GAO-16-827, Federal Fisheries Management: Additional ...

Transcript of GAO-16-827, Federal Fisheries Management: Additional ...

FEDERAL FISHERIES MANAGEMENT

Additional Actions Could Advance Efforts to Incorporate Climate Information into Management Decisions

Report to Congressional Requesters

September 2016

GAO-16-827

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-16-827, a report to congressional requesters

September 2016

FEDERAL FISHERIES MANAGEMENT

Additional Actions Could Advance Efforts to Incorporate Climate Information into Management Decisions

What GAO Found The Department of Commerce’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and eight Regional Fishery Management Councils (Council) have general information on the types of effects climate change is likely to have on federally managed fish stocks but limited information on the magnitude and timing of effects for specific stocks. They also face several challenges to better understand these effects, based on GAO’s analysis of NMFS and Council questionnaire responses, NMFS and Council documentation, and interviews with NMFS and Council officials. For example, NMFS officials said that northern rock sole may adapt to warming ocean temperatures more easily than other fish species, but it is unknown how such temperatures may affect the timing of the fish’s life cycle events, such as spawning. NMFS and Council officials identified several challenges to better understand potential climate change effects on fish stocks, including determining whether a change in a stock’s abundance or distribution is the result of climate change or other factors, such as overfishing in the case of Atlantic cod.

Atlantic Cod

NMFS developed a climate science strategy in 2015 to help increase the use of climate information in fisheries management. The strategy lays out a national framework to be implemented by NMFS’ regions but does not provide specific guidance on how climate information should be incorporated into the fisheries management process. An NMFS official said that developing such guidance has not been an agency priority, but as knowledge on climate change progresses there is a more pressing need to incorporate climate information into fisheries management decision making. Developing such guidance would align with federal standards for internal control and may help NMFS ensure consistency in how its regions and the Councils factor climate-related risks into fisheries management. In addition, NMFS has not developed agency-wide performance measures to track progress toward the strategy’s overall objectives, a leading practice. NMFS officials said they are waiting to finalize regional action plans for implementing the strategy before determining whether such measures may be necessary. GAO reviewed the proposed measures in NMFS’ draft regional action plans and found that they aligned with some key attributes of successful performance measures. But, most of the measures did not contain other key attributes, such as measurable targets. By incorporating key attributes when developing performance measures and assessing whether agency-wide measures may also be needed, NMFS may be in a better position to determine the extent to which the objectives of its strategy overall are being achieved.

View GAO-16-827. For more information, contact Anne-Marie Fennell at (202) 512-3841 or [email protected].

Why GAO Did This Study NMFS and the Councils manage commercial and recreational marine fisheries that are critical to the nation’s economy. The effects of climate change may pose risks to these fisheries that could have economic consequences for the fishing industry and coastal communities, according to the 2014 Third National Climate Assessment.

GAO was asked to review federal efforts to address the effects of climate change on federal fisheries. This report examines (1) information NMFS and the Councils have about the existing and anticipated effects of climate change on federally managed fish stocks and challenges to better understand these effects and (2) efforts NMFS has taken to help it and the Councils incorporate climate information into fisheries management. GAO analyzed responses to its questionnaire from all NMFS regions and the Councils, analyzed seven nongeneralizable fish species selected to reflect variation in the potential effects of climate change, reviewed relevant documentation, and interviewed NMFS and Council officials.

What GAO Recommends GAO recommends that NMFS (1) develop guidance on incorporating climate information into the fisheries management process and (2) incorporate key attributes of successful performance measures in the regional action plans and assess whether agency-wide measures for the climate science strategy may be needed. The agency agreed with GAO’s recommendations.

Page i GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

Letter 1

Background 6 NMFS and the Councils Have Limited Information on the

Magnitude and Timing of Climate Change Effects on Fish Stocks 14

NMFS Developed a Strategy to Help Incorporate Climate Information into Fisheries Management, but It Is in the Early Stages of Implementation 24

Conclusions 30 Recommendations for Executive Action 31 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 31

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 33

Appendix II Key Attributes of Successful Performance Measures 37

Appendix III Comments from the Department of Commerce 38

Appendix IV GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 41

Tables

Table 1: NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy (Strategy) Priority Objectives 28

Table 2: Key Attributes of Successful Performance Measures 37

Figures

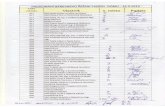

Figure 1: Boundaries of National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Regions and the Regional Fishery Management Councils (Council) 8

Figure 2: General Steps in the Federal Fisheries Management Process 11

Contents

Page ii GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

Abbreviations Council Regional Fishery Management Council ISO International Organization for Standardization Magnuson-Stevens Act Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976, as amended NMFS National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration Strategy NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

441 G St. N.W. Washington, DC 20548

September 28, 2016

The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse Ranking Member Subcommittee on Fisheries, Water, and Wildlife Committee on Environment and Public Works United States Senate

The Honorable Robert Menendez United States Senate

The Honorable Jeff Merkley United States Senate

Commercial and recreational marine fisheries are critical to the nation’s economy, contributing approximately $100 billion to the U.S. gross domestic product and supporting more than 1.8 million jobs in 2014.1 These fisheries may be vulnerable to the increasing effects of climate change in the oceans—including physical changes such as warmer surface temperatures and chemical changes such as higher acidity levels—which could affect the abundance and distribution of fisheries, according to the U.S. Global Change Research Program’s 2014 Third National Climate Assessment.2 This assessment also reports that changes in the abundance and distribution of certain fisheries could have economic consequences for the communities and industries that depend on harvesting the affected fish, for example, by reducing the availability of some commercially and recreationally important fish species.

1National Marine Fisheries Service, Fisheries Economics of the United States, 2014, U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Technical Memorandum NMFS-F/SPO-163 (Silver Spring, Md: 2016). The information on gross domestic product and jobs includes data on commercial seafood harvesters, processors, dealers, wholesalers, distributors, importers, and retailers, as well as recreational fishing trips and fishing equipment for state and federally managed fisheries. For the purposes of this report, the terms fisheries and fisheries management refer to marine fisheries that are at least in part federally managed and include fish and invertebrate species, such as shellfish. 2Jerry M. Melillo, Terese (T. C.) Richmond, and Gary W. Yohe, eds., Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, U.S. Global Change Research Program (Washington, D.C.: 2014).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

The federal government serves as a financial backstop to the fishing industry by providing disaster assistance in the event of a fishery disaster. For example, a fishery disaster can be declared after the Secretary of Commerce determines that a commercial fishery failure under certain conditions has occurred.3 The federal government provided more than $640 million in federal fishery disaster assistance from 2005 through 2015, according to Department of Commerce data.4 The effects of climate change could negatively affect fisheries and contribute to future fishery disasters, according to the Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).5 The effects of climate change, in general, may also increase the fiscal exposure to the federal government—limiting the federal government’s fiscal exposure by better managing climate change risks has been on our high-risk list since 2013,

