Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay, Unalaska Island: Spatial...

Transcript of Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay, Unalaska Island: Spatial...

Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island Spatial and

Temporal PatternsBarbara E Bundy Allen P McCartney and Douglas W Veltre

Abstract Unalaska History and Archaeology Project researchers excavated several thousandglass trade beads from an Aleutian longhouse at the Reese Bay site on Unalaska Island AlaskaThis paper provides a description of the beads a discussion of their use by Russian explorersand Alaska Natives and an analysis of the horizontal and vertical distribution of the beadswithin the longhouse Comparison to other Alaskan sites revealed that the composition of theReese Bay trade bead assemblage is consistent with occupation during the early Russian periodSeveral factors both behavioral and depositional created and affected the spatial patterning ofthe beads within the site roof fall from the dismantling of the longhouse superstructure peri-odic housecleaning by the residents of the longhouse bead working techniques and locationpreferences and changing status relationships within the longhouse The spatial and temporalpatterning of the glass trade beads from the Reese Bay site provides insight into the lives of theinhabitants

IntroductionBy the middle of the eighteenth century Imper-ial Russiarsquos search for fur led to the shores of theNew World In 1741 Aleksei Chirikov second-in-command of the Bering expedition returnedto the Russian mainland with hundreds of peltsincluding 900 sea otter skins (Berkh 19741) His cargo touched off a Russian ldquofur rushrdquo toAlaska that ran from 1743 until the sale ofAlaska by Russia to the United States in 1867(Gibson 1976viii) The occupation of Alaska began in the Aleutians and moved steadily eastward It was generally characterized by hos-

tility toward Native groups although contact situations also included intermarriage and mutually beneficial trade relationships (Gibson19768)

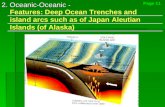

This paper examines the early Russian con-tact period through a case study of the glasstrade beads recovered from the Reese Bay archaeological site on Unalaska Island in theeastern Aleutian Islands (Fig 1) The bay is located on the north end of the island northwestof Unalaska Bay The Reese Bay site (UNL-063Fig 2) is situated on a spit formed 3000ndash5000years ago (McCartney et al 1988) and consists oftwo large multi-family longhouses from the early

Barbara E Bundy Department of Anthropology University of Oregon Eugene Oregon 97403

Allen P McCartney Department of Anthropology University of Arkansas Fayetteville Arkansas 72701

Douglas W Veltre Department of Anthropology University of AlaskaAnchorage Alaska 99508

ARCTIC ANTHROPOLOGY Vol 40 No 1 pp 29ndash47 2003 ISSN 0066-6939copy 2003 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 29

contact period an older midden and smallerhouses of an indeterminate period (McCartneyand Veltre in press Veltre and McCartney 2001)Longhouse 2 was tested in 1986 and partially excavated in the late 1980s by the Unalaska His-tory and Archaeology Project (McCartney et al1988 1990)

More than 2000 glass trade beads were re-covered from the longhouse excavation Thisbead collection is used to consider differentquestions about the community at Reese BayFirst the occupation of the site in historic timescan be dated by seriating the beads a techniquesuccessfully applied in other areas of Alaska(Crowell 1994) Second the distribution of thebeads within the site may reflect Native socialstructure during the early Russian contact pe-riod especially in terms of gender and statusUnderstanding changes in bead use through time provides insight into how Alaska Nativecommunities adapted to both the stresses andthe opportunities of Russian contact With thosegoals in mind the ethnohistorical documenta-tion of the glass bead trade in the early Russianperiod is reviewed and the composition anddistribution of the Reese Bay trade bead assem-blage is compared to historically reported pat-terns of bead use

Trade Beads and Historical Archaeology

Russian traders and explorers left few descriptionsof traditional Unangan and Eskimo cultures as theyexisted at the time of contact although by the nine-teenth century a few clergymen were writing de-tailed accounts (Black 1988) The accounts likemany colonial documents are difficult to interpretEven with the best of intentions first-time observersof a culture can easily form misconceptions that arereflected in text and illustrations a process Grumet(19957) called ldquocreative misunderstandingrdquo It fallsto archaeologists to clarify the history of this impor-tant era of upheaval and culture change

Archaeological data have much to offer in thesearch for a balanced history of the European oc-cupation of North America Trade bead analysiscan clarify a number of theoretical issues for sev-eral reasons Beads have played an important rolein European trade with local groups all over theworld This ubiquity provides an excellent basefor comparing European and Native American re-lations at different times and places Also glasstrade beads can be ldquoa reliable dating indexrdquo if ar-chaeological and ethnohistorical sources are com-bined (Spector 197617) Woodward (1965) notedthat trade bead preferences among Native groups

30 Arctic Anthropology 401

Figure 1 Unalaska Island (north portion) showing location of Reese Bay site

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 30

often changed quickly making time-definitionrather precise In fact trade beads have been suc-cessfully used as diagnostic artifacts for determin-ing dates of occupation and sources of trade goods(eg Crowell 1994 Mitchem and Leader 1988) Fi-nally beads often functioned differently in Euro-pean economies than in Native economies Therole of beads (and other ornaments) has often beenlikened to that of coin money in a traditionalWestern market system because they are ldquoroughlycommensurable and highly portablerdquo (Graeber19964) Their use by Native groups however wasprobably also influenced by the importance of sta-tus rules preferences regarding ornamentationand perhaps the individual history of the beadedobjects (Woodward 196518) All of these consider-ations dictated the value of the beads and the uni-verse of possibilities for their distribution (Graeber1996) Finally beads are easily lost mitigating theeffects of curation of artifacts during site use and

abandonment Given these qualities it should bepossible to discuss spatial patterning of beads withreference to social and economic structure in rap-idly changing and adapting societies

Glass trade bead studies have been ap-proached in many different ways depending onthe research goals of the project Typical interestsare dating site occupation determining the man-ufacturing origin of the beads understanding theavailability of beads and the preferences of beadconsumers discussing the use of beads duringsite occupation and inferring the causes of beadloss and disposal (Francis 1994) Bead use andloss patterns reflect consumer preferences beadavailability and other rules of ownership and or-namentation Archaeological patterning may alsobe the result of beaded-item manufacture and re-lated issues like the availability of beading materi-als (eg fine needles thread) and visibilitySpector (1976) suggested that bead researchers

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 31

Figure 2 The Reese Bay site (UNL-063) from McCartney et al (19885)

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 31

use both ethnohistorical and archaeological datato accurately classify and describe beads and tounderstand how they were perceived and used byNative and European groups

The Aleutian IslandsClimate and GeographyThe Aleutian Islands begin with Unimak Islandjust west of the Alaska Peninsula and extend about1100 miles to Attu Island The windswept islandsare home to a diverse marine environment (Pielou1991130) Sea otters sea lions and hair seals arepresent year-round as are many intertidal shell-fish species due to the absence of winter ice(Murie 1959) Whales fur seals migratory birdssalmon and plant foods are available seasonally(Laughlin and Aigner 1975) Halibut and cod arepresent year round but are more easily obtainedduring certain seasons when they move inshoreThe many bays and inlets that mark the shores ofthe islands increase the amount of coastline avail-able and provide sheltered landings for both hu-mans and their prey (McCartney 1984) Althoughit appears inhospitable the Aleutian environmenthas provided sufficient resources to maintain a hu-man community for over 8000 years (McCartney1984 McCartney and Veltre 1999)

The Unangan PeopleMost of the historical information about Unanganculture during the second half of the eighteenthcentury comes from reports given by seafarers andImperial employees to the Russian government(Liapunova 1996133) It was not until the firsthalf of the nineteenth century that Bishop I Veni-aminov ([1840] 1984) made the first effort to com-prehensively document Unangan life (Liapunova199631) Several researchers have gleaned the fol-lowing description of early contact-era Unanganculture from early reports Veniaminovrsquos worksand archaeological data

The Aleutian cultural tradition at the time ofEuropean contact and long before was character-ized by a very effective focus on marine resources(Laughlin 1980 McCartney 1984) Seals whalesotters and occasionally walrus were hunted at sea(Liapunova 199689) Although Russians claimedthat ldquothe love of the Aleut for catching sea otterssurpasses any descriptionrdquo (Russian Naval Officerquoted in Gibson 19768) Laughlin (198042) sug-gested that the animals were infrequently huntedprior to Russian demands for their pelts Youngboys trained rigorously to perfect their endurance

and hunting techniques and Europeans nevermatched the efficiency and skill of Unangan seamammal hunters (Laughlin 198029 44) Othermarine resources like fish birds and shellfishwere also collected (Jochelson 193351 Lantis1984) Plentiful resources and wet weather en-sured that ldquonot much food was stored except forthe festivalsrdquo (Lantis 1984176)

