunusual: the base has a torusabove a scotia, resting directlyupon a plinth (i.e. like the Atticbase but lacking the larger lowertorus); there are 22 flutes insteadof the normal 24; the capitals lack

the egg-and-dart ovolo. Probablyfor the first time the Asiatic den-tils appear together with themainland frieze (cf. e.g. Priene), apractice which was to becomenormal in later times.

The interior was lit by two win-dows either side of the door. NineCorinthian half-columns wereengaged to the inner wall of thecellahalf the number of theexterior columns. As atEpidauros, the internal colonnademust be seen as purely decora-tive; here, however, enough sur-vives for the design of theCorinthian capitals to bedescribed. Each of the fourvolutes emerges from a flutedsheath called the cauliculus (aform taken from the natural formof the acanthus plant); there areno subsidiary spirals meeting onthe intervening faces, but acan-thus leaves instead, and a girdleof small leaves around the bare

upper part of the bell, as atBassai.

SIGNIFICANCE

A further illustration of the fluidi-ty of the Ionic order; theCorinthian too is unusual, show-ing that it has not yet reached thefinal form seen in the tholos atEpidauros. Form and structure areagain separate. There is carefulharmony of proportions (e.g. withthe numbers of columns); the useof frieze in conjunction with den-tils proved influential.

DATE: begun 339 BC ORDER: IONIC

26 Olympia: Philippeion. Hypothetical reconstruction

-

26

THE STOA

In general the primary function ofa stoa was to provide shelter fromwind and rain. Gathered in smallgroups up and down the length ofthe colonnade, people could meetand hold discussions in private,despite the lack of partitions; thusit became customary to use stoasfor business purposes, and even-tually they were designed accord-ingly, with their interiors dividedinto units suitable for stalls, shopsand offices. Partition walls pro-jected from the rear wall towardsthe open front of the colonnade.This in turn required greaterdepth, so a ridged roof was pro-vided, needing intermediate sup-port, which was provided eitherby the wall across the front of thepartitions, or an internal colon-nade. Since Doric was usual forthe exterior columns and theinternal range would have toreach higher, the Ionic order wasused inside to save space. Bothorders were architectural schemesthat had been worked out for useon temples, and were now appliedsystematically to a secular type ofbuilding of a very different shape.It soon became clear that thiswould result in further modifica-tions to the orders, especially theDoric.

PURPOSE

The Stoa Basileios (or RoyalStoa) probably dates originallyfrom the Archaic period, towardsthe end of the sixth century B.C.,but after suffering damage in thePersian sack of 480 B.C. was

extensively rebuilt in the fifthcentury. The building takes itsname from its purpose as theheadquarters of the ArchonBasileus (or King Archon), a sen-ior Athenian magistrate with par-ticular responsibility for religiousaffairs and certain types of law-suit; Sokrates says in PlatosApology that he had to reporthere in the first instance toanswer the charges that had beenbrought against him, which even-tually led to his execution.

These functions of the KingArchon are reflected in the fur-nishings of the building itself: forexample, the base of a herm wasfound which was apparently setup in about 400 B.C. to com-memorate the archonship of oneOnesippos, and it records thenames of the winners of thatyear's Lenaia. As the dramaticfestivals were sacred to Dionysos,they fell within the jurisdiction ofthe King Archon. Immediately infront of the building there was along slab of unworked limestoneapproximately 3' 9' whichappears to have been the OathStone used ceremonially by newmagistrates to swear to upholdthe laws; being ancient it predatesthe stoa and may have dictated itsposition. Towards the end of thefifth century, the Athenian law-code was inscribed on slabs ofstone and set up in this stoa sothat it could be consulted by anycitizen. Also connected with theKing Archon and his two assis-tants are the sets of thrones whichoriginally stood either inside orjust in front of the stoa.

According to a line inAristophanes, official dining tookplace here as well as in the tho-los. This has been proven correctby the find of a large deposit ofcooking ware, animal bones andred-figured wine-cups and kratersfrom the mid-fifth century.

DESCRIPTION

This early stoa was very small incomparison with later examples,just 58' 23', with only eightDoric columns between the endwalls, and an interior supportedby four (originally two?)columns, likewise in the Doricorder. The frontage therefore iscomparable with the scale of atemple, and the proportions anddetails of the order are similar,with two-metope spans betweenthe columns. Small wings wereapparently added at either endtowards the end of the fourth cen-tury to display the law-code;these each had a three columnwidth, with a column behind eachof the two corners.

SIGNIFICANCE

Important as an early example ofa stoa, showing that such build-ings had been in use since at leastthe sixth century. The interior isnot partitioned, but supportedwith Doric columns. The Dorictemple scheme is applied to thisbuilding without modification.

DATE: 575-500 BC (rebuilding) ORDER: DORIC

-

27

27. Stoa Basileios, restored elevation, first period

28. Stoa Basileios, restored elevation, in about 300 B.C., showing the addition of wings at either end, built partly to display theinscribed law code. In front is the monumental statue of Themis, goddess of justice, erected in about 330 B.C.