3Under provisions of the Magnuson-Stevens Act and the Interjurisdictional Fisheries Act, the federal government may provide fishery disaster assistance in certain circumstances. See 16 U.S.C. §§ 1861a(a), 1864, 4107(b), 4107(d). A commercial fishery failure occurs when commerce in, or revenue from commerce in, a fishery materially decreases or is markedly weakened due to a fishery resource disaster, such that those engaged in the fishery suffer severe economic hardship. There is no standing fund for fishery disaster relief, so when the Secretary determines that a fishery disaster has occurred, Congress is to decide whether, and how much, to appropriate in disaster assistance. 4This is the amount that was appropriated for federal fishery disaster assistance under sections 312(a) and 315 of the Magnuson-Stevens Act or sections 308(b) and 308(d) of the Interjurisdictional Fisheries Act, according to officials from the Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 5NOAA cited the potential for climate change to amplify conditions—such as harmful algal blooms and changes in ocean temperatures—that can negatively affect fish stocks as part of its justification for its 2016 proposal to establish a fund to improve the environmental and economic resilience of fisheries declared a disaster by the Secretary. See National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Budget Estimates Fiscal Year 2017 (Washington, D.C.: 2016).

Page 3 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

in part, because of concerns about the increasing costs of federal disaster response and recovery assistance.6

NOAA is the lead federal agency responsible for managing commercial and recreational marine fisheries. Specifically, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976, as amended (Magnuson-Stevens Act), sets forth national standards for federal fisheries conservation and management.7 Under the act, NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and eight Regional Fishery Management Councils (Council) are responsible for fisheries management and conservation in federal waters.8 NMFS generally serves as the lead agency—in collaboration with partners from the states, academia, and elsewhere—for developing scientific information on federally managed fish stocks, including through stock assessments—reports that contain information on fish biology, abundance, and distribution.9 NMFS and the Councils then use this information to develop

6GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO-13-283 (Washington, D.C.: February 2013). We updated the high-risk list again in 2015; see GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO-15-290 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2015). We previously found that the federal government does not budget for the costs of supplemental appropriations for relief for major disasters, and that without proper budgeting and forecasting to account for such events, the government runs the risk of facing a large fiscal exposure at any time. The term fiscal exposure refers to the responsibilities, programs, and activities that may either legally commit the federal government to future spending or create the expectation for future spending. See GAO, Fiscal Exposures: Improving Cost Recognition in the Federal Budget, GAO-14-28 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 29, 2013). Also, see GAO’s Federal Fiscal Outlook webpage (here). 7Pub. L. No. 94-265, § 301(a) (1976) (codified as amended at 16 U.S.C. § 1851(a)). 8The Councils are supported by federal funds and generally comprise NMFS regional administrators, state officials, and members of the fishing industry and conservation groups as voting members, as well as other nonvoting members, such as officials from other federal agencies. The Magnuson-Stevens Act establishes requirements for the selection of certain voting members for each Council. NMFS provides guidance to the Councils on how they are to implement their fisheries management responsibilities. 9A fish stock refers to either one species or a complex of comparable species managed as an entity in a specific geographic area. When possible, NMFS uses biology to help identify a stock’s geographic boundaries, according to NMFS officials. In some cases, individual species are managed as multiple stocks, based on geographic location. For example, in the Alaska region, walleye pollock are managed as four separate stocks based on their geographic distribution in different areas of the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska. This report primarily uses the term fish stock since this is generally the unit of management for federal fisheries. In instances where we obtained information at the fish species level, we use the term species.

Page 4 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

and implement fishery management plans, which contain practices fisheries managers are to follow in managing each fishery and in setting annual catch limits.10 Annual catch limits establish the limit on the amount of fish that can be harvested annually for specific fish stocks.

You asked us to review federal efforts to address the effects of climate change on federal fisheries management. This report examines (1) information NMFS and the Councils have about the existing and anticipated effects of climate change on federally managed fish stocks and challenges they face to better understand these effects and (2) efforts NMFS has taken to help it and the Councils incorporate climate information into the fisheries management process.

To examine information NMFS and the Councils have about the effects of climate change on federally managed fish stocks and challenges they face to better understand these effects, we reviewed scientific studies and other documentation prepared by NMFS, the Councils, and others such as academics. We also developed a questionnaire of open-ended questions, which we disseminated to the five NMFS regional offices and the eight Councils to obtain their views on the information they have about the effects of climate change on the fish stocks they manage and any challenges they face to better understand these effects, among other things. All five NMFS regions and the eight Councils responded.11 We analyzed their responses to identify key themes, which we attribute in this report to NMFS and Council officials. In addition, we analyzed a nongeneralizable sample of seven fish species as case studies.12 We selected the seven species to reflect a range of potential effects of climate change and variation in the value and volume of commercial

10For the purposes of this report, the term fisheries managers refers to the different entities involved in making management decisions for federally managed fisheries, including NMFS and the Councils. In instances where a fishery occurs in both federal and state waters, NMFS and the Councils may also work with individual states or interstate regional bodies, such as the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, in the management of the fishery. 11NMFS’ regional offices and regional Fisheries Science Centers—which are responsible for conducting research and providing scientific advice, among other things—worked together to produce coordinated regional responses to the questionnaire. 12These case studies are intended to provide illustrative examples only and cannot be projected to the entire universe of fish species.

Page 5 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

harvests, based on NMFS’ commercial fisheries data from 2008 to 2013. We assessed the reliability of these fisheries data and found them to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of selecting case study species.

To examine efforts NMFS has taken to help it and the Councils incorporate climate information into the fisheries management process,13 we analyzed the questionnaire responses provided by the NMFS regions and Councils and reviewed agency and Council documentation, such as the NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy (Strategy).14 We compared this information to leading practices in risk management and federal standards for internal control and assessed the Strategy against leading practices in strategic planning and performance measurement.15 For both objectives, we also interviewed officials from NMFS’ headquarters and two regions (Greater Atlantic and Alaska), as well as representatives from four Councils (New England, Mid-Atlantic, South Atlantic, and North

13Our analysis of steps taken to incorporate climate information into the fisheries management process focused on the process for setting annual catch limits and related management actions. The Magnuson-Stevens Act requires the Councils to develop annual catch limits for each of their managed fisheries, and NMFS officials described this responsibility as a major part of the fisheries management process. According to NMFS officials, other fishery management actions (such as managing the conservation of fish habitat) may follow different processes, which we did not include in our analysis. 14Jason S. Link, Roger Griffis, and Shallin Busch, eds., NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy, U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-F/SPO-155 (Silver Spring, Md: 2015). The Strategy is available here. 15For leading practices in risk management, see International Organization for Standardization, ISO 31000 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines (2009). The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is a worldwide federation of national standards bodies. ISO 31000:2009 Risk management – Principles and guidelines is available here. For internal control standards, see GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO/AIMD-00-21.3.1 (Washington, D.C.: November 1999). We have revised and reissued our standards for internal control, with the new revision effective as of October 1, 2015. See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014). For examples of leading practices in strategic planning and performance measurement, see GAO, Tax Administration: IRS Needs to Further Refine Its Tax Filing Season Performance Measures, GAO-03-143 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 22, 2002); Executive Guide: Effectively Implementing the Government Performance and Results Act, GAO/GGD-96-118 (Washington, D.C.: June 1996); and Agencies’ Annual Performance Plans Under the Results Act: An Assessment Guide to Facilitate Congressional Decisionmaking, GAO/GGD/AIMD-10.1.18 (Washington, D.C.: February 1998).