Unangan socio-political organization at thetime of Russian contact resembled that of othernorthern coastal groups including Alutiiq andTlingit (Lantis 1984) Like the Tlingit Unangan so-ciety was divided into three groups elites com-moners and slaves (Liapunova 1996138ndash139)The elite group consisted of toions (chiefs) actingas household heads and their direct descendantsA toion oversaw kin-controlled hunting groundsand enforced behavioral norms but ldquoit may be thatkin membership was separate from inheritance ofoffice or privileged positionrdquo (Lantis 1984176)Laughlin (198058ndash59) noted that household headswere also expected to be unusually strong and suc-cessful hunters Thus while status was indicatedby descent it was not ensured

Eastern Aleutian Islanders lived in semi-subterranean longhouses that Russians calledbarabari or yurts (Laughlin 198050 McCartneyand Veltre in press) A longhouse contained sev-eral families who were related in a variety of waysin that ldquorules of residence did not seem to bestrictly enforcedrdquo (Lantis 1984176) Veniaminov([1840] 1984) reported that residence within thelonghouse was determined by status with thehighest-status individuals living at the east endand others continuing in descending order Nu-clear families had living and sleeping space alongthe walls of the structure and side rooms wereused for storage or additional living space (Veni-aminov [1840] 1984262) Assessments of howmany people lived in a single longhouse vary but afairly conservative estimate might be 40 residents(Laughlin 198050)

Unangan life was patterned not only by thedemanding environment but also by strong cul-tural traditions Understanding how these tradi-tions changed as Unangan people adapted toRussian contact is central to historical archaeologyand ethnohistory in the Islands

Russian AmericaRussian actions in the New World were deter-mined by economic goals and restrictions envi-ronmental constraints religious convictions andthe cultural traditions of Russian and Native

32 Arctic Anthropology 401

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 32

groups These factors make the history of theAleutian Islands after Russian contact unique inmany respects but also similar to other contact sit-uations During the eighteenth century the fu-ture of any European country rested on itscolonial possessions Strongly centralizedmonarchies competed for control of lucrativenew territories in the hopes that the exploitationof new lands would lead the colonial power to astrong position in the European economy (Pag-den 199566ndash67) Russia long dismissed as aneconomic backwater was especially eager to be-come a major financial force in Europe(Dmytryshyn et al 1988) The high demand inthe West for furmdashldquosoft goldrdquomdashprovided the op-portunity the Russian government sought

Alaska however was problematic for Rus-sian fortune-seekers Russian sailors often inmakeshift vessels were ill-prepared for the violentstorms and winter ice of the Bering Sea(Dmytryshyn et al 1988xl Makarova 197538)Transportation in the new colony also proved dif-ficult and Native resistance in some areas wasfierce Provisioning of explorers and later settlerswas a constant problem (Gibson 1990) By the1770s Russians also faced competition from theEnglish French and Spanish in the New World asituation that became a drain on already scarce re-sources (Gibson 1990) Despite these daunting ob-stacles many Russians found the lure of Alaskairresistible As the trickle of Russian merchantvoyages and government-sponsored expeditionsbecame a flood Alaskan Natives were forced toadopt a variety of survival strategies

Native-Russian Relations in the Early Contact PeriodUnangan resistance violent and non-violent iswell documented throughout the Russian occupa-tion (eg Berkh 197433ndash34 Dmytryshyn et al1988) It is likely that the Unangan people werequickly subjugated by Russian demands due totheir isolation as well as lack of access to firearms(Dmytryshyn et al 1988)

Russian Imperial policy ostensibly encour-aged even demanded friendly relations with in-digenous people A report by a Siberian officialauthorizing Ivan Bechevinrsquos 1760 voyage clearlystates that any crewman ldquois to be obligated underpenalty of death not to cause any harm or eventhe slightest resentment among the inhabitants ofthe island who are iasak [tribute-paying] subjectsrdquo(as quoted in Dmytryshyn 1988204) However itwas reported in 1776 that Bechevinrsquos men ldquocom-

mitted indescribable abuses ruin and murderupon the natives there [the Aleutians]rdquo (Zubov inBerkh 197428) Government agents were sent tothe colonies to investigate reports of abuse on sev-eral occasions as the Imperial Government strug-gled to control the fur trade in the 1780s(Dmytryshyn 1988) However practices and atti-tudes supported by the government hindered theachievement of that goal Until 1788 the Russiangovernment required that inhabitants of landclaimed by the government pay iasak usually infurs (Gibson 196931) Voyagers were required tokeep records of tribute paid and upon their returnto Russia these ldquoiasak booksrdquo were scrutinized(Dmytryshyn et al 1988) This practice must haveencouraged promyshlenniki [Russian fur-huntingsailors] to collect tribute by whatever means nec-essary Although the practice of giving giftsmdashoftentrade beadsmdashin return for iasak was fairly com-mon the gifts were specifically meant to create afeeling of indebtedness that encouraged paymentin the future (Khlebnikov 1994240) There wasalso significant pressure from the government andprivate companies for expeditions to return withmany furs which contributed to forced labor andother mistreatments

Additionally Russian officials regularly re-ferred to Native inhabitants as savages and hea-thens (as quoted in Dmytryshyn 1988) Gifts givenas trade goods or in exchange for iasak were con-sidered trinkets and worthless baubles proof thatNative people were unable to judge true value Thisperception of superiority surely encouraged and ex-cused abuses by Russian promyshlenniki Thus al-though the Imperial Government nominallydiscouraged mistreatment of Alaska Natives andSiberians its own social philosophy and economicpolicies exacerbated the problem (Bundy 1998)

Thoughtlessness misunderstandings andoutright cruelty on the part of the Russians led tothe rapid depopulation of the Aleutians Manyhunters were killed on forced sea mammal huntsIn the last decade of the eighteenth century somewere taken to other Russian-held areas never to re-turn to their families (von Langsdorff 199313ndash14)Also those who remained were forced to focustheir efforts on obtaining sea otter pelts to the ex-clusion of important food sources (Dmytryshyn etal 1988) The absence of hunters led to food short-ages in Native communities food poisoning fromeating rotten beached carcasses (Dmytryshyn et al1988) and a shift in the subsistence economy to fo-cus on ldquoresources obtainable without their malehunters presentrdquo (Veltre 1990179) Diseases intro-duced by Europeans also contributed to population

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 33

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 33

loss and weakened survivors Population decreaseas well as the Russian desire to consolidate settle-ments within reach of their insufficient staff led tothe resettlement of entire villages (Veltre 1990)

European interference in Native Americansettlements often led to unforeseen social disrup-tion (eg Rollings 1992154) Europeans (includ-ing Russians) preferred to identify one man as thesole leader of a community and favored him intrade and political dealings In Russian Americasingle men were encouraged to marry Nativewomen allowing those women greater access toEuropean goods These two practices created aclass of high-status men and women who acted asldquomiddlemen or brokers between the two cul-turesrdquo (Veltre 1990180) The trade goods accumu-lated by these middlemen may be found in thehigh-status portions of Native longhouses as wellas in Russian dwellings

Changes made to settlement patterns duringthe Russian period altered the issue of status andresidence Christian beliefs favored the Europeanstyle single-family unit over household-based orpolygamous arrangements (Veltre 1990) Veni-aminov ([1840] 1984264) wrote that in 1805 theRussian-American Company employee Rezanov or-dered that Unalaskans build above ground single-family dwellings effectively ending communallonghouse use Together with severe populationreduction this significantly changed settlementpatterns The upheaval in Unangan life caused byRussian occupation was present very early in thecontact period and surely impacted communitieslike the Reese Bay village

The Chronology of Contact in the Unalaska AreaUnalaska Island is mentioned in many early Rus-sian accounts and Reese Bay itself in a few ofthose (McCartney et al 1988) Russia claimed Un-alaska Island in 1753 when Bashmakov ldquodiscov-eredrdquo the region (Berkh 197414ndash15) but the firstcontacts with inhabitants were not reported untilat least 1758 (Black 1991) A history of early con-tacts is provided by Black (Black 1991 Black andLiapunova 1988 McCartney et al 1988) and issummarized here Stepan Glotov made the firstrecorded contact in 1761mdashalthough there mayhave been earlier Russian landings on the islandGlotov apparently enjoyed ldquoamicable relationsand trade until his departure in May 1762rdquo (Mc-Cartney et al 198834) In 1763 however thecrews of the Sv Gavriil and the Sv Vladimir dis-

carded this peaceful precedent The behavior ofthe men which included beating rape kidnap-ping and murder later prompted an Imperial ju-diciary investigation The brutality of thisincident elicited an organized military responsefrom Unangan people on Umnak Unalaska andUnimak islands It is unclear if such a large al-liance was a departure from previous precontactpolitical interactions

