Granulomatous Lung Desease

-

Upload

luca-viviano -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

0

Transcript of Granulomatous Lung Desease

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

1/24

Granulomatous Lung DiseaseAn Approach to the Differential Diagnosis

Sanjay Mukhopadhyay, MD; Anthony A. Gal, MD

N Context.Granulomas are among the most commonlyencountered abnormalities in pulmonary pathology andoften pose a diagnostic challenge. Although most pathol-ogists are aware of the need to exclude an infection in thissetting, there is less familiarity with the specific histologicfeatures that aid in the differential diagnosis.

Objective.To review the differential diagnosis, suggest apractical diagnostic approach, and emphasize major diagnos-ticallyusefulhistologicfeatures.Thisreviewisaimedatsurgicalpathologists who encounter granulomas in lung specimens.

Data Sources.Pertinent recent and classic peer-reviewed literature retrieved from PubMed (US National

Library of Medicine) and primary material from theinstitutions of both authors.

Conclusions.Most granulomas in the lung are causedby mycobacterial or fungal infection. The diagnosisrequires familiarity with the tissue reaction as well aswith the morphologic features of the organisms, including

appropriate interpretation of special stains. The majornoninfectious causes of granulomatous lung disease aresarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, hypersensitivitypneumonitis, hot tub lung, aspiration pneumonia, andtalc granulomatosis.

(Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:667690)

The most common sites where surgical pathologistsencounter granulomas are the skin and subcutaneoustissues, lymph nodes, and lungs.1 Most pathologistsrespond appropriately to this finding by ordering specialstains to exclude an infection. However, the process ofdetecting and identifying an organism frequently proves

quite challenging. Most pathologists dread interpretingthe special stains, namely, Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) and Grocottmethenamine silver (GMS). The task is even more arduousif, as is commonly the case, an organism is not detected.The lack of identifiable organisms in tissues raisesquestions about the next appropriate step for thepathologist to pursue. Does one dust off a lung pathologytextbook, seek extramural consultation, or merely issue adescriptive diagnosis? What other diagnoses should beconsidered? Do the black particles on the GMS stainrepresent fungi? If the results obtained with special stainsare negative, is the diagnosis sarcoidosis or could it beanything else? These are some of the problems that plaguesurgical pathologists on a daily basis.

The following review attempts to address these issuesand will hopefully ease the task of approaching thedifferential diagnosis of granulomatous lung diseases.Since clinical and radiographic information is oftenunavailable to pathologists at the time of diagnosis, our

emphasis will be on the histologic features. The reader isalso referred to other excellent reviews on the subject. 24

DEFINITION AND TERMINOLOGY

A granuloma is a compact aggregate of histiocytes(macrophages).5 The histiocytes in granulomas are often

described as epithelioid. Epithelioid histiocytes haveindistinct cell borders and elongated, sole-shaped nuclei,as opposed to the well-defined cell borders and round,oval, or kidney beanshaped nuclei of ordinary histio-cytes. Aggregation of histiocytes is the minimum require-ment of a granuloma, regardless of whether the lesion alsocontains necrosis, lymphocytes, plasma cells, or multinu-cleated giant cells.

APPROACH TO THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OFGRANULOMATOUS LUNG DISEASE

The differential diagnosis of granulomatous lung diseaseis listed in Table 1. The following is our recommendedstep-by-step approach to pulmonary granulomas.

Step 1: Attempt to identify an organism.Step 2: Look for histologic features of noninfectious

granulomatous diseases (Table 2).Step 3: If steps 1 and 2 do not yield a specific diagnosis,

ensure that an adequate number of blocks have beenstained with special stains and reexamine the specialstains. If no organisms are found despite a thoroughreexamination, issue a descriptive diagnosis including thetype of granulomas (necrotizing, nonnecrotizing, or both)and the absence of identifiable organisms. Suggest adifferential diagnosis in a comment.

Step 1: Identifying Organisms

Since infection is the most common cause of pulmonarygranulomas, it is always important to carefully exclude an

Accepted for publication April 16, 2009.From the Department of Pathology, State University of New York

Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York (Dr Mukhopadhyay);and the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, EmoryUniversity School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia (Dr Gal).

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products orcompanies described in this article.

Reprints: Sanjay Mukhopadhyay, MD, Department of Pathology,

State University of New York Upstate Medical University, 750 EastAdams Street, Syracuse, NY 13210 (e-mail: [email protected]).

Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal 667

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

2/24

infectious etiology before diagnosing a noninfectiousgranulomatous lung disease.

Organisms in Pulmonary Granulomas: What toExpect.The organisms most commonly found in gran-ulomas of the lung are mycobacteria and fungi.1 Mycobac-terium tuberculosis is common in the developing world,while nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are frequentlycultured from granulomas in the United States. The mostcommon fungal causes of pulmonary granulomas are

Histoplasma, Cryptococcus, Coccidioides, and Blastomyces.Prevalence of these fungi varies by geographic region. Inthe United States, Histoplasma is primarily seen in thecentral and eastern states, Coccidioides is endemic in theSouthwest, Cryptococcus is ubiquitous, and Blastomyces is

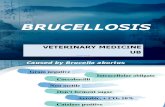

infrequent.68 Aspergillus rarely causes granulomatouslung disease. Other fungi (Chrysosporium and Sporothrix)and bacteria (Brucella and Burkholderia) may also rarelycause granulomatous lung disease.

Using the Tissue Reaction as a Clue.Organisms mustbe sought in both necrotizing and nonnecrotizing granu-lomas since they may be found in either type.2,9 However,the search must be especially thorough in necrotizing

granulomas since these are more likely to yield anorganism.1,7,9,10 Other features of the tissue reaction oftenprovide a clue to the type of organism present. Forexample, the presence of neutrophils in granulomas shouldprompt a search for Blastomyces, while the association ofeosinophils with granulomas often indicates the presenceof Coccidioides. Infarctlike necrosis may be seen ingranulomas caused by Histoplasma or M tuberculosis, whilea bubbly appearance of the cytoplasm of histiocytes andmultinucleated giant cells is a clue to the presence ofCryptococcus. Despite these helpful associations, there isenough histologic overlap in tissue reactions that no onefeature is absolutely specific for a particular organism.

Examining Special Stains for Organisms.The search

for organisms must always begin with hematoxylin-eosin(H&E)stained sections. Many pathologists, incorrectlyassuming that organisms will not be visible on H&E, skipthis vital step and go directly to the special stains.Although this is true for mycobacteria, most fungi arereadily identified on careful examination of an H&E stain.Examination of H&E-stained sections also enables thepathologist to discern subtle differences in morphologybetween organisms and place the organism in the contextof the associated tissue reaction. The notable exception tothis general rule is Histoplasma, which is virtuallyimpossible to detect within necrotizing granulomas onH&E-stained sections.1013

The histochemical stains used most often for identifica-tion of organisms are GMS for fungi and ZN (oftencolloquially called AFB for acid-fast bacteria) formycobacteria. Although some laboratories additionallyperform a periodic acidSchiff stain for fungi, the GMS

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of GranulomatousLung Disease

Infections

MycobacteriaMycobacterium tuberculosisNontuberculous mycobacteria

FungiHistoplasmaCryptococcusCoccidioidesBlastomycesPneumocystisAspergillus

ParasitesDirofilaria

Noninfectious diseases

SarcoidosisChronic beryllium diseaseHypersensitivity pneumonitisHot tub lungLymphoid interstitial pneumoniaWegener granulomatosisChurg-Strauss syndromeAspiration pneumoniaTalc granulomatosisRheumatoid noduleBronchocentric granulomatosis

Table 2. Key Diagnostic Features of Major Noninfectious Granulomatous Lung Diseases

Key Features Diagnosis

Prominent, well-formed, discrete, nonnecrotizing granulomas in pleura, interlobular septa, and walls ofbronchiolesa Sarcoidosis

Normal lung away from granulomas

Prominent interstitial chronic inflammation Hypersensitivity pneumonitisScattered, small, poorly formed granulomas or multinucleated giant cells in interstitium

Granulomas within bronchiolar lumens Hot tub lungHistory of hot tub useb

Suppurative granulomas with dirty necrosis Wegener granulomatosisNecrotizing vasculitis

Necrotizing granulomas Churg-Strauss syndromeNecrotizing vasculitisProminent eosinophils

Vegetable material surrounded by foreign bodytype granulomas or multinucleated giant cells Aspiration pneumonia

Interstitial foreign bodytype granulomas containing talc, microcrystalline cellulose, or crospovidone Talc granulomatosis

Active, seropositive rheumatoid arthritisb Rheumatoid noduleMultiple, bilateral lung nodulesSubpleural necrotizing granuloma

a Features not consistent with sarcoidosis include extensive necrosis or suppuration, interstitial inflammation away from the granulomas,

organizing pneumonia, granulomas within alveolar or bronchiolar airspaces, numerous eosinophils, and vegetable material.b Clinical information essential for diagnosis.