Page 6 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

Pacific) and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission.16 To obtain broader perspectives, we also interviewed representatives from 11 stakeholder organizations selected to reflect geographic diversity and different types of involvement in fisheries management issues, including fishing industry groups, conservation groups, and a nonprofit serving Alaska Natives. Appendix I contains a more detailed description of our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2014 to September 2016 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

NMFS—operating through its headquarters, five regional offices, and six regional Fisheries Science Centers—and the eight Councils are responsible for managing approximately 470 fish stocks in federal waters across five geographic regions of the country (see fig. 1 for the NMFS region and Council boundaries).17 Federal waters generally extend from 3 to 200 nautical miles off the coast of the United States.18 In fiscal year

16We selected these entities for interviews because they are involved in managing fisheries in regions of the country that are expected to experience significant effects from climate change, according to NMFS documentation and our discussions with agency officials. 17The 470 fish stocks include some stock complexes where comparable species are managed together as one entity in a specific geographic area. In addition to NMFS’ fisheries management responsibilities, the agency is also responsible for, among other things, managing marine species listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. 18Coastal states generally maintain responsibility for managing fisheries in waters that extend approximately 3 geographic miles from their coastlines. In the 1940s, the federal government authorized three interstate compacts, each creating a regional interstate marine fisheries commission to better utilize and protect fisheries within the consenting states’ jurisdictions. The three commissions represent the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific states, respectively. Legislation passed in the 1980s and 1990s gave the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission some independent regulatory authority over some species. This commission is now directly involved in the management of more than 20 fish stocks in state waters, including some stocks that are concurrently managed by NMFS and the Councils in federal waters.

Background

Page 7 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

2016, NMFS’ budget for its fisheries science and management activities, such as conducting stock assessments and developing fisheries management guidance, was approximately $536.7 million, according to NOAA budget documents.19

19About $33.5 million of the approximately $536.7 million was provided to the Councils and the interstate marine fisheries commissions to support their operating costs.

Page 8 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

Figure 1: Boundaries of National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Regions and the Regional Fishery Management Councils (Council)

Note: The Western Pacific Council includes the Mariana Islands archipelago, American Samoa, and a range of remote island areas in the central and western Pacific not depicted on this map. Coastal states generally are responsible for managing fisheries in waters that extend approximately 3 geographic miles from their coastlines, and NMFS and the Councils manage fisheries in federal waters.

Page 9 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

NMFS has overall responsibility for collecting data on fish stocks and ocean conditions and for generating the scientific information necessary for the conservation, management, and use of marine resources.20 The agency’s six regional Fisheries Science Centers are the primary entities responsible for performing this work, and they collaborate with a variety of partners, such as coastal states, academics, other nations, and members of the fishing industry in doing so. For many fish stocks, the regional Fisheries Science Centers analyze the collected data to conduct stock assessments to estimate, among other things, the size of the population of a fish stock (i.e., the stock’s abundance) and other population dynamics.21 In addition, stock assessments contain information on reference points that can be used to inform management decisions.22 NMFS provides the results of its stock assessments and other analyses, as appropriate, to the Councils for use in implementing their respective fisheries management responsibilities.

The Councils are responsible for a number of steps in the fisheries management process. In particular, the Councils develop and amend fishery management plans for fish stocks, based on guidelines developed by NMFS. Fishery management plans identify, among other things, the conservation and management measures that will be used to manage a fishery, such as fishing equipment restrictions, permitting policies, and restrictions on the timing or location of permissible fishing. The Magnuson-Stevens Act requires the conservation and management measures in fishery management plans to be based on the best scientific information available. The Councils submit proposed plans and plan amendments to NMFS, which is responsible for determining if they are

20We previously reviewed NMFS’ recreational fisheries data collection efforts. See GAO, Recreational Fisheries Management: The National Marine Fisheries Service Should Develop a Comprehensive Strategy to Guide Its Data Collection Efforts, GAO-16-131 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 8, 2015). 21We previously reviewed NMFS’ fish stock assessment prioritization process. See GAO, Fish Stock Assessments: Prioritization and Funding, GAO-14-794R (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 19, 2014). 22Reference points provide targets, thresholds, and other decision criteria used in the fisheries management process, such as determining a numeric threshold that if exceeded would indicate that overfishing had occurred.

Page 10 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

consistent with the Magnuson-Stevens Act and other applicable laws, and for issuing and enforcing final regulations to implement approved plans.23

In implementing fishery management plans, the Councils are responsible for determining the maximum size of each fish stock’s allowable harvest.24 This is generally done by developing annual catch limits for each fish stock, that is, the amount of fish that can be harvested in the year. Figure 2 presents an overview of the federal fisheries management process.

23The Magnuson-Stevens Act authorizes the Secretary of Commerce to approve, disapprove, or partially approve proposed fishery management plans and plan amendments submitted by the Councils. The Secretary has subsequently delegated this responsibility to the NOAA Assistant Administrator for Fisheries. 24The Councils do this in consultation with their scientific and statistical committees, which are advisory bodies made up of members—such as federal and state employees, academics, and independent experts— who are required to have strong scientific or technical credentials and experience and are appointed by the Councils.

Page 11 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

Figure 2: General Steps in the Federal Fisheries Management Process

Note: This figure presents the process for setting annual catch limits and related management actions. The processes followed for other fishery management actions (e.g., managing the conservation of fish habitat) may differ from the process depicted in this figure. For example, the types of data collected and analyzed may vary based on the specific action the data and analyses are intended to support.

Page 12 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

According to the 2014 Third National Climate Assessment, a number of physical and chemical changes to the oceans have been observed or are expected to occur as a result of climate change, largely attributable to increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, such as carbon dioxide.25 For instance, surface temperatures for the ocean surrounding the United States and its territories warmed by more than 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit over the past century, according to the 2014 assessment. Changes in ocean temperature have varied, with the oceans off the coasts of Alaska and parts of the northeastern United States, for example, warming more rapidly than other areas. The 2014 assessment notes that warming has several consequences and can lead to a number of other physical changes in the ocean, such as the thermal expansion of sea water, which may contribute to rising sea levels. Increases in ocean surface temperatures may also alter ocean circulation by reducing the vertical mixing of water that brings nutrients to the surface and oxygen to deeper waters, which could affect the availability of nutrients and oxygen for marine life in different locations, according to the 2014 assessment.

Increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have also contributed to chemical changes in the oceans. According to the National Research Council, scientists estimate that the world’s oceans have absorbed approximately 30 percent of the carbon dioxide emitted by human activities over the past 200 years.26 As atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide increase, the amount of carbon dioxide in the oceans also increases. The increased uptake of atmospheric carbon dioxide is resulting in chemical changes in the oceans, including a decrease in the average pH of surface ocean waters (making seawater more acidic) and a reduction in the availability of minerals needed by many marine organisms to build shells and skeletons, according to the National Research Council. These chemical changes, known as ocean

25Melillo, Richmond, and Yohe, Third National Climate Assessment. The primary greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere are water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone. 26National Research Council, Ocean Acidification: A National Strategy to Meet the Challenges of a Changing Ocean (Washington, D.C.: 2010). The National Research Council is now known as the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Climate Change Effects on Ocean Environments

Page 13 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

acidification, may pose risks for some marine species and ecosystems.27 For the purposes of this report, our discussion of the effects of climate change refers to both physical and chemical changes in the oceans.

Broadly defined, risk management is a strategic process for helping decision makers assess risk, allocate finite resources, and take action under conditions of uncertainty, such as when faced with incomplete information or unpredictable outcomes that may have negative impacts. Risk management is an inherent part of fisheries management, as fisheries managers often make decisions based on incomplete data and in the face of uncertainty. Accounting for the potential effects of climate change injects an additional source of uncertainty and risk into the fisheries management process. The federal government has recognized the need to account for climate change risks in its planning and programs and has called on agencies to take certain actions. For example, the President issued Executive Order 13653 in 2013, directing federal agencies to develop or update comprehensive climate change adaptation plans that among other things identify climate-related impacts on and risks to an agency’s ability to accomplish its missions, operations, and programs and describe the actions the agency will take to manage climate risks.28 Subsequently, the Department of Commerce’s 2014 Climate Change Adaptation Strategy set a goal to incorporate climate information in the department’s resource management programs and policies and to take action to reduce vulnerabilities and increase resilience of marine and coastal natural resources.29

We have previously reported on risk management in the context of climate change and identified risks that climate change may pose in a variety of areas relevant to the federal government, such as infrastructure

27See GAO, Ocean Acidification: Federal Response Under Way, but Actions Needed to Understand and Address Potential Impacts, GAO-14-736 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2014). 2878 Fed. Reg. 66,819 (Nov. 6, 2013). 29Department of Commerce, Department of Commerce Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (Washington, D.C.: 2014).

Risk Management as a Strategy for Managing Climate-Related Risks to Fisheries

Page 14 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

and federal supply chains.30 We found that leading risk management guidance recommends a sequence of activities that begins, in part, with identifying risks. Specifically, the International Organization for Standardization’s standards on risk management recommend that organizations such as federal agencies develop, implement, and continuously improve a framework for integrating risk management into their overall planning, management, reporting processes, and policies.31 These standards also state, among other things, that risk management should be a part of decision making and that it should be based on the best available information.

We found that NMFS and the Councils have general information about the types of effects climate change is likely to have on federally managed fish stocks, but information about the magnitude and timing of effects for specific fish stocks is limited, based on the responses NMFS and the Councils provided to our questionnaire, our analysis of NMFS and Council documentation, and our interviews with NMFS and Council officials. In addition, NMFS and the Councils identified several challenges they face to better understand the effects of climate change, such as determining the extent to which a change in a fish stock’s abundance or distribution is caused by climate change, natural variation in the oceans, or other human or environmental factors.

30See, for example, GAO, Climate Change: Future Federal Adaptation Efforts Could Better Support Local Infrastructure Decision Makers, GAO-13-242 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 12, 2013), and Federal Supply Chains: Opportunities to Improve the Management of Climate-Related Risks, GAO-16-32 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 13, 2015). 31International Organization for Standardization, ISO 31000 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines (2009). In addition, federal standards for internal control direct agencies to assess the risks they face from both external and internal sources, and to identify, analyze, and respond to relevant risks—including changes in external environmental conditions—associated with achieving agency objectives. See GAO/AIMD-00-21.3.1. We have revised and reissued our standards for internal control, with the new revision effective as of October 1, 2015. See GAO-14-704G.

NMFS and the Councils Have Limited Information on the Magnitude and Timing of Climate Change Effects on Fish Stocks

Page 15 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

Through our analysis, we found that NMFS and the Councils have general information about the types of effects climate change is likely to have on fish stocks, but information about the magnitude and timing of effects for specific fish stocks is limited. In general, the types of effects climate change is likely to have include changes in fish stock abundance and distribution and the timing or location of biological events such as spawning (the process by which fish reproduce), according to NMFS and Council officials. These effects will not be uniform across fish stocks but rather will likely vary, with the abundance of some stocks being negatively affected and the abundance of other stocks increasing or not being affected, according to NMFS documentation. Similarly, potential shifts in distribution will vary, as some fish stocks may respond to changing ocean temperatures by moving north or to deeper waters in search of the water temperatures they are accustomed to, but shifts in other directions may occur as well. Some NMFS and Council officials said that changes in the timing and location of biological events are also expected to vary between fish stocks. For example, some fish stocks may spawn at different times or in different locations under warmer ocean conditions.

In some instances, the abundance or distribution of fish stocks may shift in response to changes in ocean habitats occurring because of a changing climate. For example, reductions in seasonal sea ice cover and warmer ocean surface temperatures may open up new habitats in polar regions that could lead to shifts in distribution for some fish species, according to the 2014 Third National Climate Assessment. Furthermore, warming ocean temperatures and higher acidity levels also affect the health of coral reefs, which provide essential habitat for many fish stocks.32 The 2014 assessment reported, for example, that scientific research indicated that 75 percent of the world’s coral reefs were under threat from the effects of climate change and local stressors, such as overfishing, nutrient pollution, and disease. When water is too warm, corals will expel the algae living in their tissues, causing the coral to turn completely white—this phenomenon, known as coral bleaching, can cause coral to die or become more susceptible to disease, which can subsequently decrease their capacity to provide shelter and other resources for reef-dependent fish and other ocean life, according to the 2014 assessment.

32For additional information on the effects of higher ocean acidity levels, see GAO-14-736.

NMFS and the Councils Have Limited Information on the Magnitude and Timing of Climate Change Effects on Fish Stocks

Page 16 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

We found that NMFS and the Councils have limited scientific information about the magnitude and timing of potential climate change effects for most fish stocks they manage. For example, officials from one Council reported that they have very little scientific information specific to how climate change is currently affecting the fish stocks in their region, or how those stocks may be affected in the future, with the exception of some anecdotal information. NMFS and Council officials explained that scientific information is often lacking to quantify the magnitude and timing of effects for most individual fish stocks and that their ability to project future effects at the stock level is generally limited. For instance, NMFS and Council officials in the Alaska region reported that they have information sufficient to project potential climate change effects on abundance for 3 of the 35 primary fish stocks they manage in their region.33 And, as reflected in the examples below, for those stocks where they are able to project potential effects, they are uncertain about the full range of effects those stocks might experience.