The first specific mentions of the Reese Baysite in Russian writings occurred between 1763and 1766 when six different Russian vessels vis-ited Unalaska Island After this date the degree ofRussian-Unangan interaction is difficult to ascer-tain McCartney et al (199023) note that there wasldquoa differential concentration of Russian shippingin specific areas of the Aleutian archipelago andaround certain favored harborsrdquo Reese Bay wasapparently not one of these harbors Althoughthere is some mention of a trading post at neigh-boring Captains Harbor by the mid-1770s (Gibson19765) it is unclear how much contact the ReeseBay villagers had with a frequented port or perma-nent settlement

Between 1763 and 1764 there were severalarmed conflicts between Russians and Unanganpeople Inhabitants of Reese Bay (calledVeselovskoe settlement by Veniaminov [198493])are named specifically in these accounts In oneincident in 1765 19 Reese Bay villagers werekilled in a conflict with Solovrsquoev (Black 1991) Na-tive military resistance was unsuccessful in thelong run and by the time of Captain James Cookrsquosvisit to the Aleutians in 1778 Russians were inter-acting with Native communities on almost all theislands Thus during the early period of Russianoccupation Native-Russian relations varied fromfairly amiable trade to outright warfare

Billings estimated the population of theReese Bay village in the 1780s to consist of about30 adult males and their dependents a number al-ready diminished from the first estimates (Titova1980) According to Veniaminovrsquos estimate ([1840]1984) by 1824 only 15 people were living at thesite Von Langsdorff (199313ndash14) and other ob-servers attribute the rapid population decrease inthe Aleutian Islands in general to great losses ofmen in forced hunts for sea mammals and stressfulliving conditions for the remaining villagers Ac-curate dating of the site is essential in reconcilinghistorical accounts and the archaeological recordIn this tumultuous era the presence and distribu-tion of trade goods are significant Trade goods donot just indicate acculturation in the form of the

34 Arctic Anthropology 401

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 34

gradual adoption of a market economy rather thedistribution of non-local items was the end prod-uct of a multifaceted relationship

Glass Trade Beads in the AleutiansThree aspects of trade bead research are relevantto the study of social reorganization in the Aleu-tians manufacture and typology historic reportsof use and frequency and distribution in archaeol-ogy sites To address these topics we establish aconsistent descriptive typology and examine thehistorical bead trade before discussing frequencyand distribution

Bead Nomenclature Typology and ManufactureFrom the earliest archaeological reports of tradebeads to the present typology has been problem-atic Beads are named in several different waysand nomenclature is generally not consistent overtime and across regions (Sprague 1985) Localizedmanufacturers and traders had their own systemsof classification based on size andor manufactur-ing technique and ldquothe collector of beads in ourown times has added to the confusion by callingbeads by local terms which outside that area havelittle or no meaningrdquo (Woodward 19654) Early at-tempts at bead terminology tended to be broadlydescriptive rather than exact but by the 1970s sev-eral objective classification systems had been pro-posed (eg Karklins 1982 Kidd and Kidd 1970Stone 1970) These typologies are based on ldquofor-mal physical properties of glass beads which re-flect manufacturing processesrdquo (Spector 197620)

There is no hierarchy or value assessment implicitin the language and indeed most of the typologiesuse letters and numbers to represent bead typesHowever more recent studies use both descriptivelanguage and a type number for more detailed ref-erence (eg Crowell 1997) a precedent that willbe followed here The 2266 Reese Bay beads ana-lyzed here were coded by Scott (1990) followingthe Kidd and Kidd (1970) system

Bead color description has been challengingfor archaeologists Even in similar beads colormay vary because ldquothe purity of the coloringchemicals was not well controlledrdquo (Spector197622) Recently several bead researchers haveadvocated using Inter-Society Color Council Na-tional Bureau of Standards (ISCC-NBS) Color Cen-troid Charts (1955) which render colorscomparable even in text description Many of theReese Bay beads were assigned Centroid ColorChart numbers by Scott (1990) These standardiza-tions make the Reese Bay data comparable to thosefrom other sites in southern Alaska (Table 1)

Several researchers have discussed at lengthmanufacturing processes and the related nomen-clature (Kidd 1979 van der Sleen 1973 Wood-ward 1965) The techniques relevant to the ReeseBay beads will be summarized here to define theterms used in bead descriptions There is an essen-tial division between drawn (hollow-cane) beadsand wire-wound (mandrel) beads Drawn beadswere cut from a long thin tube of glass (the hollowcane) The glass was drawn out of a furnace on arod and shaped while still molten The cane wasformed by introducing a bubble to a mass ofmolten glass in which two rods have been in-serted At this point the original glass may have

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 35

Table 1 Reese Bay bead colors and the associated Centroid Chart numbers

Associated ISCC-NBS Color Centroid Number in Reese BayColor Group Chart Numbers Bead Collection

White 263 92 (yellowish white one bead) 1199Light and Greenish Blues 168 169 171 172 173 175 180 748Reds 6 40 184Yellows 68 72 83 85 86 87 89 90 91 94 99 102 34Greens 136 137 141 144 145 146 162 30Dark and Purplish Blues 176 183 184 185 194 196 197 204 29Very Dark Burgundy (Appears 267 15Black)Ambers (Orange and Brown) 54 55 59 62 76 10Clear NA 10Undetermined or Multi-colored NA 7

Total 2266

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 35

been dipped in another color (or colors) of glass toform a multi-layered bead The cornaline drsquoAleppo(a red bead with a clear green or white center)common in Alaskan assemblages was manufac-tured in this way Two people then pulled the rodsapart often to considerable length The finishedcanes were laid on wooden racks to cool Oftenthe beads were polished and their sharp cornersrounded off by agitating them in hot sand Manu-facturers usually sorted drawn beads in sievesstrung them and sold them by size in bundles of12 (or more) strings

In the Kidd and Kidd system drawn beadsare divided by shape decoration and size Firstbeads that have been rounded are separated fromnon-rounded beads and multi-layered beads areseparated from single-layered resulting in fourgroups These are further subdivided by the exis-tence and type of surface decoration and then bythe overall shape of the bead

Wire-wound beads (sometimes called neck-lace beads) were produced quite differently A pre-made glass rod was heated over a fire until soft andthen wound around a stiff wire called a mandrelThe beads could be pressed into a mold or rolledalong an indented plate to form a pattern Color de-signs could be made by using rods of several colorsto form the bead or by ldquodrawingrdquo on the still-hotbead with thin lines of glass and possibly drawinga wire through those to make floral or other de-signs After several beads had been wrappedaround it the mandrel was set aside to cool Thebeads were then shaken from the mandrel Wire-wound beads required much more individual at-tention but because their manufacture did notrequire a furnace they could be produced by a cot-tage industry In the Chinese wire-wound bead in-dustry individuals bought glass rods from a factoryand then sold the finished beads back to the fac-tory for payment and more glass (Miller 199412)

Wound beads are much harder to classifythan drawn beads because they are made individu-ally and are ldquocapable of almost infinite variationrdquo(Kidd and Kidd 197049) However they are oftendivided into simple categories based on shape anddecoration Single-color undecorated beads areseparated from plain shaped beads and from dec-orated beads (which may or may not be shaped)Both shaped and shaped-and-decorated beads aresubdivided by appearance Kidd and Kidd (1970)offer color plates for both wound and drawn beadsthat represent further numbered divisions but theuse of color charts seems to have replaced this fi-nal classification

Almost all bead researchers agree that classi-fication systems are not an end in themselves butan analytical tool by which ldquocomparison of vari-ous assemblages will reveal cultural andor tempo-ral dynamicsrdquo (Spector 197620) There were twomain goals for the classification of the Reese Baybeads to ensure that the assemblage is standard-ized and comparable to other collections and toprovide a basis for comparing spatial and temporaldistribution of different types of beads within ahouse Historical references to different bead typesand the preferences of Russians and Alaska Na-tives make a logical starting point