668 Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

3/24

stain is preferable, primarily because periodic acidSchiffprovides less contrast between fungi and backgrounddebris.4,7,14,15 Immunofluorescent and immunohistochemicaltechniques are more specific but have their limitations,7,16

the most important of which is lack of widespread

availability. For mycobacteria, an alternative to the ZNstain is the auramine/auramine-rhodamine fluorescencetechnique, which has been shown to be equivalent to cultureand superior to conventional acid-fast stains in sensitivi-ty.1,9,17,18 When H&E-stained sections have been examined,we recommend examining the GMS-stained sections beforethe more time-consuming ZN-stained sections. Scanning ata relatively low magnification (310 ocular, 320 objective)suffices to pick out most organisms, although Histoplasmamay be missed without a careful search with a 340objective. If results with the GMS stain are negative, thepathologist should then spend more time examining theZN-stained sections, hunting with a 340 objective formycobacteria, which are often few and difficult to find.

The morphologic features of the common fungal causesof lung granulomas are compared in Table 3. It is importantto remember that GMS is not a specific stain formicroorganisms, as it often stains mucin, elastic tissue,and dust particles in the background lung. Dust and pollenparticles pose a particular challenge because they maymimic the appearance of fungal yeasts. However, theseparticles are smaller in size and lack the characteristicshapes and budding forms associated with fungal yeasts.Mycobacterial organisms may occasionally be seen withGMS stains in certain cases and should not be dismissed asan artifact. It is also important to note that, on occasion, apoorly performed GMS stain may yield falsely negative

results; thus, it is important to check standard tissuecontrols in every case. Histoplasma yeasts in necrotizinggranulomas pose a particularly difficult problem becausethey may stain very weakly with GMS and be overlooked.7,10

Fungi of any type may also be missed if they are few.Regarding the ZN stain, the most important point to

remember is that, in most cases, mycobacteria are few anddifficult to find, partly because of the use of xylene inroutine processing.19 Therefore, cursory scanning at lowmagnification will miss most mycobacteria. We recommendspending at least a few minutes at high magnification (310ocular lens, 340 objective) hunting for mycobacteria in thenecrotic area of each necrotizing granuloma, constantly

adjusting the fine focus to ensure detection of organismsthat appear only on certain planes. Other authors go

further and use a high-power oil immersion objective.13,20

Organisms are by far more common in the center of thenecrosis10,13but may occasionally be found in the peripheryof the necrosis or even within the cellular granulomatousrim. It is not uncommon to examine several large

necrotizing granulomas and find only a few mycobacteria.When mycobacteria are identified, the next step, for thepurpose of choosing appropriate antibiotic therapy, is todifferentiate between tuberculous and nontuberculousmycobacteria. Unfortunately, the morphologic appearanceof mycobacteria on histologic sections is not reliable forspeciation. The published literature on speciation ofmycobacteria by using microscopic morphologic featuresof the organisms is based mostly on smears made frommicrobiologic cultures rather than formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded histologic material. Histologic studies that claimdistinctive morphologic features for particular mycobacte-rial species have included only nontuberculous mycobacte-ria,2123 and no data exist to show the accuracy ofmycobacterial subtyping by pathologists blinded to cultureresults. Even in smears made from microbiologic culturematerial, morphologic features such as cording, beading, orsize, although associated with certain species, do not allowaccurate or definitive speciation of mycobacteria.2426

Currently, the only definitive methods of mycobacterialspeciation are microbiologic culture and molecular meth-ods such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (seebelow). In most cases, speciation is not a problem becauseculture test results are also positive. In fact, mycobacteriaoften grow in cultures even when special staining ofhistologic material shows negative results.1,10,18,23,27,28 Whenresults with histologic special stains are positive but those

of cultures are negative,10,18,28,29

or when biopsied tissue wasnot submitted for culture, PCR is the only means ofdetermining the species of the organism. Finally, if PCRyields a negative result or is unavailable, the clinician mayelect to initiate empiric therapy.

Role of PCR and Other Molecular Methods forDetection and Speciation of Mycobacteria.Patholo-gists and clinicians are sometimes faced with the difficultsituation whereby mycobacteria are identified by histo-logic methods but speciation is not possible because nospecimen was submitted for culture or culture results arenegative. In an attempt to find a solution to this problem,the role of PCR and other molecular methods in the

detection and speciation of mycobacteria in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue has come under intense

Table 3. Morphologic Features of the Common Fungi Causing Granulomatous Lung Disease

Histoplasma Cryptococcus Coccidioides Blastomyces

Visualized on hematoxylin-eosin

No (in necrotizing granulomas) Yes Yes YesYes (in disseminated

histoplasmosis)Spherules and endospores No No Yes NoUsual sizea Small Small Large Large

3 mm 47 mm 3060 mm (spherules)25 mm (endospores)

815 mm

Shape Mostly oval, often tapered atone or both ends

Round Round or fragmented (spherules) RoundRound (endospores)

Size variation Minimal Marked Marked ConsiderableBudding Narrow based Occasional Absent Broad basedNuclei Single (when intracellular) None None MultipleStaining with mucicarmine Absent Usual, strong Absent Occasional,

weaka Sizes listed are the usual sizes encountered. Greater size variation has been reported with most of the fungi listed2,4,7 but is unusual.

Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal 669

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

4/24

investigation.19,30,31 In general, these studies show that PCRis as sensitive as microbiologic cultures for the detection ofmycobacteria in formalin-fixed tissues and is moresensitive than ZN staining.19 It is also possible todetermine the species of organisms by this method.Currently, however, PCR for detection and speciation ofmycobacteria in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sec-tions is not in routine diagnostic use in most laboratoriesand remains restricted to a few reference centers.

How to Report the Presence of Organisms.Thesubtyping of infectious mycobacterial or fungal disease(acute histoplasmosis versus histoplasmoma, progressiveprimary tuberculosis versus secondary tuberculosis, etc.)often requires clinical and radiographic information that isusually unavailable to the pathologist. Therefore, for thepurposes of the pathology report, describing the tissuereaction and stating the organism present is sufficient in mostinstances. A pathologic diagnosis for a case in whichHistoplasma yeasts are identified within a necrotizinggranuloma would be described as necrotizing granuloma(Histoplasma identified). If more clinical information isavailable, a more specific diagnosis may be rendered. For

example, if Histoplasma yeasts are identified in a necrotizinggranuloma and the pathologist is provided with theinformation that the lesion is an incidentally detected solitarylung nodule, a diagnosis of histoplasmoma can be rendered.

Step 2: Identifying Histologic Features of NoninfectiousGranulomatous Lung Diseases

The key diagnostic features of the common noninfec-tious granulomatous lung diseases are listed in Table 2.These are the major features that are required for apathologic diagnosis. In the absence of these features, adefinitive pathologic diagnosis is usually not possible anda descriptive diagnosis must suffice. Note that somediagnoses require clinical input, while others can berendered (or suggested) solely on the basis of theirhistologic features. We recommend using Table 2 toquickly narrow the differential diagnosis. Details of thepathologic findings and the differential diagnosis can thenbe obtained from the text (see below).

Step 3: Review of Special Stains and Descriptive Diagnoses

What to Do When Organisms Are Not Found in aGranuloma.Often, organisms are not found withingranulomas despite a meticulous search. Even in necrotiz-ing granulomas, this is a fairly frequent scenario.10,13 In suchcases, the most productive next step for the pathologist is toreevaluate the special stains: reexamination of the GMS-

stained sections, in particular, results in the detection ofseveral cases of initially overlooked Histoplasma infection(S.M., unpublished data, March 2009). If the necrotic portionof the granuloma is not represented on the slide with thespecial stain, it may be productive to recut the block andrepeat the stain. In a study by Goodwin and Snell,32 10 of 17histoplasmomas were diagnosed only after an effort wasmade to include the necrotic center in a recut. If some blockswith necrosis are not initially stained with special stains,staining these may also be productive. Ulbright andKatzenstein10 showed that examining 2 blocks with necrosisis adequate in most cases, with the caveat that examinationof more sections is probably indicated when the histologic

appearance is especially suggestive of infection or when aspecific noninfectious diagnosis is being considered.