• Northern rock sole. NMFS officials in the Alaska region said that their research on northern rock sole has shown that the juvenile fish may have increased odds of surviving to become adults under warmer ocean conditions, which could have a positive effect on their abundance. NMFS officials said that the research indicates that northern rock sole can adjust their diets to survive in a variety of habitats and therefore may be able to adapt to ecosystem changes such as warming ocean temperatures more easily than other fish species. In general, NMFS and Council officials from the Alaska region said that they do not anticipate the effects of climate change on the abundance of northern rock sole to be significant, but acknowledged that it is unknown how warming ocean conditions may affect the timing or location of the fish’s life cycle events, such as spawning.

33The three fish stocks are northern rock sole, red king crab, and walleye pollock. The NMFS Alaska region has several efforts under way to better understand the effects of climate change on the fish stocks it manages in the region, including research projects and evaluations of potential fisheries management strategies that could be used under changing ocean conditions, according to agency officials.

Northern Rock Sole The northern rock sole is a flatfish with both eyes on one side of its head. Northern rock sole live on the ocean floor and prefer a sandy or gravel ocean bottom. In the United States, northern rock sole are found from the Puget Sound through the Bering Sea and the Aleutian Islands. Northern rock sole are cooperatively managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Alaska region and the North Pacific Fishery Management Council. In 2014, the commercial harvest for the rock sole fishery (which includes northern rock sole and southern rock sole) was valued at approximately $18.2 million, according to NMFS data.

Sources: NMFS documentation (text); http://www.fishwatch.gov/ (image). | GAO-16-827

Page 17 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

• Walleye pollock. NMFS officials in the Alaska region said that they can project some future effects of warming ocean temperatures on the abundance of walleye pollock. For instance, the officials told us that research indicates warming ocean temperatures could lead to a mismatch between the size of the pollock population and the availability of food sources for pollock to consume. Unusually warm winters in the Alaska region in the early 2000s caused seasonal ice to retreat earlier and farther than normal, which led to reductions in the amount of zooplankton available for young pollock to eat, according to NMFS officials. When young fish do not have sufficient food in their first year of life, the likelihood they will survive is reduced, and according to NMFS officials, the reduction in zooplankton led to a reduction in the pollock population. The officials did not attribute the warmer ocean temperatures during this time to climate change, but they said this event helped them forecast potential future climate effects by providing an opportunity to observe how pollock respond to changes in the environment similar to those anticipated from climate change. However, NMFS officials we interviewed said that making further predictions about the magnitude of potential climate change effects on the abundance and distribution of pollock is difficult because of the limited amount of climate-related information specific to the species. Agency officials told us that additional research is under way to better understand the effects of warmer ocean temperatures on pollock.

To better understand which fish species may be most vulnerable to climate change, NMFS initiated an effort to systematically assess the vulnerability of marine species to a changing climate. Specifically, in 2015, NMFS developed a methodology for conducting climate vulnerability assessments for marine species using a combination of quantitative data, qualitative information, and expert opinion. The agency has used this methodology to complete an assessment for marine fish and invertebrate species that commonly occur in the Greater Atlantic region, which it published in February 2016.34 As of August 2016, NMFS

34Jonathan A. Hare et al., “A Vulnerability Assessment of Fish and Invertebrates to Climate Change on the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf,” PLOS One, vol. 11, no. 2 (2016). Invertebrates are species that do not have a backbone, including shellfish such as lobsters and crabs. Since this assessment was performed at the species level, the results for an individual species may apply to multiple fish stocks in instances where a species is managed as more than one stock. The results of this assessment are not generalizable to all fish and invertebrate species in this region or elsewhere.

Walleye Pollock Walleye pollock are a member of the cod family and have a speckled coloring that helps them blend with the seafloor to avoid predation. They are a schooling fish distributed broadly in the North Pacific Ocean and in the Bering Sea, with the largest concentrations in the United States being found in the eastern Bering Sea. Walleye pollock are cooperatively managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Alaska region and the North Pacific Fishery Management Council. The pollock fishery is the largest commercial fishery by volume in the United States, and in 2014, its commercial harvest was valued at approximately $399.9 million, according to NMFS data.

Sources: NMFS documentation (text); http://www.fishwatch.gov/ (image). | GAO-16-827

Page 18 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

had climate vulnerability assessments under way for species in its other four regions, according to agency officials.35 The assessment in the Greater Atlantic region found that approximately half of the 82 species assessed in the region were estimated to have a high or very high vulnerability to climate change, with the other half having low or moderate vulnerability.36 The assessment defined climate vulnerability as the extent to which the abundance or productivity of a species could be affected by climate change and natural long-term variability in ocean conditions.37 Similarly, more than half of the species were estimated to have a high or very high potential to shift their distribution in response to projected changes in the climate. The assessment also provided a summary of the existing scientific knowledge about the expected effects on different species in the region but did not quantify the magnitude of the expected effects for individual species. NMFS officials told us that the assessment was not designed to provide that type of quantitative information. Instead, the officials said the information provided by the assessments could be used to help determine which species should be the subject of additional research to help quantify potential climate effects in the future. The vulnerability assessment completed in the Greater Atlantic region provides illustrations of the range of ways that species may be affected by climate change, as reflected in the following examples.

35The officials said that they expect to publish the results of these assessments in 2017 or 2018, depending on the region. 36The assessment noted that the level of certainty for the estimates of species’ climate vulnerability varied between species, ranging from very high to low. The assessment generally focused on modeled changes in surface ocean conditions (i.e., changes in the upper 10 meters of the ocean). Changes in bottom ocean conditions are not as well understood, but may be important for some bottom-dwelling species, according to NMFS officials. 37The assessment estimated that some vulnerable species will be negatively affected by climate change and that others will experience neutral or positive effects.

Page 19 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

• Atlantic cod. According to the NMFS climate vulnerability assessment, the abundance of Atlantic cod is likely to be negatively affected by warming ocean temperatures in the Northeast. Specifically, the assessment indicated that warmer ocean temperatures may be linked with a lower number of juvenile cod that survive and grow to a size sufficient to enter the fishery each year. The assessment also found that continued ocean warming could produce less-favorable habitat conditions for cod in the southern end of its range. Atlantic cod have experienced a decline in abundance in recent decades, and warming ocean temperatures may have contributed to this decline, according to NMFS and Council officials in the Greater Atlantic region. The officials further indicated, however, that the extent to which changing temperatures played a role in the cod decline is unclear because it is difficult to isolate this factor from other contributing factors, such as overfishing.38

38As a result of the decline in abundance of Atlantic cod and other groundfish stocks in the Northeast, the Department of Commerce determined in 2012 that a commercial fishery failure had occurred in the Northeast Multispecies Groundfish Fishery. In fiscal year 2014, Congress appropriated $75 million for fishery disaster assistance in the United States, and NMFS obligated $32.8 million of that amount for the declared fishery disaster in the Northeast Multispecies Groundfish Fishery. Groundfish are fish that live on, in, or near the bottom of the body of water they inhabit. Thirteen groundfish species are managed under the Northeast Multispecies Groundfish Fishery, including Atlantic cod, Atlantic halibut, and yellowtail flounder.