Local Bead Names in AlaskaEuropeans in the Aleutian Islands make referenceto beads by several different names Russians mostoften use the terms bisera (singular biser) and korolrsquoki (singular korolek) which many believe re-fer to small drawn beads and larger wound beadsrespectively (Crowell 1997177) However thereare some apparent exceptions and inconsistenciesin different accounts It can be difficult to findsources in the original Russian but several transla-tors have used ldquoglass beadsrdquo for bisera andldquocoralsrdquo or ldquolarge beadsrdquo for korolrsquoki (eg Khleb-nikov 19944 56 122) The fact that korolrsquoki areoften listed by number (although occasionally by avolume measure) while bisera are listed by ameasuring unit (sazhen which refers to length ofthe string) suggests that korolrsquoki were larger(Anonymous 1988 [1789] Khlebnikov 1994240)There are exceptions to this interpretation as wellKhlebnikov (199456) noted that Alaska Nativestrading in Sitka ldquowillingly receive light blue and redbeads large blue and small clear green korolrsquoki rdquoindicating that some korolrsquoki are small beads

It is tempting to speculate that some excep-tions occur when the word korolrsquoki is used to des-ignate color instead of size or type much the sameas ldquoamberrdquo or ldquocoralrdquo in modern English In amodern Russian dictionary korral (coral) is de-fined not only as an oceanic species but also as ldquoabright-red pink or white stonerdquo (Ozhegov 1989)Korolek in the modern language refers to a type ofsmall bright-red bird or a round ingot of metal(Ozhegov 1989) However korolrsquoki are often iden-tified as transparent dark blue sky blue andgreen (Khlebnikov 199457) but apparently never(or rarely) as red or pink Thus the connectionwith color suggested by the modern words is notsupported by ethnohistorical descriptions Al-though Unangan people likely had their own

36 Arctic Anthropology 401

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 36

names for different bead types these have notbeen recorded

The Arrival of Beads in the AleutiansGlass trade beads as mentioned earlier are a goodchronological marker because styles change soquickly How and why bead assemblages changedin the last decades of the eighteenth century in theAleutians are crucial issues in assessing the mean-ing of the Reese Bay beads

Alaska Natives in Russian America acquiredbeads in several different ways Beads weresometimes given as gifts as Europeans often of-fered trade goods on meeting local inhabitants tosecure good relations Chirikov ([1741] quoted inDmytryshyn 1988144ndash145) instructed his crewmembers who were going ashore on a previouslyunknown Aleutian island and might encounterNatives to ldquoshow them friendship and give themsmall presentsrdquo because the Russians hoped togain information about the islands Later friend-ship gifts were used to facilitate trade Klichka([1779] quoted in Dmytryshyn 1988263) re-ported that the crew of the Sv Vladimir success-fully established friendly relations with theinhabitants of Unimak Island by givingldquoCherkassian tobacco various colored beadscopper kettles shirts and sealskinsrdquo Howeverthe promyshlenniki for the most part destroyedthose peaceful relations by using other tacticsdetrimental to Native communities to get whatthey wanted

Russians used gift giving with other coercivemeasures like hostage taking to force Native as-sistance Krenitsyn and Levashev [1771] observedthat in the Fox Islands promyshlenniki

try to take hostages children from that island ornearby islands If they cannot do this peacefullythey will use force Once this is done they issuetraps to the natives to use to take foxes They givethe natives seal and sea lion hides called lavtakswhich the natives use to cover their baidarkas andthey also give glass beads goat wool and small cop-per kettles The natives become so indebted to theRussians that all the while the Russians are on theisland the natives must provide them with fish andedible roots (quoted in Dmytryshyn 1988245)

Beads and other goods were also used to en-courage allegiance and loyalty to Russians and tosoften demands for tribute Khlebnikov (1994240)cited a document from Attu Island that records agift of ldquo 1 dagger 356 korolrsquoki [large beads] ofdifferent colorsmdash122 white 158 light blue 76light coloredmdashone funt red one-half funt light

blue one funt yellow and one-half funt greenbeads rdquo made to a local toion The documentadmonished the toion that he was ldquo com-manded to accept the items shown and orderedthat you should always be aware of the favor youhave receivedrdquo (Khlebnikov 1994240) EmpressAnna Ivanovna (quoted in Dmytryshyn 1988117)ordered explorers to give local inhabitants ldquosmallgifts in the name of Your Imperial Highness whenthey pay their iasakrdquo These offerings were morelike exchanges for other goods and services thangoodwill gifts

Outright trading of European goods in ex-change for furs was uncommon in the AleutiansUnangan people were compelled through hostage-taking and outright force to accept whatever wasproffered in return for furs Coxe (1780265) ob-served ldquo after obtaining from them [Unanganpeople] a certain quantity of furs by way of taxfor which they gave them quittances the Russianspay for the rest in beads false pearls goatrsquos woolcopper kettles hatchets ampcrdquo Payment was not al-ways satisfactory An unidentified Unalaska Na-tive ([1789] quoted in Dmytryshyn 1988369)complained to Russian government inspectors thatpromyshlenniki ldquo send us out to hunt againstour will and force us to provide food and do do-mestic work without pay From Cherepanovrsquos com-pany we receive in exchange for each sea otter pelteither a kettle shirt knife kerchief a tool to makearrows ten strings of coral or five six or ten to-bacco leaves and a handful of beadsrdquo Thus in theAleutians beads were initially given as gifts toforge ties or incur indebtedness but later wereforced upon islanders who were suffering more ba-sic needs

However the fact that beads were not consid-ered adequate compensation for goods and ser-vices does not mean that they were not valuedMany European reports note that Alaska Nativeseagerly sought beads in some circumstances espe-cially in the first decades after Russian contactDuring Glotovrsquos voyage in 1763 several Kodiak Is-landers ldquo offered to barter fox-skins for beadsThey did not set the least value upon other goodsof various kinds such as shirts linen and nan-keen but demanded glass beads of different sortsfor which they exchanged their skins with plea-surerdquo (Coxe 1780113ndash114) Cook found that in thePrince William Sound area ldquoa very great valuerdquowas set on large blue beads (Beaglehole19671418)

Aleutian Islanders similarly favored glassbeads and actively sought them for a time Some

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 37

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 37

types of beads had specific uses and were highlydesirable for that reason Francis (1988) noted thatbeads were a prestige item in the Aleutians Even-tually desire for tobacco iron alcohol and othergoods eclipsed demand for glass trade beads Beaduse likely also declined as traditional clothing andjewelry were replaced by European styles Anenormous number of beads however entered theAleutian Islands before declining in popularity Ingeneral beads were very common and were usedin a variety of ways

Glass Trade Bead Use by UnalaskansBead use existed in the Aleutians prior to Euro-pean contact Amber and Dentalium shell beadssmall carved bone or ivory figurines and birdbeaks were used as personal ornaments (Khleb-nikov 1994122 Krenitsyn and Levashev [1771] asquoted in Dmytryshyn 1988 von Langsdorff199316ndash17) Several European observers also re-ported the use of pebbles bone or ivory ldquocut liketeethrdquo (Coxe 1780257) which could refer tolabrets beads hung from them or both

Likewise glass trade beads were used mostlyfor personal ornamentation Unalaskan men deco-rated hunting hats with large blue wound beadsas described by many Europeans (eg Billings asquoted in Titova 1980201 Merck 198078) Menalso used beads in labrets and other jewelry ap-parently for feasting occasions Krenitsyn and Lev-ashev (quoted in Dmytryshyn 1988248) reportedthat ldquoin good times when they are engaged in fes-tivities they put beads and small bits of amber intheir ears and between the labrets in the lowerliprdquo Merck (198078) noted men wearing ldquoa ringof gut string through the cartilage of their noseSome glass garnets are strung on that ringrdquo Mendo not appear to have worn clothing decoratedwith beads or other ornaments

Unalaskan womenrsquos clothing on the otherhand was often heavily beaded with a combina-tion of small drawn beads and larger wound beads(Merck 198078) Sarychev (18068ndash9) noted thatldquothe front of the dress and the opening of thearms is trimmed with a row of pearls or coralTheir festival dress is similar in shape but moreenamelled and bordered with rows of coralsbirdrsquos beaks and goatrsquos hairrdquo

Thus it appears that the most decoratedclothing was saved for celebratory occasionsMerck (198079) also wrote that women wore moreelaborate parkas on such occasions The beadeddecoration on these parkas was reported to consist

of colored designs mostly blue on a white ground(Merck 198078) Women also used beads in jew-elry worn around the neck at the wrists and inlabrets earrings and nasal septum piercings (Coxe1780257 von Langsdorff 199317) Merck(198079) mentioned beads worn in a circular de-sign at the ears and hung from a piece of bone inthe nose Billings (in Titova 1980201) also re-ported women wearing ldquoa multitude of decora-tions two or three rows of such beads under theearsrdquo Women of common and slave ranks mayhave owned very little beaded clothing or none atall Francis (1994293) noted that ldquobeads could besocially valuablerdquo and an Unalaskan woman whoacquired a large number of beads ldquobecame an ob-ject of universal envy among her female country-women and was esteemed the richest of all theinhabitantsrdquo (Sarychev 180639) Overall theavailability of beads to Alaska-bound traders therelationship of Alaska Natives to Europeancolonists and Alaska Native tastes and needs in-fluenced the different types of beads that reachedthe Reese Bay longhouse