29. Stoa Basileios, sixth century B. C.: (a) hypothetical section, (b) part elevation

-

28

DESCRIPTION

This stoa was designed from thestart to have two projections ateither end, enframing a recess,with a statue of Zeus at the cen-tral focal point. The externalDoric colonnade consisted of ninecolumns along the recess, spacedmore widely than those of thewings, which were six columnswide and four deep (countingthose at the corners twice). Thewider spacings of the centralrecess were catered for by placingthree metopes to each span inplace of the usual two (a lessonlearnt from the central doorwayof the Propylaia). The interiorwas supported by a row of sevenIoniccolumns,with onemore at eachend in linewith the pro-jecting wing.The roof wasgabled overeither wing;there wereacroteria butno pedimentsculptures.

Unlike mostof the build-ings in the

Agora, the faade was builtentirely of Pentelic marble. Thismay be explained by the nature ofthe building itself: being dedicat-ed to Zeus, it was a religiousbuilding though in the guise of asecular one. Eleutherios meansthe Liberator; the cult of ZeusEleutherios had been founded inthe wake of the Persian Wars, tocelebrate the winning of freedomfrom the threat of Persian domi-nation, and maintained by theAthenians, who adorned thebuilding with the shields of thosewho died fighting for the city.

Like other buildings, the Stoa ofZeus was adorned inside withpainted panels.

SIGNIFICANCE

Though a stoa, the fine marblebuilding stone, hexastyle wingsand acroteria underline the reli-gious nature of the building andits corresponding prestige. Note,however, the modifications to theDoric order: the widening of thecentral intercolumniations can beexplained in terms of improvingaccessibility and the need tolighten the effect of a long colon-nade. The Ionic appears inside asa logical solution to the problemof the internal colonnade; boththis and the use of three-metopespans are ideas derived from thePropylaia.

DATE: 430-420 BC ORDER: DORIC

30. Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios: reconstructed elevation

31. Stoa Poikile, reconstructed perspective view

-

29

DESCRIPTION

This was one of the most well-known buildings of ancientAthens; its fame derived from thelarge, movable wooden panelshung along the rear wall whichwere painted by the celebratedartists Polygnotos, Mikon andPanainos. (The name Stoa Poikilemeans Painted Stoa.) Thesepaintings excited a great deal ofadmiration in the ancient world,but have disappeared withouttrace. Apparently they were stillin place some 600 years after theywere created, as Pausaniasdescribed them in his guidebook;all depicted scenes of Athenianand Greek military exploits, suchas the Trojan War, Athenians andAmazons, etc. The most celebrat-ed painting showed the Athenianvictory at Marathon.

The site of the stoa remainedentirely unknown until someexcavations in 1981 revealedsome likely ruins, which stillunfortunately are not fullyexposed since much of the build-ing lies beneath modern houses.The width has been established as12.5 metres; if the proportionsnormal for a stoa were observed,the length would have been atleast 36 metres, possibly more.The external order was a severeDoric; internally the Ionic orderwas used to support the highridge beam while taking up theminimum of floor space. Much ofthe stoa was built of various typesof limestone, though the Ioniccapitals were carved from marble.

For a secular building, the stan-

dard of workmanship and materi-als is high. For example, the step-blocks were all cut to the samelength and fastened with double-T clamps, set in lead, and withalternate joints coinciding exactlywith the centre of each column;this is a degree of precision oneexpects to see in high-prestigeprojects such as temples, butwhich is rare in secular buildings.

The location of the stoa is ideal,bordering the north side of theAgora and looking directly alongthe Panathenaic Way towards theacropolis; in winter it will havemade a perfect place to gather,sheltered from the cold northwind, its open south side makingthe most of the weak winter sun-shine.

As well as the paintings, the stoaalso contained other reminders ofpast Athenian victories. Bronzeshields from defeated enemieswere exhibited here, includingthose from the 292 Spartans whowere captured alive at Sphakteria,near Pylos, in 425-4 B.C., one ofAthens most noteworthy victo-ries in the Peloponnesian War.One such shield, roughly punchedwith the words The Atheniansfrom the Lakedaimonians atPylos, has survived, and is to beseen in the Agora museum in therebuilt Stoa of Attalos.

Besides displaying paintings andtrophies, the stoa had a variety ofother functions. It is unusual innot, apparently, having been pro-vided for any specific use or forthe benefit of a particular groupof officials; rather it was a public

amenity, serving the needs of thepeople at large, as a shelter andmeeting-place just off the Agora.It could be used as a law-court;official proclamations were alsomade here; but in the main it wasan informal place of assembly forall and sundry. This is made clearby many written sources whichmention the frequent use of thestoa by those who depended oncrowds to make their living:sword-swallowers, jugglers, beg-gars, scroungers and fish-mon-gers. Most famously it was thephilosophers who gathered here,using the stoa as a classroom; oneschool, founded by Zeno, is par-ticularly associated with the StoaPoikile, and even took its namefrom it: the Stoics. One has theimpression of a lively meeting-place where the Athenians cametogether to converse, argue, andlearn.

SIGNIFICANCE

Note the early use of an Ionicorder internally; the careful loca-tion to take advantage of the shel-ter; the lavish construction; itsrole as a popular amenity. Thereconstruction by Dinsmoor Jnr.shows the external Doric orderwith the two-metope spans typi-cal of early stoas, having not yetdeveloped the distinctive Doricwith three or more metope spanswhich characterised later stoas.

DATE: 475-450 BC ORDER: DORIC

-

30

NAME

The original name of this build-ing is not known. The name givento it by archaeologists denotes itsposition along the south side ofthe Agora, and distinguishes itfrom the later South Stoa IIwhich replaced it in theHellenistic period.

DESCRIPTION