Atlantic Cod Atlantic cod have a large head, blunt snout, and a distinct barbel (a whisker-like organ, like on a catfish) under the lower jaw. Cod live near the ocean floor along rocky slopes and ledges and prefer to live in cold water. In the United States, cod range from the Gulf of Maine to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, and are most commonly found off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and in the western Gulf of Maine. Cod are cooperatively managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Greater Atlantic region and the New England Fishery Management Council. In 2014, the Atlantic cod commercial harvest was valued at approximately $9.4 million, according to NMFS data. Atlantic cod have been an important commercial fish stock based on the historical volume and value of the fish caught in the Northeast.

Sources: NMFS documentation (text); http://www.fishwatch.gov/ (image). | GAO-16-827

Page 20 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

• Black sea bass. The distribution of the northern stock of black sea bass, historically found in the Mid-Atlantic, has shifted northward in recent decades, according to NMFS officials in the Greater Atlantic region. This trend is likely to continue as ocean temperatures warm and become more favorable for the fish, according to the NMFS climate vulnerability assessment. The assessment also indicated that the abundance of black sea bass in more northern areas will likely increase as temperatures warm and more spawning occurs. According to NMFS and Council officials and other fisheries stakeholders, changes in the abundance and distribution of black sea bass could present a challenge for fisheries managers because commercial fishing rights have been allocated to states based on historical catch data that may not reflect where the fish are found in the future.

Black Sea Bass Black sea bass are usually black with a slightly paler belly and a dorsal fin that is marked with a series of white spots and bands. Black sea bass commonly inhabit rock bottoms near pilings, wrecks, and jetties. Along the East Coast, black sea bass are divided into two fish stocks for management purposes. The stock found north of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, is cooperatively managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Greater Atlantic region, the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. The southern stock is cooperatively managed by NMFS, the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council, and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. In 2014, the black sea bass commercial harvest was valued at approximately $8.6 million, according to NMFS data.

Sources: NMFS and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission documentation (text); http://www.fishwatch.gov/ (image). | GAO-16-827

Page 21 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

• American lobster. The overall effect of climate change on lobster abundance is estimated to be neutral, as population decreases in the southern portion of its range have been offset by increases in the north, according to the NMFS climate vulnerability assessment. NMFS officials in the Greater Atlantic region said that these population changes are believed to be driven in large part by warming ocean temperatures. Specifically, officials said that as ocean conditions in southern New England have become less favorable to lobsters because of increasing ocean temperatures, the abundance of the southern stock has declined.39 In contrast, the abundance of the northern stock has increased as temperature changes in the Gulf of Maine (where waters are generally colder) have produced more favorable conditions for lobster. NMFS has not been able to quantify the magnitude of expected future changes in lobster abundance in the region, however, in part because it is difficult to accurately forecast changes in ocean temperatures more than a few months out, according to agency officials. Additionally, NMFS officials indicated that changing ocean conditions can affect the timing of biological events in the lobster’s life cycle, which may subsequently alter the seasonal abundance of the stocks in a way that may cause disruptions to the fishing industry. For instance, in 2012, warmer-than-usual ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Maine resulted in American lobsters growing to market size earlier than usual, according to NMFS documentation. As a result, lobsters were harvested early, but some lobster processing facilities were not yet ready to receive them, which led to an abundance of supply for the fishermen and a drop in the market price they received for their harvest.

39In response to declining lobster populations in southern New England, in recent years the Secretary of Commerce has issued a number of regulations and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission has imposed measures, such as closed seasons in certain areas, more stringent standards about the size of harvestable lobsters, and reductions in the number of traps allowed for harvesting.

American Lobster The American lobster is a crustacean with a large shrimp-like body with eight legs and two claws. Lobster live on the ocean floor and are most abundant in coastal waters from Maine through New Jersey, and offshore from Maine through North Carolina. The lobster fishery has northern and southern stocks that are cooperatively managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Greater Atlantic region and the member states of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. In 2014, lobster’s commercial harvest was valued at approximately $567.3 million, which made it one of the most economically valuable fisheries in the country that year, according to NMFS data.

Sources: NMFS and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission documentation (text); http://www.fishwatch.gov/ (image). | GAO-16-827

Page 22 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

Through the questionnaire responses and our interviews, NMFS and Council officials identified several challenges to better understand the existing and anticipated effects of climate change on fish stocks as well as efforts they are taking to address some of these challenges, including:

• Understanding how climate change may affect fish stocks. NMFS and most of the Councils indicated that a significant challenge they face is better understanding the relationship between changes in ocean conditions and the processes that drive how fish will react to those changes. NMFS officials explained that it can be difficult, for instance, to understand how water temperature changes may affect the biology of specific fish stocks or may indirectly affect their habitat and interactions with other species within that habitat. Officials from one NMFS region said that they do not have a sufficient understanding of the processes that drive fish stock productivity—including their birth, growth, and death rates—in their region, or how those processes may be affected by climate change. Officials from several other NMFS regions and Councils shared similar views and noted that this challenge limits their ability to understand the overall effects that climate change may have on different fish stocks.

• Availability of baseline data. NMFS and several of the Councils reported that insufficient baseline data at times limit their ability to predict the effects of various changes in the climate on fish stocks. Baseline data include oceanographic information, such as water temperature in different regions and depths; information about a fish stock, such as temperature preference and spawning history; and ecological information, such as the type of plants or animals available as a food source for a particular stock or its role in a food web. For example, NMFS officials told us that sea surface temperature data are widely available in most regions but that data on subsurface temperatures are limited. The officials attributed the difference in the availability of these two types of data to the ability to use satellites to measure sea surface temperatures, whereas the collection of subsurface temperature data is more difficult and requires measurements to be taken directly from the ocean. NMFS officials said that the lack of subsurface temperature data limits their ability to research and determine potential effects of changing temperatures on bottom-dwelling fish stocks, such as the American lobster. The officials told us that NOAA has increased its efforts to utilize technologies such as ocean gliders—autonomous underwater vehicles used to collect ocean data—to track subsurface ocean conditions and collect additional baseline data. For example, in 2014 NOAA partnered with other scientists to launch two ocean gliders in

NMFS and the Councils Identified Several Challenges to Better Understand the Effects of Climate Change on Fish Stocks

Page 23 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

the Gulf of Alaska to collect data for 5 months on water temperature, salinity, and dissolved oxygen, among other things.

