Fusarium Wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. elaeidis In Oil ...€¦ · In Oil Palm: A Rather Weak...

Transcript of Fusarium Wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. elaeidis In Oil ...€¦ · In Oil Palm: A Rather Weak...

-

Fusarium Wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. elaeidis)

In Oil Palm: A Rather Weak Pathogen?

C.Ml. Chinchilla*

Introduction

Fusarium wilt in oil palm (Fusarium oxyspo-rum f. sp. elaedis) was initially described byWardlaw in Zaire (Wardlaw 1946). The patho-gen has been associated with important lossesin some orchards (15-25 %) in Central andWest Africa, but average incidence for thewhole continent may be well below 1%(G.Blaak, former FAO official, personalcommunication), despite the poor agronomicmanagement frequently found on Africanplantations. In America, the pathogen hasbeen reported from Para (Brazil) and Quinindé(Ecuador) (Turner 1970; Van de Lande 1985;Renard and Franqueville 1989; Franquevilleand Renard 1990, Mariau et al. 1992; Franque-ville and Diabaté 2004).

Apart from the initial reports of the pre-sence of the disease in some plots of a fewplantations in the above-mentioned two coun-tries in America, no further information hasbeen published on any important economicimpact on oil palm plantations where thepathogen was found. It even looks as thoughthere was little spread beyond the originalspots where the first infected plants werefound, indicating the very low aggressivenessof this pathogen, at least in the American tro-pics. It is normally assumed that the fungusreached America from Africa via infectedseeds or in contaminated leguminous seedsused as cover crops in most oil palm planta-tions (Franqueville and Diabaté 2004).

Symptoms

There is great variation in incidence andsymptom expression depending on the tole-rance of the planting material, its age and parti-cularly on environmental conditions and agro-nomic management (Wardlaw 1950; Renard1979; Renard and Franqueville 1989).

When symptoms are severe (acute) in adultpalms, these may die within a few months:older leaves dry out and their rachises breakapproximately one third from the base andremain hanging beside the stem. The youngestleaves turn yellow and are shorter than normal.Characteristic of the pathogen's presence isthe brown color assumed by the vascularfibers. These darker fibers are more conspi-cuous at the base of the stem where the colormay be accentuated in some areas toward theperiphery. The radical system looks severely

deteriorated, particularly the finest roots thatshow an internal browning.

Nevertheless, symptoms may also becomechronic and infected palms may even showclear signs of recovery. This response may beinterpreted as the planting material's toleranceor particular environmental conditions (wateravailability, soil characteristics, plant nutri-tion etc.) that impede the pathogen from con-tinuing on an aggressive path of infection.Some palms suffering chronic symptoms for along time may show a stem tapering with age.

Symptoms normally vary in young palms:initially, a particular leaf located in the middleof the crown turns lemon-yellow, followed byother middle-aged neighbor leaves soon after.Older leaves eventually show symptoms con-sisting of yellowing that turns brown starting

ASD Oil Palm Papers, N°36, 34-44. 2011

* Consultor para ASD Costa Rica P.O. Box 30-1000, San José, Costa Rica. [email protected]

-

with the leaflets' tips. Such symptoms tend tobe more conspicuous toward the end of rainyperiods indicating the strong enviromentaleffect on symptom expression. Due to the dis-tribution of the infected vascular bundles ofthe palms, symptoms are normally only seenon one side of the plant (Wardlaw 1950) (Fig.1).

In a cross section of the stem, vascularfibers in particular sections appear discolored(first orange, then reddish-brown and finallyblack) (Fig. 2). The petiole of an affected leafalso shows discolored vascular bundles. Palmsso affected may die or enter the chronic phaseof the disease (with the fungus remaininglatent in the vascular tissue), where new leavesproduced are shorter and palm growth is nor-mally retarded.

Infection may take place at the nurserystage, causing retarded growth, short andsomewhat deformed leaves (flat-top appea-rance) and an abnormally swollen bulb (Fig. 3).Roots are few and affected (particularly fineroots), all showing a clear infection that pro-gresses toward the bulb where vascularbundles show an orange coloration that chan-ges to black (Prendergast 1957, 1973; Lockeand Colhoun 1974; Aderumgboye 1980, Chin-chilla, 1986).

External and internal symptoms are causedby a blocking of the xylem vessels by tylosesand gum deposits that interrupt normal waterflow. Filaments and other fungal structures(microconidia and chlamydospores) may alsobe found in the vessels (Aderumboye 1982;Kobachich 1984).