Despite these steps, a substantial proportion of necro-tizing granulomas remain unexplained. Ulbright andKatzenstein10 suggested that such cases might representinfectious granulomas in whichthe organism has been killedor removed by the inflammatory reaction. In such cases, werecommend issuing a descriptive diagnosis including thepresence/absence of necrosis and the absence of identifiableorganisms. In the caseof necrotizinggranulomas,a commentsuch as the etiology is most likely infectious despitenegative special stains may be appropriate. In some casesin which organisms cannot be found by histologic examina-tion, results of cultures may be productive. From surgicallyexcised granulomas, mycobacteria (mainly nontuberculous)often grow in culture despite negative ZN and auramine-rhodamine staining results on histologic material.1 Finally,clinicians may classify a small number of unexplainednecrotizing granulomas as histoplasmosis or anti-neutrophilcytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)related vasculitides on thebasis of serologic studies.

MYCOBACTERIA

Tuberculosis

Worldwide, Mycobacterium tuberculosis outnumbersnontuberculous mycobacteria and fungi such as Histoplas-ma as the leading cause of granulomatous lung disease.Considering the prevalence of the disease, there aresurprisingly few papers in the current literature on thehistologic features of culture-proven pulmonary tubercu-losis. The few histologic studies available are mainly fromthe years when the mere presence of necrotizing granu-lomas was considered diagnostic of tuberculosis.13,33 Infact, before 1953, all rounded granulomas of the lung wereassumed to be tuberculomas.13,32

The granulomas of tuberculosis are typically necrotiz-ing (Figure 1, A) but may be nonnecrotizing or a mix of

both types.20,34

As discussed in step 3 above, acid-fastorganisms (Figure 1, B) may be few and difficult to find.The granulomas of tuberculosis may be randomly locatedor bronchiolocentric, although it is important to rememberthat granulomas may involve bronchi and bronchioles invirtually any infection,35 as well as sarcoidosis andhypersensitivity pneumonitis. The granulomas of tuber-culosis may also involve blood vessels, although lessfrequently than in sarcoidosis.36 The features may remote-ly resemble a true primary vasculitic disorder, such asWegener granulomatosis. The histologic appearance oftuberculous granulomas may be indistinguishable fromthose of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection.28,37,38 Thiswas most elegantly demonstrated in a 1963 study by

Corpe and Stergus37 in which 27 pathologists withexpertise in mycobacterial disease were blinded to cultureresults and asked whether histologic changes on 25 slideswere due to M tuberculosis or Runyon group III non-tuberculous mycobacteria. In most cases, the pathologistscould not differentiate between the 2 infections, and whenthey felt they could, they were often mistaken. Fungi suchas Histoplasma and Coccidioides may also produce a tissueresponse identical to tuberculosis.7 Because the histologicfeatures of tuberculosis are not organism-specific, thediagnosis rests on detection (and subsequent speciation)of mycobacteria. Issues relating to identification andspeciation of mycobacteria are discussed in detail in

Examining Special Stains for Organisms (see 2nd pageof this article).

670 Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

5/24

Nontuberculous Mycobacteria

In the United States, NTM are increasingly beingrecognized as an important cause of lung disease. In the

past, lung infection by NTM was thought to occur mainlyin the setting of immunodeficiency or preexisting lung

disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease orcystic fibrosis. It is now well known that NTM-related

Figure 1. Infectious necrotizing granulomas. A, Tuberculosis. Necrotizing granuloma. B, Same case as A. Single acid-fast bacterium (arrow). C,Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Mycobacterium intracellulare was isolated in cultures. Necrotizing granuloma with abundant necrosis,indistinguishable from tuberculosis. Epithelioid histiocytes are at bottom right. D, Same case as C. Mycobacteria (arrows) are identical in morphologyto the single organism seen in B. E, Histoplasmoma. Necrotizing granuloma larger than, but otherwise identical to, the granulomas in A and C. F,Same case as E. Histoplasma yeasts (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications 3100 [A, C, and E]; Ziehl-Neelsen, original magnifications 31600[B and D]; Grocott methenamine silver, original magnification3400 [F]).

Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal 671

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

6/24

lung disease also occurs in immunocompetent individualswithout preexisting lung disease.39

In immunocompromised patients, such as those withthe acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), NTMinfection is characterized by collections of mycobacteria-laden foamy histiocytes, poorly formed granulomas, orthe lack of any significant inflammatory response.40

Mycobacteria in this form of NTM disease are numerousand easy to find, and culture results are usually positive.

In immunocompetent patients, NTM infection has beenassociated with a wide variety of histologic findings,including granulomatous inflammation indistinguishablefrom tuberculosis (Figure 1, C and D, and Tuberculosisabove).28,37,38 Like tuberculosis, both necrotizing andnonnecrotizing granulomas may be found23,28 and thegranulomas may be peribronchiolar. Cases with nongran-ulomatous inflammation have also been described, butsince NTM are frequent colonizers of the respiratory tract,it is debatable whether NTM infection in such cases isetiologic or merely coincidental.23,28 Nontuberculous my-cobacteria infection may also be associated with airwaydisease, manifested histologically as bronchiectasis or

chronic bronchiolitis.41,42

Nontuberculous mycobacteriahave been isolated from cases of the middle lobesyndrome, suggesting a predilection for this location.43

Definitive diagnosis of NTM disease rests on identificationand speciation of mycobacteria (see Examining SpecialStains for Organisms on the 2nd page of this article).

Finally, exposure to aerosolized NTM can cause ahypersensitivity pneumonitis-like illness known as hottub lung. In keeping with current concepts of thepathogenesis of this condition, this entity will be dis-cussed in the section on noninfectious granulomatouslung disease (below).

FUNGI

The tissue reaction to the common pulmonary fungidiscussed in this section varies greatly, depending on thesize of the inoculum, the duration since exposure, and theimmunologic status of the host. The sequence of eventsand the wide variety of inflammatory responses andoutcomes are similar in many respects to mycobacterialinfections. In most immunocompetent individuals, expo-sure to a small inoculum leads to asymptomatic self-limited infection. Heavier exposure may lead to an acuteflulike or pneumonia-like illness (acute pulmonary histo-plasmosis, acute blastomycosis, or acute coccidioidomy-cosis/valley fever).4450 Such cases may be diagnosedclinically as influenza or community-acquired pneumo-nia. When the correct diagnosis is made, it is usually based

on serologic rather than histologic findings.49,51 Since abiopsy is rarely performed in acute disease, the pathologicfindings remain poorly described. Both asymptomaticinfection and acute symptomatic disease clear completelyin most cases.

In some individuals, healing is not accompanied bycomplete clearance of organisms. Instead, organisms persistin a walled-off nodule characterized by a well-formed,necrotizing granuloma similar to a tuberculoma (eg,histoplasmoma, cryptococcoma, coccidioidoma).1214,32,45,52,53

This is the most common form of granulomatous fungaldisease encountered by surgical pathologists. These lesionsare biopsied or resected because they form nodules, which

are difficult to separate from malignant tumors on clinicaland radiographic grounds.

In some patients, usually those with an underlyingpredisposing illness, infection progresses instead of beingcleared or contained. This results in chronic symptomaticfungal lung disease (eg, chronic pulmonary histoplasmo-sis, chronic blastomycosis, persistent coccidioidal pneu-monia).45,54 The pathologic manifestaton of this form offungal lung disease is complex and includes necrotizinggranulomas in combination with evidence of the under-lying predisposing illness (such as emphysema) orsuperimposed complications (such as cavities).

The final piece in the spectrum of fungal lung diseasedoes not typically involve granulomatous inflammationbut is mentioned here to give the reader a sense of thegamut of tissue responses to fungal organisms. This typeof disease occurs in immunocompromised individuals,who often develop disseminated infection characterizedby unchecked proliferation of organisms accompaniedby little or no inflammatory response (eg, disseminatedhistoplasmosis, disseminated blastomycosis, disseminat-ed cryptococcosis, disseminated coccidioidomycosis).55,56

Granulomas are absent, and if present, are poorly formed.This form of disease is often widespread, with a

predilection for the lymphohematopoietic system, but itmay also involve the lungs.