Glass Beads in the Reese Bay Longhouse

Original cultural processes post-depositional fac-tors and archaeological recovery techniques affectthe spatial and chronological distribution of thebeads The representativeness of the bead samplefrom the longhouse will be discussed before thepaper turns to the interpretation of the collection

Recovery Rates and Confounding FactorsThe complete Reese Bay bead assemblage consistsof approximately 3200 beads However due to in-complete records involving nearly 1000 of thebeads (important information concerning colorsize and type is missing) approximately one-thirdof the bead collection was excluded from thisanalysis These excluded beads are missing andare not currently available for examination andwhile there is provenience information availablefor these missing beads there is no descriptive in-formation The missing beads come from a varietyof spatial contexts and there does not appear to beany determining factor or pattern to the missinggroup Thus we suggest that the 2266 beads withcomplete records likely provide a representativesample of the whole The composition of the beadassemblage used in this analysismdashthe 2266beadsmdashis represented in Table 2

38 Arctic Anthropology 401

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 38

It is important to ascertain how recoveryrates affected the size and composition of the beadassemblage In 1988 1989 and 1990 the long-house was excavated in 1 m2 units and only thenorthwest quadrant (50 cm2) was water-screenedthrough 116Prime mesh One might expect that thenorthwest (water-screened) quadrant would pro-duce proportionally more small or dark beads thanwould the other three quadrants because recoveryof these difficult-to-see beads would be enhancedby the water-screening Small beads are definedhere as those less than 5 mm in diameter whilelarge beads are greater than 5 mm in diameterThis effectively distinguishes wound from drawn

beads as no wound bead was smaller than 5 mmand no drawn bead larger No beads smaller than 2mm in diameter were recovered from the ReeseBay longhouse

Figure 3 shows the distribution of beads inthe four quadrants Small beads were somewhatless likely to be found in non-water-screened unitsthan in units in the northwest quadrant but thedifference was not great Bead color was distrib-uted in very similar proportions across all quad-rants In other words the northwest quadrantcontained more beads of each color but not agreater variety or proportion of dark colored beadswith one exception No green beads were recovered

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 39

Table 2 Composition of the Reese Bay glass trade bead assemblage by bead type

Small Small Other LargeWhite Blue Cornaline Small Large Wound ampDrawn Drawn drsquoAleppo Drawn Wound Molded Total

NumberRecovered 1107 764 183 93 115 4 2266

Percentageof Total 489 337 81 41 49 02 100

red over green or clear small drawn type

Figure 3 Bead distribution by type and quadrant Northwest quadrants were waterscreened others were not

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 39

from non-water-screened quadrants but very fewgreen beads were recovered in general This maybe due to the rarity of green beads in the site ratherthan recovery methods Thus water screening ap-pears to improve bead recovery rates but not af-fect the sizes and colors of beads recovered

Nine-hundred forty-one beads were recov-ered from the northwest quadrant compared to348 386 and 364 from the northeast southwestand southeast quadrants respectively (for 222beads the quadrant was not recorded) Thus water-screening resulted in the recovery of almostthree times as many beads on average Even whenwater-screening was employed an unknown num-ber of beads were likely missed by excavatorsHowever it is encouraging that the proportions ofbead size and color are relatively constant acrossquadrants as this suggests that the Reese Bay col-lection is an adequate sample with which to makea detailed comparison of bead types

Post-depositional cultural activities mighthave affected the composition and patterning ofthe assemblage The superstructure of the long-house was probably dismantled and the majorsupports reused after abandonment (Mooney1993) Debris from this removal likely fell onto thehouse floor If activities had been conducted onthe roof prior to its removal artifacts on the roofwould have fallen onto the house floor during thedismantling process as well Finally periodichouse cleaning during occupation almost certainlyaffected artifact distribution With these caveats inmind the aspects of the bead assemblage of possi-ble cultural significance will be examined

Cultural Factors Assemblage CompositionEthnographic accounts describe a certain pattern ofbead use Based on these accounts bead color sizeand type are considered important variables Fur-ther descriptions of bead use lead to the expecta-tion that the small white drawn beads that wereused as background color on extensively decoratedwomenrsquos clothing would dominate the assemblageSmall colored drawn beads would be representedin somewhat lower numbers as would the largewound beads that were used more sparingly

The composition of the bead collection es-sentially fits the expected pattern White drawnbeads dominate the collection Together the smallwhite and blue drawn beads make up 826 of thetotal Only 5 of the beads were wound beadslarger than 50 mm in diameter which is consis-tent with historic accounts of bead trade and use

Cultural Factors Chronology and SeriationCrowell (1994 1997) used physical characteristicsof bead collections to develop a seriation chronol-ogy for the Alaskan bead trade part of which isshown in Figure 4 The 495 trade beads from the1986 testing were used to place Reese Bay in thechronology (Crowell 1994298) The Reese Baytrade bead proportions were however recalcu-lated using the entire bead collection Figure 5shows the 1986 data which were collected by Pe-ter Francis compared to the data from subsequentseasons The compositions of the assemblages arevery similar Even with the addition of more than2200 beads the proportions used by Crowell re-main essentially the same Crowellrsquos table suggeststhat an early assemblage would lack cornalinedrsquoAleppos with white centers seed beads (smallbeads less than 2 mm in diameter) and facetedwound beads (often called ldquoRussian beadsrdquo) Noneof these bead types appear in the Reese Bay collec-tion The comparative data from other Alaskansites indicate that the historical occupation ofReese Bay was very early

The vertical distribution of beads for all unitssupports the idea that the earliest occupation ofthe site was late prehistoric (Table 3) For the mostpart the longhouse was excavated in arbitrary 5cm and 10 cm levels The top 10 cm of the excava-tion included an approximately 5 cm deep sodlayer and it contained over 500 beads This toplayer could contain significant debris from the dis-mantling of the superstructure of the longhouse(Mooney 1993) The second level contained themost beads over 800 and succeeding levels con-tained fewer and fewer The lowest two levels ofexcavation were devoid of trade beads These ear-liest levels did not yield objects of European ori-gin The large concentration of beads and otherhistoric artifacts in the second stratum relative tothe first supports the reports of significantly fewerpeople living in the longhouse in the last years ofits occupation It could also indicate a decliningdemand for beads or a declining bead supply

If bead preference and supply changed veryquickly these changes might be reflected strati-graphically Changes in the Reese Bay assemblagecould provide a basis for a more specific tradebead chronology in the early Russian period How-ever analyses revealed that bead proportionshardly varied with stratigraphic level Woundbead proportions were very consistent throughoutthe deposit with the exception of three ldquorasp-berryrdquo type beads that were found in the upper-

40 Arctic Anthropology 401

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 40

most 10 cm level in one unit The proportions ofdifferent colors and types of small drawn beadsalso showed little change (Fig 6) The composi-tion of the bead assemblage by color and type re-mained very consistent throughout the contact-era

occupation The Reese Bay longhouse floorshowed very little vertical stratification Both thehomogenous assemblage composition and the sin-gle floor suggest that occupation of Longhouse 2may have been relatively short

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 41

Figure 4 Glass trade bead seriation chart modified from Crowell (1997176)

Figure 5 Trade bead assemblage composition The first chart represents the beads collected in 1986 that were usedby Crowell in the 1997 seriation the second chart represents the beads in the current collection

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 41

Cultural Factors Spatial PatterningEthnographic information suggests that horizontalbead distribution might vary based on four mainbehavioral factors status differentiation (and thusunequal access to trade goods) along the east-westaxis of the longhouse burial practices side roomusage and patterns of bead loss The horizontal

distribution of beads from the Reese Bay long-house (Fig 7) is compared to expected patternsbased on these four factors

In order to conduct a distributional analysisthe longhouse was divided in several ways Firstbead distribution in side rooms (ancillary depres-sions) was compared to the distribution in the

42 Arctic Anthropology 401

Table 3 Beads and other artifacts of European origin by stratigraphic depth (below surface)

Depth below Number of trade Number of other objectssurface beads of European origin