Epidemiology or, how effective apathogen is it?

F. oxysporum f. sp. elaeidis may survive in thesoil as a saprophyte or in contact with the rootsof several weeds, 'waiting' for an occasion togain access to an oil palm root and initiate aninfection. Any factor causing root death (andquite possible any limitation for normal rootdevelopment) may offer an opportunity for thefungus to enter the palm (Aderungboye 1982;Lockey and Colhoun 1974). Root penetration

may also take place through the pneumatodes,which are more numerous when soil is wet(possibly too wet); this may explain theincrease in incidence toward the end of therainy season (when root death also increasesdue to poor soil aeration). An increase in inci-dence during the start of the rainy season mayalso be explained by root death during the pre-ceding dry season (water deficit).

Pathogenic strains of the fungus have beenfound in areas where oil palm had never beenplanted before (Aderungboye 1982). On theother hand, Hoo and Varghese (1987) compa-red several Malaysian native isolates of F.oxys-porum with virulent strains of F. oxysporum f.sp.elaeidis obtained from Africa and found thatgrowth in culture media, morphology, coni-diogenesis, and the effect of temperature andrelative moisture on growth were identical forthe two origins. More interesting is the factthat some strains of Fusarium oxysporum, consi-dered non-pathogenic and native from soils inMalaysia were able to cause wilting and growthretardation in nursery plants (Hoo andVarghese 1986; Flood et al. 1989). Theseobservations could be interpreted as a latentdanger of many strains of Fusarium becomingpathogenic to oil palm, or as casting importantdoubts on the real pathogenic potential ofthese particular strains of Fusarium, includingthose associated with Fusarium wilt in Africa.

Germination of chlamydospores (fungalsoil survival structures) is stimulated in theneighborhood (rhyzosphere) of roots of bothsusceptible and non-susceptible plants (suchas corn). This was interpreted as if tolerance tothe pathogen was posterior to germination(Oritsejafor 1990), but there could be othercauses for that. The phenomenon of cross pro-tection has also been observed: a previousinfection by a mild strain prevents infection bya more aggressive one (IRHO, 1992).

There is evidence that the fungus can becarried in the oil palm seeds and can evenaccompany pollen (Locke and Colhoun 1973;Flood et al. 1990). Once established in the soil,the fungus may remain there for years associa-ted with roots of several asymptomatic weedspecies such as Amaranthus spinosus, Eupatorium

ASD Oil Palm Papers, N° 36, 2011

35

-

odoratum, Mariscus alternifolius and Imperata cylin-drica (Oritsejafor 1986). All these plants can becommon in some oil palm plantations.

Eradication of diseased palms was not ini-tially considered a valid control measureoption (Prendergast 1957), but this was notalways clear since there was a high correlationbetween the percentage of diseased palms leftstanding and disease incidence after replanting(Renard and Franqueville 1991).

Diseased palms may occur isolated or ingroups within the orchard. The closer a palm isplanted to a site where another palm showedsymptoms, the higher the chance that the newplant will become diseased: a mere two meterdistance from a place where a palm died fromthe disease may reduce the probability that thenew palm would become infected by 50%(Renard and Franqueville 1991).

Since the disease progression over time (1-2% per year, Renard 1979) is rather low even invery susceptible materials (and quite probably,poorly managed plantations); yield effect onthe whole orchard is also low, particularlywhen affected palms are eradicated early,allowing healthy neighbor palms to compen-sate yield (no yield effect was noted below 20%incidence). Good agronomic management willno doubt more than compensate any missingpalms. It can easily be concluded that yieldeffect will be minimized by using proper agro-nomic practices, and no doubt, stress tolerantvarieties (Franqueville and Renard 1990). Astrong environmental effect (climate, nutri-tion, soils, etc.) on disease incidence and seve-rity has been documented (Aderungboye 1982;Ollagnier and Renard 1976; Prendergast 1957;Renard and Quillec 1983; Oritsejafor 1986;Renard and Franqueville 1991). Some exam-ples are:

� Incidence increases after prolonged dry periods.Disease becomes more prevalent in places withsuch prolonged dry spells in West Africa. Thenegative effects of water deficit are enhancedwhen temperatures are abnormally high, potas-sium is deficient and the soil has a low water hol-ding capacity. All these effects will cause massivedeath of the root system which is very superficialin oil palm.

� Poor soil aeration (which also causes root death)is associated with higher incidence. Poor soilaeration can be caused by lack of a proper drai-nage system, soil compaction, very fine textures,etc.