Histoplasma

Lung involvement in Histoplasma infection takes manyforms, but the tissue reaction can be broadly divided into 3main types. The first is an intra-alveolar lymphohistiocyticinfiltrate with small granulomas and variable necrosis,seen in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis. The second iswell-formed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation,exemplified by histoplasmomas but also seen in chronicpulmonary histoplasmosis.1214,32,54 The third type of tissuereaction consists of sheets of histiocytes within theinterstitium, packed with numerous organisms, as seen

in disseminated histoplasmosis.55

By far the most commonform of Histoplasma-related lung disease encountered bysurgical pathologists is a histoplasmoma (Figures 1, E andF, and 2, A and B). The classic lesion is a large nodule withabundant central necrosis surrounded by a thin rim ofepithelioid histiocytes and a fibrotic capsule of variablethickness (Figure 1, E). Small calcific particles may bepresent within the necrosis or the calcification may bemore irregular. Overall, the histologic appearance isidentical to a tuberculoma or coccidioidoma.13 Bloodvessels in and around the granuloma may show aprominent nonnecrotizing vasculitis, as noted previouslyfor mycobacterial disease.10,54 It is important to note thatthe vasculitis in histoplasmosis and other granuloma-

tous infections is a secondary phenomenon related to thegranulomatous inflammation, in contrast to a trueprimary vasculitis such as Wegener granulomatosis. Indescribing cases with such vascular changes, it isadvisable for pathologists to avoid the term vasculitis intheir reports because clinicians may misconstrue this as atrue primary vasculitis. The vascular changes in Histo-plasma infection often result in parenchymal necrosis withan infarctlike quality; that is, ghosts of alveoli can bediscerned within the necrotic areas.14,32,54,57 As with otherinfections, smaller satellite, nonnecrotizing granulomasand areas of organizing pneumonia may be scattered inthe lung parenchyma around the main necrotizing

granuloma. With time, the necrotic center is progressivelyreplaced by fibrosis and calcification.

672 Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

7/24

Figure 2. Fungal granulomas. A, Necrotic center of a histoplasmoma. Organisms are not visible on a hematoxylin-eosin stain, even at highmagnification. B, Same case as A. Uniform, mostly ovalHistoplasma yeasts are clearly visible on a silver stain. Note that some organisms are taperedat one or both ends. C, Nonnecrotizing granulomas containingCryptococcus. Round yeasts with blue-gray cell walls are visible within histiocytes.Note the characteristic halo around the organisms. D, Same case as C. Note the mostly round shape and marked variation in size. E,Granulomatous Pneumocystis pneumonia. Histiocytes palisade loosely around an intra-alveolar eosinophilic exudate. F, Same case as E. Small,round, yeastlike Pneumocystis cysts within an alveolar space. Crescentlike forms are characteristically seen (hematoxylin-eosin, originalmagnifications 3400 [A, C, and E]; Grocott methenamine silver, original magnifications31600 [B, D, and F]).

Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal 673

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

8/24

One key point to remember is that the visibility ofHistoplasma on H&E-stained sections depends on thehistologic context. WhileHistoplasma is readily identifiablewithin macrophages in disseminated histoplasmosis, it isnot visible on H&E-stained sections within necrotizinggranulomas (histoplasmomas).1013 Although organismsare present within the necrotic areas, they cannot beresolved from the background necrotic debris on H&E-stained sections (Figure 2, A). Structures that at firstglance appear to beHistoplasma yeasts are invariably smallmicrocalcifications, which are common in old necrotizinggranulomas of any etiology.10,11 They can be distinguishedfrom fungal yeasts because they are usually GMS-negative, basophilic, and pleomorphic. Demonstration ofHistoplasma in necrotizing granulomas is best accom-plished by performing GMS staining. The presence ofyeast forms that are not appreciated on H&E, but visibleon GMS, is virtually pathognomonic of Histoplasma. Witha GMS stain, Histoplasma yeasts are small, uniform, andoval (Figures 1, F, and 2, B). A characteristic feature is thatsome taper to a point at one end or sometimes both ends.They are scattered within the necrotic center of the

granuloma and may be present in clusters or singly.Narrow-based budding, although often cited as a charac-teristic finding, is not always identifiable, especially whenorganisms are few. Histoplasma yeasts tend to be a mixtureof lightly stained, hollow-appearing forms with thin,delicate outlines and more darkly stained solid forms,with the staining characteristics varying with the strengthof the stain in an individual case.10,11 Rare hyphal formshave also been described.11,58Histoplasma seldom grows inculture from histoplasmomas probably because theorganisms are nonviable in most of these lesions.10,13,59

Therefore, histopathologic examination is often the onlymeans of confirming the diagnosis.14

Histoplasma may be confused with Cryptococcus, which

can be associated with an identical granulomatousresponse. Small, capsule-deficient forms of Cryptococcuspose a particular challenge. A helpful morphologic featurein the differential diagnosis is that Histoplasma cannot beseen (in necrotizing granulomas) on H&E-stained sections,whereas Cryptococcus yeasts can (Figure 2, A and C). Bothorganisms are highlighted by the GMS stain, whereby themain differentiating features are the uniform size, ovalshape, and occasional tapered forms of Histoplasma asopposed to the nonuniform size, round shape, and lack oftapering ofCryptococcus (Figure 2, B and D).

Histoplasma may also be confused with Pneumocystis.Fortunately, this is not a common problem because, inmost cases, Pneumocystis pneumonia is characterized by

an intra-alveolar frothy exudate, while Histoplasma infec-tion is characterized by a necrotizing granuloma. Howev-er, in 5% to 17% of cases, Pneumocystis may elicit agranulomatous response6062 (Figure 2, E). Such cases,termed granulomatous Pneumocystis pneumonia, canmimic acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, since bothconditions feature granulomas. While the frothy intra-alveolar exudate of Pneumocystis differs from thefibrinous intra-alveolar exudate of acute pulmonaryhistoplasmosis, it is not always present. Morphologicappearance of the organisms with GMS is the keydifferentiating feature. Although Histoplasma and Pneu-mocystis are similar in size, Pneumocystis cysts are round

rather than oval, are often crescent-shaped or sickle-shaped (Figure 2, F), and do not bud or taper. In

difficult cases, results of microbiologic cultures orimmunohistochemical stains may be helpful.

Cryptococcus

Cryptococcosis of the lung includes a wide spectrum oftissue reactions6365 that depend on the immunologic statusof the host. Immunocompetent patients tend to developgranulomas, whereas the reaction is more variable inimmunocompromised patients. The typical granuloma-tous reaction to Cryptococcus is confluent nonnecrotizinggranulomatous inflammation with numerous multinucle-ated giant cells and scattered chronic inflammation(Figures 2, C, and 3, A). Multinucleated giant cells maypredominate over granulomas. At low magnification, thepresence of engulfed Cryptococcus yeasts imparts a bubblyappearance to the cytoplasm of histiocytes and multinu-cleated giant cells. At high magnification, Cryptococcusyeasts can be identified by careful examination withinmultinucleated giant cells and granulomas (Figures 2, C,and 3, A). Cryptococcus may also be found withinnecrotizing granulomas (cryptococcomas) similar to thoseseen with mycobacterial or other fungal infections. In this

setting, too, organisms are identifiable, both within thenecrotic areas and the surrounding granulomatous rim.10

Finally, in immunocompromised patients, innumerableCryptococcus yeasts grow in sheets within alveolar spaces,alveolar septa (interstitium), and alveolar septal capillar-ies and bronchioles, with little or no inflammatoryreaction.6567 Not surprisingly, patients with AIDS occa-sionally have concurrent Pneumocystis infection.66

On H&E-stained sections, Cryptococcus yeasts are roundwith well-defined but pale-staining blue-gray walls(Figures 2, C, and 3, A). Because of the pale-stainingwalls, the organisms may easily be overlooked at lowmagnification.7 Characteristically, the organism retractsfrom the cytoplasm of the cell that engulfs it, resulting inthe formation of a halo around the organism. Grocottmethenamine silver stains the organisms well and, as withother fungi, often highlights far more organisms thaninitially appreciated (Figures 2, D, and 3, B). The capsuleofCryptococcus stains deep red with mucicarmine and thisfeature may be used to support the diagnosis.7,66 However,it is important to remember that absence of mucicarminestaining does not exclude Cryptococcus because theorganism may lack a capsule (capsule-deficient Crypto-coccus).66,6870 In such cases, the Fontana-Masson stain isuseful because it stains the cell wall of Cryptococcus,including that of capsule-deficient forms.15,70

The differential diagnosis includes Histoplasma and

Blastomyces.70

For details of the features useful in thedifferential diagnosis, see Table 3 and the sections onHistoplasma and Blastomyces.

Coccidioides

The most common form of Coccidioides infectionencountered by the surgical pathologist is the necrotizinggranuloma (coccidioidoma).45,52 Eosinophils may be nu-merous,71 scant, or absent and neutrophils may beprominent. As with other infections, the granulomasmay be peribronchiolar or may communicate with ordestroy bronchioles. An accompanying nonnecrotizingvasculitis, as noted previously with other infections, may

be present.