0ndash10 cm 550 42

10ndash20 cm 837 95

20ndash30 cm 518 33

30ndash40 cm 199 11

40ndash50 cm 100 9

50ndash60 cm 14 3

60ndash70 cm 0 0

70ndash80 cm 0 0

Total 2218 193

For 48 of the 2266 beads depth was not included in provenience information Those beads are not listedhere

Figure 6 Vertical distribution of drawn beads

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 42

main area of the longhouse Second units associ-ated with human burials were compared to allother units Third distribution of beads of differ-ent sizes and types was compared across all unitsThere were 263 separate units excavated at thelonghouse 25 of which were 1 m 50 cm units intest trenches The remaining units were 1 m2 Bead data are available for only 252 units (all 1 m2) because provenience data for the 1986 excavationsis not in the database at this time

There are several status-related issues thatmight affect bead distribution If toions and theirimmediate families were maintaining control ofthe bead trade one would expect a concentrationof beads (or certain types of beads) at the east endof the longhouse On the other hand if womenandor low-ranking men became middlemen orbrokers of European goods traditional hierarchicalrelationships may have been undermined Thiscould result in a more even distribution of beadsacross areas of the longhouse However becauseUnangan socio-economic organization involved re-distribution an absence of bead concentrations

does not in itself prove that traditional social or-ganization was disrupted

Based on the current collection of beads it isunclear whether differentiation along the east-westaxis exists The longhouse runs from approxi-mately 100 m east to 130 m east on the site gridThe eastern half of the central floor did containthe largest concentrations of beads Since so littleof the western half of the central floor was exca-vated however it is impossible to say whether thebead concentration in the east-central area is theresult of more beads in the eastern part of the long-house or the result of a concentration of beads inthe central floor area in general

Another factor that could have affected beaddistribution is the burial of the dead with beads orin beaded clothing and jewelry Beads are com-monly found in burials across North America Thethree burial areas in the longhouse were near(within 2ndash3 m) bead concentrations Except for theburial in the west trench however none wereclose enough to have been the clear result of burialinclusions

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 43

Figure 7 Horizontal distribution of beads in Longhouse 2

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 43

If side rooms were used as storage areas per-haps beads would be concentrated there until theywere used Other than side room G the rooms hadlower concentrations of beads than the main housefloor It is possible that side room G was used forbead storage However given the relative scarcityof beads in the other side rooms and the lack ofauthoritative ethnographic references to side roomusage this is only speculative

Bead loss patterns provide the best explana-tion for the distribution data Bead loss may havebeen significant when bead-working activitieswere taking place Mooney (1993) suggested thata concentration of beads near the center of thelonghouse resulted from bead working in thearea of greatest available light that is under anentrance ladder suspended from the roof This isalso of course an area of high traffic Bead con-centrations also seem to occur along the northernand southern borders of the central longhousefloor in the trench areas reported to be familyliving and work space It is possible that peoplespent more time in the family areas and the dis-tribution reflects the fact that more beads werelost from clothing and jewelry at those locationsthan in other parts of the house The patternmight also reflect bead-working activity in thoseareas Other bead concentrations in side room Gand in the west trench could also representmanufacturing areas where numbers of beadswere lost No needles were found at the ReeseBay site to corroborate that sewing was takingplace in these areas

In two cases beads were clearly associatedwith each other Four large amber-colored beadsand three ldquoraspberryrdquo beads (large wound beadswith a scored surface) were found in the first stra-tum of one unit in the middle of the longhouse Inboth cases these beads represent the majority ofboth those types In the adjacent unit six largewhite wound beads were found in a row in thesecond stratum These two units are near but notclearly associated with a burial and also containrelatively large numbers of beads overall (45 and30 respectively) perhaps indicating that two in-dividual beaded items were lost or discarded inthe area

Altogether the horizontal distribution of theglass trade beads is somewhat inconclusive withregard to specific behaviors reported ethnographi-cally Mixed results were obtained from the typo-logical and distributional analyses of the glasstrade bead collection from Longhouse 2 at theReese Bay site The bead types and their vertical

distribution confirm that the longhouse was occu-pied in the late prehistoric and very early historicperiods However the horizontal distribution ofthe beads proved difficult to interpret

Summary and ConclusionsGlass trade beads are one of the most ubiquitousand useful artifacts in historic North Americansites Like ceramics beads preserve well werehighly desired by many Native groups and aretime diagnostic to an extent Unlike ceramicsbeads carry no makerrsquos marks It can be difficult totrace the origins and routing of glass beads boundfor North America Some researchers are now em-ploying chemical analyses to source glass (Crowell1994 1997) and hopefully in the future these tech-niques will improve provenance studies Nonethe-less bead research is still relevant to many otheravenues of inquiry especially for the early Russiancontact period in Alaska

Beads are an important component of theReese Bay assemblage making up over 90 of thehistorical artifacts in Longhouse 2 at the site Theassortment of bead types in the collection is consis-tent with early reports of bead preferences and useThis information provides an independent line ofevidence by which to evaluate the observations ofearly European visitors Also the characteristics of the bead collection are consistent with a veryearly historical occupation The concentration ofhistorical artifacts in the second stratigraphic levelof the site and the lack of those artifacts past 60 cmbelow the surface corroborate the early date

In addition to their utility for those interestedin the chronology of the early Russian contact pe-riod in the Aleutians beads also represent the endproduct of a complex relationship between cul-tures Russia was fighting for a foothold in the Pa-cific that would fill the state coffers and providethe country the respectability a colonial powercommanded in eighteenth century Europe Indi-vidual Russian promyshlenniki sought wealth andthe less tangible status denied them in their homecountry Unangan people were involved in theirown status hierarchy one that may have been dis-turbed by the introduction of trade goods Socialstructure and relationships were also affected bydepopulation warfare with Russians and forcedsea mammal hunting

Glass trade beads were a means to an end forboth Russians and Alaska Natives For promyshlen-niki procurement of the furs they wanted requiredthe expertise of Unangan sea mammal hunters En-

44 Arctic Anthropology 401

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 44

listing those hunters alternately (and concurrently)involved enticement coercion and outright forceUnangan people actively sought beads of certainkinds to be used in personal ornamentation Theuse of beads was reflected to a limited (and some-what speculative) extent in the horizontal distribu-tion of the beads The distribution of the beads mayhave been created and affected by several factorsboth behavioral and depositional roof fall from thedismantling of the longhouse superstructure peri-odic housecleaning by the residents of Longhouse2 bead working techniques and bead working ar-eas changing status relationships within the long-house or a mistaken perception of statuslocationarrangements by Veniaminov Data from Reese Bayprovide insight into the chronology and nature ofoccupation at the site While beads are often only asmall part of the information recovered during anexcavation they can provide a wealth of informa-tion about the inhabitants of the site internationalexchange and sociopolitical transformations in thecontact period

Acknowledgments The Reese Bay study part ofthe Unalaska Archaeology and History Project wasfunded by the National Science Foundation(8806802) the National Endowment for the Hu-manities (RO 21690-88) the National GeographicSociety the Alaska Humanities Forum the Univer-sity of Alaska and the Aleut Corporation AllenMcCartney and Douglas Veltre along with Drs JeanAigner and Lydia Black served as co-principal in-vestigators for the Reese Bay project The Univer-sity of Arkansas Peninsula Airways ReeveAleutian Airways MarkAir and Northern AirCargo provided valuable in-kind support TheOunalashka Corporation generously provided in-kind support and permission to investigate the siteFinally the fieldwork would not have been possibleor enjoyable without the enthusiastic assistance ofnumerous residents of Unalaska and the 35 fieldcrew members who worked at Reese Bay between1986 and 1990 The authors also wish to thank Susan Kaplan Jon Erlandson Scott Fitzpatrick andan anonymous reviewer for thoughtful commentsthat have substantially improved this paper

References CitedBeaglehole J C1967 The Journal of Captain James Cook on His Voy-

age of Discovery 3(2) Cambridge CambridgeUniversity Press

Berkh Vasilii N[1823] A Chronological History of the Discovery of the 1974 Aleutian Islands Ontario The Limestone Press

Black Lydia T1988 The Story of Russian America In Crossroads of

Continents W Fitzhugh and A Crowell edsPp 70ndash82 Washington DC Smithsonian Insti-tution Press

1991 Unalaska Archaeology and History Project Na-tional Geographic Research and Exploration7(4)490ndash497

Black Lydia T and R G Liapunova1988 Aleut Islanders of the North Pacific In Cross-

roads of Continents W Fitzhugh and A Crow-ell eds Pp 52ndash57 Washington DCSmithsonian Institution Press