� Incidence (and probably symptom expression)increases in palms receiving no fertilizer or anunbalanced formula; particularly excesses ofnitrogen in the absence of proper amounts ofpotassium. Inadequate nutrition of oil palm(amount, frequency, and balanced) in a large pro-portion of West Africa oil palm orchards is cer-tainly a common denominator. This situation isaggravated in soils that are naturally low in ferti-lity.

� Incidence tends to be higher where soil texture islight (high sand content), pH is low and organicmatter content is also low.

Genetic Tolerance

There was an ample response in terms oftolerance between planting materials (Ollag-nier and Renard 1976, Franqueville andRenard 1990). It has to be kept in mind thatmany orchards in Africa used native dura mate-rials with no formal breeding. Some newerplanting materials are recognized by their tole-rance to abiotic stress which no doubt is rela-ted to tolerance to diseases like Fusarium wiltthat are closely associated with stress condi-tions such as water deficit, water logging andinadequate nutrition. It is fascinating thatsome oleifera palms evaluated also showed tole-rance to Fusarium wilt: stress tolerant materialsand oleifera and its hybrids with guineensis tendto be also tolerant to spear rots.

Breeding for tolerance is rather easy consi-dering that tolerance at the nursery stageseems to be related to field tolerance. Inocula-tion methods have been developed which per-mit selection of the most promising crosses inthe nursery stage (Franqueville 1984; Prender-gast 1963; Renard et al. 1980; Renard et al.1972; Chinchilla 1987; Franqueville andRenard 1990). Nevertheless, disease suscepti-bility seems to be associated with many genes(some associated with stress tolerance?),which precludes the possibility of obtainingcompletely resistant progenies (Prendergast1963).

36

-

Conclusions

Consulting the available literature, talkingto people who are familiar with the disease,and knowing that there are poor agronomicmanagement conditions on a large percentageof oil palm plantations in Africa (many are justwild dura materials), makes it difficult to avoidconcluding that Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. elaei-dis is a rather weak and opportunistic pathogenin oil palm.

Considering the many weaknesses of thispathogen documented in the literature andsummarized above, is also safe to concludethat choosing planting sites with no clear limi-tations for oil palm growing and giving a fairagronomic management will prevent thedisease from gaining any economic impor-tance. Some obvious practices that must befollowed in sites where there is some risk ofFusarium wilt causing problems are intended to

reduce water deficit (dry season) and excesses(particularly during the last months of therainy season). Examples of these practices are:

1 Using the best nursery plants.

2 Planting early in the rainy season, starting insoils with lower water holding capacity.

3 Adding an organic mulch like empty fruitbunches before the onset of the dry season andestablishing a leguminous cover crop.

4 Maintaining a balanced nutrition: avoiding theuse of high levels of nitrogen, particularly to-ward the end of the rainy season and keeping rec-ommended levels of potassium both in the soiland on the leaves according to plant age.

5 Keeping the soil well aerated by reducing com-paction and maintaining a proper drainage sys-tem to lower the water table and eliminatingstanding surface water. These measures can becomplemented by using varieties with toleranceto stress, particularly water deficit.

Literature

Aderungboye F. O. 1982. Significance of vascularwilt in oil palm plantations in Nigeria. The OilPalm in the eighties. The incorporated Societyof Planters, Kuala Lumpur. Pp. 475 484.

Chase A.R., Broschat T.K. 1991. (eds.) Diseasesand Disorders of Ornamental Palms, Minne-sota, APS Press. 56pp.

Chinchilla C. 1986. Evaluación de cruces toleran-tes a marchitez por Fusarium en la fase devivero en Para (Brasil). ASD de Costa Rica. In-forme interno. 23 pp.

Flood J., Copper R.M., LEESP.E. 1989. An inves-tigation of pathogenicity of four isolates of Fu-sarium oxysporum from South America, Africaand Malaysia to clonal oil palms. J. Phytopa-thology, 124(1-4): 80-88.

Flood J., Mepsted R., Cooper R.M. 1990. Contami-nation of oil palm pollen and seeds by Fusariumspp. Mycol. Res. 94(5): 708-709.

Franqueville H. 1984. Vascular wilt of the oilpalm: relationship between nursery and fieldresistance. Oleaginéux. 39(1): 516 518.

Franqueville H. and Renard J. L. 1990. Improve-ment of oil palm vascular wilt tolerance. Re-

sults and development of the disease at the R.Michaux plantation. Oleaginéux. 45(10): 399-405.