10

Smaller satellite, nonnecrotizing granulomasare often seen in surgically resected specimens. The

674 Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

9/24

Figure 3. Fungal granulomas. A, Cryptococcus. Numerous round yeasts within histiocytes, some surrounded by haloes. B, Same case as A. Notepleomorphism and compare size with D and F. C, Coccidioides in a patient with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Both endospore-filled and emptyspherules are present. Note similarity of endospores toCryptococcus (A) and of endospore-filled spherules toBlastomyces (E). D, Same case as C. E,Blastomyces. Single, large, thick-walled, nucleated yeast (arrow) within multinucleated giant cell. Note characteristic neutrophilic response. F, Samecase as E. Large yeast with single broad-based bud (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications 3400 [A, C, and E]; Grocott methenamine silver,original magnifications3400 [B, D, and F]).

Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal 675

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

10/24

overall picture is indistinguishable from granulomascaused by mycobacteria or other fungi.13 Demonstrationof organisms is therefore essential for diagnosis.

Coccidioides organisms are most often found within thenecrotic centers of necrotizing granulomas, although theyshow less of a propensity for the center than Histoplasmaand may also be found within nonnecrotizing granulo-mas. The organisms consist of large, thick-walled,spherical structures (spherules) filled with smalleryeastlike structures (endospores) (Figure 3, C and D).Not uncommonly, spherules are found in a ruptured,fragmented, emptying or empty state. Endospores ofvarious sizes may lie scattered in the necrotic debris,mimicking other fungal yeasts. Neither spherules norendospores show budding. Although some authors havereported difficulty in detecting organisms on H&E-stained sections,45 they are usually easily found.7,52 Aswith other fungi, the GMS stain reveals more organismsthan initially appreciated on H&E-stained sections.Grocott methenamine silver highlights the spherules aswell as the endospores. A mycelial form of the fungus,consisting of septate hyphae with arthrospores, may also

be encountered if there is communication with ambienttemperature.45,52 As with Histoplasma, the organism maynot grow in cultures (especially from coccidioidomas)10; insuch cases, histologic examination may be the only meansof establishing the diagnosis.

If spherules and endospores are both present (Figure 3,C and D), the diagnosis is straightforward. However, inmany cases it may be difficult to find these characteristicfungal structures. In the absence of one or the other form,differentiation from Blastomyces can be difficult (seeTable 3 and Blastomyces below). Size of the organismis a helpful feature because Coccidioides spherules areusually larger than Blastomyces yeasts. Broad-basedbudding is a feature of Blastomyces but not ofCoccidioides.

In difficult cases, correlation with the results of microbi-ologic cultures is prudent.

Blastomyces

Infection with Blastomyces is uncommon. It must besuspected when granulomas or multinucleated giant cellsare accompanied by acute inflammation1,68,72 (Figure 3, Eand F). Classic cases show granulomas with franklysuppurative centers, in contrast to the pink or slightlydirty necrosis seen in granulomas due to otherorganisms. As with other infections, the granulomasmay be bronchiolocentric.35 The large, thick-walled yeastforms of Blastomyces can be identified on H&E-stainedsections, although they may be few and difficult to find.

Broad-based budding is fairly characteristic but notalways present. On H&E-stained sections, nuclear mate-rial (multiple nuclei) can often be identified within theyeasts; this can mimic the endospore-filled spherules ofCoccidioides (compare Figure 3, C, and 3, E).

Blastomyces yeasts are larger than the yeasts of Histo-plasma and Cryptococcus and the endospores ofCoccidioidesbut smaller than Coccidioides spherules (Table 3); however,enough overlap and size variation exists to cause potentialconfusion between these organisms7,73,74 (Figure 3, Athrough F). Mucicarmine staining, while characteristic ofCryptococcus, can also be seen with Blastomyces, although ittends to be weaker in the latter8,74 and has been attributed

by some authors

7

to overstaining. Multinucleation andbroad-based budding are features of Blastomyces that are

absent in Cryptococcus. Blastomyces differs from Histoplas-ma in that it is visible on H&E-stained sections, has a thickwall, broad-based budding, multiple nuclei, and asuppurative tissue reaction. Differentiation of Blastomycesfrom Coccidioides can be difficult. For features helpful inseparating the two, see Figure 3, C through F; Table 3; andCoccidioides above.

Pneumocystis

Most pathologists are familiar with the usual picture ofPneumocystis pneumonia, which is a frothy, eosinophilic,intra-alveolar exudate accompanied by mild interstitialchronic inflammation. In 5% to 17% of cases61,62 agranulomatous reaction is encountered (Figure 2, E). Inmost, it consists of poorly formed intra-alveolar granulo-mas characterized by epithelioid histiocytes palisadingloosely around an eosinophilic exudate. Some cases mayshow intra-alveolar nonnecrotizing granulomas withoutan exudate,75 scattered multinucleated giant cells, orga-nizing granulomatous pneumonia,60 or well-formed gran-ulomas with or without central necrosis.

In immunocompromised patients, the above histologic

appearance is highly suggestive of granulomatous Pneu-mocystis pneumonia and calls for especially close scrutinyof the GMS-stained section. A frothy intra-alveolarexudate should also raise the possibility of Pneumocystis,although it is not always present. Organisms can be scarceand difficult to find. They consist of small, round, sickle-shaped or crescent-shaped cysts (Figure 2, F). Differenti-ation from acute pulmonary histoplasmosis is discussedin the section on Histoplasma.

Aspergillus

Aspergillus may cause invasive, saprophytic, or allergiclung disease,76 depending primarily on the immune status

of the host. The 2 most common forms of lung involvementby Aspergillus (aspergilloma and invasive aspergillosis) donot feature granulomas. However, granulomas are aprominent feature of 2 less common forms of pulmonaryaspergillosis (chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosisand allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis).

In the rare condition known as chronic necrotizingpulmonary aspergillosis, Aspergillus infection results insemi-invasive, chronic, indolent, cavitary disease inpatients who have preexisting chronic lung disease orare mildly immunocompromised.77 The histologic pictureis characterized by necrotizing granulomas containingAspergillus hyphae.78 The presence of granulomas isindicative of limited tissue invasion. The granulomas

may cause extensive parenchymal consolidation, maylead to bronchiectatic cavities, or may be exclusivelybronchocentric. The bronchocentric cases may be accom-panied by nonnecrotizing granulomas in a lymphangiticdistribution. A nonnecrotizing vasculitis can occur.Eosinophils are not prominent.

Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis should bedifferentiated from other forms ofAspergillus-related lungdisease. In mycetomas (aspergillomas), the fungal organ-isms do not invade the surrounding parenchyma or evokea granulomatous response. Allergic bronchopulmonaryfungal disease (see below) occurs in persons with asthmaand is easily differentiated from chronic necrotizing

pulmonary aspergillosis by the prominence of tissueeosinophils (see below). Invasive aspergillosis differs

676 Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

11/24

from chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis becauseit features vascular invasion by fungal hyphae andextensive parenchymal necrosis without granuloma for-mation.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is a noninva-sive form of Aspergillus lung disease characterized by ahypersensitivity response to Aspergillus antigens, occur-ring mostly in asthmatic patients.7981 Less commonly,other fungi such as Curvularia and Candida may causesimilar morphologic changes.82 Hypersensitivity to thefungus results in a distinctive tissue reaction characterizedby the triad of mucoid impaction of bronchi, broncho-centric granulomatosis, and eosinophilic pneumonia(Figure 4, A through D). Mucoid impaction of bronchi ischaracterized by obstruction of proximal bronchi by large,laminated, gelatinous mucus plugs filled with viable andnecrotic eosinophils, neutrophils, fibrin, and necroticdebris (Figure 4, A). Charcot-Leyden crystals are oftenpresent, reflecting the eosinophil-rich infiltrate (Figure 4,B). Aspergillus hyphae may be found within the mucus(Figure 4, B [inset]). Bronchocentric granulomatosis ischaracterized by necrotizing granulomas centered exclu-

sively on bronchi and bronchioles distal to the bronchiaffected by mucoid impaction (Figure 4, C). The necroticcenters of the granulomas are rich in eosinophils andnecrotic debris (Figure 4, D). Eosinophilic pneumonia isusually a focal finding in allergic bronchopulmonaryaspergillosis. The main histologic feature is filling of thealveolar spaces with eosinophils. Histiocytes often accom-pany the eosinophil-rich infiltrate. The interstitium isusually thickened by a combination of eosinophils,lymphocytes, and plasma cells. A mild nonnecrotizingvasculitis may be present. The pathologic diagnosis ofallergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is confirmed bythe identification of Aspergillus hyphae scattered withinthe lumens of bronchi or bronchioles (Figure 4, B [inset]).