• Distinguishing between climate change and other factors. It can be challenging to determine whether a change in a fish stock’s abundance or distribution is caused by climate change; natural variation in the oceans; or other human or environmental factors, such as overfishing or pollution, according to NMFS and some Council officials. Isolating the effects of climate change from other factors is difficult, and the complexities of trying to understand the ways in which these factors interact also present challenges, according to the officials. For example, NMFS officials in the Greater Atlantic region said that populations of summer flounder have increased in recent years after experiencing significant declines from overfishing in the 1970s and 1980s, and that summer flounder are being found in greater numbers in northern areas, such as the Gulf of Maine. The officials said that changes in fishing levels are likely driving the increase in summer flounder abundance and their increased presence in northern areas, but also suggested that warming ocean temperatures may have played a role.

• Modeling capabilities. NMFS and most of the Councils identified limitations in climate and fisheries modeling capabilities as a challenge to better understand the effects of climate change on fisheries. For example, according to NMFS officials, one important step to improving the ability to project the effects of climate change on specific fish stocks will be to downscale global ocean climate models, such as models of changes in ocean temperatures, to more regional and local levels that can then be used to assess climate effects on the fish stocks that inhabit those locations.40 Agency officials described this type of information as foundational knowledge that is generally not yet available across the NMFS regions, in part because it is resource intensive to develop. The officials said that NMFS considers the development of downscaled climate models that can be used to support fisheries management to be a critical need, and that efforts are under way to develop such models in some NMFS regions. For example, NMFS is funding a project to help downscale global climate models for some of the major rivers and estuaries in the Northeast,

40In this context, downscaling involves, among other things, adding finer spatial detail to global climate models of projected changes in ocean conditions.

Summer Flounder Summer flounder are flatfish, with both eyes located on the left side of the body when viewed from above, with the dorsal fin facing up. Adult summer flounder spend most of their lives on or near the seafloor, burrowing into the sand. In the United States, summer flounder are found from the Gulf of Maine through North Carolina. The stock is cooperatively managed by the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Greater Atlantic region, the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. Summer flounder are one of the most sought after commercial and recreational fish along the Atlantic coast, and in 2014, the commercial harvest was valued at approximately $32.3 million, according to NMFS data.

Sources: NMFS, Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission documentation (text); http://www.fishwatch.gov/ (image). | GAO-16-827

Page 24 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

such as the Chesapeake Bay, that are crucial habitats for many commercial, recreational, and protected species.

• Resources. NMFS and most of the Councils identified constrained resources as a challenge to expanding climate-related data collection and analysis efforts. For instance, according to NMFS officials at one Fisheries Science Center, developing climate science for fisheries management requires extensive new modeling to assess and project current and future fishery conditions, including how fish stock abundance and distribution may change under changing physical and chemical ocean conditions. However, the officials said that staff capacity to conduct this work is limited because of existing modeling demands for stock assessments. Similarly, officials from one Council told us that additional staff and resources would be required to incorporate climate-related information into their work.

NMFS has developed a strategy to help it and the Councils incorporate climate information—such as information on changes in ocean temperatures and acidity levels and the risks to fish stocks associated with those changes—into the fisheries management process, but is in the early stages of implementing the strategy. Through our analysis, we found that NMFS and the Councils have generally not incorporated climate information into the fisheries management process to date because the information they have on the effects of climate change on most fish stocks has not been sufficient. However, recognizing the importance of further developing climate information and incorporating it into the fisheries management process, NMFS published its NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy in August 2015.41 The Strategy is intended to support efforts by the agency and its partners to increase the production, delivery, and use of climate information in managing fish and other living marine resources. According to the Strategy, failing to adequately incorporate climate change considerations into fisheries management and conservation efforts could cause those efforts to be ineffective, produce negative results, or miss opportunities. Determining how information on the effects of climate change can be incorporated into

41Link, Griffis, and Busch, NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy. The Strategy applies to all of the living marine resources under NMFS’ responsibility, including federally managed fish and shellfish, protected marine mammals, and species listed as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

NMFS Developed a Strategy to Help Incorporate Climate Information into Fisheries Management, but It Is in the Early Stages of Implementation

Page 25 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

the fisheries management process is a key question that NMFS must address, according to the Strategy.

The Strategy lays out a national framework that is to be regionally tailored and implemented. NMFS officials said that the agency’s regions (including its regional offices and regional Fisheries Science Centers) will have primary responsibility for implementing the Strategy, and those offices are in the process of developing regional action plans to describe how they will do so. NMFS has directed its regions to develop regional action plans that identify specific actions each region will take over the next 5 years to implement the Strategy and include the region’s assessment of its priorities and available resources, among other things. As of July 2016, four of NMFS’ five regions had released draft versions of their regional action plans for public comment, and agency officials said that they expect all of the regions to finalize their plans by October 2016. The officials said that NMFS headquarters has provided input on the draft plans and will work with the NMFS Science Board to review and approve the final plans.42

The Strategy recognizes the importance of incorporating climate information into the fisheries management process but does not provide specific guidance on how this is to be done. For example, the Strategy notes the importance of factoring climate information into stock assessments but does not include specific guidance on how such information should be incorporated into developing the assessments. Historically, fish stock assessments primarily considered the effects of fishing when estimating the abundance of individual fish stocks and have not accounted for ecosystem factors, including effects from changes in the climate. This traditional approach has been effective for assessing present and historical abundance levels but may not be effective in forecasting future levels because it does not account for effects related to changing environmental conditions, according to NMFS documentation. NMFS and Council officials said that factoring climate information more widely into stock assessments in the future will be important, given the changing climate conditions and particularly because stock assessments often provide the scientific basis for management decisions, including

42The NMFS Science Board is made up of the NMFS Chief Science Advisor, the Director of Science and Technology, and the science directors from each of the regional Fisheries Science Centers.

Page 26 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

setting annual catch limits. The Strategy also states that including climate-related data to inform reference points (the limits or targets used to guide management decisions), where appropriate, is critical to avoid misaligned management targets for fish stocks, but the Strategy does not provide specific guidance on how this is to be done. In addition, the Strategy calls for NMFS to complete climate vulnerability assessments for all regions as an initial priority action but does not specify how NMFS regions and the Councils should use the results of the assessments to inform management decisions or incorporate them into the fisheries management process.43

Without developing guidance on how climate information is to be incorporated into specific aspects of the fisheries management process, NMFS does not have reasonable assurance that all of its regions and the Councils will consistently factor climate-related risks into fisheries management. Under federal standards for internal control, agencies are to clearly document internal controls, and the documentation is to appear in management directives, administrative policies, or operating manuals.44 In addition, according to the International Organization for Standardization, for risk management to be effective, it is important for information on risks to be included as a part of decision making.45 Moreover, developing guidance would be consistent with actions NMFS has taken for other parts of its mission, according to the agency’s Climate Change Coordinator. The official noted that in January 2016, NMFS developed guidance on using climate change information in the agency’s Endangered Species Act decisions, which could serve as a model for the fisheries management process.46 The guidance provides direction on how climate information should be incorporated into Endangered Species Act

43The Strategy states that these assessments are important tools to help identify species at higher risk in a changing climate, as well as some reasons for these risks and key information needs to better understand the risks. 44GAO/AIMD-00-21.3.1. We have revised and reissued our standards for internal control, with the new revision effective as of October 1, 2015. See GAO-14-704G. 45See International Organization for Standardization, ISO 31000 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines (2009). 46NMFS subsequently revised this guidance in June 2016. See National Marine Fisheries Service, Revised Guidance for Treatment of Climate Change in NMFS Endangered Species Act Decisions, NMFS Memorandum (Silver Spring, Md: June 17, 2016).