Bundy Barbara E1998 Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Is-

land Masterrsquos thesis Department of Anthropol-ogy University of Arkansas

Coxe William1780 The Russian Discoveries between Asia and

America March of America Facsimile SeriesReprint 1966 Ann Arbor University Micro-films

Crowell Aron L1994 World Systems Archaeology at Three Saints

Harbor an Eighteenth Century Russian FurTrading Site on Kodiak Island Alaska PhDdissertation Department of Anthropology Uni-versity of California at Berkeley

1997 Archaeology and the Capitalist World System AStudy from Russian America New YorkPlenum Press

Dmytryshyn B E A P Crownhart-Vaughn andT Vaughn1988 Introduction In Russian Penetration of the

North Pacific Ocean B Dmytryshyn E A PCrownhart-Vaughn and T Vaughn edsPp xxxindashlxxxiii Portland Oregon HistoricalSociety Press

Francis Peter Jr1988 Report on the beads from Reese Bay Unalaska

Ornament Autumn

1994 Beads at the Crossroads of Continents In An-thropology of the North Pacific Rim WFitzhugh and V Chaussonet eds Pp 281ndash305Washington DC Smithsonian Institution Press

Gibson James R1969 Feeding the Russian Fur Trade Madison Uni-

versity of Wisconsin Press

1976 Imperial Russia in Frontier America New YorkOxford University Press

1990 Furs and Food Russian America and the Hud-son Bay Company In Russian America TheForgotten Frontier B S Smith and R J Barnetteds Pp 41ndash54 Tacoma Washington HistoricalSociety

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 45

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 45

Graeber David1996 Beads and Money Notes toward a Theory of Wealth

and Power American Ethnologist 23(1)4ndash24

Grumet Robert S1995 Historic Contact Indian People and Colonists in

Todayrsquos Northeastern United States in the Six-teenth through Eighteenth Centuries NormanUniversity of Oklahoma Press

Inter-Society Color Council (ISCC) and National Bureauof Standards (NBS)1955 ISCC-NBS Color-Name Charts Illustrated with

Centroid Colors (Supplement to NBS circular533 The ISCC-NBS Method of DesignatingColor and a Dictionary of Color Names) Wash-ington DC US Government Printing Office

Jochelson Vladimir I1933 History Ethnology and Anthropology of the

Aleut Washington DC Carnegie Institute ofWashington Publication no 432

Karklins Karlis1982 Guide to the Description and Classification of

Glass Beads History and Archaeology no 59National Historic Parks and Sites Branch ParksCanada Ottawa

Khlebnikov Kiril Timofeevich1994 Notes on Russian America Parts IIndashV Kadiak

Unalashka Atkha the Pribylovs Ontario TheLimestone Press

Kidd Kenneth E1979 Glass Bead Making from the Middle Ages to the

Early Nineteenth Century History and Archae-ology no 30 Parks Canada Ottawa

Kidd Kenneth E and Martha Ann Kidd1970 A Classification System for Glass Beads for the

Use of Field Archaeologists Canadian HistoricSites Occasional Papers in Anthropology andHistory no 1 Ottawa

Lantis Margaret1984 Aleut In Handbook of North American Indians

vol 5 Arctic David Damas ed Pp 161ndash184Washington DC Smithsonian Institution Press

Laughlin William S1980 Aleuts Survivors of the Bering Land Bridge Ft

Worth Holt Rinehart and Winston

Laughlin William S and Jean S Aigner1975 Aleut Adaptation and Evolution In Prehistoric

Maritime Adaptations of the Circumpolar ZoneW Fitzhugh ed Pp 181ndash202 Paris Mouton

Liapunova Roza G1996 Essays on the Ethnography of the Aleuts (at the

End of the Eighteenth and the First Half of theNineteenth Century) Fairbanks University ofAlaska Press

McCartney Allen P1984 Prehistory of the Aleutian region In Handbook

of North American Indians vol 5 Arctic

David Damas ed Pp 119ndash135 WashingtonDC Smithsonian Institution Press

McCartney Allen P and Douglas W Veltre1999 Aleutian Islands Prehistory Living in Insular

Extremes World Archaeology 30(3)503ndash516

In Longhouses of the Eastern Aleutian Islands press Alaska In To the Aleutians and Beyond The An-

thropology of William S Laughlin B FrohlichA B Harper and R Gilberg eds Publications ofthe National Museum Ethnographical Series vol20 Copenhagen Department of EthnographyThe National Museum of Denmark

McCartney Allen P Douglas W Veltre Jean A Aignerand Lydia T Black1988 Preliminary Report of Research Conducted by

the Unalaska Archaeology and History Projectduring 1988 Report submitted to the NationalScience Foundation

1990 Unalaska Archaeology and History Project Pre-liminary Report of Operations 1989 Report sub-mitted to the National Endowment for theHumanities

Makarova R V1975 Russians on the Pacific 1743ndash1799 Ontario

The Limestone Press

Merck Carl Heinrich[1788ndash Siberia and Northwestern America 1788ndash1792 1792] The Journal of Carl Heinrich Merck Naturalist 1980 with the Russian Scientific Expedition Led by

Captains Joseph Billings and Gavriil SarychevOntario The Limestone Press

Miller Polly G1994 Early Contact Glass Trade Beads in Alaska Alta-

monte Springs The Bead Society of CentralFlorida

Mitchem Jeffrey M and Jonathan M Leader1988 Early 16th Century Beads from the Tatham

Mound Citrus County Florida Data and Interpre-tations The Florida Anthropologist 41(1)42ndash60

Mooney James P1993 An Eighteenth Century Aleutian Longhouse at

Reese Bay Unalaska Island Masterrsquos thesis De-partment of Anthropology University ofArkansas

Murie Olaus J1959 Fauna of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska Penin-

sula United States Department of the InteriorNorth American Fauna Series no 61

Ozhegov S I1989 Slovarrsquo Russkogo Yazuika Moskva Russkii

Yazuik

Pagden Anthony1995 Lords of All the World Ideologies of Empire in

Spain Britain and France c1500ndash1800 NewHaven Yale University Press

46 Arctic Anthropology 401

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 46

Pielou E C1991 After the Ice Age The Return of Life to

Glaciated North America Chicago University ofChicago Press

Rollings Willard H1992 The Osage An Ethnohistory of Hegemony on

the Prairie Plains Columbia University of Mis-souri Press

Sarychev Gavriil Andreyevich1806 Account of a Voyage of Discovery to the North-

East of Siberia the Frozen Ocean and theNorth-East Sea London Richard Phillips

Scott Vanya R1990 A Preliminary Analysis of Reese Bay Trade

Beads Northwest Quadrant 1989 Season Un-published undergraduate paper for Anthropol-ogy 480 On file with Dr Douglas VeltreDepartment of Anthropology University ofAlaska Anchorage

Shelikov Grigorii I1980 A Voyage to America 1783ndash1786 translated by

M Ramsay R A Pierce ed Ontario The Lime-stone Press

Spector Janet D1976 The Interpretive Potential of Glass Trade Beads

in Historic Archaeology Historical Archaeology1017ndash27

Sprague Roderick1985 Glass Trade Beads A Progress Report Historical

Archaeology 19(2)87ndash105

Stone Lyle1970 Archaeological Research at Fort Michilimack-

inac an Eighteenth Century Historic Site in Em-mett County Michigan 1959ndash1966 ExcavationsPhD dissertation Department of AnthropologyMichigan State University

Titova Z D1980 Voyage of Mr Billings from Okhotsk to Kam-

chatka his arrival there setting out for the Ameri-can Islands return to Kamchatka second seavoyage to those islands from the north thence toBering Strait and Chukotskii nos 1789ndash1790ndash1791 From Etnograficheskie materialySevero-Vostochnoi Geograficheskoi Ekspeditsii1785ndash1795 Extract from original manuscriptpublished in Siberia and Northwestern America1788ndash1792 The Journal of Carl Heinrich MerckNaturalist with the Russian Scientific ExpeditionLed by Captains Joseph Billings and GavriilSarychev Ontario The Limestone Press

van Der Sleen W G N1973 A Handbook on Beads York Liberty Cap Books

Veltre Douglas W1990 Perspectives on Aleut Culture Change during the

Russian Period In Russian America The ForgottenFrontier B S Smith and R J Barnett edsPp 175ndash83 Tacoma Washington Historical Society

Veltre Douglas W and Allen P McCartney2001 Ethnohistorical Archaeology at the Reese Bay

Site Unalaska Island In Archaeology of theAleut Zone of Alaska D Dumond edPp 87ndash104 University of Oregon Anthropologi-cal Papers no 58 Eugene University of Oregon