Organisms may be sparse, fragmented, and difficult todemonstrate, even with a GMS stain. Even in the absenceof demonstrable fungi, the triad of histologic featuresdescribed above strongly suggests the diagnosis. Thedifferential diagnosis is broader when individual compo-nents of the triad are present in isolation.

Several entities enter the differential diagnosis, includ-ing (1) other forms of Aspergillus lung disease; (2) mucoidimpaction of bronchi, bronchocentric granulomatosis, oreosinophilic pneumonia, occurring in isolation; and (3)diseases due to other fungi with septate hyphae. Differ-entiation from other forms of Aspergillus lung disease isdiscussed in the preceding section on chronic necrotizingpulmonary aspergillosis. Each of the features of the

histologic triad of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillo-sis can occur in isolation in other settings. Mucoidimpaction of bronchi can occur in cystic fibrosis or chronicbronchitis.83 Bronchocentric granulomatosis may occur inother infections.35 Eosinophilic pneumonia occurs inseveral other settings, including drug reactions, parasiticand coccidioidal infection, Churg-Strauss syndrome, andidiopathic disease. Therefore, it is a combination offeatures, rather than any individual finding, that raisesthe possibility of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.Definitive diagnosis requires identification of fungalhyphae. The classic appearance of Aspergillus (septatehyphae with narrow-angle branching) is well known to

most pathologists, but it must be stressed that thisappearance is not specific for Aspergillus.7 It can

occasionally be seen in other fungi such as Pseudal-lescheria84,85 and Fusarium. Cultures are required fordefinitive identification.

PARASITES

Dirofilaria

Dirofilaria (the dog heartworm) is the most commonparasite associated with a granulomatous reaction in the

lung. The organism is a filarial nematode that typicallyinfects dogs but may rarely infect humans via a mosquitovector. Human pulmonary dirofilariasis is rare. Almost allreported cases in the United States have been from theeastern half of the country and Texas.86,87 The wormresides in the right side of the heart, from where itembolizes to the lung; there, it is most often found within athrombosed pulmonary artery surrounded by infarct-likenecrosis.88 A granulomatous reaction is seen in theadjacent tissue in about one-third of cases, eosinophilsare present in around two-thirds, and a nonnecrotizingvasculitis is seen in approximately half.89 The diagnosisrests on identification of the organism, which is often

fragmented, degenerated, and calcified. It is usually large,eosinophilic and oval, with a complex internal structureand a lighter-staining, multilayered, smooth cuticle.90

NONINFECTIOUS GRANULOMATOUS LUNG DISEASE

Sarcoidosis

In the United States, sarcoidosis is the most commonnoninfectious cause of lung granulomas encountered bysurgical pathologists.1 However, it is important to em-phasize at the outset that nonnecrotizing granulomasoccur in the lung in several conditions other thansarcoidosis and that none of the histologic features listedbelow are absolutely pathognomonic for sarcoidosis.91

Histologically, sarcoidosis is characterized by discrete,well-formed, interstitial nonnecrotizing granulomas (Fig-ure 5, A and B). Although nonnecrotizing granulomaspredominate, small foci of pink necrosis are occasionallyencountered.1,92,93 An underappreciated feature of sarcoid-osis is the lymphangitic (following the lymphatics)distribution of the granulomas (Figure 5, A). In the lung,lymphatics run in the pleura, interlobular septa, andbronchovascular bundles (bronchi/bronchioles and arter-ies); it is in these locations that the granulomas ofsarcoidosis are found.93,94 This distribution also explainswhy transbronchial biopsies are so effective in detectingsarcoid granulomas.95 Needless to say, a lymphangiticdistribution can only be appreciated in a surgical biopsy

(or larger specimen), not in a transbronchial biopsy. Afrequent finding in sarcoidosis is the presence of intracy-toplasmic inclusions (Figure 6, A and B), which arethought to represent (endogenous) products of macro-phage metabolism. These include pink spiderlike struc-tures (asteroid bodies) (Figure 6, A), basophilic concentriccalcifications (Schaumann bodies), and calcium oxalatecrystals.96 Calcium oxalate crystals and Schaumann bodiesare birefringent (Figure 6, B) and must not be mistaken forforeign (exogenous) material.97 Although these inclusionsare more frequent and numerous in sarcoidosis, they arealso found in other granulomatous diseases such ashypersensitivity pneumonitis (Figure 6, C and D), chronic

beryllium disease, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis,

96

nontu-berculous mycobacterial infection,97 and talc granuloma-

Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal 677

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

12/24

tosis (Figure 6, E and F). In an individual case, therefore,they cannot be used as a specific indicator of sarcoidosis.

Other frequent findings in sarcoidosis are concentric,lamellated fibrosis around granulomas (Figure 5, B),hyalinization of and within granulomas, granulomatous

vasculitis,36,98 absence of granulomas within air spaces,absence of organizing pneumonia, and absence ofinterstitial inflammation away from the granulomas.2,3,94

The differential diagnosis includes infection, hypersen-sitivity pneumonitis, hot tub lung, and chronic berylliumdisease (Figure 5, A through F). As discussed previously,infectious granulomas may be nonnecrotizing, wellformed (sarcoidlike), and peribronchiolar. A carefulsearch for organisms is therefore mandatory beforesuggesting a diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Organisms espe-cially likely to cause a similar histologic picture includemycobacteria and Cryptococcus. Although the presence ofnecrosis does not exclude sarcoidosis, it should prompt a

more vigorous search for organisms.

91

Other featurescommon in infection but absent in sarcoidosis are

organizing pneumonia and extensive necrosis or suppu-ration. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis enters the differen-tial diagnosis because of the presence of nonnecrotizinggranulomas and frequent intracytoplasmic inclusions(Figure 6, C and D). It is usually easily differentiated

from sarcoidosis because the picture is dominated byinterstitial chronic inflammation rather than granulomas(Figure 5, C). Interstitial inflammation also involvesalveolar septa away from the granulomas in hypersensi-tivity pneumonitis, while it is limited to the granuloma-tous foci in sarcoidosis. A lymphangitic distribution, well-formed granulomas, and granulomatous vasculitis occurin sarcoidosis but not in hypersensitivity pneumonitis.Hot tub lung can be a more challenging problem becausegranulomas are more prominent than in hypersensitivitypneumonitis and thus closer in appearance to sarcoidosis(Figure 5, E and F). The main discriminant histologicfeature is that granulomas of hot tub lung occur

predominantly within air spaces (mainly the lumens ofsmall bronchioles), while those of sarcoidosis are intersti-

Figure 4. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. A, Mucoid impaction of bronchi. A dilated bronchus is filled with lamellated, eosinophilicdebris. B, Same case as A. The intrabronchial debris is composed of necrotic eosinophils and mucus. Note characteristic Charcot-Leyden crystals(arrow). Branching hyphae are present within the debris (inset). C, Same case as A, showing bronchocentric granulomatosis. Necrotizinggranulomatous inflammation (arrows) destroying a bronchiole (arrowhead). Note the necrotic debris filling the bronchiolar lumen. D, Same case asA showing a bronchocentric necrotizing granuloma at high magnification. Palisading histiocytes at bottom left, necrosis rich in eosinophils at topright (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications 320 [A], 3400 [B], 340 [C], 3200 [D]; Grocott methenamine silver, original magnification3400 [B, inset]).

678 Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

13/24

Figure 5. Noninfectious nonnecrotizing granulomas. A, Sarcoidosis. Granulomas are distributed along the pleura (top), interlobular septum(arrows) and bronchovascular bundles (arrowhead) (lymphangitic distribution). The inflammation is localized to the granulomas and does notextend into the adjacent lung parenchyma. B, Sarcoidosis. Well-formed, nonnecrotizing granuloma surrounded by characteristic concentric fibrosis.C, Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The main abnormality is mild thickening of the alveolar septa (interstitium). Granulomas are not visible at thismagnification. D, Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Interstitial chronic inflammation with a loose cluster of histiocytes (poorly formed granuloma). E,Hot tub lung. The granulomas show a predilection for bronchioles (arrows). F, Hot tub lung. A well-formed, nonnecrotizing granuloma is seen withinan air space (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications320 [A, C, and E] and3200 [B, D, and F]).

Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal 679

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

14/24

Figure 6. Endogenous and exogenous material within granulomas. A, Asteroid body (endogenous) in sarcoidosis. B, Crystalline inclusion(endogenous) in sarcoidosis (the inclusion is birefringent [inset]). C, Needle-shaped, crystalline inclusion (endogenous) in hypersensitivitypneumonitis. D, Cholesterol cleft (endogenous) in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. E, Two asteroid bodies (endogenous) in talc granulomatosis.Exogenous material is also present (arrow). F, Microcrystalline cellulose (exogenous) in talc granulomatosis (birefringence [inset]). G, Vegetableparticles (exogenous) in aspiration pneumonia. Legumes of various kinds (lentils) share this morphology. H, Degenerated vegetable material

680 Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

15/24

tial. Lymphangitic granulomas and granulomatous vas-culitis favor sarcoidosis, while identification of mycobac-teria and a history of hot tub use support a diagnosis of hottub lung.