Franqueville H., Diabaté S. 2004. Status on oilpalm vascular wilt. MPOB, Inter. Conf. onPests and Diseases of Importance to the OilPalm Industry. Kuala Lumpur. 7 p. (unedited).

Ho Y.W., Varghese G., Taylor G.S. 1985. Patho-genicity of Fusarium oxysporum isolates fromMalaysia and F. oxysporum f. sp. elaeidis fromAfrica to seedlings of oil palms. Phytopatolo-gische Zeitschnift, 114(3): 193-202.

Ho Y.W., Varghese G. 1986. Pathogenic potentialof soil Fusarium from Malaysia oil palm habi-tats. J. Phytopathol. 115(4): 325-331.

Ho Y.W., Varghese G. 1987. Comparative studieson pathogenic Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.elaeidis isolates from Africa and non-pathogenic F. oxysporum from Malaysia. J.Plant Protection in the Tropics, 4(2): 129-134.

Kovachich W.G. 1948. A preliminary anatomicalnote on vascular wilt disease of the oil palm(E. guinnensis). Ann. Bot.12: 327.

ASD Oil Palm Papers, N° 36, 2011

37

-

Ollagnier R, Renard J.L. 1976. The influence ofpotassium on the resistance of oil palms to Fu-sarium oxysporum. Oleaginéux. 31 (5): 203 209.

Oritsejafor J. 1996. Weed hosts of F. oxysporum f.sp. elaeidis. Oleagineux. 4 (1): 1 7.

Prendergast A. G. 1957. Observations on the epi-demiology of vascular wilt disease of the oilpalm. J. W. Afr. Inst. Res. Oil Palm. 2, 147-175.

Prendergast A.G. 1963. A method of testing oilpalm progenies at the nursery stage for resis-tance to vascular wilt disease caused by Fusar-ium oxysporum. J. West Afr. Inst. Oil Palm Res.4 (14): 156 175.

Renard J.L., Gascon J.P., Bachy A. 1972. Researchon vascular wilt disease of the oil palm. Oleagi-néux. 27 (12): 582 590.

Renard J.L. 1979. Vascular wilt disease (F. oxyspo-rum) in the oil palm; diagnostic on the planta-tion and control methods. Oleaginéux. 34 (2):59 63.

Renard J.L., Noriet J.M., Meunier J. 1980. Sourcesand ranges of resistance to Fusarium wilt in theoil palm (E. guineensis) and E. melanococca. Ole-aginéux. 35 (8 9): 387 393.

Renard J.L., Quillec G. 1983. Fusarium and replant-ing. Elements to be considered when replant-ing oil palm in a Fusarium zone in West Africa.Oleaginéux. 38 (7): 421 427.

Renard J.L., Franqueville H. 1989. Oil palm vascu-lar wilt. Oleaginéux. 44(7):341-349.

Renard J.L., Franqueville H. 1991. Effectivenessof crop techniques in the integrated control ofoil palm vascular wilt. Oleaginéux. 46(7):255-265.

Robertson J.S., Prendergast A.G., Sly J.M.A. 1968.Diseases and disorders of the oil palm in WestAfrica. J. West Inst. Oil Palm Res. 4 (16): 381409.

Triqueb B. 1971. Pectinases et acide fusarique duF. oxysporum f. sp. elaeidis leurs rôles dans la fu-sariose du palmier á huile. Oleaginéux. 26 (3):163 168.

Turner P.D. 1981. Oil Palm Diseases and Disor-ders. The Inc. Soc. of Planter. Kuala Lumpur280 p.

Wardlaw C.W. 1946. Fusarium oxysporum on the oilpalm. Nature. 158: 712.

Wardlaw C.W. 1950. Vascular wilt disease of theoil palm caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Schl.Tropical Agric. Trin. 27: 42 47.

38

-

ASD Oil Palm Papers, N° 36, 2011

39

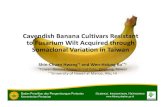

Fig. 2. Nursery palms showing symptoms ofFusarium wilt. Note short leaves andthickened and discolored bulb

Síntomas en palmitas de vivero de lainfección por Fusarium oxysporum f.sp.elaeidis, Note las hojas pequeñas yarrepolladas de las plantas a la izquierda

Fig. 3. Discolored fibers in the stem of a Fusariumwilt infected palm

Fibras descoloridas en el tronco de unapalma con la marchitez por Fusarium

Fig. 1. Fusarium wilt in adult oil palms (Marchitez por Fusarium en palmas adultas)