Veniaminov Ivan[1940] Notes on the Islands of the Unalashka District 1984 L T Black and R H Geoghegan trans Ontario

The Limestone Press

von Langsdorff Georg Heinrich1993 Remarks and Observations on a Voyage Around

the World from 1803ndash1807 Volume 1 OntarioThe Limestone Press

Woodward Arthur1989 Indian Trade Goods Portland Binford and Mort

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 47

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 47

contact period an older midden and smallerhouses of an indeterminate period (McCartneyand Veltre in press Veltre and McCartney 2001)Longhouse 2 was tested in 1986 and partially excavated in the late 1980s by the Unalaska His-tory and Archaeology Project (McCartney et al1988 1990)

More than 2000 glass trade beads were re-covered from the longhouse excavation Thisbead collection is used to consider differentquestions about the community at Reese BayFirst the occupation of the site in historic timescan be dated by seriating the beads a techniquesuccessfully applied in other areas of Alaska(Crowell 1994) Second the distribution of thebeads within the site may reflect Native socialstructure during the early Russian contact pe-riod especially in terms of gender and statusUnderstanding changes in bead use through time provides insight into how Alaska Nativecommunities adapted to both the stresses andthe opportunities of Russian contact With thosegoals in mind the ethnohistorical documenta-tion of the glass bead trade in the early Russianperiod is reviewed and the composition anddistribution of the Reese Bay trade bead assem-blage is compared to historically reported pat-terns of bead use

Trade Beads and Historical Archaeology

Russian traders and explorers left few descriptionsof traditional Unangan and Eskimo cultures as theyexisted at the time of contact although by the nine-teenth century a few clergymen were writing de-tailed accounts (Black 1988) The accounts likemany colonial documents are difficult to interpretEven with the best of intentions first-time observersof a culture can easily form misconceptions that arereflected in text and illustrations a process Grumet(19957) called ldquocreative misunderstandingrdquo It fallsto archaeologists to clarify the history of this impor-tant era of upheaval and culture change

Archaeological data have much to offer in thesearch for a balanced history of the European oc-cupation of North America Trade bead analysiscan clarify a number of theoretical issues for sev-eral reasons Beads have played an important rolein European trade with local groups all over theworld This ubiquity provides an excellent basefor comparing European and Native American re-lations at different times and places Also glasstrade beads can be ldquoa reliable dating indexrdquo if ar-chaeological and ethnohistorical sources are com-bined (Spector 197617) Woodward (1965) notedthat trade bead preferences among Native groups

30 Arctic Anthropology 401

Figure 1 Unalaska Island (north portion) showing location of Reese Bay site

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 30

often changed quickly making time-definitionrather precise In fact trade beads have been suc-cessfully used as diagnostic artifacts for determin-ing dates of occupation and sources of trade goods(eg Crowell 1994 Mitchem and Leader 1988) Fi-nally beads often functioned differently in Euro-pean economies than in Native economies Therole of beads (and other ornaments) has often beenlikened to that of coin money in a traditionalWestern market system because they are ldquoroughlycommensurable and highly portablerdquo (Graeber19964) Their use by Native groups however wasprobably also influenced by the importance of sta-tus rules preferences regarding ornamentationand perhaps the individual history of the beadedobjects (Woodward 196518) All of these consider-ations dictated the value of the beads and the uni-verse of possibilities for their distribution (Graeber1996) Finally beads are easily lost mitigating theeffects of curation of artifacts during site use and

abandonment Given these qualities it should bepossible to discuss spatial patterning of beads withreference to social and economic structure in rap-idly changing and adapting societies

Glass trade bead studies have been ap-proached in many different ways depending onthe research goals of the project Typical interestsare dating site occupation determining the man-ufacturing origin of the beads understanding theavailability of beads and the preferences of beadconsumers discussing the use of beads duringsite occupation and inferring the causes of beadloss and disposal (Francis 1994) Bead use andloss patterns reflect consumer preferences beadavailability and other rules of ownership and or-namentation Archaeological patterning may alsobe the result of beaded-item manufacture and re-lated issues like the availability of beading materi-als (eg fine needles thread) and visibilitySpector (1976) suggested that bead researchers

Bundy et al Glass Trade Beads from Reese Bay Unalaska Island 31

Figure 2 The Reese Bay site (UNL-063) from McCartney et al (19885)

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 31

use both ethnohistorical and archaeological datato accurately classify and describe beads and tounderstand how they were perceived and used byNative and European groups

The Aleutian IslandsClimate and GeographyThe Aleutian Islands begin with Unimak Islandjust west of the Alaska Peninsula and extend about1100 miles to Attu Island The windswept islandsare home to a diverse marine environment (Pielou1991130) Sea otters sea lions and hair seals arepresent year-round as are many intertidal shell-fish species due to the absence of winter ice(Murie 1959) Whales fur seals migratory birdssalmon and plant foods are available seasonally(Laughlin and Aigner 1975) Halibut and cod arepresent year round but are more easily obtainedduring certain seasons when they move inshoreThe many bays and inlets that mark the shores ofthe islands increase the amount of coastline avail-able and provide sheltered landings for both hu-mans and their prey (McCartney 1984) Althoughit appears inhospitable the Aleutian environmenthas provided sufficient resources to maintain a hu-man community for over 8000 years (McCartney1984 McCartney and Veltre 1999)

The Unangan PeopleMost of the historical information about Unanganculture during the second half of the eighteenthcentury comes from reports given by seafarers andImperial employees to the Russian government(Liapunova 1996133) It was not until the firsthalf of the nineteenth century that Bishop I Veni-aminov ([1840] 1984) made the first effort to com-prehensively document Unangan life (Liapunova199631) Several researchers have gleaned the fol-lowing description of early contact-era Unanganculture from early reports Veniaminovrsquos worksand archaeological data

The Aleutian cultural tradition at the time ofEuropean contact and long before was character-ized by a very effective focus on marine resources(Laughlin 1980 McCartney 1984) Seals whalesotters and occasionally walrus were hunted at sea(Liapunova 199689) Although Russians claimedthat ldquothe love of the Aleut for catching sea otterssurpasses any descriptionrdquo (Russian Naval Officerquoted in Gibson 19768) Laughlin (198042) sug-gested that the animals were infrequently huntedprior to Russian demands for their pelts Youngboys trained rigorously to perfect their endurance

and hunting techniques and Europeans nevermatched the efficiency and skill of Unangan seamammal hunters (Laughlin 198029 44) Othermarine resources like fish birds and shellfishwere also collected (Jochelson 193351 Lantis1984) Plentiful resources and wet weather en-sured that ldquonot much food was stored except forthe festivalsrdquo (Lantis 1984176)

Unangan socio-political organization at thetime of Russian contact resembled that of othernorthern coastal groups including Alutiiq andTlingit (Lantis 1984) Like the Tlingit Unangan so-ciety was divided into three groups elites com-moners and slaves (Liapunova 1996138ndash139)The elite group consisted of toions (chiefs) actingas household heads and their direct descendantsA toion oversaw kin-controlled hunting groundsand enforced behavioral norms but ldquoit may be thatkin membership was separate from inheritance ofoffice or privileged positionrdquo (Lantis 1984176)Laughlin (198058ndash59) noted that household headswere also expected to be unusually strong and suc-cessful hunters Thus while status was indicatedby descent it was not ensured

Eastern Aleutian Islanders lived in semi-subterranean longhouses that Russians calledbarabari or yurts (Laughlin 198050 McCartneyand Veltre in press) A longhouse contained sev-eral families who were related in a variety of waysin that ldquorules of residence did not seem to bestrictly enforcedrdquo (Lantis 1984176) Veniaminov([1840] 1984) reported that residence within thelonghouse was determined by status with thehighest-status individuals living at the east endand others continuing in descending order Nu-clear families had living and sleeping space alongthe walls of the structure and side rooms wereused for storage or additional living space (Veni-aminov [1840] 1984262) Assessments of howmany people lived in a single longhouse vary but afairly conservative estimate might be 40 residents(Laughlin 198050)

Unangan life was patterned not only by thedemanding environment but also by strong cul-tural traditions Understanding how these tradi-tions changed as Unangan people adapted toRussian contact is central to historical archaeologyand ethnohistory in the Islands

Russian AmericaRussian actions in the New World were deter-mined by economic goals and restrictions envi-ronmental constraints religious convictions andthe cultural traditions of Russian and Native

32 Arctic Anthropology 401

arc00000_bundyqxd 81603 1208 PM Page 32