The main role of the pathologist in the diagnosis ofsarcoidosis is to exclude other etiologies. First, thespecimen should be carefully examined for organisms.Second, an attempt should be made to identify featuresthat are not consistent with sarcoidosis.99 Such features(used to argue for an alternative diagnosis) includegranulomas within alveolar or bronchiolar air spaces,organizing pneumonia, interstitial inflammation in alve-olar septa away from the granulomas, extensive necrosisor suppuration, numerous eosinophils, or vegetablematerial. If these features are present, sarcoidosis isunlikely, and this should be communicated clearly to theclinician.

In a surgical biopsy (or larger specimen) with well-formed nonnecrotizing granulomas distributed alonglymphatic pathways, in the absence of features that wouldargue against sarcoidosis, it is reasonable for a pathologistto state that the features are consistent with sarcoidosis.

In most transbronchial biopsy specimens, however, manyof the above features cannot be evaluated, and thereforemore caution must be exercised. It is acceptable with thesespecimens to simply diagnose nonnecrotizing granulo-mas and indicate in a comment that no organisms areidentified. One could also outline the differential diagno-sis or comment that the features are consistent withsarcoidosis in the appropriate clinical context, whilerealizing that the final diagnosis of sarcoidosis lies withthe clinician, who has access to the results of cultures andknowledge of the clinical and radiologic settings. Evenarmed with this information, the diagnosis of sarcoidosiscan be difficult because of the absence of a uniformly

accepted clinical or morphologic gold standard.Chronic Beryllium Disease

Chronic beryllium disease is characterized by a granu-lomatous reaction in the lung to inhaled beryllium. Thehistologic picture is characterized by nonnecrotizinggranulomas. The appearance is thought to mimic sarcoid-osis in almost every respect, including lymphangiticdistribution and hilar lymph node involvement.100 How-ever, illustrations of chronic beryllium disease in theliterature show interstitial inflammation and poorlyformed granulomas, the overall picture being moresimilar to hypersensitivity pneumonitis than sarcoido-sis.101,102 In a large histologic series, most cases showed

chronic interstitial inflammation with poorly formed towell-formed granulomas.101 A smaller fraction of caseswere described as having well-formed granulomas re-sembling sarcoidosis, but illustrations of these sarcoid-like cases show more interstitial inflammation thanusually encountered in sarcoidosis. Like sarcoidosis (andhypersensitivity pneumonitis), inclusions of various kinds(Schaumann bodies, asteroid bodies, crystals) have beendocumented.

Pulmonary granulomas are part of the diagnosticcriteria for chronic beryllium disease.100 However, toobtain a definitive diagnosis, since the histologic changesare not specific, the clinician should consider thepossibility of beryllium exposure, obtain an occupationalhistory, and document sensitization to beryllium byperforming a beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test onblood or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.103 Exposure toberyllium occurs in occupations that generate berylliumdust, such as primary production of beryllium, metalmachining, and reclaiming of scrap alloys; cases have alsobeen documented for individuals living near berylliumfacilities.104 Since the diagnosis needs clinical and labora-tory input, the main role of the pathologist is identificationof nonnecrotizing granulomas.

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is a type IV hypersensi-tivity reaction of the lung to inhaled organic antigens suchas proteins in bird feathers or thermophilic bacteria inmoldy hay. The term hypersensitivity (or the wordallergic in the British equivalent extrinsic allergic alveo-

litis) often conjures up images of eosinophils, but in facteosinophils are scant or absent105; rather, lymphocytes arethe predominant inflammatory cells in hypersensitivitypneumonitis. Plasma cells are also often present. Thepathologic findings of hypersensitivity pneumonitis areinterstitial (alveolar septal) chronic inflammation withperibronchiolar accentuation, poorly formed interstitialgranulomas, and foci of organizing pneumonia.106,107 Thishistologic triad is sufficiently characteristic that thepathologist can suggest the diagnosis solely on the basisof microscopic examination. Interstitial chronic inflam-mation is the most consistent finding and usuallydominates the histologic picture (Figure 5, C). It is oftenaccentuated around bronchioles and may be associated

with acute or chronic bronchiolitis. Small, poorly formedgranulomas or multinucleated giant cells are randomlyscattered within the interstitial inflammation and/orbronchiolar walls. The granulomas can be small anddifficult to identify and often consist of only a few looselyaggregated histiocytes108 (Figure 5, D). In some cases,there are only rare multinucleated giant cells in theinterstitium without frank granulomas (Figure 6, C andD). Cytoplasmic inclusions (such as asteroid bodies,Schaumann bodies, or cholesterol clefts) are often prom-inent within granulomas or multinucleated giant cells(Figure 6, C and D). They represent products of macro-phage metabolism (endogenous) and must not be con-fused with foreign material (exogenous) (Figure 6, G andH). The occasional birefringence of the endogenousinclusions seen in hypersensitivity pneumonitis can alsolead to misinterpretation as foreign material. Foamymacrophages often accumulate within alveolar spaces inhypersensitivity pneumonitis and are a manifestation ofbronchiolar obstruction.

The presence of nonnecrotizing granulomas can raisethe possibility of sarcoidosis. In contrast to hypersensitiv-ity pneumonitis, sarcoid granulomas are well formed and

r

(exogenous) surrounded by multinucleated giant cells. Same case as G. Such structures can be more difficult to recognize than intact vegetable

particles (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnifications3

400 [AH]; hematoxylin-eosin, polarized light, original magnifications3

400 [insets Band F]).

Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal 681

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

16/24

have a lymphangitic distribution. Moreover, the lungaway from the granulomas in sarcoidosis is normal, whilein hypersensitivity pneumonitis there is significant inter-stitial inflammation even in areas where no granulomasare present (Figure 5, A through D). Granulomatousvasculitis may be present in sarcoidosis but not inhypersensitivity pneumonitis. Finally, small foci of orga-nizing pneumonia are common in hypersensitivity pneu-monitis but not in sarcoidosis.

Differentiation from hot tub lung (a hypersensitivitypneumonitis-like disease; see below) is more difficult andmay be impossible on histologic grounds. Many of themorphologic features of hypersensitivity pneumonitis andhot tub lung overlap, including mixed interstitial and airspace involvement, interstitial chronic inflammation, andorganizing pneumonia. In classic cases, however, hot tublung is characterized by fairly large, well-formed granu-lomas located predominantly within bronchiolar lumens,as opposed to the small, poorly formed interstitialgranulomas of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (Figure 5, Cthrough F). In difficult cases, a final determination of thediagnosis may require a clinical history of hot tub use and

identification of mycobacterial organisms (hot tub lung) ora history of other antigenic exposure such as birds or amoldy home (for hypersensitivity pneumonitis). Bothconditions may resolve with cessation of exposure to thecausative agent.

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia can be difficult todifferentiate from hypersensitivity pneumonitis because itfeatures an interstitial lymphoid infiltrate with looselyformed granulomas. The findings that differentiate lym-phoid interstitial pneumonia from hypersensitivity pneu-monitis include lack of peribronchiolar accentuation andorganizing pneumonia and the frequent presence of anunderlying condition such as Sjogren syndrome or humanimmunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Finally, hyper-sensitivity pneumonitis also needs to be differentiatedfrom other, nongranulomatous causes of chronic intersti-tial inflammation such as nonspecific interstitial pneumo-nia or usual interstitial pneumonia.

Hot Tub Lung

Hot tub lung is a recently described entity characterizedby a hypersensitivity pneumonitis-like response to non-tuberculous mycobacteria (specifically, Mycobacteriumavium complex, abbreviated as MAC) inhaled in aerosolform from hot tubs.39,109124 Hot tubs provide an idealtemperature for the growth of the organisms and a meansfor their aerosolization. However, since other sources like

shower heads and therapy pools potentially providesimilar conditions,125 the more inclusive term MAChypersensitivitylike disease has been used.39 M aviumcomplex organisms are cultured from the sputum, lungtissue, and/or hot tubs in most, but not all, cases. Optimaltreatment (cessation of hot tub use and/or corticosteroidor anti-mycobacterial therapy) is unclear, but there isexpert consensus that patients should completely avoidreexposure to indoor hot tubs.39 The condition resolves inmost patients regardless of the treatment modality.