Page 27 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

management decisions and what types of climate information should be used, among other things. NMFS has not yet developed similar guidance for fisheries management because doing so was not previously considered to be an immediate priority given the agency’s limited information on the anticipated effects of climate change on fish stocks and the near-term focus of most fisheries management decisions, according to NMFS’ Climate Change Coordinator. The official said, however, that as knowledge about the effects of climate change on fisheries has progressed over time, NMFS has found an increased and more pressing need to begin preparing for these effects in the near term. By developing guidance on how the NMFS regions and Councils are to incorporate climate information into different parts of the fisheries management process, NMFS may help ensure consistency in how its regions and the Councils factor climate-related risks into fisheries management decision making.

In addition, the Strategy lays out overall objectives to help identify the agency’s climate information needs and help better ensure effective management in a changing climate, but does not contain agency-wide performance measures to track progress in achieving the Strategy’s objectives. Specifically, the Strategy lays out seven interrelated, priority objectives (see table 1).

Page 28 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

Table 1: NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy (Strategy) Priority Objectives

Objective Description Identify reference points for managing living marine resources that appropriately incorporate climate information

The Strategy describes reference points as the thresholds upon which living marine resource management decisions are made, and cites the importance of incorporating climate information into reference points as a critical part of responding to the effects of climate change on fisheries.

Identify robust strategies for managing living marine resources under changing climate conditions

The Strategy calls for NMFS to help identify management strategies that will be effective under a wide range of future ocean conditions and to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of alternative approaches to managing living marine resources in the face of a changing climate.

Design adaptive decision processes that can incorporate and respond to changing climate conditions

This objective focuses on, among other things, developing fisheries management decision processes that are adaptive and flexible under changing conditions and identifying where and how climate information could best be incorporated into those processes.

Identify future states of ecosystems, living marine resources, and the human communities that depend on them in a changing climate

In this objective, the Strategy cites the importance of developing robust, model-based projections of future ocean conditions and the ways in which changing conditions will affect ecosystems (marine, coastal, and freshwater), living marine resources, and human communities.

Identify the mechanisms of climate change impacts on ecosystems, living marine resources, and the human communities that depend on them

The Strategy calls for steps to be taken, such as conducting research and vulnerability assessments, to, among other things, better understand how and why climate change can affect ecosystems, living marine resources, and dependent human communities, and to help identify species at higher risk in a changing climate.

Track trends in ecosystems, living marine resources, and the human communities that depend on them and provide early warning of change

This objective focuses on the importance of (1) monitoring the characteristics of marine and coastal ecosystems, living marine resources, and human communities; (2) developing physical, biological, and socioeconomic indicators for tracking trends related to climate change and for providing early warning of climate change impacts; and (3) regularly reporting on climate-related monitoring data and indicators, such as through ecosystem status reports.

Build and maintain the science infrastructure needed to fulfill NMFS’ mandates (such as its responsibilities under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976, as amended) under changing climate conditions

The Strategy cites the need to improve, and in some cases expand, NMFS’ scientific infrastructure—including staffing, computing systems, and partnerships with entities such as state agencies and academia—to successfully implement the Strategy.

Legend: NMFS: National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Source: GAO analysis of the NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy. | GAO-16-827

According to NMFS officials, the agency recognizes the potential benefit of developing a comprehensive set of agency-wide performance measures for the Strategy, but it has not specified when or how it may do so because it is first focusing on completing the regional action plans. NMFS has directed its regions to include performance measures in their regional action plans outlining how they will implement the Strategy, and agency officials told us that once the regional action plans are finalized in October 2016, NMFS plans to revisit whether to develop agency-wide

Page 29 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

performance measures for the Strategy. We have previously reported on the importance of agencies using performance measures to track progress in achieving their goals and to inform management decisions.47 Moreover, the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993, as amended, requires federal agencies to establish performance goals and related performance measures to track progress in annual agency performance plans, among other things.48 While these requirements apply at the departmental level (e.g., Department of Commerce), we have previously found that they also serve as leading practices in component agencies, such as at NMFS, to assist with planning for individual programs or initiatives that are particularly challenging.49 This is also in line with federal standards for internal control, which identify the establishment and review of performance measures as a control activity that can help ensure that management’s directives are carried out and that actions are taken to address risks, among other things.50

According to NMFS guidance, the regional action plans are to identify performance measures to document progress in implementing the Strategy at the regional level. In reviewing the four draft regional action plans that had been released as of July 2016, we found that three of the draft plans contained proposed performance measures. Specifically, we found that the measures each of the three regions proposed included some key attributes of successful performance measures that we have previously identified, such as being aligned with the Strategy’s objectives and having limited overlap (see app. II for the full list of key attributes).51 However, most of the measures did not contain other key attributes. For

47For example, see GAO, Managing for Results: Enhancing Agency Use of Performance Information for Management Decision Making, GAO-05-927 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 9, 2005), and GAO-16-131. 4831 U.S.C. § 1115(b). 49For example, see GAO-16-131. In addition, we have previously found that leading public sector organizations seek to establish clear hierarchies of performance goals and measures that link the goals and measures for each organizational level to successive levels, and that doing so can help federal agencies successfully measure their performance. See GAO/GGD-96-118 and GAO/GGD/AIMD-10.1.18. 50GAO/AIMD-00-21.3.1. We have revised and reissued our standards for internal control, with the new revision effective as of October 1, 2015. See GAO-14-704G. 51For more information on the key attributes, see GAO-03-143.

Page 30 GAO-16-827 Federal Fisheries Management

example, nearly all of the proposed measures contained in the three draft plans did not include measurable targets, another key attribute of successful performance measures. In some cases, the proposed measures identified quantitative data to be tracked—such as the number of stock assessments or annual catch limits that include climate information—but there were no numerical targets identified that could serve as a means for assessing progress. We have previously found that including measurable targets in performance measures helps in assessing whether performance is meeting expectations.52 NMFS officials said that they recognized the importance of developing meaningful performance measures. By incorporating key attributes associated with successful performance measures in the final performance measures developed for the plans and assessing whether agency-wide performance measures may also be needed, NMFS may be in a better position to determine the extent to which the objectives of the Strategy overall are being achieved.