The most characteristic pathologic finding of hot tublung is the presence of granulomas within air spaces(usually the lumens of small bronchioles) (Figure 5, E and

F). All other findings are variable: the granulomas mayalso be located randomly within alveolar spaces or

bronchiolar walls, are usually nonnecrotizing but necro-tizing granulomas are occasionally present, and are betterdefined than those seen in hypersensitivity pneumonitisbut not as well formed as those of sarcoidosis. Organizingpneumonia is often present. Mycobacteria may or may notbe identifiable with acid-fast stains. Interstitial inflamma-tion may be present but is variable in extent. Definitivediagnosis requires a history of hot tub use or, more rarely,exposure to aerosolized water contaminated with myco-bacterial organisms.122,125 In summary, hot tub lung can besuspected, but not definitively diagnosed, solely on thebasis of histologic findings.

The main differential diagnostic considerations (Fig-ure 5, A through F) are hypersensitivity pneumonitis (dueto causes other than MAC), MAC infection (in patientswithout hot tubs), and sarcoidosis. The differentialdiagnosis with hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to othercauses is discussed in the section on the latter entity. Mavium complex infection in patients without hot tubs maycause an organizing granulomatous pneumonia. Acid-fastorganisms may be present (or absent) in both entities. Inthe absence of a history of hot tub use, therefore, it is

impossible to differentiate hot tub lung and MACinfection. Sarcoidosis is easier to distinguish from hottub lung: it is characterized by better-defined, exclusivelyinterstitial granulomas, a lymphangitic distribution, andgranulomatous vasculitis, none of which are features ofhot tub lung. Features that favor hot tub lung oversarcoidosis include identification of mycobacteria, airspace granulomas, interstitial inflammation away fromthe granulomas, and organizing pneumonia.

Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) is an uncommonform of interstitial lung disease, usually diagnosed in thesetting of human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, Sjogrensyndrome, or other diseases involving immune dysregu-lation.126128 Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia is notusually considered a granulomatous disease, but it ismentioned here because small granulomas are commonlypart of the histologic picture. Histologically, LIP ischaracterized by dense and diffuse alveolar septal(interstitial) lymphoplasmacytic chronic inflammationand scattered histiocytes. Germinal centers may beprominent. Small, loosely formed, nonnecrotizing granu-lomas are often present.4,129 Immunohistochemical stainsshow that the inflammatory infiltrate contains more Tlymphocytes than B lymphocytes. Gene rearrangementstudies demonstrate that the B lymphocytes are polyclon-

al.128

The differential diagnosis includes hypersensitivitypneumonitis and low-grade B-cell lymphomas of extra-nodal marginal zone/mucosa-associated lymphoid tissuetype, both of which may be associated with poorly formedgranulomas. The main histologic features differentiatingLIP from hypersensitivity pneumonitis are the greaterdensity of the alveolar septal infiltrate and the presence ofgerminal centers in LIP versus peribronchiolar accentua-tion of interstitial inflammation and foci of organizingpneumonia in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Lymphoidinterstitial pneumonia must also be differentiated fromlow-grade B-cell lymphomas. The predominance of T cells

over B cells, polyclonality of the B cells, and the absence ofa lymphangitic distribution are features that favor LIP.

682 Arch Pathol Lab MedVol 134, May 2010 Granulomatous Lung DiseaseMukhopadhyay & Gal

-

7/29/2019 Granulomatous Lung Desease

17/24

Wegener Granulomatosis

Ideally, Wegener granulomatosis is diagnosed inpatients with upper respiratory tract symptoms, multifo-cal lung involvement, kidney disease,130 anti-neutrophilcytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA),131 and necrotizing gran-ulomas with necrotizing vasculitis. However, this is notalways the case in practice. Renal involvement may beabsent at presentation,130,132 the clinical features may

overlap with infectious diseases, disease may be limitedto the lungs,133137 and the lung lesions may be solitary.134

Test findings with ANCA may be negative130,131,137,138 orfalsely positive.139 Cases sent for biopsy are often thosewith atypical clinical features and not infrequently haveatypical pathologic presentations. From the surgicalpathologists perspective, relevant clinical history andresults of ANCA testing are often unavailable at the timeof biopsy.137 The role of pathologic examination is crucialin such cases and often helps the clinician to initiatetherapy in a timely fashion. When classic histologicfeatures are present, Wegener granulomatosis can bediagnosed even in an unusual clinical setting.134

On the other hand, if histologic findings are not classic,

clinical input and ANCA results assume greater impor-tance138; cases without necrotizing vasculitis, in particular,should not be diagnosed as Wegener granulomatosis onthe basis of pathologic findings alone. In the appropriatesetting, the diagnosis can occasionally be made withtransbronchial biopsies.140

The classic histologic picture of Wegener granulomato-sis consists of necrotizing granulomatous inflammationaccompanied by necrotizing vasculitis4,135,136 (Figure 7, A,C, and E). The granulomas are suppurative (neutrophil-rich) and resemble abscesses at low magnification(Figure 7, A). The necrotic (suppurative) areas are usuallyirregular in contour, with a deeply basophilic, dirty

appearance owing to the presence of neutrophils andnuclear debris (Figure 7, C). Palisading histiocytes, acuteand chronic inflammation, and granulation tissue sur-round the suppurative necrosis. Multinucleated giantcells, when present, are distinctive but not pathognomonicfor Wegener granulomatosis. They stand out at lowmagnification because of the presence of multiple, closelypacked, hyperchromatic nuclei.137 In contrast, compact,sarcoidlike, nonnecrotizing granulomas are exceptionalin Wegener granulomatosis. Eosinophils may be absent orpresent in small numbers; only rarely are they numer-ous.4,132,136,138,141 Hilar lymph nodes do not show granulo-mas.

Necrotizing vasculitis is the single most important

feature in the histologic diagnosis of Wegener granulo-matosis but has been poorly defined in the literature.Several points must be stressed regarding its identifica-tion.

1. Necrotizing vasculitis can sometimes be very difficultto identify because the affected vessels may becompletely necrotic. Since neutrophils in Wegenergranulomatosis are commonly necrotic and karyor-rhectic, the presence of necrotic neutrophils in thevessel wall is an acceptable surrogate for necrosis ofthe wall itself. Thus, the vessel-destructive vascularinfiltrate that defines necrotizing vasculitis may consistof necrotic neutrophils,4 a mixture of necrotic neutro-phils and histiocytes (Figure 7, E), suppurative necro-

sis,132 suppurative granulomas,136 or fibrinoid necro-sis.132,142

2. Although a vasculitis comprising lymphocytes or a mix-ture of lymphocytes and histiocytes is very common inWegener granulomatosis,132,136 this finding by itself doesnot constitute necrotizing vasculitis. This type ofnonnecrotizing vasculitis is common in infectious gran-ulomas10 (Figure 7, F). Granulomatous vasculitis with-

out necrosis is also common in sarcoidosis.36,98

3. Necrotizing vasculitis is usually found within the in-flamed, but nonnecrotic area in the lesion, and this iswhere it should be sought. Vasculitis, necrotizing orotherwise, is uncommon in the normal lung surround-ing the inflamed area.10,136,142 Within the inflamed area,it is important to identify necrotizing vasculitis inviable parenchyma. Such viable areas are locatedadjacent to, but not within, the necrosis. Completelynecrotic vessels within areas of parenchymal necrosisdo not constitute acceptable evidence of necrotizingvasculitis,4 since it is impossible to determine if theyare merely included in the necrosis as innocent

bystanders.4. Necrotizing vasculitis is most readily identified when

it is eccentric, affecting the vessel focally and leavingthe rest of the wall uninvolved.4,134,137,142 Since theaffected vessel is not completely necrotic, recognitionof necrotizing vasculitis is facilitated. This type ofinvolvement is common in Wegener granulomatosis.

5. Vasculitis in Wegener granulomatosis affects both ar-teries and veins; occasionally, capillaries may beinvolved in a process known as necrotizing capillar-itis132,138,143145 (see below). Necrotizing capillaritis re-sults in intra-alveolar hemorrhage, which may bemassive and potentially fatal.

Other histologic features that may be present inWegener granulomatosis include small microabscesses,small suppurative granulomas, necrosis of collagen, andorganizing pneumonia at the periphery of the main lesion.

Several uncommon histologic variants of Wegenergranulomatosis have been described. These are character-ized by unusual prominence of 1 histologic feature, oftenat the expense of the other classic features describedabove. These include the bronchocentric variant,146 bron-chiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonialike variant,137

eosinophilic variant,141 and the alveolar hemorrhage andcapillaritis variant.134,144,145,147

The main differential diagnosis is with infections,134